Wild West shows

| Part of a series on |

| Westerns |

|---|

|

Wild West shows were traveling vaudeville performances in the United States and Europe that existed around 1870–1920. The shows began as theatrical stage productions and evolved into open-air shows that depicted romanticized stereotypes of cowboys, Plains Indians, army scouts, outlaws, and wild animals that existed in the American West. While some of the storylines and characters were based on historical events, others were fictional or sensationalized.[1]

American Indians in particular were portrayed in a sensationalistic and exploitative manner.[1] The shows introduced many western performers and personalities, and romanticized the American frontier, to a wide audience.

History

[edit]

In the 19th century, following the American Civil War, stories and inexpensive dime novels depicting the American West and frontier life were becoming common. In 1869, author Ned Buntline wrote a novel about the buffalo hunter, U.S. Army scout, and guide William F. Buffalo Bill Cody called Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men after the two met on a train from California to Nebraska. In December 1872, Buntline's novel turned into a theatrical production when The Scouts of the Prairie debuted in Chicago. The show featured Buntline, Cody, Texas Jack Omohundro, and the Italian-born ballerina Giuseppina Morlacchi and toured the American theater circuit for two years.[2]

Buntline left the show and in 1874 Cody founded the Buffalo Bill Combination, in which he performed for part of the year while scouting on the prairies the rest of the year.[3] Wild Bill Hickok joined the group to headline in a new play called Scouts of the Plains. Hickok did not enjoy acting and was released from the group after one show when he shot out a spotlight that focused on him.[4]

Texas Jack parted ways with Cody in 1877 and formed his own acting troupe in St. Louis, known as the 'Texas Jack Combination', and in May of that year he debuted Texas Jack in the Black Hills.[5] Other plays the combination performed included The Trapper's Daughter and Life on the Border.

In 1883, Cody founded Buffalo Bill's Wild West, an outdoor attraction that toured annually.[6] The new show contained a lot of action including wild animals, trick performances, and theatrical reenactments. All sorts of characters from the frontier were incorporated into the show's program. Shooting exhibitions were also in the lineup with extensive shooting displays and trick shots. Rodeo events, involving rough and dangerous activities performed by cowboys with different animals, also featured. It was the first and prototypical Wild West show, lasting until 1915, and featured theatrical reenactments of battle scenes, characteristic western scenes, and even hunts.[7]

Buffalo Bill's Wild West

[edit]

In 1883, Buffalo Bill's Wild West was founded in Omaha, Nebraska when Buffalo Bill Cody turned his real life adventure into the first outdoor western show.[8] The show's publicist Arizona John Burke employed innovative techniques at the time, such as celebrity endorsements, press kits, publicity stunts, op-ed articles, billboards and product licensing, that contributed to the success and popularity of the show.[9]

Buffalo Bill's Wild West toured Europe eight times, the first four tours between 1887 and 1892, and the last four from 1902 to 1906.[10] The first tour was in 1887 as part of the American Exhibition, which coincided with the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria.[11] The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, requested a private preview of the Wild West performance; he was impressed enough to arrange a command performance for Queen Victoria. The Queen enjoyed the show and meeting the performers, setting the stage for another command performance on June 20, 1887, for her Jubilee guests. Royalty from all over Europe attended, including the future Kaiser Wilhelm II and the future King George V.[12] Buffalo Bill's Wild West closed its successful London run in October 1887 after more than 300 performances, with more than 2.5 million tickets sold.[13] The tour made stops in Birmingham and Manchester before returning to the United States in May 1888 for a short summer tour. A return tour was made in 1891-92,[14] including Cardiff, Wales and Glasgow, Scotland, in the itinerary.

In 1893, Cody changed the title to Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World and the show performed at the Chicago World's Fair to a crowd of 18,000. This performance was a huge contributor to the show's popularity. The show never again did as well as it did that year. That same year at the Fair, Frederick Turner, a young Wisconsin scholar, gave a speech that pronounced the first stage of American history over. "The frontier has gone", he declared.[15]

Buffalo Bill's Wild West returned to Europe in December 1902 with a fourteen-week run in London, capped by a visit from King Edward VII and the future King George V. The Wild West traveled throughout Great Britain in a tour in 1902 and 1903 and a tour in 1904, performing in nearly every city large enough to support it.[16] The 1905 tour began in April with a two-month run in Paris, after which the show traveled around France, performing mostly one-night stands, concluding in December. The final tour, in 1906, began in France on March 4 and quickly moved to Italy for two months. The show then traveled east, performing in Austria, the Balkans, Hungary, Romania, and Ukraine, before returning west to tour in Poland, Bohemia (later Czech Republic), Germany, and Belgium.[17]

By 1894 the harsh economy made it hard to afford tickets. It did not help that the show was routed to go through the South in a year when the cotton was flooded and there was a general depression in the area. Buffalo Bill lost a lot of money and was on the brink of a financial disaster. Soon after, and in an attempt of recovery of monetary balance, Buffalo Bill signed a contract in which he was tricked by Bonfil and Temmen into selling them the show and demoting himself to a mere employee and attraction of the Sells-Floto Circus. From this point, the show began to destroy itself. Finally, in 1913 the show was declared bankrupt.[18]

Show content

[edit]

The shows consisted of reenactments of history combined with displays of showmanship, sharpshooting, hunts, racing, or rodeo style events. Each show was 3–4 hours long and attracted crowds of thousands of people daily. The show began with a parade on horseback. The parade was a major ordeal, an affair that involved huge public crowds and many performers, including the Congress of Rough Riders.

Events included acts known as Bison Hunt, Train Robbery, Indian War Battle Reenactment, and the usual grand finale of the show, Attack on the Burning Cabin, in which Indians attacked a settler's cabin and were repulsed by Buffalo Bill, cowboys, and Mexicans. Also included were semi-historical scenes such as a settler perspective of the Battle of the Little Bighorn or the charge on San Juan Hill. The reenactment of the Battle of Little Bighorn also known as "Custer's Last Stand" featured Buck Taylor starring as General George Armstrong Custer. In this battle, Custer and all men under his direct command were killed. After Custer is dead, Buffalo Bill rides in, the hero, but he is too late. He avenges Custer by killing and scalping Yellow Hair (also called Yellowhand) which he called the "first scalp for Custer".[19]

Shooting competitions and displays of marksmanship were commonly a part of the program. Great feats of skill were shown off using rifles, shotguns, and revolvers. Most people in the show were good marksmen but many were experts.

Animals also did their share in the show through rodeo entertainment. In rodeo events, cowboys like Lee Martin would try to rope and ride broncos. Broncos are unbroken horses that tend to throw or buck their riders. Other wild animals they would attempt to ride or deal with were mules, buffalo, Texas steers, elk, deer, bears, and moose. The show also demonstrated hunts which were staged as they would have been on the frontier, and were accompanied by one of the few remaining buffalo herds in the world.[20]

Races were another form of entertainment employed in the Wild West show. Many different races were held, including those between cowboys, Mexicans, and Indians,[citation needed] a 100 yd foot race between Indian and Indian pony,[citation needed] a race between Sioux boys on bareback Indian ponies,[citation needed] races between Mexican thoroughbreds, and even a race between Lady Riders.

Other shows

[edit]

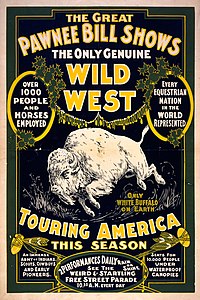

Over time, various Wild West shows were developed. They included Bee Ho Gray's Wild West, Texas Jack's Wild West, Pawnee Bill's Wild West, Jones Bros.' Buffalo Ranch Wild West, Cummin's Indian Congress and Wild West Show[21] and "Buckskin Joe" Hoyt.[22]

The 101 Ranch Wild West Show featuring African Americans such as Bill Pickett, the famous bulldogger and his brother Voter Hall who billed as a "Feejee Indian from Africa".[23]

The Esquivel Brothers from San Antonio.[23]

Performers

[edit]

Wild West shows contained as many as 1,200 performers at one time (cowboys, scouts, Indians, military, Mexicans, and men from other heritages) and many animals, including buffalo and Texas Longhorns. Some of the recognizably famous men who took part in the show were Will Rogers, Tom Mix, Pawnee Bill, James Lawson, Bill Pickett, Jess Willard, Mexican Joe, Capt. Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Harry Henry Brennan (father of modern bronc riding),[24] Grover C. Brennan, Ralph and Nan Lohse, Antonio Esquibel, Capt. Waterman and his Trained Buffalo, and Johnny Baker. Johnny Baker was nicknamed the "Cowboy Kid" and considered to be Annie Oakley's boy counterpart. Some notable cowboys who participated in the events were Buck Taylor (dubbed "The First Cowboy King"), Bronco Bill, James Lawson ("The Roper"), Bill Bullock, Tim Clayton, Coyote Bill, sharpshooter James Spleen ("Kit Carson Jr"), frontiersman John Baker Omohundro ("Texas Jack"), and Bridle Bill.

Women were also a large part of Wild West shows and attracted many spectators. One such performer was Annie Oakley, who first gained recognition as a sharpshooter when she defeated Frank Butler, a pro marksman at age 15, in a shooting exhibition. She became an attraction of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show for 16 years. Annie was billed in the show as "Miss Annie Oakley, the Peerless Lady Wing-Shot".[25]

Calamity Jane was another distinguished woman performer. Calamity Jane was a notorious frontierswoman who was the subject of many wild stories—many of which she made up herself. She was a skilled horsewoman and expert rifle and revolver handler in the show. Calamity Jane appeared in Wild West shows until 1902 when she was reportedly fired for drinking and fighting.[26]

Other notable females in the business were Tillie Baldwin, May Lillie, Lucille Mulhall, Lillian Smith, Bessie and Della Ferrel, Luella-Forepaugh Fish,[27] the Kemp Sisters, and Texas Rose as an announcer.[28]

"Show Indians" - actors largely from the Plains Nations, such as the Lakota people - were also a part of Wild West shows.[1] They were hired to participate in staged "Indian Races" and what were alleged to be historic battles, and often appeared in attack scenes attacking whites in which they were encouraged to portray "savagery and wildness".[1] The shows "generally presented Native people as exotic savages, prone to bizarre rites and cruel violence."[1] The Native women were dressed in "exploitative", non-traditional clothing such as men's headdresses and breastplates, combined with immodest attire like leather shorts, none of which would have ever been worn in reality.[1] They also performed what was billed as "the Sioux Ghost Dance".[29]

Chief Sitting Bull joined Cody's Wild West show for a short time and was a star attraction alongside Annie Oakley. During his time at the show, Sitting Bull was introduced to President Grover Cleveland, which he thought proved his importance as chief. He was friends with Buffalo Bill and highly valued the horse that was given to him when he left the show. [30]

Red Eagle (1870–1949) immersed himself in a three-year training period at Cody's base in North Platte, Nebraska. During this time, he honed his skills in steer roping, lariat tricks, and the art of maintaining a firm grip on "anything that had four legs." His debut in the spotlight occurred at the age of thirteen, portraying a Pony Express rider. Merely a year later, the Show set off on a tour across Europe. Over the span of several years, Red Eagle became an integral member of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, captivating audiences throughout his journey.[31][32][33]

Other familiar Native Americans names who performed in the show were Red Cloud,[34] Chief Joseph,[35] Geronimo[citation needed], and the Modoc War scout Donald McKay.

Influence and legacy

[edit]Western shows generated interest for Western entertainment. This is still evidenced in western films, modern rodeos, and circuses.[20] Western films in the first half of the 20th century filled the gap left behind by Wild West shows.[citation needed] The first real western, The Great Train Robbery, was made in 1903, and thousands followed after. In the 1960s Spaghetti Westerns, a genre of movies about the American Old West made in Europe, were common.

Contemporary rodeos continue to be held, employing the same events and skills as cowboys did in Wild West shows. Wild Westers still perform in movies, pow-wows, pageants and rodeos. There remains an interest in Native peoples through much of the United States and Europe, including an interest in the pow-wow culture of Native people. Some events are open to outside tourists who are able to observe traditional Native American skills: horse culture, ceremonial dancing, food, art, music and crafts, while other pow-wows are closed events for members of the Native community only.

There are several ongoing national projects that celebrate Wild Westers and Wild Westing. The National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution preserves and displays Gertrude Käsebier's photographs, as well as many others by photographers who captured the displays of Wild Westing.

The Carlisle Indian School Resource Center of the Cumberland County Historical Society in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, houses an extensive collection of archival materials and photographs from the Carlisle Indian School. In 2000, the Cumberland County 250th Anniversary Committee worked with Native Americans from numerous tribes and non-natives to organize a pow-wow on Memorial Day to commemorate the Carlisle Indian School, the students and their stories.[36]

See also

[edit]- Buffalo Girls (1995 film), depicts Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

- Circus

- Georgian horsemen in Wild West shows

- Hippodrama

- Rodeo

- Sideshow

- Trick roping

- Variety show

- Vaudeville

- Wild Westing

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Stanley, David (November 12, 2014). "JFR Review for Native Performers in Wild West Shows: From Buffalo Bill to Euro Disney". Journal of Folklore Research. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ^ Gallop (2001), pp. 24; 29–31.

- ^ Johnson, Geoffrey. "Flashback: 'Buffalo Bill' Cody wowed Chicago with his 'Wild West' shows". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Burns, Walter Noble (November 2, 1911). "Frontier Hero - Reminiscences of Wild Bill Hickok by his old Friend Buffalo Bill". The Blackfoot Optimist. (Blackfoot, Idaho). Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "Wood's Theater". The Cincinnati Daily Star. May 15, 1877. Archived from the original on 2021-11-21. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "William "Buffalo Bill" Cody". World Digital Library. 1917. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ Utley (2003), p. 254.

- ^ Pendergast (2000), p. 49.

- ^ Gazette Staff (Apr 12, 2017). "Grave of Buffalo Bill's promoter will finally get headstone". Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Griffin (1908), p. xviii.

- ^ "William F. Cody Archive: Documenting the Life and Times of Buffalo Bill".

- ^ Russell (1960), pp. 330–331.

- ^ Gallop (2001), p. 129.

- ^ 1891-92—Dates and venues Archived 2021-07-09 at the Wayback Machine at www.snbba.co.uk

- ^ Sonneborn (2002), p. 137.

- ^ Russell (1960), p. 439.

- ^ Moses (1996), p. 189.

- ^ Sonneborn (2002), p. 117.

- ^ Sorg (1998), p. 26.

- ^ a b Swanson (2004), p. 42.

- ^ "Category:Colonel Cummin's Indian Congress and Wild West Show - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org. Archived from the original on 2023-10-22. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Buckskin Joe". Arkansas City Republican. 1878–1888. Archived from the original on 2015-08-08. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ a b Fees, Paul - Former Curator. "Wild West shows: Buffalo Bill's Wild West". Buffalo Bill Museum. Archived from the original on 2017-07-16. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- ^ "National Cowboy Museum". Archived from the original on 2022-12-01. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ "Biography: Annie Oakley". WGBH American Experience. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Griske (2005), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Dinkins (2009), p. 71.

- ^ George-Warren (2010), p. 33.

- ^ Kasson (2000), p.162.

- ^ Stillman (2017), pp. 173–174; 182–183.

- ^ Richard Flower (2014). "Red Eagle: The Wild West Comes To Carmel". Stories of Old Carmel: A Centennial Tribute From The Carmel Residents Association (PDF). Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Carmel Residents Association. pp. 163–164. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-17. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ Irene Alexander (September 10, 1943). "Red Eagle Performed for Victoria, Knew Bad Men of the Early West". Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Carmel Pine Cone. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ M. Omoran (1948). Red Eagle: Buffalo Bill's Adopted Son. New York: J. B. Lippincott Company. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ "Indian Warriors in the Battle of the Little Bighorn & Wild West Shows" (PDF). Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. April 26, 2014. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Evening star. Washington, D.C.: W. D. Wallach & Hope. 1897. OCLC 02260929. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ^ Witmer, Linda F. "Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1879 - 1918)". Cumberland County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2013-05-29.

Bibliography

- Dinkins, Greg (2009). Minnesota in 3D: A Look Back in Time: With Built-in Stereoscope Viewer-Your Glasses to the Past!. Voyageur Press. ISBN 9781616731748.

- Gallop, Alan (2001). Buffalo Bill's British Wild West. Sutton. ISBN 9780750927024.

- George-Warren, Holly (2010). The Cowgirl Way: Hats Off to America's Women of the West. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 33. ISBN 9780547488059.

- Griffin, Charles Eldridge (1908). Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803234666.

- Griske, Michael (2005). The Diaries of John Hunton: Made to Last, Written to Last : Sagas of the Western Frontier. Heritage Books. ISBN 0-7884-3804-2.

- Kasson, Joy S. (2000). Buffalo Bill's Wild West. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809032433.

- Moses, L. G. (1996). Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826316851.

- Pendergast, Tom (2000). Westward Expansion: Almanac. UXL. ISBN 9780787648626.

- Russell, Don (1960). The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806115375.

- Sonneborn, Liz (2002). The American West: An Illustrated History. Scholastic Incorporated. ISBN 9780439219709.

- Sorg, Eric V. (1998). Buffalo Bill: Myth & Reality. Ancient City Press. ISBN 9781580960038.

- Stillman, Deanne (2017). Blood Brothers: The Story of the Strange Friendship Between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781476773520.

- Swanson, Wayne (2004). Why the West Was Wild. Annick Press. ISBN 9781550378375.

- Utley, Robert M. (2003). The Story of the West. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 254. ISBN 9780789496607.