Cape Malays

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

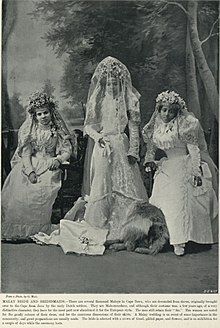

Cape Malay brides and bridesmaids in South Africa | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 325,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| South Africa Western Cape, Gauteng | |

| Languages | |

| Afrikaans, South African English Historically Malay, Makassarese, Dutch, Arabic Afrikaans[2][3] | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Javanese, Malays, Indians, Malagasy, Cape Dutch, Dutch, Cape Coloureds, Bugis, Makassar, Madura |

Cape Malays (Afrikaans: Kaapse Maleiers, کاپز ملیس in Arabic script) also known as Cape Muslims or Malays, are a Muslim community or ethnic group in South Africa. They are the descendants of enslaved and free Muslims from different parts of the world, specifically Indonesia (at that time known as the Dutch East Indies) and other Asian countries, who lived at the Cape during Dutch and British rule.

Although early members of the community were from the Dutch colonies of Southeast Asia, by the 1800s, the term "Malay" encompassed all practising Muslims at the Cape regardless of origin. Since they used Malay as a lingua franca and language of religious instruction, the community began to be referred to as Malays.

Malays are concentrated in the Cape Town area. The community played an important role in the history of Islam in South Africa, and its culinary culture is an integral part of South African cuisine. Malays helped to develop Afrikaans as a written language, initially using an Arabic script.

"Malay" was legally a subcategory of the Coloured racial group during the apartheid era.

History

[edit]The Dutch East India Company established a colony at the Cape of Good Hope (the Dutch Cape Colony) as a resupply station for ships travelling between Europe and Asia, which developed into the city of Cape Town. The Dutch had also colonised the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia),[4] which formed a part of the Dutch Empire for several centuries, and Dutch Malacca,[5] which they held from 1641 until 1824.[6]

Islamic figures such as Sheikh Yusuf, a Makassarese noble and scholar from Sulawesi, who resisted the company's rule in Southeast Asia, were exiled to South Africa. They were followed by slaves from other parts of Asia and Africa. Although it is not possible to accurately reconstruct the origins of slaves in the Cape, it has been estimated that roughly equal proportions of Malagasies, Indians, Insulindians (Southeast Asians), and continental Africans were imported, with other estimates showing that the majority of slaves originated in Madagascar.[7]

Many "Indiaanen" and "Mohammedaanen" Muslim political prisoners brought from Southeast Asia were imprisoned on Robben Island. Among these were Tuan Guru, first chief imam in South Africa. Sheikh Madura was exiled in the 1740s and died on Robben Island; his kramat (shrine) is still there today.[8]

Although the majority of slaves from Southeast Asia were already Muslims, along with many Indians, those from Madagascar and elsewhere in Africa were not. The slaves from Asia tended to work in semi-skilled and domestic roles, and they made up a disproportionate share of 18th-century manumissions, who subsequently settled in Bo-Kaap, while those from elsewhere in Africa and Madagascar tended to work as farmhands and were not freed at the same rate.[7] In the latter part of the 18th century, conversions to Islam of rural non-Asian slaves increased due to a Dutch colonial law that encouraged owners to educate their slaves in Christianity, and following their baptism, to allow them to buy their freedom. This consequently resulted in slave owners, fearful of losing their slaves, not enforcing Christianity amongst them. This, in turn, allowed Islamic proselytisers to convert the slaves.[7]

There were also skilled Muslim labourers called Mardijkers from Southeast Asia who settled in the Bo-Kaap area of Cape Town.[9]

After the British took the Cape and began phasing out slavery in the first half of the 19th century, the newly freed non-Asian Muslim rural slaves moved to Cape Town, the only centre of Islamic faith in the region. The South and Southeast Asians constituted the Muslim establishment in the colony, and the newly freed slaves subsequently adopted the Malay language used by the Asians.[7] Thus, Malay was the initial lingua franca of Muslims, though they came from East Africa, Madagascar, and India as well as Indonesia, and established the moniker "Malay" for all Muslims at the Cape, irrespective of their geographic origins.[10] By the 19th century, the term was used to describe anyone at the Cape who was a practising Muslim,[11] despite Afrikaans having overtaken Malay as the group's lingua franca.

The community adopted Afrikaans as a lingua franca to ease communication between Asian and non-Asian Muslims (who had adopted the Dutch used by their masters), and because the utility of Malay and the Malayo-Portuguese language were diminished due to the British ban on slave imports in 1808, reducing the need to communicate with newcomers. Asian and non-Asian Muslims interacted socially despite the initial linguistic differences and gradually blended into a single community.[7] In 1836, the British colonial authorities estimated that the Cape Malay population at the time was around 5,000 out of a total population for the Cape of 130,486.[12]

"Malay" was legally a subcategory of the Coloured race group during Apartheid,[13][14] though the delineation of Malays and the remaining defined Coloured subgroups by government officials was often imprecise and subjective.[15]

Cultural identity

[edit]

The Cape Malays (Afrikaans: Kaapse Maleiers, کاپز ملیس in Arabies script) also known as Cape Muslims[16] or simply Malays, are a Muslim community or ethnic group in South Africa.[11]

The Cape Malay identity can be considered the product of a set of histories and communities as much as it is a definition of an ethnic group. Since many Cape Malay people have found their Muslim identity to be more salient than their "Malay" ancestry, in some contexts, they have been described as "Cape Malay", or "Malays", and others as "Cape Muslim" by people both inside and outside of the community.[16] Cape Malay ancestry includes people from South[10] and Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and Khoekhoe descent. Later, Muslim male "Passenger Indian" migrants to the Cape married into the Cape Malay community, with their children being classified as Cape Malay.[17]

Muslim men in the Cape started wearing the Turkish fez after the arrival of Abu Bakr Effendi, an imam sent from the Ottoman Empire[18] at the request of the British Empire[19] to teach Islam in the Cape Colony. At a time when most imams in the Cape were teaching the Shafi`i school of Islamic jurisprudence, Effendi was the first teacher of the Hanafi school and established madrassas (Islamic schools) in Cape Town. Effendi, in common with many Turkish Muslims, wore a distinctive red fez.[18][20] Many Cape Malay men continue to wear the red fez[21] (in particular the Malay choirs[22]), although black was also common, and more recently, other colours have become popular. The last fez-maker in Cape Town closed shop in March 2022; 76-year-old Gosain Samsodien had been making fezzes in his home factory in Kensington for 25 years.[23]

Demographics

[edit]It is estimated that there are[when?] about 166,000 people in Cape Town who could be described as Cape Malay, and about 10,000 in Johannesburg. The Malay Quarter of Cape Town is found on Signal Hill and is called the Bo-Kaap.[citation needed]

Many Cape Malay people also lived in District Six before they, among other South African people of diverse ethnicity, mainly Cape Coloureds, were forcefully removed from their homes by the apartheid government and redistributed into townships on the Cape Flats.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]The founders of the Cape Malay community were the first to bring Islam to South Africa. The community's culture and traditions have also left an impact that is felt to this day. The Muslim community in Cape Town remains large and has expanded significantly since its inception.[24][25]

Language

[edit]A dialect of Malay emerged among the enslaved community and later spread among colonial European residents of Cape Town between the 1780s and the 1930s. A unique dialect formed during this period from a substrate of Betawi spoken in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), from which all major Dutch East India Company shipments took place, combined with Tamil, Hindustani, and Arabic influences. A significant number of this vocabulary has survived in the Afrikaans sociolect spoken by subsequent generations.[26]

| Original Malay | Cape equivalent, with attested Dutch ortography | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| berguru | <banghoeroe> | to study with someone |

| pergi | <piki> | to go |

| gunung | <goeni> | mountain |

| cambuk | <sambok> | horsewhip |

| jamban | <djammang> | toilet |

| ikan tongkol | <katonkel> | skipjack tuna |

| puasa | <kewassa> | to fast |

| kemparan | <kaparrang> | farm or work boots |

| tempat ludah | <tamploera> | spittoon |

| ubur-ubur | <oeroer> | jellyfish |

| penawar | <panaar> | antidote |

| minta maaf | <tamaaf> | sorry |

Cuisine

[edit]

Adaptations of traditional foods such as bredie, bobotie, sosaties, and koeksisters are staples in many South African homes. Faldela Williams wrote three cookbooks, including The Cape Malay Cookbook, which became instrumental in preserving the cultural traditions of Cape Malay cuisine.[27][28]

Music

[edit]

The Cape Malay community developed a characteristic musical style. This includes a secular folk song type of Dutch origin, known as the nederlandslied. The language and musical style of this genre reflects the history of South African slavery, and the words and music often reflect sadness and other emotions related to the effect of enslavement. The nederlandslied shows the influence of the Arabesque style of singing and is unique in South Africa.[29]

The Silver Fez is the "Holy Grail" of the musical subculture. The contest involves thousands of musicians and a wide variety of tunes,[30][31] with all-male choirs from the Malay community competing for the prize. A 2009 documentary film directed by Lloyd Ross (founder of Shifty Records,[31]) called The Silver Fez, focuses on an underdog competing for the award.[29]

The annual Cape Town Minstrel Carnival (formerly known as the Coon Carnival) is a deep-rooted Cape Malay cultural event; it incorporates the comic song, or moppie (often also referred to as ghoema songs), as well as the nederlandslied.[32] A barrel-shaped drum, called the ghoema (also spelled ghomma, or known as dhol), is also closely associated with Cape Malay music, along with other percussion instruments such as the rebanna (rebana) and tamarien (tambourine). Stringed instruments include the ra'king, gom-gom, and besem (also known as skiffelbas).[33] The ghomma has been traditionally used mostly for marching or rhythmic songs known as the ghommaliedjie, while the guitar is used for lyrical songs.[34]

International relationships

[edit]Connections between Malaysians and South Africans improved when South Africa rejoined the international community. This was welcomed by the Malaysian government and many others in the Southeast Asian region. Non-governmental organisations, such as the Federation of Malaysia Writers' Associations, have since set on linking up with the diasporic Cape Malay community.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ "Malay, Cape in South Africa". Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Stell, Gerald (2007). "From Kitaab-Hollandsch to Kitaab-Afrikaans: The evolution of a non-white literary variety at the Cape (1856-1940)". Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics (PDF). 37. Stellenbosch University. doi:10.5774/37-0-16.

- ^ "The Indonesian anti-colonial roots of Islam in South Africa". 25 August 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Vahed, Goolam (13 April 2016). "The Cape Malay:The Quest for 'Malay' Identity in Apartheid South Africa". South African History Online. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Winstedt, Sir Richard Olof (1951). "Ch. VI: The Dutch at Malacca". Malaya and Its History. London: Hutchinson University Library. p. 47.

- ^ Wan Hashim Wan Teh (24 November 2009). "Melayu Minoriti dan Diaspora; Penghijrahan dan Jati Diri" [Malay Minorities and Diaspora; Migration and Self Identity] (in Malay). Malay Civilization Seminar 1. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Stell, Gerald; Luffin, Xavier; Rakiep, Muttaqin (2008). "Religious and secular Cape Malay Afrikaans: Literary varieties used by Shaykh Hanif Edwards (1906-1958)". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia. 163 (2–3): 289–325. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003687. ISSN 0006-2294.

- ^ "Kramat". Robben Island Museum. 27 July 2003. Archived from the original on 9 September 2005. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Davis, Rebecca. "Bo-Kaap's complicated history and its many myths". ewn.co.za.

- ^ a b "Indian slaves in South Africa". Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ^ a b Pettman, Charles (1913). Africanderisms; a glossary of South African colloquial words and phrases and of place and other names. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 51.

- ^ Martin, Robert Montgomery (1836). The British Colonial Library: In 12 volumes. Mortimer. p. 125.

- ^ "Race Classification Board: An appalling 'science'". Heritage.thetimes.co.za. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Leach, Graham (1987). South Africa: no easy path to peace. Methuen paperback. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-413-15330-2.

- ^ Vashna Jagarnath, June 2005The Population Registration Act and Popular Understandings of Race: A case study of Sydenham, p.9.

- ^ a b "Cape Malay | South African History Online". V1.sahistory.org.za. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ "The Beginnings of Protest, 1860–1923 | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b Worden, N.; Van Heyningen, E.; Bickford-Smith, V. (2004). Cape Town: The Making of a City: an Illustrated Social History. David Philip. ISBN 978-0-86486-656-1. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Ottoman descendants in South Africa get Turkish citizenship". Daily Sabah. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Argun, Selim (2000). "Life and Contribution of Osmanli Scholar, Abu bakr Effendi, towards Islamic thought and Culture in South Africa" (PDF). pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Man demonstrates how a fez is made, Cape Town". UCT Libraries Digital Collections. University of Cape Town. 22 July 1970. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Landsberg, Ian (17 March 2022). "Watch: The Cape's last fez maker closes shop". The Daily Voice. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Landsberg, Ian (14 March 2022). "Last of his kind: Traditional fez maker in Kensington hangs up his hat". IOL. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Mahida, Ebrahim Mahomed (13 January 2012). "1699 by Ebrahim Mahomed Mahida – South African History Online". History of Muslims in South Africa: 1652. Retrieved 19 February 2023 – via South African History Online.

- ^ "History of Muslims in South Africa". Maraisburg. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Hoogervorst, Tom (2021). ""Kanala, tamaaf, tramkassie, en stuur krieslam"; Lexical and phonological echoes of Malay in Cape Town". Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia. 22 (1): 22–57. doi:10.17510/wacana.v22i1.953.

- ^ "Bo-Kaap: o bairro colorido de Cape Town". Viin (in Portuguese). 15 September 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ^ Lewis, Esther (27 May 2014). "Faldela Williams lives on in cookbook". Johannesburg, South Africa: IOL. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b De Waal, Shaun (16 September 2009). "The Song remains the same". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "The Silver Fez" (text and video). Al Jazeera. Witness. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b 7ª Edición (PDF) (in French, Spanish, and English). Festival de Cine Africano de Tarifa / Tarifa African Film Festival (FCAT). May 2010. pp. 86–87.

Available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. (See talk page)

Available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. (See talk page)

- ^ Desai, Desmond (24 February 2007). "Home". DMD EDU. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Desai, Desmond (11 August 2006). "Some unique Cape musical instruments". DMD EDU. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Kirby, Percival R. (December 1939). "Musical instruments of the Cape Malays". South African Journal of Science. XXXVI: 477–488.

- ^ Haron, Muhammed (2005). "Gapena and the Cape Malays: Initiating Connections, Constructing Images" (PDF). SARI: Jurnal Alam Dan Tamadun Melayu. 23. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: 47–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Official South African history site – early context for Cape Malay community

- Haron, Muhammed (2001). "Conflict of Identities: The Case of South Africa's Cape Malays"

- Information about Cape Malay musical instruments and music

- Cape Mazaar Society (formerly the Robben Island Mazaar (Kramat) Committee)