Darkness on the Edge of Town

| Darkness on the Edge of Town | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | June 2, 1978 | |||

| Recorded | June 1977 – March 1978 | |||

| Studio | Atlantic and Record Plant (New York City) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:29 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Bruce Springsteen chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Darkness on the Edge of Town | ||||

| ||||

Darkness on the Edge of Town is the fourth studio album by the American singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen, released on June 2, 1978, by Columbia Records. The album was recorded after a series of legal disputes between Springsteen and his former manager Mike Appel, during sessions in New York City with the E Street Band from June 1977 to March 1978. Springsteen and Jon Landau served as producers, with assistance from bandmate Steven Van Zandt.

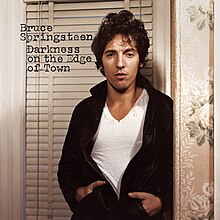

For the album's lyrics and music, Springsteen took inspiration from sources as diverse as John Steinbeck novels, John Ford films, punk rock, and country music. Musically, the album strips the Wall of Sound production of its predecessor, Born to Run (1975) for a rawer hard rock sound emphasizing the band as a whole. The lyrics on Darkness focus on ill-fortuned characters who fight back against overwhelming odds. Compared to Springsteen's previous records, the characters are older and the songs are less tied to the Jersey Shore area. The cover photograph of Springsteen was taken by Frank Stefanko in his New Jersey home.

Released three years after Born to Run, Darkness did not sell as well as its predecessor but reached number five in the US, while its singles—"Prove It All Night", "Badlands", and "The Promised Land"—performed modestly. Springsteen and the E Street Band promoted the album on the Darkness Tour, their largest tour up to that point. Upon release, critics praised the album's music and performances but were divided on the lyrical content. It placed on several critics' lists ranking the best albums of the year.

In later decades, Darkness has attracted acclaim as one of Springsteen's best works and one that anticipated later records. It has since appeared on various professional lists of the greatest albums of all time. Outtakes from the recording sessions were given to other artists, held over for Springsteen's next album, The River (1980), or later released on compilations. Darkness was reissued in 2010, accompanied by a documentary detailing the album's making.

Background

[edit]Bruce Springsteen released his third studio album, Born to Run, in August 1975, which was his breakthrough album, propelling him to worldwide fame.[1][2] Despite the album's success, Springsteen was subject to a critical backlash from some music critics and journalists when they questioned whether the album deserved its popularity or if Springsteen lived up to the media hype then surrounding him.[a][5][6][7] Following its release, Springsteen had disagreements with his manager, Mike Appel; Appel wanted to capitalize on the album's success with a live album, while Springsteen wanted to return to the studio with his Born to Run co-producer Jon Landau.[8][9][10]

Realizing that the terms of his record contract were unfavorable, Springsteen sued Appel in July 1976 for ownership of his work. The resulting legal proceedings prevented him from recording in a studio for almost a year,[b] during which he toured the United States and Europe with the E Street Band – Roy Bittan (piano), Clarence Clemons (saxophone), Danny Federici (organ), Garry Tallent (bass), Steven Van Zandt (guitar), and Max Weinberg (drums). Springsteen wrote new material on the road and at his farm home in Holmdel, New Jersey, reportedly amassing between 40 and 70 songs.[11][12] The lawsuit reached a settlement on May 28, 1977, in which Springsteen bought out his contract with Appel, who received a lump sum and a share of royalties from Springsteen's first three albums.[c][9][11][13]

Production

[edit]Recording history

[edit]

Springsteen entered Atlantic Studios in New York City with Landau and the E Street Band to record his next album on June 1, 1977,[14] four days after the legal proceedings ended.[11][13] Springsteen initially focused on pre-written material before turning his attention to unfinished compositions for which he had written music but not lyrics.[15] Songs recorded or attempted at Atlantic, some of which he had used in live sets, included: "Rendezvous", "The Promise", "Frankie", "Don't Look Back", "Something in the Night", "Because the Night", "Racing in the Street", "Fire" (which Springsteen wrote for Elvis Presley), "Breakaway", "Our Love Will Last Forever", a ballad titled "One Way Street", and two rockers named "I Wanna Be with You" and "Outside Lookin' In".[15][16][17][18] Unlike the sessions for Born to Run, the full band recorded the songs at once and moved quickly from one to the next, often shortly after Springsteen had written them.[19][20] Landau had informed CBS Records to not schedule a release date, wanting to ensure Springsteen had the right songs for the album at the right time.[d][22]

By September 1977, Springsteen grew frustrated with Atlantic's sound and environment and moved recording to the Record Plant, where most of Born to Run had been recorded.[e] Weinberg, who suffered from illness during most of the sessions,[11] remembered Springsteen demanding perfection from the musicians while simultaneously giving them little direction, saying he "[let] things flow" and did not "nitpick over details".[23] Van Zandt also had a hand in the arrangements,[24] and received a production assistance credit on the album.[19] Songs that took shape between September and November included "Don't Look Back", "Something in the Night", "Badlands", "Streets of Fire", "Prove It All Night", "Independence Day", and "The Promised Land".[f][26] The new album was to be titled Badlands, running eight tracks long like Born to Run, and a mockup album sleeve was created.[g][27] Springsteen reportedly scrapped the title to avoid confusion with a Bill Chinnock album of the same name,[28][29] originally released in 1977 and reissued in 1978.[30]

With Springsteen still unsatisfied, the sessions continued into November and December, with the band recording "Adam Raised a Cain" and "Give the Girl a Kiss".[27][31] The ballad "Let's Go Tonight" was rewritten as "Factory" with new lyrics and the incomplete compositions "Candy's Boy" and an untitled piece referred to as "The Fast Song" were combined into "Candy's Room".[27] "Darkness on the Edge of Town" was recorded during the tail end of the sessions in March 1978;[h] Springsteen later said the band found the song's drum sound in Record Plant's Studio A while it was being renovated.[33] The intention to record most of the backing tracks live with minimal overdubs was hindered by the studio's carpeted floors, which muffled resonance.[11] The sessions reportedly yielded between 50 and 70 songs, although only 32 are known.[11]

After nine months,[19] recording completed in January 1978,[i] with overdubs extending into February and March.[11] According to the authors Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon, Springsteen had a rule when choosing songs for the final track list: "Each song had to remain sober and austere, so as to convey its message as effectively as possible."[11] Choosing ten tracks for the album, now called Darkness on the Edge of Town, he scrapped songs he felt did not fit the desired theme, were too bland, or too commercial.[11] He gave several songs to other artists: "Hearts of Stone" and "Talk to Me" to Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes;[35] "Because the Night" to Patti Smith; "Fire" to Robert Gordon;[j][11][37] "Rendezvous" to Greg Kihn; "Don't Look Back" to the Knack; and "This Little Girl" to Gary U.S. Bonds.[13][36] The tracks "Independence Day", "Drive All Night", "Sherry Darling", and "Ramrod" were held over for Springsteen's next album, The River (1980), while others surfaced on bootlegs before official releases on compilations such as Tracks (1998) and The Promise (2010).[36][38][39] "Darlington County", later recorded for and released on Born in the U.S.A. (1984), was also written during the Darkness sessions.[40] Springsteen said in a 1978 interview that he felt it "wasn't the right time" to release the extra material, nor did he want to "sacrifice the intensity" of the album.[41]

Sound and mixing

[edit]Springsteen struggled to achieve the exact sounds he envisioned for the record, which he admitted was due to his and Landau's inexperience as producers. He wrote in his 2016 autobiography that "as with Born to Run, our recording process was thwarted by our seeming inability to get the most basic acceptable sounds."[42] While Landau wanted "a highly professional, technically perfect sound", Van Zandt sought a "more garage-band tone color". Springsteen assigned the engineer Jimmy Iovine to create a combination of the two's ideals; however Iovine and the assistant engineer Thom Panunzio struggled to achieve this goal. Iovine found trying to get the guitar sound was "impossible", while Panunzio described the drums as the hardest to record.[11]

Mixing extended into May 1978, specifically for "The Promised Land".[43] Iovine, suffering from exhaustion after months of recording,[k] was replaced by the Los Angeles producer and engineer Chuck Plotkin, who created a balanced mix.[l] The album was mastered by Mike Reese in Los Angeles.[11] Van Zandt hated the final mix, saying the final record contained some of Springsteen's "best and most important songs", but suffered from "terrible production".[45]

Music and lyrics

[edit]When writing the album's songs, Springsteen was particularly influenced by works of fiction that focused on individuals confronted by adversity; these included the John Steinbeck novels The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and East of Eden (1952) and their respective film adaptations directed by John Ford and Elia Kazan; westerns such as Ford's The Searchers (1956); and the songs of country/folk artists Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie. Springsteen also took note of rising British punk rock acts the Sex Pistols and the Clash, and new wave artists such as Elvis Costello.[m] Springsteen wanted a "leaner" and "angrier" sound compared to Born to Run,[11] explaining in his 2003 book Songs: "That sound wouldn't suit these songs or the people I was now writing about."[47]

The resulting Darkness on the Edge of Town is a less commercial record that emphasized the band as a whole and moved away from the Wall of Sound production of its predecessor. Springsteen favored guitar solos and limited Clemons' saxophone solos, which appear on only three of the ten tracks.[n] He explained: "The [guitar] leads fit better into the tone of Darkness than the saxophone did ... so consequently there was more [guitar] on the album."[49] Several songs emphasize choruses more than songs on earlier records, particularly "Badlands", "Prove It All Night", and "The Promised Land", while the verses are more anthemic than poetic. Springsteen's vocal style is also more meditative and less passionate on tracks such as "Racing in the Street", "Factory", and "Darkness on the Edge of Town".[46] Reviewers have noted that every song on side one of the original LP has a corresponding track on side two in the same sequence: "Badlands" and "The Promised Land" concern America and perceived hope, while "Adam Raised a Cain" and "Factory" concern father-son relationships.[24][50]

The record was of its time. We had the late-'70s recession, punk music had just come out, times were tough for a lot of the people I knew. And so, I veered away from great bar band music or great singles music and veered towards music that I felt would speak of people's life experiences.[12]

Margotin and Guesdon state that Darkness is "driven by raw energy and the immediacy of rock 'n' roll".[11] The writer Rob Kirkpatrick, who regarded it as Springsteen's "fiercest" record up to that point, said that with Darkness, Springsteen left R&B behind for 1970s hard rock.[46] The author Marc Dolan said in his 2012 book Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock 'n' Roll that the music was "whiter" than Springsteen's second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle (1973), but that Springsteen evoked 1960s black singing styles, such as James Brown on "Badlands" and Solomon Burke and Sam Moore on "Streets of Fire".[15] Michael Hann of The Quietus described the album as heartland rock.[51]

According to a 2019 essay by the scholars Kenneth Womack and Eileen Chapman, Darkness saw Springsteen "drive away from the beach and boardwalk and into the ethos of the American heartland".[52] Containing older and more mature characters than Born to Run, the songs on Darkness focus on ill-fortuned people who fight back against overwhelming odds;[11][53] they are frustrated and angry at their inability to achieve better lives.[54] Images of labor, class and class resentment, and troubled relationships with fathers, amongst various religious references, are featured throughout.[15][46] A 2008 analysis by Larry David Smith and Jon Rutter splits the album into three acts that describe "a tale of socioeconomic struggle and submission": the first details the characters' situations ("Badlands" to "Something in the Night"), the second concerns their struggles and search for hope ("Candy's Room" to "The Promised Land"), and the third finds them facing the consequences they must endure to succeed ("Factory" to "Prove It All Night"); "Darkness on the Edge of Town" acts as an epilogue, in which "Springsteen seals his narrative deal".[55]

Whereas Springsteen's previous albums were mostly set in and around the Jersey Shore area, the majority of Darkness is less characterized by a specific place and refers to other parts of the United States, from the generic American landscape to the Utah desert and Louisiana towns; although "Something in the Night" and "Racing in the Street" still take place around "the Circuit", a loop formed by Kingsley and Ocean Avenues, west of the boardwalk in Asbury Park.[15][46] Springsteen later referred to the album in his 2016 autobiography as "my samurai record, all stripped down for fighting".[56]

Side one

[edit]The album opens with "Badlands", a loud, anthemic rock song whose lyrics reflect a determination to succeed against oppression.[28][57] The lyrics warn against wasting time and suffering through "badlands" until they "start treating us good".[46] The autobiographical "Adam Raised a Cain" uses biblical references to portray a difficult father-son relationship, in which the son pays for the sins of the father.[31][46][57] Musically, it is a punk-influenced rock track driven by a heavy drumbeat and a riff played simultaneously by the guitars, bass, piano, and organ.[31] The author Peter Ames Carlin describes it as "tense, heavy-footed blues".[58] "Something in the Night" is a slower-paced song with dark lyrics about soul-searching in a car.[57][59] Thematically offering a post-Born to Run perspective,[58] depicting a moment where an individual's dreams are halted,[60] Springsteen reminds the listener that once someone has "something" it can easily be taken away.[46]

Described by Hann as the album's "most musically violent moment",[51] "Candy's Room" is a punk-influenced work led by drums.[61] Lyrically, it is a fantasy song in which suitors trade exquisite gifts for the title subject's affection.[46][57] The artist Karon Bihari, whom Springsteen briefly dated in the 1970s, claimed the song was about her.[61] "Racing in the Street" is a somber song with a melancholic stripped-down piano backing, with the rest of the instruments joining in over the course of the piece.[17][60] Telling the story of a man who will not let the bleakness of life ruin his love for car racing,[57] its characters resemble those of Born to Run's "Thunder Road", albeit two or three years later. The author Marc Dolan states that the song's themes are essential to the album, when the final verse states that individualistic efforts to succeed may be inadequate and ultimately lead to failure.[62]

Side two

[edit]"The Promised Land" is a country rock song with influences ranging from Van Morrison and Bob Dylan, to the Beatles and Hank Williams. Optimistic in tone, the narrator keeps his faith and strives for a "promised land" no matter what obstacles lie ahead.[43][60] Springsteen has said the song asks the question: "How do we honor the community and the place we came from?"[11] "Factory" provides commentary on the repetitive aspects of the working life,[63] depicting a factory-worker father, whose life is consumed by his job, but who works to provide for his family.[46] A partial tribute to his father,[63] Springsteen has said the song asks the question: "How do we honor the life that our brothers or sisters and parents lived?"[11] "Factory" is a rock and country-influenced ballad.[58][63]

"Streets of Fire" is a portrait of an outcast who has abandoned everything in order to defeat his inner demons. Musically, this slow rock song features both quiet and loud sections; Margotin and Guesdon note Springsteen's vocal performance for its "powerful intensity", being "on the verge of breaking".[58][64] "Prove It All Night" follows a couple who are about to get married.[65] The song's narrator tells the woman he loves to set aside her dreams and use determination to face the challenges that confront them as a couple.[46][60] It is an up-tempo rocker that builds in intensity.[66] The final track, "Darkness on the Edge of Town", represents a unification of the album's themes of lost love, hardships, and betrayal.[57] The narrator stands alone, has suffered misfortune and lost everything, but refuses to give up and stands tall.[33][60][67] Springsteen later said: "By the end of Darkness, I'd found my adult voice".[47] Primarily led by piano, the other instruments join in over the course of the song.[33]

Cover artwork

[edit]The cover shot and inner sleeve photographs for Darkness on the Edge of Town were taken by the then-unknown photographer Frank Stefanko inside his home in Haddonfield, New Jersey.[11] Stefanko, introduced to Springsteen by Patti Smith,[12] had not yet heard the album when the photo was taken and took the photos based on his perception of what Springsteen wanted.[68] In an interview with Entertainment Weekly in 2018, Stefanko said that his concept was to shoot Springsteen "as the young man that was standing in front of me".[69] On the cover, Springsteen appears as a tired man, hands in his jacket pockets, standing in a floral wallpaper-covered bedroom. Reviewers have acknowledged Springsteen's look as a physical manifestation of the album's songs and themes.[11][12][69] Springsteen himself recalled, "When I saw the picture I said, 'That's the guy in the songs.' I wanted the part of me that's still that guy to be on the cover. Frank stripped away all your celebrity and left you with your essence. That's what that record was about."[12] Stefanko felt the cover portrayed a sense of timelessness that resonated with listeners both on its release and in subsequent decades.[69] On the back cover, Springsteen appears without the jacket alongside the titles of the ten songs.[11] The packaging was designed by Andrea Klein.[41]

Release

[edit][Springsteen] wanted to be seen as having grown up. He felt that the whole Born to Run thing [had been] so hype driven. ... We eventually agreed the advertising [for Darkness] would have no copy except Bruce Springsteen—Darkness on the Edge of Town—The New Album, and the release date.[70]

Darkness on the Edge of Town was released on June 2, 1978,[50] nearly three years after Born to Run.[11][60] Its release coincided with new albums by the Rolling Stones (Some Girls), Bob Seger (Stranger in Town), and Foreigner (Double Vision).[29] Columbia Records promoted the album minimally at Springsteen's request;[11][71] following the media backlash of Born to Run and having gained full artistic control of his work, Springsteen initially wanted zero publicity for Darkness, comparing it to Columbia's strategy for Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding (1967).[70] He eventually allowed Columbia to promote it in select U.S. locations,[41] but refused to make promotional videos or live television appearances.[72]

Despite being highly anticipated, the album sold less than its predecessor,[73] but still reached number five on the U.S. Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart.[74] It remained on the chart for 167 weeks, selling more than three million copies.[11][13] In the U.K., it charted at number 14.[75] Elsewhere, the album reached the top ten in the Netherlands (4),[76] Canada (7),[77] Australia (9),[78] and Sweden (9),[79] number 11 in New Zealand,[80] 12 in Norway,[81] and 73 in Ireland.[82] Following the release of Born in the U.S.A., Darkness reappeared on the U.S. Billboard Top Pop Albums chart, peaking at number 167.[83] In 1999, the album was certified three times platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in the U.S.[84]

The album's singles were moderate hits according to the pop culture scholar Gillian G. Gaar.[13] The first single, "Prove It All Night" with "Factory" as the B-side, was released on May 23, 1978,[85] and extensively promoted by U.S. radio stations, reaching number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100.[65] "Badlands" was released as the second single on July 21,[86] and charted at number 42.[o][13] "The Promised Land", backed by "Streets of Fire", was released on October 13,[88][89] in the UK and Ireland and failed to chart.[43] Due to the album's dwindling commercial performance, Springsteen conducted an interview discussing the album and upcoming tour with Dave Marsh of Rolling Stone, in hopes of increasing publicity; he also hired Landau as his manager to assist in the campaign.[29] A billboard promoting Darkness was commissioned on Los Angeles's Sunset Boulevard, which Springsteen himself defaced on July 4.[29]

Springsteen and the E Street Band embarked on the Darkness Tour, which ran from May 23, 1978, to January 1, 1979.[11] Over 112 concerts, the band played 74 different songs. The setlists consisted of several songs from the Darkness sessions; songs that had yet to appear on a studio record, including "Fire", "Because the Night", and "The Fever", were regularly played and became fan favorites.[90] It was also the artist's largest tour up to that point. The band sold out stadiums and played shows upwards of three hours in length.[45][91] The tour attracted critical acclaim. Dolan called it "one of the most legendary tours" in rock history,[90] while the staff of Ultimate Classic Rock said the tour solidified Springsteen and the E Street Band as "one of the most exciting live acts in rock 'n' roll".[50] Two months after the tour's end, recording commenced for Springsteen's next album, The River.[91]

Critical reception

[edit]Contemporary reviews

[edit]| Initial reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| The Philadelphia Inquirer | |

| Record Mirror | |

| The Rolling Stone Record Guide(1979, 1st ed.) | |

| The New Rolling Stone Record Guide (1983, 2nd ed.) | |

| The Village Voice | B+[96] |

Darkness on the Edge of Town was met with generally favorable reviews on release.[45] According to the journalist Eric Alterman, critics who enjoyed Born to Run also liked Darkness, but "not as passionately or perhaps as innocently".[97] Several recognized the differences in production between the two records in both positive and negative lights.[71][98][99][100] Peter Silverton of Sounds magazine felt the production on Darkness displayed "the ill effects" of taking too much time to record, and in general, felt Darkness showed little advancement over Born to Run, with inferior songs and "only a fraction of the vitality".[101] ZigZag magazine's John Tobler argued the production made the record "sound like it belongs in another time and another place".[102] More positively, Robert Hilburn of Los Angeles Times said that Darkness "blends the rousing musical splendor and passionate, uplifting themes of Born to Run with even stronger production touches and a more consistent, probing group of songs".[100] A few believed the album improved with repeated listens.[98][103]

The music and performances of the E Street Band and Springsteen were well received. Some felt the production allowed Springsteen's voice to shine clearer.[p] The Boston Globe's Ernie Santosuosso said that the production exposed "a remarkably malleable voice" in Springsteen, recognized a "broader musical scope and dimension" than Springsteen's previous records, and praised his guitar work.[104] Critics were divided on the lyrical content. Some felt the songs were overly serious, bleak, and not as uplifting as those on Born to Run.[q] Others enjoyed the evolution in themes from prior records.[106] Hilburn said Darkness takes the lyrical themes of its predecessor and "zeroes in more deeply and productively on the key questions" raised on that record.[100] In The Village Voice, Robert Christgau commented on the narratives and the characters on "Badlands", "Adam Raised a Cain", and "Promised Land", writing that they showcased "how a limited genre can illuminate a mature, full-bodied philosophical insight". He deemed other songs, naming "Streets of Fire" and "Something in the Night", more impressionistic and overblown, revealing Springsteen to be either "an important minor artist or a very flawed and inconsistent major one".[96] More negatively, Creem's Mitchell Cohen and Crawdaddy's Peter Knobler, criticized the use of similar car themes as Born to Run and pondered if Springsteen was capable of writing about other topics.[105][107]

In Rolling Stone, Marsh hailed Darkness as a landmark rock and roll record that would one day be viewed in the same vein as records such as Jimi Hendrix's Are You Experienced (1967), Van Morrison's Astral Weeks (1968), and the Who's Who's Next (1971). Marsh remarked that the subject matter of the songs fulfilled the hype that surrounded Springsteen.[108] In NME, Paul Rambali said that Darkness "walks a fine line between the outrageous claims made on Springsteen's behalf and his tendency towards a grandiose, epic feel that encouraged those claims in the first place".[71] Hilburn argued the album affirmed Springsteen as a seminal rock figure of the 1970s, equaling the magnitude of Elvis Presley and the Rolling Stones.[100]

Darkness placed on several lists of the best albums of 1978, including at number one in NME.[109] It ranked number two in both Record Mirror and Rolling Stone, behind All Mod Cons by the Jam and Some Girls by the Rolling Stones, respectively. On Darkness, the latter magazine wrote: "Springsteen came back from the nether world with a dark, self-probing record that detailed the flip side of rock & roll exhilaration with unflinching honesty."[110][111] In Sounds, Darkness placed at number three, behind The Scream by Siouxsie and the Banshees and Give 'Em Enough Rope by the Clash.[112]

Retrospective reviews and legacy

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| American Songwriter | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| New Musical Express | 8/10[117] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide(1992, 3rd ed.) | |

| (The New) Rolling Stone Album Guide(2004, 4th ed.) | |

Darkness on the Edge of Town has become widely regarded as one of Springsteen's finest works,[121][122][123] with some considering it his best.[57][124][125][126] Reviewers have recognized Darkness as a harbinger for Springsteen's later career, forming the basis of his songwriting for the next decade, and foreshadowing efforts like Nebraska (1982) and The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995).[45][50][73] Some said the album embodies both Springsteen himself and the everyman appeal he stands for.[24][48] The Guardian's Keith Cameron argued that the album "remains the bedrock of both the ... Springsteen legend and the ethical code by which he continues to abide".[12]

Critics have called Darkness a timeless classic that speaks to wide-ranging audiences.[11][57][127] Entertainment Weekly's Sarah Sahim commended the combination of the raw music with the harsh details of universal life experiences, describing Darkness as an album "dedicated to the underdog", and the underdog in Springsteen's discography.[69] Brian Kachejian of Classic Rock History argued that the brilliance lies "not in the dark picture that Springsteen had painted about his life experiences, [but] in the small glimmers of hope that resounded in many of the songs".[57] Other critics highlighted Springsteen's growing maturity, and praised the more accessible lyrics.[r]

Darkness has continued to attract some mixed assessments. Music writers such as Colin Larkin and Gary Graff have criticized the album as being "anticlimactic" and for having "criminally flat" production, respectively.[129][116] Kirkpatrick opines that while one of Springsteen's best, Darkness suffers from comparisons to Born to Run, as well as from "occasional slow moments" like "Racing in the Street".[45] For the critic Steven Hyden, the album "sounds like a record designed by a rock critic [Landau]", and suffers from "cynical" songs that are "generally weighed down by undercurrents of depression and severe daddy issues". Nevertheless, he named Darkness his favorite Springsteen record, and one that is "the first, best example of Springsteen juxtaposing rousing rock music with miniaturist, miserabilist, Middle American storytelling".[130]

Rankings

[edit]Darkness on the Edge of Town has appeared on numerous best-of lists. In the opinion of Pitchfork's Mark Richardson, it "ranks with rock's classic albums".[131] In 1987, a panel of rock critics and music broadcasters polled for Paul Gambaccini's The Top 100 Rock 'n' Roll Albums of All Time, placed Darkness at number 59.[132] In 2003, it was ranked at number 150 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[133] rising to number 91 in a 2020 revision.[134] In 2013, the album was ranked 109th in a similar list by NME.[135] In a 2020 list compiling the 70 best albums of the 1970s, Paste placed Darkness at number 30.[136] The album was also included in the 2018 edition of Robert Dimery's book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[137]

Reissues

[edit]| The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| The Guardian | |

| Pitchfork | 9.5/10[131] |

| Record Collector | |

Darkness on the Edge of Town was first released on CD in 1984.[81] Additional CD reissues followed in 1990,[140] and by Sony BMG in 2008.[81] On November 16, 2010, the album was reissued as an expanded six-disc box set,[39][141] including three CDs and three DVD or Blu-ray discs. This contains a remastered version of the original album, a new two-CD album titled The Promise, containing 21 previously unreleased outtakes from the Darkness sessions, two live performance DVDs, and a "making of" documentary titled The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town.[141][142][143] The documentary was directed by Thom Zimny and features archival footage from the recording sessions and live performances from the era by Barry Rebo.[142]

The deluxe box set contains an 80-page spiral-bound reproduction of Springsteen's original notebooks documenting the original recording sessions containing alternate lyrics, song ideas, recording details, and personal notes.[142][143] The box was well received by critics[127][138][142] and won the Grammy Award for Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package at the 54th Annual Grammy Awards in 2012.[144]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Bruce Springsteen.[145]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Badlands" | 4:01 |

| 2. | "Adam Raised a Cain" | 4:32 |

| 3. | "Something in the Night" | 5:12 |

| 4. | "Candy's Room" | 2:45 |

| 5. | "Racing in the Street" | 6:52 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Promised Land" | 4:24 |

| 2. | "Factory" | 2:17 |

| 3. | "Streets of Fire" | 4:03 |

| 4. | "Prove It All Night" | 3:57 |

| 5. | "Darkness on the Edge of Town" | 4:28 |

| Total length: | 42:29 | |

Personnel

[edit]According to the liner notes,[145] except where noted.

- Bruce Springsteen – lead vocals, lead guitar, harmonica

The E Street Band

- Roy Bittan – piano

- Clarence Clemons – saxophone, backing vocals[31]

- Danny Federici – Hammond organ, glockenspiel

- Garry Tallent – bass guitar

- Steven Van Zandt – rhythm guitar, backing vocals[31]

- Max Weinberg – drums

Technical

- Bruce Springsteen – producer

- Jon Landau – producer

- Steven Van Zandt – assistant producer

- Jimmy Iovine – engineer, mixing

- Thom Panunzio – assistant engineer

- Chuck Plotkin – mixing

- Mike Reese – mastering

- Frank Stefanko – photography

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1978) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[78] | 9 |

| Canadian Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[77] | 7 |

| Irish Albums (IRMA)[82] | 73 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[76] | 4 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[80] | 11 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[81] | 12 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[79] | 9 |

| U.K. Albums Chart (OCC)[75] | 14 |

| U.S. Billboard Top LPs & Tape[74] | 5 |

| Chart (1985) | Peak position |

| U.S. Billboard Top Pop Albums[83] | 167 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[146] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[147] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| France | — | 50,000[148] |

| Germany | — | 100,000[149] |

| Italy | — | 100,000[150] |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[151] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[152] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[84] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Springsteen appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek magazines in the same week – October 27, 1975.[3] Time's article analyzed Springsteen as an artist, while Newsweek's focused on Springsteen's media hype.[4]

- ^ Springsteen could not record in a studio without a producer approved by Appel.[11]

- ^ In 1983, Appel sold his share back to Springsteen, giving Springsteen full ownership of his own music.[11]

- ^ CBS was the international distributor of Columbia Records outside of the United States.[21]

- ^ The authors Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon say that all songs except "Something in the Night" were recorded at the Record Plant.[11]

- ^ Other outtakes at this time included "City of Night", "The Ballad", "English Sons", "I'm Going Back", "Preacher's Daughter", and "Iceman".[25]

- ^ The mockup sleeve featured Springsteen on the front and Clemons on the back, both wearing all black attire.[27]

- ^ The song itself was written in early 1976 and was initially attempted during the first week of sessions.[32]

- ^ A track sequence dated January 16 ran:[34]

Side one: "Badlands", "Don't Look Back", "Candy's Room", "Something in the Night", "Racing in the Street";

Side two: "The Promised Land", "Adam Raised a Cane", "The Way", "Prove It All Night", "The Promise" - ^ The Pointer Sisters recorded the song in 1979, which reached number 2 in the US.[36]

- ^ Iovine instead produced and mixed Patti Smith's Easter (1978), the album on which "Because the Night" appeared.[44]

- ^ Plotkin was brought back to mix and coproduce subsequent albums.[11]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[11][12][13][46]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[15][20][31][48]

- ^ The B-side was "Streets of Fire", "Something in the Night", or "Candy's Room", depending on the country of release.[87]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[92][98][99][100]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[93][99][101][103][105]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[50][51][57][126][128]

References

[edit]- ^ Gerstenzang, Peter (August 25, 2015). "How Bruce Springsteen Made 'Born To Run' an American Masterpiece". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (November 17, 2005). "Bruce Springsteen's 'Born to Run' Turns 30". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (October 27, 2015). "Revisiting Bruce Springsteen's 'Time' and 'Newsweek' Covers". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 206.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Edwards, Henry (October 5, 1975). "If There Hadn't Been a Bruce Springsteen, Then the Critics Would Have Made Him Up; The Invention of Bruce Springsteen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 144.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 102–109.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cameron, Keith (September 23, 2010). "Bruce Springsteen: 'People thought we were gone. Finished'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gaar 2016, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 144.

- ^ a b c d e f Dolan 2012, pp. 149–152.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 51.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 120–123.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2012, p. 245.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (January 21, 2009). "The Band on Bruce: Their Springsteen". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 146.

- ^ Fish, Scott K. (April 1982). "Max Weinberg – Good Time on "E" Street". Modern Drummer. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c Robson, Paul (December 16, 2020). "The Genius of ... 'Darkness on the Edge of Town' by Bruce Springsteen". Guitar.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 149–153.

- ^ a b c d Dolan 2012, pp. 153–155.

- ^ a b Ruhlmann, William. "'Badlands' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2012, pp. 253–257.

- ^ Ponti, Aimsel (September 16, 2019). "Face the Music: Bill Chinnock's 'Badlands' Re-released in Original, Raw Form". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 151.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Marsh 1981, p. 275: "Ramrod".

- ^ a b Jurek, Thom (November 16, 2010). "The Promise – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 17, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 236.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 124–127.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 159, 163.

- ^ a b c d e Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 61–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 56–61.

- ^ a b Springsteen 2003, pp. 65–69.

- ^ a b Mendelsohn, Jason; Klinger, Eric (January 11, 2013). "Counterbalance No. 112: Bruce Springsteen's 'Darkness on the Edge of Town'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b c d e Gallucci, Michael; DeRiso, Nick; Lifton, Dave; Filcman, Debra; Smith, Rob (June 1, 2018). "'Darkness on the Edge of Town' at 40: Our Writers Answer Five Important Questions". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c Hann, Michael (June 4, 2018). "40 Years On: Bruce Springsteen's 'Darkness on the Edge of Town'". The Quietus. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Chapman, Eileen; Womack, Kenneth (2019). "Bruce Springsteen's Darkness on the Edge of Town: Hard Truths in Hard Rock Settings". Interdisciplinary Literary Studies. 21 (1). Penn State University Park: Penn State University Press: 1–3. doi:10.5325/intelitestud.21.1.0001. JSTOR 10.5325/intelitestud.21.1.0001. S2CID 194273496.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 262.

- ^ Hemmens, Craig (1999). "There's a Darkness on the Edge of Town: Merton's Five Modes of Adaptation in the Lyrics of Bruce Springsteen". International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice. 23 (1). Abingdon: Taylor & Francis: 127–136. doi:10.1080/01924036.1999.9678636. ISSN 0192-4036. ProQuest 236983768.

- ^ Smith, Larry David; Rutter, Jon (2008). "There's a Reckoning on the Edge of Town: Bruce Springsteen's Darkness on The River". Journal of Popular Music Studies. 20 (2). Ball State University: Wiley Online Library: 109–128. doi:10.1111/j.1533-1598.2008.00153.x.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kachejian, Brian (2021). "Why Springsteen's Darkness on the Edge of Town was His Best Album". Classic Rock History. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2012, pp. 250–252.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c d e f Gaar 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 132–135.

- ^ "Top Single Picks" (PDF). Billboard. June 3, 1978. p. 110. Retrieved February 14, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Dombal, Ryan (November 12, 2010). "Take Cover: Darkness on the Edge of Town Story — Photographer Frank Stefanko Talks About His Iconic 1978 Springsteen Album Cover". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Sahim, Sarah (June 8, 2018). "Springsteen's Darkness on the Edge of Town at 40: How the Iconic Album Cover was Made". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Heylin 2013, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Rambali, Paul (June 10, 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Ruhlmann, William. "Darkness on the Edge of Town – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Bruce Springsteen | full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Dutchcharts.nl – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 29, no. 21. August 19, 1978. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2012 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ a b Kent 1993, p. 289.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Norwegiancharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Irish Charts > Bruce Springsteen". irish-charts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Top Pop Albums – for the week ending March 16, 1985". Billboard. March 16, 1985. p. 75. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ Graff, Gary (May 23, 2023). "How Bruce Springsteen's 'Prove It All Night' Was Reborn Onstage". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Releases" (PDF). Music Week. July 22, 1978. p. 71. Retrieved August 21, 2024 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 110–113.

- ^ Strong 2006, p. 1021.

- ^ "Releases" (PDF). Music Week. October 14, 1978. p. 70. Retrieved August 22, 2024 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, pp. 160–166.

- ^ a b Gaar 2016, pp. 72–75.

- ^ a b "Albums". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 23, 1978. p. 27. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Cain, Barry (June 10, 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: 'Darkness on the Edge of Town'" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ McGee 1979, p. 365.

- ^ McGee 1983, p. 482.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (June 26, 1978). "Album: Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Alterman 2001, p. 102.

- ^ a b c "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. June 10, 1978. p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b c "Album Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. June 10, 1978. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b c d e Hilburn, Robert (June 2, 1978). "Springsteen's Heavy Mettle". Los Angeles Times. pp. 1, 24. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Silverton, Peter (June 10, 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town". Sounds. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Tobler, John (July 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town; Mink DeVille: Return To Magenta". ZigZag. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ a b Holdship, Bill (June 23, 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town (Columbia JC 35318)". Michigan State News. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Santosuosso, Ernie (June 8, 1978). "Record Reviews". The Boston Globe. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Cohen, Mitchell (September 1978). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town (Columbia)". Creem. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Rockwell, John (June 11, 1978). "Jagger, Springsteen and the New Angst". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 167: Peter Knobler, Crawdaddy.

- ^ Marsh, Dave (July 27, 1978). "Darkness on the Edge of Town". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ "NME's Best Albums and Tracks of 1978". NME. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Top 10 Albums" (PDF). Record Mirror. December 23, 1978. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Rolling Stone 1978 Critics' Awards". Rolling Stone. No. 281–282. December 28, 1978 – January 11, 1979. p. 11.

- ^ "Albums of the Year". Sounds. December 30, 1978. p. 12.

- ^ Gold, Adam (2010). "Bruce Springsteen: Darkness on the Edge of Town". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Kot, Greg (August 23, 1992). "The Recorded History of Springsteen". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Larkin 2011, p. 1,957.

- ^ a b Graff 1996, pp. 638–639.

- ^ Bailie, Stuart; Staunton, Terry (March 11, 1995). "Ace of boss". New Musical Express. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Williams, Richard (December 1989). "All or Nothing: The Springsteen Back Catalogue". Q. No. 39. p. 149. Retrieved February 12, 2024 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Evans 1992, p. 663.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, p. 771.

- ^ Taub, Matthew (November 8, 2022). "Bruce Springsteen: Every Album Ranked in Order of Greatness". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Studio Album, Ranked". Uproxx. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (July 29, 2015). "Bruce Springsteen Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Shipley, Al (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Album, Ranked". Spin. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Hann, Michael (May 30, 2019). "Bruce Springsteen's Albums – Ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b McCormick, Neil (October 24, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen: all his albums ranked, from worst to best". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Powers, Ann (November 15, 2010). "Review: Bruce Springsteen's 'The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, pp. 771–772.

- ^ Larkin 2011.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (January 7, 2014). "Overrated, Underrated, or Properly Rated: Bruce Springsteen". Grantland. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Richardson, Mark (November 17, 2010). "Bruce Springsteen: The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Gambaccini 1987.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2009. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Barker, Emily (October 25, 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 200–101". NME. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "The 70 Best Albums of the 1970s". Paste. January 7, 2020. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Dimery & Lydon 2018.

- ^ a b Williams, Richard (November 11, 2010). "'The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story' – Review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Staunton, Terry (November 20, 2010). "The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story – Bruce Springsteen". Record Collector. No. 383. Archived from the original on September 19, 2023. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 198.

- ^ a b Greene, Andy (August 26, 2010). "Springsteen Announces Massive 'Darkness' Set". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Jurek, Thom. "The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story [3 CD/3 DVD] – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Dombal, Ryan (August 26, 2010). "Bruce Springsteen to Release Darkness on the Edge of Town CD/DVD Box Set". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 2012: Winners and Nominees List". Los Angeles Times. March 22, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Darkness on the Edge of Town (liner notes). Bruce Springsteen. US: Columbia Records. 1978. JC 35318.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2008 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". Music Canada.

- ^ "Springsteen Tour Of Europe A Triumph Covering 10 Nations" (PDF). Billboard. June 20, 1981. p. 73. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Springsteen Tour Of Europe A Triumph Covering 10 Nations" (PDF). Billboard. June 20, 1981. p. 40. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Zinsenheim, Roy (November 26, 1988). "New Marketing Strategy Sees Music On New Stands" (PDF). Music & Media. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter Darkness on the Edge of Town in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- ^ "British album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Darkness on the Edge of Town". British Phonographic Industry.

Sources

[edit]- Alterman, Eric (2001). It Ain't No Sin to Be Glad You're Alive: The Promise of Bruce Springsteen. Boston: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-31603-917-8.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2012). Bruce. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-9182-8.

- Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2018). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-78840-080-0.

- Dolan, Marc (2012). Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock 'n' Roll. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39308-135-0.

- Evans, Paul (1992). "Bruce Springsteen". In DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James; George-Warren, Holly (eds.). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (3rd ed.). New York City: Straight Arrow Publishers, Inc. pp. 663–665. ISBN 978-0-679-73729-2.

- Gaar, Gillian G. (2016). Boss: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band – The Illustrated History. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-76034-972-4.

- Gambaccini, Paul (1987). The Top 100 Rock "n" Roll Albums of All Time. New York City: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-51756-561-2.

- Graff, Gary (1996). "Bruce Springsteen". In Graff, Gary (ed.). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-0-7876-1037-1.

- Heylin, Clinton (2013). E Street Shuffle: The Glory Days of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band (First American ed.). New York City: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-02662-3.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5.

- Kirkpatrick, Rob (2007). The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27598-938-5.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bruce Springsteen". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2020). Bruce Springsteen All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. London: Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-78472-649-2.

- Marsh, Dave (1981). Born to Run: The Bruce Springsteen Story. New York City: Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-440-10694-4.

- McGee, David (1979). "Bruce Springsteen". In Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John (eds.). The Rolling Stone Record Guide (1st ed.). New York City: Random House/Rolling Stone Press. pp. 365–366. ISBN 978-0-394-73535-1.

- McGee, David (1983). "Bruce Springsteen". In Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Record Guide (2nd ed.). New York City: Random House/Rolling Stone Press. pp. 482–484. ISBN 978-0-394-72107-1.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "Bruce Springsteen". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). (The New) Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). London: Fireside Books. pp. 771–773. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8. Portions posted at "Bruce Springsteen > Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2016). Born to Run. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-4151-5.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2003). Songs. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0862-6.

- Strong, Martin C. (2006). "Bruce Springsteen". The Great Rock Discography. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84195-860-6.

External links

[edit]- Darkness on the Edge of Town at Discogs (list of releases)

- Album lyrics and audio samples

- Collection of album reviews