Candlepin bowling

| |

| First played | Circa 1880, Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | Yes and individual |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Bowling |

| Equipment | Candlepins, candlepin bowling ball, bowling lane |

| Venue | Bowling alley |

| Glossary | Glossary of bowling |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | New England, The Maritimes |

Candlepin bowling is a variation of bowling that is played primarily in the Canadian Maritime provinces and the New England region of the United States. It is played with a handheld-sized ball and tall, narrow pins that resemble candles, hence the name.

Comparison to ten-pin bowling

[edit]As in other forms of pin bowling, players roll balls down a 60 foot, wooden or synthetic lane, to knock down as many pins as possible. Differences between candlepin bowling and ten-pin bowling include:

- Candlepin involves three rolls per frame, rather than two rolls as in ten-pin.

- Candlepin balls are much smaller, being 4+1⁄2 inches (11.43 cm) in diameter and have a maximum weight of 2 lbs. 7 oz. They are almost identical in weight to a pin, as opposed to ten-pin balls whose maximum allowable weight is more than four times that of a pin.

- No oil is applied to the lane, so the ball does not skid but rolls all the way down the lane.

- Candlepin balls lack finger holes.

- Candlepins are thinner (hence the name "candlepin"), which increases the amount of space between pins, further reducing scoring.

- Fallen pins ("wood") are not cleared away between rolls during a frame, so long as the entire pin stays behind the "dead wood" line, which is 24 inches in front of the "head pin" spot. Wood in the gutters is "dead wood", which means that if the ball makes its first contact with it, the pins felled do not count, nor are they re-spotted.

History

[edit]

The International Candlepin Bowling Association (ICBA) website states that candlepin bowling was first played in 1880 in Worcester, Massachusetts,[5] thought to have been developed by Justin White, owner of a billiards and bowling hall.[6] A 1987 Sports Illustrated article stated the game was invented in 1881 in that town by one John J. Monsey, a billiards player,[7] who is recognized for standardizing the game.[6] A 1891 newspaper notice[8] shows the incremental introduction of a single "candle-pin bowling set" into a bowling alley originally hosting other types of bowling. In 1906, Monsey created the National Duckpin and Candlepin Congress, which regulated ball size, pin shape and size, and lane surface characteristics, facilitating formation of leagues and other competitions.[6]

Originally, pins were inch-thick dowels, resembling candles, thought to give rise to the name, candlepins.[7] An 1888 newspaper article referred to 2-inch thick pins.[9] Both were thinner than modern candlepins which are specified to be 2+15⁄16 inches (74.6 mm) thick.[1] In the late 1960s, plastic candlepins began to replace wood candlepins, a change that some thought required a change in game strategy.[6]

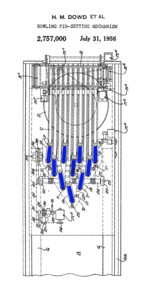

In 1947, lawyers Howard Dowd and Lionel Barrow overcame the need for human pinsetters by inventing the first automatic candlepin pinsetter,[6] called the "Bowl-Mor", the two inventors receiving a patent that issued in 1956.[4]

Stations WHDH-TV/5 & the later licensee of channel 5, WCVB-TV, aired candlepin bowling's first televised show from 1958 through 1996, and in 1964, The Boston Globe launched its own annual candlepin tournament.[6] In 1965, the World Candlepin Bowling Council (WCPC) began its Hall of Fame, inducting WCVB commentator Don Gillis in 1987.[6] In 1973, station WHDH began airing Candlepins for Cash, allowing contestants to earn a jackpot by rolling a strike.[6]

In 1986, the International Candlepin Bowling Association (ICBA) was formed.[6]

The highest sanctioned candlepin score is 245, achieved in 1984 (Ralph Semb, Erving, Massachusetts) and again on May 13, 2011 (Chris Sargent, Haverhill, Massachusetts).[10]

Game play

[edit]Candlepins are 15.75 inches (40.0 cm) high and 2+15⁄16 inches (74.6 mm) thick in diameter. Balls are 4.5 in (11 cm) in diameter and lighter than a single candlepin.[1][2]

A candlepin bowling lane, almost identical to a tenpin bowling lane, has an approach area of 14 to 16 feet (4.3 to 4.9 m) for the player to bowl from, and then the lane proper, a maple surface approximately 41 inches (1.05 m) wide, bounded on either side by a gutter (or "channel" or trough). The lane is separated from the approach by a "foul line" common to most bowling sports, which players must not cross. At the far end of the lane are the pins, 60 feet (18 m) from the foul line to the center of the headpin (or pin #1), placed by a pinsetter machine which occupies space both above and behind the pins. Unlike a tenpin lane, which has a level surface from the foul line to the back end of the lanebed's "pin deck", a candlepin lane has a hard-surfaced "pin plate" where the pins are set up, with the pin plate depressed 7⁄16 inch (11 mm) below the lanebed forward of it. The pin plate can be made from hard-surfaced metal, phenolic, high density plastic, or a synthetic material. Behind the pin plate area is a well-depressed "pit" area for the felled pins and balls to fall into. A heavy rubber backstop, faced with a black curtain, catches the flying pins and balls so they drop into the pit. Generally there is seating behind the approach area for teammates, spectators, and score keeping.

The candlepins themselves are 15+3⁄4 inches (40 cm) tall, have a cylindrical shape which tapers equally towards each end (and therefore have no distinct "top" or "bottom" end, unlike a tenpin), giving them an overall appearance somewhat like a candle, and have a maximum weight of 2 lb 8 oz (1.1 kg) apiece.[11] Candlepin bowling uses the same numbering system and shape for the formation within the ten candlepins are set, as the tenpin sport. Also, as in tenpin bowling, due to the spacing of the pins (12 inches or 30 centimetres, center to center), it is impossible for the ball to strike every one. However, while in tenpin a well-placed ball (usually between the head pin and the 2 or 3 pin) may knock down all ten pins (a "strike" if on the first ball in a frame) from the chain reaction of pin hitting pin, in candlepins the smaller thickness of the pins makes throwing a strike extremely difficult. To count, the pin must be knocked over entirely; in unlucky circumstances, a pin may wobble furiously, or even more frustratingly, be "kicked" to the side by several inches, yet come to rest upright, thus not being scored (or reset to its original position for any remaining throws, though it may be knocked over by subsequent balls). It is even possible for a toppled pin to bounce off a side "kickback", and return to a standing position on the lane's pin deck. However, if a fallen pin returns to a standing position, the pin is still counted as fallen and is played as live wood.[11]

In addition to the foul line, there is a line 10 feet (3.0 m) further down the lane called the lob line, and the ball must first contact the lane at any point on the bowler's side of it, be it on the approach or the first ten feet of the lanebed. Any "airborne" ball delivery not making contact with the approach or lanebed short of the "lob line" constitutes a violation of this rule, and is termed a lob with any pins knocked down by such a ball not counting—and such pins are not reset if the lobbed ball was not the third and last shot for that player in that box.

Also, a third line, centered 61 cm (24 in) forward of the head pin (number-1 pin) spot is the dead wood line, which defines the maximum forward limit that any toppled pins ("wood") can occupy and still be legally playable ("live wood").

The ball used in candlepins has a maximum weight of 2 lb 7 oz (1.1 kg), and has a diameter of 4.5 in (11 cm),[1] making it the smallest bowling ball of any North American bowling sport. The nearly identical weight of the ball, when compared to that of just one candlepin 2 lb 8 oz (1.1 kg),[1] causes balls to deflect when impacting either standing or downed pins.

A game of candlepin bowling, often called a string in New England, is divided into ten rounds, each which is most commonly referred to as a box, rather than a "frame" as in tenpin bowling. In each normal box, a player is given up to three opportunities to knock down as many pins as possible. In the final box, three balls are rolled regardless of the pincount, meaning three strikes can be scored in the 10th box.

One unique feature of the candlepin sport is that fallen pins, called wood, are not removed from the pin deck area between balls, unlike either the tenpin or duckpin bowling sports. The bowler, before delivering the second or third ball of a box, must also wait until all wood on the deck comes to rest. Depending on where the fallen pins are located on the pindeck and their angle(s) after their movement ceases, the wood can be a major help, or obstacle—partly due to the ball having nearly the same weight as one candlepin—in trying to knock down every single standing pin for either a spare or "ten-box" score in completing a round.

In each of the first nine boxes, play proceeds as follows: The first player bowls his first ball at the pins. The pins he knocks down are counted and scored. Then the player rolls a second and a third ball at any remaining targets. If all ten pins are knocked down with the first ball (a strike), the player receives ten points plus the count on the next two rolls, the pins are cleared, a new set placed. If all ten pins are knocked down with two balls (a spare), the player receives 10 points plus the count of the next ball, pins are cleared and reset. If all three balls are needed to knock all the pins down, the score for that frame is simply ten, and known in New England as a ten-box.[13] If more than one player is playing on the same lane at the same time, bowlers will typically roll two complete boxes before yielding the lane to the next bowler.

In the tenth box, play is similar, except that a player scoring a strike is granted two additional balls, scoring a spare earns one additional ball. Three balls are rolled in the tenth box regardless.[14]

In league play, a bowler may roll two or five boxes at a time, depending on the rules of the league. The five box format is sometimes called a "speed league", and this format is also typical for tournament play. When a bowler is rolling blocks of five boxes, each period is typically called a "half".

Fouls

[edit]A foul (scored by an F on some computer scoring systems) refers to a ball that first rolls into the gutter and then strikes deadwood (felled pins resting in the gutter) or hops out of the gutter and strikes a standing pin, a "lob"-bed ball that touches neither the approach nor lane in the three meters' distance of lanebed before the lob line, or as in tenpins and duckpins, a roll made when a bowler's foot crosses over the foot foul line. Special scoring comes into play.

A foul always scores zero (0) pinfall for that ball's delivery. A player may reset the pins after a foul on the first or second ball provided no pins have legally been felled in that box. Therefore, if on the first ball there is a foul or zero, and on the second ball the bowler fouls and knocks down pins, the pins may be reset, allowing the bowler an opportunity to score on their third ball. Knocking down all ten pins after resetting immediately following a foul in the first ball results in a spare. Fouling on all three attempts scores a zero box.

If the first ball knocked down at least one pin, the rack can not be reset because of a subsequent foul. Those pins felled by a foul ball (a ball rolled into the gutter, a lobbed ball, a ball delivered by a bowler over the foot foul line)—whether standing, playable wood, or pins in the gutter—remain down and reduce the maximum number of pins to be counted for the box. Therefore, if there are six pins standing after the first ball, a foul on the next ball that manages to knock down the remaining six pins means that the frame is finished, with a score of 4. However, if the foul ball knocked down only some of the six standing pins, a third ball may still be rolled to attempt to knock down the remaining upright pins. In this example, the raw score might appear to be "4 4 2 = X", but after adjusting for the foul second ball, the true score is "4 F 2 = 6". Similar logic holds when rolling two good balls and fouling in the third attempt: the frame is over and only the pins felled in the first two attempts are recorded for the score for that box.[11]

While most candlepin alleys have automated scoring systems, and thus know when to trigger a candlepin pinsetter to clear and reset pins; other alleys, especially older ones that require a manual method to initiate the pinsetter will have a button, or floor-mounted foot pedal switch, to start the pinsetter's electrically-powered clearing and resetting of pins. Before the era of the Bowl-Mor powered pinsetter units' debut in 1949,[15] as with ten-pin, candlepins were set by workers called "pinboys".

Scoring

[edit]One point is scored for each pin that is knocked over. So, in a hypothetical game, if player A felled 3 pins with their first ball, then 5 with their second, and 1 with the third, they would receive 9 points for that box. If player B knocks down 9 pins with their first shot, but misses with their second and third, they also score 9.

If a player fells all ten pins in a single box with two or less throws (just as in tenpins) bonuses are awarded for a strike or spare. A strike is achieved with just the first delivery downing all ten pins, with a spare needing two throws, again just as in the tenpin sport.

In a strike, the bonus for a box adds 10 plus the amount of pins felled by the next two shots. In a spare, the bonus for a box adds 10 plus the amount of pins on the next shot.

If all ten pins are felled by rolling all three balls in a box, the result is a ten-box, marked by an X (as in the Roman numeral for ten) but no additional points are awarded. (In tenpin bowling, a strike is often scored with an X).

Although never achieved, [10] the maximum possible score in a single game/string of candlepins is 300. This is scored by bowling 12 strikes: one in each box, and a strike with both bonus balls in the 10th box. In this way, each box will score 30 points (see above: scoring: strike).

This scoring system, except for the scoring sheet's appearance and the graphic symbols used to record strikes, spares and 10-boxes,[16] is identical to that of duckpins, as it is the other major form of bowling that uses three balls per frame.

Scoring sheet

[edit]

The candlepin scoring sheet is different from either tenpins or duckpins, in that it is usually oriented vertically, with two columns of squares in a two-square-wide, ten-square-tall arrangement to score one string for one player. The left-hand column is used to detail the "per-box" score, with the cumulative total recorded down the sheet as each box is rolled in the right-hand column of squares, in a top-down order from the first box to the tenth.

Spares and strikes are also marked uniquely in candlepins. Spares are recorded in a box by coloring in the left upper corner of the appropriate left-hand square (using a triangular shape to "fill-in the corner"). If a strike is recorded, opposing corners of the left-hand square are similarly colored in, while leaving sufficient space between the "filled-in" opposing corners, to record the score from the two succeeding balls' "fill" total for the strike. A common (albeit unofficial) practice is to mark a strike on a strike's bonus ball (double strike) by shading in the remaining two corners of the first strike.

Calculating scores

[edit]Correct calculation of bonus points can be a bit tricky, especially when combinations of strikes and spares come in successive boxes. In modern times, however, this has been overcome with automated scoring systems. When a scoring system is "automated", the bowler only has to bowl. It keeps score and will reset the pinsetter after three balls are thrown or all 10 pins have been knocked down. If a scoring system is "semiautomated", the bowler has to enter the score but the computer will keep track of it. The bowler needs to press a button at the end of the ball return to receive a new "rack" of pins.

Terminology

[edit]Many candlepin terms denote combinations of pins left standing after the first ball has been rolled. Examples of these terms include:[17]

- Head pin

- The 1-pin, which is in front of the other pins.[17]

- King pin

- The 5-pin, which is in the center of the pins, and directly behind the head pin.[17]

- Wood

- The fallen pins lying between the standing pins, often strategically used to knock down multiple standing pins which can be far apart.

- Deadwood

- Fallen pins lying in the gutter, or on the lane either touching, or to the bowler's side of the Deadwood Line. Deadwood on the lane must be removed before the bowler may roll their next ball, while Deadwood in the gutter is left in place. If a delivered ball should strike any Deadwood prior to hitting any wood or standing pins on the lane, then that ball is considered "dead" and any pins felled by it do not count to the bowler's score.

- Mark

- Spare or strike.

- Four Horsemen

- Four pins in a diagonal line, from the head-pin outward;[17] if the 1–2–4–7, it is known as "Four horsemen, left side," and if the 1–3–6–10, it is known as "Four horsemen, right side." The usual tenpin term for a spare leave of this kind is a "picket fence" (used for a different spare leave in candlepins) or "clothesline".

- Spread Eagle

- A split configuration consisting of the 2–3–4–6–7–10, caused by the first shot striking the head pin too directly, leading to a failure to scatter the pins.[17] Video of the "spread eagle" being left, then converted

- Diamond

- Four pins that form a diamond-shaped configuration,[17] either the 2–4–5–8, known as "left-side diamond," the 3–5–6–9, known as "right-side diamond", or the 1–2–3–5, known as the "center diamond" (this same configuration, for any of the three configurations mentioned, is usually referred to as a "bucket" in standard ten-pin bowling, and while it is very difficult to convert into a spare in candlepin bowling, in ten-pin bowling a spare is usually made from it by an experienced bowler).

- Half Worcester

- Perhaps the most distinctive term used in the game. This results when the first shot strikes either the 2-pin or 3-pin too directly, and knocks down (or punches out) only that pin and the one immediately behind it;[17] when only the 2- and 8-pins fall it is a "Half Worcester Left", and when only the 3- and 9-pins fall it is a "Half Worcester Right". According to legend, the term was coined when a team from Worcester and a team from Boston were competing in the semifinal round of a statewide tournament held sometime in the 1940s; late in the last match of the round, needing a mark, one of the bowlers on the Worcester team "punched out" only two such pins with his first ball, prompting a member of the Boston team to taunt him by saying, "You're halfway back to Worcester!"[18] It is sometimes said that a player will get "one a game" referring to the Half Worcester.

- Full Worcester

- Knocking down 2–3–8–9, or two Half Worcesters.

- Quarter Worcester

- Another term derived from the Half Worcester, knocking down half as many pins—either just the 2-pin or just the 3-pin.

- Triple

- A three-game series. When spoken, it follows a rough total of the series, such as "500-triple," meaning the bowler rolled 500 or more for three games. Triple can also refer to three consecutive Strikes rolled by a bowler – other forms of Bowling would call this a "Turkey".

- Hammer

- A strike where all 10 pins are felled in an almost simultaneous fashion.

- Hi-Lo-Jack

- A leave of the # 1, 7 and 10 pins. This shot was also set up for both competitors to attempt at the conclusion of the weekly WCVB/WHDH "Candlepin Bowling" program hosted by Don Gillis/Jim Britt which ran from 1958-1996. For each week the shot was not made, the "Hi-Lo-Jackpot" would increase by $25.00.

- Woolworth Split

- a leave where only the # 5 and 10 pins remain. This is a reference to the once-ubiquitous "5 and 10" stores found in many towns across the United States.

In popular culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]In The New York Times, reviewer Cathleen Schine called Elizabeth McCracken's 2019 novel Bowlaway "a history of New England's candlepin bowling", the sport serving as "the novel's unlikely, crashing, arrhythmic leitmotif".[19]

Film

[edit]The 2023 film The Holdovers shows the characters playing candlepin bowling.[20][21]

See also

[edit]- Stasia Czernicki (1922–1993)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e New Hampshire Candlepin Bowling Association (2013). "Candlepin Bowling Rules / Pin specifications and ~ / Ball specifications". Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. 2013 date estimated based on earliest archive date.

- ^ a b "Basics of candlepin vs. tenpin bowling". The Boston Globe. May 4, 2014. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014.

- ^ "Candle-Pin Bowlers". The Boston Daily Globe. March 8, 1889. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019.

- ^ a b U.S. Patent 2,757,000, Dowd, Howard M. and Barrows, Royal L., "Bowling Pin-Setting Mechanism", issued July 31, 1956

- ^ "Candlepin Bowling History". Candlepin.org. International Candlepin Bowling Association. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eaton, Perry (August 6, 2015). "A year-by-year history of candlepin bowling". Boston.com. Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Campbell, Douglas (December 7, 1987). "The Leading Light of Candlepin Bowling". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Sporting Notes". The Boston Daily Globe. March 17, 1891. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019.

- ^ "Sporting Miscellany". The Boston Daily Globe. May 9, 1888. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "Haverhill man matches candlepin bowling world record". The Herald News. Fall River, Massachusetts. May 18, 2011. Archived from the original on 2019-02-07.

- ^ a b c International Candlepin Bowling Association (June 2010). "Candlepin Bowling Rules". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Find a center". Candlepin.org. International Candlepin Bowling Association (ICBA). Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019. Interactive map through MapMaker.com.

- ^ "Maine Candlepin Bowling". www.mainecandlepinbowling.com. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ International Candlepin Bowling Association. "Candlepin Bowling Scoring Rules". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Bowling pin-setting mechanism: US 2757000 A". Google Patents. 31 July 1956. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Massachusetts Bowling Association – How to Score" (PDF). www.masscandlepin.com. Massachusetts Bowling Association. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g International Candlepin Bowling Association. "Candlepin Language". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Klaft, Lynne (7 April 2007). "On a roll: Old-time fun, challenge of candlepin bowling enjoying a resurgence". Worcester Telegram & Gazette. Worcester, MA. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- ^ Schine, Cathleen (February 12, 2019). "A Dark Fairy Tale of American Oddballs and Candlepin Bowling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019.

- ^ "For director Alexander Payne, making 'The Holdovers' felt like 'coming home'". www.wbur.org. November 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Holdovers isn't a period film—or so Alexander Payne tells himself". AV Club.

External links

[edit]- "ICBA Rules and Regulations". candlepin.org. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022.

- Eaton, Perry (August 6, 2015). "A year-by-year history of candlepin bowling". Boston.com. Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016.

- Map showing locations of Candlepin, Duckpin, 5 Pin and 9 Pin Centers of North America