Canadian Museum for Human Rights

Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne | |

| |

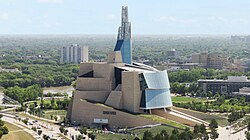

Canadian Museum for Human Rights in 2014 | |

| |

| Established | 13 March 2008 |

|---|---|

| Location | The Forks, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada |

| Type | Human rights museum |

| Visitors | 295,300 (2016/17)[1] |

| Founder | Israel Asper and The Asper Foundation |

| President | Isha Khan |

| Owner | Government of Canada[2] |

| Website | www |

Building details | |

| General information | |

| Groundbreaking | 19 December 2008 |

| Construction started | 2009 |

| Cost | $351 million |

| Height | |

| Observatory | 100 m (328.08 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | alabaster, basalt rock, glass, Tyndall limestone, steel |

| Floor count | 8 |

| Floor area | 24,155 m2 (5.97 acres) |

| Lifts/elevators | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Antoine Predock |

| Awards and prizes | 14 national & international awards related to its architecture and construction |

| Other information | |

| Number of restaurants | 1 (ERA Bistro) |

| Agency overview | |

| Type | Crown corporation |

| Minister responsible | |

| Key document |

|

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR; French: Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne) is a Canadian Crown corporation and national museum located in Winnipeg, Manitoba, adjacent to The Forks. The purpose of the museum is to "explore the subject of human rights with a special but not exclusive reference to Canada, to enhance the public's understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others and to encourage reflection and dialogue."[3][4]

Established in 2008 through the enactment of Bill C-42, an amendment of The Museums Act of Canada,[5][4] the CMHR is the first new national museum created in Canada since 1967, and it is Canada's first national museum ever to be located outside the National Capital Region.[6] The Museum held its opening ceremonies on 19 September 2014.[3]

The Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is the charitable organization responsible for attracting and maintaining all forms of philanthropic contributions to the Museum.[7]

History

[edit]Development

[edit]The late Izzy Asper—a Canadian lawyer, politician, and founder of the now-defunct media conglomerate Canwest Global Communications—is credited with the idea and vision to establish the CMHR,[8][9] having first come up with the idea on 18 July 2000 to build the museum.[10] Asper hoped it would become a place where students from across Canada could come to learn about human rights. He also saw it as an opportunity to revitalize downtown Winnipeg and increase tourism to the city, as well as to raise understanding and awareness of human rights, promote respect for others, and encourage reflection, dialogue, and action. Working on his idea for three years, Asper had a thorough feasibility study conducted by museum experts from around Canada.[10]

In 2003, Asper established the Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, a private charitable organization, to build the CMHR.[8] On 17 April, the 21st anniversary of Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms, an event was held at The Forks in Winnipeg where Asper first publicly announced the intent to create the CMHR. It was announced as a joint partnership between The Asper Foundation and the governments of Canada, Manitoba, and of Winnipeg, as well as land donated by the Forks Renewal Corporation.[11][10] Prime Minister Jean Chrétien committed the first $30 million towards the capital cost, and private fundraising was soon overseen by the Friends of the CMHR.[10] The Asper Foundation donated $20 million.

Later that year, on 7 October, Izzy Asper died suddenly at the age of 71 on his way to announce the architectural competition in Vancouver for the CMHR's design. Vowing to continue to develop the museum, his family and The Asper Foundation continued with the project, now spearheaded by Izzy's daughter, Gail Asper.[3] Two weeks later, the symbolic sod-turning ceremony was held at The Forks and the architectural competition announced.[10]

The Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights launched the international architectural competition for the design of the CMHR, one of Canada's largest-ever juried architectural competitions. 100 submissions from 21 countries worldwide were submitted.[12][13] The judging panel chose the design submitted by Antoine Predock, an architect from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Meanwhile, Ralph Appelbaum, head of Ralph Appelbaum Associates, the world's largest museum design company, was hired to develop the CMHR's exhibits.[12]

Legislation, construction, and opening

[edit]On 20 April 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced the Government of Canada's intention to make the CMHR into a national museum. On 13 March 2008, Bill C-42, An Act to amend the Museums Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts,[14] received royal assent in Parliament with support from all political parties, creating the Canadian Museum for Human Rights as a national museum.[15]

By the middle of 2008, a government-funded opinion research project had been completed by the TNS/The Antima Group. The ensuing report[16]—based primarily on focus group participants—listed the following: topics that the CMHR might cover (not in order of preference); key milestones in human rights achievements, both in Canada and throughout the world; current debates about human rights; and events where Canada showed a betrayal or a commitment to human rights.

Before construction could begin, archeologists, in consultation with Elders, conduct an extensive excavation and recovered over 400,000 artifacts in the ancestral lands.[12]

The groundbreaking ceremony was held at the site of the CMHR on 19 December 2008,[17] and official construction on the site began in April the following year. (Construction was initially expected to be completed in 2012.)[18] The chair of the board resigned before his term was up, and a new interim chair was appointed.[19][20]

On 3 July 2010, Queen Elizabeth II—having personally selected a stone from Runnymede, the English meadow where the Magna Carta was sealed in 1215—unveiled the Museum's cornerstone, inscribed with a message from the Queen and encased in Manitoba Tyndall stone.[12]

The last of the 1,669 custom-cut pieces of glass was installed in September 2012, and within a few months the base building was completed.[12] The Museum's inauguration took place in 2014.[21][22] Also in 2014, a stretch of road in front of the CMHR was named Israel Asper Way.[23]

The museum's official grand opening on 20 September 2014 was protested by several activist groups, who expressed the view that their own human rights histories had been inaccurately depicted or excluded from the museum.[3] The First Nations musical group A Tribe Called Red, who had been scheduled to perform at the opening ceremony, pulled out in protest against the museum's coverage of First Nations issues.[24]

Funding

[edit]

Funding for the capital costs of the CMHR is coming from three jurisdictions of government, the federal Crown, the provincial Crown, and the City of Winnipeg, as well as private donations. The total budget for the building of the exterior of the CMHR and its contents was $310 million as of February 2011. At the time of its opening in September 2014, the cost of the museum was approximately $351 million.[25]

To date, the Government of Canada has allocated $100 million; the Government of Manitoba has donated $40 million; and the City of Winnipeg has donated $20 million.[26] The Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, led by Gail Asper, have raised more than $130 million in private donations from across Canada toward a final goal of $150 million.[27] These private-sector pledges include $4.5 million from provincial crown corporations in Manitoba and $5 million from the Government of Ontario.[28] The Canadian Museum for Human Rights has requested an additional $35 million in capital funding from the federal government to cover shortfalls. In April 2011, the CMHR received an additional $3.6 million from the City of Winnipeg, which was taken from a federal grant to the city in lieu of taxes for the museum.[29]

The CMHR's operating budget is provided by the government of Canada, as the CMHR is a national museum. The estimated operating costs to the federal government are $22 million annually. In December 2011, the CMHR announced that due to rising costs for the interior exhibits of the museum, the total construction cost had increased by an additional $41 million to a new total of $351 million.[30] In July 2012, the federal and provincial governments agreed to further enhance the capital funding to the CMHR by up to $70 million, through a combination of a federal loan and a provincial loan guarantee. This newest funding was essential for the completion of the interior exhibits so that the museum could officially open in 2014, already two years behind schedule.[31]

Architecture

[edit]

The building's ground floor provides orientation and meeting space, a gift shop, restaurant, and visitor services. Galleries on different levels are linked by dramatic backlit alabaster ramps, including the Hall of Hope. There is also a Garden of Contemplation, which has still-water pools punctuated by dramatic black Mongolian basalt.[32]

Beginning with the Great Hall, the visitor experience culminates in the Israel Asper Tower of Hope, a 100-metre glass spire protruding from the CMHR that provides visitors with views of downtown Winnipeg.[33]

Design and construction process

[edit]In 2003, the Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights launched an international architectural competition for the design of the CMHR. 100 submissions from 21 countries worldwide were submitted.[13] The judging panel chose the design submitted by Antoine Predock from Albuquerque, New Mexico.

His vision for the CMHR was a journey, beginning with a descent into the earth where visitors enter the CMHR through the "roots" of the museum. Visitors are led through the Great Hall, then a series of vast spaces and ramps, before culminating in the "Tower of Hope", a tall spire protruding from the CMHR.[33] He has been quoted as saying: "I'm often asked what my favorite, my most important building is.... I'm going on record right now... 'This is it.'"[34]

Predock's inspiration for the CMHR came from the natural scenery and open spaces in Canada, including trees, ice, northern lights, First Nations peoples in Canada, and the rootedness of human rights action. He describes the CMHR in the following way:[35]

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is rooted in humanity, making visible in the architecture the fundamental commonality of humankind-a symbolic apparition of ice, clouds and stone set in a field of sweet grass. Carved into the earth and dissolving into the sky on the Winnipeg horizon, the abstract ephemeral wings of a white dove embrace a mythic stone mountain of 450 million year old Tyndall limestone in the creation of a unifying and timeless landmark for all nations and cultures of the world.

The base building was complete since the end of 2012. Throughout the foundation work of the CMHR, medicine bags created by elders at Thunderbird House, in Winnipeg, were inserted into the holes made for piles and caissons to show respect for Mother Earth. The CMHR website had two webcams available for the public to watch the construction as it progressed.

For the construction of the Hall of Hope, full of illuminated alabaster ramps, more than 3,500m² and 15,000 tiles of alabaster were used, making it the biggest project ever done with alabaster.[36][37]

On 3 July 2010, Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, unveiled the building's cornerstone.[38][39] The stone bears the Queen's royal cypher and has embedded in it a piece of stone from the ruins of St. Mary's Priory,[40] at Runnymede, England, where it is believed the Magna Carta was approved in 1215 by King John.[41]

Exhibition and facilities

[edit]On the fifth floor is the Carte International Reference Centre, the CMHR library "devoted to collecting and providing access to resources that support human rights learning and research."[42]

Exhibit design

[edit]The CMHR worked with exhibit designer Ralph Appelbaum Associates (RAA) from New York to develop the inaugural exhibits of the museum. RAA indicated that the galleries throughout the CMHR would deal with various themes including the Canadian human rights journey, Indigenous concepts of human rights, the Holocaust, and current human rights issues. The CMHR's team of researchers worked with RAA to develop the inaugural exhibits.

In January 2009, lawyer Yude Henteleff was appointed to chair the museum's content advisory committee, made up of human rights experts and leaders from across Canada. The committee was a key part of the museum's first large-scale public engagement exercise.[43] Through a cross-country tour from May 2009 to February 2010 called "Help Write the Story of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights",[44] CMHR researchers visited 19 cities and talked to thousands of people about their human rights experiences and what they wanted to see in the museum. This consultation process was led by Lord Cultural Resources, based in Toronto. On 5 March 2013, a story produced by CBC TV (Manitoba) mentioned a document, "Gallery Profiles" (dated 12 September 2012), that confirmed some of the CMHR's proposed contents. The museum's largest gallery is dedicated to Canadian content, while a thematic approach is taken throughout all of its galleries.

Galleries

[edit]The museum has had 10 core galleries since the time of its opening in September 2014:[32][45]

- What are human rights?

- Indigenous perspectives.

- This includes a "circular movie about First Nations concepts of rights and responsibilities to each other and the land."[46] Curator Lee-Ann Martin described contemporary installation artist Rebecca Belmore's "Trace",[45] a 2+1⁄2-storey "ceramic blanket" commissioned by the CMHR.[47] This blanket is part of a series by Winnipeg-based Anishinaabe artist Belmore that "expose the traumatic history and ongoing violence against Aboriginal people."[47]

- Canadian journeys.

- This includes "prominent exhibits" on residential schools, "missing and murdered aboriginal women", "forced relocation of Inuit".[48] as well as Japanese during World War II, disabilities from Ryerson University, Chinese head tax, the Underground Railroad, Komagata Maru and the Winnipeg General Strike.[46]

- Protecting rights in Canada

- Examining the Holocaust and other genocides.

- The gallery on genocide includes the five genocides recognized by Canada: the Holocaust, the Holodomor, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide and the Bosnian ethnic cleansing.[46]

- Turning points for humanity

- Breaking the silence

- Actions count

- Rights today

- Inspiring change

Indigenous issues are addressed in each gallery, but are prominent in the " Canadian Journeys Gallery" and the "Indigenous Perspectives Gallery".[48]

Partnerships

[edit]Several agreements have been reached by the CMHR and various educational institutions and government agencies, to enhance the quality and depth of information provided by the museum, as well as to broaden the educational opportunities for the museum. This is a tentative and evolving list of organizations that have partnered with the museum:

- University of Manitoba

- University of Winnipeg[49]

- National Museum – "Memorial to Holodomor victims" (Kyiv, Ukraine)[50]

- Canadian Association of Statutory Human Rights Agencies

- Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Canada (Netherlands Embassy)

- Library and Archives Canada

- The Manitoba Museum

- Manitoba Education (the Province of Manitoba)

Controversies

[edit]Location

[edit]The museum was criticized for its location in The Forks, an important Indigenous archaeological site. From 2008 to 2012, archaeological excavations on the museum site recovered more than 400,000 artifacts dating as far back as 1100 CE.[51] Retired archaeologist Leigh Syms stated that the excavation done prior to construction did not go far enough; a museum spokesperson stated that officials had consulted with Indigenous leaders and would continue to do so during construction.[52][53]

Furthermore, a report prepared for the Forks Renewal Corporation prior to the construction of the Forks Market in 1988 raised concerns about possible Indigenous burial grounds in the area. Several archaeological digs between 1989 and 1991, and then again in 2008 and 2009 by the CMHR, did not find any human remains.

Exhibits

[edit]Beginning in December 2010, controversy erupted over plans for two permanent galleries dedicated to the Holocaust and the mistreatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Several community organizations representing Canadians of Central and Eastern European descent, including the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, protested what they said was an over-emphasis on Jewish and Indigenous suffering, and the relegation of their experiences (such as the Holodomor) to smaller thematic or rotating galleries.[54][55][56][57]

Lubomyr Luciuk, speaking for the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, said that "as a publicly funded institution, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights should not elevate the suffering of any community above all others," referencing the Canadian internment of Ukrainians during World War I.[58][59] The UCCLA sent postcards to Heritage Minister James Moore, which were criticized by Catherine Chatterley of the Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism for depicting those in favour of the Holocaust gallery as pigs.[57][60][61] Ultimately, in July 2012, the CMHR agreed to collaborate with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv to provide further education to museum visitors about the Holodomor.[62][63]

Some Palestinian-Canadians were also upset by the fact that the CMHR did not include an exhibit featuring the Nakba due to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[64] "As the opening comes closer, I become more and more concerned that the lessons of the Palestinian experience, nobody's going to hear it," said Rana Abdulla. "Our story is an excellent story to educate Canadians about human rights. How would anyone take that museum seriously if they don't hear the Palestinian story?"[64] Mohamed El Rashidy of the Canadian Arab Federation said the museum had to address Palestinian experiences, and "shouldn't fear stating the inconvenient truths and facts about history."[64]

CMHR CEO Stuart Murray promised that the museum would be inclusive of all groups,[65] while museum spokesperson Angela Cassie responded that it was a "misconception" that there would only be two permanent galleries, and that the museum would reference several other historical genocides, including the Holodomor, in its "Mass Atrocity" section.[66][67][68] She further explained that the purpose of the museum was not to be a memorial for the suffering of different groups, but to be a learning experience; for instance, the Holocaust exhibit introduces the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was drafted in direct response to it.[69][70]

According to Canadian Jewish Congress CEO Bernie Farber, the events of the Holocaust merited particular focus precisely because they redefined the limits of "human depravity" and were "the foundation of our modern human rights legislation."[71] He also said that it "made sense" that another gallery be dedicated to Indigenous peoples, and criticized the "pitting of one group of Canadians against another."[68]

Winnipeg Free Press columnist Dan Lett similarly expressed dismay at the quarrel over the square footage allotted to any given atrocity or human rights violation, arguing that there should be less haggling over which wronged group gets the most space in a museum, and more concern over the prevention of human rights abuses in the future.[69] Scholars explored many of the controversies in The Idea of a Human Rights Museum.[72]

LGBT content censorship

[edit]From January 2015 until the middle of 2017 the management sometimes asked staff not to show any LGBT content on tours at the request of certain guests, including religious school groups, diplomats and donors. The communications department justified such requests by saying "all groups are special, some groups are just a bit more special and there are some things that shouldn't be put on paper. So we have to meet in person to discuss what guides can say to these special visitors."[73] In June 2020, CMHR CEO John Young resigned following complaints that staff were forced to censor LGBT content, as well as allegations of sexual harassment, homophobia and racism at the CMHR.[74] An apology from the Executive team of the CMHR and an interim report of the independent third-party review into allegations were published on the CMHR website, with Young and several others named as signatories to the apology.[75][76] In October 2020, it was revealed some staff were told not to talk about pregnancy or abortion, in addition to censoring LGBT content, during some tours involving religious schools.[77]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "SUMMARY OF THE 2018-2019 TO 2022-2023 CORPORATE PLAN AND THE 2018-2019 OPERATING AND CAPITAL BUDGETS" (PDF). Human Rights Canada. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Brean, Joseph (19 September 2014), "Canadian Museum for Human Rights opens amidst controversy and protests", National Post, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b "Info Source". CMHR. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Government of Canada 2008, p. 4.

- ^ "Prime Minister of Canada: Backgrounder: the Canadian Museum for Human Rights". 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "About Us". Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Israel Harold (Izzy) Asper". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. 14 March 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Gillian K; Davidson, Evelyn (2001). Who's Who in Canadian Business 2001. University of Toronto Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0920966608. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Canadian Museum for Human Rights – The Asper Foundation". Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ The Asper Family: A History of Giving, Asper Foundation, n.d., retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b c d e "Our History". CMHR. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b Lett, Dan (4 September 2010), "A portrait of the artist: The man who'll shape our skyline", Winnipeg Free Press, Winnipeg, Manitoba, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ "Government Bill (House of Commons) C-42 (39-2) – Royal Assent – An Act to amend the Museums Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts – Parliament of Canada". parl.ca. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Government of Canada 2008.

- ^ "Focus Group Testing of the Content for the Proposed Canadian Museum for Human Rights". Library and Archives Canada, 2 April 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Rabson, Mia (19 December 2008). "Dec 2008: Museum sod to be turned -- no matter how cold". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Building the Museum | Canadian Museum for Human Rights". 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Rights museum left in lurch. Winnipeg Free Press, 17 December 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Statement by the Honourable James Moore, Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages, on the Interim Chairperson of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Archived 20 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine CMHR News, 20 December 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- ^ Human rights museum a gong show. Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Winnipeg Sun, 19 December 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "City names street after Israel Asper". winnipegsun. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "A Tribe Called Red cancels performance at human rights museum". CBC News, 19 September 2014.

- ^ Canadian Museum for Human Rights opening marked by music, speeches and protests: Demonstrators call for attention to First Nations issues and the Palestinian struggle, CBC News, 19 September 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ "4. Financial Statements | Canadian Museum for Human Rights". 5 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ The Friends of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights Archived 31 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Update: Canadian Museum for Human Rights Archived 19 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (Craig, Colin). Canadian Taxpayers Federation, 10 November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Council grants more money to rights museum. CBC News, 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Human Rights Museum cost jumps to $351 million. Global News, 22 December 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ Loans ride to museum’s rescue. (Lett, Dan) Winnipeg Free Press, 19 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Canadian Museum of Human Rights". Winnipeg Architecture Foundation. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b Hume, Christopher (19 December 2009), "Soaring design tells human rights tale", Toronto Star

- ^ "Friends of CMHR 10 Year Magazine" (PDF), Friends of CMHR[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Canadian Museum For Human Rights". predock.com. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Canadian Museum for Human Rights | ALABASTER NEW CONCEPT". Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "UNIQUE ASPECTS OF CMHR CONSTRUCTION" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "About the Museum>News>The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is honoured to welcome Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada to the site of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights". Canadian Museum for Human Rights. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "About the Museum > News > Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II unveils cornerstone to CMHR". Canadian Museum for Human Rights. 2010. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Ruins of St. Mary's Priory – Runnymede. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Queen gives Canadian Museum for Human Rights a piece of history". CTV. 3 July 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Reference Centre". CMHR. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Canadian Museum for Human Rights annual report 2009-10" (PDF).

- ^ "Help Write the Story of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights".

- ^ a b Barnes, Dan (20 September 2014), "Inside the 10 permanent galleries of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights", Edmonton Journal, Winnipeg, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b c "Behind the scenes: curating Winnipeg's museum of human rights", Metro, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 20 September 2014, archived from the original on 23 October 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b Martin, Lee-Ann (12 March 2014), Rebecca Belmore's Trace: Hands of generations past and those that will come, CMHR, archived from the original on 7 October 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b Barnes, Dan (19 September 2014), "Human rights museum a journey into light", Edmonton Journal, Winnipeg, Manitoba, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Canadian Museum for Human Rights and the University of Winnipeg sign Memorandum of Understanding. CMHR News, 6 May 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ National Museum "Memorial in Commemoration of Famines` Victims in Ukraine" Archived 13 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ CMHR releases important archaeology findings: new light cast on historic role of The Forks, Winnipeg, Manitoba: CMHR, 28 August 2013, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Human Rights Museum mistreating First Nations heritage: archeologist Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rollason, Kevin (2 June 2009). "Jun 2009: Bless museum's sacred ground". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Canadian Museum for Human Rights – a call for inclusiveness, equity and fairness. Ukrainian Canadian Congress. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ German-Canadian group assails Holocaust exhibit. National Post, 17 December 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Protest grows over Holocaust 'zone' in Canadian Museum for Human Rights. (Adams, James). The Globe and Mail, 14 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ a b Chatterley, Catherine (2 April 2011). "The War Against the Holocaust". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Comparing genocides. National Post, 10 January 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund Archived 25 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. "CFWWIRF representatives visit Canadian Museum for Human Rights," 9 December 2014 – News Release.

- ^ Human rights museum plan irks Ukrainian group. CBC News, 5 January 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Postcard suggests Jews as pigs, critics say. The Canadian Jewish News, 14 April 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Canadian Museum for Human Rights establishes formal partnership with the Memorial in Commemoration of Famines’ Victims in Ukraine. Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine CMHR News, 4 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Memo on Holodomor fails to quell concern. Winnipeg Free Press, 10 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Hicks, Ryan (4 March 2013). "Palestinian-Canadians feel ignored in human rights museum". CBC News. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Rights museum will be inclusive. National Post, 17 January 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ "Ukrainian group wants review of human-rights museum plan." Globe and Mail, 21 December 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Definition: What are Mass Atrocities? Archived 29 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine AEGIS – Preventing Crimes Against Humanity. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b Ukrainian groups oppose museum’s Holocaust exhibit. The Canadian Jewish News, 20 January 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ a b Lett, Dan (14 December 2010). "Fighting over exhibit size no way to advance debate". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Martin, Melissa (6 January 2011). "Holodomor drive intensifies – Rights museum lobbied on issue". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ This refers to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was in part a response to the atrocities of World War II.

- ^ Busby, Karen (2015). The Idea of a Human Rights Museum. University of Manitoba Press.

- ^ Grabish, Austin. "Canadian Museum for Human Rights employees say they were told to censor gay content for certain guests | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Grabish, Austin. "Museum for Human Rights CEO resigns after LGBT censorship, allegations of racism, harassment | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Apology from the Executive team of the CMHR". CMHR. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "CMHR releases independent report". CMHR. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Grabish, Austin. "Canadian Museum for Human Rights staff told not to mention abortion during some tours: email | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

References

[edit]- Bill C-42: An Act to amend the Museums Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts (PDF), Library of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario: Government of Canada, 22 February 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

External links

[edit]- Canadian federal Crown corporations

- Museums in Winnipeg

- National museums of Canada

- Human rights organizations based in Canada

- Antoine Predock buildings

- Human rights museums

- Museums established in 2008

- Museums established in 2014

- 2008 establishments in Manitoba

- 2014 establishments in Manitoba

- Tourist attractions in Winnipeg

- Federal government buildings in Manitoba