CoRoT-2

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Aquila |

| Right ascension | 19h 27m 06.4944s[1] |

| Declination | +01° 23′ 01.360″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 12.57[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G7V[3] K0V (SIMBAD)[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | ~12.577 |

| Apparent magnitude (I) | 11.49 ±0.03 |

| Apparent magnitude (J) | 10.5783 ±0.028 |

| Apparent magnitude (H) | 10.44 ±0.04 |

| Apparent magnitude (K) | 10.31 ±0.03 |

| Astrometry | |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3.360(16) mas/yr[1] Dec.: −11.101(12) mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 4.6895 ± 0.0143 mas[1] |

| Distance | 696 ± 2 ly (213.2 ± 0.7 pc) |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.97 ±0.06 M☉ |

| Radius | 0.902 ±0.018 R☉ |

| Temperature | 5625 ±120 K |

| Metallicity | 0 ±0.1 |

| Age | ? years |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

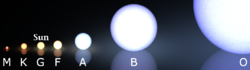

CoRoT-2 is a yellow dwarf main sequence star a little cooler than the Sun. This star is located approximately 700 light-years away in the constellation of Aquila. The apparent magnitude of this star is 12, which means it is not visible to the naked eye but can be seen with a medium-sized amateur telescope on a clear dark night.[2]

It has a true physical companion, 2MASS J19270636+0122577, with a spectral type of K9, as earlier hypothesized by Alonso et al. (2008), making CoRoT-2 a wide binary system with at least one planet.[4]

Planetary system

[edit]This star is home to exoplanet CoRoT-2b discovered by the CoRoT Mission spacecraft using the transit method.[3] CoRoT-2b (formerly known as CoRoT-Exo-2b[5]) is the second extrasolar planet to be detected by the French-led CoRoT mission, and orbits the star CoRoT-2 at a distance of 930 light years from Earth towards the constellation Aquila. Its discovery was announced on 20 December 2007.[6] After its discovery via the transit method, its mass was confirmed via the radial velocity method.

The planet is a large hot Jupiter, about 1.43 times the radius of Jupiter and approximately 3.3 times as massive. Its huge size is due to the intense heating from its parent star, which causes the outer layers of its atmosphere to bloat. The extremely large radius of the planet indicates that CoRoT-2b is really hot, estimated to be around 1500 K, even hotter than would be expected given its location close to its parent star. This fact may be a sign of tidal heating due to interactions with another planet.[7] At Jupiter-like distances its radius would roughly be the same as Jupiter.[8] The complete phase curve of this planet has been observed.[9]

CoRoT-2b orbits its star approximately once every 1.7 days, and orbits the star in a prograde direction close to the star's equator.[10] Its parent star is a G-type star, a bit cooler than the Sun but more active. It is located about 800 light-years from Earth.

It takes 125 minutes to transit its star.[11]

As of August 2008, the CoRoT-2b spin-orbit angle (that is, the angle between the equator of the star and the plane of the planet orbit) was calculated by Bouchy et al. by means of the Rossiter–McLaughlin effect[12] with a value of +7.2 ± 4.5 degrees.[10]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 3.31±0.16 MJ | 0.0281±0.0009 | 1.74299705(15) d[13] | 0 | — | 1.429±0.047 RJ |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d "GSC 00465-01282". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ a b Alonso, R.; et al. (2008). "Transiting exoplanets from the CoRoT space mission. II. CoRoT-Exo-2b: a transiting planet around an active G star". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 482 (3): L21 – L24. arXiv:0803.3207. Bibcode:2008A&A...482L..21A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809431. S2CID 14288300.

- ^ S. Czesla; S. Schröter; U. Wolter; C. von Essen; K. F. Huber; J. H. M. M. Schmitt; D. E. Reichart; J. P. Moore (March 2012). "The extended chromosphere of CoRoT-2A: Discovery and analysis of the chromospheric Rossiter-McLaughlin effect". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 539: A150. Bibcode:2012A&A...539A.150C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118042.

- ^ Schneider, J. (10 March 2009). "Change in CoRoT planets names". Exoplanets (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "COROT surprises a year after launch". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ "CoRoT-exo-2 c?". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Gibor Basri; Brown (20 August 2006). "Planetesimals to Brown Dwarfs: What is a Planet?". Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 34: 193–216. arXiv:astro-ph/0608417. Bibcode:2006AREPS..34..193B. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.34.031405.125058. S2CID 119338327.

- ^ Cowan, Nicolas; Deming, Drake; Gillon, Michael; Knutson, Heather; Madhusudhan, Nikku; Rauscher, Emily (2011). "Phase Variations, Transits and Eclipses of the Misfit CoRoT-2b". Spitzer Proposal: 80044. Bibcode:2011sptz.prop80044C.

- ^ a b Bouchy, F.; Queloz, D.; Deleuil, M.; Loeillet, B.; Hatzes, A. P.; Aigrain, S.; Alonso, R.; Auvergne, M.; Baglin, A.; Barge, P.; Benz, W.; Bordé, P.; Deeg, H. J.; De La Reza, R.; Dvorak, R.; Erikson, A.; Fridlund, M.; Gondoin, P.; Guillot, T.; Hébrard, G.; Jorda, L.; Lammer, H.; Léger, A.; Llebaria, A.; Magain, P.; Mayor, M.; Moutou, C.; Ollivier, M.; Pätzold, M.; et al. (2008). "Transiting exoplanets from the CoRoT space mission". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 482 (3): L25. arXiv:0803.3209. Bibcode:2008A&A...482L..25B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809433. S2CID 15766192.

- ^ "Predicted Transit Epochs: CoRoTExo2 b". TransitSearch (Oklo Corporation). Retrieved 2009-07-15.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Joshua N. Winn (2008). "Measuring accurate transit parameters". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 4: 99–109. arXiv:0807.4929. Bibcode:2009IAUS..253...99W. doi:10.1017/S174392130802629X. S2CID 34144676.

- ^ Kokori, A.; et al. (14 February 2023). "ExoClock Project. III. 450 New Exoplanet Ephemerides from Ground and Space Observations". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 265 (1) 4. arXiv:2209.09673. Bibcode:2023ApJS..265....4K. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ac9da4. Vizier catalog entry

External links

[edit]- "CoRot-2". Exoplanets. Archived from the original on 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2009-04-28.