Sirolimus

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Rapamune, Fyarro, Hyftor |

| Other names | Rapamycin, ABI-009 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 14% (oral solution), lower with high-fat meals; 18% (tablet), higher with high-fat meals[7] |

| Protein binding | 92% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 57–63 hours[8] |

| Excretion | Mostly fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.107.147 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C51H79NO13 |

| Molar mass | 914.187 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | 0.0026 [9] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Sirolimus, also known as rapamycin and sold under the brand name Rapamune among others, is a macrolide compound that is used to coat coronary stents, prevent organ transplant rejection, treat a rare lung disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and treat perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa).[2][3][10][11] It has immunosuppressant functions in humans and is especially useful in preventing the rejection of kidney transplants. It is a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase inhibitor[3] that reduces the sensitivity of T cells and B cells to interleukin-2 (IL-2), inhibiting their activity.[12]

This compound also has a use in cardiovascular drug-eluting stent technologies to inhibit restenosis.

It is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus and was isolated for the first time in 1972, from samples of Streptomyces hygroscopicus found on Easter Island.[13][14][15] The compound was originally named rapamycin after the native name of the island, Rapa Nui.[10] Sirolimus was initially developed as an antifungal agent. However, this use was abandoned when it was discovered to have potent immunosuppressive and antiproliferative properties due to its ability to inhibit mTOR. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999.[16] Hyftor (sirolimus gel) was approved for topical treatment of facial angiofibroma in the European Union in May 2023.[6]

Medical uses

[edit]Sirolimus is indicated for the prevention of organ transplant rejection and for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).[2]

Sirolimus (Fyarro), as protein-bound particles, is indicated for the treatment of adults with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa).[3][17]

In the EU, sirolimus, as Rapamune, is indicated for the prophylaxis of organ rejection in adults at low to moderate immunological risk receiving a renal transplant[5] and, as Hyftor, is indicated for the treatment of facial angiofibroma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.[6]

Prevention of transplant rejection

[edit]The chief advantage sirolimus has over calcineurin inhibitors is its low toxicity toward kidneys. Transplant patients maintained on calcineurin inhibitors long-term tend to develop impaired kidney function or even kidney failure; this can be avoided by using sirolimus instead. It is particularly advantageous in patients with kidney transplants for hemolytic-uremic syndrome, as this disease is likely to recur in the transplanted kidney if a calcineurin-inhibitor is used. However, on 7 October 2008, the FDA approved safety labeling revisions for sirolimus to warn of the risk for decreased renal function associated with its use.[18][19] In 2009, the FDA notified healthcare professionals that a clinical trial conducted by Wyeth showed an increased mortality in stable liver transplant patients after switching from a calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppressive regimen to sirolimus.[20] A 2019 cohort study of nearly 10,000 lung transplant recipients in the US demonstrated significantly improved long-term survival using sirolimus + tacrolimus instead of mycophenolate mofetil + tacrolimus for immunosuppressive therapy starting at one year after transplant.[21]

Sirolimus can also be used alone, or in conjunction with a calcineurin inhibitor (such as tacrolimus), and/or mycophenolate mofetil, to provide steroid-free immunosuppression regimens. Impaired wound healing and thrombocytopenia are possible side effects of sirolimus; therefore, some transplant centers prefer not to use it immediately after the transplant operation, but instead administer it only after a period of weeks or months. Its optimal role in immunosuppression has not yet been determined, and it remains the subject of a number of ongoing clinical trials.[12]

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

[edit]In May 2015, the FDA approved sirolimus to treat lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a rare, progressive lung disease that primarily affects women of childbearing age. This made sirolimus the first drug approved to treat this disease.[22] LAM involves lung tissue infiltration with smooth muscle-like cells with mutations of the tuberous sclerosis complex gene (TSC2). Loss of TSC2 gene function activates the mTOR signaling pathway, resulting in the release of lymphangiogenic growth factors. Sirolimus blocks this pathway.[2]

The safety and efficacy of sirolimus treatment of LAM were investigated in clinical trials that compared sirolimus treatment with a placebo group in 89 patients for 12 months. The patients were observed for 12 months after the treatment had ended. The most commonly reported side effects of sirolimus treatment of LAM were mouth and lip ulcers, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, sore throat, acne, chest pain, leg swelling, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, dizziness, muscle pain and elevated cholesterol. Serious side effects including hypersensitivity and swelling (edema) have been observed in renal transplant patients.[22]

While sirolimus was considered for treatment of LAM, it received orphan drug designation status because LAM is a rare condition.[22]

The safety of LAM treatment by sirolimus in people younger than 18 years old has not been tested.[2]

Coronary stent coating

[edit]The antiproliferative effect of sirolimus has also been used in conjunction with coronary stents to prevent restenosis in coronary arteries following balloon angioplasty. The sirolimus is formulated in a polymer coating that affords controlled release through the healing period following coronary intervention. Several large clinical studies have demonstrated lower restenosis rates in patients treated with sirolimus-eluting stents when compared to bare-metal stents, resulting in fewer repeat procedures. A sirolimus-eluting coronary stent was marketed by Cordis, a division of Johnson & Johnson, under the tradename Cypher.[11] However, this kind of stent may also increase the risk of vascular thrombosis.[23]

Vascular malformations

[edit]Sirolimus is used to treat vascular malformations. Treatment with sirolimus can decrease pain and the fullness of vascular malformations, improve coagulation levels, and slow the growth of abnormal lymphatic vessels.[24] Sirolimus is a relatively new medical therapy for the treatment of vascular malformations[25] in recent years, sirolimus has emerged as a new medical treatment option for both vascular tumors and vascular malformations, as a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), capable of integrating signals from the PI3K/AKT pathway to coordinate proper cell growth and proliferation. Hence, sirolimus is ideal for "proliferative" vascular tumors through the control of tissue overgrowth disorders caused by inappropriate activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as an antiproliferative agent.[26][27]

Angiofibromas

[edit]Sirolimus has been used as a topical treatment of angiofibromas with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Facial angiofibromas occur in 80% of patients with TSC, and the condition is very disfiguring. A retrospective review of English-language medical publications reporting on topical sirolimus treatment of facial angiofibromas found sixteen separate studies with positive patient outcomes after using the drug. The reports involved a total of 84 patients, and improvement was observed in 94% of subjects, especially if treatment began during the early stages of the disease. Sirolimus treatment was applied in several different formulations (ointment, gel, solution, and cream), ranging from 0.003 to 1% concentrations. Reported adverse effects included one case of perioral dermatitis, one case of cephalea, and four cases of irritation.[28]

In April 2022, sirolimus was approved by the FDA for treating angiofibromas.[29]

Adverse effects

[edit]The most common adverse reactions (≥30% occurrence, leading to a 5% treatment discontinuation rate) observed with sirolimus in clinical studies of organ rejection prophylaxis in individuals with kidney transplants include: peripheral edema, hypercholesterolemia, abdominal pain, headache, nausea, diarrhea, pain, constipation, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, increased creatinine, fever, urinary tract infection, anemia, arthralgia, and thrombocytopenia.[2]

The most common adverse reactions (≥20% occurrence, leading to an 11% treatment discontinuation rate) observed with sirolimus in clinical studies for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis are: peripheral edema, hypercholesterolemia, abdominal pain, headache, nausea, diarrhea, chest pain, stomatitis, nasopharyngitis, acne, upper respiratory tract infection, dizziness, and myalgia.[2]

The following adverse effects occurred in 3–20% of individuals taking sirolimus for organ rejection prophylaxis following a kidney transplant:[2]

| System | Adverse effects |

|---|---|

| Body as a whole | Sepsis, lymphocele, herpes zoster infection, herpes simplex infection |

| Cardiovascular | Venous thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis), rapid heart rate |

| Digestive | Stomatitis |

| Hematologic/lymphatic | Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/HUS), leukopenia |

| Metabolic | Abnormal healing, increased lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), hypokalemia, diabetes |

| Musculoskeletal | Bone necrosis |

| Respiratory | Pneumonia, epistaxis |

| Skin | Melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma |

| Urogenital | Pyelonephritis, ovarian cysts, menstrual disorders (amenorrhea and menorrhagia) |

Diabetes-like symptoms

[edit]While sirolimus inhibition of mTORC1 appears to mediate the drug's benefits, it also inhibits mTORC2, which results in diabetes-like symptoms.[30] This includes decreased glucose tolerance and insensitivity to insulin.[30] Sirolimus treatment may additionally increase the risk of type 2 diabetes.[31] In mouse studies, these symptoms can be avoided through the use of alternate dosing regimens or analogs such as everolimus or temsirolimus.[32]

Lung toxicity

[edit]Lung toxicity is a serious complication associated with sirolimus therapy,[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][excessive citations] especially in the case of lung transplants.[40] The mechanism of the interstitial pneumonitis caused by sirolimus and other macrolide MTOR inhibitors is unclear, and may have nothing to do with the mTOR pathway.[41][42][43] The interstitial pneumonitis is not dose-dependent, but is more common in patients with underlying lung disease.[33][44]

Lowered effectiveness of immune system

[edit]There have been warnings about the use of sirolimus in transplants, where it may increase mortality due to an increased risk of infections.[2]

Cancer risk

[edit]Sirolimus may increase an individual's risk for contracting skin cancers from exposure to sunlight or UV radiation, and risk of developing lymphoma.[2] In studies, the skin cancer risk under sirolimus was lower than under other immunosuppressants such as azathioprine and calcineurin inhibitors, and lower than under placebo.[2][45]

Impaired wound healing

[edit]Individuals taking sirolimus are at increased risk of experiencing impaired or delayed wound healing, particularly if they have a body mass index in excess of 30 kg/m2 (classified as obese).[2]

Interactions

[edit]Sirolimus is metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme and is a substrate of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump; hence, inhibitors of either protein may increase sirolimus concentrations in blood plasma, whereas inducers of CYP3A4 and P-gp may decrease sirolimus concentrations in blood plasma.[2]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Unlike the similarly named tacrolimus, sirolimus is not a calcineurin inhibitor, but it has a similar suppressive effect on the immune system. Sirolimus inhibits IL-2 and other cytokine receptor-dependent signal transduction mechanisms, via action on mTOR, and thereby blocks activation of T and B cells. Ciclosporin and tacrolimus inhibit the secretion of IL-2, by inhibiting calcineurin.[12]

The mode of action of sirolimus is to bind the cytosolic protein FK-binding protein 12 (FKBP12) in a manner similar to tacrolimus. Unlike the tacrolimus-FKBP12 complex, which inhibits calcineurin (PP2B), the sirolimus-FKBP12 complex inhibits the mTOR (mammalian Target Of Rapamycin, rapamycin being another name for sirolimus) pathway by directly binding to mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1).[12]

mTOR has also been called FRAP (FKBP-rapamycin-associated protein), RAFT (rapamycin and FKBP target), RAPT1, or SEP. The earlier names FRAP and RAFT were coined to reflect the fact that sirolimus must bind FKBP12 first, and only the FKBP12-sirolimus complex can bind mTOR. However, mTOR is now the widely accepted name, since Tor was first discovered via genetic and molecular studies of sirolimus-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that identified FKBP12, Tor1, and Tor2 as the targets of sirolimus and provided robust support that the FKBP12-sirolimus complex binds to and inhibits Tor1 and Tor2.[46][12]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Sirolimus is metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme and is a substrate of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump.[2] It has linear pharmacokinetics.[47] In studies on N=6 and N=36 subjects, peak concentration was obtained in 1.3 hours +/r- 0.5 hours and the terminal elimination was slow, with a half life around 60 hours +/- 10 hours.[48][47] Sirolimus was not found to effect the concentration of ciclosporin, which is also metabolized primarily by the CYP3A4 enzyme.[47]

The bioavailabiliy of sirolimus is low, and the absorption of sirolimus into the blood stream from the intestine varies widely between patients, with some patients having up to eight times more exposure than others for the same dose. Drug levels are, therefore, taken to make sure patients get the right dose for their condition.[12][non-primary source needed] This is determined by taking a blood sample before the next dose, which gives the trough level. However, good correlation is noted between trough concentration levels and drug exposure, known as area under the concentration-time curve, for both sirolimus (SRL) and tacrolimus (TAC) (SRL: r2 = 0.83; TAC: r2 = 0.82), so only one level need be taken to know its pharmacokinetic (PK) profile. PK profiles of SRL and of TAC are unaltered by simultaneous administration. Dose-corrected drug exposure of TAC correlates with SRL (r2 = 0.8), so patients have similar bioavailability of both.[49][non-primary source needed]

Chemistry

[edit]This section needs expansion with: content on this topic from [8]. You can help by adding to it. (August 2016) |

Sirolimus is a natural product and macrocyclic lactone.[8]

Biosynthesis

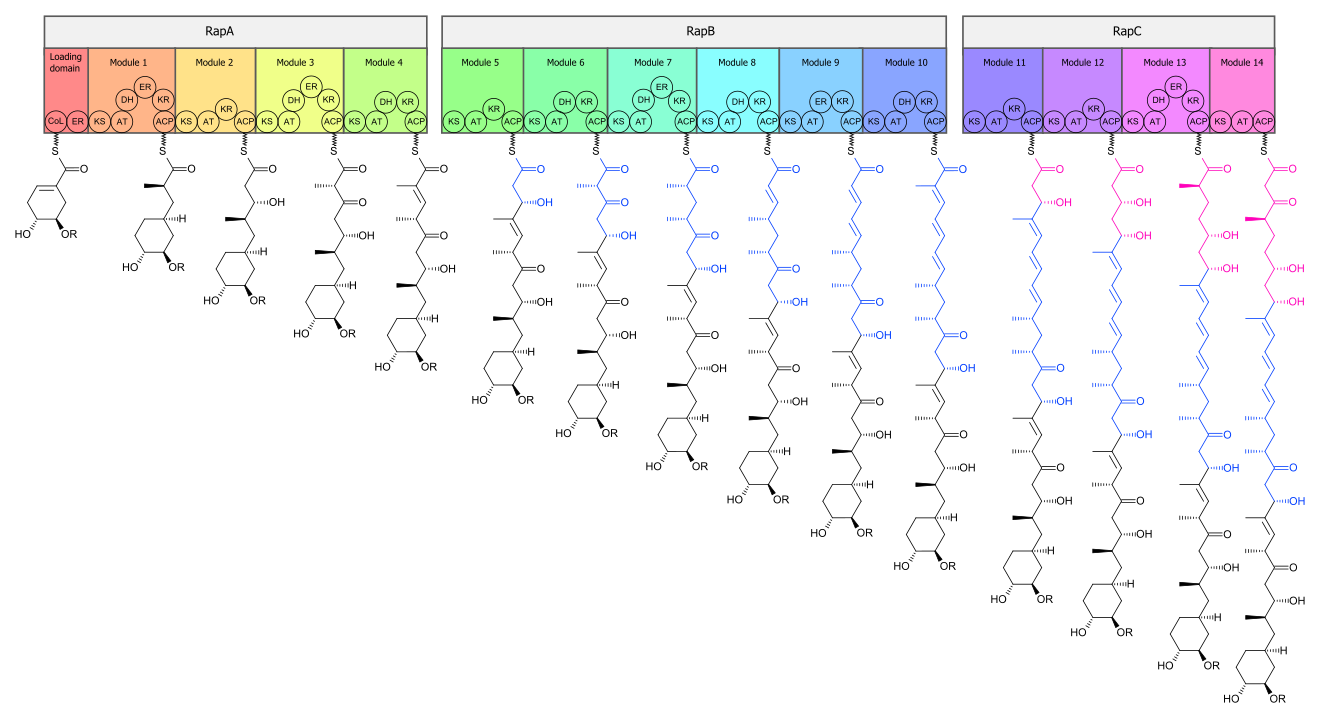

[edit]The biosynthesis of the rapamycin core is accomplished by a type I polyketide synthase (PKS) in conjunction with a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS). The domains responsible for the biosynthesis of the linear polyketide of rapamycin are organized into three multienzymes, RapA, RapB, and RapC, which contain a total of 14 modules (figure 1). The three multienzymes are organized such that the first four modules of polyketide chain elongation are in RapA, the following six modules for continued elongation are in RapB, and the final four modules to complete the biosynthesis of the linear polyketide are in RapC.[50] Then, the linear polyketide is modified by the NRPS, RapP, which attaches L-pipecolate to the terminal end of the polyketide, and then cyclizes the molecule, yielding the unbound product, prerapamycin.[51]

The core macrocycle, prerapamycin (figure 2), is then modified (figure 3) by an additional five enzymes, which lead to the final product, rapamycin. First, the core macrocycle is modified by RapI, SAM-dependent O-methyltransferase (MTase), which O-methylates at C39. Next, a carbonyl is installed at C9 by RapJ, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (P-450). Then, RapM, another MTase, O-methylates at C16. Finally, RapN, another P-450, installs a hydroxyl at C27 immediately followed by O-methylation by Rap Q, a distinct MTase, at C27 to yield rapamycin.[52]

The biosynthetic genes responsible for rapamycin synthesis have been identified. As expected, three extremely large open reading frames (ORF's) designated as rapA, rapB, and rapC encode for three extremely large and complex multienzymes, RapA, RapB, and RapC, respectively.[50] The gene rapL has been established to code for a NAD+-dependent lysine cycloamidase, which converts L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid (figure 4) for incorporation at the end of the polyketide.[53][54] The gene rapP, which is embedded between the PKS genes and translationally coupled to rapC, encodes for an additional enzyme, an NPRS responsible for incorporating L-pipecolic acid, chain termination and cyclization of prerapamycin. In addition, genes rapI, rapJ, rapM, rapN, rapO, and rapQ have been identified as coding for tailoring enzymes that modify the macrocyclic core to give rapamycin (figure 3). Finally, rapG and rapH have been identified to code for enzymes that have a positive regulatory role in the preparation of rapamycin through the control of rapamycin PKS gene expression.[55] Biosynthesis of this 31-membered macrocycle begins as the loading domain is primed with the starter unit, 4,5-dihydroxocyclohex-1-ene-carboxylic acid, which is derived from the shikimate pathway.[50] Note that the cyclohexane ring of the starting unit is reduced during the transfer to module 1. The starting unit is then modified by a series of Claisen condensations with malonyl or methylmalonyl substrates, which are attached to an acyl carrier protein (ACP) and extend the polyketide by two carbons each. After each successive condensation, the growing polyketide is further modified according to enzymatic domains that are present to reduce and dehydrate it, thereby introducing the diversity of functionalities observed in rapamycin (figure 1). Once the linear polyketide is complete, L-pipecolic acid, which is synthesized by a lysine cycloamidase from an L-lysine, is added to the terminal end of the polyketide by an NRPS. Then, the NSPS cyclizes the polyketide, giving prerapamycin, the first enzyme-free product. The macrocyclic core is then customized by a series of post-PKS enzymes through methylations by MTases and oxidations by P-450s to yield rapamycin.

Research

[edit]

Cancer

[edit]The antiproliferative effects of sirolimus may have a role in treating cancer. When dosed appropriately, sirolimus can enhance the immune response to tumor targeting[56] or otherwise promote tumor regression in clinical trials.[57] Sirolimus seems to lower the cancer risk in some transplant patients.[58]

Sirolimus was shown to inhibit the progression of dermal Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with renal transplants.[59] Other mTOR inhibitors, such as temsirolimus (CCI-779) or everolimus (RAD001), are being tested for use in cancers such as glioblastoma multiforme and mantle cell lymphoma. However, these drugs have a higher rate of fatal adverse events in cancer patients than control drugs.[60]

A combination therapy of doxorubicin and sirolimus has been shown to drive Akt-positive lymphomas into remission in mice. Akt signalling promotes cell survival in Akt-positive lymphomas and acts to prevent the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy drugs, such as doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide. Sirolimus blocks Akt signalling and the cells lose their resistance to the chemotherapy. Bcl-2-positive lymphomas were completely resistant to the therapy; eIF4E-expressing lymphomas are not sensitive to sirolimus.[61][62][63][64][65]

Tuberous sclerosis complex

[edit]Sirolimus also shows promise in treating tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), a congenital disorder that predisposes those afflicted to benign tumor growth in the brain, heart, kidneys, skin, and other organs. After several studies conclusively linked mTOR inhibitors to remission in TSC tumors, specifically subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in children and angiomyolipomas in adults, many US doctors began prescribing sirolimus (Wyeth's Rapamune) and everolimus (Novartis's RAD001) to TSC patients off-label. Numerous clinical trials using both rapamycin analogs, involving both children and adults with TSC, are underway in the United States.[66]

Effects on longevity

[edit]mTOR, specifically mTORC1, was first shown to be important in aging in 2003, in a study on worms; sirolimus was shown to inhibit and slow aging in worms, yeast, and flies, and then to improve the condition of mouse models of various diseases of aging.[67][68] Sirolimus was first shown to extend lifespan in wild-type mice in a study published by NIH investigators in 2009; the studies have been replicated in mice of many different genetic backgrounds.[68] A study published in 2020 found late-life sirolimus dosing schedules enhanced mouse lifespan in a sex-specific manner: limited rapamycin exposure enhanced male but not female lifespan, providing evidence for sex differences in sirolimus response.[69][70] The results are further supported by the finding that genetically modified mice with impaired mTORC1 signalling live longer.[68]

Sirolimus has potential for widespread use as a longevity-promoting drug, with evidence pointing to its ability to prevent age-associated decline of cognitive and physical health. In 2014, researchers at Novartis showed that a related compound, everolimus, increased elderly patients' immune response on an intermittent dose.[71] This led to many in the anti-aging community self-experimenting with the compound.[72] However, because of the different biochemical properties of sirolimus, the dosing is potentially very different from that of everolimus. Ultimately, due to known side-effects of sirolimus, as well as inadequate evidence for optimal dosing, it was concluded in 2016 that more research was required before sirolimus could be widely prescribed for this purpose.[68][73] Two human studies on the effects of sirolimus (rapamycin) on longevity did not show statistically significant benefits. However, due to limitations in the studies, further research is needed to fully assess its potential in humans.[74]

Sirolimus has complex effects on the immune system—while IL-12 goes up and IL-10 decreases, which suggests an immunostimulatory response, TNF and IL-6 are decreased, which suggests an immunosuppressive response. The duration of the inhibition and the exact extent to which mTORC1 and mTORC2 are inhibited play a role, but were not yet well understood according to a 2015 paper.[75]

Topical administration

[edit]When applied as a topical preparation, researchers showed that rapamycin can regenerate collagen and reverse clinical signs of aging in elderly patients.[76] The concentrations are far lower than those used to treat angiofibromas.[citation needed]

SARS-CoV-2

[edit]Rapamycin has been proposed as a treatment for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 insofar as its immunosuppressive effects could prevent or reduce the cytokine storm seen in very serious cases of COVID-19.[77] Moreover, inhibition of cell proliferation by rapamycin could reduce viral replication.[77]

Atherosclerosis

[edit]Rapamycin can accelerate degradation of oxidized LDL cholesterol in endothelial cells, thereby lowering the risk of atherosclerosis.[78] Oxidized LDL cholesterol is a major contributor to atherosclerosis.[79]

Lupus

[edit]As of 2016, studies in cells, animals, and humans have suggested that mTOR activation as process underlying systemic lupus erythematosus and that inhibiting mTOR with rapamycin may be a disease-modifying treatment.[80] As of 2016 rapamycin had been tested in small clinical trials in people with lupus.[80]

Lymphatic malformation (LM)

[edit]Lymphatic malformation, lymphangioma or cystic hygroma, is an abnormal growth of lymphatic vessels that usually affects children around the head and neck area and more rarely involving the tongue causing macroglossia. LM is caused by a PIK3CA mutation during lymphangiogenesis early in gestational cell formation causing the malformation of lymphatic tissue. Treatment often consists of removal of the affected tissue via excision, laser ablation or sclerotherapy, but the rate of recurrence can be high and surgery can have complications. Sirolimus has shown evidence of being an effective treatment in alleviating symptoms and reducing the size of the malformation by way of altering the mTOR pathway in lymphangiogenesis. Although an off label use of the drug, Sirolimus has been shown to be an effective treatment for both microcystic and macrocystic LM. More research is however needed to develop and create targeted, effective treatment therapies for LM.[81]

Graft-versus-host disease

[edit]Due to its immunosuppressant activity, Rapamycin has been assessed as prophylaxis or treatment agent of Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. While contrasted results were obtained in clinical trials,[82] pre-clinical studies have shown that Rapamycin can mitigate GVHD by increasing the proliferation of regulatory T cells, inhibiting cytotoxic T cells and lowering the differentiation of effector T cells.[83][84]

Applications in biology research

[edit]Rapamycin is used in biology research as an agent for chemically induced dimerization.[85] In this application, rapamycin is added to cells expressing two fusion constructs, one of which contains the rapamycin-binding FRB domain from mTOR and the other of which contains an FKBP domain. Each fusion protein also contains additional domains that are brought into proximity when rapamycin induces binding of FRB and FKBP. In this way, rapamycin can be used to control and study protein localization and interactions.[citation needed]

Veterinary uses

[edit]A number of veterinary medicine teaching hospitals are participating in a long-term clinical study examining the effect of rapamycin on the longevity of dogs.[86]

References

[edit]- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Rapamune- sirolimus solution Rapamune- sirolimus tablet, sugar coated". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Fyarro- sirolimus injection, powder, lyophilized, for suspension". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Hyftor- sirolimus gel". DailyMed. 28 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Rapamune EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Hyftor EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 9 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Buck ML (2006). "Immunosuppression With Sirolimus After Solid Organ Transplantation in Children". Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. 12 (2). Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Rapamycin". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Simamora P, Alvarez JM, Yalkowsky SH (February 2001). "Solubilization of rapamycin". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 213 (1–2): 25–29. doi:10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00617-7. PMID 11165091.

- ^ a b Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN (October 1975). "Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle". The Journal of Antibiotics. 28 (10): 721–726. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.28.721. PMID 1102508.

- ^ a b "Cypher Sirolimus-eluting Coronary Stent". Cypher Stent. Archived from the original on 27 April 2003. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Mukherjee S, Mukherjee U (1 January 2009). "A comprehensive review of immunosuppression used for liver transplantation". Journal of Transplantation. 2009: 701464. doi:10.1155/2009/701464. PMC 2809333. PMID 20130772.

- ^ Qari S, Walters P, Lechtenberg S (21 May 2021). "The Dirty Drug and the Ice Cream Tub". Radiolab. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Seto B (November 2012). "Rapamycin and mTOR: a serendipitous discovery and implications for breast cancer". Clinical and Translational Medicine. 1 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/2001-1326-1-29. PMC 3561035. PMID 23369283.

- ^ Pritchard DI (May 2005). "Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens". Drug Discovery Today. 10 (10): 688–691. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7. PMID 15896681.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Rapamune (Sirolimus)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 March 2001. NDA 021083. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022.

(From Medical Reviews Part 1) Rapamycin (sirolimus) Oral Solution should be approved for the indication of prophylaxis of organ rejection in patients receiving allogenic renal transplants, to be used concomitantly with cyclosporine and corticosteroids.

- ^ "Aadi Bioscience Announces FDA Approval of its First Product Fyarro for Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Malignant Perivascular etc Epithelioid Cell Tumor (PEComa)". Aadi Bioscience, Inc. (Press release). 23 November 2021. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Li JJ, Corey EJ (3 April 2013). Drug Discovery: Practices, Processes, and Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35446-9. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Koprowski G (7 February 2012). Nanotechnology in Medicine: Emerging Applications. Momentum Press. ISBN 978-1-60650-250-1. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Sirolimus (marketed as Rapamune) Safety". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Wijesinha M, Hirshon JM, Terrin M, Magder L, Brown C, Stafford K, et al. (August 2019). "Survival Associated With Sirolimus Plus Tacrolimus Maintenance Without Induction Therapy Compared With Standard Immunosuppression After Lung Transplant". JAMA Network Open. 2 (8): e1910297. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10297. PMC 6716294. PMID 31461151.

- ^ a b c Pahon E (28 May 2015). "FDA approves Rapamune to treat LAM, a very rare lung disease". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Shuchman M (November 2006). "Trading restenosis for thrombosis? New questions about drug-eluting stents". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (19): 1949–1952. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068234. PMID 17093244.

- ^ "Venous Malformation: Treatments". Boston Children's Hospital. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Dekeuleneer V, Seront E, Van Damme A, Boon LM, Vikkula M (April 2020). "Theranostic Advances in Vascular Malformations". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 140 (4): 756–763. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.10.001. PMID 32200879.

- ^ Lee BB (January 2020). "Sirolimus in the treatment of vascular anomalies". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 71 (1): 328. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.246. PMID 31864650.

- ^ Triana P, Dore M, Cerezo VN, Cervantes M, Sánchez AV, Ferrero MM, et al. (February 2017). "Sirolimus in the Treatment of Vascular Anomalies". European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 27 (1): 86–90. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593383. PMID 27723921.

- ^ Balestri R, Neri I, Patrizi A, Angileri L, Ricci L, Magnano M (January 2015). "Analysis of current data on the use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 29 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1111/jdv.12665. PMID 25174683. S2CID 9967001.

- ^ "FDA Approves Nobelpharma's Topical Treatment for Facial Angiofibroma". FDAnews. 7 April 2022. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM, et al. (March 2012). "Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity". Science. 335 (6076): 1638–1643. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1638L. doi:10.1126/science.1215135. PMC 3324089. PMID 22461615.

- ^ Johnston O, Rose CL, Webster AC, Gill JS (July 2008). "Sirolimus is associated with new-onset diabetes in kidney transplant recipients". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 19 (7): 1411–1418. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007111202. PMC 2440303. PMID 18385422.

- ^ Arriola Apelo SI, Neuman JC, Baar EL, Syed FA, Cummings NE, Brar HK, et al. (February 2016). "Alternative rapamycin treatment regimens mitigate the impact of rapamycin on glucose homeostasis and the immune system". Aging Cell. 15 (1): 28–38. doi:10.1111/acel.12405. PMC 4717280. PMID 26463117.

- ^ a b Chhajed PN, Dickenmann M, Bubendorf L, Mayr M, Steiger J, Tamm M (2006). "Patterns of pulmonary complications associated with sirolimus". Respiration; International Review of Thoracic Diseases. 73 (3): 367–374. doi:10.1159/000087945. PMID 16127266. S2CID 24408680.

- ^ Morelon E, Stern M, Israël-Biet D, Correas JM, Danel C, Mamzer-Bruneel MF, et al. (September 2001). "Characteristics of sirolimus-associated interstitial pneumonitis in renal transplant patients". Transplantation. 72 (5): 787–790. doi:10.1097/00007890-200109150-00008. PMID 11571438. S2CID 12116798.

- ^ Filippone EJ, Carson JM, Beckford RA, Jaffe BC, Newman E, Awsare BK, et al. (September 2011). "Sirolimus-induced pneumonitis complicated by pentamidine-induced phospholipidosis in a renal transplant recipient: a case report". Transplantation Proceedings. 43 (7): 2792–2797. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.06.060. PMID 21911165. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Pham PT, Pham PC, Danovitch GM, Ross DJ, Gritsch HA, Kendrick EA, et al. (April 2004). "Sirolimus-associated pulmonary toxicity". Transplantation. 77 (8): 1215–1220. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000118413.92211.B6. PMID 15114088. S2CID 24496443.

- ^ Mingos MA, Kane GC (December 2005). "Sirolimus-induced interstitial pneumonitis in a renal transplant patient" (PDF). Respiratory Care. 50 (12): 1659–1661. PMID 16318648. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Das BB, Shoemaker L, Subramanian S, Johnsrude C, Recto M, Austin EH (March 2007). "Acute sirolimus pulmonary toxicity in an infant heart transplant recipient: case report and literature review". The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 26 (3): 296–298. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2006.12.004. PMID 17346635.

- ^ Delgado JF, Torres J, José Ruiz-Cano M, Sánchez V, Escribano P, Borruel S, et al. (September 2006). "Sirolimus-associated interstitial pneumonitis in 3 heart transplant recipients". The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 25 (9): 1171–1174. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2006.05.013. PMID 16962483.

- ^ McWilliams TJ, Levvey BJ, Russell PA, Milne DG, Snell GI (February 2003). "Interstitial pneumonitis associated with sirolimus: a dilemma for lung transplantation". The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 22 (2): 210–213. doi:10.1016/S1053-2498(02)00564-8. PMID 12581772.

- ^ Aparicio G, Calvo MB, Medina V, Fernández O, Jiménez P, Lema M, et al. (August 2009). "Comprehensive lung injury pathology induced by mTOR inhibitors". Clinical & Translational Oncology. 11 (8): 499–510. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0394-y. hdl:2183/19864. PMID 19661024. S2CID 39914334.

- ^ Paris A, Goupil F, Kernaonet E, Foulet-Rogé A, Molinier O, Gagnadoux F, et al. (January 2012). "[Drug-induced pneumonitis due to sirolimus: an interaction with atorvastatin?]". Revue des Maladies Respiratoires (in French). 29 (1): 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2010.03.026. PMID 22240222.

- ^ Maroto JP, Hudes G, Dutcher JP, Logan TF, White CS, Krygowski M, et al. (May 2011). "Drug-related pneumonitis in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with temsirolimus". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (13): 1750–1756. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2235. PMID 21444868.

- ^ Errasti P, Izquierdo D, Martín P, Errasti M, Slon F, Romero A, et al. (October 2010). "Pneumonitis associated with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in renal transplant recipients: a single-center experience". Transplantation Proceedings. 42 (8): 3053–3054. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.066. PMID 20970608.

- ^ Euvrard S, Morelon E, Rostaing L, Goffin E, Brocard A, Tromme I, et al. (July 2012). "Sirolimus and secondary skin-cancer prevention in kidney transplantation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (4): 329–339. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1204166. hdl:2445/178597. PMID 22830463.

- ^ Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN (August 1991). "Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast". Science. 253 (5022): 905–909. Bibcode:1991Sci...253..905H. doi:10.1126/science.1715094. PMID 1715094. S2CID 9937225.

- ^ a b c Ferron GM, Mishina EV, Zimmerman JJ, Jusko WJ (April 1997). "Population pharmacokinetics of sirolimus in kidney transplant patients". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 61 (4): 416–428. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90192-2. PMID 9129559.

- ^ Leung LY, Lim HK, Abell MW, Zimmerman JJ (February 2006). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolic disposition of sirolimus in healthy male volunteers after a single oral dose". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 28 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000179838.33020.34. PMID 16418694.

- ^ McAlister VC, Mahalati K, Peltekian KM, Fraser A, MacDonald AS (June 2002). "A clinical pharmacokinetic study of tacrolimus and sirolimus combination immunosuppression comparing simultaneous to separated administration". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 24 (3): 346–350. doi:10.1097/00007691-200206000-00004. PMID 12021624. S2CID 34950948.

- ^ a b c Schwecke T, Aparicio JF, Molnár I, König A, Khaw LE, Haydock SF, et al. (August 1995). "The biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide immunosuppressant rapamycin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (17): 7839–7843. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.7839S. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.17.7839. PMC 41241. PMID 7644502.

- ^ Gregory MA, Gaisser S, Lill RE, Hong H, Sheridan RM, Wilkinson B, et al. (May 2004). "Isolation and characterization of pre-rapamycin, the first macrocyclic intermediate in the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin by S. hygroscopicus". Angewandte Chemie. 43 (19): 2551–2553. doi:10.1002/anie.200453764. PMID 15127450.

- ^ Gregory MA, Hong H, Lill RE, Gaisser S, Petkovic H, Low L, et al. (October 2006). "Rapamycin biosynthesis: Elucidation of gene product function". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 4 (19): 3565–3568. doi:10.1039/b608813a. PMID 16990929.

- ^ Graziani EI (May 2009). "Recent advances in the chemistry, biosynthesis and pharmacology of rapamycin analogs". Natural Product Reports. 26 (5): 602–609. doi:10.1039/b804602f. PMID 19387497.

- ^ Gatto GJ, Boyne MT, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT (March 2006). "Biosynthesis of pipecolic acid by RapL, a lysine cyclodeaminase encoded in the rapamycin gene cluster". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (11): 3838–3847. doi:10.1021/ja0587603. PMID 16536560.

- ^ Aparicio JF, Molnár I, Schwecke T, König A, Haydock SF, Khaw LE, et al. (February 1996). "Organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for rapamycin in Streptomyces hygroscopicus: analysis of the enzymatic domains in the modular polyketide synthase". Gene. 169 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(95)00800-4. PMID 8635756.

- ^ Li Q, Rao R, Vazzana J, Goedegebuure P, Odunsi K, Gillanders W, et al. (April 2012). "Regulating mammalian target of rapamycin to tune vaccination-induced CD8(+) T cell responses for tumor immunity". Journal of Immunology. 188 (7): 3080–3087. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103365. PMC 3311730. PMID 22379028.

- ^ Easton JB, Houghton PJ (October 2006). "mTOR and cancer therapy". Oncogene. 25 (48): 6436–6446. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209886. PMID 17041628. S2CID 19250234.

- ^ Law BK (October 2005). "Rapamycin: an anti-cancer immunosuppressant?". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 56 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.09.009. PMID 16039868.

- ^ "A new role for sirolimus: regression of Kaposi's sarcoma in kidney-transplant recipients". Nature Clinical Practice Urology. 2 (5): 211. May 2005. doi:10.1038/ncponc0156x. ISSN 1743-4289. S2CID 198175394.

- ^ Bankhead C (17 February 2013). "Fatal AEs Higher with mTOR Drugs in Cancer". Med Page Today. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Sun SY, Rosenberg LM, Wang X, Zhou Z, Yue P, Fu H, et al. (August 2005). "Activation of Akt and eIF4E survival pathways by rapamycin-mediated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition". Cancer Research. 65 (16): 7052–7058. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. PMID 16103051.

- ^ Chan S (October 2004). "Targeting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): a new approach to treating cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 91 (8): 1420–1424. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602162. PMC 2409926. PMID 15365568.

- ^ Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, Malina A, Ray S, Kogan S, et al. (March 2004). "Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy". Nature. 428 (6980): 332–337. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..332W. doi:10.1038/nature02369. PMID 15029198. S2CID 4426215.

- ^ "Combination therapy drives cancer into remission". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Novak K (May 2004). "Therapeutics: Means to an end". Nature Reviews Cancer. 4 (5): 332. doi:10.1038/nrc1349. S2CID 45906785.

- ^ Li M, Zhou Y, Chen C, Yang T, Zhou S, Chen S, et al. (February 2019). "Efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogues) for tuberous sclerosis complex: a meta-analysis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 14 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s13023-019-1012-x. PMC 6373010. PMID 30760308.

- ^ Lawton G. "What is rapamycin?". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Arriola Apelo SI, Lamming DW (July 2016). "Rapamycin: An InhibiTOR of Aging Emerges From the Soil of Easter Island". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 71 (7): 841–849. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw090. PMC 4906330. PMID 27208895.

A diverse and severe set of negative side effects likely preclude the wide-scale use of rapamycin and its analogs as a prolongevity agent.

- ^ Strong R, Miller RA, Bogue M, Fernandez E, Javors MA, Libert S, et al. (November 2020). "Rapamycin-mediated mouse lifespan extension: Late-life dosage regimes with sex-specific effects". Aging Cell. 19 (11): e13269. doi:10.1111/acel.13269. PMC 7681050. PMID 33145977.

- ^ "Late-Life Rapamycin Regimens Extend Mouse Lifespan in a Sex-Specific Manner". Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN). 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Mannick JB, Del Giudice G, Lattanzi M, Valiante NM, Praestgaard J, Huang B, et al. (December 2014). "mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly". Science Translational Medicine. 6 (268): 268ra179. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009892. PMID 25540326. S2CID 206685475.

- ^ Janin A (May 2023). "Can a Kidney Transplant Drug Keep You From Aging?". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M (January 2013). "mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease". Nature. 493 (7432): 338–345. Bibcode:2013Natur.493..338J. doi:10.1038/nature11861. PMC 3687363. PMID 23325216.

- ^ Smith, Dana. "Anti-Aging Enthusiasts Are Taking a Pill to Extend Their Lives. Will It Work?" The New York Times, 24 Sept. 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/24/well/live/rapamycin-aging-longevity-benefits-risks.html

- ^ Weichhart T, Hengstschläger M, Linke M (October 2015). "Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 15 (10): 599–614. doi:10.1038/nri3901. PMC 6095456. PMID 26403194.

- ^ Chung CL, Lawrence I, Hoffman M, Elgindi D, Nadhan K, Potnis M, et al. (December 2019). "Topical rapamycin reduces markers of senescence and aging in human skin: an exploratory, prospective, randomized trial". GeroScience. 41 (6): 861–869. doi:10.1007/s11357-019-00113-y. PMC 6925069. PMID 31761958.

- ^ a b Husain A, Byrareddy SN (November 2020). "Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 331: 109282. Bibcode:2020CBI...33109282H. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109282. PMC 7536130. PMID 33031791.

- ^ Liu Y, Yang F, Zou S, Qu L (2019). "Rapamycin: A Bacteria-Derived Immunosuppressant That Has Anti-atherosclerotic Effects and Its Clinical Application". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9: 1520. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01520. PMC 6330346. PMID 30666207.

- ^ Stocker R, Keaney JF (October 2004). "Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis". Physiological Reviews. 84 (4): 1381–1478. doi:10.1152/physrev.00047.2003. PMID 15383655.

- ^ a b Oaks Z, Winans T, Huang N, Banki K, Perl A (December 2016). "Activation of the Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin in SLE: Explosion of Evidence in the Last Five Years". Current Rheumatology Reports. 18 (12): 73. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0622-8. PMC 5314949. PMID 27812954.

- ^ Wiegand S, Dietz A, Wichmann G (August 2022). "Efficacy of sirolimus in children with lymphatic malformations of the head and neck". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 279 (8): 3801–3810. doi:10.1007/s00405-022-07378-8. PMC 9249683. PMID 35526176.

- ^ Lutz M, Mielke S (November 2016). "New perspectives on the use of mTOR inhibitors in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and graft-versus-host disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 82 (5): 1171–1179. doi:10.1111/bcp.13022. PMC 5061796. PMID 27245261.

- ^ Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Vallera DA (June 1998). "Rapamycin inhibits the generation of graft-versus-host disease- and graft-versus-leukemia-causing T cells by interfering with the production of Th1 or Th1 cytotoxic cytokines". Journal of Immunology. 160 (11): 5355–5365. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.160.11.5355. PMID 9605135. S2CID 31313976.

- ^ Ehx G, Ritacco C, Hannon M, Dubois S, Delens L, Willems E, et al. (August 2021). "Comprehensive analysis of the immunomodulatory effects of rapamycin on human T cells in graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis". American Journal of Transplantation. 21 (8): 2662–2674. doi:10.1111/ajt.16505. hdl:2268/256132. PMID 33512760. S2CID 231766741.

- ^ Rivera VM, Clackson T, Natesan S, Pollock R, Amara JF, Keenan T, et al. (September 1996). "A humanized system for pharmacologic control of gene expression". Nature Medicine. 2 (9): 1028–1032. doi:10.1038/nm0996-1028. PMID 8782462. S2CID 30469863.

- ^

- "Study to assess healthy aging in dogs: the Dog Aging Project and Test of Rapamycin in Aging Dogs (TRIAD study)". University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine. 29 July 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Dog Aging Project TRIAD Study". Washington State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Dog aging project - TRIAD (Test of Rapamycin in Aging Dogs)". Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Benjamin D, Colombi M, Moroni C, Hall MN (October 2011). "Rapamycin passes the torch: a new generation of mTOR inhibitors". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 10 (11): 868–880. doi:10.1038/nrd3531. PMID 22037041. S2CID 1227277.

- Freixo C, Ferreira V, Martins J, Almeida R, Caldeira D, Rosa M, et al. (January 2020). "Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in the treatment of vascular anomalies: A systematic review". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 71 (1): 318–327. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.06.217. PMID 31676179. S2CID 207831199.

- Geeurickx M, Labarque V (September 2021). "A narrative review of the role of sirolimus in the treatment of congenital vascular malformations". Journal of Vascular Surgery. Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. 9 (5): 1321–1333. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2021.03.001. PMID 33737259.

External links

[edit]- Clinical trial number NCT02494570 for "A Phase 2 Study of ABI-009 in Patients With Advanced Malignant PEComa (AMPECT)" at ClinicalTrials.gov