Tranilast

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.150.125 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

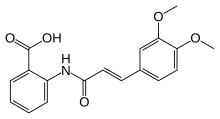

| Formula | C18H17NO5 |

| Molar mass | 327.336 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Tranilast (INN, brand name Rizaben) is an antiallergic drug. It was developed by Kissei Pharmaceuticals and was approved in 1982 for use in Japan and South Korea for bronchial asthma. Indications for keloid and hypertrophic scar were added in the 1980s.

Medical uses

[edit]It is used in Japan, South Korea, and China to treat asthma, keloid scars, and hypertrophic scars, and as an ophthalmic solution for allergic pink eye.[1]

It should not be taken by women who are or might become pregnant, and it is secreted in breast milk.[1]

Interactions

[edit]People who are taking warfarin should not also take tranilast, as they interact.[1] It appears to inhibit UGT1A1 so will interfere with metabolism of drugs that are affected by that enzyme.[1]

Adverse effects

[edit]When given systemically, tranilast appears to cause liver damage; in a large well-conducted clinical trial it caused elevated transaminases three times the upper limit of normal in 11 percent of patients, as well as anemia, kidney failure, rash, and problems urinating.[1]

Given systemically it inhibits blood formation, causing leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia.[1]

Society and culture

[edit]As of March 2018 it was marketed in Japan, China, and South Korea under the brand names Ao Te Min, Arenist, Brecrus, Garesirol, Hustigen, Krix, Lumios, Rizaben, Tramelas, Tranilast, and it was marketed as a combination drug with salbutamol under the brand name Shun Qi.[2]

In 2016 the FDA proposed that tranilast be excluded from the list of active pharmaceutical ingredients that compounding pharmacies in the US could formulate with a prescription.[1]

Pharmacology

[edit]It appears to work by inhibiting the release of histamine from mast cells; it has been found to inhibit proliferation of fibroblasts but its biological target is not known.[3] It has been shown to inhibit the release of many cytokines in various cell types, in in vitro studies.[3] It has also been shown to inhibit NALP3 inflammasome activation and is being studied as a treatment for NALP3-driven inflammatory diseases.[4] It has also been found to block the ion channel TRPV2.[5]

Chemistry

[edit]Tranilast is an analog of a metabolite of tryptophan, and its chemical name is 3′,4′-dimethoxycinnamoyl) anthranilic acid (N-5′).[3]

It is almost insoluble in water, easily soluble in dimethylsulfoxide, soluble in dioxane, and very slightly soluble in ether. It is photochemically unstable in solution.[3]

Research

[edit]After promising results in three small clinical trials, tranilast was studied in a major clinical trial (the PRESTO trial) by SmithKline Beecham in partnership with Kissei for prevention of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary revascularization,[6] but was not found effective for that application.[1][7]

As of 2016, Altacor was developing a formulation of tranilast to prevent of scarring following glaucoma surgery and had obtained an orphan designation from the EMA for this use.[8][9]

History

[edit]It was developed by Kissei and first approved in Japan and South Korea for asthma in 1982, and approved uses for keloid and hypertrophic scars were added later in the 1980s.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "FDA Proposed Rules" (PDF). Federal Register. 81 (242): 91071–91082. December 16, 2016. Another version of same published at here

- ^ "International brands for Tranilast". Drugs.com. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Darakhshan S, Pour AB (January 2015). "Tranilast: a review of its therapeutic applications". Pharmacological Research. 91: 15–28. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.10.009. PMID 25447595.

- ^ Huang Y, Jiang H, Chen Y, Wang X, Yang Y, Tao J, Deng X, Liang G, Zhang H, Jiang W, Zhou R (April 2018). "Tranilast directly targets NLRP3 to treat inflammasome-driven diseases". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 10 (4). doi:10.15252/emmm.201708689. PMC 5887903. PMID 29531021.

- ^ Perálvarez-Marín A, Doñate-Macian P, Gaudet R (November 2013). "What do we know about the transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 (TRPV2) ion channel?". The FEBS Journal. 280 (21): 5471–87. doi:10.1111/febs.12302. PMC 3783526. PMID 23615321.

- ^ "Kissei's existing business flat but R&D pipeline should lead to growth". The Pharma Letter. 8 September 2000.

- ^ Holmes DR, Savage M, LaBlanche JM, Grip L, Serruys PW, Fitzgerald P, et al. (September 2002). "Results of Prevention of REStenosis with Tranilast and its Outcomes (PRESTO) trial". Circulation. 106 (10): 1243–50. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000028335.31300.DA. hdl:1765/9972. PMID 12208800.

- ^ "Tranilast - Altacor: ALT-401". AdisInsight. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "EU/3/10/756 Orphan Designation". European Medicines Agency. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2018.