Clostridium sporogenes

| Clostridium sporogenes | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia |

| Order: | Eubacteriales |

| Family: | Clostridiaceae |

| Genus: | Clostridium |

| Species: | C. sporogenes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clostridium sporogenes (Metchnikoff 1908) Bergey et al. 1923[1]

| |

Clostridium sporogenes is a species of Gram-positive bacteria that belongs to the genus Clostridium. Like other strains of Clostridium, it is an anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that produces oval, subterminal endospores[2] and is commonly found in soil. Unlike Clostridium botulinum, it does not produce the botulinum neurotoxins. In colonized animals, it has a mutualistic rather than pathogenic interaction with the host.

It is being investigated as a way to deliver cancer-treating drugs to tumours in patients.[3] C. sporogenes is often used as a surrogate for C. botulinum when testing the efficacy of commercial sterilisation.[4]

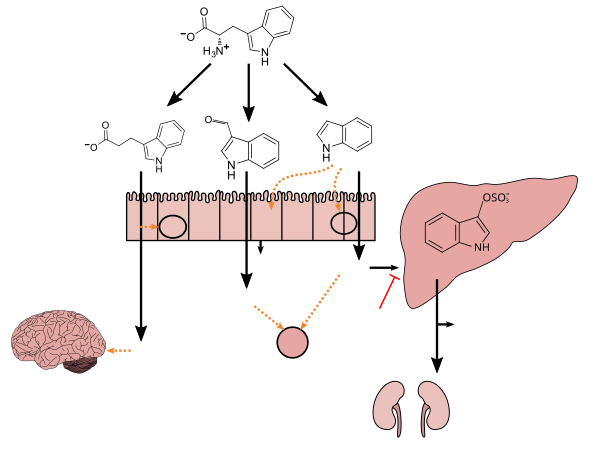

Clostridium sporogenes colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract, but is only present in a subset of the population; in the intestine, it uses tryptophan to synthesize indole and subsequently 3-indolepropionic acid (IPA)[5] – a type of auxin (plant hormone)[6][7] – which serves as a potent neuroprotective antioxidant within the human body and brain.[5][8][9][10] IPA is an even more potent scavenger of hydroxyl radicals than melatonin.[8][9][10] Similar to melatonin but unlike other antioxidants, it scavenges radicals without subsequently generating reactive and pro-oxidant intermediate compounds.[8][9][11] C. sporogenes is the only species of bacteria known to synthesize 3-indolepropionic acid in vivo at levels which are subsequently detectable in the blood stream of the host.[5][12]

Tryptophan metabolism by human gut microbiota ()

|

References

[edit]- ^ Parker, Charles Thomas; Taylor, Dorothea; Garrity, George M. (2009). Parker, Charles Thomas; Garrity, George M (eds.). "Clostridium sporogenes". US Department of Energy. doi:10.1601/nm.4021. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ microbeonline.com; information with figure illustrating the subterminal endospore location in the vegetative cell.

- ^ BBC News "Soil bacterium helps kill cancers."

- ^ Development of novel biological indicators to evaluate the efficacy of microwave processing. p. 7. ISBN 9780549830450.

- ^ a b c d Wikoff WR, Anfora AT, Liu J, Schultz PG, Lesley SA, Peters EC, Siuzdak G (March 2009). "Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (10): 3698–3703. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3698W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812874106. PMC 2656143. PMID 19234110.

Production of IPA was shown to be completely dependent on the presence of gut microflora and could be established by colonization with the bacterium Clostridium sporogenes.

IPA metabolism diagram - ^ Lu Q, Zhang L, Chen T, Lu M, Ping T, Chen G (2008). "Identification and quantitation of auxins in plants by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry". Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22 (16): 2565–72. Bibcode:2008RCMS...22.2565L. doi:10.1002/rcm.3642. PMID 18655000.

- ^ Narayanan KR, Mudge KW, Poovaiah BW (1981). "In vitro auxin binding to cellular membranes of cucumber fruits". Plant Physiol. 67 (4): 836–40. doi:10.1104/pp.67.4.836. PMC 425782. PMID 16661764.

- ^ a b c d "3-Indolepropionic acid". Human Metabolome Database. University of Alberta. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Omar RA, Chain DG, Frangione B, Ghiso J, Pappolla MA (July 1999). "Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer beta-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (31): 21937–21942. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.31.21937. PMID 10419516. S2CID 6630247.

[Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA)] has previously been identified in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of humans, but its functions are not known. ... In kinetic competition experiments using free radical-trapping agents, the capacity of IPA to scavenge hydroxyl radicals exceeded that of melatonin, an indoleamine considered to be the most potent naturally occurring scavenger of free radicals. In contrast with other antioxidants, IPA was not converted to reactive intermediates with pro-oxidant activity.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zhang LS, Davies SS (April 2016). "Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions". Genome Med. 8 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x. PMC 4840492. PMID 27102537.

Lactobacillus spp. convert tryptophan to indole-3-aldehyde (I3A) through unidentified enzymes [125]. Clostridium sporogenes convert tryptophan to IPA [6], likely via a tryptophan deaminase. ... IPA also potently scavenges hydroxyl radicals

Table 2: Microbial metabolites: their synthesis, mechanisms of action, and effects on health and disease

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of action of indole and its metabolites on host physiology and disease - ^ Reiter RJ, Guerrero JM, Garcia JJ, Acuña-Castroviejo D (1998). "Reactive oxygen intermediates, molecular damage, and aging. Relation to melatonin". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 854 (1): 410–24. Bibcode:1998NYASA.854..410R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09920.x. PMID 9928448. S2CID 29333394.

- ^ Attwood G, Li D, Pacheco D, Tavendale M (2006). "Production of indolic compounds by rumen bacteria isolated from grazing ruminants". J. Appl. Microbiol. 100 (6): 1261–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02896.x. PMID 16696673. S2CID 35673610.

External links

[edit]