Cryptococcus neoformans

| Cryptococcus neoformans | |

|---|---|

| |

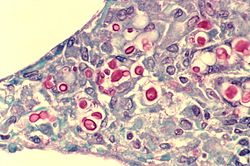

| Yeast state of Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Tremellomycetes |

| Order: | Tremellales |

| Family: | Cryptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Cryptococcus |

| Species: | C. neoformans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans (San Felice) Vuill. (1901)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Saccharomyces neoformans San Felice (1895) | |

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated basidiomycetous yeast[1] belonging to the class Tremellomycetes and an obligate aerobe[2] that can live in both plants and animals. Its teleomorph is a filamentous fungus, formerly referred to Filobasidiella neoformans. In its yeast state, it is often found in bird excrement. It has remarkable genomic plasticity and genetic variability between its strains, making treatment of the disease it causes difficult.[3] Cryptococcus neoformans causes disease primarily in immunocompromised hosts, such as HIV or cancer patients.[1][4][5] In addition it has been shown to cause disease in apparently immunocompetent hosts, especially in developed countries.

Classification

[edit]Cryptococcus neoformans has undergone numerous nomenclature revisions since its first description in 1895. It formerly contained two varieties: C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. neoformans var. grubii. A third variety, C. neoformans var. gattii, was later defined as a distinct species, Cryptococcus gattii. The most recent classification system divides these varieties into seven species.[6] C. neoformans refers to C. neoformans var. grubii. A new species name, Cryptococcus deneoformans, is used for the former C. neoformans var. neoformans. C. gattii is divided into five species.[citation needed]

The teleomorph was first described in 1975 by K.J. Kwon-Chung, who obtained cultures of Filobasidiella neoformans by crossing strains of the yeast C. neoformans. She was able to observe basidia similar to those of the genus Filobasidium, hence the name Filobasidiella for the new genus.[7] Following changes to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, the practice of giving different names to teleomorph and anamorph forms of the same fungus was discontinued, meaning that Filobasidiella neoformans became a synonym of the earlier name Cryptococcus neoformans.[citation needed]

Characteristics

[edit]

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (February 2020) |

Cryptococcus neoformans typically grows as a yeast (unicellular) and replicates by budding. It makes hyphae during mating, and eventually creates basidiospores at the end of the hyphae before producing spores. Under host-relevant conditions, including low glucose, serum, 5% carbon dioxide, and low iron, among others, the cells produce a characteristic polysaccharide capsule.[8] The recognition of C. neoformans in Gram-stained smears of purulent exudates may be hampered by the presence of the large gelatinous capsule which apparently prevents definitive staining of the yeast-like cells. In such stained preparations, it may appear either as round cells with Gram-positive granular inclusions impressed upon a pale lavender cytoplasmic background or as Gram-negative lipoid bodies.[9] When grown as a yeast, C. neoformans has a prominent capsule composed mostly of polysaccharides. Under the microscope, the India ink stain is used for easy visualization of the capsule in cerebral spinal fluid.[10] The particles of ink pigment do not enter the capsule that surrounds the spherical yeast cell, resulting in a zone of clearance or "halo" around the cells. This allows for quick and easy identification of C. neoformans. Unusual morphological forms are rarely seen.[11] For identification in tissue, mucicarmine stain provides specific staining of polysaccharide cell wall in C. neoformans. Cryptococcal antigen from cerebrospinal fluid is thought to be the best test for diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis in terms of sensitivity, though it might be unreliable in HIV-positive patients.[12]

The first genome sequence for a strain of C. neoformans (var. neoformans; now C. deneoformans) was published in 2005.[5]

Studies suggest that colonies of C. neoformans and related fungi growing within the ruins of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant may be able to metabolize ionizing radiation.[13]

Pathology

[edit]Infection with C. neoformans is termed cryptococcosis. Most infections with C. neoformans occur in the lungs, as the fungus enters its host through the respiratory route.[14] Because it is normally a harmless soil fungus, C. neoformans must first adapt to its new environment inside the human body, making several virulent transformations, including the formation of a polysaccharide capsule. The specific factors that enable this transformation involve sensory receptor proteins common to most soil fungi (pH sensors, carbon dioxide sensors, and intracellular iron detectors) which have been adapted to induce C. neoformans cells into rapidly becoming a dangerous, disease-causing organism.[15]

The fungus is a facultative intracellular pathogen[16] that can utilize host phagocytes to spread within the body.[17][18] C. neoformans was the first intracellular pathogen for which the non-lytic escape process termed vomocytosis was observed.[19][20] It has been speculated that this ability to manipulate host cells results from environmental selective pressure by amoebae, a hypothesis first proposed by Arturo Casadevall under the term "accidental virulence".[21]

In human infection, C. neoformans is spread by inhalation of aerosolized basidiospores or dehydrated fungal cells, and can disseminate to the central nervous system, where it can cause meningoencephalitis.[22] In the lungs, C. neoformans cells are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages.[23] Macrophages produce oxidative and nitrosative agents, creating a hostile environment, to kill invading pathogens.[24] However, some C. neoformans cells can survive intracellularly in macrophages because of the protective nature of the polysaccharide capsule as well as its ability to produce melanin.[23][3] Intracellular survival appears to be one of the factors contributing to latency, disseminated disease, and resistance to eradication by antifungal agents. One mechanism by which C. neoformans survives the hostile intracellular environment of the macrophage involves upregulation of expression of genes involved in responses to oxidative stress.[23]

Traversal of the blood–brain barrier by C. neoformans plays a key role in meningitis pathogenesis.[25] However, precise mechanisms by which it passes the blood-brain barrier are still unknown; a 2014 study in rats suggested an important role of secreted serine proteases.[26] The metalloprotease Mpr1 has been demonstrated to be critical in blood-brain barrier penetration.[27]

AIDS

[edit]Fungal meningitis and encephalitis are frequently associated with HIV-positive patients with low T-cell counts. C. neoformans is one of the illnesses that definitionally marks the point at which a person with HIV may be considered to have AIDS.[28] Infections with this fungus were thought to be rare in people with fully functioning immune systems, hence C. neoformans is often referred to as an opportunistic pathogen.[1] However, a study from 2024 done in Australia and New Zealand showed the vast majority of recorded infections to be in non-HIV patients.[5]

Changes in reproductive pattern

[edit]The vast majority of environmental and clinical isolates of C. neoformans are mating type alpha. Filaments of mating type alpha have haploid nuclei ordinarily, but these can undergo a process of diploidization (perhaps by endoduplication or stimulated nuclear fusion) to form diploid cells termed blastospores. The diploid nuclei of blastospores are able to undergo meiosis, including recombination, to form haploid basidiospores that can then be dispersed.[29] This process is referred to as monokaryotic fruiting. Required for this process is a gene designated dmc1, a conserved homologue of genes recA in bacteria, and rad51 in eukaryotes (see articles recA and rad51). Dmc1 mediates homologous chromosome pairing during meiosis and repair of double-strand breaks in DNA.[30] One benefit of meiosis in C. neoformans could be to promote DNA repair in the DNA-damaging environment caused by the oxidative and nitrosative agents produced in macrophages.[29] Thus, C. neoformans can undergo a meiotic process, monokaryotic fruiting, that may promote recombinational repair in the oxidative, DNA-damaging environment of the host macrophage, and this may contribute to its virulence.[citation needed]

Serious complications of human infection

[edit]Infection begins in the lungs, and from there the fungus can disseminate to the brain and other body parts via macrophages. An infection of the brain caused by C. neoformans is referred to as cryptococcal meningitis, which is most often fatal when left untreated.[5][31] Cryptococcal meningitis causes more than 180,000 deaths annually.[32] CNS (central nervous system) infections may also be present as a brain abscesses known as cryptococcomas, subdural effusions, dementia, isolated cranial nerve lesions, spinal cord lesions, and ischemic stroke. The estimated one-year mortality of HIV-related people who receive treatment for cryptococcal meningitis is 70% in low-income countries versus 20–30% for high-income countries.[33] Symptoms include headache, fever, neck stiffness, nausea and vomiting, photophobia. Diagnosis methods include a serum cryptococcal antigen test and lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination to detect C. neoformans.[34]

Treatment

[edit]

Cryptococcosis that does not affect the central nervous system can be treated with fluconazole alone.

It was recommended in 2000 that cryptococcal meningitis be treated for two weeks with intravenous amphotericin B 0.7–1.0 mg/kg per day and oral flucytosine 100 mg/kg per day (or intravenous flucytosine 75 mg/kg per day[citation needed]day if the patient is unable to swallow), followed by oral fluconazole 400–800 mg daily for ten weeks[3] and then 200 mg daily for at least one year and until the patient's CD4 count is above 200 cells/mcl.[35][36] Flucytosine is a generic, off-patent medicine, but the cost of two weeks of flucytosine therapy is about US$10,000,[citation needed] so that flucytosine has been unavailable in low- and middle-income countries. In 1970, flucytosine was available in Africa.[37] A dose of 200 mg/kg per day of flucytosine is associated with more side effects but is not more effective.[citation needed]

A single high dose of liposomal amphotericin B with 14 days of flucytosine and fluconazole is recommended by the newest WHO guideline for cryptococcal meningitis.[38] A new study found that brain glucose can trigger amphotericin B (AmB) tolerance of C. neoformans during meningitis which means it needs longer treatment time to kill the fungal cells. The study found that the brain glucose induced AmB tolerance of C. neoformans via glucose repression activator Mig1. Mig1 inhibits the production of ergosterol, the target of AmB, and promotes the production of inositol phosphoryl ceramide (IPC), which competes with AmB for ergosterol to limit AmB efficacy in mouse brain and human CSF. Strikingly, Results of this study indicated that IPC synthase inhibitor aureobasidin A (AbA) can enhance the anti-cryptococcal activity of AmB. AbA+AmB AmB had an even better therapeutic effect in a mouse model of cryptococcal meningitis than AmB+flucytosine which may bring new hope for the treatment of Cryptococcal meningitis.[32]

In Africa, oral fluconazole at a rate of 200 mg daily is often used. However, this does not result in cure, because it merely suppresses the fungus and does not kill it; viable fungus can continue to be grown from cerebrospinal fluid of patients not having taken fluconazole for many months. An increased dose of 400 mg daily does not improve outcomes,[39] but prospective studies from Uganda and Malawi reported that higher doses of 1200 mg per day have more fungicidal activity.[40] The outcomes with fluconazole monotherapy have 30% worse survival than amphotericin-based therapies, in a recent systematic review.[41]

The current treatment options for cryptococcosis are not optimal for treatment.[3] AmB is highly toxic to humans, and both fluconazole and flucytosine have been shown to cause development of drug resistanse in C. neoformans. A recent study from 2024 suggested brilacidin as an alternative treatment option.[36] Brilacidin was shown to be non-toxic and it caused no drug resistance development in C. neoformans, while still being efficient at causing fungal mortality. Brilacidin enhances permiability of the cell wall and membrane by binding to ergosterol and disrupting its distribution. It also affects the cell wall integrity pathway and disrupts calsium metabolism. Through these methods it not only causes cell mortality on its own, but also enables more effective use of other antifungal agents such as AmB against C. neoformans.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Buchanan, Kent; Murphy, J. W. (1998). "What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen?". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (1): 71–83. doi:10.3201/eid0401.980109. PMC 2627665. PMID 9452400.

- ^ Ingavale, Susham S.; Chang, Yun C.; Lee, Hyeseung; McClelland, Carol M.; Leong, Madeline L.; Kwon-Chung, Kgung J. (2008-09-01). "Importance of mitochondria in survival of Cryptococcus neoformans under low oxygen conditions and tolerance to Cobalt Chloride". PLOS Pathogens. 4 (9): e1000155. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000155. ISSN 1553-7366. PMC 2528940. PMID 18802457.

- ^ a b c d Melhem, Marcia; Júnior, Diniz; Takahashi, Juliana; Macioni, Milena; Oliveira, Lidiane; Siufi de Araújo, Lisandra; Fava, Wellington; Bonfietti, Lucas; Paniago, Anamaria; Venturini, James; Espinel-Ingroff, Ana (29 January 2024). "Antifungal Resistance in Cryptococcal Infections". Pathogens. 13 (2): 128. doi:10.3390/pathogens13020128. PMC 10891860. PMID 38392866.

- ^ Bahn, Yong-Sun; Sun, Sheng; Heitman, Joseph; Lin, Xiaorong (2020-09-01). "Microbe Profile: Cryptococcus neoformans species complex". Microbiology. 166 (9): 797–799. doi:10.1099/mic.0.000973. ISSN 1350-0872. PMC 7717486. PMID 32956032.

- ^ a b c d Coussement, Julien; Heath, Christopher; Roberts, Matthew; Lane, Rebekah; Spelman, Tim; Smibert, Olivia; Longhitano, Anthony; Morrisey, Orla; Nield, Blake; Tripathy, Monica; Davis, Joshua; Kennedy, Karina; Lynar, Sarah; Crawford, Lucy; Slavin, Monica (26 May 2023). "Current Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Cryptococcus Infection in Patients Without Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Multicenter Study in 46 Hospitals in Australia and New Zealand". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 77 (7): 976–986. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad321. PMID 37235212.

- ^ Hagen, Ferry; Khayhan, Kantarawee; Theelen, Bart; Kolecka, Anna; Polacheck, Itzhack; Sionov, Edward; Falk, Rama; Parnmen, Sittiporn; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten (2015-05-01). "Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 78: 16–48. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2015.02.009. ISSN 1096-0937. PMID 25721988.

- ^ Kwon-Chung KJ. (1975). "A new genus, Filobasidiella, the perfect state of Cryptococcus neoformans". Mycologia. 67 (6): 1197–1200. doi:10.2307/3758842. JSTOR 3758842. PMID 765816.

- ^ Heitman, Joseph; Kozel, Thomas R.; Kwon-Chung, Kyung J.; Perfect, John R.; Casadevall, Arturo, eds. (2011). Cryptococcus: From Human Pathogen to Model Yeast. Washington, DC: ASM Press. doi:10.1128/9781555816858. ISBN 9781683671220.

- ^ Bottone, E J (1980). "Cryptococcus neoformans: pitfalls in diagnosis through evaluation of gram-stained smears of purulent exudates". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 12 (6): 790–1. doi:10.1128/jcm.12.6.790-791.1980. PMC 273699. PMID 6171578.

- ^ Zerpa, R; Huicho, L; Guillén, A (September 1996). "Modified India ink preparation for Cryptococcus neoformans in cerebrospinal fluid specimens". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 34 (9): 2290–1. doi:10.1128/JCM.34.9.2290-2291.1996. PMC 229234. PMID 8862601.

- ^ Shashikala; Kanungo, R; Srinivasan, S; Mathew, R; Kannan, M (Jul–Sep 2004). "Unusual morphological forms of Cryptococcus neoformans in cerebrospinal fluid". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 22 (3): 188–90. doi:10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02835-8. PMID 17642731.

- ^ Antinori, Spinello; Radice, Anna; Galimberti, Laura; Magni, Carlo; Fasan, Marco; Parravicini, Carlo (November 2005). "The role of cryptococcal antigen assay in diagnosis and monitoring of cryptococcal meningitis" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 43 (11): 5828–9. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.11.5828-5829.2005. PMC 1287839. PMID 16272534.

- ^ Dadachova E; et al. (2007). Rutherford, Julian (ed.). "Ionizing Radiation Changes the Electronic Properties of Melanin and Enhances the Growth of Melanized Fungi". PLOS ONE. 2 (5): e457. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..457D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000457. PMC 1866175. PMID 17520016.

- ^ Tripathi, K; Mor, V; Bairwa, NK; Del Poeta, M; Mohanty, BK (2012). "Hydroxyurea treatment inhibits proliferation of Cryptococcus neoformans in mice". Front Microbiol. 3: 187. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00187. PMC 3390589. PMID 22783238.

- ^ Alspaugh, J. Andrew (May 2015). ""Virulence Mechanisms and Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis"". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 78: 55–58. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2014.09.004. ISSN 1087-1845. PMC 4370805. PMID 25256589.

- ^ Alvarez, M.; Burns, T.; Luo, Y.; Pirofski, L. A.; Casadevall, A. (2009). "The outcome of Cryptococcus neoformans intracellular pathogenesis in human monocytes". BMC Microbiology. 9: 51. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-9-51. PMC 2670303. PMID 19265539.

- ^ Charlier, C; Nielsen, K; Daou, S; Brigitte, M; Chretien, F; Dromer, F (January 2009). "Evidence of a role for monocytes in dissemination and brain invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans". Infection and Immunity. 77 (1): 120–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.336.3329. doi:10.1128/iai.01065-08. PMC 2612285. PMID 18936186.

- ^ Sabiiti, W; Robertson, E; Beale, MA; Johnston, SA; Brouwer, AE; Loyse, A; Jarvis, JN; Gilbert, AS; Fisher, MC; Harrison, TS; May, RC; Bicanic, T (May 2014). "Efficient phagocytosis and laccase activity affect the outcome of HIV-associated cryptococcosis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (5): 2000–8. doi:10.1172/jci72950. PMC 4001551. PMID 24743149.

- ^ Alvarez, M; Casadevall, A (7 November 2006). "Phagosome extrusion and host-cell survival after Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis by macrophages". Current Biology. 16 (21): 2161–5. Bibcode:2006CBio...16.2161A. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.061. PMID 17084702. S2CID 1612240.

- ^ Ma, H; Croudace, JE; Lammas, DA; May, RC (7 November 2006). "Expulsion of live pathogenic yeast by macrophages". Current Biology. 16 (21): 2156–60. Bibcode:2006CBio...16.2156M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.032. PMID 17084701. S2CID 11639313.

- ^ Casadevall, A (2012). "Amoeba Provide Insight into the Origin of Virulence in Pathogenic Fungi". Recent Advances on Model Hosts. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 710. pp. 1–10. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-5638-5_1. ISBN 978-1-4419-5637-8. PMID 22127880.

- ^ Velagapudi R, Hsueh YP, Geunes-Boyer S, Wright JR, Heitman J (2009). "Spores as infectious propagules of Cryptococcus neoformans". Infect Immun. 77 (10): 4345–55. doi:10.1128/IAI.00542-09. PMC 2747963. PMID 19620339.

- ^ a b c Fan W, Kraus PR, Boily MJ, Heitman J (2005). "Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during murine macrophage infection". Eukaryot Cell. 4 (8): 1420–1433. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.333.7376. doi:10.1128/EC.4.8.1420-1433.2005. PMC 1214536. PMID 16087747.

- ^ Alspaugh JA, Granger DL (1991). "Inhibition of Cryptococcus neoformans replication by nitrogen oxides supports the role of these molecules as effectors of macrophage-mediated cytostasis". Infect Immun. 59 (7): 2291–2296. doi:10.1128/IAI.59.7.2291-2296.1991. PMC 258009. PMID 2050398.

- ^ Liu TB (2012). "Molecular mechanisms of cryptococcal meningitis". Virulence. 3 (2): 173–81. doi:10.4161/viru.18685. PMC 3396696. PMID 22460646.

- ^ Xu CY (Feb 2014). "permeability of blood-brain barrier is mediated by serine protease during Cryptococcus meningitis". J Int Med Res. 42 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1177/0300060513504365. PMID 24398759.

- ^ "Fungal protein found to cross blood-brain barrier". University of California at Davis. 12 June 2014 – via MedicalXpress.

- ^ "Appendix A: AIDS-Defining Conditions". cdc.gov. 2008-12-05. Archived from the original on 2025-01-01. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ a b Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J (2005). "Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans". Nature. 434 (7036): 1017–1021. Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1017L. doi:10.1038/nature03448. PMID 15846346. S2CID 52857557.

- ^ Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infect Genet Evol. 8 (3): 267–285. Bibcode:2008InfGE...8..267M. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ Bicanic, Tihana; Harrison, Thomas S. (1 January 2004). "Cryptococcal meningitis". British Medical Bulletin. 72 (1): 99–118. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh043. ISSN 1471-8391. PMID 15838017.

- ^ a b Chen, Lei; Tian, Xiuyun; Zhang, Lanyue; Wang, Wenzhao; Hu, Pengjie; et al. (15 January 2024). "Brain glucose induces tolerance of Cryptococcus neoformans to amphotericin B during meningitis". Nature Microbiology. 9 (2): 346–358. doi:10.1038/s41564-023-01561-1. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 38225460.

- ^ Rajasingham, Radha; Smith, Rachel M; Park, Benjamin J; Jarvis, Joseph N; Govender, Nelesh P; et al. (2017). "Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 873–881. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8. PMC 5818156. PMID 28483415.

- ^ Guidelines for diagnosing, preventing and managing cryptococcal disease among adults, adolescents and children living with HIV. World Health Organization (WHO). 27 June 2022. ISBN 978-92-4-005217-8.

- ^ Martínez E, García-Viejo MA, Marcos MA, et al. (2000). "Discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis for cryptococcal meningitis in HIV-infected patients responding to highly active antiretroviral therapy". AIDS. 14 (16): 2615–26. doi:10.1097/00002030-200011100-00029. PMID 11101078.

- ^ a b Diehl, Camila; Pinzan, Camila; Alves de Castro, Patrícia; Delbaje, Endrews; García Carnero, Laura; Sánchez-León, Eddy; Bhalla, Kabir; Kronstad, James; Kim, Dong-gyu; Doering, Tamara; Alkhazraji, Sondus; Misha, Nagendra; Idrahin, Ashraf; Yoshimura, Mami; Goldman, Gustavo (25 June 2024). "Brilacidin, a novel antifungal agent against Cryptococcus neoformans". mBio. 15 (2): e01031-24. doi:10.1128/mbio.01031-24. PMC 11253610. PMID 38916308.

- ^ Mpairwe Y, Patel KM (1970). "Cryptococcal meningitis in Mulago Hospital, Kampala". East Afr Med J. 47 (8): 445–7. PMID 5479794.

- ^ "New guidelines from WHO recommend a simpler, safer treatment for cryptococcal disease in people living with HIV".

- ^ CF Schaars; Meintjes GA; Morroni C; et al. (2006). "Outcome of AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis initially treated with 200 mg/day or 400 mg/day of fluconazole". BMC Infect Dis. 6: 118. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-6-118. hdl:11427/14193. PMC 1540428. PMID 16846523.

- ^ Longley N, Muzoora C, Taseera K, Mwesigye J, Rwebembera J, Chakera A, Wall E, Andia I, Jaffar S, Harrison TS (2008). "Dose response effect of high-dose fluconazole for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in southwestern Uganda". Clin Infect Dis. 47 (12): 1556–61. doi:10.1086/593194. PMID 18990067.

- ^ Rajasingham R, Rolfes MA, Birkenkamp KE, Meya DB, Boulware DR (2012). "Cryptococcal meningitis treatment strategies in resource-limited settings: a cost-effectiveness analysis". PLOS Med. 9 (9): e1001316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001316. PMC 3463510. PMID 23055838.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cryptococcus neoformans at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cryptococcus neoformans at Wikimedia Commons- A good overview of Cryptococcus neoformans biology from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Cryptococcus neoformans biology, general information, life cycle image at MetaPathogen

- The outcome of Cryptococcus neoformans intracellular pathogenesis in human monocytes