Pinkerton (album)

| Pinkerton | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | September 24, 1996 | |||

| Recorded | August 22, 1995 – late July 1996[1] | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 34:36 | |||

| Label | DGC | |||

| Producer | Weezer | |||

| Weezer chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Pinkerton | ||||

| ||||

Pinkerton is the second studio album by the American rock band Weezer, released on September 24, 1996, by DGC Records. The guitarist and vocalist Rivers Cuomo wrote most of Pinkerton while studying at Harvard University, after abandoning plans for a rock opera, Songs from the Black Hole. It was the last Weezer album to feature the bassist Matt Sharp, who left in 1998.

To better capture their live sound, Weezer self-produced Pinkerton, creating a darker, more abrasive album than their self-titled 1994 debut. Cuomo's lyrics express loneliness and disillusionment with the rock lifestyle. The title comes from the character BF Pinkerton from Giacomo Puccini's 1904 opera Madama Butterfly, whom Cuomo described as an "asshole American sailor similar to a touring rock star". Like the opera, the album contains references to Japanese culture.

Pinkerton produced the singles "El Scorcho" and "The Good Life". It debuted at number 19 on the US Billboard 200, failing to meet sales expectations. It received mixed reviews; Rolling Stone readers voted it the third-worst album of 1996. For subsequent albums, Cuomo returned to more traditional pop songwriting and less personal lyrics.

In subsequent years, Pinkerton was reassessed and achieved acclaim. Several publications named it one of the best albums of the 1990s, and it was certified platinum in the US in 2016. Several emo bands have credited it as an influence.

Background

[edit]

In 1994, after the multi-platinum success of Weezer's self-titled debut album (also known as the Blue Album), Weezer took a break from touring for Christmas.[2] The singer and songwriter, Rivers Cuomo, felt limited by rock music. Every night, after performing with Weezer, he listened to Giacomo Puccini's 1904 opera Madama Butterfly; the "depth of emotion and sadness and tragedy" inspired him to go further with his music.[3]

In his home state of Connecticut, Cuomo began preparing material for Weezer's next album using an 8-track recorder.[4] His original concept was a rock opera, Songs from the Black Hole, that would express his mixed feelings about success.[4] Weezer developed Songs from the Black Hole through intermittent recording sessions throughout 1995.[5]

On April 14, 1995, Cuomo, who was born with one leg shorter than the other, had extensive leg surgery to lengthen his right leg, followed by weeks of painful physical therapy. This affected his songwriting, as he would spend long periods hospitalized, unable to walk without the use of a cane, and under the influence of painkillers.[6]

In the same period, Cuomo applied to study classical composition at Harvard University with a letter describing his disillusionment with the rock lifestyle: "You will meet two hundred people every night, but each conversation will generally last approximately thirty seconds ... Then you will be alone again, in your motel room. Or you will be on your bus, in your little space, trying to kill the nine hours it takes to get to the next city, whichever city it is."[7]

By May 1996, Cuomo's songwriting had become "darker, more visceral and exposed, less playful", and the Songs from the Black Hole concept was abandoned.[8] Weezer's second album would instead feature songs written while Cuomo was at Harvard, chronicling his loneliness and frustration, or what Cuomo referred to as his "dark side".[4][9]

Recording

[edit]In 1995, shortly before Cuomo left to study at Harvard, Weezer spent two weeks at New York City's Electric Lady Studios, where they had recorded their debut, and tracked the songs "Why Bother?", "Getchoo", "No Other One" and "Tired of Sex".[10][11] Weezer hoped to explore "deeper, darker, more experimental stuff"[11] and better capture their live sound.[12] They decided against hiring a producer, feeling that "the best way for us to sound like ourselves is to record on our own".[13] To give the album a live, "raw" feel, Cuomo, the guitarist Brian Bell and the bassist, Matt Sharp, recorded their vocals in tandem around three microphones rather than overdubbing them separately.[14]

While Cuomo was at Harvard, other Weezer members worked on side projects.[15] Sharp promoted Return of the Rentals, the debut album by his band the Rentals,[15] and Bell and the drummer, Patrick Wilson, worked on material for their bands the Space Twins and the Special Goodness.[10][15] In January 1996, during Cuomo's winter break, Weezer regrouped for a two-week session at Sound City Studios in Van Nuys, Los Angeles, to complete the songs they had worked on in August.[16] The Weezer collaborator Karl Koch said Sound City was "a significant part of the sound".[17]

After recording "El Scorcho" and "Pink Triangle", they separated while Cuomo returned to Harvard.[16] During Cuomo's 1996 spring break, Weezer regrouped at Sound City Studios and recorded "The Good Life", "Across the Sea" and "Falling for You" before Cuomo returned to Harvard for his finals.[18] They completed Pinkerton in mid-1996 in Los Angeles. Two additional tracks, "I Swear It's True" and "Getting Up and Leaving", were abandoned prior to mixing.[19]

Music and lyrics

[edit]There are some lyrics on the album that you might think are mean or sexist. I will feel genuinely bad if anyone feels hurt by my lyrics but I really wanted these songs to be an exploration of my "dark side"—all the parts of myself that I was either afraid or embarrassed to think about before. So there's some pretty nasty stuff on there. You may be more willing to forgive the lyrics if you see them as passing low points in a larger story. And this album really is a story: the story of the last 2 years of my life. And as you're probably well aware, these have been two very weird years.

– Rivers Cuomo's letter to the Weezer fan club, two months before the release of Pinkerton[17]

Pinkerton features a darker, more abrasive sound than Weezer's debut.[20][21] Critics described it as alternative rock,[22][23] emo,[24][25] power pop,[26] pop-punk,[20][27] indie rock,[28] and lo-fi.[29] Writing from a more direct and personal perspective,[30] Cuomo wrote of his dysfunctional relationships, sexual frustration, and struggles with identity.[14][31][32][33][34] The album charts his "cycle between 'lame-o and partier'".[35]

At just under 35 minutes, Pinkerton is, according to Cuomo, "short by design".[14] The first song, "Tired of Sex", written before the release of the Blue Album,[36] has Cuomo describing meaningless sex with groupies and wondering why true love eludes him.[14] "Across the Sea" was inspired by a letter Cuomo received from a Japanese fan: "When I got the letter, I fell in love with her ... I was very lonely at the time, but at the same time I was very depressed that I would never meet her."[33]

"The Good Life" chronicles the rebirth of Cuomo after an identity crisis as an Ivy League loner. Cuomo, who felt isolated at Harvard, wrote it after "becoming frustrated with that hermit's life I was leading, the ascetic life. And I think I was starting to become frustrated with my whole dream about purifying myself and trying to live like a monk or an intellectual and going to school and holding out for this perfect, ideal woman. And so I wrote the song. And I started to turn around and come back the other way."[32][33]

"El Scorcho" addresses Cuomo's shyness and inability to approach a woman while at Harvard; he explained that the song "is more about me, because at that point I hadn't even talked to the girl, I didn't really know much about her."[33] "Pink Triangle" describes a man who falls in love, but discovers the object of his devotion is a lesbian.[34]

Pinkerton is named after the character BF Pinkerton from Madama Butterfly, who marries and then abandons a Japanese woman named Butterfly.[37] Calling him an "asshole American sailor similar to a touring rock star", Cuomo felt the character was "the perfect symbol for the part of myself that I am trying to come to terms with on this album".[1] Other titles considered included Playboy and Diving into the Wreck (after the poem by Adrienne Rich).[1]

Like Madama Butterfly, Pinkerton views Japanese culture from the perspective of an outsider who considers Japan fragile and sensual;[38] the Japanese allusions are infused with the narrator's romantic disappointments and sexual frustration.[21] Cuomo wrote that Pinkerton "is really the clash of East vs West. My hindu, zen, kyokushin [karate], self-denial, self-abnegation, no-emotion, cool-faced side versus my Italian-American heavy metal side."[39] The songs are mostly sequenced in the order in which he wrote them, and so "the album kind of tells the story of my struggle with my inner Pinkerton".[40]

Artwork

[edit]

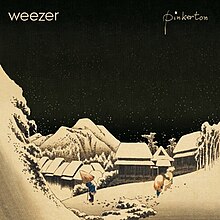

The cover artwork is derived from Kambara yoru no yuki ("Night snow at Kambara") from the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hiroshige's 1830s series 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō.[41] Lyrics from Madama Butterfly are printed on the Pinkerton CD in their original Italian: "Everywhere in the world, the roving Yankee takes his pleasure and his profit, indifferent to all risks. He drops anchor at random..."[42]

Behind the CD tray is a map with the title Isola della farfalla e penisola di cane (Italian for "Island of the Butterfly and Peninsula of Dog").[42] On the map are a ship named USS Pinkerton and "Mykel and Carli Island", alluding to Weezer's fan club founders, and the names of some of Cuomo's influences, including Howard Stern, Yngwie Malmsteen, Brian Wilson, Lou Barlow, Joe Matt, Camille Paglia and Ace Frehley.[42][43][44]

Release and promotion

[edit]Todd Sullivan, an A&R representative from Weezer's record label, Geffen, described Pinkerton as a "very brave record", but worried: "What sort of light does this put the band in? It could have been interpreted as them being a disposable pop band."[34] Geffen was pleased with the record and felt that fans would not be disappointed.[34]

Weezer turned down a video treatment for the lead single, "El Scorcho", proposed by Spike Jonze, who had helped raise Weezer's status with his videos for "Undone – The Sweater Song" and "Buddy Holly". Cuomo said: "I really want the songs to come across untainted this time around… I really want to communicate my feelings directly and because I was so careful in writing that way. I'd hate for the video to kinda misrepresent the song, or exaggerate certain aspects."[30] The "El Scorcho" video features Weezer playing in an assembly hall in Los Angeles, surrounded by light fixtures flashing in time to the music.[33] The director, Mark Romanek, quit after arguments with Cuomo, leaving Cuomo to edit the video himself.[45] The video debuted on MTV's 120 Minutes and received moderate airplay.[30]

Pinkerton debuted at number 19 on the US Billboard 200 chart, its highest position. It sold 47,000 copies its first week,[46][47] falling far short of the sales of Weezer's first album.[48] The singles also fared poorly; "El Scorcho" reached number 19, "The Good Life" reached number 32, and "Pink Triangle" did not chart.[17] As Pinkerton was not meeting sales expectations, Weezer felt pressure to make another music video more to the liking of MTV.[49] The video for "The Good Life", directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, stars Mary Lynn Rajskub as a pizza delivery girl, and uses simultaneous camera angles appearing on screen as a fractured full image.[49] Geffen rush-released the video to try to save the album, but was not successful.[50]

Tour

[edit]In October 1996, Weezer toured Australia, New Zealand and Japan.[51] Afterwards, they flew home to Los Angeles, where Wilson and Sharp made a promotional appearance on the nationally syndicated radio show Modern Rock Live.[51] On November 1, Weezer began a tour of North America at the Ventura Theatre in Ventura, California.[51] On November 6, they performed an acoustic set at Shorecrest High School in Seattle due to a contest won by a student.[50]

Weezer continued to tour until mid-1997.[52] The tour was postponed when the sisters Mykel, Carli and Trysta Allan died in a car accident while driving home from a Weezer show in Denver, Colorado.[53] Mykel and Carli ran Weezer's fan club and helped manage publicity for several other Los Angeles bands, and had inspired the Weezer song "Mykel and Carli". Weezer canceled a show to attend their funeral.[54] In August, Weezer and other bands held a benefit concert for their family in Los Angeles.[55]

Pinkerton's Inc. lawsuit

[edit]A day before Pinkerton was to be released on September 24, 1996, a restraining order was obtained by Californian security firm Pinkerton's Inc. Pinkerton sued Weezer and Geffen for federal trademark infringement, claiming they were trying to capitalize on their reputation.[56] Under the terms of the restraining order, which had Pinkerton's Inc seeking two million dollars in damages, Weezer would be kept from "selling, distributing, or advertising" an album under the name Pinkerton.[57] The Geffen spokesman Dennis Dennehy defended the title, arguing that it was a reference to Madama Butterfly and not aimed at "any sort of corporate entity".[58] Cuomo wrote a six-page paper explaining why he chose the title and why he felt it was essential.[59] The case was thrown out of court after the judge determined that "the hardship of not issuing the Pinkerton disc would be greater for Geffen than any hardship Pinkerton's Inc or its shareholders might incur from consumers who mistakenly presume the company has anything to do with the album".[59]

Critical reception

[edit]| Initial reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B[61] |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 7/10[64] |

| Pitchfork | 7.5/10[65] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Select | 3/5[68] |

| Spin | 7/10[69] |

Initial reviews of Pinkerton were mixed.[70][71] Jeff Gordinier of Entertainment Weekly deemed it "a collection of get-down party anthems for agoraphobics" and criticized Weezer's choice to self-produce, which he felt resulted in a "sloppy and raw" aesthetic inferior to the pop sound of their debut.[61] In Rolling Stone, Rob O'Connor called Cuomo's songwriting "juvenile", and singled out "Tired of Sex" as "aimless". However, he praised "Butterfly" as "a real treat, a gentle acoustic number that recalls the vintage, heartbreaking beauty of Big Star … suggesting that underneath the geeky teenager pose is an artist well on his way to maturity".[67] Rolling Stone readers voted the album the third-worst of 1996.[72] Some listeners were perturbed by the sexual nature of the lyrics;[17] Melody Maker's Jennifer Nine praised the music, but advised listeners "to ignore the lyrics entirely".[73]

Steve Appleford of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Pinkerton's songs often "are sloppy and awkward, but express a seemingly genuine, desperate search for sex and love".[63] Mark Beaumont of NME praised the album, writing that "by the time the affecting acoustic lament 'Butterfly' wafts in like Big Star at a wildlife protection meeting, Pinkerton starts feeling like a truly moving album".[64] Ryan Schreiber of Pitchfork wrote that "Pinkerton might actually be a bit much for fans who were wooed with the clean production and immediately accessible sound of these guys' debut, but if given a chance, it might surprise even some anti-Weezer folk".[65] The Guardian critic Kathy Sweeney found Pinkerton "noisier and messier than their last album, and all the better for it".[62] In another positive review, Dave Henderson of Q said that "on every tale of romance, delivered in perfect verse/chorus formula, you can see Jennifer Aniston giving it some attitude in the kitchen".[66]

Legacy

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 100/100 (deluxe edition)[74] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| American Songwriter | |

| Consequence of Sound | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[24] |

| Kerrang! | 5/5[77] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[78] |

| PopMatters | 10/10[79] |

| Record Collector | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Cuomo was embarrassed by Pinkerton's reception and the personal nature of its songs. According to the Guardian, "For a long time, Cuomo talked about Pinkerton like it was his high school diary, a humiliating reminder of a time when he was unapologetically emotional and corny."[83] In August 1997, Cuomo wrote in his diaries: "This has been a tough year. It's not just that the world has said Pinkerton isn't worth a shit, but that the Blue album wasn't either. It was a fluke ... I'm a shitty songwriter."[84]

After the Pinkerton tour, Sharp left the band and Weezer went on a hiatus.[17] In the following years, Pinkerton amassed a cult following through internet word of mouth.[85][86] A wave of mainstream emo bands including Jimmy Eat World, Saves the Day, Dashboard Confessional and Motion City Soundtrack began citing it as an influence.[17] Cuomo was initially uncomfortable with the development, and told Rolling Stone in 2001: "The most painful thing in my life these days is the cult around Pinkerton. It's just a sick album, sick in a diseased sort of way."[17] He told Entertainment Weekly:

It's a hideous record... It was such a hugely painful mistake that happened in front of hundreds of thousands of people and continues to happen on a grander and grander scale and just won't go away. It's like getting really drunk at a party and spilling your guts in front of everyone and feeling incredibly great and cathartic about it, and then waking up the next morning and realizing what a complete fool you made of yourself.[87]

Also in 2001, Cuomo mentioned to David Geffen, the head of Geffen Records, that Pinkerton had "turned into a real phenomenon". Geffen responded that "cult phenomenon" was euphemism for failure.[88] For Weezer's subsequent albums, Cuomo moved to simpler songwriting with less personal lyrics.[89] Rolling Stone described Weezer's followup, the Green Album (2001), as the "anti-Pinkerton", with album art and "squeaky-clean" production that recalled Weezer's debut.[17] Sharp sued Weezer in 2001 for songwriting royalties including songs from Pinkerton.[83]

Pinkerton's critical standing continued to rise,[85][86] and it came to be considered among Weezer's best work by fans and critics.[20][90] In 2002, Rolling Stone readers voted it the 16th-greatest album of all time.[91] In 2003, Pitchfork gave Pinkerton a perfect score and named it the 53rd-greatest album of the 1990s.[92] In 2004, Rolling Stone gave it a new review, awarding it five out of five and adding it to the Rolling Stone Hall of Fame.[81] Over the following years, it appeared in best-of lists by publications including Spin[93] and Drowned in Sound.[94] By August 2009, Pinkerton had sold 852,000 copies in the US[95] and was certified gold.[96] In 2016, almost 20 years after its release, Pinkerton was certified platinum for sales of over one million copies in the US.[97] That year, Alana Levinson of the Guardian wrote that Pinkerton's "conversational, confessional" lyrics were appropriate in the age of social media.[83]

By 2008, Cuomo had reconsidered the album, saying: "Pinkerton's great. It's super-deep, brave, and authentic. Listening to it, I can tell that I was really going for it when I wrote and recorded a lot of those songs."[98] In 2010, Bell told The Aquarian Weekly: "Pinkerton has definitely taken on a life of its own and became more successful and more accepted … As an artist, you just have to do what you believe in at the time, whether it's accepted or not. You just have to keep going with it."[99] That year, Weezer embarked on the Memories Tour, playing Blue and Pinkerton in their entirety.[100] Cuomo said of the tour: "The last time we played all of those [Pinkerton] songs, they went over like a lead balloon. And I just remember that feeling of just total rejection. And then to see 5,500 people singing along to every last word through every song on the album, even the really difficult ones, was incredibly validating for me."[100]

Accolades

[edit]| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin | United States | 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005[93] | 2005 | 61 |

| Pitchfork | United States | Top 100 Albums of the 1990s[92] | 2003 | 53 |

| Guitar World | Top 100 Guitar Albums of All-Time[101] | 2005 | 76 | |

| Rolling Stone | 100 Greatest Albums of the '90s[102] | 2010 | 48 | |

| Alternative Press | 20 Albums From 1996 That Mark Some of the Best of the Decade[103] | 2021 | N/A | |

| NME | United Kingdom | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[104] | 2013 | 108 |

Further releases

[edit]On November 2, 2010, DGC reissued Pinkerton with live performances, B-sides, and previously unreleased songs.[105] The reissue debuted at number six on the Billboard Catalog Albums chart[106] and achieved a perfect score on the aggregate review website Metacritic.[107]

In 2011, Cuomo published a book, The Pinkerton Diaries, which collects his writings from the era, including lyrics, studio notes, journals, emails, letters, and essays.[108] It was sold with the compilation album Alone III: The Pinkerton Years, compiling demos recorded between 1993 and 1996, when Cuomo was writing material for Pinkerton and Songs from the Black Hole.[108]

In May 2016, Pinkerton was reissued on vinyl by the record subscription service Vinyl Me, Please. The album was pressed on "dark blue translucent vinyl with black marbling" and was packaged in a custom sleeve with pop-out art, a custom lyric sheet, artwork by the Japanese painter Fuco Ueda, and a sake cocktail recipe.[109]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Rivers Cuomo.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Tired of Sex" | 3:01 |

| 2. | "Getchoo" | 2:52 |

| 3. | "No Other One" | 3:01 |

| 4. | "Why Bother?" | 2:08 |

| 5. | "Across the Sea" | 4:32 |

| 6. | "The Good Life" | 4:17 |

| 7. | "El Scorcho" | 4:03 |

| 8. | "Pink Triangle" | 3:58 |

| 9. | "Falling for You" | 3:47 |

| 10. | "Butterfly" | 2:53 |

| Total length: | 34:36 | |

Personnel

[edit]Adapted from the liner notes.[42][110]

Weezer

- Rivers Cuomo – vocals, guitar, keyboards, glockenspiel, clarinet, production

- Patrick Wilson – drums, production

- Brian Bell – guitar, vocals, production

- Matt Sharp – bass, vocals, production

Additional musicians

- Karl Koch – percussion on "Butterfly"

Technical personnel

- Joe Barresi – engineer

- Billy Bowers – engineer

- Jim Champagne – engineer

- David Dominguez – engineer

- Greg Fidelman – engineer

- Dave Fridmann – engineer

- Hiroshige – cover art

- Rob Jacobs – engineer

- Spike Jonze – photography

- Adam Kasper – engineer

- Karl Koch – webmaster

- George Marino – mastering

- Dan McLaughlin – engineer

- Shawn Everett – engineer, mixer

- Clif Norrell – engineer

- Jack Joseph Puig – engineer, mixing

- Jim Rondinelli – engineer

- Janet Wolsborn – art assistant

- Tod Sullivan – A&R

Charts

[edit]Weekly charts

[edit]| Chart (1996) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[111] | 38 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[112] | 41 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[113] | 15 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[114] | 94 |

| Finnish Albums (Suomen virallinen lista)[115] | 35 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[116] | 65 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[117] | 11 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[118] | 18 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[119] | 4 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[120] | 43 |

| US Billboard 200[121] | 19 |

Year-end charts

[edit]| Chart (2002) | Position |

|---|---|

| Canadian Alternative Albums (Nielsen SoundScan)[122] | 137 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[123] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[124] | Silver | 60,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[125] | Platinum | 1,000,000‡ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cuomo 2011.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Cohen, Ian (February 9, 2015). "Rivers Cuomo". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Weezer Record History Page 7". weezer.com. March 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 139.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Cuomo 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Pinkerton Deluxe liner notes

- ^ Cuomo 2011, p. 170.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 158.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 191.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d Luerssen 2004, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Luerssen 2004, p. 159.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Braun, Laura Marie (September 23, 2016). "How Weezer's Pinkerton went from embarrassing to essential". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media LLC. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 187.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Pinkerton – Weezer". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ a b "Tiny Mix Tapes Reviews: Weezer – Pinkerton". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Highfill, Samantha (November 2, 2010). "Weezer's 'Pinkerton' reissue: Read the 2001 EW story where Rivers Cuomo called the now-classic album a 'hugely painful mistake'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ "10 Essential '90s Alt-Rock Albums". Treble. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Vozick-Levinson, Simon (November 3, 2010). "Pinkerton: Deluxe Edition Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Montgomery, James. "mtv.com: Weezer Are the Most Important Band of the Last 10 Years". MTV. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "Revisiting Weezer's emotional cult classic: 'Pinkerton'". faroutmagazine.co.uk. September 24, 2021. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ MacKay, Emily (November 12, 2010). "Sacred Cows – Weezer's 'Pinkerton' Is Not A Masterpiece, It's Creepy". NME. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ "The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. September 28, 2022. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Redrup, Zach (November 8, 2010). "ALBUM: Weezer – Pinkerton (Reissue)". Dead Press!. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Luerssen 2004, p. 202.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 193.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d e Luerssen 2004, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Luerssen 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Edwars, Gavin. Rivers' Edge. Details Magazine, 1997, Volume 15, number nine.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 105.

- ^ Latimer, Lori. "Weezer: Pinkerton". Ink Blot Magazine. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "Reviews Madame Butterfly". japanreview.net. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Cuomo 2011, p. 158.

- ^ "The =W= Story". home.pacbell.net. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "Hiroshige / Evening Snow at Kambara (Kambara yoru no yuki), no. 16 from the Series Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido (Tokaido gosantsugi no uchi) / 1832 – 1833". daviddrumsey.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Pinkerton (Media notes). Weezer. DGC Records. 1996.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Howard Stern.com". Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 200.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ Partridge, Kenneth. "Weezer's 'Pinkerton' Turns 20: Why the Landmark, Raw Album Wasn't a Big Hit for the Band". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "For The Statistically Minded". Glorious Noise. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 221.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Luerssen 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 223.

- ^ Runtagh, Jordan (May 10, 2019). "Weezer's Blue Album: 10 Things You Didn't Know". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 25, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Kleinedler, Clare. "Weezer Mourns Tragic Deaths Of Fan Club Leaders". MTV News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Archive-Clare-Kleinedler. "Hundreds Join Weezer In Tribute To Fanclub Leaders". MTV News. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 203.

- ^ Andrade, Dereck (September 24, 1996). "Pinkerton obtains temporary restraining order against major U.S. record company; suit alleges trademark infringement by Los Angeles-based Geffen Records". Business Wire. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 204.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 205.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (October 25, 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton (DGC)". Chicago Tribune. sec. 7, p. 22. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Gordinier, Jeff (September 27, 1996). "Sugar Bare: Weezer's 'Pinkerton' Could Use The Sweet Relief of Their Debut". Entertainment Weekly. No. 346. p. 78. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Sweeney, Kathy (October 4, 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton (Geffen)". The Guardian. "Friday Review" section, p. 19.

- ^ a b Appleford, Steve (November 6, 1996). "Weezer, 'Pinkerton,' DGC". Los Angeles Times. "Calendar" section, p. F4. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Beaumont, Mark (September 28, 1996). "Weezer – Pinkerton". NME. p. 57. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Schreiber, Ryan (September 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Henderson, Dave (November 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Q. No. 122. p. 138.

- ^ a b O'Connor, Rob (October 31, 1996). Fricke, David (ed.). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Rolling Stone. No. 746. p. 66. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2005.

- ^ Morris, Gina (November 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Select. No. 77. p. 111.

- ^ Berrett, Jesse (November 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Spin. Vol. 12, no. 8. pp. 120–121. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "Pinkerton". Tower Records. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 206.

- ^ Luerssen 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Nine, Jennifer (October 5, 1996). "Weezer: Pinkerton". Melody Maker. p. 52.

- ^ "Pinkerton (Deluxe Edition) by Weezer Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Gold, Adam (December 15, 2010). "Weezer: Pinkerton [Deluxe Edition]". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ Gerber, Justin (November 2, 2010). "Album Review: Weezer – Pinkerton [Deluxe Edition]". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ "Weezer: Pinkerton". Kerrang!. November 6, 2010. p. 51.

- ^ Cohen, Ian (November 3, 2010). "Weezer: Pinkerton [Deluxe Edition] / Death to False Metal". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Sawdey, Evan (November 11, 2010). "Weezer: Pinkerton (Deluxe Edition)". PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Pearlman, Mischa (January 2011). "Weezer – Pinkerton: Deluxe Edition". Record Collector. No. 384. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Edwards, Gavin (December 9, 2004). "The Rolling Stone Hall of Fame — Weezer: Pinkerton". Rolling Stone. No. 963. p. 185. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2006.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "Weezer". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 865–66. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b c Levinson, Alana (September 24, 2016). "Weezer's Pinkerton and the invention of the manic pixie dream boys". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ Cuomo 2011, p. 232.

- ^ a b Ramirez, Ramon. "5 more college rock albums for your inner indie snob". The Daily Texan. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Luerssen 2004, p. 307.

- ^ Brunner, Rob (May 25, 2001). "Older & Weezer". Entertainment Weekly. No. 597. pp. 40–43. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (March 25, 2024). "Weezer's Blue Album at 30: The inside story of the debut that launched L.A.'s nerdiest band". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ Reisman, Abe J. (April 26, 2006). "Rivers' End: The Director's Cut". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Donohue, Mark. "Weezer: Pinkerton". Nude as the News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ "2002 Rolling Stone Readers' 100". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Mitchum, Rob (November 17, 2003). "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s: 053: Weezer Pinkerton". Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ a b "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Spin. 21 (7): 87. July 2005. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ Adams, Sean. "Drowned in Sound — Reviews — Weezer — Pinkerton". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Ayers, Michael D. (August 21, 2009). "Weezer Filled With 'Raditude' This Fall". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Crock, Jason (January 28, 2008). "Interview: Rivers Cuomo". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ^ "Interview with Weezer: They Want You To | The Aquarian Weekly". Theaquarian.com. April 29, 2010. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Elias, Matt (December 13, 2010). "Weezer's Rivers Cuomo reflects on Memories Tour, plans more shows in 2011". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ "Top 100 Guitar Albums of All-Time". Guitar World. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ "100 Best Albums of the '90s". Rolling Stone. October 4, 2019. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Penn, Vinnie (January 22, 2021). "20 albums from 1996 that mark some of the best of the decade". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Barker, Emily (October 25, 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 200–101". NME. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ "Weezer Reveal Pinkerton Reissue Details | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. September 27, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Pinkerton – Weezer". Billboard. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ^ "Reviews for Pinkerton (Deluxe Edition) by Weezer". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Pelly, Jenn (November 11, 2011). "Rivers Cuomo releasing Pinkerton Diaries book and demos comp Alone III". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "Weezer's new Pinkerton reissue comes with a sake cocktail recipe". Pitchfork. April 27, 2016. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Pinkerton (liner notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 2016. B0025153-01.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Australiancharts.com – Weezer – Pinkerton". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Weezer – Pinkerton" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 9827". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Weezer – Pinkerton" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Weezer: Pinkerton" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Weezer – Pinkerton" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Weezer – Pinkerton". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Weezer – Pinkerton". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Weezer – Pinkerton". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Weezer Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 2, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Weezer – Pinkerton". Music Canada. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "British album certifications – Weezer – Pinkerton". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "American album certifications – Weezer – Pinkerton". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Luerssen, John D. (2004). Rivers' Edge: The Weezer Story. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-619-3.

- Cuomo, Rivers (2011). The Pinkerton Diaries.