York Minster

| York Minster | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York | |

The southern façade of the cathedral, including the rose window on the south transept. | |

| 53°57′43″N 1°4′55″W / 53.96194°N 1.08194°W | |

| OS grid reference | SE 603 522 |

| Location | Deangate, York[1] |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic[citation needed] |

| Website | yorkminster |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Founded | 627 |

| Dedication | Saint Peter |

| Consecrated | 3 July 1472 |

| Associated people | William of York |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 14 June 1954[2] |

| Previous cathedrals | at least 3 |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Style | Early English, Perpendicular |

| Years built | c. 1230–1472 |

| Groundbreaking | 673 |

| Completed | 1472 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 524.5 feet (159.9 m)[3] |

| Nave length | 262 feet (80 m)[4] |

| Width | 222 feet (68 m)[3] |

| Nave width | 98 feet (30 m)[4] |

| Nave height | 99 feet (30 m)[3] |

| Choir height | 102 feet (31 m)[4] |

| Number of towers | 3 |

| Tower height | Central Tower: 235 feet (72 m)[3] Western Towers: 196 feet (60 m)[3] |

| Bells | 36 |

| Administration | |

| Province | York |

| Diocese | York (since 314) |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Stephen Cottrell |

| Dean | Dominic Barrington |

| Precentor | James Milne |

| Canon(s) | 1 vacancy |

| Canon Pastor | Timothy Goode |

| Canon Missioner | Maggie McLean |

| Archdeacon | Samantha Rushton |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Robert Sharpe |

| Business manager | David Colthup (Chapter Steward) |

| |

| Official name | York Minster cathedral precinct |

| Designated | 8 October 1937 |

| Reference no. | 1017777 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Cathedral Church of St Peter, York Minster |

| Designated | 14 June 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1257222 |

York Minster, formally the Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, is an Anglican cathedral in the city of York, North Yorkshire, England. The minster is the seat of the archbishop of York, the second-highest office of the Church of England, and is the mother church for the diocese of York and the province of York.[5] It is administered by its dean and chapter. The minster is a Grade I listed building and a scheduled monument.

The first record of a church on the site dates to 627; the title "minster" also dates to the Anglo-Saxon period, originally denoting a missionary teaching church and now an honorific.[6] The minster undercroft contains re-used fabric of c. 1160, but the bulk of the building was constructed between 1220 and 1472. It consists of Early English Gothic north and south transepts, a Decorated Gothic nave and chapter house, and a Perpendicular Gothic eastern arm and central tower.

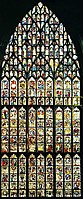

The minster retains most of its medieval stained glass, a significant survival among European churches.[7] The east window, which depicts the Last Judgment, is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the world. The north transept contains the Five Sisters window, which consists of five lancets, each over 53 feet (16.3 m) high, filled with grisaille glass.[8]

History

[edit]A bishop of York was summoned to the Council of Arles in 314, indicating the presence of a Christian community in York at this time; however, archaeological evidence of Christianity in Roman York is limited.[9][10] The first recorded church was a wooden structure built hurriedly in 627 to provide a place to baptise Edwin, King of Northumbria. The location of this church, and its pre-1080 successors, is unknown. It was probably in or beside the old Roman principia, (the military headquarters), which may have been used by the king when in residence in York. Archaeological evidence indicates the principia was located partly beneath the post-1080 Minister site, but excavations undertaken in 1967-73 found no remains of the pre-1080 churches. It can therefore be inferred that Edwin's church, and its immediate successors, was near the current Minster (possibly to the north, underneath the modern Dean's Park)[11] but not directly on the same site. [12]

Moves towards a more substantial building began shortly after Edwin's baptism. According to Bede, Edwin set about building a larger church made of stone, intended to enclose the wooden chapel in which he had been baptised.[13] This stone structure was completed in 637 by Oswald and was dedicated to Saint Peter. The church soon fell into disrepair and was dilapidated by 670 when Saint Wilfrid ascended to the See of York. He repaired and renewed the structure, installing leaded roofs, glass windows, and rich furnishings.[14] The attached school and library were established and by the 8th century were some of the most substantial in Northern Europe.[15][16]

In 741, the cathedral may have been damaged or destroyed in a fire.[17][18] Any damage to the cathedral was not long-lasting. Alcuin (who makes no mention of the fire or rebuilding) wrote in detail of the building's wealth and grandeur. In his time, there was a grand altar erected over the place of Edwin's baptism, covered with precious metals and jewels. A spectacular chandelier hung above the altar, and the cathedral possessed a rich and valuable silver cross and golden cruet.[17][19] The cathedral, together with the rest of the city, then passed through the hands of numerous invaders, and its history is obscure until the 10th century. There were a series of Benedictine archbishops, including Saint Oswald of Worcester, Wulfstan and Ealdred, who travelled to Westminster to crown William the Conqueror in 1066. Ealdred died in 1069 and was buried in the cathedral.[20]

In January 1069 a rebellion in support of Edgar Ætheling triggered a brutal crackdown by William. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that William's forces "ravaged the town, and made St Peter’s Minster a disgrace". Later in the year, Danish invaders supporting the Ætheling sailed up the Humber and Ouse; they attacked the city, in the course of which a fire broke out, burning the cathedral.[21] Anything at this point remaining of the cathedral may then have been further damaged by William's Harrying of the North. The first Norman archbishop, Thomas of Bayeux, arriving in 1070, apparently organised repairs, but in 1075, another Danish force sailed up the river, "travelled to York and broke into St Peter’s Minster, and there took much property, and so went away."[22] Building of a new cathedral, the Norman Minster, began in 1080, and was completed before Thomas's death in 1100.[22] The new cathedral was likely immediately to the south of the old Saxon cathedral, which was probably demolished once the new structure was completed.[11][23] Built in the Norman style, the new cathedral was 364.173 ft (111 m) long and rendered in white and red lines. The new structure was damaged by fire in 1137 but was soon repaired. The choir and crypt were remodelled in 1154, and a new chapel was built, all in the Norman style.

The Gothic style in cathedrals had arrived in the mid 12th century. Walter de Gray was made archbishop in 1215 and ordered the construction of a Gothic structure to rival Canterbury; building began in 1220. The north and south transepts were the first new structures; completed in the 1250s, both were built in the Early English Gothic style but had markedly different wall elevations. A substantial central tower was also completed, with a wooden spire. Building continued into the 15th century.

The Chapter House was begun in the 1260s and was completed before 1296. The wide nave was constructed from the 1280s on the Norman foundations. The outer roof was completed in the 1330s, but the vaulting was not finished until 1360. Construction then moved on to the eastern arm and chapels; the Norman choir was demolished in the 1390s with the exception of its undercroft of c. 1160, which was reconstructed to provide a platform for the new high altar.[7] Work here finished around 1405. In 1407 the central tower collapsed; the piers were then reinforced, and a new tower was built from 1420. The western towers were added between 1433 and 1472. The cathedral was declared complete and consecrated in 1472.[24]

The English Reformation led to the looting of much of the cathedral's treasures and the loss of much of the church lands. Under Elizabeth I there was a concerted effort to remove all traces of Roman Catholicism from the cathedral; there was much destruction of tombs, windows and altars. In the English Civil War the city was besieged and fell to the forces of Cromwell in 1644, but Thomas Fairfax prevented any further damage to the cathedral.

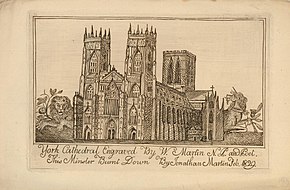

Following the easing of religious tensions some work was done to restore the cathedral. From 1730 to 1736 the whole floor of the minster was relaid in patterned marble and from 1802 there was a major restoration. However, on 2 February 1829, an arson attack by Jonathan Martin inflicted heavy damage on the east arm.[25] An accidental fire in 1840 left the nave, south west tower and south aisle roofless and blackened shells. The cathedral slumped deeply into debt and in the 1850s services were suspended. From 1858 Augustus Duncombe worked successfully to revive the cathedral. In 1866, there were six residentiary canonries: of which one was the Chancellor's, one the Sub-Dean's, and another annexed to the Archdeaconry of York.[26]

During the 20th century there was more concerted preservation work, especially following a 1967 survey that revealed the building, in particular the central tower, was close to collapse. £2,000,000 was raised and spent by 1972 to reinforce and strengthen the building foundations and roof. During the excavations that were carried out, remains of the north corner of the Roman Principia (headquarters of the Roman fort of Eboracum) were found under the south transept. This area, as well as remains of the Norman cathedral, re-opened to the public in spring 2013 as part of the new exhibition exploring the history of the building of York Minster.[27]

1984 fire

[edit]On 9 July 1984, York Minster suffered a serious fire in its south transept during the early morning hours.[28] Firefighters made a decision to deliberately collapse the roof of the south transept by pouring tens of thousands of gallons of water onto it, in order to save the rest of the building from destruction.[29] A total of 114 firefighters from across North Yorkshire responded to the fire and contained it,[28] while York Minster's staff and clergy rushed to preserve historical objects in the building.[28] The glass of the south transept rose window was shattered by the heat but the lead held it together, allowing it to be taken down for restoration.[30][29] A subsequent investigation found an 80% chance that the fire was caused by a lightning strike to a metal electrical box on top of the roof, a 10% chance that the fire was caused by arson, and a 10% chance that the fire was caused by an electrical fault.[28] Some traditionalist Anglicans suggested the fire was a sign of divine displeasure at the recent consecration as Bishop of Durham of David Jenkins, whose views they considered heterodox.[31]

A repair and restoration project was completed in 1988 at a cost of £2.25 million,[28] and included new roof bosses to designs which had won a competition put on by BBC Television's Blue Peter programme for children.[29] The roof trusses were rebuilt in oak, but some were coated with fire-retardant plaster.[28]

2002 West Door renewal

[edit]In 2002, the carvings round the great west door. which had become severely weathered, were replaced with new sculptures carved by Minster masons to designs by the sculptor Rory Young, telling the Genesis story.

2007–2018 renovation

[edit]In 2007 renovation began on the east front, including the Great East Window, at an estimated cost of £23 million.[32][33] The 311 glass panels from the Great East Window were removed in 2008 for conservation. The project was completed in 2018.[34]

Schools

[edit]There have been choir schools associated with the Minster since the 7th century. A 'song school' was founded in 627 by Paulinus of York, the first Archbishop of York.[35] Buildings used by the former Minster school have been awarded listed status, among them the school house built 1830–33,[36] two houses dating back to 1837,[37] and a Georgian building of 1755.[38]

Architecture of the present building

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

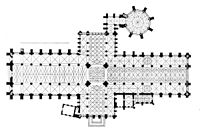

York Minster is the second-largest Gothic cathedral of Northern Europe and clearly charts the development of English Gothic architecture from Early English through to the Perpendicular Period. The present building was begun in about 1230 and completed in 1472. York Minster is the largest cathedral completed during the Gothic period of architecture, Cologne Cathedral only being completed in 1880, after being left uncompleted for 350 years. It has a cruciform plan with an octagonal chapter house attached to the north transept, a central tower and two towers at the west front. The stone used for the building is magnesian limestone, a creamy-white coloured rock that was quarried in nearby Tadcaster. The Minster is 524.5 feet (159.9 m) long[3] and the central tower has a height of 235 feet (72 m).[3] The choir has an interior height of 102 feet (31 m).[citation needed]

The north and south transepts were the first parts of the new church to be built. They have simple lancet windows, including the Five Sisters in the north transept. These are five lancets, each 16.3 metres (53 ft) tall and five feet wide[39] and glazed with grey (grisaille) glass,[40] rather than narrative scenes or symbolic motifs that are usually seen in medieval stained-glass windows. In the south transept is a rose window whose glass dates from about 1500 and commemorates the union of the royal houses of York and Lancaster. The roofs of the transepts are of wood; that of the south transept was burnt in the fire of 1984 and was replaced in the restoration work which was completed in 1988. New designs were used for the bosses, five of which were designed by winners of a competition organised by the BBC's Blue Peter television programme.

Work began on the chapter house and its vestibule that links it to the north transept after the transepts were completed. The style of the chapter house is of the early Decorated Period where geometric patterns were used in the tracery of the windows, which were wider than those of early styles. However, the work was completed before the appearance of the ogee curve, an S-shaped double curve that was extensively used at the end of this period. The windows cover almost all of the upper wall space, filling the chapter house with light. The chapter house is octagonal, as is the case in many cathedrals, but is notable in that it has no central column supporting the roof. The wooden roof, which was of an innovative design, is light enough to be able to be supported by the buttressed walls. The chapter house has many sculptured heads above the canopies, representing some of the finest Gothic sculpture in the country. There are human heads, no two alike, and some pulling faces; angels; animals and grotesques. Unique to the transepts and chapter house is the use of Purbeck marble to adorn the piers, adding to the richness of decoration. The chapter house exhibits the influence of Saint-Urbain, Troyes in the tracery in the vestibule, while the stalls are enlarged versions of the archivolt niches in the portal of Notre-Dame de Paris.[41]

The nave was built between 1291 and c. 1350 and is also in the decorated Gothic style. It is the widest Gothic nave in England and has a wooden roof (painted so as to appear like stone) and the aisles have vaulted stone roofs. At its west end is the Great West Window, known as the 'Heart of Yorkshire', second-largest among the church's 128 windows.[42] This window was designed and built along with the rest of the west front by the master mason Ivo de Raghton in 1338–39.[43] The tracery is in the Flamboyant or Curvilinear Decorated style of English Gothic architecture.[44][43][45] Because of deterioration of stone mullions, the tracery was replaced in the late 1980s with an exact copy.[44]

The east end of the Minster was built between 1361 and 1405 in the Perpendicular Gothic style. Despite the change in style, noticeable in details such as the tracery and capitals, the eastern arm preserves the pattern of the nave. The east end contains a four-bay choir; a second set of transepts, projecting only above half-height; and the Lady Chapel. The transepts are in line with the high altar and serve to throw light onto it. Behind the high altar is the Great East Window, the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the country, which underwent a decade-long restoration and conservation project, completed in 2018.

The sparsely decorated Central Tower was built between 1407 and 1472 and is also in the Perpendicular style. Below this, separating the choir from the crossing and nave is the striking 15th-century choir screen. It contains sculptures of the kings of England from William the Conqueror to Henry VI with stone and gilded canopies set against a red background. Above the screen is the organ, which dates from 1832. The West Towers, in contrast with the Central Tower, are heavily decorated and are topped with battlements and eight pinnacles each, again in the Perpendicular style.

In 2003, English Heritage made publicly available a monograph on the architectural history of York Minster.[46] The book charts the construction and development of the minster based on the architectural recording of the building from the 1970s.

-

The cruciform plan of York Minster; drawing by Georg Dehio.

-

The chapter house

-

The Kings Screen and organ

-

Crossing

-

Some of the 15 statues of kings, from Henry III to Henry VI, in the 15th-century Kings Screen

-

One of the towers, near sunset, York Minster

Stained glass

[edit]-

The west window (1338–39), with curvilinear tracery in the Decorated style

-

Detail from the east window, depicting the first two days of creation

-

The east window (1405–1408), in the Perpendicular style

-

Detail of a clerestory window, depicting part of a miracle of St Nicholas

-

The Five Sisters window, in the Early English style

Some of the stained glass in York Minster dates back to the 12th century and much of the glass (white or coloured) came from Germany.[47] The glass was painted, fired, then joined with lead strips (came) into the windows. The 77-foot (23 m) tall and 32-foot (9.8 m) wide[48] The Dean and Chapter of York commissioned John Thornton in 1405 to design the Great East Window;[49] he was paid £66 for the work.[50] This is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the country, according to the Minster.[51] The window represents scenes from the Book of Revelation, and the glazier Thornton may have been influenced by earlier illuminated manuscripts on the subject such as the Latin Douce Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce MS 180) and the Old French Queen Mary Apocalypse (London, British Library Royal MS BXV).[52] The work was conceived by Archbishop John of Thoresby in the mid fourteenth century, but the window itself was only completed thanks to the funding of Bishop Walter Skirlaw and Archbishop Richard Scrope.[52]

Another important window is the 53-foot (16.3 m)[8] tall Five Sisters window. Because of the extended time periods during which the glass was installed, different types of glazing and painting techniques are visible in the different windows. Approximately two million individual pieces of glass make up the cathedral's stained-glass windows. The windows were removed in 1916 because of the fear of bombing during the First World War and the "Five Sisters" window was restored in 1925 with £3,500 raised by Almyra Gray and Helen Little.[53] The glass was removed again during the Second World War.

In 2008 a conservation project of the Great East Window commenced, involving the removal, repainting and re-leading of each individual panel.[54] While the window was in storage in the minster's stonemasons' yard, a fire broke out in some adjoining offices, due to an electrical fault, on 30 December 2009.[55] The window's 311 panes, stored in a neighbouring room, were undamaged and were successfully moved to safety.[56][57] In September 2015, the first phase of the renovation project of the East Front of the Minster was completed.[58] The final phase of the £11 million restoration[59] of the 311 panels was completed in September 2017 and they were re-installed between November 2017 and January 2018. In total, the work on the Great East Window had taken 92,400 hours of labour, including the time required to add protective UV coating on the glass.[60] The work was largely undertaken or overseen by Peter Gibson, who worked on all the Minster's windows during his career.[61]

Towers and bells

[edit]

The two west towers of the minster hold bells, clock chimes and a concert carillon. The north-west tower contains Great Peter (216 cwt or 10.8 tons) and the six clock bells (the largest weighing just over 60 cwt or 3 tons). The south-west tower holds 14 bells (tenor 59 cwt or 3 tons) hung and rung for change ringing and 22 carillon bells (tenor 23 cwt or 1.2 tons) which are played from a baton keyboard in the ringing chamber (all together 36 bells.)

The clock bells ring every quarter of an hour during the daytime and Great Peter strikes the hour.

The change ringing bells fell silent in October 2016, following the controversial termination of the ringers' volunteer agreements by the dean and chapter.[62][63] The pause in ringing included the Christmas period of 2016, reported as the first time in over 600 years that the Minster's bells were not heard on Christmas Day.[64] After a year with no change ringing, a new band was appointed and ringing resumed.[65]

York Minster became the first cathedral in England to have a carillon of bells with the arrival of a further twenty-four small bells on 4 April 2008. These are added to the existing "Nelson Chime" which is chimed to announce Evensong around 5:00 pm each day, giving a carillon of 35 bells in total (three chromatic octaves). The new bells were cast at the Loughborough Bell Foundry of John Taylor & Co, where all of the existing minster bells were cast. The new carillon is a gift to the minster. It will be the first new carillon in the British Isles for 40 years and first hand played carillon in an English cathedral. Before Evensong each evening, hymn tunes are played on a baton keyboard connected with the bells, but occasionally anything from Beethoven to the Beatles may be heard.[66]

Shrines

[edit]When Thomas Becket was murdered and subsequently enshrined at Canterbury, York found itself with a rival major draw for pilgrims. More specifically, pilgrims spent money and would leave gifts for the support of the cathedral. Hence Walter de Gray, supported by the King, petitioned the Pope. On 18 March 1226, Pope Honorius issued a letter to the effect that the name of William (Fitzherbert), formerly Archbishop of York, was "inscribed in the catalogue of the Saints of the Church Militant." Thus there was now St William of York (whose name is perhaps more often associated with the adjacent St William's College). York had its saint but it took until 1279, when William de Wickwane (William de Wykewayne) was elected archbishop, for the remains of the canonised William to be transferred to a shrine prepared for them behind the high altar.[67] This was placed on a platform raised upon the arches of the crypt removed to this position for that purpose. On 29 December King Edward I himself, together with the bishops who were present, carried on their shoulder the chest or feretory containing the relics to their new resting-place and Anthony Beck, consecrated the same day as Bishop of Durham, paid all the expenses.

The tomb of Walter de Gray was erected in the south transept. His remains were interred on "the vigil of Pentecost, 1255"[67] under his effigy "in full canonicals" carved in Purbeck marble under a canopy resting on ten light pillars. It was subsequently somewhat hidden behind a screen of ironwork erected by Archbishop William Markham in the early 19th century.

On 9 November 2022 King Charles III unveiled a statue of his mother Queen Elizabeth II in a niche on the west facade of York Minster.[68]

Consulting architects

[edit]The Minster's consulting architects (since 1965 called "Surveyors of the Fabric" – see Cant and Aylmer, York Minster, p. 554) have included the following:

- G. E. Street (1868–1881)

- G. F. Bodley (1882–1907)

- Walter Tapper (1908–1935)

- Sir Charles Reed Peers (1935–1946)

- Sir Albert Edward Richardson (1946–1964)

- Bernard Feilden (1964–1977)

- Charles Brown (1977–1995)

- James Simpson c. 1995

- Andrew Arrol ( –2020)

- Oliver Caroe (2020– )

Vaults

[edit]-

Chancel

-

South transept

-

North transept

-

Chapter house

-

Nave

Organ

[edit]The fire of 1829 destroyed the organ and the basis of the present organ dates from 1832, when Elliot and Hill constructed a new instrument. This organ was reconstructed in 1859 by William Hill and Sons. The case remained intact, but the organ was mechanically new, retaining the largest pipes of the former instrument.

In 1903, J. W. Walker and Sons built a new instrument in the same case. They retained several registers from the previous instrument.

Some work was undertaken in 1918 by Harrison & Harrison when the Tuba Mirabilis was added and the Great chorus revised. The same firm rebuilt this Walker-Harrison instrument in 1931 when a new console and electro-pneumatic action were added together with four new stops. The smaller solo tubas were enclosed in the solo box. In 1960, J. W. Walker & Sons restored the actions, lowered wind pressures and introduced mutations and higher chorus work in the spirit of the neo-classical movement. They cleaned the organ in 1982.

The fire of 1984 affected the organ but not irreparably; the damage hastened the time for a major restoration, which was begun in 1991 and finished two years later by Principal Pipe Organs of York, under the direction of their founder, Geoffrey Coffin, who had at one time been assistant organist at the Minster.[69]

In 2018, a £2 million project to refurbish the current organ was announced. The project took two years for its completion in March 2021 and saw nearly all of its 5,403 pipes removed and taken to organ specialists Harrison & Harrison in Durham.[70][71]

-

The organ on the choir screen

-

The choir

-

The crypt

Organists

[edit]The organists of York Minster have had several official titles, the job description roughly equates to that of Organist and Master of the Choristers. The current Organist and Director of Music of the Minster is Robert Sharpe. There is also an assistant director of Music, Ben Morris.

Among the notable organists of York Minster are four members of the Camidge family, who served as the cathedral's organists for over 100 years, and a number of composers including John Naylor, T. Tertius Noble, Edward Bairstow, Francis Jackson, and Philip Moore.

Dean and chapter

[edit]As of 20th January 2024:

- Dean – Dominic Barrington (since 12 November 2022 installation)[72]

- Pastor – Timothy Goode (since 9 September 2023 installation)[73]

- Missioner – Maggie McLean (since 17 November 2019 installation)[74]

- Precentor – James Milne (since 18 May 2024 installation)[75]

- Chancellor – vacant since 31 August 2020[76]

Burials

[edit]

- Bosa of York, Bishop of York and Saint (died c. 705)

- Eanbald, Archbishop (780–796)

- Osbald, King of Northumbria (died 799)

- Guthred Hardacnutson, King of Northumbria (died 895)

- Tostig Godwinson, brother of King Harold II (both died in separate battles in 1066)

- Ealdred, Archbishop (1061–1069)

- Thomas of Bayeux, Archbishop (1070–1100)

- Gerard, Archbishop (1100–1108)

- Thomas II of York, Archbishop (1108–1114)

- William of York, Archbishop (1141–1147, 1153–1154)

- Henry Murdac, Archbishop (1147–1153)

- Roger de Pont L'Évêque, Archbishop (1154–1181)

- Walter de Gray, Archbishop (1216–1255)

- Sewal de Bovil, Dean and Archbishop (1256–1258)

- Godfrey Ludham, Archbishop (1258–1265)

- William Langton, Archbishop (1265)

- Walter Giffard, Archbishop (1266–1279)

- John le Romeyn, Archbishop (1286–1296)

- Henry of Newark, Archbishop (1296–1299)

- William Greenfield, Archbishop (1306–1315)

- William of Hatfield, infant son of Edward III (1337)

- William Melton, Archbishop (1317–1340)

- William Zouche, Archbishop (1342–1352)

- Henry Percy, soldier (1364–1403)

- Richard le Scrope, Archbishop (1398–1405)

- Henry Bowet, Archbishop (1407–1423)

- Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop (1480–1500)

- Thomas Savage, Archbishop (1501–1507)

- Hugh Ashton, Archdeacon of York (died 1522)

- John Piers, Archbishop (1589–1594)

- George Meriton, Dean of York (1579–1624)

- Thomas Danby (MP) (1610–1660)

- Richard Neile, Archbishop (1631–1640)

- Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, (1730–1782)

- John Farr Abbott, barrister (1756–1794)

Astronomical clock

[edit]The astronomical clock was installed in the north transept of York Minster in 1955. The clock is a memorial to the airmen operating from bases in Yorkshire, County Durham and Northumberland who were killed in action during the Second World War.[77] The clock is not currently working.

Illuminations

[edit]

In November 2002, York Minster was illuminated in colour, devised by York-born Mark Brayshaw, for the first time in its history. The occasion was televised live on the BBC1 Look North programme. Similar illuminations have been projected over the Christmas period in subsequent years.

York Minster was also artistically illuminated on 5 November 2005, celebrating the 400th anniversary of the foiling of York-born Guy Fawkes' gunpowder plot. This was done by Patrice Warrener using his unique "chromolithe" technique with which he 'paints' with light, picking out sculpted architectural details.

In October 2010, York Minster's south transept was selected for "Rose", a son et lumiere created by international artists Ross Ashton and Karen Monid which lit up the entire exterior of the south transept of the minster and illuminated the Rose Window. There were also satellite illuminate events in Dean's Park.

York Mystery Plays

[edit]In 2000, the Dean and Chapter allowed the York Mystery Plays to be performed for the first time inside the Minster, directed by Gregory Doran.[78] The Plays returned to the Minster for a second time in 2016, directed by Phillip Breen with Philip McGinley performing the role of Jesus.[79]

See also

[edit]- Archbishop's Palace, Bishopthorpe

- Early Gothic architecture

- English Gothic architecture

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- English Gothic stained glass windows

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

- Cathedral diagram

- Dean of York

- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

- The Minster School, York (now closed)

- Old Palace, York: Minster Library and Archives

- York Minster Police

References

[edit]- ^ "York Minster". York Minster. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Cathedral Church of St Peter, York Minster (1257222)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bigland, John (1815). Yorkshire; or, Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive of That County. London. p. 211. OCLC 19912009. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "York Minster". York Minster. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "York Minster a Medieval Cathedral" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ "York Minster FAQs". York Minster. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ a b Pesvner, Nikolaus; Metcalf, Priscilla (2005). The Cathedrals of England: The North and East Anglia. London: The Folio Society. pp. 294–95, 303.

- ^ a b "Work Minster Fact Sheets: The Five Sisters Window" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Tillott, P. M., ed. (1961). "Before the Norman Conquest". A History of the County of York: the City of York. London: Victoria County History. pp. 2–24. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019 – via British History Online.

- ^ Ottaway, Patrick (2004). Roman York. Tempus. pp. 136–138. ISBN 0-7524-2916-7.

- ^ a b "Character area 9: Minster Precinct - Archaeological background". www.york.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "One York or Several? The city resettled". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "One York or Several? The city resettled". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "One York or Several? The city resettled". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Blair, Peter Hunter (1990). The World of Bede (1970 reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0521398190.

- ^ The most renowned product of the school was Alcuin.

- ^ a b Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "One York or Several? The city resettled". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Evidence of the fire is limited to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the fragmentary Northern Annals. Of these, the Chronicle briefly reports, under year 741, "York was burnt down." The Annals give a little more detail, reporting that on 23 April 741 "the monasterium in the city of York was burnt." Academic opinion is divided on the severity of the fire, and on the identity of the affected monasterium. Besides St Peter's Cathedral, candidates might include the Church of St Gregory, the St Mary Bishophill churches, St Martin’s, and Holy Trinity, Micklegate. [1]

- ^ Alcuin: His Life and Legacy. James Clarke & Company Limited. 29 November 2012. ISBN 978-0-227-90083-3.

- ^ "Britannia Biographies: Ealdred, Archbishop of York". notesfromtheroad.net. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "French Conquest and Lordship". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ a b Palliser, D. M., ed. (2014). "French Conquest and Lordship". Medieval York: 600-1540. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-925584-9. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ A similar approach was taken in the same period at Winchester.[2]

- ^ "The Medieval Minster: History of York". www.historyofyork.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ "Jonathan Martin: The Man Who Burned York Minster". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ The Clergy List for 1866 (London: George Cox, 1866) p. 261

- ^ "Revealed". York Minster. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Potts, Lauren (9 July 2014). "Remembering the York Minster fire 30 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "1984: York Minster ablaze". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "York Minster Is Back to Life After '84 Fire". The New York Times. 5 November 1988. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "The Right Reverend David Jenkins: Bishop of Durham who created a storm for the Church but was admired within his diocese". The Daily Telegraph. No. 50,165. 5 September 2016. p. 25. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "York Minster: a very brief history". York Minster. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "York Minster Press Pack" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "York Minster window renovations complete after a decade". BBC News. 17 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "History". The Minster School. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Historic England (14 June 1954). "Minster Song School (Part), York (1257229)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Historic England (14 June 1954). "Minster Song School (Part), York (1257259)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Historic England (14 June 1954). "Minster Song School (Part), York (1257261)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "York Minster centre for school visits, York Minster fact sheets, the great west window" (PDF). York Minster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ James, Sara N. (2016). Art in England: The Saxons to the Tudors: 600–1600. Oxbow Books. p. 105. ISBN 9781785702235.

- ^ Wilson, Christopher (January 2008). "Not without Honour save in its own Country? Saint-Urbain at Troyes and its Contrasting French and English Posterities". Not without Honour save in its own Country? Saint-Urbain at Troyes and its Contrasting French and English Posterities | The Year 1300 and the Creation of a new European Architecture. Architectura Medii Aevi. Vol. 1. pp. 107–122. doi:10.1484/M.AMA-EB.3.9. ISBN 9782503522869.

- ^ Brown, Sarah (2018). Stained Glass at York Minster. Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Limited. ISBN 9781785510731. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Curl, James Stevens (2015). "Raghton, Ivo de". In Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (eds.). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b York Minster site: the Great West Window – Fact Sheet 7

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015). "Flamboyant". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Brown, S. (2003). "York Minster: An architectural history c. 1220–1500". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Peter (1979). The Stained and Painted Glass of York Minster. Norwich: Jarrold Publishing. pp. 5–6. ISBN 085306833X.

- ^ Berlow, Lawrence (2015). Reference Guide to Famous Engineering Landmarks of the World: Bridges, Tunnels, Dams, Roads and Other Structures. Routledge. ISBN 9781135932541. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brian Clarke. "The Great East Window: Brian Clarke". HENI Talks. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Preserving York Minster's Great East Window – 50th Anniversary, University of York". University of York. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Great East Window". York Minster. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ a b Brown, Sarah (2018). The great east window of York Minster : an English masterpiece. London: Third Millennium Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78125-978-8. OCLC 1023399752.

- ^ Fell, Alison S. (2018). Women as Veterans in Britain and France after the First World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-1-108-42576-6.

- ^ The ONE Show. 29 January 2008. BBC 1.

- ^ "York Minster Stoneyard blaze caused by electrical fault". York Press. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "York Minster fire: medieval stained-glass window saved". Daily Telegraph. London. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Fire crews rescue medieval York Minster window". BBC News Online. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ "York Minster window gets major renovation". BBC News. 30 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Medieval great window finally restored". BBC News. 22 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Daley, Jason (11 January 2018). "York Minister's Massive Medieval Stained-Glass Window Restored to Its Former Glory". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Tributes paid to Peter Gibson, renowned York craftsman and glazier" – The Press, 15 November 2016

- ^ "Bell ringers update". York Minster Society of Change Ringers. 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Perraudin, Frances (13 October 2016). "For whom the bell tolls: York Minster to fall silent as ringers sacked". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "York Minster bells' first Christmas Day silence for 600 years". BBC News. BBC. 26 December 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (22 August 2017). "York Minster bells to chime again next month after year's silence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Peacock, Alix (4 April 2008). "New Bells for York Minster". Minster News. York Minster. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ a b Purey-Cust, A. P. The Very Reverend Dean York Minster (1897) Isbister & Co

- ^ "York: King Charles unveils first statue of Queen since her death". BBC News. 9 November 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Yorkshire York, Cathedral of St. Peter ('York Minster'), Deangate [D04217]". National Pipe Organ Register. British Institute of Organ Studies. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "The once-a-century refurbishment". Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "York Minster Grand Organ to play again after £2m repair". BBC News. BBC. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "The Installation of Dominic Barrington as the 77th Dean of York". Archbishop of York. 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "York Minster – full accounts, 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "The Mailing" (PDF). dioceseofyork.org.uk. 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "The Mailing" (PDF). dioceseofyork.org.uk. 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "The Mailing" (PDF). dioceseofyork.org.uk. 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "50th Anniversary of the Astronomical Clock" (PDF). York Minster News. York Minster. December 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ Archive of Mystery Plays at National Centre for Early Music.

- ^ "York Mystery Plays review – an epic medieval disaster movie". The Guardian. 2 June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Sarah (1999). Stained Glass at York Minster. London: Scala in association with the Dean and Chapter of York. ISBN 1-85759-219-0.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Neave, David (1995) [1972]. Yorkshire: York and the East Riding (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071061-2.

- Willey, Ann (1998). York Minster. London: Scala. ISBN 1-85759-188-7.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Information on the history of York Minster and photographs

- Independent travel guide to York Minster with pictures

- York Minster information and pictures Archived 3 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- York Minster Information and Images www.theminsteryork.co.uk[permanent dead link]

- History of York – the Minster theme on the city's history website

- Photo essay on interior of York Minster

- VR York Tour Archived 14 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine Virtual Tour of York Minster – view the interior and exterior of the Minster in York

- York Minster, QuickTime image

- Photos Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- A history of the choristers of York Minster

- The Guardian Christmas illuminations

- The Cathedral Church of York, 1899, by A. Clutton-Brock, from Project Gutenberg

- Photos and plans

- Sound of the chime and photography of York Minster

- Rose—Illuminating York by Ross Ashton & Karen Monid – "son et lumiere" images.

- York Minster

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Anglo-Catholic church buildings in North Yorkshire

- Carillons

- Church of England church buildings in North Yorkshire

- Church of England church buildings in York

- Diocese of York

- English Gothic architecture in North Yorkshire

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- Grade I listed churches in York

- Museums in York

- Musical instrument museums in England

- Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

- Scheduled monuments in York

- Tourist attractions in York

- 13th-century church buildings in England

- Scheduled monuments in North Yorkshire

- Affirming churches in England