Fitzsimons Army Medical Center

| Fitzsimons Army Medical Center | |

|---|---|

Unit Crest | |

| Active | 1918–1996 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Type | Hospital |

| Motto(s) | "Comfort, Heal, Relieve" |

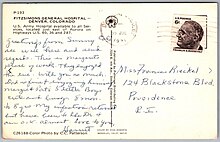

Fitzsimons Army Hospital, also known as Fitzsimons General Hospital, renamed Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in 1974, and Fitzsimons Building[1] in 2018 was a U.S. Army facility located on 577 acres (234 ha) in Aurora, Colorado. The facility opened in 1918 and closed in 1996. The grounds were then redeveloped for civilian use as the Anschutz Medical Campus and the Fitzsimons Innovation Community.

History

[edit]

Native people

[edit]The land the facility occupies is the sacred and ancestral territory of the Pawnee and Jicarilla Apache peoples. These groups controlled the land in the 1500s.[2]

Founding

[edit]The facility was founded by the United States Army during World War I arising from the need to treat the large number of casualties from chemical weapons in Europe. Denver's reputation as a prime location for the treatment of tuberculosis led local citizens to lobby the Army on behalf of Denver as the site for the new hospital. In February 1918, the War Department recommended to Congress $500,00 be expended on constructions of the Denver hospital.[2] Additionally, local business owners raised $150,000 to purchase the property east of Denver that previously belonged to A. H. Gutheil Nursery.[3] U.S. Army General Hospital No. 21, as it was first called, had ground breaking in April 1918, was formally dedicated and opened on October 13, 1918, in Aurora, which at the time had a population of less than 1,000. The campus consisted of 86 stucco buildings and capacity for 1,400 patients. The first commander of the hospital was Colonel William P. Harlow, a Boulder native. He began his term on August 27, 1918, and had been the Dean of the University of Colorado Medical School before World War I.[2] Elizabeth D. Reid served as the first head nurse. Construction of the hospital was not officially completed until 1919. The final construction cost was $3.2 million.[3]

1920s

[edit]On July 1, 1920, the facility was formally renamed the Fitzsimons General Hospital after Lt. William T. Fitzsimons, the first American medical officer (a surgeon) killed in World War I.[4] By the 1920s, the hospital was the largest tuberculosis hospital in the United States using heliotherapy as one of the major forms of treatment. The hospital admitted and discharged approximately 300 patients per month while also serving as a general hospital for active military and veterans in the Denver area.[3] In 1926 the Fitzsimons radio station KEUP was started.[2]

1930s and early 1940s

[edit]

The facility was being prepared for closure by the Army during the economic depression of the 1930s.[2] In April 1933, Surgeon General R. U. Patterson sent a radiogram stating that Fitzsimons would be abandoned and all patients transferred.[2] However, Denver's reputation for treating tuberculosis and the consequences of losing 1,000 jobs at Fitzsimons led to citizen lobbying for Denver to be the site of a new Army hospital. U.S. Senator Lawrence C. Phipps was also a promotor of Fitzsimons Army Hospital and his efforts led to Congress approving funding in November 1934 to keep the hospital open.[2][5] The Army maintained the hospital in the budget for a few years before asking for work-relief funds to rebuild and modernize the facility in 1935. From 1935-1936 several improvement projects were carried out by the Works Progress Administration (WPA).[3] President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Fitzsimons on October 12, 1936, and vowed to maintain the hospital.[2] In 1937, the land needed for construction of a new facility was officially turned over to the federal government, which paved the way for future development. In 1938, Congress approved $3.75 million in Public Works Administration funds for a new hospital and construction of a new main building, known as Building 500, began in January 1939 and was completed in 1941.[6][7] At the time, it was the largest structure in Colorado and the largest single hospital structure ever built by the Army.[4] The building completed with 290,000 sq ft, 1,800 rooms, ten stories, and 2,252 beds. The property was divided into two sections along a line extending through Monteview Street. Property north of the line was designated for commercial development. Property to the south was designated for medical and educational purposes, which is the current day School of Medicine and many hospitals. Building 500 got its name from its location exactly at the center of the south property and 500 yards from Montview Street. The building construction followed a Modernistic style, which was state-of-the-art for military hospitals at the time. The supervising architect for the Army Quartermaster Corps, L. M. Leisenring oversaw the design and construction of the building in a Modernistic Art Deco style.[6] Building materials included several blended colors of face brick, Texas sandstone, Yule Marble for the main entrance, Colorado Travertine stone for the walls, and granite for the paving and curbs under the entrance.[2] The grand portico above the main entrance was inscribed with three Latin phrases: Vita Brevis Ars Vero Longa, meaning "Life is short, art is enduring", Salus Virtus et Robur Artubus Scientia et Virtute et Bonis Artibus, meaning "Health, strength and vigor to the sinews (body) with the help of science, virtue and the arts", and Non Sibi Sed Proximo ,"Not for himself but for the next one to him". At the time the building was dedicated by Congressman Lewis on December 3, 1941, it had 290,000 sq ft and 608 beds.[3]

World War II

[edit]Four days after the dedication, Pearl Harbor was attacked and soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who injured began arriving on December 17.[8] At the peak of its development during World War II, the number of hospital beds increased to 3,500 and the hospital contained as many as 5,000 patients at a time. This was accomplished by the hasty construction of many temporary buildings. The hospital campus had also grown to become the largest military hospital in the world with 322 buildings on about 600 acres. In April 1943, a post newspaper "The Stethoscope" was first published and formal publication lasted until the closure of the base. In 1944, the first members of the Women's Army Corps (WAC) arrived at Fitzsimons.[2] In 1947, the Prisoner of War camp was razed.[2] In 1948, Fitzsimons became one of the first hospitals to use streptomycin to treat tuberculosis.[2]

1950s

[edit]In the 1950s, tuberculosis cases dropped with improvements in public health and lung cancer and other chest diseases became the focus.[3] The hospital was renamed Fitzsimons Army Hospital in July 1950 and a pre-school and kindergarten were opened.[2] In 1952, the 8th floor auditorium was named for Col. George E. Bushnell, who was responsible for inspecting and identifying the site of the future hospital in 1918. In 1953, Korean prisoners of was were treated at Fitzsimons and three departments were established: Medicine, Surgery, and Neuropsychiatry.[2] In 1955, a new chapel and credit union were opened.

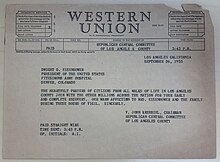

President Eisenhower stay, 1955

[edit]The facility was used heavily during World War II to treat returning casualties and became one of the Army's premier medical training centers. In the 1950s, Dwight Eisenhower received treatment at the facility three separate times for his heart condition while he was president. In the early morning hours of September 24, 1955, about five weeks into a "work and play" vacation at his in-laws' house in Denver, he suffered a myocardial infarction and was placed in an oxygen tent at the facility. He spent seven weeks convalescing in his suite on the eighth floor (Room 8002) of Building 500.[9]

The entirety of the floor was cordoned off from the rest of the hospital, and was referred to as the "Western White House". Flowers lined the hallways of the suite as well wishes sent from people all over the world. Mamie would assist in reading and responding to those that sent messages of good wishes and prayerful concerns to the President. Eisenhower was taken outside to the roof when his health improved and he would occasionally paint scenes of his memories from Colorado. He was motivated to try painting for relaxation after seeing how it had helped Winston Churchill. Mamie Eisenhower was provided with her own bedroom so she could be close by and assist in her husband's recovery. Her room was similar to her husband's with the exceptions of having a sofa, chair, television, and telephone. Mamie asked for her pink toilet seat to be shipped from the White House and installed in her room (Room 8021). The toilet seat is now in Eisenhower's family home in Gettysburg, PA. Another room on the eighth floor was designated for Secret Service use. Only authorized visitors were allowed to site in this room and wait to meet with the President. President Eisenhower's personal physician, Dr. Howard McCrum Snyder, also had a room on the eighth floor in order to be available at all times. Also on the eighth floor, the Bushnell Auditorium uses converted from hosting medical conferences to a command post and office for Presidential Aide Colonel Robert Schultz, and a theater for Mamie and others to watch westerns, comedies, and other movies popular at the time.

Eisenhower celebrated his 65th birthday, October 14, 1955, while in the Fitzsimons hospital. Of the many gifts he received, he frequently used a set of maroon pajamas embroidered with "Much Better Thanks" on the left pocket given to him by the White House Press Corps.[10] Eisenhower worn these pajamas on his first public appearance on October 25, 1955 on the hospital rooftop, an occasion documented on the cover of Life Magazine (vol. 39, 1955). The President and Mrs. Carlos Castillo-Armas of Guatemala visited Eisenhower on November 9, 1955. After his discharge on Armistice Day, November 11, 1955, Eisenhower spent a few weeks with his family in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania at his family's farm.[9] In October 1956, Eisenhower returned to Denver to visit with the people who had nursed him back to health. He talked briefly to the thousands of assembled well-wishers and then proceeded to a huge tent that was set up for his visit with Fitzsimons personnel.[2]

After Eisenhower's stay, the suite stood vacant for many years, eventually becoming an office. In 1995, the Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended the closure of Fitzsimons and the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center secured much of the Fitzsimons site for the relocation of the Denver campus at East 9th Avenue and Colorado Boulevard.[11] In 2000, work began to restore the suite of rooms on the hospital's eighth floor to appear as they did when Eisenhower was recovering there. This was made possible through a $67,100 SHF grant, a $10,000 donation from Wells Fargo, and matching funds from the University of Colorado. The restored suite opened in 2003 and features many time period pieces such as nurse-call buttons, glass ashtrays, a Secret Service sitting room, nurse's station, and a private dining room.[6] Also viewable from the roof deck on the south side was a golden eagle on top of the flag pole, which signifies Building 500 as one of only seven locations in the United States that served as a seat of government.

Clinical Specialist School era, 1960s

[edit]On January 1, 1960, the name was changed back to Fitzsimons General Hospital and became further known for its "Clinical Specialist School," at that time one of the longest professional schools for enlisted US military personnel.[2] US Army medics of varied service and rank studied both academically and in rotation on the hospital's wards. At the end of close to a year of study, those students who had previously gained "Combat Medic" (91A10) and "Medical Specialist" (91B20) proficiency now graduated as "Clinical Specialists" (91C20), a level of medical proficiency which paralleled that of the "Licensed Practical Nurse" (LPN or LVN) in the civilian world, but inclusive of additional skills such as treatment of basic wound trauma and elemental surgical methods more applicable to military wartime nursing. Most of the 91C20s ("Ninety-one Charlies") would find themselves working with registered nurses in military hospital settings, but as the Vietnam War was at its height in the late 1960s, certain graduates would move on to Special Forces assignments and such as Medical Civic Action assistance (MEDCAPs) for those Vietnamese living in more remote regions, and so often forced to go without the benefits enjoyed by Vietnamese living near cities. "Ninety-one Charlies" proved well suited[according to whom?] to a medical niche previously wanting for civilian-certified Practical Nurses.

During this decade, the hospital had many patients that were amputees, approximately 100 per year. [12] This figure represented 10 percent of the orthopedic population at the time.[13]

1970s

[edit]In 1971, a drug dependency program began for returning Vietnam veterans.[2] In 1972, Fitzsimons became the first Army hospital to obtain an Argon Ion Laser Photocoagulator, which was used in treating some eye problems.[2] On March 1, 1973, the hospital took its fourth name, Fitzsimons Army Medical Center, one of eight such institutions in the country.[2][14] In 1977, the tuberculosis ward was closed. In March 1979, a $3.75 million CT scanner was delivered.[2]

1980s

[edit]In 1980, the medical center became the first to have a full-time civilian home nursing services coordinator.[2] In November 1984, a new $1.8 million cardiac catheterization laboratory opened. In 1989, the medical center was removed from Base Closure studies.[2]

Closure and transfer of facilities, 1990s

[edit]

With the end of the Cold War in 1991, Fitzsimons was showing its age and not directly involved with any active military installations.[3] In July 1995, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission recommended the closure of the facility, with the exception of the Edgar J. McWhethy Army Reserve Center, located at the southeast corner of the installation. The hospital took its fifth name as U.S. Army Garrison Fitzsimons with the closure of the larger Army base on June 8, 1996. At the time of closure, Fitzsimons was one of Aurora's largest employers, with approximately 3,000 employees and $328 million in economic activity. The healthcare duties of the hospital were transferred to Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

University of Colorado

[edit]In summer 1996, the University of Colorado commissioned a study of the Fitzsimons site to determine feasibility of moving to the site. On November 14, 1996, the Board of Regents approved te Plan for Acquisition and Development of Fitzsimons Property. An agreement with the City of Aurora Regarding Redevelopment of Fitzsimons Property was approved on April 24, 1997.[15] The closure was completed in 1999 and the reserve center was relocated to the northeast portion of the site. The projected $5 billion (Economic Contributions of Activities at Fitzsimons Life Science District and the UC Denver Anschutz Medical Campus - Sammons/Dutton LLC, 2008) redevelopment of the facility into civilian use currently includes the construction of the University of Colorado Hospital's $147 million Anschutz Inpatient Pavilion, and the $509-million Children's Hospital. The medical campus also includes University of Colorado Denver medical education and research facilities, including the Ben Nighthorse Campbell Center for Native American Research, named in honor of the U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado. In 2008, the redeveloped Fitzsimons campus employed 16,000 workers and generated approximately $3.5 billion for Colorado's economy.[3]

| Name | Years |

|---|---|

| U.S. Army General Hospital No. 21 | 1918-1920 |

| Fitzsimons General Hospital | 1920-1950 |

| Fitzsimons Army Hospital | 1950-1960 |

| Fitzsimons General Hospital | 1960-1973 |

| Fitzsimons Army Medical Center | 1973-1996 |

| U.S. Army Garrison Fitzsimons | 1996 |

Postal history

[edit]

The hospital generated and received large volumes of postal material when letter writing was more common, and still houses a U.S.P.S postal annex providing services to the Anschutz campus community to this day.

Efforts have been made to preserve the postal boxes in the ground floor lobby as well as the elaborate mail chute system that was used to collect mail from all eight floors of the building.

Building restoration and rehabilitation

[edit]Two SHF grants have been awarded to support restoration and rehabilitation efforts on Building 500. Grant number 16-02-014 was awarded in 2016 to the Anschutz Medical Campus from the Acquisition and Development Fund in the amount of $200,000. Grant number 19-01-006 was awarded in 2019 to the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado, a body corporate, for and on behalf of the University of Colorado Denver from the Acquisition and Development Fund in the amount of $200,000. Both of these grants were used to restore windows on the building.[16]

Additional facilities currently built at the former base include the Bioscience Park Center and Bioscience East (multi-tenant commercial lab buildings in the planned 6,100,000-square-foot (570,000 m2) Colorado Science+Technology Park at Fitzsimons) and 21 Fitzsimons(a residential/retail town center). The Veterans Affairs Medical Center was opened in 2018.

In the Spring of 2013 a Donor Memorial Garden opened on the southeast lawn of the building. The garden serves to honor the whole body donors that are part of the Colorado State Anatomical Board and a popular meeting place on campus. Each class that was involved in fundraising for the garden are represented with a paver engraved with a quote voted on by class members.[17]

United States Army Medical Equipment and Optical School

[edit]In 1963, the United States Army Medical Equipment and Optical School (USAMEOS) was transferred to the installation.[2] USAMEOS provided technicians trained in biomedical equipment repair or optical laboratory operations. Biomedical equipment repair personnel (referred to as BMETs—pronounced 'bee/mets') were assigned to military medical units to install, maintain, repair, and calibrate sophisticated life support, diagnostic, imaging, and general medical equipment. Military Occupation Specialties (MOS) graduating from USAMEOS included: 35G, 35S, 35T, and 35U. Optical laboratory technicians were designated as 42E upon graduation of the 21-week optical training course. In the hallways of the USAMEOS training facility hung the pictures of graduating BMET classes over decades of operation.

When the USAMEOS program was first developed, the training program was divided into Basic and Advanced Courses. The basic course work was 20 weeks long. The advanced course work was 32 weeks long. The courses were later changed to a 40-week basic class (35G) and 32-week advanced course (35U). The graduates of the basic course were known as "Super G's" referring to the MOS of 35G. With a small amount of additional course work, USAMEOS graduates could earn an AAS in Biomedical Equipment Maintenance from Regis University in Denver. During the 1990s, the MOS designation was changed to 91A for Biomedical Equipment Repair Technician, and the Basic Course consisted of a 38-week course broken up into twelve modules. Didactic Modules included Anatomy and Physiology, Basic Soldering, AC/DC theory and Ohm's law, electron theory, Transistor Theory, Digital Circuits, Basic Troubleshooting, Dental and Pneumatic Devices, heating and cooling, Sterilizers and Ultrasonic Cleaners, Linear Circuits, Spectrophotometers and Solid State Relays, advanced troubleshooting, cryogenics primer, high and low capacity modules of X-ray, The school culminated in a field problem where students lived in ISOs and temper tents while filling out paperwork in the field environment to include pulling guard duty and setup of mobile sterile operating units and generators.. After graduation from the basic course, students would typically be assigned to an operational unit for practical work between the Basic and Advanced Courses. Technical training at USAMEOS was accelerated, 8 hours per day in class, it was intensive and provided both engineering theory and hands on learning opportunities in an extensive set of labs. The school closed in 1999 due to base closure.

Fitzsimons was a training center for phase II of the ARMY practical nurse (91C) from —- to the last class graduating 22 March 1996.

Notable people

[edit]- Earl W. Mann came to General Hospital No. 21 after he was injured by mustard gas in France in 1918, elected to Colorado State Legislature in 1938 and served six nonconsecutive terms.

- Queen Marie of Romania visited the hospital in November 1926.[2]

- Floyd Gibbons World War I correspondent visited Fitzsimons in August 1932.[2]

- James E. Bowman was Chief of Pathology here during the 1950s.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower was hospitalized here for several weeks in 1955 due to a heart attack.

- John Kerry was born here on December 11, 1943, while his father was receiving treatment for tuberculosis.[18]

- Lord Bernard Montgomery British Field Marshal visited President Eisenhower in 1955.[2]

- Donato LaRossa served as Assistant Chief of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery here in the mid-1970s.

- Princess Anne of Britain visited in June 1982.[2]

- Notable visitors to the building include: President Warren G. Harding, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Bob Hope, Ed Sullivan, Bobbie Gentry, Gladys Knight, Bob Dole, and Richard Nixon.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Elliman, Donald (September 14, 2018). "Building 500 Renamed the Fitzsimons Building - 9/14/2018". CU Anschutz. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Littlejohn, Helen, ed. (1996). Annual Review: A History and Report of Fitzsimons Army Medical Center. Aurora, Colorado, United States: Public Affairs Office, Fitzsimons Army Medical Center.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Fitzsimons General Hospital | Colorado Encyclopedia". coloradoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ a b Colfax: Main Street Colorado. 2007. Havey Productions.

- ^ "Belcaro / Phipps House". History Colorado. September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Fitzsimons General Hospital, Main Hospital Building". History Colorado. September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Fitzsimons General Hospital | Denver Public Library Special Collections and Archives". history.denverlibrary.org. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ "Preserving Colorado (part 2)". History Colorado. September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Barr, Justin; Pappas, Theodore N. (March 2022). "Stricken Before Election: Presidential Health Crises From 1880 to 2020". Annals of Surgery Open. 3 (1): e126. doi:10.1097/AS9.0000000000000126. ISSN 2691-3593. PMC 10431273. PMID 37600098.

- ^ White, Cody (September 22, 2016). ""Heart Attack Strikes Ike," President Eisenhower's 1955 Medical Emergency in Colorado – The Text Message". National Archives. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center Commemoration Medallion". History Colorado. September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Steinbach, T. (August 1977). "Total rehabilitation for amputees in special conditions". Prosthetics & Orthotics International. 1 (2): 125–126. doi:10.3109/03093647709164621. ISSN 0309-3646. PMID 615296.

- ^ Kuehn, John T. (April 2012). "A Review of "Engineers at War (U.S. Army in Vietnam Series)"". History: Reviews of New Books. 40 (2): 62. doi:10.1080/03612759.2012.644512. ISSN 0361-2759.

- ^ "The Women of the WAC". History Colorado. September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Claman, Henry; Shikes, Robert (2000). The University of Colorado School of Medicine: A Millennial History. Aurora, CO. pp. 5–6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Fitzsimons General Hospital Main Building No. 500". History Colorado. September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Twichell, Tonia (May 1, 2013). "Donor Memorial Garden". Donor Memorial Garden. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ White, Cody (September 22, 2016). ""Heart Attack Strikes Ike," President Eisenhower's 1955 Medical Emergency in Colorado – The Text Message". National Archives. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Eisenhower Suite: University of Colorado School of Medicine

- Defense Environmental Restoration Program: Fitzsimons Army Medical Center

- "Health-Care Owners Seek Cure For Projects". DesignBuild Magazine. Archived from the original on 2003-02-07.

- "Department of Veterans Affairs" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2004-02-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (86.8 KB) U.S. House of Representatives hearings on conversion of the site

- Buildings and structures in Aurora, Colorado

- Military hospitals in the United States

- Military in Aurora, Colorado

- Military installations in Colorado

- Defunct hospitals in Colorado

- Former medical facilities of the United States Army

- Hospital buildings completed in 1918

- Hospital buildings completed in 1941

- Hospitals established in 1918

- Skyscrapers in Colorado

- 1918 establishments in Colorado

- 1999 disestablishments in Colorado