Duchy of Brunswick

Duchy of Brunswick Herzogtum Braunschweig (German) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–1918 | |||||||||

The Duchy of Brunswick within the German Empire | |||||||||

Duchy of Brunswick (orange) in 1914 | |||||||||

| Status | State of the German Confederation, the North German Confederation, and the German Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Braunschweig | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | Evangelical Lutheran State Church in Brunswick | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||

• 1813–1815 | Frederick William (first) | ||||||||

• 1913–1918 | Ernest Augustus (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Landesversammlung | ||||||||

| Historical era | Modern era | ||||||||

| 1815 | |||||||||

| 8 November 1918 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1910[1] | 3,672 km2 (1,418 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1910[1] | 494,339 | ||||||||

| Currency | Thaler 1842–1856 vereinsthaler 1858–1871 Goldmark 1873–1914 Papiermark 1914–1918 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||

The Duchy of Brunswick (German: Herzogtum Braunschweig) was a historical German state that ceased to exist in 1918. Its capital was the city of Brunswick (Braunschweig). It was established as the successor state of the Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. In the course of the 19th-century history of Germany, the duchy was part of the German Confederation, the North German Confederation and from 1871 the German Empire. It was disestablished after the end of World War I, its territory incorporated into the Weimar Republic as the Free State of Brunswick.

History

[edit]Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

[edit]

The title "Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg" (German: Herzog zu Braunschweig und Lüneburg) was held, from 1235 on, by various members of the Welf (Guelph) family who ruled several small territories in northwest Germany. These holdings did not have all of the formal characteristics of a modern unitary state, being neither compact nor indivisible. When several sons of a duke competed for power, the lands often became divided between them; when a branch of the family lost power or became extinct, the lands were reallocated among surviving members of the family; different dukes might also exchange territories. The unifying element of all these territories was that they were ruled by male-line descendants of Duke Otto I (ruled 1235–1252).

After several early divisions, Brunswick-Lüneburg re-unified under Duke Magnus II (d. 1373). Following his death, his three sons jointly ruled the duchy. After the murder of their brother Frederick I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, brothers Bernard and Henry redivided the land, Henry receiving the territory of Wolfenbüttel.

From 1432 forward the Principality of Wolfenbuettel became the capital of the Duchy of Brunswick and Luneburg. It is widely understood and confirmed that from the year 1546 forward there became two dynastic lines of the house of Este-Guelph Brunswick: "the senior", from Brunswick-Wolfenbuettel, and one called "the younger branch" from Calenburg-Hanover. The ruling monarchs of Brunswick and Lunenburg continued to govern the greater Duchy from the Wolfenbuettel principality till 1754, when temporarily the Brunswick principality was used as a capital to mitigate[clarification needed] while the Brunswick[clarification needed] wished to become an Imperial free city.

Duchy of Brunswick

[edit]

Formal sovereignty confirmed

[edit]The territory of Wolfenbüttel was recognized as a sovereign state by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. It had been a portion of the medieval Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg. The northern principality known as Lüneburg remained fragmented and largely under control of Wolfenbuettel. However, in 1702, the Prince of Calenberg and Celle averted the extinction of the line through a marriage with the low-born Eleonore d'Esmier d'Olbreuse, who from 1705 passed to her successors a united Lüneburg to said princes, later i.e. the Elector of Hanover.[clarification needed] The princes of Wolfenbüttel maintained their supremacy over the subject vassal state of Lüneburg, but recognized its semi-sovereignty.

The Wolfenbüttel principality had from 1807 to 1813 been held as part of the Kingdom of Westphalia. The Congress turned it into an independent country as the Duchy of Brunswick. These acts were protested by the de facto and de jure Duke Charles II in annual protests until his death. His grandson Ulric de Civry (brother of Frédéric de Civry) continued in full ducal regalia and claim maintaining these protests (against Prussia, Hanover, and even some parts of the Council of Vienna) until his assassination in 1935 at Geneva Switzerland.

Charles II (1815–1830)

[edit]The underage Duke Charles, the eldest son of Duke Frederick William (who had been killed in action), was put under the guardianship of George IV, the Prince Regent of the United Kingdom and Hanover.

First, the young duke had a dispute over the date of his majority. Then, in 1827, Charles declared some of the laws made during his minority invalid, which caused conflicts. After the German Confederation intervened, Charles was forced to accept those laws. His administration was considered corrupt and misguided.[2]

In the aftermath of the July Revolution in 1830, Charles had to leave the country. His absolutist governing style had alienated the nobility and bourgeoisie, while the lower classes were disaffected by the bad economic situation. During the night of 7–8 September 1830, the ducal palace in Braunschweig was stormed by an angry mob, set on fire and destroyed completely. Charles fled the country, but without abdicating.[3]

William VIII (1830–1884)

[edit]When Charles' brother William VIII arrived in Brunswick on 10 September, he was received joyfully by the people. William originally considered himself only his brother's regent, but after a year declared himself ruling duke. Charles made several desperate attempts, unsuccessfully, to depose him.

William left most government business to his ministers, and spent most of his time outside of his state at his possessions in Oels. After the revolution of 1830, liberal reforms were made and a new constitution was adopted on 12 October 1832. While the number of voters was limited by a system of census suffrage to about 40% of Brunswick's male population, the parliament of Brunswick was granted more rights than in most other German states at the time and the duke's budget and powers were significantly limited.[4]

While William joined the Prussian-led North German Confederation in 1866, his relationship to Prussia was strained, since Prussia refused to recognize Ernest Augustus, Crown Prince of Hanover, his nearest male-line relative, as his heir.

While the Kingdom of Hanover was annexed by Prussia in 1866, the Duchy of Brunswick remained sovereign and independent. It joined first the North German Confederation and in 1871 the German Empire.

In the 1870s, it became obvious that the then-senior branch of the ruling House of Welf would die with Duke William. By house law, a member of the House of Hanover would have ascended the ducal throne. However, the Hanoverians still refused to accept the Prussian annexation of their kingdom. As a result, Prussia was unwilling to let George V of Hanover or his son, Ernest Augustus, succeed to Brunswick. Berlin would only agree to the Hanoverians becoming dukes of Brunswick under severe conditions, including swearing allegiance to the German constitution and renouncing all claim to Hanover.

By a law of 1879, the Duchy of Brunswick established a temporary council of regency to take over at the duke's death. If Ernest Augustus–who had been created the Duke of Cumberland in the British peerage–were unable to succeed, the council would also be empowered to appoint a regent. With William's death in 1884, the Wolfenbüttel line came to an end. The Duke of Cumberland then proclaimed himself Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick. However, since he still claimed to be the rightful King of Hanover, the Federal Council ruled that he would violate the peace of the German Empire if he succeeded to Brunswick. Lengthy negotiations ensued, but were never resolved.

Regency (1884–1913)

[edit]Two regents were appointed: first, Prince Albert of Prussia until his death in 1906, and then Duke John Albert of Mecklenburg.[5]

Ernest Augustus (1913–1918)

[edit]

The need for a regent ended in 1913. The Duke of Cumberland's eldest son having died in 1912, the elderly duke renounced Brunswick in favor of his youngest son, Ernest Augustus, who married Emperor Wilhelm II's daughter, swore allegiance to the German Empire and renounced all claims to Hanover. Accordingly, he was allowed to ascend the throne of the duchy in November 1913.

In the midst of the German revolutions of 1918, the duke had to abdicate, and the Free State of Brunswick was founded as a member state of the Weimar Republic.

Dukes and Regents of Brunswick

[edit]House of Brunswick-Dannenberg

[edit]- 1815–1830: Charles II, son of Frederick William. Forced to flee Brunswick in 1830 and succeeded by his brother.

- 1830–1884: William VIII. Brother of Charles II. Last of the Brunswick line, following which the legal succession passed to the Hanoverian royal family, which had been dispossessed by Prussia following the Austro-Prussian War of 1866.

Regency

[edit]- 1885–1906: Albert, Prince of Prussia, regent. The German government prevented the succession of the Hanoverian Duke of Cumberland to the throne of Brunswick and substituted a Prussian regent for the duke.

- 1907–1913: Duke John Albert of Mecklenburg, regent

House of Hanover

[edit]- 1913–1918: Ernest Augustus

-

Charles II

-

Prince Albert of Prussia

-

John Albert of Mecklenburg

-

Brunonia, the national personification of Brunswick

Geography

[edit]

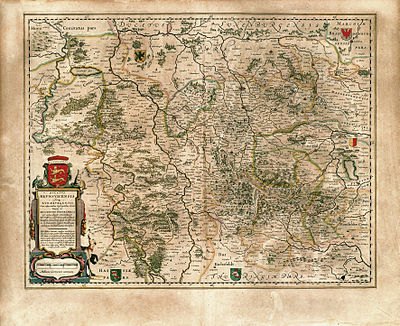

The Duchy of Brunswick consisted of several non-connected parts - three larger and seven smaller ones. The biggest and most populous of those was the area surrounding the cities of Braunschweig, Wolfenbüttel and Helmstedt as well as the Elm, which extended from the river Aller in the north to the Harz mountains in the south. The western part with the town of Holzminden extended from the river Weser in the east to the Harz Foreland in the west. The southern part with the town of Blankenburg was located in the Harz mountains. The Duchy's smaller exclaves were Thedinghausen near Bremen, Harzburg, Calvörde, Bodenburg and Östrum, Ostharingen near Goslar, Ölsburg near Peine and a small woodland near the Fallstein. The Duchy of Brunswick was almost entirely surrounded by the Prussian Provinces of Hanover and Saxony, in the south-east it also bordered the Duchy of Anhalt and in the west the Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont and the Prussian Province of Westphalia.

The western part of the Duchy lay in the Weser Uplands, the central and southern parts in the northern Harz Foreland and the Harz mountains. The northern part was located on the border between the North German Plain and the Central Uplands of Germany. The Duchy's highest peak was the Wurmberg at 971 metres (3,186 ft). The major rivers that ran through Brunswick were the Weser, Aller, Leine, Oker, Bode and Innerste.

Main parts and exclaves of Brunswick by size

[edit]| Region or exclave[6] | Area in square kilometers |

Shared borders with |

|---|---|---|

| Main part with Braunschweig, Wolfenbüttel, Helmstedt | 1808 | Province of Hanover, Province of Saxony |

| Western part with Holzminden, Seesen, Gandersheim | 1107 | Province of Hanover, Province of Westphalia, Waldeck |

| Lower Harz with Blankenburg, Braunlage | 475 | Province of Hanover, Province of Saxony, Anhalt |

| Harzburg | 125 | Province of Hanover |

| Calvörde | 102 | Province of Saxony |

| Thedinghausen | 56 | Province of Hanover |

| Bodenburg and Östrum | 10 | Province of Hanover |

| Ostharingen | 4 | Province of Hanover |

| Ölsburg | 3 | Province of Hanover |

Districts

[edit]

The Duchy of Brunswick was subdivided into six districts (Kreise) in 1833. The districts were further subdivided into cities or towns (Städte) and more rural townships (Ämter).

| District | Area in square kilometers (1 Dec 1910)[1] |

Population (1 Dec 1910)[1] |

Cities and Ämter[7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| District of Blankenburg | 474,67 | 35,989 | Blankenburg, Hasselfelde and Walkenried |

| District of Braunschweig | 543,87 | 191,112 | Braunschweig, Riddagshausen, Thedinghausen (since 1850) and Vechelde |

| District of Gandersheim | 533,92 | 50,435 | Gandersheim, Seesen, Lutter am Barenberge and Greene |

| District of Helmstedt | 799,56 | 78,514 | Helmstedt, Schöningen, Königslutter, Vorsfelde and Calvörde |

| District of Holzminden | 584,11 | 51,756 | Holzminden, Stadtoldendorf, Eschershausen, Ottenstein and Thedinghausen (until 1850) |

| District of Wolfenbüttel | 735,92 | 86,533 | Wolfenbüttel, Salder, Schöppenstedt and Harzburg |

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1831 | 245,798 | — |

| 1836 | 258,309 | +5.1% |

| 1843 | 267,563 | +3.6% |

| 1849 | 270,085 | +0.9% |

| 1855 | 269,213 | −0.3% |

| 1858 | 273,394 | +1.6% |

| 1861 | 281,708 | +3.0% |

| 1864 | 292,708 | +3.9% |

| 1867 | 302,801 | +3.4% |

| 1871 | 311,764 | +3.0% |

| 1875 | 327,493 | +5.0% |

| 1885 | 372,452 | +13.7% |

| 1890 | 403,773 | +8.4% |

| 1900 | 464,333 | +15.0% |

| 1905 | 485,958 | +4.7% |

| 1910 | 494,339 | +1.7% |

In 1910, the Duchy of Brunswick had a population of 494,339 people.

According to the 1885 census, 84.90% (316,208 people) of the Duchy's inhabitants held citizenship of Brunswick, while 54,738 people (14.70%) were citizens of other German states. 1506 people (0.40%) were foreign nationals, among those 785 came from Austria-Hungary, 133 from the United Kingdom, 112 from the United States, 91 from Italy, 83 from the Russian Empire, and 81 from Switzerland.[8]

Religion

[edit]In 1905, 450,760 people or 92.5% of the population adhered to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Brunswick. 26,504 (5.5%) people were Catholic, 4720 (0.97%) adhered to Reformed churches. 1815 (0.39%) people were of Jewish faith.[9]

Largest municipalities by population

[edit]| City or town | Population (1 Dec 1910)[1] |

|---|---|

| Braunschweig | 143,552 |

| Wolfenbüttel | 18,934 |

| Helmstedt | 16,421 |

| Blankenburg am Harz | 11,487 |

| Holzminden | 10,249 |

| Schöningen | 9,773 |

| Seesen | 5,381 |

| Harzburg | 4,728 |

| Oker | 3,984 |

| Stadtoldendorf | 3,728 |

| Langelsheim | 3,611 |

| Schöppenstedt | 3,226 |

| Königslutter | 3,126 |

| Bündheim | 2,982 |

| Braunlage | 2,811 |

| Gandersheim | 2,711 |

| Hasselfelde | 2,649 |

Economy

[edit]In 1905, out of 1,000 residents 455 were working in the industrial sector, mining or construction, 289 were working in agriculture and forestry, 121 in commerce, 57.3 were employed in the civil service and 70 were working in miscellaneous other professions.[9]

Transport

[edit]The Duchy of Brunswick State Railway was the first state railway in Germany. The first section of its Brunswick–Bad Harzburg railway line connecting Braunschweig and Wolfenbüttel opened on 1 December 1838, as the first railway line in Northern Germany.[10] In the 1870s, the Duchy of Brunswick State Railway merged with the Royal Prussian State Railways. Some other railways of secondary importance were operated by the Brunswick State Railway Company, founded in 1884.

Sports

[edit]In 1847, MTV Braunschweig was founded as the first sports club in Brunswick.[11]

Brunswick also played a pioneering role in the history of association football in Germany: Konrad Koch, a school teacher from Braunschweig, was the first to write down a German version of the rules of football, and, together with August Hermann, also arguably organized the first football match in Germany between pupils from his school Martino-Katharineum in 1874.[12][13]

The Duchy of Brunswick Football Association (German: Fußballbund für das Herzogtum Braunschweig) was founded in May 1904.[14] Eintracht Braunschweig, founded in 1895, quickly became one of the leading football clubs in Northern Germany. To this day, the team plays in the colours blue and yellow, derived from the flag of Brunswick.

Coat of arms

[edit]

The Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg was formed out of the possessions of senior branch of the House of Brunswick. The House of Brunswick originated from the Italian House of Este. This family acquired the inheritance of the Guelph family by marriage — around the year 1000 — of Azzo II with Kunigunde of Altdorf, daughter of Welf II. Again important possessions were gained in (Lower) Saxony by the marriage of Henry the Black to Wulfhilde of Saxony (d 1126), daughter of the last member of the House of Billung, who had been Dukes of Saxony for five generations. They were made Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg in 1235. In 1269 the house of Brunswick-Lüneburg divided into the branches of Lüneburg and Brunswick (later Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the later Duchy of Brunswick). In 1432 the Principality of Calenberg, the later Electorate of Hanover, split from Brunswick(-Wolfenbüttel), and in 1705 acquired the territory of Lüneburg.

Both branches used in their arms the two lions of Brunswick, the blue lion of Lüneburg and the white steed of Saxony. The use of the lion as a heraldic animal in the House of Guelph goes back to Henry the Lion in the 12th century at least. However, Henry used only a single lion as his symbol. Later accounts by medieval writers that the two golden lions of Brunswick were granted to Henry by the English king, his father-in-law, are deemed fictional by modern historians.[15] It was Henry's sons from his marriage with Matilda of England, the future Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV and Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine, who adapted the Royal Arms of England to display their royal lineage. While Otto's coat of arms showed the three golden lions of England, Henry used only two. The two lions of Henry V then went on to become the symbol of the House of Guelph.[16] The blue lion of Lüneburg was adopted by John I of Lüneburg, who based his coat of arms on the coat of arms of Denmark to emphasise his kinship with the Danish kings.[17] The dukes of Brunswick later added the blue lion to their arms as well, to show their own claim to the territory of Lüneburg.

The white steed was said to be the emblem of the eighth century Saxon duke Widukind, who according to legend rode a black horse before his baptism and a white horse afterwards. In truth, the use of the horse as a symbol for Saxony only goes back to the 14th century, when the House of Guelph, after the ducal title of Saxony had fallen to the House of Ascania, adopted the fictional "ancient" symbol to represent themselves as the true descendants of the old Saxon dukes.[18] Due to the legend associated with it, the white horse became a very popular symbol among the population of Brunswick, even more so than the lions.[19]

Over time, the arms of smaller territories that had been acquired by the Dukes of Brunswick were added to the coat of arms. The coat of arms of the Duchy of Brunswick eventually consisted of a crown and shield, supported by two wild men, on which the blue lion of Lüneburg, the two golden lions of Brunswick, the Saxon steed and the arms of various counties were displayed. The lesser coat of arms of the Duchy of Brunswick showed a crowned shield with the white horse on a red background. The Saxon steed was dropped from the coat of arms during the reign of William VIII.[20] The greater coat of arms of the Duchy of Brunswick, as adopted in 1834, shows a shield with a ducal crown on top and surrounded by the insignia of the Order of Henry the Lion. Displayed on the shield are, from left to right, the blue lion of Lüneburg, the two lions of Brunswick, and the arms of the Counts of Eberstein, Homburg, Diepholz (upper half), Lauterberg, Hoya and Bruchhausen, Diepholz (lower half), Honstein, Regenstein, Klettenberg and Blankenburg.[21] The new lesser coat of arms introduced under William VIII was a return to the arms of Brunswick-Lüneburg, displayed on a crowned shield supported by two lions. The Latin inscriptions read IMMOTA FIDES ("unswerving faithfulness") and NEC ASPERA TERRENT ("they are not afraid of difficulties").

The flag of the Duchy of Brunswick was blue over yellow,[21] and is remarkably similar to the flag of Ukraine. The standard of the dukes of Brunswick given by Siebmachers Wappenbuch, Nuremberg 1878, shows the white horse on a red cloth - this, however, is today assumed to have been in error.[22] The state flag introduced in 1912 was blue over yellow, with a crowned shield with the white horse on a red background in the center.[22]

-

Coat of arms of the Duchy of Brunswick before 1834

-

Lesser coat of arms of the Duchy of Brunswick

-

Saxon steed on an 1860s stamp of Brunswick

-

Coat of arms of Brunswick on an 1866 Vereinsthaler

-

Coat of arms of Brunswick-Lüneburg

-

Coat of arms of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

-

Coat of arms of the Dukes of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Richard Andree: Braunschweiger Volkskunde. 2nd edition. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1901.

- F. Fuhse (ed.): Vaterländische Geschichten und Denkwürdigkeiten der Lande Braunschweig und Hannover, Band 1: Braunschweig. 3rd edition. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 1925.

- Hermann Guthe: Die Lande Braunschweig und Hannover. Mit Rücksicht auf die Nachbargebiete geographisch dargestellt. Klindworth's Verlag, Hannover 1867.

- Otto Hohnstein: Geschichte des Herzogtums Braunschweig. F. Bartels, Braunschweig 1908.

- Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (eds.): Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region. 2nd edition. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2001, ISBN 3-930292-28-9.

- Jörg Leuschner, Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Claudia Märtl (eds.): Die Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte des Braunschweigischen Landes vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. 3 vols. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13599-1.

- Richard Moderhack (ed.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte im Überblick. 3rd edition, Braunschweigischer Geschichtsverein, Braunschweig 1979.

- E. Oppermann: Landeskunde des Herzogtums Braunschweig. Geschichte und Geographie. E. Appelhans, Braunschweig 1911.

- Werner Pöls, Klaus Erich Pollmann (eds.): Moderne Braunschweigische Geschichte. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 1982, ISBN 3-487-07316-1.

- Henning Steinführer, Gerd Biegel (eds.): 1913 – Braunschweig zwischen Monarchie und Moderne. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2015, ISBN 978-3-944939-12-4.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Gemeindeverzeichnis Deutschland 1900 - Herzogtum Braunschweig (in German)

- ^ O. Hohnstein: Geschichte des Herzogtums Braunschweig, Braunschweig 1908, pp. 465–474

- ^ Gerhard Schildt: Von der Restauration zur Reichsgründungszeit, in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, pp. 753–766

- ^ Schildt: Von der Restauration zur Reichsgründungszeit, pp. 772–777

- ^ "Cable News". Fielding Star. 1 June 1907. p. 2.

- ^ Wolfgang Meibeyer: Die Landesnatur. Territorium - Lage - Grenzen, in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, p. 23

- ^ Beiträge zur Statistik des Herzogthums Braunschweig VIII, Braunschweig 1888, pp. 74–75

- ^ Beiträge zur Statistik des Herzogthums Braunschweig VIII, Braunschweig 1888, p. 67

- ^ a b E. Oppermann: Landeskunde des Herzogtums Braunschweig. Geschichte und Geographie, Braunschweig 1911, p. 63

- ^ E. Oppermann: Landeskunde des Herzogtums Braunschweig. Geschichte und Geographie, Braunschweig 1911, p. 64

- ^ Kurt Hoffmeister: Zeitreise durch die Braunschweiger Sportgeschichte: 180 Jahre Turnen und Sport in Braunschweig, Braunschweig 2010, p. 9

- ^ "Die Wiege des Fußballs stand in Braunschweig" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Der Mann, der die "englische Krankheit" einschleppte" (in German). einestages.spiegel.de. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Stefan Peters: Eintracht Braunschweig. Die Chronik, Kassel 1998, p. 22

- ^ Peter Veddeler: Landessymbole, in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, pp. 80–81

- ^ Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 81

- ^ Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 82

- ^ Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 84

- ^ Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 85

- ^ Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 88–89

- ^ a b Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Herzogtums Braunschweig für 1908, Braunschweig 1908, pp. 62–63

- ^ a b Veddeler: Landessymbole, p. 93

External links

[edit]

- Duchy of Brunswick

- States and territories disestablished in 1918

- States and territories established in 1815

- States of the German Empire

- States of the North German Confederation

- States of the German Confederation

- Wolfenbüttel

- 1815 establishments in Europe

- 1918 disestablishments in Germany

- Former duchies

- Former monarchies of Europe