Broad Street (Manhattan)

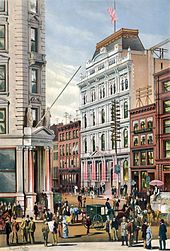

The New York Stock Exchange Building (right) at Broad and Wall Streets | |

| Native name | Heere Gracht (Dutch) |

|---|---|

| Part of | Financial District of Lower Manhattan |

| Coordinates | 40°42′18″N 74°00′42″W / 40.7050°N 74.0116°W |

| Construction | |

| Completion | 1676 |

Broad Street is a north–south street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Originally the Broad Canal in New Amsterdam, it stretches from today's South Street to Wall Street.

The canal drew its water from the East River,[1] and was infilled in 1676 after numerous fruit and vegetable vendors made it difficult for boats to enter the canal.[2] Early establishments on Broad Street in the 1600s included the Fraunces Tavern[3] and the Royal Exchange.[4] Later on the area became the center of financial activity, and all smaller buildings in turn were replaced with grand banks and stock exchange buildings. Most of the structures that stand today date from the turn of the 20th century, along with more modern buildings constructed after the 1950s.

History

[edit]1600s: New Amsterdam canal

[edit]

Broad Street, formerly called Heere Gracht (canal of the lords in Dutch) in old New Amsterdam. Originally an inlet from the East River, the canal was flanked by two solid ranks of three-story houses, with paths in front.[1] Built during the administration of Peter Stuyvesant, the Broad Canal was the original Manhattan landing of the first ferry between Manhattan and Brooklyn, later the Fulton Ferry.[5]

The Lovelace Tavern, in business from 1670 to 1706 and owned by the then-New York colonial governor Colonel Francis Lovelace, occupied part of the current site of 85 Broad Street; however, the bar itself only had frontage on Pearl Street.[6][7][8][9] New York Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt built his home in 1671 on Broad Street, on the future site of Fraunces Tavern.[3] Built as a one-story building in 1675,[citation needed] the Royal Exchange (later known as the Old Royal Exchange and the Merchants Exchange) was a covered marketplace located near the foot of Broad Street close to its intersection with Water Street.[4] 30 Broad Street was once owned by the Dutch church which had erected the city’s second almshouse on the site before 1659. Broad Street was originally a canal first known as "Common Ditch" then later "The Prince’s Ditch".[citation needed]

The canal was filled in 1676 because fruit and vegetable vendors, including Native Americans who came by canoe from Long Island, left the area littered, and fewer and fewer water craft were small enough to use the canal.[2] The paths in front of the rows of houses by the canal were paved in 1676 as well.[1] The road was first paved in 1693.[citation needed] The street saw a lot of change as the centuries progressed from Dutch to British rule and finally independent America. Among the tenants of Broad Street in the 18th century was bookseller Garrat Noel.[10]

1700s: Taverns and halls

[edit]The city's first firehouse for the New York City Fire Department was built in 1736 in front of NYSE on Broad Street. Two years later, on December 16, 1737, the colony's General Assembly created the Volunteer Fire Department of the City of New York.[11]

The Broad Street building for the Fraunces Tavern was bought in 1762 by Samuel Fraunces, who converted the home into the popular tavern first named the Queen's Head. Before the American Revolution, the building was one of the meeting places of the secret society, the Sons of Liberty. In 1768, the New York Chamber of Commerce was founded by a meeting in the building.[12]

After a rebuilt in 1752 that added a meeting hall on the upper story, the Royal Exchange building was the location of the Chamber of Commerce in the City of New York (later Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York) from 1770 until the Revolutionary War. The United States District Court for the District of New York was one of the original 13 courts established by the Judiciary Act of 1789, and it first sat at the Royal Exchange (Merchants Exchange) building on Broad Street.[13][14][15]

1800s: Birth of the financial district

[edit]

The 1835 Great Fire of New York destroyed whatever historical buildings were left from the early times of New Amsterdam/New York.[citation needed] Much of the street was destroyed again in the Great New York City Fire of 1845. In the first two hours of the fire's spread, it reached a large multi-story warehouse occupied by Crocker & Warren on Broad Street, where a large quantity of combustible saltpeter was stored.[16][17] In July 1863,[18][19] the New York Draft Riot in Manhattan became the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War.[20] Upon the outbreak of this riot, Jacob B. Warlow and his police unit contended with a mob on Broad Street,[19] with Warlow also helping quell other riots throughout the city from his station house on Broad Street.[21] As the area became the center of financial activity, all smaller buildings in turn were replaced with grand banks. Most of the structures that stand today date from the turn of the 20th century.[citation needed]

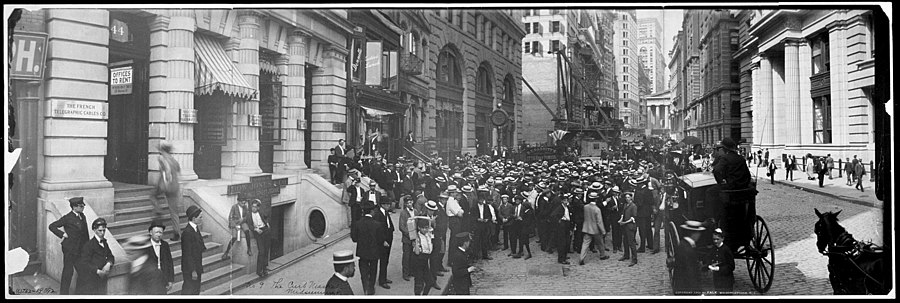

A curb market of curbstone brokers became established on Broad Street in the mid-1800s,[22] growing in part out of the Open Board of Brokers, previously in a building on New Street[23] established in 1864.[24] The Open Board was located at 16 and 18 Broad Street[25] until 1869.[24] After the Open Board joined the Consolidated Exchange, Open Board members specializing in unlisted stocks were left without "a roof over their heads and took to meeting casually in the course of the day in convenient lobbies in the [financial] district".[23] In August 1865, a reporter described the curb market in front of the new exchange building on Broad Street. "There were at least a thousand people on the sidewalk and street... Buyer and seller, speculator and investor, operator and spectator, agent and principal, met face to face, upon the curb and beneath the sweltering sun, opened their mouths wide and screamed all manner of seeming nonsense at each other, while their hats tipped far toward the small of their backs, their eyes strained fiercely and their arms waved wildly above their heads, from which rolled rivers of profuse perspiration."[26] In 1877, a new organization the New-York Open Board of Stock Brokers commissioned the same building at 16 and 18 Broad Street used by the old Open Board.[25]

The Mills Building was completed in 1882[27] as a 10-story structure that stood at 15 Broad Street and Exchange Place,[27] with an L to 35 Wall Street. It adjoined the building that was the home of Equitable Trust Company. It also adjoined the J. P. Morgan & Company Building on both Broad and Wall streets.[28] The curb brokers were ousted by a number of buildings as their numbers grew, until they ended up in front of the Mills Building entrance on Broad Street.[23] The Mills building would be replaced by the Equitable Trust Building skyscraper in 1928.[29] The Stock Exchange Luncheon Club was a members-only dining club of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) founded on August 3, 1898 at 70 Broadway. It moved to the New York Stock Exchange Building at 11 Wall Street in 1903.[30]

1900–1921: Curb market boom

[edit]

The Broad Exchange Building at 25 Broad Street was built in 1900 to provide office space for financial companies including Paine Webber.[31] At the time of its completion it was the largest office building in Manhattan.[32] In 1903, NYSE moved into new quarters at 18 Broad Street, between the corners of Wall Street and Exchange Place.[33]

In the mining boom of 1905 and 1906, the Curb market on Broad Street attracted some negative publicity for the "wholesale use of the Curb for swindling".[34] As of 1907, the curb brokers intentionally avoided organizing.[23] The curb brokers had been kicked out of the Mills Building front by 1907, and had moved to the pavement outside the Blair Building where cabbies lined up. There they were given a "little domain of asphalt" fenced off by the police on Broad Street between Exchange Place and Beaver Street, after Police Commissioner McAddo took office.[23] As of 1907, the curb market operated starting at 10'clock in the morning, each day except on Sundays, until a gong at 3 o'clock. Orders for the purchase and sale of securities were shouted down from the windows of nearby brokerages, with the execution of the sale then shouted back up to the brokerage.[23] The noise caused by the curb market led to a number of attempts to shut it down.[35] In August 1907, for example, a Wall Street lawyer sent an open letter to the newspapers and the police commissioner, begging for the New York Curb Market on Broad Street to be immediately abolished as a public nuisance. He argued the curb exchange served "no legitimate or beneficial purpose" and was a "gambling institution, pure and simple". He further cited laws relating to street use, arguing blocking the thoroughfare was illegal. The New York Times, reporting on the open letter, wrote that brokers informed of the letter "were not inclined to worry". The article described "their present ground on the broad asphalt in front of 40 Broad Street, south of the Exchange Place, is the first haven of which they have had anything like indisputed possession."[23]

In 1908, the New York Curb Market Agency was established, which developed appropriate trading rules for curbstone brokers[36] under "curb agent" E. S. Mendels.[37] In 1910, Mendels testified before the Wall Street Investigating Committee on behalf of the curb brokers, when an attempt was made to dislodge them from Broad Street.[38] In 1908, 70 Broad Street, between Marketfield and Beaver Street, became the American Bank Note Company Building, the headquarters of the American Bank Note Company.[39] Built in 1913,[40] 23 Wall Street or "The Corner", is an office building formerly owned by J.P. Morgan & Co. – later the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company – located at the southeast corner of Wall Street and Broad Street. So well known as the "House of Morgan" – that it was deemed unnecessary to mark the exterior with the Morgan name.[41]

In 1920, journalist Edwin C. Hill wrote that the curb exchange on lower Broad Street was a "roaring, swirling whirlpool" that "tears control of a gold-mine from an unlucky operator, then pauses to auction a puppy-dog. It is like nothing else under the astonishing sky that is its only roof." After a group of curb brokers formed a real estate company to design a building, Starrett & Van Vleck designed the new exchange building on Greenwich Street in Lower Manhattan between Thames and Rector, at 86 Trinity Place. It opened in 1921,[35] and the curbstone brokers moved indoors on June 27, 1921.[42][43]

1922–present

[edit]When the high-profile New York firm Edward M. Fuller & Company went bankrupt in 1922, it had offices at 50 Broad Street.[44] Next to the New York Stock Exchange,[45] in 1929, a new 50-story Continental Bank Building was announced at 30 Broad Street (location of the former 15-story Johnston Building) to house the Continental Bank and Trust Company and various brokers.[45][46] The building opened for occupancy on April 27, 1932.[47]

The now-famous sculpture Charging Bull was installed[48] on December 15, 1989 beneath a 60-foot (18 m) Christmas tree in the middle of Broad Street in front of the New York Stock Exchange as a Christmas gift to New Yorkers.[49] After NYSE officials called police,[49] it was later reinstalled two blocks south of the Exchange, in Bowling Green.[50]

In 2011, the New York City Opera moved its offices to 75 Broad Street in Lower Manhattan.[51][52] Some re-shooting for the film Money Monster took place in mid-January 2016 in New York City on William Street and Broad Street.[53] On December 10, 2018 was installed in front of the NYSE building the sculpture Fearless Girl.[54]

Description

[edit]North of Wall Street, Broad Street continues onto Nassau Street. The two southernmost skyscrapers in Manhattan are 1 New York Plaza, on the west side of Broad Street, and 125 Broad Street, on the east. The famous neo-Roman facade of the New York Stock Exchange Building and its main entrance is located on 18 Broad Street. Opposite it is the former J.P. Morgan headquarters at 23 Wall Street and 15 Broad Street, the latter of which has been converted into a luxury condominium.

Other buildings of note are the Broad Exchange Building at number 25, the Continental Bank Building at number 30, the Lee, Higginson & Company Bank Building at number 37, and the American Bank Note Company Building at number 70.

Notable buildings

[edit]

From north to south, notable buildings include:

- 23 Wall Street

- 15 Broad Street

- New York Stock Exchange Building at 18 Broad Street

- Broad Exchange Building at 25 Broad Street

- Continental Bank Building at 30 Broad Street

- Lee, Higginson & Company Bank Building at 37 Broad Street

- 45 Broad Street - proposed skyscraper

- American Bank Note Company Building at 70 Broad Street

- Millennium High School at 75 Broad Street

- Fraunces Tavern

- 1 New York Plaza

- 2 New York Plaza

Notable former buildings have included:

Transportation

[edit]The Broad Street station (J and Z trains) of the New York City Subway is located at the corner of Broad and Wall Streets.[55]

The downtown M15, M20 and M55 buses all run on Broad Street south of Water Street (uptown buses use Whitehall Street). The M15 SBS crosses on Water Street in both directions.

See also

[edit]- Marketfield Street

- William Street (Manhattan)

- List of early skyscrapers

- History of transportation in New York City

- Hard Hat Riot

- Peter Stuyvesant

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kadinsky, Sergey (2016). Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs. New York, NY: Countryman Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-58157-566-8.

- ^ a b Moscow, Henry (1978). The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. New York: Hagstrom Company. ISBN 978-0-8232-1275-0.

- ^ a b "Old buildings of New York City: With some notes regarding their origin and occupants". New York: Brentano's. 1907. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Suzy Maroon. The Supreme Court of the United States, New York and Charlottesville: Thomasson-Grant and Lickle (1996), p. 18. ISBN 0-9650308-0-6

- ^ Prime, Nathaniel Scudder (1845). A history of Long Island : from its first settlement by Europeans to the year 1845, with special reference to its ecclesiastical concerns ... unknown library. New York : R. Carter.

- ^ "Lovelace's Tavern: Early New York History, Under Foot". The Bowery Boys: New York History. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Baugher, Sherene; Wall, Diana Dizerega (1997). "Ancient and Modern United". In Jameson, John H. Jr. (ed.). Presenting Archaeology to the Public: Digging for Truths. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-7619-8909-7.

- ^ "Forgotten Tour 17, Lower Manhattan". Forgotten New York. July 2004. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Michelle Nevius; James Nevius (2009). Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. New York: Free Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4165-9393-5.

- ^ New York Mercury, November 13, 1752

- ^ "Heroes of Ground Zero. FDNY A History". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ "Southern District of New York 225th Anniversary". history.nysd.uscourts.gov. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Asbury Dickens, A Synoptical Index to the Laws and Treaties of the United States of America (1852), p. 386.

- ^ U.S. District Courts of New York, Legislative history, Federal Judicial Center. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- ^ Terry Golway, So Others Might Live: A History of New York's Bravest, Basic Books, 2002, pp. 80-84.

- ^ "The Great Fire -- Additional Particulars". New York Daily Tribune. July 22, 1845. page 2.

- ^ The Draft Riot In New York City 1863 Part III: The New York Draft Riot. From the History Box website.

- ^ a b Metropolitan Police: Their Services During Riot Week. Their Honorable Record. By David M. Barnes.

- ^ Foner, E. (1988). Reconstruction America's unfinished revolution, 1863-1877. The New American Nation series, p. 32, New York: Harper & Row

- ^ Asbury, Herbert. The Gangs of New York. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. (pg. 130–132) ISBN 1-56025-275-8

- ^ Sobel, Robert (April 13, 2018). The Curbstone Brokers: The Origins of the American Stock Exchange. Beard Books. ISBN 9781893122659. Retrieved April 13, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Asks Bingham to Oust Curb Brokers; Lawyer Allen Says Open-Air Exchange Is a Public Nuisance and Therefore Illegal. He Cites Many Decisions And Will Press His Contention -- Brokers Forced to Move Many Times Owing to Complaints". The New York Times. New York City, New York. August 17, 1907.

- ^ a b E. Wright, Robert (January 8, 2013). "The NYSE's Long History of Mergers and Rivalries". Bloomberg. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "The New Stock Exchange". The New York Times. February 22, 1877. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "The Ketchum Forgery; Additional Particulars Yesterday's Developments". The New York Times. August 18, 1865. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Mills Building". The New York Times. February 3, 1882. p. 8.

- ^ "34-Story, $12,000,000 Structure to Replace Mills Building, First Wall Street Skyscraper". The New York Times. January 16, 1925. p. 1.

- ^ Chase, W. Parker (1983) [1932]. New York, the Wonder City. New York: New York Bound. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-9608788-2-6. OCLC 9946323.

- ^ Edmonston, Peter (April 28, 2006). "Where Wall Street Meets to Eat, the Last Lunch". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ SWIG realty summary of building Archived October 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "in the Real Estate Field; Four Per Cent. Loan of $3,450,000 on Broad-Exchange Building -- Sale of 115th Street Properties -- Dealings by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. August 31, 1909. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Survey, New York" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2007.

- ^ ""Curb" Wars on Swindlers; Ready to Investigate Any Stock Brokers of Whom the Public Complains". The New York Times. New York City, New York. November 11, 1909. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ a b When Stocks Came in From the Cold (September 30, 2010). "Christopher Gray". The New York Times. New York City, New York.

- ^ http://abcnewspapers.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=11281[permanent dead link] New York Curb Market Association

- ^ "Mendels at the White Inquiry; Hughes Investigators Take Up Conditions in the Curb Market". The New York Times. New York City, New York. February 27, 1909. p. 13. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ "Father of the Curb Dead; Emanuel S. Mendels, Jr., Elevated Trade and Routed Dishonest Brokers". The New York Times. New York City, New York. October 18, 1911. p. 11. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.45, 133

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1., p.15

- ^ "23 Wall Street". Time. (September 24, 1923). accessed March 15, 2010.

- ^ Teall, John L. (2012). Financial Trading and Investing. Academic Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780123918802.

- ^ "Curb Market Opens Its $2,250,000 Home; Abandoning Street Trading, Members Dedicate New Quarters in Trinity Place". The New York Times. June 28, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "E.M. Fuller & Co. Fail". The New York Times. New York City, New York. June 28, 1922. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "City Investing Co. Buys Skyscraper in Broad St". The New York Times. May 20, 1943.

- ^ "Old Realty Records on Broad Street; Continental Bank Site Once Owned by Dutch Church – Almshouse There in 1659". The New York Times. October 25, 1931.

- ^ "Cushman & Wakefield, Inc.". International Directory of Company Histories. 2007.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ D. McFadden, Robert (December 16, 1989). "SoHo Gift to Wall St.: A 3½-Ton Bronze Bull". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Mcfadden, Robert D. (December 16, 1989). "SoHo Gift to Wall St.: A 3 1/2-Ton Bronze Bull". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ The Associated Press (December 20, 1989). "Wall St.'s Bronze Bull Moves 2 Blocks South". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (May 23, 2011). "City Opera Departure Brings Questions". The New York Times.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (December 6, 2011). "City Opera Leaving Lincoln Center". The New York Times.

- ^ "'Money Monster' reshoots happening in NYC this week". On Location Vacations. January 19, 2016. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Li, Yun (December 10, 2018). "'Fearless Girl' unveiled in front of NYSE, moved away from 'Charging Bull'". CNBC. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.