Yosemite National Park

| Yosemite National Park | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Tuolumne, Mariposa, Mono and Madera Counties, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Mariposa, California |

| Coordinates | 37°44′33″N 119°32′15″W / 37.74250°N 119.53750°W[2] |

| Area | 759,620 acres (3,074.1 km2)[3] |

| Established | October 1, 1890 |

| Visitors | 3,897,070 (in 2023)[4] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | nps |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, viii |

| Reference | 308 |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th Session) |

Yosemite National Park (/joʊˈsɛmɪti/ yoh-SEM-ih-tee[5]) is a national park of the United States in California.[6][7] It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service and covers 759,620 acres (1,187 sq mi; 3,074 km2)[3] in four counties – centered in Tuolumne and Mariposa, extending north and east to Mono and south to Madera. Designated a World Heritage Site in 1984, Yosemite is internationally recognized for its granite cliffs, waterfalls, clear streams, groves of giant sequoia, lakes, mountains, meadows, glaciers, and biological diversity.[8] Almost 95 percent of the park is designated wilderness.[9] Yosemite is one of the largest and least fragmented habitat blocks in the Sierra Nevada.

Its geology is characterized by granite and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and tilted to form its unique slopes, which increased the steepness of stream and river beds, forming deep, narrow canyons. About one million years ago glaciers formed at higher elevations. They moved downslope, cutting and sculpting the U-shaped Yosemite Valley.[8]

European American settlers first entered the valley in 1851. Other travelers entered earlier, but James D. Savage is credited with discovering the area that became Yosemite National Park.[10] Native Americans had inhabited the region for nearly 4,000 years, although humans may have first visited as long as 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.[11][12]

Yosemite was critical to the development of the concept of national parks. Galen Clark and others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Yosemite Grant of 1864 that declared Yosemite as federally preserved land.[13] In 1890, John Muir led a successful movement to motivate Congress to establish Yosemite Valley and its surrounding areas as a National Park. This helped pave the way for the National Park System.[13] Yosemite draws about four million visitors annually.[14] Most visitors spend the majority of their time in the valley's seven square miles (18 km2).[8] The park set a visitation record in 2016, surpassing five million visitors for the first time.[15] In 2023, the park saw nearly four million visitors.[16]

Toponym

[edit]The word Yosemite (derived from yohhe'meti, "they are killers" in Miwok) historically referred to the name that the Miwok gave to the Ahwahneechee People, the resident indigenous tribe.[17][18][19] Previously, the region had been called "Ahwahnee" ("big mouth") by its only indigenous inhabitants, the Ahwahneechee.[17] The term Yosemite in Miwok is easily confused with a similar term for "grizzly bear", and is still a common misconception.[17][20]

History

[edit]Ahwahneechee and the Mariposa Wars

[edit]The indigenous natives of Yosemite called themselves the Ahwahneechee, meaning "dwellers" in Ahwahnee.[21] The Ahwahneechee People were the only tribe that lived within the park boundaries, but other tribes lived in surrounding areas. Together they formed a larger Indigenous population in California, called the Southern Sierra Miwok.[22] They are related to the Northern Paiute and Mono tribes. Other tribes like the Central Sierra Miwoks and the Yokuts, who both lived in the San Joaquin Valley and central California, visited Yosemite to trade and intermarry.[23] This resulted in a blending of culture that helped preserve their presence in Yosemite after early American settlements and urban development threatened their survival.[22] Vegetation and game in the region were similar to modern times; acorns were a dietary staple, as well as other seeds and plants, salmon and deer.[22]

The 1848–1855 California Gold Rush was a major event impacting the native population. It drew more than 90,000 European Americans to the area in 1849, causing competition for resources between gold miners and residents.[24] About 70 years before the Gold Rush, the indigenous population was estimated to be 300,000, quickly dropping to 150,000, and just ten years later, only about 50,000 remained.[12] The reasons for such a decline included disease, birth rate decreases, starvation, and conflict. The conflict in Yosemite, which is known as the Mariposa War, was part of the California genocide, which was the systemic killing of indigenous peoples throughout the State between the 1840s and 1870s.[25] It started in December 1850 when California funded a state militia to drive Native people from contested territory to suppress Native American resistance to the European American influx.[26]

Yosemite tribes often stole from settlers and miners, sometimes killing them, in retribution for the extermination/domestication of their people, and loss of their lands and resources.[12] The War and formation of the Mariposa Battalion was partially the result of a single incident involving James Savage, a Fresno trader whose trading post was attacked in December, 1850. After the incident, Savage rallied other miners and gained the support of local officials to pursue a war against the Natives. He was appointed United States Army Major and leader of the Mariposa Battalion in the beginning of 1851.[12] He and Captain John Boling were responsible for pursuing the Ahwahneechee people, led by Chief Tenaya and driving them west, and out of Yosemite.[27][12] In March 1851 under Savage's command, the Mariposa Battalion captured about 70 Ahwahneechee and planned to take them to a reservation in Fresno, but they escaped. Later in May, under the command of Boling, the battalion captured 35 Ahwahneechee, including Chief Tenaya, and marched them to the reservation. Most were allowed to eventually leave and the rest escaped.[12] Tenaya and others fled across the Sierra Nevada and settled with the Mono Lake Paiutes. Tenaya and some of his companions were ultimately killed in 1853 either over stealing horses or a gambling conflict. The survivors of Tenaya's group and other Ahwahneechee were absorbed into the Mono Lake Paiute tribe.[12][28][29]

Accounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor Lafayette Bunnell, who later wrote about his awestruck impressions of the valley in The Discovery of the Yosemite. Bunnell is credited with naming Yosemite Valley, based on his interviews with Chief Tenaya. Bunnell wrote that Chief Tenaya was the founder of the Ahwahnee colony.[30] Bunnell falsely believed that the word "Yosemite" meant "full-grown grizzly bear".[31]

Indigenous peoples' continuing presence

[edit]

After the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite Ahwahneechee tribe members there were forced to relocate to a village constructed in 1851 by the state government.[12] They learned to live within this camp and their limited rights, adapting to the changed environment by entering the tourism industry through employment and small businesses, manufacturing and selling goods and providing services.[22] In 1953, the National Park Service banned all non-employee Natives from residing in the Park and evicted the non-employees who had residence. In 1969, with only a few families left in the Park, the National Park Service evicted the remaining Native people living within the Park (all Park employees and their families) to a government housing area for park employees and destroyed the village as part of a fire-fighting exercise.[32][26] A reconstructed "Indian Village of Ahwahnee" sits behind the Yosemite Museum, located next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center.[33][34][35]

By the late 19th century, the population of all native inhabitants in Yosemite was difficult to determine, estimates ranged from thirty to several hundred. The Ahwahneechee people and their descendants were hard to identify.[12] The last full-blooded Ahwahneechee died in 1931. Her name was Totuya, or Maria Lebrado. She was the granddaughter of Chief Tenaya and one of many forced out of her ancestral homelands.[12][26] The Ahwahneechee live through the memory of their descendants, their fellow Yosemite Natives, and through the Yosemite exhibit in the Smithsonian and the Yosemite Museum.[12] As a method of self-preservation and resilience, the Indigenous people of California proposed treaties in 1851 and 1852 that would have established land reservations for them, but Congress refused to ratify them.[12] The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation is seeking tribal sovereignty and federal recognition.[26][36] The National Park Service created policies to protect sacred sites and allow Native People to return to their homelands and use National Park resources.[36][37]

Early tourists

[edit]In 1855, entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings, artist Thomas Ayres and two others were the first tourists to visit.[38] Hutchings and Ayres were responsible for much of Yosemite's earliest publicity, writing articles and special issues about the valley.[39] Ayres' style was detailed with exaggerated angularity. His works and written accounts were distributed nationally, and an exhibition of his drawings was held in New York City. Hutchings' publicity efforts between 1855 and 1860 increased tourism to Yosemite.[40] Natives supported the growing tourism industry by working as laborers or maids. Later, they performed dances for tourists, acted as guides, and sold handcrafted goods, notably woven baskets.[22] The Indian village and its peoples fascinated visitors, especially James Hutchings who advocated for Yosemite tourism. He and others considered the indigenous presence to be one of Yosemite's greatest attractions.[22]

Wawona was an early Indian encampment for Nuchu and Ahwahneechee people who were captured and relocated to a reservation on the Fresno River by Savage and the Mariposa Battalion in March 1851.[41] Galen Clark discovered the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoia in Wawona in 1857. He had simple lodgings and roads built. In 1879, the Wawona Hotel was built to serve tourists visiting Mariposa Grove.[42] As tourism increased, so did the number of trails and hotels to build on it.[43]

The Wawona Tree, also known as the Tunnel Tree, was a giant sequoia that grew in the Mariposa Grove. It was 234 feet (71 m) tall, and was 90 ft (27 m) in circumference. When a carriage-wide tunnel was cut through the tree in 1881, it became even more popular as a tourist photo attraction. Carriages and automobiles traversed the road that passed through the tree. The tree was permanently weakened by the tunnel, and it fell in 1969 under a heavy load of snow. It was estimated to have been 2,100 years old.[44]

Yosemite's first concession was established in 1884 when John Degnan and his wife established a bakery and store.[45] In 1916, the National Park Service granted a 20-year concession to the Desmond Park Service Company. It bought out or built hotels, stores, camps, a dairy, a garage, and other park facilities.[46] The Hotel Del Portal was completed in 1908 by a subsidiary of the Yosemite Valley Railroad. It was located at El Portal, California just outside of Yosemite.[47][48]

The Curry Company started in 1899, led by David and Jennie Curry to provide concessions. They founded Camp Curry, now Curry Village.[49]

Park service administrators felt that limiting the number of concessionaires in the park would be more financially sound. The Curry Company and its rival, the Yosemite National Park Company, were forced to merge in 1925 to form the Yosemite Park & Curry Company (YP&CC).[50] The company built the Ahwahnee Hotel in 1926–27.[51]

Yosemite Grant

[edit]Concerned by the impact of commercial interests, citizens including Galen Clark and Senator John Conness advocated protection for the area.[52] The 38th United States Congress passed legislation that was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864, creating the Yosemite Grant.[53][54] This is the first time land was set aside specifically for preservation and public use by the U.S. government, and set a precedent for the 1872 creation of Yellowstone national park, the nation's first.[13] Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove were ceded to California as a state park, and a board of commissioners was established two years later.[55]

Galen Clark was appointed by the commission as the Grant's first guardian, but neither Clark nor the commissioners had the authority to evict homesteaders (which included Hutchings).[53] The issue was not settled until 1872 when the homesteader land holdings were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court.[56] Clark and the commissioners were ousted in a dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1880.[57] The two Supreme Court decisions affecting management of the Yosemite Grant are considered precedents in land management law.[58] Hutchings became the new park guardian.[59]

Tourist access to the park improved, and conditions in the Valley became more hospitable. Tourism significantly increased after the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, while the long horseback ride to reach the area was a deterrent.[53] Three stagecoach roads were built in the mid-1870s to provide better access for the growing number of visitors.[60]

John Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist and explorer. Muir's leadership ensured that many National Parks were left untouched, including Yosemite.[61]

Muir wrote articles popularizing the area and increasing scientific interest in it. Muir was one of the first to theorize that the major landforms in Yosemite Valley were created by alpine glaciers, bucking established scientists such as Josiah Whitney.[59] Muir wrote scientific papers on the area's biology. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted emphasized the importance of conservation of Yosemite Valley.[62]

Increased protection efforts

[edit]Overgrazing of meadows (especially by sheep), logging of giant sequoia, and other damage led Muir to become an advocate for further protection. Muir convinced prominent guests of the importance of putting the area under federal protection. One such guest was Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine. Muir and Johnson lobbied Congress for the Act that created Yosemite National Park on October 1, 1890.[63] The State of California, however, retained control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove. Muir's writings raised awareness about the damage caused by sheep grazing, and he actively campaigned to virtually eliminate grazing from the Yosemite's high-country.[64]

The newly created national park came under the jurisdiction of the United States Army's Troop I of the 4th Cavalry on May 19, 1891, which set up camp in Wawona with Captain Abram Epperson Wood as acting superintendent.[63] By the late 1890s, sheep grazing was no longer a problem, and the Army made other improvements. However, the cavalry could not intervene to ease the worsening conditions. From 1899 to 1913, cavalry regiments of the Western Department, including the all Black 9th Cavalry (known as the "Buffalo Soldiers") and the 1st Cavalry, stationed two troops at Yosemite.

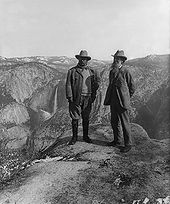

Muir and his Sierra Club continued to lobby the government and influential people for the creation of a unified Yosemite National Park. In May 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt camped with Muir near Glacier Point for three days. On that trip, Muir convinced Roosevelt to take control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove away from California and return it to the federal government. In 1906, Roosevelt signed a bill that shifted control.[65]

National Park Service

[edit]The National Park Service (NPS) was formed in 1916, and Yosemite was transferred to that agency's jurisdiction. Tuolumne Meadows Lodge, Tioga Pass Road, and campgrounds at Tenaya and Merced lakes were also completed in 1916.[66] Automobiles started to enter the park in ever-increasing numbers following the opening of all-weather highways to the park. The Yosemite Museum was founded in 1926 through the efforts of Ansel Franklin Hall.[67] In the 1920s, the museum featured Native Americans practicing traditional crafts, and many Southern Sierra Miwok continued to live in Yosemite Valley until they were evicted from the park in the 1960s.[68] Although the NPS helped create a museum that included Native American culture, its early actions and organizational values were dismissive of Yosemite Natives and the Ahwahneechee.[12] NPS in the early 20th century criticized and restricted the expression of indigenous culture and behavior. For example, park officials penalized Natives for playing games and drinking during the Indian Field Days of 1924.[22] In 1929, Park Superintendent Charles G. Thomson concluded that the Indian village was aesthetically unpleasant and was limiting white settler development and ordered the camp to be burned down.[12] In 1969, many Native residents left in search of work as a result of the decline in tourism. NPS demolished their empty houses, evicted the remaining residents, and destroyed the entire village.[12] This was the last Indigenous settlement within the park.[12][26]

In 1903, a dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley in the northwestern region of the park was proposed. Its purpose was to provide water and hydroelectric power to San Francisco. Muir and the Sierra Club opposed the project, while others, including Gifford Pinchot, supported it.[69] In 1913, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was approved via passage of the Raker Act.[70]

In 1918, Clare Marie Hodges was hired as the first female Park Ranger in Yosemite.[71] Following Hodges in 1921, Enid Michael was hired as a seasonal Park Ranger[71] and continued to serve in that position for 20 years.[71]

In 1937, conservationist Rosalie Edge, head of the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), successfully lobbied Congress to purchase about 8,000 acres (3,200 ha) of old-growth sugar pines on the perimeter of Yosemite National Park that were to be logged.[72]

By 1968, traffic congestion and parking in Yosemite Valley during the summer months has become a concern.[73] NPS reduced artificial inducements to visit the park, such as the Firefall, in which red-hot embers were pushed off a cliff near Glacier Point at night.[74]

In 1984, preservationists persuaded Congress to designate 677,600 acres (274,200 ha), or about 89 percent of the park, as the Yosemite Wilderness. As a wilderness area, it would be preserved in its natural state with humans being only temporary visitors.[75]

In 2016, The Trust for Public Land (TPL) purchased Ackerson Meadow, a 400-acre tract (160 ha) on the western edge of the park for $2.3 million. Ackerson Meadow was originally included in the proposed 1890 park boundary, but never acquired by the federal government. The purchase and donation of the meadow was made possible through a cooperative effort by TPL, NPS, and Yosemite Conservancy. On September 7, 2016, NPS accepted the donation of the land, making the meadow the largest addition to Yosemite since 1949.[76] With extensive erosion from years of cattle ranching , the land is being transformed back into a healthy meadow.[77]

Geography

[edit]

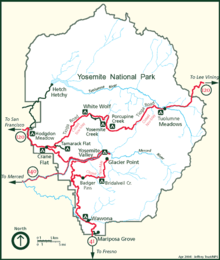

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the Hoover Wilderness to the northeast, and the Emigrant Wilderness to the north.

The 1,189 sq mi (3,080 km2) park contains thousands of lakes and ponds, 1,600 miles (2,600 km) of streams, 800 miles (1,300 km) of hiking trails, and 350 miles (560 km) of roads.[78] Two federally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers, the Merced and the Tuolumne, begin within Yosemite's borders and flow westward through the Sierra foothills into the Central Valley of California.

Rocks and erosion

[edit]

Almost all of the landforms are cut from the granitic rock of the Sierra Nevada Batholith (a batholith is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock that formed deep below the surface).[79] About five percent of the park's landforms (mostly in its eastern margin near Mount Dana) are metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks.[80] These roof pendants once formed the roof over the underlying granitic magma.[81]

Erosion acting upon different types of uplift-generated joint and fracture systems is responsible for producing the valleys, canyons, domes, and other features. These joints and fracture systems do not move, and are therefore not faults.[82] Spacing between joints is controlled by the amount of silica in the granite and granodiorite rocks; more silica tends to form a more resistant rock, resulting in larger spaces between joints and fractures.[83]

Pillars and columns, such as Washington Column and Lost Arrow, are generated by cross joints. Erosion acting on master joints is responsible for shaping valleys and later canyons.[83] The single most erosive force over the last few million years has been large alpine glaciers, which turned the previously V-shaped river-cut valleys into U-shaped glacial-cut canyons (such as Yosemite Valley and Hetch Hetchy Valley). Exfoliation (caused by the tendency of crystals in plutonic rocks to expand at the surface) acting on granitic rock with widely spaced joints is responsible for producing domes such as Half Dome and North Dome and inset arches like Royal Arches.[84]

Popular features

[edit]

Yosemite Valley represents only one percent of the park area. The Tunnel View gives a view of the valley. El Capitan is a prominent granite cliff that looms over the valley, and is a rock climbing favorite because of its sheer size, diverse climbing routes, and year-round accessibility. Granite domes such as Sentinel Dome and Half Dome rise 3,000 and 4,800 feet (910 and 1,460 m), respectively, above the valley floor. The park contains dozens of other granite domes.[85]

The high country of Yosemite contains other important features such as Tuolumne Meadows, Dana Meadows, the Clark Range, the Cathedral Range, and the Kuna Crest. The Sierra Crest and the Pacific Crest Trail run through Yosemite. Mount Dana and Mount Gibbs are peaks of red metamorphic rock. Granite peaks include Mount Conness, Cathedral Peak, and Matterhorn Peak. Mount Lyell is the highest point in the park, standing at 13,120 feet (4,000 m). The Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in the park and one of the few remaining in the Sierra.[86]

The park has three groves of ancient giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) trees; the Mariposa Grove (200 trees), the Tuolumne Grove (25 trees), and the Merced Grove (20 trees).[87] This species grows larger in volume than any other and is one of the tallest and longest-lived.[88]

Water and ice

[edit]

The Tuolumne and Merced River systems originate along the crest of the Sierra in the park and have carved river canyons 3,000 to 4,000 feet (910 to 1,220 m) deep. The Tuolumne River drains the entire northern portion of the park, an area of approximately 680 square miles (1,800 km2). The Merced River begins in the park's southern peaks, primarily the Cathedral and Clark Ranges, and drains an area of approximately 511 square miles (1,320 km2).[89]

Hydrologic processes, including glaciation, flooding, and fluvial geomorphic response, have been fundamental in creating park landforms.[89] The park contains approximately 3,200 lakes (greater than 100 m2), two reservoirs, and 1,700 miles (2,700 km) of streams.[90] Wetlands flourish in valley bottoms throughout the park, and are often hydrologically linked to nearby lakes and rivers through seasonal flooding and groundwater. Meadow habitats, distributed at elevations from 3,000 to 11,000 feet (910 to 3,350 m) in the park, are generally wetlands, as are the riparian habitats found on the banks of Yosemite's watercourses.[91]

Yosemite is famous for its high concentration of waterfalls in a small area. Numerous sheer drops, glacial steps and hanging valleys in the park feature spectacular cascades, especially during April, May, and June (as the snow melts). Located in Yosemite Valley, Yosemite Falls is the fourth tallest waterfall in North America at 2,425 feet (739 m) according to the World Waterfall Database.[92] Also in the valley is the much lower volume Ribbon Falls, which has the highest single vertical drop, 1,612 feet (491 m).[88] Perhaps the most prominent of the valley waterfalls is Bridalveil Fall. Wapama Falls in Hetch Hetchy Valley is another notable waterfall. Hundreds of ephemeral waterfalls become active in the park after heavy rains or melting snowpack.[93]

Park glaciers are relatively small and occupy areas that are in almost permanent shade, such as north- and northeast-facing cirques. Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in Yosemite (the Palisades Glaciers are the largest in the Sierra Nevada) and covers 160 acres (65 ha).[94] None of the Yosemite glaciers are a remnant of the Ice Age alpine glaciers responsible for sculpting the Yosemite landscape. Instead, they were formed during one of the neoglacial episodes that have occurred since the thawing of the Ice Age (such as the Little Ice Age).[87] Many Yosemite glaciers have disappeared, such as the Black Mountain Glacier that was marked in 1871 and had gone by the mid-1980s.[95] Yosemite's final two glaciers – the Lyell and Maclure glaciers – have receded over the last 100 years and are expected to disappear as a result of climate change.[96][97]

Climate

[edit]

Yosemite has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), meaning most precipitation falls during the mild winter, and the other seasons are nearly dry (less than three percent of precipitation falls during the long, hot summers). Because of orographic lift, precipitation increases with elevation up to 8,000 feet (2,400 m) where it slowly decreases to the crest. Precipitation amounts vary from 36 inches (910 mm) at 4,000 feet (1,200 m) elevation to 50 inches (1,300 mm) at 8,600 feet (2,600 m). Snow does not typically accumulate until November in the high country. It deepens into March or early April.[98]

Mean daily temperatures range from 25 °F (−4 °C) to 53 °F (12 °C) at Tuolumne Meadows at 8,600 feet (2,600 m). At the Wawona Entrance (elevation 5,130 feet or 1,560 metres), mean daily temperature ranges from 36 to 67 °F (2 to 19 °C). At the lower elevations below 5,000 feet (1,500 m), temperatures are hotter; the mean daily high temperature at Yosemite Valley (elevation 3,966 feet or 1,209 metres) varies from 46 to 90 °F (8 to 32 °C). At elevations above 8,000 feet (2,400 m), the hot, dry summer temperatures are moderated by frequent summer thunderstorms, along with snow that can persist into July. The combination of dry vegetation, low relative humidity, and thunderstorms results in frequent lightning-caused fires as well.[98]

At park headquarters (elevation 4,018 ft or 1,225 m), January averages 38.0 °F (3.3 °C), while July averages 73.3 °F (22.9 °C). In summer the nights are much cooler than the days. An average of 45.5 days have highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and an average of 105.6 nights with freezing temperatures. Freezing temperatures have been recorded in every month of the year. The record high temperature was 112 °F (44 °C) on July 22 and July 24, 1915, while the record low temperature was −7 °F (−22 °C) on January 1, 2009. Average annual precipitation is nearly 37 inches (940 mm), falling on 67 days. The wettest year was 1983 with 66.06 inches (1,678 mm) and the driest year was 1976 with 14.84 inches (377 mm). The most precipitation in one month was 29.61 inches (752 mm) in December 1955 and the most in one day was 6.92 inches (176 mm) on December 23, 1955. Average annual snowfall is 39.4 inches (1.00 m). The snowiest winter was 1948–1949 with 176.5 inches (4.48 m). The most snow in one month was 175.0 inches (4.45 m) in January 1993.

| Climate data for Yosemite Park Headquarters, California, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1905–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

82 (28) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

103 (39) |

112 (44) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

73 (23) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.7 (14.8) |

64.2 (17.9) |

70.4 (21.3) |

77.0 (25.0) |

83.3 (28.5) |

91.3 (32.9) |

97.4 (36.3) |

97.5 (36.4) |

93.7 (34.3) |

85.1 (29.5) |

70.9 (21.6) |

59.3 (15.2) |

99.1 (37.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 47.5 (8.6) |

51.2 (10.7) |

56.7 (13.7) |

63.1 (17.3) |

70.5 (21.4) |

80.5 (26.9) |

89.2 (31.8) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.0 (28.3) |

70.9 (21.6) |

56.0 (13.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

67.0 (19.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 38.0 (3.3) |

40.7 (4.8) |

45.1 (7.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

57.5 (14.2) |

65.8 (18.8) |

73.3 (22.9) |

72.9 (22.7) |

67.2 (19.6) |

56.1 (13.4) |

44.3 (6.8) |

36.8 (2.7) |

54.0 (12.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.5 (−1.9) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

33.5 (0.8) |

37.6 (3.1) |

44.5 (6.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

57.4 (14.1) |

56.8 (13.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

41.3 (5.2) |

32.5 (0.3) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

41.0 (5.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

40.8 (4.9) |

49.8 (9.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

42.0 (5.6) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

20.7 (−6.3) |

15.7 (−9.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

1 (−17) |

9 (−13) |

12 (−11) |

15 (−9) |

22 (−6) |

32 (0) |

32 (0) |

24 (−4) |

19 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−1 (−18) |

−7 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.98 (177) |

6.49 (165) |

5.47 (139) |

3.17 (81) |

1.92 (49) |

0.46 (12) |

0.29 (7.4) |

0.16 (4.1) |

0.40 (10) |

1.56 (40) |

4.05 (103) |

5.60 (142) |

36.55 (928) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 16.8 (43) |

4.2 (11) |

5.2 (13) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.4 (8.6) |

5.1 (13) |

35.5 (90.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.9 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 8.5 | 66.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 7.8 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[99][100][101] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[102] | |||||||||||||

Geology

[edit]

Tectonic and volcanic activity

[edit]The location of the park was a passive continental margin during the Precambrian and early Paleozoic.[103] Sediment was derived from continental sources and was deposited in shallow water. These rocks became deformed and metamorphosed.[104][105]

Heat generated from the Farallon Plate subducting below the North American Plate led to the creation of an island arc of volcanoes on the west coast of proto-North America between the late Devonian and Permian periods.[103] Material accreted onto the western edge of North America, and mountains were raised to the east in Nevada.[106]

The first phase of regional plutonism started 210 million years ago in the late Triassic and continued throughout the Jurassic to about 150 million years before present (BP), which led to the creation of the Sierra Nevada Batholith.[79] The resulting rocks were mostly granitic in composition and lay about 6 miles (9.7 km) below the surface.[107] Around the same time, the Nevadan orogeny built the Nevadan mountain range (also called the Ancestral Sierra Nevada) to a height of 15,000 feet (4,600 m).

The second major pluton emplacement phase lasted from about 120 million to 80 million years ago during the Cretaceous.[79] This was part of the Sevier orogeny.[108]

Starting 20 million years ago (in the Cenozoic) and lasting until 5 million years ago, a now-extinct extension of Cascade Range volcanoes erupted, bringing large amounts of igneous material in the area. These igneous deposits blanketed the region north of the Yosemite region. Volcanic activity persisted past 5 million years BP east of the current park borders in the Mono Lake and Long Valley areas.[109]

Uplift and erosion

[edit]

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the gradient of western-flowing streams.[110] The streams consequently ran faster and thus cut their valleys more quickly. Additional uplift occurred when major faults developed to the east, forming Owens Valley from Basin and Range-associated extensional forces. Sierra uplift accelerated again about two million years ago during the Pleistocene.[111]

The uplifting and increased erosion exposed granitic rocks to surface pressures, resulting in exfoliation (responsible for the rounded shape of the many domes in the park) and mass wasting following the numerous fracture joint planes (cracks; especially vertical ones) in the now solidified plutons.[84] Pleistocene glaciers further accelerated this process, while glacial meltwater transported the resulting talus and till from valley floors.[112]

Numerous vertical joint planes controlled where and how fast erosion took place. Most of these long, linear and very deep cracks trend northeast or northwest and form parallel, often regularly spaced sets.[112]

Glacial sculpting

[edit]

A series of glaciations further modified the region starting about 2 to 3 million years ago and ending sometime around 10,000 BP. At least four major glaciations occurred in the Sierra, locally called the Sherwin (also called the pre-Tahoe), Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga.[110] The Sherwin glaciers were the largest, filling Yosemite and other valleys, while later stages produced much smaller glaciers. A Sherwin-age glacier was almost surely responsible for the major excavation and shaping of Yosemite Valley and other canyons in the area.[113]

Glacial systems reached depths of up to 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and left their marks. The longest glacier ran down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River for 60 miles (97 km), passing well beyond Hetch Hetchy Valley. Merced Glacier flowed out of Yosemite Valley and into the Merced River Gorge. Lee Vining Glacier carved Lee Vining Canyon and emptied into Lake Russel (the much-enlarged ice age version of Mono Lake). Only the highest peaks, such as Mount Dana and Mount Conness, were not covered by glaciers. Retreating glaciers often left recessional moraines that impounded lakes such as the 5.5 miles (9 km) long Lake Yosemite (a shallow lake that periodically covered much of the floor of Yosemite Valley).[114]

Ecology

[edit]Habitats

[edit]

The park has an elevation range from 2,127 to 13,114 feet (648 to 3,997 m) and contains five major vegetation zones: chaparral and oak woodland, lower montane forest, upper montane forest, subalpine zone, and alpine. Of California's 7,000 plant species, approximately 50 percent occur in the Sierra Nevada and more than 20 percent within the park. The park contains suitable habitat for more than 160 rare plants, with rare local geologic formations and unique soils characterizing the restricted ranges many of these plants occupy.[8]

With its scrubby sun-baked chaparral, stately groves of pine, fir, and sequoia, and expanses of alpine woodlands and meadows, Yosemite National Park preserves a Sierra landscape as it prevailed before Euro-American settlement.[115] In contrast to surrounding lands, which have been significantly altered by logging, the park contains some 225,510 acres (91,260 ha) of old-growth forest.[116] Taken together, the park's varied habitats support over 250 species of vertebrates, which include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[117]

Yosemite's western boundary has habitats dominated by mixed coniferous forests of ponderosa pine, sugar pine, incense cedar, white fir, Douglas fir, and a few stands of giant sequoia, interspersed by areas of black oak and canyon live oak. These habitats support relatively high wildlife diversity. Wildlife include black bear, coyote, raccoon, mountain kingsnake, Gilbert's skink, white-headed woodpecker, bobcat, river otter, gray fox, red fox, brown creeper, two species of skunk, cougar, spotted owl, and bats.[117]

At higher elevation, the coniferous forests become purer stands of red fir, western white pine, Jeffrey pine, lodgepole pine, and the occasional foxtail pine. Fewer wildlife species tend to be found in these habitats, because of their higher elevation and lower complexity. Animals include golden-mantled ground squirrel, chickaree, fisher, Steller's jay, hermit thrush, and American goshawk. Reptiles are not common, but include rubber boa, western fence lizard, and northern alligator lizard.[117]

As the landscape rises, trees become smaller and more sparse, with stands broken by areas of exposed granite. These include lodgepole pine, whitebark pine, and mountain hemlock that, at highest elevations, give way to vast expanses of granite as treeline is reached. The climate in these habitats is harsh and the growing season is short, but species such as pika, yellow-bellied marmot, white-tailed jackrabbit, Clark's nutcracker, and black rosy finch are adapted to these conditions. Treeless alpine habitats are favored by Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep. This species is found in the Yosemite area only around Tioga Pass, where a small, reintroduced population exists.[117]

At a variety of elevations, meadows provide important habitat. Animals come to feed on the green grasses and use the flowing and standing water found in many meadows. Predators follow these animals. The interface between meadow and forest is favored by many animal species because of the proximity of open areas for foraging and cover for protection. Species that are highly dependent upon meadow habitat include great grey owl, willow flycatcher, Yosemite toad, and mountain beaver.[117]

Management issues

[edit]

The black bears of Yosemite were once famous for breaking into parked cars to steal food. They were an encouraged tourist sight for many years at the park's garbage dumps, where they congregated to eat garbage, and tourists gathered to photograph them. Increasing bear/human encounters and increasing property damage led to an aggressive campaign to discourage bears from interacting with people and their stuff. The open-air dumps were closed; trash receptacles were replaced with bear-proof receptacles; campgrounds were equipped with bear-proof food lockers so that people would not leave food in their vehicles. Because bears who show aggression towards people usually are destroyed, park personnel have come up with innovative ways to lead bears to associate humans and their property with experiences such as getting hit with a rubber bullet. As of 2001[update], about 30 bears a year were captured and ear-tagged and their DNA sampled so that, when bear damage occurs, rangers can ascertain which bear was causing the problem.[118][needs update]

Despite the richness of high-quality habitats in Yosemite, the brown bear, California condor, and least Bell's vireo have become extinct in the park within historical time,[119] and another 37 species currently have special status under either California or federal endangered species legislation. The most serious current threats include loss of a natural fire regime, exotic species, air pollution, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. On a more local basis, factors such as road kills and the availability of human food have affected some wildlife species.[120][121]

Yosemite National Park has documented the presence of more than 130 non-native plant species within park boundaries. They were introduced into Yosemite following the migration of early Euro-American settlers in the late 1850s. Natural and human-caused disturbances, such as wildland fires and construction activities, have contributed to a rapid increase in the spread of non-native plants. Some of these species invade and displace the native plant communities, impacting park resources. Non-native plants can bring about significant ecosystem changes by altering native plant communities and the processes that support them. Some non-native species may cause an increase in fire frequency or increase the available soil nitrogen that allow other non-native plants to establish. Many non-native species, such as yellow star thistle (Centaurea solstitialis), are able to produce a long tap root that allows them to out-compete the native plants for available water.[122]

Bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), and Klamath weed (Hypericum perforatum) have been identified as noxious pests in Yosemite since the 1940s. More recently recognized species are yellow star thistle (Centaurea solstitialis), sweet clover (Melilot spp.), Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus), cut-leaved blackberry (Rubus laciniatus) and large periwinkle (Vinca major).[122]

Increasing ozone pollution causes tissue damage to sequoia trees, making them more vulnerable to insect infestation and disease. Since the cones of these trees require fire-touched soil to germinate, historic fire suppression has reduced their ability to reproduce. Planned prescribed fires may help the germination issue.[123]

Wildfires

[edit]

Indigenous residents intentionally set small fires in the early 1860s and before to clear the ground of brush as part as their farming practices.[22] These fires are comparable to contemporary practices such as controlled burns that are done by the U.S. Forest Service and others. Although it was not their primary reason, Yosemite Natives helped preserve biodiversity and resilience by lighting these small fires. Native Americans used fire as an early wildlife management tool to keep certain lands clear, resulting in more food for large animals and decreasing the chance of large forest fires which that now devastate forest ecosystems.[124] Some early uncontrolled forest fires were set accidentally by the militia group led by Major John Savage when the group burned down the Ahwahneechee camp in an attempt to expel them. The house fires eventually spread to a large section of the forest and the militia group ended up having to abandon their raid to save their own camp from the conflagration.[124]

Forest fires clear the park of dead vegetation, making way for new growth.[125] Small fires damage the income generated by tourism. During late July and early August, 2018, the Valley and other sections of the park, temporarily closed due to the Ferguson Fire at its western boundary.[126] The closing was the largest in almost thirty years.[127]

Activities

[edit]

Public access

[edit]Yosemite National Park is open year-round, though certain roads close during snowy months, usually from November through May or June.[128] Certain trails also close during winter, including The 4-Mile Trail and part of The Mist Trail.[129]

Traffic congestion in the valley is heavy during peak summer season (June to August) and a free shuttle bus system operates in the valley. Parking in the valley during the summer is often full.[130] Transit options are available from Fresno and Merced.[131]

The natural and cultural history of Yosemite Valley is presented at the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center, the adjoining Yosemite Museum, and the Nature Center at Happy Isles. The parks' two National Historic Landmarks are the Sierra Club's LeConte Memorial Lodge (Yosemite's first public visitor center), and the Ahwahnee Hotel. Camp 4 is on the National Register of Historic Places.[132]

Hiking

[edit]

Over 800 miles (1,300 km) of trails are available to hikers[8]—everything from an easy stroll to a challenging mountain hike, or backpacking trips. The popular Half Dome hike to the summit of Half Dome requires a permit whenever the cables are up (usually from Memorial Day weekend to Columbus Day).[133] A maximum of 300 hikers, selected by lottery, are permitted to advance beyond the base of the subdome each day, including 225 day hikers and 75 backpackers.[134]

The park can be divided into five sections—Yosemite Valley, Wawona/Mariposa Grove/Glacier Point, Tuolumne Meadows, Hetch Hetchy, and Crane Flat/White Wolf.[135] Numerous books describe park trails, while the National Park Service provides free information.

Between late spring and early fall, much of the park can be accessed for backpacking trips. All overnight trips into the back country require a wilderness permit[136] and most require approved bear-resistant food storage.[137]

Driving

[edit]While some locations in Yosemite are accessible only on foot, other locations can be reached via road. The most famous road is Tioga Road.[138]

Bicycles are allowed on the roads, but only 12 miles (19 km) of paved off-road trails are available in Yosemite Valley itself; mountain biking is not allowed.[139]

Climbing

[edit]

Rock climbing is an important part of Yosemite.[140] In particular the valley is surrounded by summits such as Half Dome and El Capitan. Camp 4 is a walk-in campground in the Valley that was instrumental in the development of rock climbing as a sport, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[141] Climbers can generally be spotted in the snow-free months on anything from ten-foot-high (3 m) boulders to the 3,300-foot (1.0 km) face of El Capitan. Classes on rock climbing are offered there.

Tuolumne Meadows is well known for rock and mountain climbing.

Winter activities

[edit]

Away from the Valley, the park is snowed in during the winter months, with many roads closed. Downhill skiing is available at the Badger Pass Ski Area—the oldest downhill skiing area in California, operating from mid-December through early April.[142] Much of the park is open to cross-country skiing and snowshoeing, and backcountry ski huts are available.[143][144] Wilderness permits are required for backcountry overnight ski trips.[136]

The Bracebridge dinner is an annual holiday event, held since 1927 at the Ahwahnee Hotel, inspired by Washington Irving's descriptions of Squire Bracebridge and English Christmas traditions of the 18th century in his Sketch Book. Between 1929 and 1973, the show was organized by Ansel Adams.[145]

Other

[edit]Yosemite has 13 official campgrounds.[146]

Bicycle rentals are available from spring through fall. Over 12 miles (19 km) of paved bike paths are available in Yosemite Valley. In addition, bicyclists can ride on roads. Helmets are required for children under 18 years of age. Off-trail riding and mountain biking are not permitted in the park.[147]

Water activities are plentiful during warmer months. Rafting can be done through the valley on the Merced River from late May to July.[148] Swimming pools are available at Yosemite Lodge and Curry Village.

Horsetail Fall

[edit]Horsetail Fall flows over the eastern edge of El Capitan. This small waterfall usually flows only during winter and is easy to miss. On rare occasions during mid- to late February, it can glow orange when backlit by sunset. This unique lighting effect happens only on evenings with a clear sky. Minor haze or cloudiness can spoil the effect. Although entirely natural, the phenomenon is reminiscent of the human-caused Firefall that historically occurred from Glacier Point.

In popular culture

[edit]

The opening scenes of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) were filmed in Yosemite National Park. Films such as The Last of the Mohicans (1920) and Maverick (1994) have also been shot there.[149] The 2014 documentary Valley Uprising is centered around Yosemite Valley and its history with an emphasis on climbing culture.[150] The Academy Award-winning 2018 documentary Free Solo was filmed in Yosemite.[151] The Dawn Wall, a 2017 documentary, was filmed there.[152]

See also

[edit]- 1996 Yosemite Valley landslide

- Bibliography of the Sierra Nevada

- Buffalo Soldiers (park rangers)

- Cathedral Peak Granodiorite

- Chinquapin, California

- List of birds of Yosemite National Park

- List of national parks of the United States

- List of plants of the Sierra Nevada

- National parks in California

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Yosemite National Park

- Protected areas of the Sierra Nevada

- Yosemite Sam – Warner Bros. theatrical cartoon character

- Yosemite West, California, a community inside the gates of the park

- Yosemite Valley Railroad, a short-line railroad that replaced stagecoach travel to the park

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Yosemite National Park". protectedplanet.net. Protected Planet. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "Park Statistics". Yosemite National Park (U.S. National Park Service). Archived from the original on March 8, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Annual Park Ranking Report for Recreation Visits in: 2023". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "Yosemite Falls". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Harris 1998, p. 324

- ^ "Discover the High Sierra". California Office of Tourism. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Nature & History". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. October 13, 2006. Archived from the original on January 25, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Yosemite Wilderness". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ "Yosemite NP: Early History of Yosemite Valley". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Yosemite: Official National Park Service Handbook. no. 138. Washington, DC: National Park Service. 1989. p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Solnit, Rebecca (2014). Savage Dreams: a Journey into the Hidden Wars of the American West. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95792-3. OCLC 876343009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c "History & Culture". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Annual Park Recreation Visitation (1904 – Last Calendar Year)". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "New visitation record in 2016 as over 5 million people visited Yosemite National Park". GoldRushCam.com. Sierra Sun Times. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Top 10 most visited national parks". Travel. March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Dan. "Origin of the Word Yosemite". www.yosemite.ca.us. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ^ "Yosemite". Online etymology dictionary. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Barrett, S. A. (2010). Myths of the southern sierra miwok. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-177-40758-8. OCLC 944730381.

- ^ Beeler, Madison Scott (1955). "Yosemite and Tamalpais". Journal of the American Name Society. 3 (3): 185–86.

- ^ Runte, Alfred (1990). Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness. University of Nebraska Press. pp. Chapter 1. ISBN 0803238940.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spence, Mark (1996). "Dispossesing the Wilderness: Yosemite Indians and the National Park Ideal, 1864–1930". Pacific Historical Review. 65 (1): 27–59. doi:10.2307/3640826. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3640826.

- ^ Greene 1987, p. 78.

- ^ Starr, Kevin; Orsi, Richard J, eds. (2000). Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-520-22496-4.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (July 25, 2022). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 72–115. ISBN 978-1647920548. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Who We Are". Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "Sketch of Yosemite National Park and an Account of the Origin of the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valleys (History of Yosemite National Parkr)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Bingaman, John W. (1966). "The Ahwahneechees: A Story of the Yosemite Indians". yosemite.ca.us. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Godfrey, Elizabeth. "Yosemite Indians; Yesterday and Today". Yosemite Indians. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Bunnell, Lafayette H. (1892). "Chapter 17". Discovery of the Yosemite and the Indian War of 1851 Which Led to That Event. F.H. Revell. ISBN 0939666588. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ Bunnell, Lafayette H. Discovery of the Yosemite and the Indian War of 1851 Which Led to That Event.

- ^ Spence, Mark David (1999). "Yosemite Indians and the National Park Ideal, 1916-1969". Dispossessing the wilderness: Indian removal and the making of the national parks. pp. 115–132. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Indian Village of the Ahwahnee – Yosemite National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite Indians – Yosemite National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite Valley map" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Federal Recognition | Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation". SouthernSierra Miwuk. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Wolfley, Jeanette (2016). Reclaiming a presence in ancestral lands : the return of Native Peoples to the National Parks. [University of New Mexico, School of Law]. OCLC 1305864036. Archived from the original on February 5, 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Harris 1998, p. 326

- ^ Wuerthner 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Johns, J.S. (1996). "Discovery and Invention in the Yosemite". The Role of Railroads in Protecting, Promoting, and Selling Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Sargent, Shirley (1961). "Wawona's Yesterdays". Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Wawona Hotel Complex Cultural Landscape Report , Yosemite National Park. Mundus Bishop for National Park Service. August 2012. p. 15.

- ^ Schaffer, Jeffrey (June 2006). Yosemite National Park: A complete hiker's guide (5 ed.). Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press. p. 11. ISBN 0899973833. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Myth of the Tree You Can Drive Through". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ NPS 1989, p. 58.

- ^ Greene 1987, p. 360.

- ^ Radanovich, Leroy (2010). Yosemite Valley Railroad. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 9781439640333. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Greene 1987, pp. 362, 364.

- ^ Wuerthner 1994, p. 40.

- ^ Greene 1987, p. 387.

- ^ Gene Rose (March 2003). "The Ahwahnee: Yosemite Grandeur". Skiing Heritage Journal. International Skiing History Association: 21. ISSN 1082-2895.

- ^ Huth, Hans (March 1948). "Yosemite: The Story of an Idea". Sierra Club Bulletin (33). Sierra Club: 63–76. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ a b c Schaffer 1999, p. 48

- ^ Sanger, George P., ed. (1866). "Thirty-Eighth Congress, Session I, Chap. 184 (June 30, 1864): An Act authorizing a Grant to the State of California of the "Yo-Semite Valley" and of the Land embracing the "Mariposa Big Tree Grove"" (PDF). The Statutes At Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America from December 1863, to December 1865. Vol. 13. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 325. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Yosemite "State Park"". www.150.parks.ca.gov. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ Hutchings v. Low 82 U.S. 77 (1872)

- ^ Ashburner v. California 103 U.S. 575 (1880)

- ^ Runte, Alfred (1990). Yosemite : The Embattled Wilderness. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 34–35, 50. ISBN 0803289413.

- ^ a b Schaffer 1999, p. 49

- ^ Law Olmsted, Frederick (1865). Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove: A Preliminary Report. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "People – John Muir". The National Parks: America's Best Idea. PBS. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Olmsted, Frederick Law. "Olmsted Report on Management of Yosemite, 1865". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Schaffer 1999, p. 50

- ^ "Yosemite". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "John Muir and President Roosevelt". John Muir National Historic Site, California. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Schaffer 1999, p. 52

- ^ NPS 1989, p. 117.

- ^ George, Carmen. "American Indians share their Yosemite story". The Fresno Bee. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ Moseley, W. G. (2009). "Beyond Knee-Jerk Environmental Thinking: Teaching Geographic Perspectives on Conservation, Preservation and the Hetch Hetchy Valley Controversy". Journal of Geography in Higher Education. 33 (3): 433–51. doi:10.1080/03098260902982492. S2CID 143538071.

- ^ Schaffer 1999, p. 51

- ^ a b c "Women of Yosemite". National Park Service. 2022. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Furmansky, Dyana Z. (2009). Rosalie Edge, Hawk of Mercy: The Activist Who Saved Nature from the Conservationists. University of Georgia Press. pp. 200–07. ISBN 978-0820336763.

- ^ Dolan, Jack (January 30, 2025). "As Trump cuts federal jobs, even national parks are on the chopping block". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 1, 2025.

- ^ Pratt, Sara E (December 14, 2017). "Benchmarks: January 25, 1968: The last firefall: A Yosemite tradition flames out". Earth Magazine. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ "California Wilderness Act of 1984 - 98th U.S. Congress" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ National Park Service. "Ackerson Meadow Gifted to Yosemite National Park". Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (August 23, 2024). "Yosemite National Park: Crews restore damaged landscape back to conditions not seen in 150 years". The Mercury News. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "Nature & Science". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c Harris 1998, p. 329

- ^ "Geology: The Making of the Landscape". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Geological Survey Professional Paper 160: Geologic History of the Yosemite Valley – The Sierra Block". United States Geological Survey. November 28, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ Harris 1998, p. 331

- ^ a b Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 220

- ^ a b Harris 1998, p. 332

- ^ Cross, Robert (May 26, 1996). "Mountain majesty Yosemite: The California national park is home to some of the country's most scenic natural wonders". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park's Largest Glacier Stagnant – Yosemite National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Harris 1998, p. 340

- ^ a b Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 227

- ^ a b "Water Overview". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Hydrology and Watersheds". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Wetland Vegetation". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Tallest and Largest Waterfalls at the World Waterfall Database". www.worldwaterfalldatabase.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Krieger, Lisa (May 17, 2019). "Waterfalls are roaring this spring at Yosemite". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 228

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (October 1, 2013). "Yosemite's largest ice mass is melting fast". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite – Nature – Geology – Glaciers". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Liberatore (March 15, 2013). "Glaciers in Yosemite". Yosemite National Park trips. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Climate". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Yosemite Park Headquarters, CA (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park, California, USA – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Harris 1998, p. 328

- ^ Ernst, WG (2015). "Review of Late Jurassic-early Miocene sedimentationand plate-tectonic evolution of northern California: illuminatingexample of an accretionary margin" (PDF). Chin. J. Geochem. 34 (2): 123–42. Bibcode:2015Geoch..34..123E. doi:10.1007/s11631-015-0042-x. S2CID 55662231. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2020.

- ^ Schweickert, Richard A; Saleeby, Jason B; Tobisch, Othmar T; Wright, William H. III (1977). Paleotectonic and paleogeographic significance of the Calaveras Complex, western Sierra Nevada, California. Paleozoic paleogeography of the western United States : Pacific Coast Paleogeography Symposium I. Los Angeles, California: Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists. pp. 381–94. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 43–44. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2012/560. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 9, 2019.

- ^ Harris 1998, p. 337

- ^ Yonkee, W. Adolph; Weil, Arlo Brandon (November 1, 2015). "Tectonic evolution of the Sevier and Laramide belts within the North American Cordillera orogenic system". Earth-Science Reviews. 150: 531–93. Bibcode:2015ESRv..150..531Y. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.08.001. ISSN 0012-8252.

- ^ Hill, Mary (2006). Geology of the Sierra Nevada. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 270.

- ^ a b Harris 1998, p. 339

- ^ Konigsmark, Ted (2002). Geologic Trips, Sierra Nevada (PDF). GeoPress. p. 234. ISBN 0966131657. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Huber, N. King (1987). "Final Evolution of the Landscape". The Geologic Story of Yosemite National Park. Washington: Government Printing Office. USGS Bulletin 1595. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Volcanoes of the Eastern Sierra Nevada". sierra.sitehost.iu.edu. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Harris 1998, p. 333

- ^ Franklin, Jerry F.; Fites-Kaufmann, Jo Ann (1996). "21: Assessment of Late-Successional Forests of the Sierra Nevada" (PDF). Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project. Final Report to Congress. Status of the Sierra Nevada. Vol. II: Assessments and Scientific Basis for Management Options. Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California. pp. 627–71. ISBN 1887673016. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Bolsinger, Charles L.; Waddell, Karen L. (1993). "Area of old-growth forests in California, Oregon, and Washington" (PDF). Resource Bulletin (197). United States Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. PNW-RB-197. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from Wildlife Overview. National Park Service: Yosemite Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007.

This article incorporates public domain material from Wildlife Overview. National Park Service: Yosemite Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007.

- ^ "DNA to Help Identify "Problem" Bears at Yosemite". National Geographic. April 23, 2001. Archived from the original on April 30, 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ^ Graber, David M. (1996). "25: Status of Terrestrial Vertebrates". Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project. Final Report to Congress. Status of the Sierra Nevada Volume II: Assessments and Scientific Basis for Management Options (PDF). Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California. pp. 709–34. ISBN 1887673016. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Stephens, Tim. "Yosemite bears and human food: Study reveals changing diets over past century". UC Santa Cruz News. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Hughes, Trevor. "National park visitors leave roadkill in their wake". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Exotic Plants". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ^ "Giant Sequoias and Fire – Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Johnson, Eric Michael. "How John Muir's Brand of Conservation Led to the Decline of Yosemite". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Are There Good Forest Fires?". Evergreen Magazine. Summer 2002. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ "Yosemite Valley will close due to fire. 'Get yourself out of here,' official says". fresnobee. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Branch, John; Medina, Jennifer; Fountain, Henry (July 25, 2018). "Yosemite National Park Evacuated Amid Threat From Fire". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "Operating Hours & Seasons". Yosemite National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ "Yosemite in Winter". www.yosemitehikes.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ "Bus". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. May 27, 2009. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Aarian (May 24, 2019). "Hiking or Camping? Take the Bus to the Trail This Summer". Wired. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "Camp 4 Listed With National Register of Historic Places". NPS Press Release. National Park Service. February 27, 2003. Archived from the original on March 16, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ "Half Dome Day Hike". Yosemite National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ "Half Dome Permits for Day Hikers". Yosemite National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Cary, Russ. "Yosemite Hikes". Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ a b "Wilderness Permits". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. February 12, 2010. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Bear and food storage". National Park Service: National Park Service. February 10, 2010. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Auto Touring". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Biking". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. March 2007. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ "Climbing". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 11, 2008. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Camp 4 Listed With National Register of Historic Places" (Press release). National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. February 27, 2003. Archived from the original on March 16, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Skiing". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. September 21, 2006. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Tuolumne Meadows Winter Conditions Update". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Winter Wilderness Travel". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. March 2, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "History". The Bracebridge Dinner at Yosemite. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Yosemite camping". Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Plan Your Visit". Yosemite National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- ^ Brown, Ann Marie (2015). Moon Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon Hiking, Camping, Waterfalls & Big Trees. Avalon Publishing. Rafting. ISBN 9781640494459.

- ^ Maddrey, Joseph (2016). The Quick, the Dead and the Revived: The Many Lives of the Western Film. McFarland. p. 175. ISBN 978-1476625492.

- ^ Mortimer, Peter; Rosen, Nick; Lowell, Josh (September 1, 2014), Valley Uprising (Documentary), Peter Sarsgaard, Alex Honnold, Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, Sender Films, Big UP Productions, archived from the original on June 13, 2019, retrieved April 26, 2021

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (September 27, 2018). "Review: In 'Free Solo,' Braving El Capitan With Only Fingers and Toes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Lowell, Josh; Mortimer, Peter (July 17, 2018), The Dawn Wall (Documentary, Biography, Sport), John Branch, Tommy Caldwell, Kevin Jorgeson, Red Bull Media House, Sender Films, archived from the original on April 21, 2022, retrieved April 26, 2021

General references

[edit]- Berkowitz, Paul D. (2017). Legacy of the Yosemite Mafia: Noble Cause Corruption in the National Park Service. Walterville Oregon: Trine Day Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63424-126-7.

- Diamant, Rolf and Carr, Ethan (2022). Olmsted and Yosemite: Civil War, Abolition, and The National Park Idea. Amherst, Massachusetts: Library of American Landscape History ISBN 9781952620348 Online review of this book.

- Greene, Linda Wedel (1987). Yosemite: the Park and its Resources (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2011.

- Harris, Ann G. (1998). Geology of National Parks (Fifth ed.). Kendall, Iowa: Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0787253537.

- Kiver, Eugene P.; Harris, David V. (1999). Geology of U.S. Parklands (Fifth ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471332186.

- Muir, John. "Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park Archived September 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine" The Century; a popular quarterly (Sept. 1890) 40#5

- Schaffer, Jeffrey P. (1999). Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails. Berkeley: Wilderness Press. ISBN 0899972446.

- Wuerthner, George (1994). Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811725987.

- Yosemite: Official National Park Service Handbook. Vol. 138. Division of Publications, National Park Service. 1989.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

- "Climate". National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Exotic Vegetation". National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Nature & History". National Park Service. October 13, 2006. Archived from the original on January 25, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Water Overview". National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Wildlife Overview". National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the National Park Service

- "Providing for Yosemite's Future — Yosemite Conservancy". yosemite.org. March 18, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- "The Role of the Railroads in Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks". xroads.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on November 8, 1997. Retrieved June 28, 2023. from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Project Yosemite | Yosemite HD | Motion Timelapse Video

- "Historic Yosemite Indian Chiefs – with photos". Archived from the original on May 21, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- "Edith Irvine's Historic Photographs of Yosemite National Park". contentdm.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- Project Yosemite timelapse photography

- Muir, John (1911). My first summer in the Sierra. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.19229. "Audio recording". LibriVox.org. June 3, 2009.

- IUCN Category II

- Yosemite National Park

- World Heritage Sites in California

- 1890 establishments in California

- Protected areas established in 1890

- Sierra Nevada (United States)

- Parks in Madera County, California

- Parks in Mariposa County, California

- Parks in Tuolumne County, California

- World Heritage Sites in the United States

- Hetch Hetchy Project

- Protected areas of the Sierra Nevada (United States)

- National parks in California

- Nature centers in California

- Parks in Mono County, California