Brandenburg Concertos

| Brandenburg Concertos | |

|---|---|

| Concertos by J. S. Bach | |

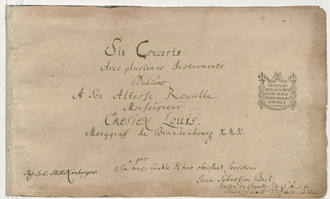

Title page, in French, of the six concertos | |

| Catalogue | BWV 1046–1051 |

| Form | Six concertos, each of several movements |

| Composed | Collection assembled in 1721 |

The Brandenburg Concertos (BWV 1046–1051) by Johann Sebastian Bach are a collection of six instrumental works presented by Bach to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, in 1721 (though probably composed earlier). The original French title is Six Concerts Avec plusieurs instruments, meaning "Six Concertos for several instruments". Some of the pieces feature several solo instruments in combination. They are widely regarded as some of the greatest orchestral compositions of the Baroque era.[1][2][3]

History

[edit]

It is uncertain when most of the material for the Brandenburg Concertos was written. It is clear that the first movement of Concerto No. 1 (BWV 1046) was based on an introduction to Bach's 1713 cantata Was mir behagt, and the second and last may have been as well.[4] It also seems likely that Concerto No. 5 was the last to be written; it features a prominent harpsichord part, which is presumed to be for a new instrument ordered for Prince Leopold from the instrument-maker Michael Mietke and paid for by Bach in Berlin in 1719.[5] Speculation regarding the composition dates of the other concertos varies, taking into account the styles of the pieces as well as the instrumentation Bach would have had available during his years prior to the date of the compiled manuscript.[6][7]

In 1721, Bach compiled the six concertos, writing them almost entirely in his own hand instead of leaving the work to a copyist.[8] He presented the collection to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, under the title Six Concerts Avec plusieurs instruments (Six Concertos for several instruments) with a dedication dated 24 March.[9] Translated from the original French, the first sentence of Bach's dedication reads:

As I had the good fortune a few years ago to be heard by Your Royal Highness, at Your Highness's commands, and as I noticed then that Your Highness took some pleasure in the little talents which Heaven has given me for Music, and as in taking Leave of Your Royal Highness, Your Highness deigned to honour me with the command to send Your Highness some pieces of my Composition: I have in accordance with Your Highness's most gracious orders taken the liberty of rendering my most humble duty to Your Royal Highness with the present Concertos, which I have adapted to several instruments; begging Your Highness most humbly not to judge their imperfection with the rigour of that discriminating and sensitive taste, which everyone knows Him to have for musical works, but rather to take into benign Consideration the profound respect and the most humble obedience which I thus attempt to show Him.[10]

It is likely that the performance this excerpt mentions happened during the trip Bach took to Berlin in 1719, to pay for the new Mietke harpsichord.[11]

Bach's titular reference to scoring the concertos for "several instruments" has drawn commentary. Christoph Wolff treats it as an understatement, observing that Bach used the "widest imaginable spectrum of orchestral instruments. The modest title does not begin to suggest the degree of innovation exhibited in the daring combinations ... Every one of the six concertos set a precedent in its scoring, and every one was to remain without parallel."[12] Boyd (1993) interprets it as an indication that the concertos are written in a Venetian style, "with its greater opportunities for soloistic display ... 'Concerti a quattro', 'Concerti a cinque' etc.",[13] and also perhaps that Bach was indicating the number of different instruments, or that the sound was intended to evoke a larger orchestra even with only one player to a part.[14] Heinrich Besseler has noted that the overall forces required (leaving aside the first concerto, which was rewritten for a special occasion) tallies exactly with the 17 players Bach had at his disposal in Köthen,[15] although Wolff contradicts this: "contrary to conventional wisdom, the collection does not reflect specific structure of ensembles available either to the margrave of Brandenburg or to the prince of Anhalt-Cöthen."[12]

In later years

[edit]It is often asserted that Christian Ludwig lacked the musicians in his Berlin ensemble to perform the concertos, and that the score was left unused in the Margrave's library until his death in 1734, but Boyd argues that the evidence does not necessarily support these assertions, and that "it seems unlikely that Bach would have sent him six concertos totally unsuitable for his musicians to play."[16] Nevertheless, the concertos were not included by name in the library inventory after Christian Ludwig's death, and it is uncertain who they went to. The next owner we have a record of was Bach's own pupil Johann Kirnberger, who left the collection to Princess Anna Amalia on his death, who subsequently bequeathed it to the Joachimsthal Gymnasium from which it was transferred to the Royal Library of Berlin (now the Berlin State Library) in 1914.[17] The manuscript was nearly lost during World War II, while being transported for safekeeping to Prussia by train in the care of a librarian – the train came under aerial bombardment, and the librarian escaped from the train to a nearby forest, with the scores hidden under his coat.[18] As of 2023[update] the manuscript remains in the Berlin State Library.[3]

After Bach's death only the fifth concerto received any widespread attention, probably due to the fashion for keyboard concertos; the rest seem to have been forgotten. The pieces were rediscovered by Siegfried Dehn, who found them in Princess Amalia's library in 1849 and had them published for the first time the following year, the centenary of Bach's death.[19] However, this publication appears not to have spurred large numbers of performances, and those that did occur tended to adapt the instrumentation to the forces available to modern orchestras. The concertos' current place in the canon is instead owed to the advent of recording technology; the first recording of the complete set was made in 1936, directed by Adolf Busch, and the revival of interest in historically informed performance made the pieces popular for further recordings on period instruments.[20] They have also been performed as chamber music, with one instrument per part, especially by groups using "baroque instruments" and historically informed techniques and practice. There is also an arrangement for four-hand piano duet by composer Max Reger.

A Karl Richter recording of Concerto No. 2 was sent into space in 1977 on the Voyager Golden Record.[21]

In 2001, the piece came in at number 22 in the Classic 100 Original (ABC) listing. In 2007, all six of the concertos appeared on the Classic 100 Concerto (ABC) listing.

Concertos

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

In the overview table, the first column shows the title, the second the key, the third the number in the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV), the fourth the prominent instruments (solo).

| Concerto | Key | BWV | Solo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 | F major | 1046 |

|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 | F major | 1047 |

|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 | G major | 1048 |

|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 | G major | 1049 |

|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 | D major | 1050 |

|

| Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 | B-flat major | 1051 |

|

Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 1mo à 2 Corni di Caccia, 3 Hautb: è Bassono, Violino Piccolo concertato, 2 Violini, una Viola è Violoncello, col Basso Continuo.[22]

- [no tempo indication] (usually performed at Allegro or Allegro moderato)

- Adagio in D minor

- Allegro

- Menuet – Trio I – Menuet da capo – Polacca – Menuet da capo – Trio II – Menuet da capo

Instrumentation: two corni da caccia (natural horns), three oboes, bassoon, violino piccolo, two violins, viola and basso continuo (harpsichord, cello, viola da gamba and/or violone)

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 1, BWV 1046.2 (BWV 1046),[23] is the only one in the collection with four movements. The concerto also exists in an alternative version, Sinfonia BWV 1046.1 (formerly BWV 1046a),[24] which appears to have been composed during Bach's years at Weimar. The Sinfonia, which lacks the third movement entirely, and the Polacca (or Poloinesse, polonaise) from the final movement, appears to have been intended as the opening of the cantata Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd, BWV 208. This implies a date of composition possibly as early as the 1713 premiere of the cantata, although it could have been used for a subsequent revival.[25]

The first movement can also be found as the sinfonia of a later cantata Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht, BWV 52, but in a version without the piccolo violin that is closer to Sinfonia BWV 1046a. The third movement was used as the opening chorus of the cantata Vereinigte Zwietracht der wechselnden Saiten, BWV 207, where the horns are replaced by trumpets.

Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino, concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo.[22]

- [no tempo indication] (usually performed at Allegro)

- Andante in D minor

- Allegro assai

Concertino: natural trumpet in F, recorder, oboe, violin

Ripieno: two violins, viola, violone, cello and harpsichord (as basso continuo)

The trumpet part is still considered one of the most difficult in the entire repertoire, and was originally written for a clarino specialist, almost certainly the court trumpeter in Köthen, Johann Ludwig Schreiber.[26] After clarino skills were lost in the eighteenth century and before the rise of the historically informed performance movement of the late twentieth century, the part was often played on the piccolo trumpet in B♭, and occasionally on a French horn.[citation needed]

The clarino does not play in the second movement, as is common practice in baroque era concerti. This is due to its construction, which allows it to play only in major keys. Because concerti often move to a minor key in the second movement, concerti that include the instrument in their first movement and are from the period before the valved trumpet was commonly used usually exclude the trumpet from the second movement.

The first movement of this concerto was chosen as the first musical piece to be played on the Voyager Golden Record, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of Earth's common sounds, languages, and music sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes. The first movement served as a theme for Great Performances in the early-to-mid 1980s, while the third movement served as the theme for William F. Buckley Jr.'s Firing Line; a revival featuring Margaret Hoover also used the first movement.

Recent research has revealed that this concerto is based on a lost chamber music version for quintet called "Concerto da camera in Fa Maggiore" (Chamber Concerto in F major), whose catalogue number is BWV 1047R. It is similar to the orchestral version, in that the trumpet, flute, oboe and solo violin parts are the same, but the orchestra part has been arranged for basso continuo (or piano) by Klaus Hofmann. This reconstructed quintet arrangement is also the very first piano reduction of the 2nd Brandenburg Concerto ever published by Bärenreiter Verlag (Product Number BA 5196).

Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 3zo à tre Violini, tre Viole, è tre Violoncelli col Basso per il Cembalo.[22]

- [no tempo indication] (usually performed at Allegro or Allegro moderato)

- Adagio in E minor

- Allegro

Instrumentation: three violins, three violas, three cellos, and harpsichord (as basso continuo)

The second movement consists of a single measure with the two chords that make up a 'Phrygian half cadence'[27] and although there is no direct evidence to support it, it is likely that these chords were meant to surround or follow a cadenza improvised by the harpsichord or a solo violin player. Modern performance approaches range from simply playing the cadence with minimal ornamentation (treating it as a sort of "musical semicolon"), to cadenzas varying in length from under a minute to over two minutes. Occasionally, other slow movements from Bach pieces, such as the Largo from the Sonata for Violin and Continuo in G, BWV 1021 and the Largo from the Sonata for Violin and Obbligato Harpsichord in G major, BWV 1019, are substituted for the second movement as they contain an identical 'Phrygian cadence' as the closing chords.

The outer movements use the ritornello form found in many instrumental and vocal works of the time. The first movement can also be found in reworked form as the sinfonia of the cantata Ich liebe den Höchsten von ganzem Gemüte, BWV 174, with the addition of three oboes and two horns.

This concerto is the shortest of the six.

Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 4to à Violino Principale, due Fiauti d'Echo, due Violini, una Viola è Violone in Ripieno, Violoncello è Continuo.[22]

- Allegro

- Andante in E minor

- Presto

Concertino: violin and two recorders (described in the original score as "flauti d'echo").

Ripieno: two violins, violas, violone, cellos and basso continuo (harpsichord and/or viola da gamba)

The violin part in this concerto is extremely virtuosic in the first and third movements. In the second movement, the violin provides a bass when the concertino group plays unaccompanied.

It has been debated what instrument Bach had in mind for the "fiauti d'echo" parts. Nowadays these are usually played on alto recorders,[28] although transverse flutes are sometimes used instead: it is also theorised Bach's original intent may have been the flageolet. In some performances, such as those conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, the two recorders are positioned offstage, thus giving an "echo" effect.

Bach adapted the 4th Brandenburg concerto as a harpsichord concerto, BWV 1057.

Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 5to à une Traversiere, une Violino principale, une Violino è una Viola in ripieno, Violoncello, Violone è Cembalo concertato.[22]

- Allegro

- Affettuoso in B minor

- Allegro

Concertino: harpsichord, violin, flute

Ripieno: violin, viola, cello and violone

The harpsichord is both a concertino and a ripieno instrument. In the concertino passages the part is obbligato; in the ripieno passages it has a figured bass part and plays continuo.

This concerto makes use of a popular chamber music ensemble of the time (flute, violin, and harpsichord), which Bach used on its own for the middle movement. It is believed[by whom?] that it was written in 1719, to show off a new harpsichord by Michael Mietke which Bach had brought back from Berlin for the Köthen court. It is also thought that Bach wrote it for a competition at Dresden with the French composer and organist Louis Marchand; in the central movement, Bach uses one of Marchand's themes. Marchand fled before the competition could take place, apparently scared off in the face of Bach's great reputation for virtuosity and improvisation.

The concerto is well suited throughout to showing off the qualities of a fine harpsichord and the virtuosity of its player, but especially in the lengthy solo cadenza to the first movement. It seems almost certain that Bach, considered a great organ and harpsichord virtuoso, was the harpsichord soloist at the premiere. Scholars have seen in this work the origins of the solo keyboard concerto as it is the first example of a concerto with a solo keyboard part.[29][30]

An earlier version, BWV 1050a, exists, and has many small differences from its later cousin, but no major difference in structure or instrumentation. It is dated ca. 1720–21.

Concerto No. 6 in B-flat major, BWV 1051

[edit]Title on autograph score: Concerto 6to a due Viole da Braccio, due Viole da Gamba, Violoncello, Violone e Cembalo.[22]

- [no tempo indication, alla breve] (usually performed at Allegro or Allegro moderato)

- Adagio ma non tanto (in E♭ major, ends in an imperfect cadence of G minor)

- Allegro

Instrumentation: two viole da braccio, two viole da gamba, cello, violone, and harpsichord

The absence of violins is unusual, but it is also found in a cantata written at Wiemar Gleichwie der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt, BWV 18. Viola da braccio means the normal viola, and is used here to distinguish it from the viola da gamba. The viola da gamba was already an old-fashioned instrument when Bach compiled the Brandenburg Concertos in 1721: one reason for using it may have been the interest which his employer, Prince Leopold, had in the instrument. Nikolaus Harnoncourt speculated that Prince Leopold wished to play with his orchestra and that Bach's provision of such music was somehow related to the fact that he was looking for jobs elsewhere. By upsetting the balance of the musical roles, he would be released from his servitude as Kapellmeister.[31]

The two violas start the first movement with a vigorous subject in close canon, and as the movement progresses, the other instruments are gradually drawn into the seemingly uninterrupted steady flow of melodic invention which shows the composer's mastery of polyphony. The two violas da gamba are silent in the second movement, leaving the texture of a trio sonata for two violas and continuo, although the cello has a decorated version of the continuo bass line. In the last movement, the spirit of the gigue underlies everything, as it did in the finale of the fifth concerto.

References

[edit]- ^ "Milestones of the Millennium: Bach's "Brandenburg" Concertos". NPR. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Bach – Brandenburg Concertos". Classic FM. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b Stewart 2023.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 10, 15.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 38, 100.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 9–11, 24.

- ^ "Bach – Brandenburg Concerto No. 3". Classical Music for Pleasure. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Boyd 1993, p. 10.

- ^ a b Wolff 2000, p. 232.

- ^ Boyd 1993, p. 24.

- ^ Boyd 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Besseler's preface to the Neue Bach-Ausgabe edition of the Brandenburg Concertos is reprinted with a translation in Bärenreiter's Study Score of the Six Brandenburg Concertos (Bärenreiter TP9, 1988)

- ^ Boyd 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Boyd 1993, p. 18.

- ^ Siblin, Eric (2010). The Cello Suites: In Search of a Baroque Masterpiece. Random House. p. 266. ISBN 978-1409089100.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Boyd 1993, pp. 21–22.

- ^ "Golden Record: Music From Earth". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Johann Sebastian Bach's Werke, vol. 19: Kammermusik, dritter band, Bach-Gesellschaft, Leipzig; ed. Wilhelm Rust, 1871

- ^ "Brandenburg Concerto no. 1, F (revised version) BWV 1046.2; BWV 1046". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sinfonia, F (Brandenburg Concerto no. 1, early version) BWV 1046.1; BWV 1046a; formerly BWV 1071". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 15 April 2020.

- ^ Marissen, Michael (1992). "On linking Bach's F-major Sinfonia and his Hunt Cantata". Bach. 23 (2): 31–46. JSTOR 41634120.

- ^ Utnes, Ole J. "J. S. Bach and the 2nd Brandenburg Concerto". Abel.hive.no. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ wikt:Phrygian cadence

- ^ The range of both recorder parts in the 4th Brandenburg concerto corresponds to that of the alto recorder

- ^ Steinberg, M. The Concerto: A Listener's Guide, p. 14, Oxford (1998) ISBN 0-19-513931-3

- ^ Hutchings, A. 1997. A Companion to Mozart's Piano Concertos, p. 26, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816708-3

- ^ This explanation is given by Nikolaus Harnoncourt in his interview about the sixth concerto, which features in the 2009 Deutsche Grammophon DVD Johann Sebastian Bach: Brandenburg Concertos.

Further reading

[edit]- Boyd, Malcolm (1993). Bach: The Brandenburg Concertos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521382769. OL 1734852M.

- Marissen, Michael (1999). The Social and Religious Designs of J. S. Bach's Brandenburg Concertos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00686-5.

- Stewart, Andrew (24 March 2023). "Bach's Groundbreaking 'Brandenburg Concertos': Masterpiece Guide". uDiscover Music. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- Wolff, Christoph (2000). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. OL 7451664M.

External links

[edit]Scores

- Brandenburg Concertos: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

Essays

- classicalnotes.net: Brandenburg Concertos – Comprehensive discussion by Peter Gutmann including assessment of recordings

- Inkpot: The Brandenburg Concertos – An introduction by Benjamin Chee

- good-music-guide.com: Brandenburg Concertos – Introductory survey

Recordings

- List of recordings, with reviews, from jsbach.org

- Brandenburg Concerto No. 1, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2, Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, Brandenburg Concerto No. 4, Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 and Brandenburg Concerto No. 6: performances by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

- High-Definition video of Brandenburg Concertos 3 & 4 performed on original instruments by the ensemble Voices of Music, copyright free for use in classrooms

- 1721 compositions

- Compositions in F major

- Compositions in G major

- Compositions in D major

- Compositions in B-flat major

- Compositions for trumpet

- Compositions for viola

- Compositions for horn

- Compositions for bassoon

- Compositions for cello

- Compositions for flute

- Compositions for oboe

- Concerti grossi

- Concertos by Johann Sebastian Bach

- Harpsichord concertos

- Violin concertos

- Köthen (Anhalt)

- Contents of the Voyager Golden Record

- Concertos for multiple instruments