Book: Difference between revisions

LedgendGamer (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 116.50.171.90 (talk) to last version by Suffusion of Yellow |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

{{main|History of the book}} |

{{main|History of the book}} |

||

=== Antiquity === |

=== Antiquity === |

||

KIER BADING |

|||

[[Image:Sumerian MS2272 2400BC.jpg|thumb|[[Sumerian language]] cuneiform script [[clay tablet]], 2400–2200 BC]] |

|||

When [[History of writing|writing systems]] were invented in [[ancient civilization]]s, nearly everything that could be written upon—stone, [[clay tablet|clay]], tree bark, metal sheets—was used for writing. [[History of the alphabet|Alphabetic writing]] emerged in [[Egypt]] around 1800 BC. The Ancient Egyptians would often times write on [[papyrus]], a plant grown along the Nile River. At first the words were not separated from each other (''scriptura continua'') and there was no [[punctuation]]. Texts were written from right to left, left to right, and even so that alternate lines read in opposite directions. The technical term for this type of writing is '[[boustrophedon]],' which means literally 'ox-turning' for the way a farmer drives an ox to plough his fields. |

|||

==== Scroll ==== |

==== Scroll ==== |

||

kier AMPATUAN JR. |

|||

{{main|Scroll}} |

|||

[[Image:Egypt.Papyrus.01.jpg|thumb|left|Egyptian papyrus showing the god [[Osiris]] and the weighing of the heart.]] |

|||

[[Papyrus]], a thick [[paper|paper-like]] material made by weaving the stems of the papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool, was used for writing in [[Ancient Egypt]], perhaps as early as the [[First Dynasty]], although the first evidence is from the account books of King [[Neferirkare Kakai]] of the [[Fifth Dynasty]] (about 2400 BC).<ref>{{Cite book |

|||

| publisher = American Library Association; The British Library |

|||

| isbn = 9780838905227 |

|||

| last = Avrin |

|||

| first = Leila |

|||

| title = Scribes, script, and books: the book arts from antiquity to the Renaissance |

|||

| location = New York, New York |

|||

| date = 1991 |

|||

| pages = 83 |

|||

}}</ref> Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a [[Scroll (parchment)|scroll]]. Tree bark such as [[Tilia|lime]] (Latin ''liber'', from there also [[library]]) and other materials were also used.<ref>[[Dard Hunter]]. ''Papermaking: History and Technique of an Ancient Craft New ed.'' Dover Publications 1978, p. 12.</ref> |

|||

According to [[Herodotus]] (History 5:58), the [[Phoenicians]] brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the tenth or ninth century BC. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (''biblion'') and book (''biblos'') come from the Phoenician port town [[Byblos]], through which papyrus was exported to Greece.<ref>Leila Avrin. ''Scribes, Script and Books'', pp. 144–145.</ref> From Greeks we have also the word tome ({{lang-el|τόμος}}) which originally meant a slice or piece and from there it became to denote "a roll of papyrus". ''Tomus'' was used by the Latins with exactly the same meaning as ''volumen'' (see also below the explanation by Isidore of Seville). |

|||

Whether made from papyrus, [[parchment]], or paper in East Asia, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese and Hebrew cultures. The more modern [[codex]] book format form took over the Roman world by [[late antiquity]], but the scroll format persisted much longer in Asia. |

|||

==== Codex ==== |

|||

{{main|Codex}} |

|||

[[Image:Herkulaneischer Meister 002b.jpg|thumb|upright|Woman holding a book (or wax tablets) in the form of the [[codex]]. Wall painting from [[Pompeii]], before 79 AD.]] |

|||

[[Papyrus]] scrolls were still dominant in the first century AD, as witnessed by the findings in [[Pompeii]]. The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from [[Martial]], in his Apophoreta <small>CLXXXIV</small> at the end of the century, where he praises its compactness. However the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.<ref>The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Edd. Frances Young, Lewis Ayres, Andrew Louth, Ron White. Cambridge University Press 2004, pp. 8–9.</ref> This change happened gradually during the third and fourth centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan texts written on scrolls. |

|||

[[Image:Bamboo book - binding - UCR.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A Chinese [[bamboo]] book]] |

[[Image:Bamboo book - binding - UCR.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A Chinese [[bamboo]] book]] |

||

[[Wax tablet]]s were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman ''pugillares'') is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex).<ref>Leila Avrin. ''Scribes, Script and Books'', p. 173.</ref> The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.<ref>{{Cite book |

[[Wax tablet]]s were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman ''pugillares'') is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex).<ref>Leila Avrin. ''Scribes, Script and Books'', p. 173.</ref> The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.<ref>{{Cite book |

||

Revision as of 03:57, 20 January 2010

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

A book is a set or collection of written, printed, illustrated, or blank sheets, made of paper, parchment, or other various material, usually fastened together to hinge at one side. A single sheet within a book is called a leaf, and each side of a leaf is called a page. A book produced in electronic format is known as an electronic book (e-book).

Books may also refer to a literature work, or a main division of such a work. In library and information science, a book is called a monograph, to distinguish it from serial periodicals such as magazines, journals or newspapers. The body of all written works including books is literature.

In novels, a book may be divided into several large sections, also called books (Book 1, Book 2, Book 3, etc).

A lover of books is usually referred to as a bibliophile, a bibliophilist, or a philobiblist, or, more informally, a bookworm.

A store where books are bought and sold is a bookstore or bookshop. Books can also be borrowed from libraries.

Etymology

The word book comes from Old English "bōc" which comes from Germanic root "*bōk-", cognate to beech.[1] Similarly, in Slavic languages (e.g. Russian and Bulgarian "буква" (bukva)—"letter") is cognate to "beech". It is thus conjectured that the earliest Indo-European writings may have been carved on beech wood.[2] Similarly, the Latin word codex, meaning a book in the modern sense (bound and with separate leaves), originally meant "block of wood."

History of books

Antiquity

KIER BADING

Scroll

kier AMPATUAN JR.

Wax tablets were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex).[3] The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[4]

In the 5th century, Isidore of Seville explained the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): "A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches."

Middle Ages

Manuscripts

The fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Papyrus became difficult to obtain due to lack of contact with Egypt, and parchment, which had been used for centuries, became the main writing material.

Monasteries carried on the Latin writing tradition in the Western Roman Empire. Cassiodorus, in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540), stressed the importance of copying texts.[5] St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Regula Monachorum (completed around the middle of the 6th century) later also promoted reading.[6] The Rule of St. Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. The tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated, but slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged.

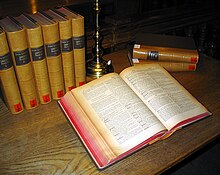

Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, which made books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only a few dozen books, medium-sized perhaps a few hundred. By the ninth century, larger collections held around 500 volumes and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.[7]

The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house. Artificial light was forbidden for fear it may damage the manuscripts. There were five types of scribes:

- Calligraphers, who dealt in fine book production

- Copyists, who dealt with basic production and correspondence

- Correctors, who collated and compared a finished book with the manuscript from which it had been produced

- Illuminators, who painted illustrations

- Rubricators, who painted in the red letters

The bookmaking process was long and laborious. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by the scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally, the book was bound by the bookbinder.[8]

Different types of ink were known in antiquity, usually prepared from soot and gum, and later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing a brownish black color, but black or brown were not the only colors used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and different colors were used for illumination. Sometimes the whole parchment was colored purple, and the text was written on it with gold or silver (for example, Codex Argenteus).[9]

Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the seventh century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However, the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before the 12th century. It has been argued that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading.[10]

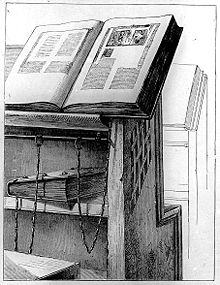

The first books used parchment or vellum (calf skin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. Because dried parchment tends to assume the form it had before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During the later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, up to 18th century, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. These chained books are called libri catenati.

At first, books were copied mostly in bars, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the 13th century, the Manuscript culture of the time led to an increase in the demand for books, and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by secular stationers guilds, which produced both religious and non-religious material.[11]

Judaism has kept the art of the scribe alive up to the present. According to Jewish tradition, the Torah scroll placed in a synagogue must be written by hand on parchment, and a printed book would not do, though the congregation may use printed prayer books, and printed copies of the Scriptures are used for study outside the synagogue. A sofer (scribe) is a highly respected member of any observant Jewish community.

Paper books

The Arabs revolutionised the book's production and its binding in the medieval Islamic world. They were the first to produce paper books after they learnt paper industry from the Chinese in the 8th century.[12] Particular skills were developed for script writing (Arabic calligraphy), miniatures and bookbinding. The people who worked in making books were called Warraqin or paper professionals. The Arabs made books lighter—sewn with silk and bound with leather covered paste boards, they had a flap that wrapped the book up when not in use. As paper was less reactive to humidity, the heavy boards were not needed. The production of books became a real industry and cities like Marrakech, Morocco, had a street named Kutubiyyin or book sellers which contained more than 100 bookshops in the 12th century; the famous Koutoubia Mosque is named so because of its location in this street. In the words of Don Baker:

The world of Islam has produced some of the most beautiful books ever created. The need to write down the Revelations which the Prophet Muhammad, may peace be upon him, received, fostered the desire to beautify the object which conveyed these words and initiated this ancient craft. Nowhere else, except perhaps in China, has writing been held in such high esteem. Splendid illumination was added with gold and vibrant colours, and the whole book contained and protected by beautiful bookbindings.[13]

Wood block printing

In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. This method originated in China, in the Han dynasty (before 220AD), as a method of printing on textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 AD).

The method (called Woodcut when used in art) arrived in China in the early 14th century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page; and the wood blocks tended to crack, if stored for long. The monks or people who wrote them were paid highly.

Movable type and incunabula

The Chinese inventor Pi Sheng made movable type of earthenware circa 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Metal movable type was invented in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (around 1230), but was not widely used: one reason being the enormous Chinese character set. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce, and more widely available.

Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before the year 1501 in Europe are known as incunabula. A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.[14]

Modern world

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 1800s. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour, but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.

Monotype and linotype presses were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once.

The centuries after the 15th century were thus spent on improving both the printing press and the conditions for freedom of the press through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-20th century, Europe book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

Book manufacturing in the modern world

The methods used for the printing and binding of books continued fundamentally unchanged from the 15th century into the early years of the 20th century. While there was of course more mechanization, Gutenberg would have had no difficulty in understanding what was going on if he had visited a book printer in 1900.

Gutenberg’s “invention” was the use of movable metal types, assembled into words, lines, and pages and then printed by letterpress. In letterpress printing ink is spread onto the tops of raised metal type, and is transferred onto a sheet of paper which is pressed against the type. Sheet-fed letterpress printing is still available but tends to be used for collector’s books and is now more of an art form than a commercial technique (see Letterpress).

Today, the majority of books are printed by offset lithography in which an image of the material to be printed is photographically or digitally transferred to a flexible metal plate where it is developed to exploit the antipathy between grease (the ink) and water. When the plate is mounted on the press, water is spread over it. The developed areas of the plate repel water thus allowing the ink to adhere to only those parts of the plate which are to print. The ink is then offset onto a rubbery blanket (to avoid all that water soaking the paper) and then finally to the paper (see Lithography).

When a book is printed the pages are laid out on the plate so that after the printed sheet is folded the pages will be in the correct sequence. [see Imposition] Books tend to be manufactured nowadays in a few standard sizes. The sizes of books are usually specified as “trim size”: the size of the page after the sheet has been folded and trimmed. Trimming involves cutting approximately 1/8” off top, bottom and fore-edge (the edge opposite to the spine) as part of the binding process in order to remove the folds so that the pages can be opened. The standard sizes result from sheet sizes (therefore machine sizes) which became popular 200 or 300 years ago, and have come to dominate the industry. The basic standard commercial book sizes in America, always expressed as width x height in USA; some examples are: 4-1/4” x 7” (rack size paperback) 5-1/8” x 7-5/8” (digest size paperback) 5-1/2” x 8-1/4” 5-1/2” x 8-1/2” 6-1/8” x 9-1/4” 7” x 10” 8-1/2” x 11”. These “standard” trim sizes will often vary slightly depending on the particular printing presses used, and on the imprecision of the trimming operation. Of course other trim sizes are available, and some publishers favor sizes not listed here which they might nominate as “standard” as well, such as 6” x 9”, 8” x 10”. In Britain the equivalent standard sizes differ slightly, as well as now being expressed in millimeters, and with height preceding width. Thus the UK equivalent of 6-1/8” x 9-1/4” is 234 x 156 mm. British conventions in this regard prevail throughout the English speaking world, except for USA. The European book manufacturing industry works to a completely different set of standards.

Some books, particularly those with shorter runs (i.e. of which fewer copies are to be made) will be printed on sheet-fed offset presses, but most books are now printed on web presses, which are fed by a continuous roll of paper, and can consequently print more copies in a shorter time. On a sheet-fed press a stack of sheets of paper stands at one end of the press, and each sheet passes through the press individually. The paper will be printed on both sides and delivered, flat, as a stack of paper at the other end of the press. These sheets then have to be folded on another machine which uses bars, rollers and cutters to fold the sheet up into one or more signatures. A signature is a section of a book, usually of 32 pages, but sometimes 16, 48 or even 64 pages. After the signatures are all folded they are gathered: placed in sequence in bins over a circulating belt onto which one signature from each bin is dropped. Thus as the line circulates a complete “book” is collected together in one stack, next to another, and another.

A web press carries out the folding itself, delivering bundles of signatures ready to go into the gathering line. Notice that when the book is being printed it is being printed one (or two) signatures at a time, not one complete book at a time. Thus if there are to be 10,000 copies printed, the press will run 10,000 of the first form (the pages imaged onto the first plate and its back-up plate, representing one or two signatures), then 10,000 of the next form, and so on till all the signatures have been printed. Actually, because there is a known average spoilage rate in each of the steps in the book’s progress through the manufacturing system, if 10,000 books are to be made, the printer will print between 10,500 and 11,000 copies so that subsequent spoilage will still allow the delivery of the ordered quantity of books. Sources of spoilage tend to be mainly make-readies.

A make-ready is the preparatory work carried out by the pressmen to get the printing press up to the required quality of impression. Included in make-ready is the time taken to mount the plate onto the machine, clean up any mess from the previous job, and get the press up to speed. The main part of making-ready is however getting the ink/water balance right, and ensuring that the inking is even across the whole width of the paper. This is done by running paper through the press and printing waste pages while adjusting the press to improve quality. Desitometers are used to ensure even inking and consistency from one form to another. As soon as the pressman decides that the printing is correct, all the make-ready sheets will be discarded, and the press will start making books. Similar make readies take place in the folding and binding areas, each involving spoilage of paper.

After the signatures are folded and gathered, they move into the bindery. In the middle of the last century there were still many trade binders – stand-alone binding companies which did no printing, specializing in binding alone. At that time, largely because of the dominance of letterpress printing, the pattern of the industry was for typesetting and printing to take place in one location, and binding in a different factory. When type was all metal, a typical book’s worth of type would be bulky, fragile and heavy. The less it was moved in this condition the better: so it was almost invariable that printing would be carried out in the same location as the typesetting. Printed sheets on the other hand could easily be moved. Now, because of the increasing computerization of the process of preparing a book for the printer, the typesetting part of the job has flowed upstream, where it is done either by separately contracting companies working for the publisher, by the publishers themselves, or even by the authors. Mergers in the book manufacturing industry mean that it is now unusual to find a bindery which is not also involved in book printing (and vice versa).

If the book is a hardback its path through the bindery will involve more points of activity than if it is a paperback. A paperback binding line (a number of pieces of machinery linked by conveyor belts) involves few steps. The gathered signatures, book blocks, will be fed into the line where they will one by one be gripped by plates converging from each side of the book, turned spine up and advanced towards a gluing station. En route the spine of the book block will be ground off leaving a roughened edge to the tightly gripped collection of pages. The grinding leaves fibers which will grip onto the glue which is then spread onto the spine of the book. Covers then meet up with the book blocks, and one cover is dropped onto the glued spine of each book block, and is pressed against the spine by rollers. The book is then carried forward to the trimming station, where a three-knife trimmer will simultaneously cut the top and bottom and the fore-edge of the paperback to leave clear square edges. The books are then packed into cartons, or packed on skids, and shipped.

Binding a hardback is more complicated. Look at a hardback book and you will see the cover overlaps the pages by about 1/8” all round. These overlaps are called squares. The blank piece of paper inside the cover is called the endpaper, or endsheet: it is of somewhat stronger paper than the rest of the book as it is the endpapers that hold the book into the case. The endpapers will be tipped to the first and last signatures before the separate signatures are placed into the bins on the gathering line. Tipping involves spreading some glue along the spine edge of the folded endpaper and pressing the endpaper against the signature. The gathered signatures are then glued along the spine, and the book block is trimmed, like the paperback, but will continue after this to the rounder and backer. The book block together with its endpapers will be gripped from the sides and passed under a roller with presses it from side to side, smashing the spine down and out around the sides so that the entire book takes on a rounded cross section: convex on the spine, concave at the fore-edge, with “ears” projecting on either side of the spine. Then the spine is glued again, a paper liner is stuck to it and headbands and footbands are applied. Next a crash lining (an open weave cloth somewhat like a stronger cheesecloth) is usually applied, overlapping the sides of the spine by an inch or more. Finally the inside of the case, which has been constructed and foil-stamped off-line on a separate machine, is glued on either side (but not on the spine area) and placed over the book block. This entire sandwich is now gripped from the outside and pressed together to form a solid bond between the endpapers and the inside of the case. The crash lining, which is glued to the spine of the pages, but not the spine of the case, is held between the endpapers and the case sides, and in fact provides most of the strength holding the book block into the case. The book will then be jacketed (most often by hand, allowing this stage to be an inspection stage also) before being packed ready for shipment.

The sequence of events can vary slightly, and usually the entire sequence does not occur in one continuous pass through a binding line. What has been described above is unsewn binding, now increasingly common. The signatures of a book can also be held together by Smyth sewing. Needles pass through the spine fold of each signature in succession, from the outside to the center of the fold, sewing the pages of the signature together and each signature to its neighbors. McCain sewing, often used in schoolbook binding, involves drilling holes through the entire book and sewing through all the pages from front to back near the spine edge. Both of these methods mean that the folds in the spine of the book will not be ground off in the binding line. This is true of another technique, notch binding, where gashes about an inch long are made at intervals through the fold in the spine of each signature, parallel to the spine direction. In the binding line glue is forced into these “notches” right to the center of the signature, so that every pair of pages in the signature is bonded to every other one, just as in the Smyth sewn book. The rest of the binding process is similar in all instances. Sewn and notch bound books can be bound as either hardbacks or paperbacks.

Making cases happens off-line and prior to the book’s arrival at the binding line. In the most basic case making, two pieces of cardboard are placed onto a glued piece of cloth with a space between them into which is glued a thinner board cut to the width of the spine of the book. The overlapping edges of the cloth (about 5/8” all round) are folded over the boards, and pressed down to adhere. After case making the stack of cases will go to the foil stamping area. Metal dies, photoengraved elsewhere, are mounted in the stamping machine and rolls of foil are positioned to pass between the dies and the case to be stamped. Heat and pressure cause the foil to detach from its backing and adhere to the case. Foils come in various shades of gold and silver and in a variety pigment colors, and by careful setup quite elaborate effects can be achieved by using different rolls of foil on the one book. Cases can also be made from paper which has been printed separately and then protected with clear film lamination. A three-piece case is made similarly but has a different material on the spine and overlapping onto the sides: so it starts out as three pieces of material, one each of a cheaper material for the sides and the different, stronger material for the spine.

Recent developments in book manufacturing include the development of digital printing. Book pages are printed, in much the same way as an office copier works, using toner rather than ink. Each book is printed in one pass, not as separate signatures. Digital printing has permitted the manufacture of much smaller quantities than offset, in part because of the absence of make readies and of spoilage. One might think of a web press as printing quantities over 2000, quantities from 250 to 2000 being printed on sheet-fed presses, and digital presses doing quantities below 250. These numbers are of course only approximate and will vary from supplier to supplier, and from book to book depending on its characteristics. Digital printing has opened up the possibility of print-on-demand, where no books are printed until after an order is received from a customer.

Transition to digital format

The term e-book is a contraction of "electronic book"; it refers to a digital version of a conventional print book. An e-book is usually made available through the internet, but also on CD-ROM and other forms. E-Books may be read either via a computer or by means of a portable book display device known as an e-book reader, such as the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble Nook or the Amazon Kindle. These devices attempt to mimic the experience of reading a print book.

Throughout the 20th century, libraries have faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the Internet means that much new information is not printed in paper books, but is made available online through a digital library, on CD-ROM, or in the form of e-books. An on-line book is an e-book that is available online through the internet.

Though many books are produced digitally, most digital versions are not available to the public, and there is no decline in the rate of paper publishing [citation needed]. There is an effort, however, to convert books that are in the public domain into a digital medium for unlimited redistribution and infinite availability. This effort is spearheaded by Project Gutenberg combined with Distributed Proofreaders.

There have also been new developments in the process of publishing books. Technologies such as print on demand, which make it possible to print as few as one million books at a time, have made self-publishing much easier and more affordable. On-demand publishing has allowed publishers, by avoiding the high costs of warehousing, to keep low-selling books in print rather than declaring them out of print.

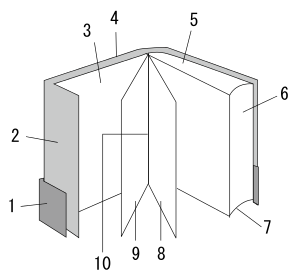

Book structure

- Belly band

- Flap

- Endpaper

- Book cover

- Top edge

- Fore edge

- Tail edge

- Right page, recto

- Left page, verso

- Gutter

The common structural parts of a book include:

- Front cover: hardbound or softcover (paperback); the spine is the binding that joins the front and rear covers where the pages hinge.

- Front endpaper

- Flyleaf: The blank leaf or leaves following the front free endpaper.

- Front matter

- Frontispiece

- Title page

- Copyright page: typically verso of title page: shows copyright owner/date, credits, edition/printing, cataloguing details

- Table of contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Body: the text or contents, the pages often collected or folded into signatures; the pages are usually numbered sequentially, and often divided into chapters.

- Back matter

- Flyleaf: The blank leaf or leaves (if any) preceding the back free endpaper.

- Rear endpaper

- Rear cover

A thin marker, commonly made of paper or card, used to keep one's place in a book is a bookmark. Bookmarks were used throughout the medieval period,[15] consisting usually of a small parchment strip attached to the edge of folio (or a piece of cord attached to headband). Bookmarks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were narrow silk ribbons bound into the book and become widespread in the 1850s. They were usually made from silk, embroidered fabrics or leather. Not until the 1880s did paper and other materials become more common.

The process of physically assembling a book from a number of folded or unfolded sheets of paper is bookbinding.

Sizes

The size of a modern book is based on the printing area of a common flatbed press. The pages of type were arranged and clamped in a frame, so that when printed on a sheet of paper the full size of the press, the pages would be right side up and in order when the sheet was folded, and the folded edges trimmed.

The most common book sizes are:

- Quarto (4to): the sheet of paper is folded twice, forming four leaves (eight pages) approximately 11-13 inches (ca 30 cm) tall

- Octavo (8vo): the most common size for current hardcover books. The sheet is folded three times into eight leaves (16 pages) up to 9 ¾" (ca 23 cm) tall.

- DuoDecimo (12mo): a size between 8vo and 16mo, up to 7 ¾" (ca 18 cm) tall

- Sextodecimo (16mo): the sheet is folded four times, forming sixteen leaves (32 pages) up to 6 ¾" (ca 15 cm) tall

Sizes smaller than 16mo are:

- 24mo: up to 5 ¾" (ca 13 cm) tall.

- 32mo: up to 5" (ca 12 cm) tall.

- 48mo: up to 4" (ca 10 cm) tall.

- 64mo: up to 3" (ca 8 cm) tall.

Small books can be called booklets.

Sizes larger than quarto are:

- Folio: up to 15" (ca 38 cm) tall.

- Elephant Folio: up to 23" (ca 58 cm) tall.

- Atlas Folio: up to 25" (ca 63 cm) tall.

- Double Elephant Folio: up to 50" (ca 127 cm) tall.

The largest extant medieval manuscript in the world is Codex Gigas 92 × 50 × 22 cm. The world's largest book made of stone is in Kuthodaw Pagoda (Myanmar).

Types of books

Types of books according to their contents

A common separation by content are fiction and non-fictional books. By no means are books limited to this classification, but it is a separation that can be found in most collections, libraries, and bookstores.

Fiction

Many of the books published today are fictitious stories. They are in-part or completely untrue or fantasy. Historically, paper production was considered too expensive to be used for entertainment. An increase in global literacy and print technology led to the increased publication of books for the purpose of entertainment, and allegorical social commentary. Most fiction is additionally categorized by genre.

The novel is the most common form of fictional book. Novels are stories that typically feature a plot, setting, themes and characters. Stories and narrative are not restricted to any topic; a novel can be whimsical, serious or controversial. The novel has had a tremendous impact on entertainment and publishing markets.[16]

Comic books or graphic novels are books in which the story is not told, but illustrated.

Non-fiction

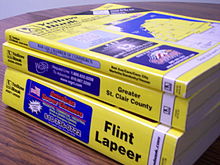

In a library, a reference book is a general type of non-fiction book which provides information as opposed to telling a story, essay, commentary, or otherwise supporting a point of view. An almanac is a very general reference book, usually one-volume, with lists of data and information on many topics. An encyclopedia is a book or set of books designed to have more in-depth articles on many topics. A book listing words, their etymology, meanings, and other information is called a dictionary. A book which is a collection of maps is an atlas. A more specific reference book with tables or lists of data and information about a certain topic, often intended for professional use, is often called a handbook. Books which try to list references and abstracts in a certain broad area may be called an index, such as Engineering Index, or abstracts such as chemical abstracts and biological abstracts.

Books with technical information on how to do something or how to use some equipment are called instruction manuals. Other popular how-to books include cookbooks and home improvement books.

Students typically store and carry textbooks and schoolbooks for study purposes. Elementary school pupils often use workbooks, which are published with spaces or blanks to be filled by them for study or homework. In US higher education, it is common for a student to take an exam using a blue book.

There is a large set of books that are made only to write private ideas, notes, and accounts. These books are rarely published and are typically destroyed or remain private. Notebooks are blank papers to be written in by the user. Students and writers commonly use them for taking notes. Scientists and other researchers use lab notebooks to record their spork. They often feature spiral coil bindings at the edge so that pages may easily be torn out.

Address books, phone books, and calendar/appointment books are commonly used on a daily basis for recording appointments, meetings and personal contact information.

Books for recording periodic entries by the user, such as daily information about a journey, are called logbooks or simply logs. A similar book for writing the owner's daily private personal events, information, and ideas is called a diary or personal journal.

Businesses use accounting books such as journals and ledgers to record financial data in a practice called bookkeeping.

Other types

There are several other types of books which are not commonly found under this system. Albums are books for holding a group of items belonging to a particular theme, such as a set of photographs, card collections, and memorabilia. One common example is stamp albums, which are used by many hobbyists to protect and organize their collections of postage stamps. Such albums are often made using removable plastic pages held inside in a ringed binder or other similar smolder.

Hymnals are books with collections of musical hymns that can typically be found in churches. Prayerbooks or missals are books that contain written prayers and are commonly carried by monks, nuns, and other devoted followers or clergy.

Types of books according to their binding or cover

Hardcover books have a stiff binding. Paperback books have cheaper, flexible covers which tend to be less durable. An alternative to paperback is the glossy cover, otherwise known as a dust cover, found on magazines, and comic books. Spiral-bound books are bound by spirals made of metal or plastic. Examples of spiral-bound books include: teachers' manuals and puzzle books (crosswords, sudoku).

Publishing is a process for producing pre-printed books, magazines, and newspapers for the reader/user to buy.

Publishers may produce low-cost, pre-publication copies known as galleys or 'bound proofs' for promotional purposes, such as generating reviews in advance of publication. Galleys are usually made as cheaply as possible, since they are not intended for sale.

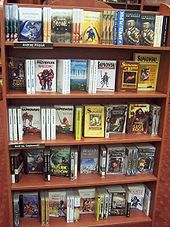

Collections of books

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books, (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. In ancient world the maintaining of a library was usually (but not exclusively) the privilege of a wealthy individual. These libraries could have been either private or public, i.e. for people who were interested in using them. The difference from a modern public library lies in the fact that they were usually not funded from public sources. It is estimated that in the city of Rome at the end of the third century there were around 30 public libraries. Public libraries also existed in other cities of the ancient Mediterranean region (e.g. Library of Alexandria).[17] Later, in the Middle Ages, monasteries and universities had also libraries that could be accessible to general public. Typically not the whole collection was available to public, the books could not be borrowed and often were chained to reading stands to prevent theft.

The beginning of modern public library begins around 15th century when individuals started to donate books to towns.[18] The growth of a public library system in the United States started in the late 19th century and was much helped by donations from Andrew Carnegie. This reflected classes in a society: The poor or the middle class had to access most books through a public library or by other means while the rich could afford to have a private library built in their homes.

The advent of paperback books in the 20th century led to an explosion of popular publishing. Paperback books made owning books affordable for many people. Paperback books often included works from genres that had previously been published mostly in pulp magazines. As a result of the low cost of such books and the spread of bookstores filled with them (in addition to the creation of a smaller market of extremely cheap used paperbacks) owning a private library ceased to be a status symbol for the rich.

In library and booksellers' catalogues, it is common to include an abbreviation such as "Crown 8vo" to indicate the paper size from which the book is made.

When rows of books are lined on a book holder, bookends are sometimes needed to keep them from slanting.

Identification and classification

During the 20th century, librarians were concerned about keeping track of the many books being added yearly to the Gutenberg Galaxy. Through a global society called the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), they devised a series of tools including the International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD).

Each book is specified by an International Standard Book Number, or ISBN, which is unique to every edition of every book produced by participating publishers, world wide. It is managed by the ISBN Society. An ISBN has four parts: the first part is the country code, the second the publisher code, and the third the title code. The last part is a check digit, and can take values from 0–9 and X (10). The EAN Barcodes numbers for books are derived from the ISBN by prefixing 978, for Bookland, and calculating a new check digit.

Commercial publishers in industrialized countries generally assign ISBNs to their books, so buyers may presume that the ISBN is part of a total international system, with no exceptions. However many government publishers, in industrial as well as developing countries, do not participate fully in the ISBN system, and publish books which do not have ISBNs.

A large or public collection requires a catalogue. Codes called "call numbers" relate the books to the catalogue, and determine their locations on the shelves. Call numbers are based on a Library classification system. The call number is placed on the spine of the book, normally a short distance before the bottom, and inside.

Institutional or national standards, such as ANSI/NISO Z39.41 - 1997, establish the correct way to place information (such as the title, or the name of the author) on book spines, and on "shelvable" book-like objects, such as containers for DVDs, video tapes and software.

One of the earliest and most widely known systems of cataloguing books is the Dewey Decimal System. This system has fallen out of use in some places, mainly because of a Eurocentric bias and other difficulties applying the system to modern libraries. However, it is still used by most public libraries in America. The Library of Congress Classification system is more popular in university libraries. [citation needed]

Information about books and authors can be stored in databases like online general-interest book databases.

Metadata about a book may include its ISBN or other classification number (see above), the names of contributors (author, editor, illustrator) and publisher, its date and size, and the language of the text.

Classification systems

- Bliss bibliographic classification (BC)

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Colon Classification

- Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)

- Harvard-Yenching Classification

- Library of Congress Classification (LCC)

- New Classification Scheme for Chinese Libraries

- Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

Uses for books

Aside from the primary purpose of reading them, books are also used for other ends:

- A book can be an artistic artifact; this is sometimes known as an artists' book.

- A book may be evaluated by a reader or professional writer to create a book review.

- A book may be read by a group of people to use as a spark for social or academic discussion, as in a book club.

- A book may be studied by students as the subject of a writing and analysis exercise in the form of a book report.

- Books are sometimes used for their exterior appearance to decorate a room, such as a study.

Paper and conservation issues

Though papermaking in Europe had begun around the 11th century, up until the beginning of 16th century vellum and paper were produced congruent to one another, vellum being the more expensive and durable option. Printers or publishers would often issue the same publication on both materials, to cater to more than one market.

Paper was first made in China, as early as 200 B.C., and reached Europe through Muslim territories. At first made of rags, the industrial revolution changed paper-making practices, allowing for paper to be made out of wood pulp.

Paper made from wood pulp was introduced in the early-20th century, because it was cheaper than linen or abaca cloth-based papers. Pulp-based paper made books less expensive to the general public. This paved the way for huge leaps in the rate of literacy in industrialised nations, and enabled the spread of information during the Second Industrial Revolution.

However pulp paper contained acid, that eventually destroys the paper from within. Earlier techniques for making paper used limestone rollers, which neutralized the acid in the pulp. Books printed between 1850 and 1950 are at risk; more recent books are often printed on acid-free or alkaline paper. Libraries today have to consider mass deacidification of their older collections.

Stability of the climate is critical to the long-term preservation of paper and book material.[19] Good air circulation is important to keep fluctuation in climate stable. The HVAC system should be up to date and functioning efficiently. Light is detrimental to collections. Therefore, care should be given to the collections by implementing light control. General housekeeping issues can be addressed, including pest control. In addition to these helpful solutions, a library must also make an effort to be prepared if a disaster occurs, one that they cannot control. Time and effort should be given to create a concise and effective disaster plan to counteract any damage incurred through “acts of god” therefore a emergency management plan should be in place.

The proper care of books takes into account the possibility of physical and chemical damage to the cover and text. Books are best stored out of direct sunlight, in reduced lighting, at cool temperatures, and at moderate humidity. They need the support of surrounding volumes to maintain their shape, so it is desirable to shelve them by size.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ book - Definitions from Dictionary.com

- ^ Northvegr - Holy Language Lexicon

- ^ Leila Avrin. Scribes, Script and Books, p. 173.

- ^ Bischoff, Bernhard (1990). Latin palaeography antiquity and the Middle Ages. Translated by Dáibhí ó Cróinin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0521364736.

- ^ Leila Avrin. Scribes, Script and Books, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Theodore Maynard. Saint Benedict and His Monks. Staples Press Ltd 1956, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Martin D. Joachim. Historical Aspects of Cataloguing and Classification. Haworth Press 2003, p. 452.

- ^ Edith Diehl. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. Dover Publications 1980, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Paul Saenger. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press 1997.

- ^ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Al-Hassani, Woodcock and Saoud, "1001 Inventions, Muslim heritage in Our World", FSTC Publishing, 2006, reprinted 2007, pp.218-219.

- ^ Baker, Don, "The golden age of Islamic bookbinding", Ahlan Wasahlan, (Public Relations Div., Saudi Arabian Airlines, Jeddah), 1984. pp. 13-15 [13]

- ^ Clapham, Michael, "Printing" in A History of Technology, Vol 2. From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, edd. Charles Singer et al. (Oxford 1957), p. 377. Cited from Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge University, 1980).

- ^ For a 9th century Carolingian bookmark see: Szirmai, J. A. (1999). The archaeology of medieval bookbinding. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 123. ISBN 0859679047. For a 15th century bookmark see Medeltidshandskrift 34, Lund University Library.

- ^ Edwin Mcdowell (1989-10-30). "The Media Business; Publishers Worry After Fiction Sales Weaken". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science (Marcel Dekker, 2003), "Public Libraries, History".

- ^ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library, "Public Libraries, History".

- ^ Patkus, Beth (2003), Assessing Preservation Needs, A Self-Survey Guide, Andover: Northeast Document Conservation Center