Bletchley

| Bletchley | |

|---|---|

Queensway, the main shopping street in Bletchley. | |

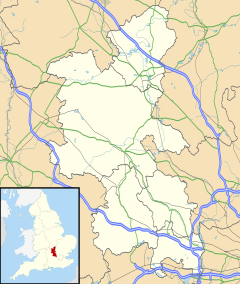

Mapping © OpenStreetMap Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 37,114 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP872336 |

| • London | 43 miles (69 km) |

| Civil parish | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MILTON KEYNES |

| Postcode district | MK1-3 |

| Dialling code | 01908 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament |

|

Bletchley is a constituent town of Milton Keynes,[2][3] Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated in the south-west of the city, and is split between the civil parishes of Bletchley and Fenny Stratford and West Bletchley. In 2011, the two parishes had a combined population of 37,114.

Bletchley is best known for Bletchley Park, the headquarters of Britain's World War II codebreaking organisation, and now a major tourist attraction. The National Museum of Computing is also located on the Park.

History

[edit]Origins and early modern history

[edit]The town name is Anglo-Saxon and means Blæcca's clearing.[4][5] It was first recorded in manorial rolls in the 12th century as Bicchelai, then later as Blechelegh (13th century) and Blecheley (14th–16th centuries).[6] Just to the south of Fenny Stratford, there was Romano-British town, MAGIOVINIUM on either side of Watling Street, a Roman road.

Bletchley was originally a minor village on the outskirts of Fenny Stratford, of lesser importance than Water Eaton.[6] Fenny Stratford fell into decline from the English Civil War (17c) onwards.[6] The arrival of the London and Birmingham Railway (now part of the West Coast Main Line) from 1838, and particularly of the branch lines to Bedford (1846) and Buckingham (1850) (that together subsequently became the Oxford – Cambridge "Varsity Line"), made the station at Bletchley a substantial one. Bletchley grew to eclipse both its antecedents.[6]

Almost forty years after the construction of Bletchley railway station, the 1884/5 Ordnance Survey shows Bletchley as still just a small village around the C of E parish church at Old Bletchley, and a (separate) hamlet near the Methodist chapel and Shoulder of Mutton public house at the junction of Shenley Road/Newton Road with Buckingham Road.[7] (These districts are known today as Old Bletchley and Far Bletchley). The major settlement of the time is nearby Fenny Stratford.

The Bletchley area is rich in Oxford Clay, which has long been used for bricks. Brick-making has taken place on the Newton Leys site and the surrounding area from the late 19th century, circa 1897.[8] Bletchley Brickworks closed in September 1990.[9]

"Bigger, Better, Brighter" – Bletchley in the 20th century

[edit]In the urban growth of the Victorian period brought by the railway, the town merged with Fenny Stratford. The latter had been constituted an urban district (with Simpson) in 1895, and Bletchley was added in 1898. By 1911, the population of the combined parishes was 5,166 but the balance between them had changed: in that year, the name of the local council (Urban District) changed from Fenny Stratford UD to Bletchley UD.[10] The 1926 Ordnance Survey shows the settlements beginning to merge, with large private houses along the Bletchley Road between them. In 1933, the newly founded Bletchley Gazette began a campaign for a "Bigger, Better, Brighter, Bletchley".[11] As the nation emerged from World War II, Bletchley Council renewed its desire to expand from its 1951 population of 10,919. By mid-1952, the council was able to agree terms with five London Boroughs to accept people and businesses from bombed-out sites in London.[12] This trend continued through the 1950s and 1960s, culminating[a] in the GLC-funded Lakes Estate in Water Eaton parish, even as Milton Keynes was being founded. Industrial development kept pace, with former London businesses relocating to new industrial estates in Mount Farm and Denbigh – Marshall Amplification being the most notable. With compulsory purchase, Bletchley Road (now renamed to Queensway after a royal visit in 1966) became the new high street with wide pavements where front gardens once lay. Houses near the railway end were replaced by shops but those nearer Fenny Stratford became banks and professional premises. At the 1971 Census, the population of the Bletchley Urban District was 30,642.[14]

Bletchley in Milton Keynes

[edit]Proposals for a new city in North Buckinghamshire had been floated from the early 1960s. Bletchley had fought to be the centre of the proposed new city, but it was not to be. When the Milton Keynes designation order was made in 1967, Bletchley was at its southern end rather than its centre. The 1971 Plan for Milton Keynes placed Central Milton Keynes on a completely new hill-top site four miles further north, halfway to Wolverton. Bletchley was relegated to the status of suburb.[15] Bletchley thrived in the early years of the growth of Milton Keynes, since it was the main shopping area. Bletchley centre was altered considerably when the Brunel Shopping Centre was built in the early 1970s, creating a new end to Queensway. (Previously, Queensway – formerly known as Bletchley Road – was a continuous run from Fenny Stratford to Old Bletchley). Bletchley's boom came to an end when the new Central Milton Keynes Shopping Centre was built and commercial Bletchley has declined as a retail destination since then.

The town's importance as a major hub within Milton Keynes and the wider region was recognised in March 2021 following a successful bid by the Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Town Deal Board, when MK City Council was successful in securing an award of £22.7mn as part of the UK Government's "New Towns Deal",[16] with the City Council focusing most of that money on Bletchley and Fenny Stratford. This led to the publishing of the Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Town Investment Plan (TIP),[17] with the plan aiming to boost jobs, skills and connectivity in the area, and further invest in Central Bletchley (the town centre).[18]

Bletchley Park

[edit]

Within the West Bletchley parish, in the Church Green district, is Bletchley Park, which, during the Second World War, was home to the Government Code and Cypher School. The German Enigma code was cracked here by, amongst others, Alan Turing. Another cipher machine was solved with the aid of early computing devices, known as Colossus. The park is now a museum, although many areas of the park grounds have been sold off for housing development.

Wilton Hall

[edit]The nearby Wilton Hall was built in 1943 as part of the Bletchley Park estate and was used by the government as a meeting place by day and a music and dance venue by night. After World War II, the venue continued to remain open and played host to musicians such as Lulu and The Rolling Stones.

In recent years, the building was slated for demolition after its closure in 2019. However, after residents and the local MP rejected calls for the demolition of the site due to historical value, the building was sold to a new partnership in 2020 who have refurbished and reopened the building in 2022.

Civil parishes: Bletchley and Fenny Stratford, and West Bletchley

[edit]For more details about the districts of Bletchley, see these civil parish articles.

The Bletchley built-up area is divided for administrative purposes into two civil parishes, Bletchley and Fenny Stratford and West Bletchley

The districts that make up Bletchley and Fenny Stratford CP are: Brickfields (includes the Blue Lagoon), Central Bletchley, Denbigh (including Denbigh North), Eaton Manor, Fenny Stratford, Granby, Manor Farm, Mount Farm, Newton Leys and Water Eaton (includes "Lakes Estate"). At the 2011 Census, the population of the parish was 15,313.[19]

West Bletchley CP covers that part of Milton Keynes that is south of Standing Way (A421), west of the West Coast Main Line and north of the Varsity Line. At the 2011 Census, the population of the parish was 15,313.[20] The districts and neighbourhoods in the parish are: Church Green (including Bletchley Park); Far Bletchley; Old Bletchley; West Bletchley (district); Whaddon (ward around Whaddon Way, not to be confused with nearby Whaddon in Aylesbury Vale).

In 1961 the parish of Bletchley had a population of 17,095.[21] On 1 April 1974 the parish was abolished and became an unparished area of the Milton Keynes district.[22]

Transport

[edit]Rail

[edit]The town is served by Bletchley railway station, on Sherwood Drive, which is on both the West Coast Main Line and the Bletchley-Bedford Marston Vale Line, a constituent part of the former Oxford-Cambridge Varsity Line that closed in 1967. However, a major project called East West Rail is underway to rebuild and reopen the route to the west of Bletchley to Bicester Village via Winslow;[23] the line from Bicester Village to Oxford has already been rebuilt. Eventually, full services through to Cambridge are planned.[24]

Road

[edit]Major Milton Keynes grid roads serving the town include Watling Street (which has the V4 designation between Denbigh North and Stony Stratford), V7 Saxon Street (connecting Central Bletchley with the rest of the city) and H8 Standing Way (A421) (which runs westwards towards Buckingham, the M40 and Oxford, and eastwards through the south-east of the city crossing and connecting to the M1 at Junction 13 and running towards Bedford, the A1 and Cambridge). The A5 passes along the eastern flank of Fenny Stratford, connecting it and Bletchley with the city centre, the A509, A422 and A508 roads. The A4146 southern bypass serves Water Eaton, Newton Leys and Fenny Stratford.

Watling Street, originally the Roman road between Dover and Wroxeter and serving Magiovinium (the Romano-British town that preceded Fenny, runs through Fenny Stratford and on through Stony Stratford).

Bus

[edit]Bletchley is MK's main southern interchange point for cross-city and rural bus services. The town is served by Arriva buses 4, 5, 6, 150, F70/F77 and M6; Z&S Transport bus 50; Red Rose bus 100; and Star Travel bus 162.[25]

The town's main bus station is located on South Terrace, just east of V7 Saxon Street in Central Bletchley.

MK City Council also operates an on demand bus service known as "MK Connect", which serves the whole MK unitary authority area, including Bletchley.[26]

Sport and leisure

[edit]Bletchley has a football club, Milton Keynes Irish and a rugby union club, Bletchley RUFC, both of which play at Manor Fields just south of Fenny Stratford.

Bletchley Leisure Centre was completed in 2009, replacing the original 1970s building.

Stadium MK, home of Milton Keynes Dons is at the northern edge of the town. This area also contains what is known as the "MK1" shopping centre. This includes shops, restaurants, and an Odeon cinema (which moved to MK1 from The Point building in Milton Keynes Central in 2015).

Political representation

[edit]Bletchley is divided between three electoral wards of Milton Keynes City Council, consisting of Bletchley East (3 Labour), Bletchley West (2 Labour, 1 Conservative) and Bletchley Park (1 Labour, 2 Conservative),[27] and is in the parliamentary constituency of Milton Keynes South.[citation needed]

ONS built up area

[edit]For the 2011 census, the Office for National Statistics designated a "built up area sub-division", being that part of Milton Keynes that is west of the A5 and south of the A421, some 1,073.5 hectares (2,652.7 acres).[1] At the 2011 census, the population of the area was 37,114.[1]

For the 2001 census, it designated a (larger) "urban sub-area" that approximates to the boundaries of the former Bletchley Urban District Council at the time of the designation of Milton Keynes. It also included that part of Winslow Rural District that fell within the designation. In outline, the ONS Sub-area consisted of Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Civil Parish, West Bletchley Civil Parish and part of Shenley Brook End Civil Parish (specifically Furzton, Emerson Valley, Tattenhoe and Snelshall).[28] At the 2001 Census, the population of the Sub-area was 47,176.[29]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ meaning both "the last" and "the best". The Greater London Council (GLC) was very proud of the Lakes Estate, declaring it to be the finest in modern architecture for a working class estate, based on the design concept pioneered in Radburn, New Jersey[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Bletchley (E35000902)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Official map of Milton Keynes showing original designated area boundary

- ^ (unknown) (6 February 1969). "Plannning study | Milton Keynes: new city for south-east". The Architects' Journal.

- ^ Bennitt, F.W (1933). Bletchley. H. Jackson.

- ^ "Key to English place names: Bletchley". Institute for Name-Studies, the University of Nottingham. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Parishes : Bletchley with Fenny Stratford and Water Eaton". A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 4. Victoria History of the Counties of England. 1927. p. 274–283. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Ordnance Survey (1885). "Buckinghamshire XV (includes: Bletchley; Bow Brickhill; Walton.)" (Map). OS Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952. 1:10,560. Ordnance Survey – via National Library of Scotland.

- ^ "Living Archive – Bletchley Bricks". Living Archive. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Newton Leys Strategic Flood Risk Assessment and Surface Water Drainage Strategy" (PDF). Peter Brett Associates. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ^ "Vision of Britain: Bletchley and Fenny Stratford". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Hill, Marion (ed.). Bigger Brighter Better. Milton Keynes: Living Archive. ISBN 0-904847-29-2.

- ^ "Bletchley: Early Days of Overspill". Clutch Club. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Bendixson, Terence; Platt, John (1992). Milton Keynes: Image and reality. Cambridge: Granta Editions. ISBN 978-0906782729.

- ^ "Vision of Britain: Bletchley Urban District". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies; Weeks; Forestier-Walker; Bor (1970). The Plan for Milton Keynes, Volume 1. Wavendon: Milton Keynes Development Corporation. ISBN 0-903379-00-7.

- ^ "Investment in Bletchley and Fenny Stratford". Milton Keynes City Council. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Town Investment Plan" (PDF). Milton Keynes City Council. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Single town in Milton Keynes to be 'transformed' with £23m funding, Chancellor's budget confirms today". Milton Keynes Citizen. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Bletchley and Fenny Stratford (E04012176)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – West Bletchley (E04012194)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Population statistics Bletchley AP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "North Bucks Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ EWR Alliance (April 2020). "EWR2 Project Newsletter, Spring 2020". Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Front Page". East West Rail Consortium. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Bus and Taxi, Bus Timetables, Maps and Travel Updates". Milton Keynes City Council.

- ^ "On-Demand Rideshare in Milton Keynes powered by Via". Via.

- ^ "CMIS > Councillors". milton-keynes.cmis.uk.com. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Map of Bletchley USa

- ^ KS01 Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas, line 1809

Further reading

[edit]- Edward Legg, Early History of Bletchley Park 1235–1937, Bletchley Park Trust Historic Guides series, No. 1, 1999