Black Death in the Holy Roman Empire

The Black Death was present in the Holy Roman Empire between 1348 and 1351.[1] The Holy Roman Empire, composed of modern-day Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands, was, geographically, the largest country in Europe at the time, and the pandemic lasted several years due to the size of the Empire.

Several witness accounts do exist from the Black Death in the Holy Roman Empire, although they were often either written after the events took place, or are very short.[1]

Background

[edit]The Holy Roman Empire in the mid-14th century

[edit]

At this point in time, the Holy Roman Empire was the geographically largest nation in Europe, though the population of France was bigger. It was a personal union under the King of Bohemia, who was also the Holy Roman Emperor.[2]

The Black Death

[edit]Since the outbreak of the Black Death at the Crimea, it had reached Sicily by an Italian ship from the Crimea. After having spread across the Italian states, and from Italy to France, the plague reached the borders of the Empire from France in the West, and from Italy in the South.[3]

Progress of the plague

[edit]The bubonic plague pandemic known as the Black Death reached Switzerland and Austria from Northern Italy in the South and Savoy in the West, and the Rhine and Central Germany from Northern France, and Northern Germany from Denmark. It continued from the Empire East to the Baltics and finally to the Rus' principalities.[4]

Switzerland

[edit]The Black Death reached Switzerland south from Ticino in Italy, and West to Rhone and Geneva from Avignon in France. According to tradition, Mühldorf am Inn was the first German language city to be affected by the Black Death, on 29 June 1348.[1] Most of Switzerland was affected during the year of 1349, when the plague reached Bern, Zürich, Basel and Saint Gallen.[5]

Austria

[edit]The Black Death in Austria is mainly described by the chronicle of the Neuberg Monastery in Steiermark. The Neuberg Chronicle dates the outbreak of plague in Austria to the feast of St Martin on 11 November 1348. In parallel with the plague, severe floods affected Austria. The plague interrupted the ongoing feud among the nobility, who were forced to cooperate against it. The Neuberg Chronicle describes an outbreak of festivities among the peasantry and public to distract themselves from the catastrophe, and how law and order collapsed.[1] The plague reached Vienna in May 1349, where it lasted until September and killed about one-third of the population.[6]

Germany

[edit]Southern Germany

[edit]In the summer of 1349, the plague spread from Basel in Switzerland North toward Strasbourg. The plague reached Strasbourg from Colmar 8 July.[7]

During the summer and autumn of 1349, the plague spread West from Strasbourg toward Mainz, Kassel, Limburg, Kreuznach, Sponheim and finally (in December) to Cologne; and East toward Augsburg, Ulm, Essingen and Stuttgart.[1]

Northern Germany

[edit]The Black Death reached Northern Germany in the early summer of 1350 when it arrived in Magdeburg, Halberstadt, Lübeck and Hamburg. The plague appears to have reached the Northern port cities in different time periods, likely because it was spread by sea rather than land: the inland cities of Northern Germany, significantly, were affected at a later date in 1350 than the port cities along the North coast.[1]

It finally reached Prussia and from there to the Baltics in 1351, and from there to the Rus' principalities.[8]

Low Countries

[edit]The Black Death events in the present-day Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg are documented in a range of sources.[9] In the often brief descriptions that feature in sources that have survived, three common elements can be identified:

- reports of a severe plague that caused lots of people to die everywhere (commonly referred to as "(the) great dying"[b]), although no clear cause was found, and only some people appeared to have figured out that measures such as social distancing could prevent or slow infections;[9]

- groups of itinerant Christian flagellants (gheesselaren, geselaars, g(h)eselbroeders "flagellant brothers"), also named "Cross Brothers" (Cruysbroeders, cruus broeders), who publicly whipped their own bodies in penance, hoping to appease the apparent wrath of God whom they believed had unleashed this plague upon them as punishment for their sins;[9] and

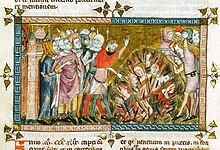

- groups of Christians accusing Jews of having conspired to poison the water wells (which supposedly caused the deaths), and persecuting them by burning them at the stake in public executions, usually organised by the local authorities.[9]

The Lower Rhine city of Cologne appears to have experienced an outbreak of Black Death as early as 1347, for which the local Cronica vander hiliger stat Coellen (1499) records: "In the said year [1347] and the two years after, there was a great dying throughout the world, both amongst the pagans and the Christians."[9] Two pages later, brief reports are given on the "Flagellant Brothers" (Geysellbroederen) or "Cross Bearers" (Cruysdreger), and the burning of the Jews,[c] without linking these three events (the same juxtaposition without connection happens in the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel).[9] On the other hand, a chronicle on the Duchy of Guelders, written in Nijmegen around 1459, does link all three events:

Int Jair ons heren mo ccco xlix / Doe gyngen dieCruysbroeders / Ende men slouch die Joeden doitwanttet was groitte starfte

("In the Year of our Lord 1349, the Cross Brothers went around; and people beat to death the Jews, because there was great dying."[9])

In June 1349, abbot Gilles Li Muisis from Saint-Martin Abbey, Tournai reported large numbers of deaths, and mass graves being dug to bury the deceased.[9] Furthermore, he noted that people were accusing the Jews of allegedly having poisoned the water wells which had supposedly caused the epidemic; as a result, many Jews were persecuted and burnt at the stake, with massacres taking places in Brussels and Cologne.[9] Muisis wrote these events down without judgement as to whether he believed the accusations, nor how he thought about the way the authorities handled the persecutions, as if he did not know what to do with the situation.[9] On the other hand, Muisis showed great sympathy for the Christian piety displayed by the itinerant groups of flagellants.[9]

The last chapter of Book V of the Brabantsche Yeesten, a rhymed chronicle by Antwerp clerk Jan van Boendale (died c. 1351), was entitled On the Flagellants (Van den gheesselaren[10]).[9]

| In des hertoghen Jans tiden Soe moest die heilighe kerke liden Ende doeghen swaerlike; Want een deel uut Oestrike Quamen, met groter partien, Ende uten lande van Hongherien, Jonc, out, clein ende groot, Om die vrese van der doot. Leke, papen, ende clercken Quamen, met hopen even sterke, Ute oeste al int weste, Uut menighe stat ende veste. Si ghinghen xxxiij daghe Ende enen halven; met selke slaghe Sloeghen si op haer lijf al bloet, Dattert bloet uut liep al roet,... |

("In the days of Duke John [III of Brabant] The holy church had much to suffer And bear hardship; For a part out of Austria Came [people], with great groups, And from the lands of Hungary, Young, old, small and tall, For the fear of death. Lay people, priests, and clerics Came, with heaps equally strong, From the east to the west, From many a city and [fortified] town. They went for 33 days And half a day; with the same stroke They beat their [own] naked bodies So that blood ran out of it, all red...") |

| – On the Flagellants. Brabantsche Yeesten V.[10] | (translation) |

The story goes on to narrate that Jews were "also done pain here in Brabant", because they allegedly had used "venom" (fenine) "in many cities, in order to spoil Christendom, therefore the Jews had to die."[10] Duke John is then said to have all Jews arrested (va[ng]en, "caught"), whom were "burnt, beaten or drowned", ending that this all happened in the years 1349 and 1350.[10] The Boec vander wraken ("Book of Wraths"), written by an unknown Antwerp author (probably also Jan van Boendale) between 1346 and 1351, reports many details of the plague in the region, as well as flagellants, although it makes no specific mention of events in Antwerp itself.[9] "The disease began in Babel, I was assured, and soon spread across the Mediterranean in southern Italy, Calabria, Sicily, Cyprus, Tuscany, Lombardy, in Romagna, thence to France and from France to England," the Boec claims.[9] Entire villages are depopulated, and local governments and courts ceased to function.[9] In one anecdote from Utrecht, there was a mansion whose inhabitants and cattle had all died; two burglars stole some jewellery from the building, after which one of them died as well.[9] The author had a double explanation for the plague, believing it to be both a divine punishment, as well as a plot by the Jews to poison the drinking waters; therefore, he condoned the anti-Jewish pogroms.[9]

The Rhymed Chronicle of Flanders (probably written around 1410 in Ghent), as preserved early-15th century Comburg Manuscript, noted that between 1348 and 1350, there was die groete steerfte ("the great dying"):[11]

| ...Dit ghesciede alsmen screef vorwaer XIIIc ende XLVIII iaer Curt hier naer si hu becant Quamen die cruus broeders int lant Ende daernaer die groete steerfte was Kerstinede duere gheloeft mi das Ende int iaer L dat verstaet So was te roeme tgroete aflaet... |

("...This happened when they truly wrote 1300 and 48 years Shortly thereafter, as you know The Cross Brothers came into the land And after that was the great dying Throughout Christendom, believe you me And in the year [13]50, you see There was in Rome the great jubilee...) |

| – Rhymed Chronicle of Flanders[11] | (translation) |

"In the year 1349, God from the heavenly realm chastised the whole world with a great, heavy pestilence, so that barely half of all people remained alive, and that many cities and villages and castles stood empty and uninhabited. Because of this great heavy plague and dying, in many places arose, without any authority or precedent from the pope or the holy church, some people which adopted a public penitence, which were called the flagellant brothers..."

It is known that the plague went as far as Hainaut and Flanders in the summer of 1349, but its progress further North cannot be traced, and there is no documentation of it in Central Netherlands. It is however confirmed that the ongoing reclaim of wetlands in Holland discontinued at this point, possibly because the population was suddenly smaller and there was, therefore, enough land for everyone.[1]

The very northern part of the Netherlands, Frisia, is documented to have been reached by the plague, where it came from Germany in 1350, and there is a description of it in Deventer and Zwolle.[1] In Zwolle, a dispute even occurred between religious authorities as to who had the right to perform mass burials.[13]

Bohemia

[edit]According to the traditional narrative, Bohemia was spared from the Black Death. This was also used as propaganda. Since the Black Death was commonly interpreted as a divine punishment for the Sins of humanity, the fact that Bohemia was spared was a great gain for the reputation of Bohemia, and the Bohemian elite and government made use of this. In the famous chronicle Cronica Boemorum regum by Francis of Prague (Franciscus Pragensis), the king and the Kingdom of Bohemia were portrayed as free from the sins God's had sent the plague to punish the rest of Europe for, and the air as pure and clear.[1] With the exception of local outbreaks in Brno and Znojmo in Moravia in December 1351, no contemporary sources contradict the contemporary claim that Bohemia was spared.[1] Archaeological research suggests that the Black Death might have been responsible for some of the mass burials at Sedlec Ossuary.[14]

The reason why Bohemia was spared from the plague is debated. It has been suggested, that since Bohemia lacked water ways and could only be reached by land; and that most of the traffic came to Bohemia from Germany, where all traffic collapsed because of the Black Death there, the fact that the traffic from Germany was interrupted by the plague resulted in an unintentional quarantine, which spared Bohemia.[1]

Consequences

[edit]

The Holy Roman Empire was the stage for both the Jewish pogroms as well as the flagellants during the Black Death.[1]

As the plague progressed, the Jews were accused to have caused it by well poisoning. Rumours of well poisoning were spread in France, but they were directed more toward Jews within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire, where there was a larger Jewish population than in France.[1] The persecutions started to cause mass trials and mass executions of Jews in the Duchy of Savoy, and turned into massacres when the rumours of the trials in Savoy reached Switzerland and Germany.[1]

According to the chronicler Heinrich von Diessenhoven, all Jews from Cologne to Austria were killed in a series of massacres between November 1348 and September 1349.[1]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In dem vurz jair ind zwey jair dairnae was eyn groiss sterffde alle die werlt durch in heydenschafft ind in Cristenheit. Quoted from Cronica vander hiliger stat Coellen, fol. 278v.

- ^ Middle Dutch sources use phrases such as groitte starfte, die groete steerfte, eyn groiss sterffde, or dese grote sware plage ende sterfte. The modern Dutch noun sterfte and verb sterven are cognates of the English verb to starve. However, at some point the Dutch words acquired a more general meaning of death, dying and to die, rather than death caused by starvation, that is, a lack of food consumption. Therefore, it is not always linguistically clear from Middle Dutch sources whether the authors attribute death to starvation specifically, or to other or unknown causes in general. The same applies to High German words sterben and Sterben.

- ^ In dem vurz iair up Sent Bartholomeus dach verbranten sich die Joeden selffs zo Coelne in yren huyseren (...) want Sy die wasser und puyz [?] venynt hadden / und hadden dat bestalt durch die Cristenheit. So wurden Sy do men ide wijss wart verstoert, verdreuen und veriaget uyss Coellen in vigilia Bartholomei. Quoted from Cronica vander hiliger stat Coellen, fol. 279v.

- ^ "Jnt Jaer .M.CCC.xlix. heeft god van hemelrijck alle die werelt gecastijt mit een grote sware pestilencie dat de helft van allen menschen nauwelijc te lijue ghebleuen en is, also datter vele steden dorpen ende sloten leech ende onbewoent bleven staen. Door dese grote sware plage ende sterfte zijn in veel plaetsen op ghestaen sonder eenige auctoriteyt oft outheyt vanden paus oft der heyliger kercken eenige menschen aennemende een openbaer penitencie, die ghenoemt waren die gheselbroeders..." Chapter XLIII. Van Brabant die excellente cronike (1530), originally published in 1497 as Die alderexcellenste cronyke van Brabant.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Oosterman, Johan (7 May 2020). "Wanttet was groitte starfte. De pest door ooggetuigen uit de Lage Landen" ['Because there was great dying'. The plague by eyewitnesses from the Low Countries]. Neerlandistiek (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d Jan van Boendale (1869). "Van den gheesselaren., Brabantsche yeesten. Les gestes des ducs-de-Brabant par Jean de Klerk d'Anvers". dbnl.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ a b Brinkman, Herman; Schenkel, Schenkel (1997). Het Comburgse handschrift. Hs. Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. poet. et phil. 2° 22. Volume 2 (PDF) (in Dutch). Hilversum: Verloren. p. 1449.

- ^ Anonymous (2016). "Van Brabant die excellente cronike. Dat .xliij. capitel. Vanden geselbroeders" [The Excellent Chronicle of Brabant. The 43rd chapter. On the flagellant brothers.]. dbnl.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ Bendictow's The Black Death, 1346-1353, pg 205.

- ^ Horak, Jan et al. (2022). The Cemetery and Ossuary at Sedlec near Kutna Hora: Reflections on the Agency of the Dead. Interdisciplinary Explorations of Postnortem Interaction 269.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Swedish. (May 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|