Black Book (film)

| Black Book | |

|---|---|

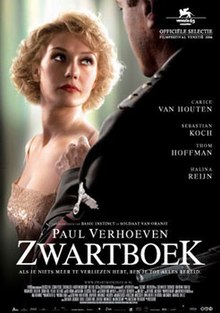

Theatrical release poster | |

| Dutch | Zwartboek |

| Directed by | Paul Verhoeven |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Walter Lindenlaub |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Anne Dudley |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 146 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $21 million[1] |

| Box office | $27 million[1] |

Black Book (Dutch: Zwartboek) is a 2006 war drama thriller film co-written and directed by Paul Verhoeven, and starring Carice van Houten, Sebastian Koch, Thom Hoffman and Halina Reijn. The film, credited as based on several true events and characters, is about a young Jewish woman in the Netherlands who becomes a spy for the resistance during World War II after tragedy befalls her in an encounter with the Nazis. The film had its world premiere on 1 September 2006 at the Venice Film Festival and its public release on 14 September 2006 in the Netherlands. It is the first film that Verhoeven made in his native Netherlands since The Fourth Man, made in 1983 before he moved to the United States.

The press in the Netherlands was positive; with three Golden Calves, Black Book won the most awards at the Netherlands Film Festival in 2006. The international press responded positively, as well, especially to the performance of Van Houten. It was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language, and was the Dutch submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2007, making the January shortlist.

It was three times more expensive than any Dutch film ever made, and also the Netherlands' most commercially successful, with the country's highest box-office gross of 2006. In 2008, the Dutch public voted it the best Dutch film ever.[3]

Plot

[edit]In 1944, Dutch Jewish singer Rachel Stein is hiding in the occupied Netherlands. When the farmhouse where she had been hiding is destroyed by an Allied bomber, she goes to see a lawyer named Smaal who had been helping her family. He arranges for her to escape to the liberated southern part of the country. Aided by a man named Van Gein, Rachel is reunited with her family and boards a boat that is to take them and other refugees to the south. They are ambushed by the German SS who kill them and rob valuables from the bodies. Rachel alone survives but does not manage to escape from the occupied territory.

Using a non-Jewish alias, Ellis de Vries, Rachel becomes involved with a resistance group in The Hague, under the leadership of Gerben Kuipers and working closely with a doctor, Hans Akkermans. Smaal is in touch with this Resistance cell. When Kuipers's son and other members of the Resistance are captured, Ellis agrees to help by seducing local SD commander Hauptsturmführer Ludwig Müntze. During a party at SD headquarters, Ellis recognises Obersturmführer Günther Franken, Müntze's brutal deputy, as the officer who had overseen the massacre on the boat. She obtains a job at the SD headquarters while falling in love with Müntze who, in contrast to Franken, is not abusive or sadistic. He realises that she is a Jew but does not care.

Thanks to a hidden microphone that Ellis plants in Franken's office, the Resistance realises that Van Gein is the traitor who betrayed Rachel, her family, and the other Jews. Against Kuipers's orders, Akkermans decides to abduct Van Gein to expose him. Their attempt goes wrong, and Van Gein is killed. Franken responds by planning to kill 40 hostages, including most of the plotters but Müntze, who realises the war is lost and has been negotiating with the Resistance, countermands the order.

Müntze forces Ellis to tell him her story. On her evidence, he confronts Franken with a superior officer, Obergruppenführer Käutner, who orders Franken to open his safe, expecting to find the valuables stolen from the Jews he had killed, this being a capital offense. The safe contains no valuables and Franken then tells Käutner that Müntze has been negotiating with the resistance for a truce. Müntze is imprisoned and condemned to death. The resistance plot to rescue their imprisoned members; Ellis agrees to cooperate only on the condition that they also free Müntze. The plan is betrayed and the rescuers find the prisoners' cells filled with German troops. Only Akkermans and one other man manage to flee.

Ellis is arrested and taken to Franken's office. He knows about her and the microphone and, knowing that the resistance members are listening, he stages a confrontation to make them believe that Ellis is the collaborator responsible for the failure of the rescue. Kuipers and his companions swear to make her pay for her treason. Ronnie, a Dutch woman working at the SD headquarters to whom Ellis had confided her role in the resistance, helps her and Müntze escape.

When the country is liberated by the Allies, Franken attempts to escape by boat but is killed by Akkermans, who takes the Jewish loot. Suspecting Smaal is the traitor, Müntze and Ellis return to confront him. Smaal states that the identity of the traitor is evidenced by his 'black book', in which he had detailed all his dealings with Jews. He refuses to discuss it further, wanting to go to the Canadian authorities. When they are about to leave, Smaal and his wife are killed by an unknown assailant. Müntze chases him into the street, only to be recognised by the Dutch crowd and arrested by soldiers from the Canadian Army. The Dutch also recognise Ellis and arrest her as a collaborator but not before she grabs the black book.

Müntze is brought before the Canadian officers and finds that Käutner is helping to keep order among the defeated German forces. Käutner convinces a Canadian colonel that under military law, the defeated German military retains the right to punish its own soldiers. Due to the German death warrant, Müntze is executed by a firing squad.

Ellis is imprisoned with accused collaborators, humiliated and tortured by the violently anti-Nazi volunteer jailers but rescued by Akkermans, who is now a colonel in the Dutch Army. Akkermans brings her to his medical office and says that he killed Franken when the Nazi tried to escape. He shows her the valuables stolen from Jewish victims. When informed about Müntze's fate, Ellis goes into shock and Akkermans administers a tranquilliser which is in fact an overdose of insulin. Ellis, feeling dizzy, sees the bottle of insulin and survives by quickly eating a bar of chocolate. She realises then that Akkermans is the traitor who had collaborated with Franken and had killed the Smaals. While Akkermans is distracted, waving to a crowd that cheers him, she jumps from the balcony into the crowd below and runs away. He tries to follow but is blocked by the crowd.

Ellis proves her innocence to Canadian military intelligence and the former Resistance leader Gerben Kuipers through Smaal's black book, which lists how many Jews had been taken to Akkermans for medical help just prior to their murder. Ellis and Kuipers intercept the fleeing Akkermans, hiding in a coffin in a hearse with the stolen money, gold, and jewels. They beat the driver, and while Kuipers drives the hearse, Ellis screws down the coffin's secret air vents. They drive to Hollands Diep where the original SS trap had been sprung and wait until Akkermans suffocates. Ellis and Kuipers wonder what to do with the stolen money and jewels.

The scene changes to Israel in 1956, reprising the opening scenes and shows Rachel meeting her husband and their two children, walking back into Kibbutz Stein, with a sign at the gate announcing that it was funded with recovered money from Jews killed during the war. In the final scene, the tranquillity of Rachel and her family is interrupted by explosions heard in the distance; the siren announces an air attack and Israeli soldiers position themselves at the front of the kibbutz.

Cast

[edit]

- Carice van Houten as Rachel Stein, alias Ellis de Vries

- Sebastian Koch as Ludwig Müntze (SS-Hauptsturmführer)

- Thom Hoffman as Hans Akkermans

- Halina Reijn as Ronnie

- Waldemar Kobus as Günther Franken (SS-Obersturmführer)

- Derek de Lint as Gerben Kuipers

- Christian Berkel as General (SS-Obergruppenführer) Käutner, superior of Günther Franken and Ludwig Müntze in the Sicherheitsdienst

- Dolf de Vries as Mr. Smaal, attorney who keeps the black book

- Peter Blok as Mr. Van Gein, policeman who betrays those trying to leave occupied territory

- Michiel Huisman as Rob, sailor who helps Rachel Stein

- Ronald Armbrust as Tim Kuipers, son of Gerben Kuipers, a communist, and a member of the resistance group

- Frank Lammers as Kees, member of the resistance group

- Matthias Schoenaerts as Joop, member of the resistance group

- Xander Straat as Maarten, member of the resistance group

- Johnny de Mol as Theodore, member of the resistance group

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]

After 20 years of filmmaking in the United States, Verhoeven returned to his homeland, the Netherlands, for the making of Black Book. The story was written by Verhoeven and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman, with whom he made successful films such as Turkish Delight (1973) and Soldier of Orange (1977). The two men had been working on the script for fifteen years,[4] but they solved their story problems in the early 2000s by changing the main character from male to female. According to Verhoeven, Black Book was born out of elements that did not fit in any of his earlier movies, and it can be seen as a supplement to his earlier film about World War II Soldier of Orange.[5]

Verhoeven has emphasised that the story does not show an obvious moral contrast between characters, for a theme of moral relativism:

In this movie, everything has a shade of grey. There are no people who are completely good and no people who are completely bad. It's like life. It's not very Hollywoodian.[6]

Black Book is not a true story, unlike Soldier of Orange, but Verhoeven states that many of the events are true.[7] As in the film, the German headquarters were in the Hague. In 1944 many Jews that tried to cross to liberated parts of the southern Netherlands were entrapped by Dutch policemen. As in the film, crossing attempts took place in the Biesbosch.[5] Events are related to the life of Verhoeven, who was born in 1938 and grew up in the Hague during the Second World War.[8] The execution of Müntze by German firing squad after the war had ended echoes the notorious May 1945 German deserter execution incident.

Financing

[edit]The initial estimate of the budget for making Black Book was €12,000,000. According to film producer Rob Houwer, who worked with Paul Verhoeven on previous films, it was not possible to get the job done for that amount of money. San Fu Maltha produced the film together with three other producers. He tried to economize on different parts such as the scenes in Israel, that could have been left out without changing the plot, but this was not negotiable for Paul Verhoeven.[4]

Because of financing problems, the filming did not start as planned in 2004 but was delayed until August 2005.[9][10] In this month it was announced that Black Book received about €2,000,000 support from the Netherlands Public Broadcasting, the CoBO Fund, and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.[11] There were also several foreign investors, which made the film a Belgian, British, and German coproduction. With a final estimated budget of €18,000,000, the film was the most expensive Dutch film ever, at the time of its release.[4]

In October 2006 twelve crew members and businessmen started a lawsuit in which they demanded the bankruptcy of Zwartboek Productie B.V., the legal entity founded for the film. Some of them had already been waiting for more than a year to get their money, in total tens of thousands of euros. Production company Fu Works settled the case and promised to pay the creditors.[12]

Filming

[edit]

The shooting of the film was delayed in 2004 due to financial problems[9] and Paul Verhoeven's health problems.[13] Because of the delay there was a lawsuit regarding lead actress Carice van Houten, who had agreed to act in a play. When van Houten was forced to return to the set, the theater company sued over the costly delay to their own production. The outcome of the lawsuit was that the production company had to pay €60,000 for her unavailability.[14]

Principal photography took place from 24 August until 19 December 2005[15] on locations in the Netherlands, including Hardenberg, Giethoorn, the Hague, Delft and Dordrecht, and in Israel, by Hocus Focus Films.[16] In the opening scene a real pre-war farm was blown up in the municipality of Hardenberg. The farm had already been declared uninhabitable and ready to be demolished.[17] Some underwater explosions were filmed in a lake near Giethoorn.[18] In the centre of The Hague they built bunkers to cover up modern day objects such as the entrance to an underground car park.[19] The former chemistry faculty building of the Delft University of Technology was used to film prison scenes. Great attention to detail was paid in the film. Several stage props were reproduced from the 1940s, such as signs, posters and the black book itself.[20] Furthermore, in one of the liberation scenes in The Hague, up to 1,200 extras appeared.[21]

During shooting, the general public was able to see "making of" scenes on their mobile phones and on the internet.[22]

Historic background

[edit]The story of the Jewish woman Rachel Stein in Zwartboek is based on Dutch resistant fighter Esmée van Eeghen.[23] Van Gein was based on the lives of Ans van Dijk and Andries Riphagen. Notary Smaal is based on the unsolved murder of 65-year-old lawyer H. de Boer in The Hague on 30 May 1945 (shortly after the liberation). During the war, de Boer appeared to have maintained good contacts with the German Sicherheitsdienst.[24]

Media based on the film

[edit]Novelisation

[edit]The screenplay by Paul Verhoeven and Gerard Soeteman was turned into a thriller novel by Dutch writer Laurens Abbink Spaink. The book was published in September 2006 by Uitgeverij Podium and contains photos and an afterword by Verhoeven and Soeteman. Spaink says about the book: "Black Book is a literary thriller. Its form is in between the typical American novelisation, only describing what the camera sees, and a literary novel. The novelisation adds something to the film. It gave Rachel Stein a past, memories and a house. In the film she did not have a personal space."[25]

Soundtrack

[edit]The soundtrack was released on 2 October 2006 by Milan Records. The album contains four 1930s–1940s songs sung by Carice van Houten as she performed them as Rachel Stein in the film. Three are in German, one in English. The other tracks are written by Anne Dudley. The album was recorded in London and produced by Roger Dudley.[26]

Reception

[edit]Premieres and festivals

[edit]

Black Book had its world premiere on 1 September 2006 in Venice, as part of the official selection of the Venice International Film Festival.[27] Here it was nominated for a Golden Lion and won the Young Cinema Award for best international film.[28] The film was also in the official selection of the 2006 Toronto Film Festival.[citation needed]

The Prince of Orange and his wife Princess Máxima attended the Dutch gala premiere of Black Book in the Hague on 12 September 2006. Other prominent guests at the premiere were mayor Wim Deetman, minister Hans Hoogervorst, minister Karla Peijs and state secretary Medy van der Laan.[29]

The film was nominated for four Golden Calves at the Netherlands Film Festival in 2006. It won in three categories: the Golden Calf for Best Actress (Carice van Houten), for Best Director (Paul Verhoeven), and for Best Film (San Fu Maltha). Black Book was the most awarded film of the 2006 festival.[30]

The United States premiere of Black Book was a gala screening at Palm Springs High School on 5 January 2007 during the Palm Springs International Film Festival.[31] On 2 March 2007, Black Book was the opening film of the Miami International Film Festival.[32]

The German premiere of Black Book was a gala screening at Zoo Palast in Berlin on 9 May 2007.[citation needed]

Critical reception

[edit]Most of the Dutch press were positive about the film. Dana Linsen writes in NRC Handelsblad: "In Black Book, Verhoeven does not focus on moral discourse but rather on human measure, and with the non-cynical approach of his female lead and of love he has given new colour to his work."[33] Belinda van de Graaf in Trouw writes: "Breathless we run along burning farms, ugly resistance fighters, pretty kraut whores, spies, traitors, and because the story has to go on the coincidences pile up until it makes you laugh. When Carice van Houten screams 'Will it never stop, then!' it is almost kitsch, and not surprisingly already a classic film quote."[34] She compares this film to Soldier of Orange and explains why this film is not a stereotypical war film: "The war adventure is no longer based on the male character of the type Rutger Hauer, with his machismo and testosterone, but the small fighter Carice van Houten".[34] Literary critic Jessica Durlacher, daughter of an Auschwitz survivor, describes the film in Vrij Nederland with the following comparison: "The reality of 1940–1945 as portrayed in Black Book compared to reality is like the Eiffel Tower in Las Vegas compared to the original in Paris."[35]

The international press wrote positively about the film and specifically about van Houten.[36] The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports a 76% "fresh" rating based on 160 reviews, with an average score of 7.1/10; the general consensus states: "A furious mix of sex, violence, and moral relativism, Black Book is shamelessly entertaining melodrama.".[37] Metacritic reported the film had an average score of 71 out of 100, based on 34 reviews.[38] According to Jason Solomons in The Observer: "Black Book is great fun, an old-fashioned war movie in parts, but with deep undercurrents about fugitive Jews, the Resistance, collaborators and the messy politics of war. This being Verhoeven, there's lots of sex and a scene in which the extremely attractive star (Carice van Houten) bleaches her pubic hair. That aside, hers is a star-making performance, putting even Scarlett [Johansson] in the shade."[39] In the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Dirk Schümer says Carice van Houten is not only more beautiful, but also a better actress than Scarlett Johansson. Furthermore, he writes in his review: "Europe's Hollywood can actually be better than the original. With his basic instinct sharpened in California, Verhoeven demonstrates here the cinema as a medium of individual tragedy."[40] Jacques Mandelbaum writes in his review in Le Monde: "This lesson about humanity and about fear can be situated in the wake of several rare masterpieces, that are solemnly confronted by this story";[41] he also compares Black Book with classics like The Great Dictator, To Be or Not to Be, and Monsieur Klein.

Richard Schickel of Time named the film one of the Top 10 Movies of 2007, ranking it at #5, calling it a "dark, richly mounted film". While Schickel saw the film as possibly "old-fashioned stylistically, and rather manipulative in its plotting", he also saw "something deeply satisfying in the way it works out the fates of its troubled, yet believable characters."[42]

Commercial success

[edit]Before the film was released, the rights for distribution had been sold to distributors in 52 countries.[43] According to the production company Fu Works these sales made the film Black Book commercially the most successful Dutch film production ever, at the time of its release.[44]

Black Book received a Golden Film (100,000 tickets sold) within a record-breaking three days[45] and a Platinum Film (400,000 tickets sold) within three weeks after the Dutch premiere.[46] The film had its millionth visitor on 12 January 2007 and was the first film to receive a Diamond Film award.[47]

Black Book had the highest box office gross for a Dutch film in 2006, coming third overall in 2006 in the Netherlands, after the American films Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and The Da Vinci Code.[48] As of 31 December 2006, the box office gross in the Netherlands was €6,953,118.[49]

Top ten lists

[edit]The film appeared on several critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2007.

- 1st – Jonathan Rosenbaum, Film Comment[50]

- 3rd – James Coleman, The 213[51]

- 5th – James Berardinelli, ReelViews[52]

- 5th – Richard Schickel, Time[52]

- 8th – Nathan Lee, The Village Voice[52]

- 9th – Scott Tobias, The A.V. Club[52]

Awards and nominations

[edit]- Nomination Golden Lion (2006)[27]

- Young Cinema Award for Best International Film (2006)[27]

- Golden Film for 100,000 visitors in the Netherlands (2006)[45]

- Platinum Film for 400,000 visitors in the Netherlands (2006)[46]

- Golden Onion for Worst Actor (2006) for Johnny de Mol[53]

- Nomination Golden Calf for Best Supporting Actress (2006) for Halina Reijn[54]

- Golden Calf for Best Actress (2006) for Carice van Houten[30]

- Golden Calf for Best Director (2006) for Paul Verhoeven[30]

- Golden Calf for Best Film (2006) for San Fu Maltha[30]

- Nomination London Film Critics' Circle Award for Foreign Language Film of the Year (2006)[55]

- The Hague Public Award 2006 for contributing to a positive image of The Hague[56]

- Nomination British Academy Film Award for Best Film Not in the English Language (2007)[57]

- Dutch submission for the Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (2007);[58] was on the shortlist, but not among the five nominees[59]

- Diamond Film for 1,000,000 visitors in the Netherlands (2007)[60]

- Nomination Saturn Award for Best Actress for Carice van Houten (2008)[61]

- Nomination Saturn Award for Best International Film (2008)[61]

See also

[edit]- List of Dutch submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of submissions to the 79th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Black Book (2007) Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "ZWARTBOEK - BLACK BOOK (15)". Tartan Films. British Board of Film Classification. 18 October 2006. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Zwartboek beste film aller tijden - Cinema.nl Nieuws" (in Dutch). Cinema.nl. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Berkhout, Karel; Blokker, Bas (8 September 2006). "Kan niet bestaat niet". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ a b De Wereld Draait Door Archived 13 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine - Paul Verhoeven talks about the film, 7 September 2006

- ^ "Homeward bound". the Guardian. 25 November 2005.

- ^ "The events are true, the story is not.", translated quote of Paul Verhoeven from 'Zwartboek' heeft geen ruimte voor subtiliteit Archived 17 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine in NRC Handelsblad.

- ^ "Een beetje oorlog, best spannend". Ethesis.net. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Opnames Verhoevens Zwartboek uitgesteld". Filmfocus.nl. 14 October 2004. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2006. (in Dutch)

- ^ "Shooting Paul Verhoevens Black Book will start end of August". Fu Works. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ "Zwartboek en Alles is Liefde krijgen financiële steun". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 30 August 2005. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ "Faillissement Zwartboek afgewend na schikking". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 27 October 2006. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ "Paul Verhoeven ziek, opnamen Zwartboek uitgesteld". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 27 October 2004. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "'Zwartboek' moet betalen". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 3 February 2006. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Business Data for Zwartboek". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ "Filming in Israel - Hocus Focus Films". 9 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Verhoeven mag boerderij in Hardenberg opblazen". Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 25 October 2005. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Verhoeven krijgt toestemming voor explosies". Trouw (in Dutch). 24 September 2005. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ Photocapy (13 November 2005). "Entrance to a parking garage disguised as a bunker". Flickr. Retrieved 5 December 2006.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Hoffman, Thom (27 November 2006). De Wereld Draait Door (talkshow). Netherlands: VARA. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "Acteur Thom Hoffman laat mensen Zwartboek beleven". Dagblad van het Noorden (in Dutch). 4 May 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Opnames Zwartboek via Vodafone op mobiel" (Press release). Fu Works. 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Eeghen, Esmée van". Huygens ING en OGC (UU) (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Zwartboek". Ghent University (in Dutch). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Van Baars, Laura (15 September 2006). "De 'verboeking' van Zwartboek". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ De Bruijn, Joep. "Review". Filmscore visions. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ a b c Stigter, Bianca (2 June 2006). "'Zwartboek' heeft geen ruimte voor subtiliteit". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ "Awards for Zwartboek". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ "Zwartboek beleeft Nederlandse première". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Zwartbroek grote winnaar Film Festival". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Dutch). 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ "Black Book". Palm Springs International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ "Miami International Film Festival Announces 2007 Film Program" (PDF) (Press release). Miami International Film Festival. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ Linssen, Dana (13 September 2006). "'Zwartboek' walst grijs verleden uit". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ^ a b Graaf, Belinda van de (14 September 2006). "Carice van Houten als kleine krachtpatser in Verhoevens 'Zwartboek'". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ Durlacher, Jessica (16 September 2006). "Zwartboek liegt". Vrij Nederland (url is not the original source). Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2006. (in Dutch)

- ^ Stigter, Bianca (4 September 2006). "Carice van Houten slaat in als een bom". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ "Black Book". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Black Book (2007)". Metacritic. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Solomons, Jason (3 September 2006). "Water, water everywhere - and a flood of tears". The Observer. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ Schümer, Dirk (1 September 2006). "Basisinstinkt: Paul Verhoevens "Schwarzbuch" in Venedig". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Jacques (28 November 2006). ""Black Book": Paul Verhoeven brouille les pistes du bien et du mal". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (9 December 2007). "Top 10 Movies". Time. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "Official website".

- ^ "Zwartboek nu al succesvolste Nederlandse film ooit". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 21 August 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ a b "Zwartboek bekroond met de Gouden Film". 18 September 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006. (in Dutch)

- ^ a b "Zwartboek bekroond met de Platina Film tijdens Gala van de Nederlandse Film". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006. (in Dutch)

- ^ "Zwartboek passeert de 1 miljoen bezoekers". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 12 October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ Goodfellow, Melanie (22 December 2006). "Verhoeven leads Dutch resistance". Variety.com. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ $9,125,272 = €6,953,118. "Netherlands Box Office. 28–31 December 2006". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 January 2006.

- ^ "Ten Best Lists, 2005–2009 - Jonathan Rosenbaum". www.jonathanrosenbaum.net. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021.

- ^ Jason Coleman's Top Ten Films of 2007 (29 December 2007). Retrieved on 12 January 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Metacritic: 2007 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ^ "En de winnaars zijn..." degoudenui.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 January 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "A-film oogst 27 Gouden Kalf nominaties". a-film.nl (in Dutch). A-Film. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ "Dames get ready to do battle at film critics' awards" (Press release). NSPCC. 18 December 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ "Zwartboek wint Haagse publieksprijs". De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- ^ "This year's nominees". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ "Black Book official entry from the Netherlands for Best Foreign Language film". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ^ Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (16 January 2007). "Nine Foreign Language Films Seeking 2006 Oscar". Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- ^ "Eerste Diamanten Film voor Zwartboek" (Press release). Nederlands Film Festival. 29 January 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ a b Saturn Awards. Retrieved on 23 February 2008.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Dutch)

- Black Book at IMDb

- Black Book at the TCM Movie Database

- Black Book at AllMovie

- Black Book at Rotten Tomatoes

- Black Book at Box Office Mojo

- Black Book at Metacritic

- 2006 films

- 2000s spy thriller films

- 2000s war drama films

- German spy thriller films

- British spy thriller films

- Belgian spy thriller films

- Canadian Armed Forces in films

- 2000s Dutch-language films

- 2000s German-language films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s Hebrew-language films

- Films directed by Paul Verhoeven

- Films set in 1944

- Films set in 1956

- Films set in Israel

- Films set in the Netherlands

- Films shot in Germany

- Films shot in Israel

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in the Netherlands

- Western Front of World War II films

- Babelsberg Studio films

- World War II spy films

- Films scored by Anne Dudley

- British World War II films

- German World War II films

- Dutch World War II films

- A-Film Distribution films

- Sony Pictures Classics films

- 2006 multilingual films

- Dutch multilingual films

- German multilingual films

- British multilingual films

- Belgian multilingual films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s German films

- Films about Dutch resistance

- Best Feature Film Golden Calf winners

- 2000s Belgian films

- Films set in Amsterdam

- Films shot in Amsterdam

- English-language war drama films

- English-language spy thriller films