Roman Catholic Diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay

Diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay Dioecesis Aniciensis Diocèse du Puy-en-Velay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Ecclesiastical province | Clermont |

| Metropolitan | Archdiocese of Clermont |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 5,001 km2 (1,931 sq mi) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2021) 232,900 (est.) 182,500 (est.) |

| Parishes | 279 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | 3rd Century |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of Notre Dame in Le Puy-en-Velay |

| Patron saint | Notre Dame |

| Secular priests | 101 (diocesan) 8 (Religious Orders) 15 Permanent Deacons |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Yves Baumgarten |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | François Kalist |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| Website of the Diocese | |

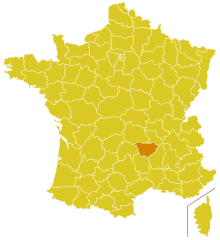

The Diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay (Latin: Dioecesis Aniciensis; French: Diocèse du Puy-en-Velay [djɔsɛz dy pɥi ɑ̃ vəlɛ]) is a Latin diocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese comprises the whole Department of Haute-Loire, in the Region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.

The diocese was originally a suffragan (subordinate) of the archdiocese of Bourges. By the 11th century it had become a direct suffragan of the papacy. The old Diocese of Le Puy was suppressed by the Concordat of 1801, and its territory was united with the Diocese of Saint-Flour. Le Puy became a diocese again in 1823. The district of Brioude, which had belonged to the Diocese of Saint-Flour under the old regime, was thenceforward included in the new Diocese of Le Puy. Since 2002, the diocese has been a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Clermont.

Le Puy is on the Way of St. James, the historical pilgrimage to Compostela.[1]

Early history

[edit]The town was originally named Vellavum, after the Gallic tribe. In the 12th century, it came to be called Le Puy (Podium Vellavorum); podium was the Gallic word for "mountain".[2]

The Martyrology of Ado and the first legend of Saint Front of Perigueux (written perhaps in the middle of the 10th century, by Gauzbert, chorepiscopus of Limoges) speak of a certain priest named George who was brought to life by the touch of St. Peter's staff, and who accompanied St. Front, St. Peter's missionary and the alleged first Bishop of Périgueux. A legend of St. George, the origin of which, according to Louis Duchesne is not earlier than the eleventh century, makes George one of the seventy-two disciples, and tells how he founded the Church of Civitas Vetula in the County of Le Velay, and how, at the request of St. Martial, he caused an altar to the Blessed Virgin to be erected on Mont Anis (Mons Anicius). When and how George is supposed to have become a bishop is not recorded.[3]

After St. George, certain local traditions of very late origin point to Sts. Macarius, Marcellinus, Roricius, Eusebius, Paulianus, and Vosy (Evodius) as bishops of Le Puy. It must have been from St. Paulianus that the town of Ruessium, now Saint-Paulien, received its name; and it was probably St. Vosy who completed the church of Our Lady of Le Puy at Anicium and transferred the episcopal see from Ruessium to Anicium. St. Vosy was apprised in a vision that the angels themselves had dedicated the cathedral to the Blessed Virgin, whence the epithet Angelic given to the cathedral of Le Puy. A notation in the page of a Sacramentary, which may have come from some liturgical book from Le Puy, gives the names: Evodius, Aurelius, Suacrus, Scutarius, and Ermentarius.[4] It is impossible to say whether this St. Evodius is the same who signed the decrees of the Council of Valence in 374. Neither can it be affirmed that St. Benignus, who in the seventh century founded a hospital at the gates of the basilica, and St. Agrevius, the seventh-century martyr from whom the town of Saint-Agrève Chiniacum took its name, were really bishops.

Duchesne thinks that the chronology of these early bishops rests on very little evidence and that very ill-supported by documents; before the tenth century only six individuals appear of whom it can be said with certainty that they were bishops of Le Puy. An inscription places Scutarius, the legendary architect of the first cathedral, at the end of the fourth century.

Growth in importance

[edit]The Church of Le Puy received, on account of its dignity and fame, temporal and spiritual favours. Concessions made in 919 by William the Young, Count of Auvergne and Le Velay, and in 923 by King Raoul (Rudolphus), gave it sovereignty over the whole population of the town (bourg) of Anis,[5] which was soon more than 30,000 people.[clarification needed] King Raoul's donation was confirmed by King Lothair in 955.[6]

In 1132, Pons, Count of Tripoli, gave the Church of Le Puy all the domaines that he possessed in the County of Velay. The grant was confirmed ten years later by his son, Raymond, Count of Tripoli.[7]

Pope Sylvester and Vellavensis ecclesia

[edit]In a council held in Rome by Pope Gregory V (996–999),[8] Bishop Stephan de Gévaudan (995–998) of Le Puy,[9] was condemned as an invasor of the see, and deposed from all ecclesiastical offices. He had been appointed by his predecessor and uncle, Bishop Guido of Anjou (975–993) while he was still alive, contrary to the wishes of the clergy and people. Stephanus was consecrated by two local bishops, contrary to the rule that the bishop-elect should be ordained by the pope.[10] The clear implication is that the archbishop of Bourges had lost a privilege over the Church of Le Puy, the right to consecrate a new bishop, and possibly the right to approve or disapprove the bishop-elect.

Sylvester II also granted the bishops of Le Puy a privilege which granted them security from excommunication or anathema (interdict) by any other bishop or royalty.[11]

Election of 1053

[edit]On 25 December 1051,[12] Pope Leo IX granted Bishop Stephanus de Mercour the right to wear the pallium on Christmas, the Epiphany, Holy Thursday, Easter, the Ascension, Pentecost, the feasts of S. Peter and S. Paul and S. Andrew, in all solemn feasts of the Virgin Mary, and the dedication of his cathedral. This was conditional on the observance of the rule that the bishops of Le Puy were to be consecrated by the pope.[13]

Bishop Stephanus de Mercour died at the beginning of 1053.[14] Dissension arose immediately between the clergy of the diocese and Henry I, King of the Franks (1031–1060)[15] The clergy, people, and nobility chose Petrus, the archdeacon and provost of the cathedral, and the nephew of the late bishop Stephanus, and informed the king that he was the one to be consecrated. The king put them off, despite interjections from those who were at the meeting in the presence of the king and bishops. Money was spread around, and the count of Toulouse and his wife put forward as bishop-elect Bertramnus, the Archdeacon of Mende. The cry of simony was immediately raised. The matter had to be referred to Pope Leo IX, who was in Ravenna at the time, on his journey from Germany to Rome.[16]

The delegation was headed by Archbishop Hugo of Besançon, Bishop Aimo of Sion (Switzerland), Bishop Artaldus of Grenoble, with the counsel of Archbishop Leodegarius of Vienne, who was a canon of Le Puy. They were received by the pope on 13 March 1053. After the documents of Pope Sylvester II and Pope Gregory V were read to him, he praised and confirmed the election of bishop-elect Petrus. Peter was ordained a priest by Cardinal Umbertus of Santa Rufina, and consecrated by the pope himself.[17]

Paschal II

[edit]On 25 March 1105,[18] Pope Paschal II issued the bull "Inter ceteras Francorum," confirming the privileges of Bishop Pontius de Tournon (1102–1112) and the diocese of Le Puy. The bull condenses the usual list of parishes and properties into the phrase "whatever is recognized as belonging to the diocese of Le Puy."[19] The pope instead directed his attention to the metropolitanate and to the pallium. He stated firmly that Le Puy was subject to nobody except the Roman see.[20] Bishop Pontius was granted the pallium, with instructions to use it at solemn Masses only on 15 specified days, and whenever he consecrated a church or ordained priests or deacons.[21]

It is presumed that the exclusive right of the Chapter of canons to elect a new bishop dates from the early 12th century,[22] but positive evidence is not found until 1190, when the Will of King Philip II of France, made at the beginning of his crusade, granted the right to all the Chapters in France.[23]

Religious Orders in Le Puy

[edit]In 1138, during the administration of Bishop Humbert D'Albon (1128–1144), two brothers, Raymond and Guillaume de Saint-Quentin, established a collegiate house of Canons Regular at Doue, a hilltop 5.5 km (3.1 mi) from Le Puy.[24] Due to disorders in the monastery, Bishop Pierre de Solignac (1159–1191) brought in the Canons Regular of Prémontré (Premonstratensians) in 1162.[25]

The Knights Templars had a priory in Le Puy by 1170, located just outside the eastern gate of the city. Their church and priory were dedicated in honor of Saint Bartholomew.[26] Persecution of their Order began in 1307, and examination of members from Le Puy began in Nîmes in June 1310 and continued in 1311.[27] The entire Order was abolished by Pope Clement V on 22 March 1312, though the members of Puy were absolved and received back into communion with the Church on 9 November 1312.[28]

The Dominicans (Order of Preachers) were established in Le Puy in 1221. Their house was blessed by Bishop Étienne de Chalencon (1220–1231) in October 1221. It is often said that Saint Dominic himself founded the house, but he had died on 6 August 1221, at the Dominican convent of S. Nicholas near Bologna (Italy). He had been working in Italy since 1218.[29]

Anthony of Padua, who died near Padua on 13 June 1231, had taught theology and led the Franciscan convent at Le Puy, probably c. 1224.[30]

Relationship with Catalonia

[edit]Tradition in the Velay asserts that the first bishop of Girona was a canon of Le Puy named Pierre.[31]

The canons of the chapter of Le Puy obtained a right to solicit funds for their hospital, a right established with the authorization of the Holy See in 1482,[32] in virtue of which the chapter levied a veritable tax[weasel words] in almost all the Christian countries.[citation needed]

In Catalonia this droit de quête, recognized by the Spanish Crown, was so thoroughly established that the chapter had its collectors permanently installed in that country. A famous "fraternity" existed between the chapter of Le Puy and that of Girona in Catalonia.[33]

Documentation of this relationship does not begin until the 15th century, and the connection with Charlemagne can be dated to 1345. It is based on liturgical sources. The papal bull was issued by Pope Sixtus IV in 1482.[34]

Later history

[edit]The bubonic plague reached the Midi in January 1348. It is claimed that one-third of the population in Velay were killed.[35]

In 1516, following the papal loss of the Battle of Marignano, Pope Leo X signed a concordat with King Francis I of France, removing the rights of all French entities which held the right to elect to a benefice, including bishoprics, canonicates, and abbeys, and granting the kings of France the right to nominate candidates to all these benefices, provided they be suitable persons; each nominee was subject to confirmation by the pope. This concordat removed the right of cathedral chapters to elect their bishop, or even to request the pope to name a bishop. The Concordat of Bologna was strongly protested by the University of Paris and by the Parliament of Paris.[36]

In 1562 and 1563 Le Puy was successfully defended against the Huguenots by priests and religious armed with cuirasses and arquebuses.[37] In 1760, there were about 5,000 Protestants in the diocese.[38]

In 1588, the Jesuits established the Collège du Puy.[39]

Bishop Just de Serres (1621–1641) held a diocesan synod in the church of S Voisy on 23 April 1623.[40] He held another synod in Spring 1627.[41]

Bishop Henri de Maupas du Tour (1643–1664) founded the house of the Religeuses de Nôtre-Dame de Refuge du Puy in 1644.[42]

In 1652, Bishop Henri de Maupas du Tour founded the grand seminary of Le Puy, and entrusted its operations to the Congregation of San Sulpice, headed by Jean-Jacques Olier.[43]

Bishop François-Charles de Beringhen D'Armainvilliers (1725–1742) allowed the Frères des Ecoles Chrétiennes to establish a presence in the diocese.[44]

French Revolution

[edit]One of the first acts of the French Revolution was the abolition of feudalism and its institutions, including estates, provinces, duchies, baillies, and other obsolete organs of government. On 28 October 1789, the National Constituent Assembly decreed the suspension of all vows, and on 13 February 1790, it decreed that vows were not to be taken. Religious orders and congregations which had vows, male and female, were dissolved.[45]

The National Constituent Assembly ordered their replacement by political subdivisions called "departments", to be characterized by a single administrative city in the center of a compact area. The decree was passed on 22 December 1789, the boundaries fixed on 26 February 1790, with the institution to be effective on 4 March 1790.[46]Le Puy was assigned to the Departement de l'Haute-Loire, in the new "Métropole du Sud-Est," with its administrative center at Clermont. The National Constituent Assembly then, on 6 February 1790, instructed its ecclesiastical committee to prepare a plan for the reorganization of the clergy. At the end of May, its work was presented as a draft Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which, after vigorous debate, was approved on 12 July 1790. There was to be one diocese in each department,[47] requiring the suppression of approximately fifty dioceses.[48] The suppression of dioceses by the state was uncanonical, and thus the Church considered the diocese without a bishop (sede vacante) from 1791 to 1801.[49]

The vast majority of the clergy of the diocese of Le Puy refused to take the oath required by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Nonetheless, a Constitutional bishop was "elected" by the approved electors of the new diocese of "Haute-Loire", a priest of the parish of Brioude named Étienne Delcher, whose brother was a member of the Convention and had voted for the execution of Louis XVI. He himself survived the Terror, and was able to protect most of his clergy, juring and non-juring. But he admitted in a letter of 10 May 1795, that he had only six or seven priests who had not fled the persecution inder The Terror.[50] In 1797, he was ill and therefore did not attend the assembly of the French clergy in Paris; he was also deserted by his vicars, who were without funds to continue their lives. In 1801, he was too ill to attend the council in Paris, and shortly thereafter he resigned his bishopric.[51] He never retracted his crimes and sins, and died in his brother's home on 17 August 1806.[52]

Suppression

[edit]On 29 November 1801, in the concordat of 1801 between the French Consulate, headed by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, and Pope Pius VII, the bishopric of Le Puy and all the other dioceses in France were suppressed. This removed all the contaminations and novelties introduced by the Constitutional Church.[53] The pope then, in the bull "Qui Christi Domini", recreated the French ecclesiastical order, respecting in most ways the changes introduced during the Revolution, including the reduction in the number of archdioceses and dioceses. The diocese of Le Puy was not restored, and its territory was incorporated into the diocese of Clermont.[54]

Restoration

[edit]The concordat of 27 July 1817, between King Louis XVIII and Pope Pius VII, should have restored the diocese of Le Puy by the bull "Commissa divinitus",[55] but the French Parliament refused to ratify the agreement. It was not until 6 October 1822 that a revised version of the papal bull, "Paternae Charitatis" ,[56] received the approval of all parties. The diocese of Le Puy became a suffragan of the archdiocese of Bourges.[57]

A provincial council was held at Clermont in October 1873. It was summoned by Cardinal Jacques-Marie-Antoine-Célestin du Pont, Archbishop of Bourges, and was attended by Bishop Joseph-Auguste-Victorin de Morlhon of Le Puy (1846–1862).[58]

Gustave Delacroix de Ravignan, in 1846, and Théodore Combalot, in 1850, were inspired with the idea of a great monument to the Blessed Virgin on the Rocher Corneille. Napoleon III placed at the disposal of Bishop Morlhon 213 pieces of artillery taken by Pélissier at Sebastopol, and the colossal statue of "Notre-Dame de France" cast from the iron of these guns, was dedicated on 27 September 1860, by the Cardinal Archbishop of Bordeaux, the archbishops of Tours and of Albi, and nine other bishops.[59]

Cathedral

[edit]The cathedral of Nôtre-Dame du Puy, which forms the highest point of the city, rising from the Rocher Corneille, exhibits architecture of every period from the fifth century to the fifteenth.[60]

The cathedral was administered by a corporation called the Chapter, which consisted of 4 dignities and 42 canons.[61] The canons had the right to wear the mitre on major solemnities. The dignities were: the Dean, the Provost, the Abbot of S. Petrus de Turre,[62] and the Abbot of S. Evodius.[63] The king of France and the Dauphin were honorary canons.[64]

The most distinguished member of the Chapter was perhaps the Bishop of Autun (1322–1331) Pierre Bertrandi, who had already been a canon when he was named cardinal-priest of San Clemente in 1331, by Pope John XXII.[65] He established the Collège d'Autun at the University of Paris in August 1337. He became Dean of the Chapter of Le Puy by appointment of Pope Benedict XII in 1340. In 1343, he added 15 bursaries to his establishment at the Collège d'Autun, for students in canon law, philosophy or theology from Clermont, Vienne, and Le Puy.[66]

The cathedral of Nôtre-Dame had a second college of canons (Chanoinie de Paupérie), ten in number,[67] founded by Charlemagne according to tradition and a charter no longer extant.[68] They had their own revenues and rents, which they did not share with the other Chapter. The Chanoines pauvres did not share in the right to elect a new bishop. The two chapters were frequently engaged in disputes with one another, usually over the right to exercise privileges.[69]

Other churches

[edit]The diocese of Le Puy had eight collegiate churches, that is, each was administered by a college of canons. Inside the city were: Saint-Pierre-le-Monastier, Saint-Pierre-de-la-Tour, Saint-Vosy, Saint-Georges-et-Saint-Agrève, and Saint-Jean-de-Jérusalem. Outside the city were: Saint-Paulien, Monistrol. and Retournac.[70] The diocesan seminary was located at S. Georges, and was staffed by priests from S. Sulpice in Paris.[71] Th

The Benedictine monastery of the Chaise Dieu,[72] around 40 km north-northwest of Le Puy, sacked by the Huguenots, was united in 1640 to the Benedictine Congregation of St-Maur. The congregation was dissolved in 1790, and the monks forced to leave. The church and monastery still stands, with the fortifications which Abbot André de Chanac (1378–1420) caused to be built. The abbey church, rebuilt in the fourteenth century by Pope Clement VI, who had made his studies there, and by Gregory XI, his nephew, contains the tomb of Clement VI.[73]

The church of S. Julien de Brioude, constructed in florid Byzantine style, dates from the eleventh or twelfth century.[74] In 1626, at the age of eighteen Jean-Jacques Olier, afterwards the founder of Saint-Sulpice, was Abbot in commendam of Pébrac,[75] and was an "honorary count-canon of the chapter of St. Julien de Brioude". These benefices were obtained for him by his ambitious father, Jacques Olier de Verneuil, formerly secretary and Master of Requests of King Henri IV, and a Conseiller d'Etat of Louis XIII.[76]

There was also the pilgrimage church of Notre-Dame de Pradelles, at Pradelles, a pilgrimage dating from 1512;[77] the chapel of Notre-Dame d'Auteyrac, at Sorlhac, which was very popular before the Revolution;[78] of Notre-Dame Trouvée, at Lavoute-Chilhac.[79]

Medieval visits

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Legend traces the origin of the pilgrimage of Le Puy to a 1st century or 3rd century apparition of the Virgin Mary, to a sick widow whom St. Martial had converted.

No French pilgrimage was more frequented in the Middle Ages, though it must be pointed out that a pilgrimage to Le Puy was sometimes imposed as a penance for sins, and sometimes as a punishment for a crime in an ecclesiastical court.[80] The church possessed one of the several Holy Prepuces (foreskin of Christ, removed at his bris).[81] The relic was said to grant fertility to women, and ease their complications in childbirth.[82] Charlemagne came twice, in 772 and 800; there is a legend that in 772 he established a foundation at the cathedral for ten poor canons (chanoines de paupérie), and he chose Le Puy, with Aachen and Saint-Gilles, as a centre for the collection of Peter's Pence.[further explanation needed]

Charles the Bald visited Le Puy in 877, Eudes of France in 892, Robert I of France in 1029, Philip Augustus in 1183. Louis IX met the King of Aragon there in 1245; and in 1254 passing through Le Puy on his return from Palestine, he gave to the cathedral an ebony image of the Blessed Virgin clothed in gold brocade. After him, Le Puy was visited by Philip the Bold in 1282, by Philip the Fair in 1285, by Charles VI of France in 1394, by Charles VII of France in 1420, and by the mother of Joan of Arc in 1429. Louis XI made the pilgrimage in 1436 and 1475, and in 1476 halted three leagues from the city and went to the cathedral barefooted. Charles VIII visited it in 1495, Francis I of France in 1533.

As an ex-voto for his deliverance, about 820 Bishop Theodulph, of Orléans brought to the Virgin Mary (Nôtre-Dame) of Le Puy, a magnificent Bible, the letters of which were made of plates of gold and silver, which he had himself put together while in prison at Angers.

St. Mayeul, St. Odilon, St. Robert, St. Hugh of Grenoble, St. Anthony of Padua, St. Dominic (in 1217),[83] St. Vincent Ferrer, St. John Francis Regis were pilgrims to Le Puy.

Pope Urban II arrived in Le Puy on 15 August 1095, and on that day, the Feast of the Assumption of the body of the Virgin Mary into heaven, he signed the Letters Apostolic convoking the Council of Clermont. On 18 August 1095, he dedicated the church of Ss. Vitalis & Agricola at the monastery of Casa Dei.[84] A canon of Le Puy, Raymond d'Aiguilles, chaplain to the Count of Toulouse, wrote a history of the crusade.

The Jubilee

[edit]Pope Gelasius II, Pope Callistus II, Pope Innocent II and Pope Alexander III visited Le Puy to pray, and with the visit of one of these popes must be connected the origin of the great Jubilee which is granted to Our Lady of Le Puy whenever Good Friday falls on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation. It is supposed that this jubilee was instituted by Callistus II, who passed through Le Puy, in April, 1119; or by Alexander III, who was there in August, 1162 and June 1165; or by Pope Clement IV, who had been Bishop of Le Puy. The first historically known jubilee took place in 1407, and in 1418 the chronicles mention a Bull of Pope Martin V prolonging the duration of the jubilee.[85] One such jubilee was granted by Pope Gregory XV. in an apostolic brief dated 23 December 1621.[86] Another occurred in 1796, and it was presided over by the Constitutional Bishop of Haute-Loire, Etienne Delcher.[87]

During the Middle Ages, everyone who had made the pilgrimage to Le Puy had the privilege of making a will in extremis with only two witnesses instead of seven.[citation needed]

The statue of the Virgin Mary of Le Puy and the other treasures escaped the pillage of the Middle Ages. The roving banditti were victoriously dispersed, in 1180, by the Confraternity of the Chaperons (Hooded Cloaks),[88] founded at the suggestion of a canon of Le Puy.

In 1793 the statue of the Virgin of Le Puy was torn from its shrine and burned in the public square.

Saints

[edit]Persons honored in the diocese as saints include:

- Calminius (Carmery), Duke of Auvergne, who prompted the foundation of the Abbey of Le Monastier, and Eudes, first abbot (end of the sixth century);

- Theofredus (Chaffre, Theofrid), Abbot of Le Monastier and martyr under the Saracens (c. 735);

- Mayeul, Abbot of Cluny,[89] who, in the second half of the tenth century, cured a blind man at the gates of Le Puy, and whose name was given, in the fourteenth century, to the university in which the clergy made their studies;

- Odilon, Abbot of Cluny (962–1049), who embraced the life of a regular canon in the monastery of Julien de Brioude;

- Robert de Turlande (d. 1067) who founded the monastery of Chaise Dieu in the Brioude district;

- Peter Chavanon (d. 1080), a canon regular, founder and first provost of the Abbey of Pébrac.

The Benedictine, Hughes Lanthenas (1634–1701),[90] the historian of the Abbey of Vendôme, who edited the works of Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Anselm, was a native of the diocese. The Benedictine, Jacques Boyer, joint author of Gallia Christiana was a native of the diocese of Le Puy. Cardinal Melchior de Polignac (d. 1741), son of Armand XVI, marquis de Polignac, Governor of Le Puy, was born at the Chateau de la Ronte; he was archbishop of Auch from 1725 to 1741, and author of the "Antilucretius".

Bishops

[edit]To 1000

[edit]- [Voisy 374][91]

- Suacre 396

- Scutarius (late IV/early V)[92]

- St Armentaire 451

- [St Benigne]

- St Faustinus ca. 468

- St Georg ca. 480

- St Marcellinus 6th century[93]

- Forbius ca. 550[94]

- Aurelius ca. 590[95]

- Agreve 602[96]

- [Eusebius ca. 615][97]

- Basilius ca. 635[98]

- Rutilius ca. 650

- Eudes ca. 670[99]

- Duicidius ca. 700[100]

- Higelricus ca. 720?[101]

- Torpio ca. 760?[102]

- Macaire ca. 780

- Borice 811

- Dructan ca. 850

- Hardouin 860, 866[103]

- Guido (I.) 875[104]

- Norbert de Poitiers 876–903[105]

- Adalard 919–924

- Hector 925?–934?

- Godescalc 935–955[106]

- Bégon 961

- Peter I. 970?

- Guido II of Anjou 975–993

- Stephan de Gévaudan 995–998

- Theotard 999

1000-1300

[edit]- Guido (III) 1000, 1004[107]

- Frédol D'Anduze (1016)[108]

- Stephan de Mercœur (1031–1052)

- Pierre (II) de Mercœur (1053–1073)[109]

- Stephan d'Auvergne (1073)

- Stephan de Polignac (1073–1077)

- Adhemar de Monteil (1082–1098)[110]

- Pons de Tournon (1102–1112)[111]

- Pons Maurice de Montboissier (1112–1128)[112]

- Humbert D'Albon (1128–1144)[113]

- Peter (III) (1145–1156)

- Pons (III) (1158)

- Pierre de Solignac (1159–1191)

- Aimard (1192–1195)

- Odilon de Mercœur (1197–1202)

- fr:Bertrand de Chalençon (1202–1213)[114]

- Robert de Mehun (1214–1219)

- Étienne de Chalencon (1220–1231)

- Bernard de Rochefort (1231–1236)

- Bernard de Montaigu (1236–1248)

- Guillaume de Murat (1248–1250)

- Bernard de Ventadour (1251–1256)[115]

- Armand de Polignac 1256–1257[116]

- Guy Foulques (1257–1260), later Pope Clement IV[117]

- Guillaume de La Roue 1260–1283[118]

- Frédol de Saint-Bonnet (1284–1289)[119]

- Guy de Neuville (1290–1296)[120]

- Jean de Comines (1296–1308)[121]

1300-1500

[edit]- Bernard de Castanet (1308–1317)

- Guillaume de Brosse (1317–1318)

- Durand de Saint Pourçain (1318–1326)[122]

- Pierre Gorgeul (1326–1327)[123]

- Bernard Brun (1327–1342)

- Jean de Chandorat (1342–1356)[124]

- Joannes Fabra (1356-1357)[125]

- Jean de Jourens (1357–1361)[126]

- Bertrand de la Tour 1361–1382

- Bertrand de Chanac (1382–1385) (Avignon Obedience) Administrator[127]

- Pierre Girard (1385–1390) (Avignon Obedience)[128]

- Gilles de Bellemère (1390–1392) (Avignon Obedience)[129]

- Itier de Martreuil (1392–1395) (Avignon Obedience)[130]

- Pierre d'Ailly (1395–1397) (Avignon Obedience)

- Elie de Lestrange (1397–1418) (Avignon Obedience)

- Guillaume de Chalencon (1418–1443)

- Jean de Bourbon (1443–1485)[131]

- Geoffroy de Pompadour (1486–1514)[132]

1500-1801

[edit]- Antoine de Chabannes (1514–1535)[133]

- Agostino Trivulzio administrator (1525)[134]

- François de Sarcus (1536–1557)

- Martin de Beaune (1557–1561)

- Antoine de Sénecterre (1561–1593)[135]

- Jacques de Serres (1596–1621)[136]

- Just de Serres (1621–1641)[137]

- Henri de Maupas du Tour (1643–1664)[138]

- Armand de Béthune (1665–1703)[139]

- Claude de La Roche-Aymon (1704–1720)[140]

- Godefroy Maurice de Conflans (1721–1725)[141]

- François-Charles de Beringhen D'Armainvilliers (1725–1742)[142]

- Jean-Georges Le Franc de Pompignan (1743–1774)[143]

- Joseph-Marie de Galard de Terraube (1774–1791) (1801)[144]

From 1823

[edit]- Louis-Jacques Maurice de Bonald (1823–1839)[145]

- Pierre-Marie-Joseph Darcimoles (1840–1846)[146]

- Joseph-Auguste-Victorin de Morlhon (1846–1862)

- Pierre-Marc Le Breton (1863–1886)

- André-Clément-Jean-Baptiste-Joseph-Marie Fulbert Petit (1887–1894)[147]

- Constant-Ludovic-Marie Guillois (1894–1907)

- Thomas François Boutry (1907–1925)

- Norbert Georges Pierre Rousseau (1925–1939)

- Joseph-Marie Martin (1940–1948)

- Joseph-Marie-Jean-Baptiste Chappe (1949–1960)

- Jean-Pierre-Georges Dozolme (1960–1978)

- Louis-Pierre-Joseph Cornet (1978–1987)

- Henri Marie Raoul Brincard, C.R.S.A (1988–2014)

- Luc Crépy (2015–2021)[148]

- Yves Baumgarten (2022–present)[149]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dave Whitson, Camino de Santiago - Via Podiensis: Le Puy to the Pyrenees on the GR65 (Kendal GB: Cicerone Press Limited, 2024).

- ^ Gallia christiana Vol. 2, p. 685.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 56.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 56-57: "Haec sunt nomina sanctorum confessorum qui construxerunt, domino permittente, domum beatae virginis Mariae: Evodius, Aurelius, Suacrus, Scutarius, et Erementarius, quorum festivitas caelebratur IIII id. novembr." Duchesne points out that the date is that of the feast of Saint George.

- ^ H. Fraisse, "Origines et motifs du Pouvoir temporel des évéques du Puy, au moyen-âge," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 1 (Le Puy: M.P Marchessou 1870–1871), pp. 529-554, at p. 534. Chassaing (ed.), Recueil des chroniqueurs du Puy-en-Velay: Le livre de Podio; ou chroniques d'Étienne Médicis bourgeois du Puy, pp. 82-83 (8 April 923) Schrör, p. 71.

- ^ Fraisse, pp. 534-535. "Cependant , dans tout ce qui fut accordé à l'évêque, nous ne voyons encore qu'un pouvoir seigneurial, ne lui donnant aucune juridiction directe sur les autres seigneurs du Velay, ne s'étendant point ni à leurs domaines, ni à leurs terres, ni à leurs sujets, ayant pour limites précises l'entier bourg adjacent à l'église...."

- ^ Fraisse, p. 543.

- ^ Philippus Jaffé & S. Loewenfeld, Regesta pontificum Romanorum, second edition (Leipzig: Veit 1885), p. 494.

- ^ Cabizolles, p. 199.

- ^ Léopold Delisle, Bibliotheque de l'École des Chartes, (in Latin and French) 37 (Paris 1876), pp. 109-110. Gallia christiana II, p. 697.

- ^ Léopold Delisle, Bibliotheque de l'École des Chartes, (in Latin and French) 37 (Paris 1876), pp. 109-111 (23 November 999).

- ^ Jaffé-Loewenfeld, Regesta pontificum Romanorum I, second ed., p. 541, no. 4265.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, "Instrumenta", p. 228: "ea si quidem conditione, ut sicut ecclesiae tuae privilegiis in suo statu manentibus, ordinatio episcoporum hujus sedis ad Romanum spectet."

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 698.

- ^ Schrör, pp. 71-72.

- ^ Jean Mabillon, Annales Ordinis S. Benedicti Occidentalium Monachorum Patriarchae, (in Latin), Tomus Quartus (Lucca: L. Venturini 1739), pp. 680-681. Schrör, p. 72.

- ^ Mabillon, p. 681.

- ^ The date is "VIII kal. Apr.," not VIII Apr. See: P. Jaffé-S. Lowewnfeld, Regesta Pontificum Romanorum, second ed. (Leipzig: Veit 1885), p. 720, no. 1616.

- ^ "quidquid parochialium speciali jure ad Aniciensem cognoscitur ecclesiam pertinere mansuro."

- ^ "...sancimus, ut tam tu quam tui deinceps successores nulli praeter Romanum, metropolitano subjecti sint, et omnes qui tibi in eadem sede successuri sunt per manum Romani pontificis, tanquam speciales Romanae sedis suffraganei consecreantur."

- ^ J.P. Migne (ed.), Patrologiae Latinae Tomus CLXIII (Paris 1856), pp. 155-156, no. cxlviii.

- ^ Em Roland, Les chanoines et les elections episcopales du XI au XIVe siècle (étude sur la restauration, l'évolution, la décadence du pouvoir capitulaire) (1080-1350), (in French and Latin), (Aurillac: Imprimerie moderne, 1909), p. 56.

- ^ Rocher, p. 445.

- ^ Régis Pontvianne, Recherches historiques sur l'Abbaye de Doue: et sur les prieurés qui en dépendaient (1162-1789), (in French), Vol. 1 (Le Puy: Impr. Catholique A. Prades-Freydier, 1900), pp. 20-21.

- ^ Pontvianne, pp. 30-31.

- ^ Augustin Chassaing, Cartulaire des Templiers du Puy-en-Velay, (in French and Latin), (Paris: Champion 1882), p. vi.

- ^ Chassaing, pp. xxv-xxix.

- ^ Chassaing, p. xxix.

- ^ Diocèse du Puy-en-Velay, "Quelques dates;" retrieved 18 September 2024. A. Chassaing, Le livre de Podio, ou Chroniques d'Étienne Médicis, (in French), Volume 2 (Le Puy-en-Velay 1869), pp. 188-189.

- ^ Léopold de Chérancé, Saint Antoine de Padoue, (in French) (Librairie Ch. Poussielgue, 1895), pp. 60-63.

- ^ Charles Rocher (1873). Les rapports de l'église du Puy avec la ville de Girone en Espagne et le comté de Bigorre (in French). Le Puy: Bérard. p. 60.: "La tradition vellave rapporte que le premier évèque de Girone fut Pierre, chanoine du Puy (1).... Cette tradition était religieusement conservée par le Chapitre Notre-Dame," citing a report on the Jubilee of 1701 by Canon Pierre Rome.

- ^ François Bochart de Saron de Champigny, Histoire de l'église angélique de Nôtre-Dame du Puy, (in French), (Le Puy: Chez Antoine Delagarde, 1693), pp. 134-135.

- ^ Charles Rocher (1873). Les rapports de l'église du Puy avec la ville de Girone en Espagne et le comité de Bigorre (in French). Le Puy: Bérard.

- ^ Jules Coulet, Étude sur l'Office de Girone en l'honneur de Saint Charlemagne, (in French), (Montpellier: Coulet et fils, 1907), pp. 91-96.

- ^ Cubizolles, p. 229-230.

- ^ Jules Thomas, Le Concordat de 1516: Deuxième partie. Les documents concordataires, (in French and Latin), (Paris: A. Picard, 1910), pp. 60–65. The right had to be exercised by the king within six months of the occurrence of the vacancy of a benefice.

- ^ Cubizolles, pp. 265-270.

- ^ Cubizolles, p. 280.

- ^ Cubizolles, pp. 284-285. Diocèse du Puy-en-Velay, "Quelques dates;" retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ "X.", "Une visite pastorale au dix-septième siècle," in: Tablettes historiques du Velay Vol. 2 (Le Puy 1872), p. 45.

- ^ "X.", "Une visite pastorale au dix-septième siècle," in: Tablettes historiques du Velay Vol. 2 (Le Puy 1872), p. 79.

- ^ Jean-Arnaud-Michel Arnaud, Histoire de Velay jusqu'à la fin du régime de Louis XV, (in French), Vol. 2 (Le Puy: J. B. La Combe, 1816) p. 238.

- ^ Etienne Michel Faillon, Vie de M. Olier fondateur du séminaire de S. Sulpice, (in French), Vol. 2 (Paris: Poussielgue-Rusand, 1841), pp. 375-379.

- ^ Jean, p. 104.

- ^ Pierre Brizon, L'église et la révolution française des Cahiers de 1789 au Concordat, (in French), (Paris: Pages libres, 1904), p. 27. François-Alphonse Aulard, Christianity and the French Revolution, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1927), p. 54.

- ^ Pisani, pp. 10-11. Departement de Puy-de-Dôme, "Création du département"; retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Civil Constitution," Title I, "Article 1. Chaque département formera un seul diocèse, et chaque diocèse aura la même étendue et les mêmes limites que le département."

- ^ Ludovic Sciout, Histoire de la constitution civile du clergé (1790-1801): L'église et l'Assemblée constituante, (in French and Latin) ., Vol. 1 (Paris: Firmin Didot 1872), p. 182: Art. 2 "...Tous les autres évêchés existant dans les quatre-vingt-trois départements du royaume, et qui ne sont pas nommément compris au présent article, sont et demeurent supprimés."

- ^ Pisani, pp. 10-12. Jean-de-Dieu-Raimond de Boisgelin de Cucé, Exposition des principes sur la Constitution civile du clergé, par les évêques députés á l'Assemblée nationale, (in French), (Paris: Chez Guerbaert, 1791), p. 11: "C'est une maxime incontestable, que toute jurisdiction ne peut cesser, que par la puissance qui la donne. C'est de l'église seule, que les évêques tiennent leur jurisdiction; c'est l'église seule, qui peut les en priver."

- ^ Pisani, p. 296.

- ^ Pisani, p. 298.

- ^ Pisani, p. 299.

- ^ J.B. Duvergier (ed.), Collection complète des lois, décrets, ordonnances, réglemens et avis du Conseil d'état, (in French and Latin), Volume 13 (Paris: A. Guyot et Scribe, 1826), pp. 371-372; p. 387.

- ^ Ritzler and Sefrin VI, p. 85, note 1.

- ^ Ritzler & Sefrin VI, p. 85, note 1. Bullarii Romani continuatio, (in Latin), Tomus septimus, pars 2 (Prati: Typographua Aldina 1852), pp. 1512-1517.

- ^ Bullarii Romani continuatio, (in Latin), Tomus septimus, pars 2 (Prati: Typographua Aldina 1852), pp. 2295-2304.

- ^ "Paternae Charitatis", § 4.

- ^ Charles-François Druon. Le Concile du Puy, tenu en octobre 1873: simples notes, (in French) (Paris: Librairie de Victor Palmé, 1875), p. iii.

- ^ Francisque Mandet, Histoire du Velay: Monuments historiques de la Haute-Loire et du Velay: archéologie, histoire, (in French), Vol. 6 (Le Puy: M.-P. Marchessou 1862), pp. 175-193.

- ^ Xavier Barral i Altet, La cathédrale du Puy-en-Velay, (in French), (Seuil, [Milan], [Paris]: Skira, 2000).

- ^ Ritzler & Sefrin VI, p. 85, note 1.

- ^ The abbey of S. Petrus de Turre was in existence by 890. Its abbot was a dignitary in the cathedral Chapter, second only to the Provost. Gallia christiana II, pp. 752-755.

- ^ The abbey of S. Evodius was in existence by 988. It was converted into a collegiate church of twelve canons and the abbot; the abbot was also a dignity of the cathedral, but did not hold a canonate. Gallia christiana II, pp. 757-758.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 686.

- ^ Eubel I, p. 16, no. 28; 73.

- ^ Ch. Rocher, "La Baronnie de Saint Germain Laprade," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 1 (Le Puy: M.P Marchessou 1870–1871), pp. 370-371.

- ^ Abbé Payrard, "Chanoines pauvres de N.-D. du Puy," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 1 (1871), pp. 14-22; 70-75; 97-102; 247-259; 385-394.

- ^ The charter was copied and published. Payrard, pp. 18-21.

- ^ Payrard, pp. 70-71; pp. 99-102. The loss of a lawsuit by the Chanoines pauvres against the Chapter was announced on 14 July 1740: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 8 (1878), p. 183.

- ^ Jean, p. 105.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 686.

- ^ Paul Georges, L'abbaye bénédictine de La Chaise-Dieu: recherches historiques et héraldiques, (in French) (Paris: Champion, 1924).

- ^ Abbé Bonnefoy, L'abbaye de Saint-Robert de la Chaise-Dieu: guide du touriste, (in French), 3rd edition, Aurillac: Impr. Moderne, 1903, pp. 35-40.

- ^ Pierre Cubizolles, Le noble Chapitre Saint-Julien de Brioude, (in French) Aurillac 1980.

- ^ Pébrac, in the diocese of Saint-Flour, is about 44 km west of Le Puy by road. In 1636, Ollier gave a retreat for the clergy of the diocese of Saint-Flour at his monastery of Pébrac, paying all the expenses himself Thompson, p. 70.

- ^ Edward Healy Thompson, The Life of Jean-Jacques Olier: Founder of the Seminary of St. Sulpice (Burns & Oates, 1886), pp. 3, 11.

- ^ Pierre Geyman, Histoire de l'Image miraculeuse de Notre-Dame de Pradelles, (in French), (Le Puy: J.-B. Gaudelet, 1843).

- ^ Auguste Fayard, Notre-Dame d'Auteyrac: lieu saint entre Auvergne et Velay. (in French), Aurillac: Impr. moderne, 1969.

- ^ Régis Pontvianne, Notre-Dame-Trouvée de la Voûte-Chilhac d'après les archives du monastère et de la paroisse (1496-1913), (in French), (Le Puy: l'Avenir de la Haute-Loire, 1913).

- ^ Ch. Rocher, "Le Pèlerinage du Puy," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 1 (Le Puy: M.P Marchessou 1870–1871), pp. 475-478.

- ^ Robert P. Palazzo, "Holy Foreskin," in: Michael Kimmel, Christine Milrod, Amanda Kennedy (edd.), Cultural Encyclopedia of the Penis, (London-New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), pp. 85-87.

- ^ Odo de Gissey, Discours historiques de la tres-ancienne deuotion de Nostre Dame du Puy, (in French), Second edition (François Varoles, 1644), pp. 56-63.

- ^ Augusta Theodosia Drane, The History of St. Dominic, Founder of the Friars Preachers (Longmans, Green and Company, 1891), p. 189.

- ^ P. Jaffé & S. Loewenfeld, Regesta pontificum Romanorum, (in Latin), Vol. 1, second ed. (Leipzig: Veit 1885), p. 680, nos. 5570-5572.

- ^ Cubizolles, pp. 243-259, at p. 259: "Les principaux jubilés qui ont eu lieu jusqu'à présent sont ceux des années: 1407, 1418, 1429, 1440, dont il a été question, 1502, 1513, 1524, 1582, 1622, 1633, 1644, 1701, 1712, 1751, 1785, 1796, 1842, 1853, 1864, 1910, 1921, 1932."

- ^ "X.", "Une visite pastorale au dix-septième siècle," in: Tablettes historiques du Velay Vol. 2 (Le Puy 1872), p. 44.

- ^ Pisani, p. 297.

- ^ Mandet, pp. 193-194

- ^ Paul Guérin. Les petits bollandistes: vies des saints de l'Ancien et du Nouveau Testament..., (in French), (Paris: Bloud et Barral, 1888), pp. 460-466 .

- ^ Marie-Louise Auger, "La Bibliothèque de Saint-Bénigne de Dijon au XVIIe siècle: Le témoignage de Dom Hughes Lanthenas," in: Scriptorium 39 (1985), pp. 234-264.

- ^ Voisy is identified with a bishop named Evodius (Duchesne, pp. 56. 57.) This Evodius is then identified with the bishop Euodius or Euuodius who was present at the Council of Valence in 374. C. Munier, Concilia Galliae (Turnholt: Brepols 1963), p. 41). The name of Euodius' diocese, however, is not given. Others identify him with a monk of the end of the 7th century. Voisy is credited by local tradition with the definitive transfer of the episcopal seat to Le Puy.

- ^ Scutarius: Duchesne, p. 57.

- ^ Bishop Norbertus transferred Marcellinus' remains from the church of S. Paulinus to Menistrolium, on the same day as he transferred the remains of S. George to Podium (Velay) to the church of S. George. Andrea Du Saussay, Martyrologivm Gallicanvm ...: Martyrologii Gallicani Pars Posterior Trimestris, Octobrem, Novembrem Et Decembrem Complectens, (in Latin), (Paris: Sebstian Cramoisy, 1637), p. 1027.

- ^ Forbius: Cubizolles, p. 42.

- ^ Aurelius is mentioned by Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum Book X, chapter 25. Duchesne, p. 57, no. 2. Cubizolles, p. 42.

- ^ Agreve: Cubizolles, p. 42.

- ^ Eusebius: Cubizolles, p. 43: "...l'épiscopat vellave d'Eusèbe est plus que douteux, tout au mons à cette époque.".

- ^ Bishop Basilius is said to have constructed a shrine at the tomb of S. Theofrid. His actions, however, are the inventions of later authors. Gallia christiana II, p. 692. Cubizolles, p. 43.

- ^ Eudes: Cubizolles, p. 44.

- ^ Dulcidius, known from the "Acts of S. Agripanus," is said to have built the basilica of S. Agrève, which became a collegiate church. Cubizolles, p. 44.

- ^ Higelricus: Gallia christiana II, p. 692. Cubizolles, p. 44.

- ^ Torpio: Gallia christiana II, p. 691. Cubizolles, p. 44.

- ^ Bishop Harduinus was present at the council of Thusey in 860, and the council of Soissons in 866. Jacques Sirmond, Concilia antiqua Galliae tres in tomos ordine digesta, (in Latin), Volume 3 (Paris: Sebastiani Cramoisy, 1629), p. 163: "Arduinus Vellaunensium Episcopus subscripsi." Duchesne, p. 58, no. 4.

- ^ Bishop Guy signed the privilege of Tournus in 875. He attended the concilium Pontigonense (Ponthion) in 876. He died on 24 July. Jacques Sirmond, Concilia antiqua Galliae tres in tomos ordine digesta, (in Latin), Volume 3 (Paris: Sebastiani Cramoisy, 1629), p. 443: "Vvido Vellauensis Ecclesiæ Episcopus subscripsi." Duchesne, p. 58, no. 5.

- ^ Norbert was the son of Bernard, Count of Auvergne, Chalons, and Mâcon. He is said to have brought the remains of St. George from S. Pauliani to Anicium (Le Puy). The story was written down by Bishop Guillaume de Chalancon in 1428. Gallia christiana II, pp. 693-694.

- ^ Godescalc: Nancy Marie Brown, The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages (New York: Basic Books, 2010), pp. 19-20, 22. Charles Rocher (1873). Les rapports de l'église du Puy avec la ville de Girone en Espagne et le comté de Bigorre (in French). Le Puy: Bérard. pp. 69–72., proposing different dates, 934–972.

- ^ In 1000 (or 1002), Bishop Guido of Le Puy was present at a meeting of more than nine bishops, along with civil rulers and members of the nobility, to frame canons on social behavior. He acted as the amanuensis, and obtained the confirmation of the archbishop of Bourges and the archbishop of Vienne. Gallia Christiana II, p. 698. J.D. Mansi (ed.), Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, editio novissima, (in Latin) Vol 19 (Venice: A. Zatta 1774), p. 271. Georges Molinié, L'organisation judiciaire, militaire et financière des associations de la paix: étude sur la paix et la Trêve de Dieu dans le midi et le centre de la France, (in French), (Toulouse: Marqueste, 1912), p. 23.

- ^ Frédol: Albert Boudon-Lashermes, Le vieux Puy: Le grand pardon de Notre-Dame et l'èglise du Puy de 992 à 1921, (in French), (Le Puy: Badiou-Amant, 1921), p. 22.

- ^ Bishop Pierre went on pilgrimage to Compostella, and in 1063 participated in the consecration of the basilica of S. John in Laon. Charles Rocher (1873). Les rapports de l'église du Puy avec la ville de Girone en Espagne et le comté de Bigorre (in French). Le Puy: Bérard. p. 13.

- ^ Ch. Rocher, "Note sur Adhémar de Monteil," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques de la Haute-Loire Vol. 1 (Le Puy: M.P Marchessou 1870–1871), pp. 395-408.

- ^ Bishop Pons de Tournon died on 24 January 1112. Jean B. Courcelles, Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France, des grands dignitaires de la couronne, des principales familles nobles du royoume, et des maisons princières de l'Europe: préc ́dé de la généalogie de la maison de France, (in French), Volume 10 (Paris: Bertrand, 1829), "De Montboissier," p. 7.

- ^ Pons Maurice had been abbot of Chaise-Dieu since at least 1105. He died on 20 April 1128. Courcelles, p. 7. Lambert comte de Résie, Histoire de l'Église d'Auvergne, (in French), Volume 3 (Clermont Ferrand: Librairie Catholique, 1885), pp. 100-101.

- ^ Charles Rocher, Humbert d'Albon, évêque du Puy, 1127-1144, (in French), (Le Puy: Marchessou fils, 1880), passim.

- ^ Bertrand died on 21 December 1213. Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 91.

- ^ Bernard had been archdeacon of Limoges. He was already elected and confirmed by Pope Innocent IV, when, on 19 May 1254, the pope granted the bishop-elect permission to delay his consecration. At the same time, the bishop-elect was allowed to use the mitre and ring, and to impart solemn blessings. He resigned the diocese in Spring 1256, without having been consecrated. Élie Berger, Les registres d'Innocent IV, (in Latin), Vol. 3 (Paris: Fontemoing 1897), p. 411, no. 7500. Eubel I, p. 91, with notes 3, 4 and 5.

- ^ In Spring 1256, Bishop-elect Bernard de Ventadour submitted his resignation to Pope Alexander IV, through four procurators, three canons of Puy and the archpriest of S. Paulianus. At their request, on 14 May 1256 the pope provided (appointed) Armandus de Polignac, Provost of the cathedral Chapter of Le Puy, as the new bishop. He died in May 1257. Charles Bourel de la Roncière, Les registres d'Alexandre IV (Paris: Thorin 1895), p. 398, no. 1335. Eubel I, p. 91 with note 6.

- ^ Folques was elected unanimously by the cathedral Chapter. When his request for confirmation was submitted to Pope Alexander IV, defects were found in the process of election, and the election was voided ("Examinato igitur ipsius electionis processu, eam ex certis causis non duximus confirmandam"). The pope then provided (appointed) Guido to the office of bishop of Le Puy. He was named archbishop of Narbonne on 10 October 1259. Guy Fulcoldi was elected pope on 5 February 1265. Eubel I, pp. 8; 91 with note 7; 356. C. Bourel de la Roncière, Les registres d'Alexandre IV (in Latin), (Paris: Thorin 1895), pp. 696-697, no. 2261.

- ^ Guillaume de la Roda was elected bishop on or about 22 July 1260. He was approved by Pope Urban IV on 21 December 1263. The pallium was not conferred on him until 19 August 1267. He died on 9 or 10 August 1283, and his Will was probateed on 19 August 1263. Gallia christiana II, "Instrumenta," p. 236. Eubel I, p. 91 with note 9.

- ^ King Philip III of France arrived in Le Puy on 23 October 1263. On the Tuesday before All Saints' Day, Petrus de Stagno, Archdeacon of Rodez, was elected by the Chapter, through the canonical "way of compromise." He refused the election. The Chapter returned to its deliberations, but were unable to reach agreement when the canonical limit of six months ran out ("praefati ccapitulum, post diversos tractatus super hiis inter se habitos, attendentes quod de tempore ad eligendum eis de jure concesso, modicum supererat...."); they sent representatives and documents to the pope, asking him to provide a bishop for them. Pope Martin IV finally appointed Fredolus, Bishop of Oviedo, on 10 June 1284. He died on 8 October 1289. Gallia christiana II, p. 719, and "Instrumenta," p. 237. François Olivier-Martin, Les Registres de Martin IV (in Latin), (Paris: Fontemoing 1901), pp. 241-242, no. 505. Eubel I, pp. 91, 382.

- ^ When Bishop Fredolus died, on 8 October 1289, the electors of Le Puy appointed a commission of four compromissors, who chose Andrea, the archdeacon of Redensis in the Church of Narbonne. Andre declined the election. Pope Nicholas IV then, on 20 June 1290, appointed Guy, one of his chaplains who was an Auditor Litterarum Contradictarum (judge). Bishop Guy was transferred to the diocese of Saintes by Pope Boniface VIII on 24 April 1296. He died c. 1312. Ernest Langlois, Les regestes de Nicolas IV (in Latin), (Paris: Fontemoing 1905), p. 459, no. 2750. Eubel I, pp. 91, 537.

- ^ Jean had been abbot of S. Germain-des-Pres in Paris, but was a member of the papal court. He was provided (appointed) by Pope Boniface VIII on 15 May 1296. He was consecrated a bishop by Cardinal Hugues Seguin, O.P, Bishop of Ostia, and immediately invested with the pallium. He died in 1308. Antoine Thomas, Maurice Faucon & Georges Digard, Registres de Boniface VIII (in Latin), (Paris: E. de Boccard 1907), p. 376, no. 1071. Eubel I, p. 91 with note 11.

- ^ Durand had been the first bishop of the new diocese of Limoux, when he was transferred to Le Puy by Pope John XXII on 14 February 1318, replacing Guillaume de Brosse, who had been transferred to the diocese of Meaux. Durand was himself transferred to Meaux on 13 March 1326. He died on 10 September 1334. Gallia christiana II, p. 723. Eubel I, pp. 91; 306 with note 1; 334.

- ^ Pierre had been Dean of the cathedral and then Bishop of Le Mans (1312–1326). He was transferred to the diocese of Le Puy by Pope John XXII on 13 March 1326. He died early in 1327, before 10 February. Gallia christiana II, p. 723-724. Eubel I, pp. 91, 181.

- ^ A native of Le Puy, Jean held a doctorate in civil and canon laws. He had been abbot of Casa-Dei, and Auditor of the Sacred Palace (judge in the papal court). He was appointed bishop of Le Puy by Pope Clement VI on 25 September 1342. He died on 15 September 1356, in his castle at Monistrol; he was buried at Casa-Dei in the church of S. Maria de collegio, which he had had constructed. Gallia christiana II, p. 725. Eubel I, p. 91.

- ^ Joannes Fabra had been abbot of the monastery of Grandimont. He was appointed bishop of Le Puy by Pope Innocent VI on 12 October 1356. He was then transferred to the diocese of Tortosa (Spain) on 27 (or 25) February 1357, and then to the diocese of Carcasonne in January 1362. Gallia christiana II, p. 726, note (b). Eubel I, pp. 91, 223.

- ^ Jean obtained his doctorate in laws from the University of Toulouse on 1 October 1329, and then taught law. He was appointed bishop of Riez on 14 August 1348. On 10 August 1350, he was named Auditor causarum contradictarum (judge on appeal) in the papal curia. He was appointed bishop of Valence on 2 March 1352. On 5 May 1354, he was transferred to the diocese of Luçon. He was transferred to the diocese of Le Puy on 27 (or 25) February 1357. On 5 March 1362, he was appointed Auditor Sacri Palatii in the papal curia. He died in 1361. Gallia christiana II, p. 725-726. Eubel I, pp. 91, 315, 417, 513.

- ^ Bertrand was Archbishop of Bourges and Patriarch of Jerusalem. He was appointed administrator of the diocese of Le Puy by Pope Clement VII of the Avignon Obedience. He was named a cardinal on 12 July 1385, and superseded on 17 July 1385. Gallia christiana II, p. 729. Eubel I, pp. 28 no. 20; 91; 276.

- ^ Girardi held a licenciate in law, and was Provost of Marseille as well as a papal chamberlain. He was appointed bishop of Lodève on 17 October 1382. He was transferred to the diocese of Le Puy on 17 July 1385, and in 1386 was a special nuncio to bring the cardinal's red hat to Pileo da Prata and Galeazzo da Petramala. On 15 November 1388, he was present in Avignon when Cardinal Pierre de Cros made his Will. He was named a cardinal by Pope Clement VII on 17 October 1390. Gallia christiana II, p. 729. Eubel I, pp. 28 no. 32; 91; 310 with note 8.

- ^ Gilles (Aegidius) de Bellemere: Gallia christiana II, p. 730. Eubel I, p. 91.

- ^ Itier de Martreuil held the degree of doctor of Canon Law. He had been Cantor in the cathedral Chapter of Poitiers, and Provost of the collegiate church of S. Audomar (diocese of Terouane). He was appointed bishop of Le Puy by Pope Clement VII on 19 August 1392. He was transferred to the diocese of Poitiers on 2 April 1395 by Pope Benedict XIII. He died in 1403. Gallia christiana II, p. 730. Eubel I, pp. 91, 399.

- ^ Bishop Jean de Bourbon, Abbot of Cluny and royal governor of Languedoc, rebuilt the episcopal palace. He died on 2 December 1485. Chassaing (ed.), Recueil des chroniqueurs du Puy-en-Velay: Le livre de Podio; ou chroniques d'Étienne Médicis bourgeois du Puy, p. 133. Eubel, Hierarchia catholica II, p. 89 with note 1.

- ^ Pompadour was confirmed on 15 March 1486. He died on 8 May 1514. Eubel, Hierarchia catholica II, p. 89 with note 2; III, p. 110, note 2.

- ^ Antoine de Chabannes had been a canon of Le Puy. He was elected by the Chapter on 12 July 1514, and made his entry into the city from his consecration in Rome on 10 November 1516. He had obtained a Jubilee from Pope Leo X for the Feast of S. Martin (10–11 November). Chassaing (ed.), Recueil des chroniqueurs du Puy-en-Velay: Le livre de Podio; ou chroniques d'Étienne Médicis bourgeois du Puy, p. 136. Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 110.

- ^ Cardinal Trivulzio was apostolic administrator from 15 September to 18 August 1525. Eubel I, p. 110.

- ^ Antonius was abbot of S. Theofredus (diocese of Le Puy), a position he continued to hold as bishop. He was confirmed in consistory on 27 June 1561. Eubel III, p. 110 with note 8.

- ^ Jacques De Serres was approved by Pope Clement VIII on 18 August 1597. He died on 28 January 1621. Tablettes historiques II (1871), p. 244. Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 85 with note 2. Bergin, pp. 129-130; 701.

- ^ Jacobus de Serres, nephew of Bishop Jacques de Serres, was named bishop of Titopolis on the nomnation of King Louis XIII on 11 April 1616, and appointed coadjutor bishop with rights of succession. He succeeded as Bishop of Le Puy in 1621. He died in August 1641. Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 85 with note 3. Bergin, pp. 129-131; 701-702.

- ^ Maupas had been grand almoner to Queen Anne of Austria (1634–1641). He was nominated by King Louis XIII on 30 August 1641, but not approved by Pope Urban VIII until the consistory of 22 June 1643. In the meantime, both Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII, who had been on campaign in Savoy, had died. Maupas was transferred to the diocese of Evreux on 31 March 1664, by Pope Alexander VII. He died on 12 August 1680. Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, pp. 85 with note ; 180 with note 7. Bergin, pp. 131, 279, 668-669.

- ^ Armand de Béthune, canon of Bordeaux, was nominated bishop of Le Puy by King Louis XIV on 19 August 1661, and approved by Pope Alexander VII on 22 April 1665. He died on 10 December 1703. Jean, pp. 102-103. Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 85 with note 5.

- ^ La Roche-Aymon was the second son of Count Antoine de La Roche-Aymon. He held a doctorate in theology, and was archdeacon, canon and vicar-general of the diocese of Mende. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy by King Louis XIV on 24 December 1703, and approved by Pope Clement XI on 28 April 1704. His consecration as a bishop took place at the Seminary of S. Sulpice in Paris on 22 June 1704. He died in July 1720. Jean, p. 103. Ritzler & Sefrin, Hierarchia catholica V, p. 83 with note 2.

- ^ Conflans: Jean, p. 103. Ritzler & Sefrin, Hierarchia catholica V, p. 83 with note 3.

- ^ Beringhen was born in Paris in 1692, son of the Comte de Chateauneuf, premier écuyer of the kin. He was a doctor of theology, and was provost of the collegiate church of Pignans, diocese of Fréjus. He served as archdeacon of Melun (diocese of Sens), and vicar-general of Archbishop Chavigny of Sens. He represented Sens at the general assembly of the clergy of France in 1723. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy on 31 March 1725 by King Louis XV, and confirmed on 20 February 1726 by Pope Benedict XIII. He died in Le Puy on 17 October 1742, at the age of 51. Jean, p. 103-104. Ritzler & Sefrin, Hierarchia catholica V, p. 83 with note 4.

- ^ Born in Montauban, Le Franc held a doctorate in theology (Paris), and was a socius of the Sorbonne. He served as archdeacon and vicar-general of Montauban. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy by King Louis XV on 17 December 1742, and approved in consistory by Pope Benedict XIV on 15 July 1743. He was consecrated a bishop on 11 August 1743. He resigned the diocese of Le Puy on 14 April 1774, having been nominated archbishop of Vienne by the king on30 January 1774. His nomination was approved by Pope Clement XIV on 9 May 1774. He resigned the diocese of Vienne on 14 December 1789, and died in Paris on 29 or 30 December 1790, at the age of 76. Jean, p. 477. Ritzler & Sefrin Hierarchia catholica VI, pp. 85 with note 2; 441 with note 5.

- ^ The son of Gilles, Marquis de Terraube, Joseph-Marie had been Prior of the Sorbonne, and almoner of the king. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy in February 1774, and approved in consistory by Pope Clement XIV on 6 June 1774. He was consecrated in Paris on 24 July 1774 by Archbishop Jean-Georges Lefranc de Pompignan of Vienne. With the French Revolution, in 1791 he fled to Savoy, refusing the oath to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. When Pope Pius VII asked for the resignations of all the bishops of France, Galard de Terraube refused. His diocese was suppressed on 29 November 1801. He died in Ratisbon on 8 October 1804. Jean, p. 104. Ritzler & Sefrin Hierarchia catholica VI, p. 85 with note 3.

- ^ In 1811, De Bonald was appointed a cleric of the imperial chapel. In 1816, De Bonald was secretary of the extraordinary mission sent to Pius VII by the restored French monarchy. In 1817, De Bonald was appointed grand-vicar and archdeacon of Chartres. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy by King Louis XVIII on 12 February 1823, and approved by Pope Pius VII on 10 March 1823. He was nominated Archbishop of Lyon by King Louis Philippe on 11 December 1839, and approved by Pope Gregory XVI on 27 April 1840. He was appointed a cardinal on 1 March 1841. J.B. Blanchon, Le Cardinal de Bonald, archevêque de Lyon. Sa vie et ses œuvres, (in French), Lyon: Bauchu 1870), pp. 5-12. Ritzler & Sefrin, Hierarchia catholica VII, pp. 77, 246.

- ^ Born in Rueyre (Lot) in 1801, Darcimoles had been a canon and vicar general of Sens. He was nominated bishop of Le Puy by King Louis Philippe on 4 June 1840, and preconised (appointed) by Pope Gregory XVI on 13 July 1840. He was later Archbishop of Aix, from 12 April 1847. A. Pascal, "Le clergé du diocèse d'Aix," in: Annales de la Société d'Études provençales, Volume 21 (Aix-en-Provence 1924), pp. 40-41. Ritzler & Sefrin, Hierarchia catholica VII, p. 77; VIII, p. 113.

- ^ (later Archbishop of Besançon)

- ^ Bishop Luc (Lucien) Crepy (in French) was appointed by Pope Francis on 12 February 2015. >On 6 February 2021, Bishop Crepy was transferred to the diocese of Versailles. Église en Yvelines (Departement d' Yvelines), Diocèse de Versailles, "Mgr Luc Crepy, évêque du diocèse de Versailles. Biographie;" (in French); retrieved: 18 September 2024

- ^ "Resignations and Appointments, 16.02.2022" (Press release). Holy See Press Office. 16 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.. Diocèse du Puy-en-Velay, "Monseigneur Yves Baumgarten;" (in French); retrieved: 18 September 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Gams, Pius Bonifatius (1873). Series episcoporum Ecclesiae catholicae: quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro apostolo. Ratisbon: Typis et Sumptibus Georgii Josephi Manz. pp. 548–549. (Use with caution; obsolete)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1913). Hierarchia catholica (in Latin). Vol. 1 (Tomus I) (second ed.). Munster: Libreria Regensbergiana. p. 527.

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1914). Hierarchia catholica (in Latin). Vol. 2 (Tomus II) (second ed.). Munster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1923). Hierarchia catholica (in Latin). Vol. 3 (Tomus III) (second ed.). Munster: Libreria Regensbergiana.. Archived.

- Gauchat, Patritius (Patrice) (1935). Hierarchia catholica (in Latin). Vol. 4 (IV) (1592-1667). Münster: Libraria Regensbergiana. Retrieved 2016-07-06. p. 219.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1952). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi (in Latin). Vol. 5 (V) (1667-1730). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1958). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi. Vol. 6 (Tomus VI) (1730–1799). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1968). Hierarchia Catholica medii et recentioris aevi (in Latin). Vol. VII (1800–1846). Monasterii: Libreria Regensburgiana.

- Remigius Ritzler; Pirminus Sefrin (1978). Hierarchia catholica Medii et recentioris aevi (in Latin). Vol. VIII (1846–1903). Il Messaggero di S. Antonio.

- Pięta, Zenon (2002). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentioris aevi (in Latin). Vol. IX (1903–1922). Padua: Messagero di San Antonio. ISBN 978-88-250-1000-8.

Studies

[edit]- Bayon-Tollet, Jacqueline (1982). Le Puy-en-Velay et la révolution française, 1789-1799. (in French). (Le Puy: Université de Saint-Etienne, 1982.

- Bergin, Joseph (1996). The Making of the French Episcopate, 1589-1661. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06751-4.

- Boudon-Lashermes, Albert (1912). L'instruction publique au Puy sous l'Ancien Régime. (in French). Saint-Etienne: Theolier & Thomas 1912.

- Chassaing, Augustin (ed.) (1869). Recueil des chroniqueurs du Puy-en-Velay: Le livre de Podio; ou chroniques d'Étienne Médicis bourgeois du Puy. (in French and Latin). Le Puy-en-Velay: Marchessov, 1869.

- Cubizolles, Pierre (2005). Le diocèse du Puy-en-Velay des origines à nos jours. (in French). Saint-Just-près-Brioude: Editions Créer, 2005.

- Duchesne, Louis (1910). Fastes épiscopaux de l'ancienne Gaule: II. L'Aquitaine et les Lyonnaises. Paris: Fontemoing.. Archived.

- Du Tems, Hugues (1775). Le clergé de France (in French). Vol. 3 Paris: Bruney 1775.

- Jean, Armand (1891). Les évêques et les archevêques de France depuis 1682 jusqu'à 1801 (in French). Paris: A. Picard. pp. 102–105.

- Lascombe, Adrien (1882). Répertoire général des hommages de l'évêché du Puy, 1154-1741. (in French and Latin).Bérard-Rousset, 1882.

- Mandet, Francisque (1860). Nôtre-Dame du Puy: légende, archéologie, histoire. (in French). Le Puy: M.-P. Marchessou, 1860.

- Pisani, Paul (1907). Répertoire biographique de l'épiscopat constitutionnel (1791-1802) (in French). Paris: A. Picard et fils.

- Rocher, Charles (1874). "Pouillé du diocèse du Puy," (in French), in: Tablettes historiques du Velay Vol. 4 (Le Puy: Th. Bérard 1874), pp. 444-498; 508-532.

- Sainte-Marthe, Denis (1720). P. Paolin (ed.). Gallia Christiana, In Provincias Ecclesiasticas Distributa. (in Latin). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia, 1720. [pp. 685-740; "Instrumenta", pp. 222-262].

- Schrör, Matthias, "Von der kirchlichen Peripherie zur römischen Zentrale? um Phänomen der Bistumsexemtion im Hochmittelalter anhand der Beispiele von Le Puy-en-Velay undd Bamberg," (in German), in: Jochen Johrendt, Harald Müller, Rom und die Regionen: Studien zur Homogenisierung der lateinischen Kirche im Hochmittelalter (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2012), pp. 63-82.

External links

[edit]- (in French) Centre national des Archives de l'Église de France, L’Épiscopat francais depuis 1919, retrieved: 2016-12-24.