Ballpoint pen

A retractable ballpoint pen assemblage (Schneider K15) | |

| Type | Pen |

|---|---|

| Inventor | John J. Loud (original) László Bíró (modern) |

| Inception | 1888 (original) 1938 (modern) |

| Manufacturer | Bic and others |

A ballpoint pen, also known as a biro[1] (British English), ball pen (Hong Kong, Indian, Indonesian, Pakistani, and Philippine English), or dot pen[2] (Nepali English and South Asian English), is a pen that dispenses ink (usually in paste form) over a metal ball at its point, i.e., over a "ball point". The metals commonly used are steel, brass, or tungsten carbide.[3] The design was conceived and developed as a cleaner and more reliable alternative to dip pens and fountain pens, and it is now the world's most-used writing instrument;[4] millions are manufactured and sold daily.[5] It has influenced art and graphic design and spawned an artwork genre.

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]The concept of using a "ball point" within a writing instrument to apply ink to paper has existed since the late 19th century. In these inventions, the ink was placed in a thin tube whose end was blocked by a tiny ball, held so that it could not slip into the tube or fall out of the pen.

The first patent for a ballpoint pen[6][7] was issued on 30 October 1888 to John J. Loud,[8] who was attempting to make a writing instrument that would be able to write "on rough surfaces—such as wood, coarse wrapping paper, and other articles"[9] which fountain pens could not. Loud's pen had a small rotating steel ball held in place by a socket. Although it could be used to mark rough surfaces such as leather, as Loud intended, it proved too coarse for letter-writing. With no commercial viability, its potential went unexploited,[1] and the patent eventually lapsed.[10]

The manufacture of economical, reliable ballpoint pens as are known today arose from experimentation, modern chemistry, and the precision manufacturing capabilities of the early 20th century.[4] Patents filed worldwide during early development are testaments to failed attempts at making the pens commercially viable and widely available.[11] Early ballpoints did not deliver the ink evenly; overflow and clogging were among the obstacles faced by early inventors[who?].[5] If the ball socket were too tight or the ink too thick, it would not reach the paper. If the socket were too loose or the ink too thin, the pen would leak, or the ink would smear.[5] Ink reservoirs pressurized by a piston, spring, capillary action, and gravity would all serve as solutions to ink-delivery and flow problems.[12][13]

László Bíró, a Hungarian newspaper editor (later a naturalized Argentine) frustrated by the amount of time that he wasted filling up fountain pens and cleaning up smudged pages, noticed that inks used in newspaper printing dried quickly, leaving the paper dry and smudge-free. He decided to create a pen using the same type of ink.[5] Bíró enlisted the help of his brother György, a dentist with useful knowledge of chemistry,[14] to develop viscous ink formulae for new ballpoint designs.[4]

Bíró's innovation successfully coupled viscous ink with a ball-and-socket mechanism that allowed controlled flow while preventing ink from drying inside the reservoir.[5] Bíró filed for a British patent on 15 June 1938.[1][15][16]

In 1941, the Bíró brothers and a friend, Juan Jorge Meyne, fled Germany and moved to Argentina, where they formed "Bíró Pens of Argentina" and filed a new patent in 1943.[1] Their pen was sold in Argentina as the "Birome", from the names Bíró and Meyne, which is how ballpoint pens are still known in that country.[1] This new design was licensed by the British engineer Frederick George Miles and manufactured by his company Miles Aircraft, to be used by Royal Air Force aircrew as the "Biro".[17] Ballpoint pens were found to be more versatile than fountain pens, especially in airplanes, where fountain pens were prone to leak.[5]

Bíró's patent, and other early patents on ballpoint pens, often used the term "ball-point fountain pen".[18][self-published source?][19][20][21][22][23]

Postwar proliferation

[edit]

Following World War II, many companies vied to commercially produce their own ballpoint pen design. In pre-war Argentina, success of the Birome ballpoint was limited, but in mid-1945, the Eversharp Co., a maker of mechanical pencils, teamed up with Eberhard Faber Co. to license the rights from Birome for sales in the United States.[1][10]

In 1946, a Spanish firm, Vila Sivill Hermanos, began to make a ballpoint, Regia Continua, and from 1953 to 1957 their factory also made Bic ballpoints, on contract with the French firm Société Bic.[24]

During the same period, American entrepreneur Milton Reynolds came across a Birome ballpoint pen during a business trip to Buenos Aires, Argentina.[1][10] Recognizing commercial potential, he purchased several ballpoint samples, returned to the United States, and founded the Reynolds International Pen Company. Reynolds bypassed the Birome patent with sufficient design alterations to obtain an American patent, beating Eversharp and other competitors to introduce the pen to the US market.[1][10] Debuting at Gimbels department store in New York City on 29 October 1945,[10] for US$12.50 each (1945 US dollar value, about $212 in 2023 dollars),[10] "Reynolds Rocket" became the first commercially successful ballpoint pen.[1][5][25] Reynolds went to great extremes to market the pen, with great success; Gimbel's sold many thousands of pens within one week. In Britain, the Miles-(Harry) Martin pen company was producing the first commercially successful ballpoint pens there by the end of 1945.[1][26][27]

Neither Reynolds' nor Eversharp's ballpoint lived up to consumer expectations in America. Ballpoint pen sales peaked in 1946, and consumer interest subsequently plunged due to market saturation, going from luxury good to fungible consumable.[10] By the early 1950s the ballpoint boom had subsided and Reynolds' company folded.[1]

Paper Mate pens, among the emerging ballpoint brands of the 1950s, bought the rights to distribute their own ballpoint pens in Canada.[28] Facing concerns about ink-reliability, Paper Mate pioneered new ink formulas and advertised them as "banker-approved".[10] In 1954, Parker Pens released "The Jotter"—the company's first ballpoint—boasting additional features and technological advances which also included the use of tungsten-carbide textured ball-bearings in their pens.[1] In less than a year, Parker sold several million pens at prices between three and nine dollars.[1] In the 1960s, the failing Eversharp Co. sold its pen division to Parker and ultimately folded.[1]

Marcel Bich also introduced a ballpoint pen to the American marketplace in the 1950s, licensed from Bíró and based on the Argentine designs.[4][29] Bich shortened his name to Bic in 1953, forming the ballpoint brand Bic now recognized globally.[5] Bic pens struggled until the company launched its "Writes First Time, Every Time!"[30][31] advertising campaign in the 1960s.[5] Competition during this era forced unit prices to drop considerably.[5]

Inks

[edit]Ballpoint pen ink is normally a paste containing around 25 to 40 percent dye. The dyes are suspended in a mixture of solvents and fatty acids.[32] The most common of the solvents are benzyl alcohol or phenoxyethanol, which mix with the dyes and oils to create a smooth paste that dries quickly. This type of ink is also called "oil-based ink". The fatty acids help to lubricate the ball tip while writing. Hybrid inks also contain added lubricants in the ink to provide a smoother writing experience. The drying time of the ink varies depending upon the viscosity of the ink and the diameter of the ball.

In general, the more viscous the ink, the faster it will dry, but more writing pressure needs to be applied to dispense ink. But although they are less viscous, hybrid inks have a faster drying time compared to normal ballpoint inks. Also, a larger ball dispenses more ink and thus increases drying time.

The dyes used in blue and black ballpoint pens are basic dyes based on triarylmethane and acid dyes derived from diazo compounds or phthalocyanine. Common dyes in blue (and black) ink are Prussian blue, Victoria blue, methyl violet, crystal violet, and phthalocyanine blue. The dye eosin is commonly used for red ink.

The inks are resistant to water after drying but can be defaced by certain solvents which include acetone and various alcohols.

Types of ballpoint pens

[edit]

Ballpoint pens are produced in both disposable and refillable models. Refills allow for the entire internal ink reservoir, including a ballpoint and socket, to be replaced. Such characteristics are usually associated with designer-type pens or those constructed of finer materials. The simplest types of ballpoint pens are disposable and have a cap to cover the tip when the pen is not in use, or a mechanism for retracting the tip,[4] which varies between manufacturers but is usually a spring- or screw-mechanism.

Rollerball pens employ the same ballpoint mechanics, but with the use of water-based inks instead of oil-based inks.[33] Compared to oil-based ballpoints, rollerball pens are said to provide more fluid ink-flow, but the water-based inks will blot if held stationary against the writing surface. Water-based inks also remain wet longer when freshly applied and are thus prone to "smearing"—posing problems to left-handed people (or right handed people writing right-to-left script)—and "running", should the writing surface become wet.

Some ballpoint pens use a hybrid ink formulation whose viscosity is lower than that of standard ballpoint ink, but greater than rollerball ink.[32] The ink dries faster than a gel pen to prevent smearing when writing. These pens are better suited for left-handed persons. Examples are the Zebra Surari, Uni-ball Jetstream and Pilot Acroball ranges.[34] These pens are also labelled "extra smooth", as they offer a smoother writing experience compared to normal ballpoint pens.

Ballpoint pens with erasable ink were pioneered by the Paper Mate pen company.[35] The ink formulas of erasable ballpoints have properties similar to rubber cement, allowing the ink to be literally rubbed clean from the writing surface before drying and eventually becoming permanent.[35] Erasable ink is much thicker than standard ballpoint inks, requiring pressurized cartridges to facilitate inkflow—meaning they can also write upside-down. Though these pens are equipped with erasers, any eraser will suffice.[35]

Ballpoint tips are fitted with balls whose diameter can vary from 0.28 mm to 1.6 mm. The ball diameter does not correspond to the width of the line produced by the pen. The line width depends on various factors like the type of ink and pressure applied. Some standard ball diameters are: 0.3 mm, 0.38 mm, 0.4 mm, 0.5 mm, 0.7 mm (fine), 0.8 mm, 1.0 mm (medium), 1.2 mm and 1.4 mm (broad). Pens with ball diameters as small as 0.18 mm have been made by Japanese companies, but are extremely rare.

The inexpensive, disposable Bic Cristal (also simply "Bic pen" or "Biro") is reportedly the most widely sold pen in the world.[29][36] It was the Bic company's first product and is still synonymous with the company name.[37][38] The Bic Cristal is part of the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, acknowledged for its industrial design.[39][36] Its hexagonal barrel mimics that of a wooden pencil and is transparent, showing the ink level in the reservoir. Originally a sealed streamlined cap, the modern pen cap has a small hole at the top to meet safety standards, helping to prevent suffocation if children suck it into the throat.[40]

Multi-pens are pens that feature multiple varying colored pen refills. Sometimes ballpoint refills are combined with another non-ballpoint refill, usually a mechanical pencil. Sometimes ballpoint pens combine a ballpoint tip on one end and touchscreen stylus on the other.

Ballpoint pens are sometimes provided free by businesses, such as hotels and banks, printed with a company's name and logo. Ballpoints have also been produced to commemorate events, such as a pen commemorating the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy.[4] These pens, known as "advertising pens," are the same as standard ballpoint pen models, but have become valued among collectors.

Sometimes ballpoint pens are also produced as design objects. With cases made of metal or wood, they become individually styled utility objects.

Use of ballpoint pens in space

[edit]It is generally believed that gravity is needed to coat the ball with ink. In fact most ballpoint pens on the Earth do not work when writing upside-down because the Earth's gravity pulls the ink inside the pen away from the tip of the pen. However, in the microgravity environment of space a regular ballpoint pen can still work, pointed in any direction, because the capillary forces in the ink are stronger than non present gravitational forces. The functionality of a regular ballpoint pen in space was confirmed by ESA astronaut Pedro Duque in 2003.[41]

Technology developed by Fisher pens in the United States resulted in the production of what came to be known as the "Fisher Space Pen". Space Pens combine a more viscous ink with a pressurized ink reservoir[5] that forces the ink toward the point. Unlike a standard ballpoint's ink container, the rear end of a Space Pen's pressurized reservoir is sealed, eliminating evaporation and leakage,[5] thus allowing the pen to write upside-down, in zero-gravity environments, and allegedly underwater.[42] Astronauts have made use of these pens in outer space.[5]

As an art medium

[edit]

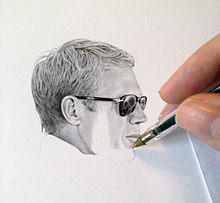

The ballpoint pen has proven to be a versatile art medium for both professional artists and amateur doodlers.[43] Low cost, availability, and portability are cited by practitioners as qualities which make this common writing tool a convenient art supply.[44] Some artists use them within mixed-media works, while others use them solely as their medium-of-choice.[45]

Effects not generally associated with ballpoint pens can be achieved.[46] Traditional pen-and-ink techniques such as stippling and cross-hatching can be used to create half-tones[47] or the illusion of form and volume.[48] For artists whose interests necessitate precision line-work, ballpoints are an obvious attraction; ballpoint pens allow for sharp lines not as effectively executed using a brush.[49] Finely applied, the resulting imagery has been mistaken for airbrushed artwork[50] and photography,[51] causing reactions of disbelief which ballpoint artist Lennie Mace refers to as the "Wow Factor".[49][50]

Famous 20th-century artists including Andy Warhol, have utilized the ballpoint pen during their careers.[52] Ballpoint pen artwork continues to attract interest in the 21st century, with many contemporary artists gaining recognition for their specific use of ballpoint pens as a medium. Korean-American artist Il Lee has been creating large-scale, abstract artwork since the late 1970s solely with ballpoint pens.[43] Since the 1980s, Lennie Mace creates imaginative, ballpoint-only artwork of varying content and complexity, applied to unconventional surfaces including wood and denim.[53] The artist coined terms such as "PENtings" and "Media Graffiti" to describe his varied output.[49] British artist James Mylne has been creating photo-realistic artwork using mostly black ballpoints, sometimes with minimal mixed-media color.[51]

The ballpoint pen has several limitations as an art medium. Color availability and sensitivity of ink to light are among concerns of ballpoint pen artists.[54] As a tool that uses ink, marks made with a ballpoint pen can generally not be erased.[49] Additionally, "blobbing" ink on the drawing surface and "skipping" ink-flow require consideration when drawing with a ballpoint pen.[45] Although the mechanics of ballpoint pens remain relatively unchanged, ink composition has evolved to solve certain problems over the years, resulting in unpredictable sensitivity to light and some extent of fading.[54]

Manufacturing

[edit]The common ballpoint pen is a product of mass production, with components produced separately on assembly lines.[55] Basic steps in the manufacturing process include the production of ink formulas, molding of metal and plastic components, and assembly.[4] Marcel Bich (leading to Société Bic) was involved in developing the production of inexpensive ballpoint pens.[5]

Although designs and construction vary between brands, basic components of all ballpoint pens are universal.[4] Standard components of a ballpoint tip include the freely rotating "ball" itself (distributing the ink on the writing surface), a "socket" holding the ball in place, small "ink channels" that provide ink to the ball through the socket, and a self-contained "ink reservoir" supplying ink to the ball.[5] In modern disposable pens, narrow plastic tubes contain the ink, which is compelled downward to the ball by gravity.[5] Brass, steel, or tungsten carbide are used to manufacture the ball bearing-like points,[5] then housed in a brass socket.[55]

The function of these components can be observed at a larger scale in the ball-applicator of roll-on antiperspirant. The ballpoint tip delivers the ink to the writing surface while acting as a "buffer" between the ink in the reservoir and the air outside, preventing the quick-drying ink from drying inside the reservoir. Modern ballpoints are said to have a two-year shelf life, on average.[5]

A ballpoint tip that can write comfortably for a long period of time is not easy to produce, as it requires high-precision machinery and thin high-grade steel alloy plates. China, which as of 2017[update] produces about 80 percent of the world's ballpoint pens, relied on imported ballpoint tips and metal alloys before 2017.[56]

Standards

[edit]The International Organization for Standardization has published standards for ball point and roller ball pens:

- ISO 12756

- 1998: Drawing and writing instruments – Ball point pens – Vocabulary[57]

- ISO 12757-1

- 1998: Ball point pens and refills – Part 1: General use[58]

- ISO 12757-2

- 1998: Ball point pens and refills – Part 2: Documentary use (DOC)[59]

- ISO 14145-1

- 1998: Roller ball pens and refills – Part 1: General use[60]

- ISO 14145-2

- 1998: Roller ball pens and refills – Part 2: Documentary use (DOC)[61]

Guinness World Records

[edit]- The world's largest functioning ballpoint pen was made by Acharya Makunuri Srinivasa in India. The pen measures 5.5 metres (18 ft 0.53 in) long and weighs 37.23 kilograms (82.08 lb).[62]

- The world's most popular pen is the Bic Cristal, with the 100 billionth model sold in September, 2006. The Bic Cristal was launched in December 1950 and roughly 57 are sold per second.[63]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bellis, Mary (15 April 2017). "How Laszlo Biro Changed the History of Ballpoint Pens". Thoughtco.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Karn, Sajan Kumar (2012). "On Nepalese English Discourse Granting Citizenship to English in Nepal via Corpus Building". Journal of NELTA. 16 (1–2): 30–41. doi:10.3126/nelta.v16i1-2.6127. ISSN 2091-0487. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "How does a ballpoint pen work?". Engineering. HowStuffWorks. 1998–2007. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perry, Romanowsky (January 1998). "How products are made". Ballpoint pen. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Russell-Ausley, Melissa (April 2000). "How Ballpoint Pens Work". Howstuffworks, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007) "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–20" Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 69

- ^ [Japes P. Mannings, "Reservoir, Fountain, and Stylographic Pens"], Journal of the Society of Arts, 27 October 1905, p. 1150

- ^ Great Britain Patent No. 15630, 30 October 2008

- ^ "Patent US392046 – op weym – Google Patents". Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ryan, James Gilbert; Schlup, Leonard C. (2006). Historical Dictionary of The 1940s. M.E. Sharpe, Inc. p. 40. ISBN 0-7656-0440-X. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Birome Ballpoint Pen Collection". Bios, Landmarks, Patents – ASME. ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers). 1996–2013. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007). "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–2005". Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 80

- ^ Webshark Ltd. – www.webshark.hu. "A porcelán-arany csoda". Herend. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007) "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–2005". Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 81

- ^ "The first complete specifications appear to be UK 498997, June 1938 and UK 512218, December 1938; his rather basic Hungarian patent 120037 was dated April 1938." Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007). "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–2005". Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 80

- ^ "La Birome". Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Maksel, Rebecca. "If You Like Ballpoint Pens, Thank the R.A.F." Air & Space Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Douglas E.; Chant, Stephen J. (2017). Patent Log: Innovative Patents that Advanced the United States Navy. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781105625626. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Books.[self-published source]

- ^ "Ball point fountain pen". United States Patent Office. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Patents.

- ^ "Red ball point fountain pen inks and colorants therefor". United States Patent Office. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Patents.

- ^ "Fountain pen of the ball point type". United States Patent Office. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Patents.

- ^ "Ball-point fountain pen". United States Patent Office. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Patents.

- ^ "Writing instrument". United States Patent Office. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Patents.

- ^ Francesc, Muñoz (10 July 2016). "El meu avi va fer la primera estilogràfica d'Espanya i el primer bolígraf d'Europa". El Punt Avui. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Stephen Van Dulken; Andrew Phillips (2002). Inventing the 20th century: 100 inventions that shaped the world. NYU Press. p. 106.

- ^ "Miles." Flight International, 28 August 1976, p. 513.

- ^ "The Biro Story." Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine comcast.net. Retrieved: 25 April 2012.

- ^ Cresce, Greg (11 August 2012). "book review, "Politics, human intrigue flow through ballpoint pen's history"". Gyorgy Moldova; Ballpoint: A tale of Genius and Grit, Perilous Times, and the Invention that Changed the Way We Write; Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Phaidon Design Classics- Volume 2, 2006 Phaidon Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7148-4399-7

- ^ "BIC Fight for Your Write".

- ^ "BIC".

- ^ a b "The Difference Between Ballpoint, Gel, and Rollerball Pens | JetPens". www.jetpens.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Ballpoint vs. Rollerball – What's The Difference?". Unsharpen.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Hybrid Ballpoint Showdown". The Well-Appointed Desk. 20 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b c V. Elaine Smay (1979). "New Designs; Ball-point pen uses erasable ink". Popular Science (July 1979, p. 20). Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Humble Masterpieces Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine – The Museum of Modern Art New York, 8 April – 27 September 2004.

- ^ "BIC Corporation – Company History". Fundinguniverse.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "History". Bicworld.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Décolletage Plastique Design Team. Bic Cristal® Ballpoint pen. 1950 – MoMA". Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "BICWorld.com FAQ – BIC World". Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "Pedro Duque's diary from space". www.esa.int. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Fisher Space Pen – About Us". Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ a b Genocchio, Benjamin (10 August 2007). "To See the World in Ballpoint Pen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Attewill, Fred (29 September 2011). "Artist wins £6,000 art prize after using 3p ballpoint pens from Tesco". Metro. Kensington, London: Associated Newspapers Ltd. ISSN 1469-6215. OCLC 225917520. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Johnson, Cathy (2010). Watercolor tricks & techniques: 75 new and classic painting secrets (illustrated, revised ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: North Light Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-60061-308-1. OCLC 299713330. Retrieved 30 March 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pen, Invention (21 March 2021). "Invention of Pen; history of Pen". 2 (15). Kanpur, India: The Helping Tech: 16. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mylne, James (2010). "About Ballpoints, & Using Them in Art". Biro Drawing.co.uk. James R. Mylne. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Tizon, Natalia (2007). Art of Sketching (illustrated ed.). New York: Sterling Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 9781402744235. OCLC 76951111. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Liddell, C.B. (3 April 2002). "The hair-raising art of Lennie Mace; Lennie Mace Museum". The Japan Times. Tokyo: Toshiaki Ogasawara. ISSN 0447-5763. OCLC 21225620. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Liddell, C.B. (January 2002). "Getting the ball rolling in harajuku". Tokyo Journal. 21 (241). Tokyo: Nexxus Communications K.K.: 36–37. ISSN 0289-811X. OCLC 13995159.

- ^ a b Garnham, Emily (16 April 2010). "Biro artist recreates Girl With A Pearl Earring masterpiece". Daily Express. London: Northern and Shell Media. OCLC 173337077. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Warhol, Andy; Slovak, Richard; Hunt, Timothy (2007). Warhol Polaroid Portraits. New York: McCaffrey Fine Art. pp. intro. ISBN 9780979048418. OCLC 420821909. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Honda, Takahiko (April 2011). "New York's Playful Ballpoint Picasso". 「月刊ギャラリー」(Gekkan Gallery Guide). 4. Tokyo: Gallery Station Co., Ltd.: 27.

- ^ a b Holben Ellis, Margaret (1995). The care of prints and drawings (reprint, illustrated ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman Altamira. pp. 101–103. ISBN 9780761991366. OCLC 33404294. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Dransfield, Rob; Needham, Dave (2005). GCE AS Level Applied Business Double Award for OCR. Heinemann Educational Publishers. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-435401-16-0. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Finally, China manufactures a ballpoint pen all by itself". washingtonpost.com. 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "ISO 12756:1998 – Drawing and writing instruments – Ball point pens and roller ball pens – Vocabulary j". Iso.org. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "ISO 12757-1:1998 – Ball point pens and refills – Part 1: General use". Iso.org. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2003. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "ISO 12757-2:1998 – Ball point pens and refills – Part 2: Documentary use (DOC)". Iso.org. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original on 25 August 2005. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "ISO 14145-1:1998 – Roller ball pens and refills – Part 1: General use". Iso.org. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2003. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "ISO 14145-2:1998 – Roller ball pens and refills – Part 2: Documentary use (DOC)". Iso.org. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2005. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "Largest ball point pen". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Pen - Best Selling". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- Fascinating facts about the invention of the Ballpoint Pen by Ladislas Biro in 1935 (archived 13 September 2019)

- Laszlo Biro on Jewish.hu's list of famous Hungarians (archived 22 May 2013)