William J. Burns (diplomat)

William J. Burns | |

|---|---|

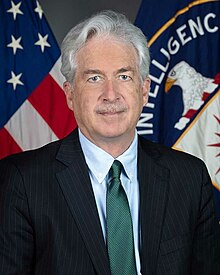

Official portrait, 2021 | |

| 8th Director of the Central Intelligence Agency | |

| Assumed office March 19, 2021 | |

| President | Joe Biden |

| Deputy | David S. Cohen |

| Preceded by | Gina Haspel |

| 17th United States Deputy Secretary of State | |

| In office July 28, 2011 – November 3, 2014 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | James Steinberg |

| Succeeded by | Antony Blinken |

| United States Secretary of State | |

| Acting January 20, 2009 – January 21, 2009[1] | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Condoleezza Rice |

| Succeeded by | Hillary Clinton |

| 20th Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs | |

| In office May 13, 2008 – July 28, 2011 | |

| President | George W. Bush Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | R. Nicholas Burns |

| Succeeded by | Wendy Sherman |

| United States Ambassador to Russia | |

| In office November 8, 2005 – May 13, 2008 | |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Alexander Vershbow |

| Succeeded by | John Beyrle |

| 20th Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs | |

| In office June 4, 2001 – March 2, 2005 | |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Edward S. Walker Jr. |

| Succeeded by | David Welch |

| United States Ambassador to Jordan | |

| In office August 9, 1998 – June 4, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Wesley Egan |

| Succeeded by | Edward Gnehm |

| 17th Executive Secretary of the United States Department of State | |

| In office January 16, 1996 – February 27, 1998 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Kenneth C. Brill |

| Succeeded by | Kristie Kenney |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Joseph Burns April 11, 1956 Fort Bragg, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Lisa Carty |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | La Salle University (BA) St John's College, Oxford (MPhil, DPhil) |

| Diplomatic service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | U.S. Department of State |

| Years of service | 1982–2014 |

| Rank | Career Ambassador |

William Joseph Burns (born April 11, 1956)[2] is an American diplomat and the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the Biden administration since March 19, 2021.[3] He previously served as U.S. deputy secretary of state from 2011 to 2014; in 2009 he served as acting secretary of state for a day, prior to the confirmation of Hillary Clinton. Burns retired from the U.S. Foreign Service in 2014 after a 32-year career. From 2014 to 2021, he served as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.[4][5]

Burns served as ambassador to Jordan from 1998 to 2001, Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs from 2001 to 2005, ambassador to Russia from 2005 to 2008 and Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs from 2008 to 2011.[6]

In January 2021, President Joe Biden nominated Burns to become CIA director.[7] He was unanimously confirmed by voice vote in the Senate on March 18, 2021, sworn in officially as director on March 19,[3] as well as ceremonially sworn in by Vice President Kamala Harris on March 23.[8][9] In July 2023, Biden elevated Burns to a position in his cabinet, a largely symbolic action.[10]

Early life and education

[edit]Burns was born at Fort Liberty (formerly Fort Bragg), North Carolina, in 1956.[11] He is the son of Peggy Cassady and William F. Burns, who was a United States Army major general, a deputy assistant secretary of state for arms control, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, director of the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in 1988–1989 in the Ronald Reagan administration, in addition to his service as the first U.S. special envoy to denuclearization negotiations with former Soviet countries under the legislation sponsored by U.S. senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar.[12][13][14]

Burns attended Trinity High School in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, where he graduated valedictorian in 1973. He then studied history at La Salle University and graduated with honors in 1978. He was then awarded a Marshall Scholarship to study at the University of Oxford, becoming La Salle's first Marshall Scholar. He earned M.Phil. and D.Phil. degrees in international relations from St. John's College, Oxford.[15] His D.Phil. thesis, Economic Aid and American Policy toward Egypt, 1955–1981, was completed in 1985.

While at Oxford, Burns was also a member of the men's basketball team.[16]

Career

[edit]U.S. Foreign Service

[edit]Burns entered the Foreign Service in 1982 and served as deputy secretary of state from 2011 to 2014. He had served as under secretary for political affairs from 2008 to 2011. He was ambassador to Russia from 2005 to 2008, assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs from 2001 to 2005, and ambassador to Jordan from 1998 to 2001. He had also been Executive Secretary of the State Department and special assistant to secretaries of state Warren Christopher and Madeleine Albright, minister-counselor for political affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, acting director and principal deputy director of the State Department's Policy Planning Staff, as well as special assistant to the president and senior director for Near East and South Asian affairs at the United States National Security Council.[4]

In 2008, Burns was nominated by President George W. Bush and confirmed by the Senate as a career ambassador, the highest rank in the U.S. Foreign Service, equivalent to a four-star general officer in the U.S. Armed Forces. Promotions to the rank are rare.

In 2008, Burns wrote to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice: "Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin's sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests."[17]

A leaked diplomatic cable that Burns signed as ambassador to Russia in August 2006 provided a detailed eyewitness account of the lavish wedding organized in Makhachkala by Russian State Duma member and Dagestan Oil Company chief Gadzhi Makhachev for his son. The wedding lasted for two days; its attendees included Chechnya's Ramzan Kadyrov. An FSB colonel sitting next to the cable's authors tried to add "cognac" to their wine until an FSB general told him to stop.[18][19] In 2015, Burns told Gideon Rachman of the Financial Times that the cable had been "largely written by his colleagues," with Rachman remarking that the telegram had gained a reputation of "a minor classic of comic writing, its tone very much not what one might expect of a diplomatic cable."[20] In June 2013, Andrew Kuchins remarked about Burns's stint in Moscow, "It was a period when the relationship was deteriorating very significantly, but he was personally respected by Russian authorities as a consummate professional diplomat."[21]

In 2013, Burns and Jake Sullivan led the secret bilateral channel with Iran that led to the interim agreement between Iran and the P5+1 and ultimately the Iran nuclear deal.[22][2] Burns was reported to be "in the driver's seat" of the American negotiating team for the interim agreement. Burns had met secretly with Iranian officials as early as 2008, when President George W. Bush dispatched him to do so.[23]

In a piece published in The Atlantic in April 2013, Nicholas Kralev praised him as the "secret diplomatic weapon" deployed against "some of the thorniest foreign policy challenges of the US."[24]

Burns retired from the Foreign Service in 2014, later becoming president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.[3]

In November 2020, as Burns's name was being cited by press as one of several possible candidates to be nominated by Joe Biden for secretary of state, Russia's broadsheet Kommersant stated that its sources "in the state structures" of the Russian Federation agreed that his candidacy would "be the most advantageous for Moscow of all the five cited" in the media.[25]

Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

[edit]

On January 11, 2021, Joe Biden announced he planned to nominate Burns as director of the Central Intelligence Agency, saying Burns shared his belief "that intelligence must be apolitical and that the dedicated intelligence professionals serving our nation deserve our gratitude and respect."[26][27]

On February 24, his nomination was well received in the confirmation hearing in the Senate.[28] On March 2, the Senate Intelligence Committee unanimously approved Burns's nomination, setting him up for a final floor vote.[29] On March 18, Burns was confirmed to the role with unanimous consent after Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) lifted his hold on the nomination.[30] He was officially sworn in as Director of the Central Intelligence Agency on March 19.[3][8]

In his confirmation hearing before the Senate, Burns said, "an adversarial, predatory Chinese leadership poses our biggest geopolitical test".[31] He said China was working to "methodically strengthen its capabilities to steal intellectual property, repress its own people, bully its neighbors, expand its global reach and build influence in American society."[32]

In April 2021, Biden announced his intention to withdraw all regular U.S. troops from Afghanistan by September 2021. Burns told the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee on April 14, 2021, that "[t]here is a significant risk once the U.S. military and the coalition militaries withdraw" but added that the U.S. would retain "a suite of capabilities."[33] On August 23, 2021, Burns held a secret meeting in Kabul with Taliban leader Abdul Ghani Baradar, who returned to Afghanistan from exile in Qatar, to discuss the August 31 deadline for a U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan.[34][35]

In early November 2021, Burns flew to Moscow, notifying Nikolai Patrushev, the secretary of Putin's security council, that the United States believed Putin was considering a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Burns warned that if Putin were to invade Ukraine, the West would respond in a way that would have severe consequences for Russia.[36] John Sullivan, at the time the American ambassador to Russia, recounted that Patrushev was undeterred by Burns's warnings. Upon his return to Washington, Burns informed Biden that Putin had all but made up his mind to take over Ukraine and that the Russians had absolute confidence victory would come swiftly.[37]

On March 31, 2022, Burns tested positive for COVID-19, a day after meeting with President Biden during a socially distanced meeting at the White House.[38]

In April 2022, Burns warned that Vladimir Putin's "desperation" over Russia's failures in Ukraine could lead to the use of tactical nuclear weapons or "low-yield nuclear weapons."[39] That same month, Burns traveled to Saudi Arabia to meet with the crown prince and asked him to increase the country's oil production. They also discussed Saudi weapons purchases from China.[40] on July 31, 2022, he oversaw the operation that killed the terrorist leader Ayman al-Zawahiri.[41]

In May 2023, Burns made a secret visit to China to ease tensions with the country.[42]

After the beginning of the war between Hamas and Israel, Burns pushed for a deal with Hamas to secure the release of Israeli hostages.[43]

Publications

[edit]Books

[edit]His memoir, The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal, was published by Random House in 2019. It was published in conjunction with an archive of nearly 100 declassified diplomatic cables.[44] International relations scholars who reviewed the book were mostly positive.[45][46][47]

Articles

[edit]- Spycraft and Statecraft, Foreign Affairs, January 30, 2024[48]

Others

[edit]Burns's dissertation was published in 1985 as Economic Aid and American Policy Toward Egypt, 1955–1981.[49]

Awards

[edit]Burns is the recipient of three Presidential Distinguished Service Awards and several Department of State awards, including three Secretary's Distinguished Service Awards, the Secretary's Career Achievement Award, the Charles E. Cobb Jr. Award for Initiative and Success in Trade Development (2006), the Robert C. Frasure Memorial Award (2005), and the James Clement Dunn Award (1991). He also received the Department of Defense Award for Distinguished Public Service (2014), the U.S. Intelligence Community Medallion (2014), and the Central Intelligence Agency's Agency Seal Medal (2014).[citation needed]

In 1994, Burns was named to Time's lists of "50 Most Promising American Leaders Under Age 40" and "100 Most Promising Global Leaders Under Age 40".[50] He was named Foreign Policy's "Diplomat of the Year" in 2013.[51] He is the recipient of Anti-Defamation League's Distinguished Statesman Award (2014),[52] the Middle East Institute's Lifetime Achievement Award (2014), and the American Academy of Diplomacy's Annenberg Award for Diplomatic Excellence (2015).[53] Burns received the American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award (2022).[54][55]

Burns holds four honorary doctoral degrees and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[15] He is also an honorary Fellow, St. John's College, Oxford, (from 2012).[56]

Foreign government decorations

[edit]- Commandeur, Legion of Honour (France)[57][58]

- Knight Commander, Order of Merit (Germany)[58]

- Grand Cordon, Order of the Rising Sun (Japan)[59]

- Marshall Medal (UK)[60]

- Commendatore, Order of Merit (Italy)[61]

- First Order, Al Kawkab Medal (Jordan)[58]

- Commander with star, Royal Order of St Olav (Norway)[62]

Personal life

[edit]Burns is married to Lisa Carty, a former diplomat and current UN OCHA senior official,[63] and has two daughters. He speaks English, French, Russian, and Arabic.[64]

Jeffrey Epstein Meetings

[edit]In 2023, The Wall Street Journal reported that Burns allegedly had three scheduled meetings with Jeffrey Epstein in 2014, according to 'documents' and 'calendars' in their possession. At the time, Burns was deputy secretary of state, and Epstein had already pleaded guilty to the charge of procuring for prostitution a girl below age 18.[65]

References

[edit]- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Condoleezza Rice (1954–)". U.S. Department of State – Office of the Historian. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

Under Secretary for Political Affairs William J. Burns served as Acting Secretary of State, January 20–21, 2009.

- ^ a b Barnes, Julian E.; Verma, Pranshu (January 11, 2021). "William Burns Is Biden's Choice for C.I.A. Director". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "About CIA - Director of the CIA". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ambassador William J. Burns Named Next Carnegie President". National Endowment for Democracy (NEFD). October 28, 2014. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "US Senate confirms Biden's health and CIA chiefs". www.aljazeera.com. March 18, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "William Burns to retire". POLITICO. Associated Press. April 11, 2014. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Durbin Meets With William Burns, Biden Nominee For CIA Director". Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Harris calls Boulder shooting 'absolutely tragic'". The Hill. March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "Bill Burns Sworn in as CIA Director - CIA". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on April 6, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Shear, Michael D. (July 21, 2023). "Biden Elevates C.I.A. Director to Become a Member of the Cabinet". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "Appointment of William J. Burns as a Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs". reaganlibrary.gov. September 26, 1988. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Nomination of William F. Burns To Be Director of the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency". The American Presidency Project. January 7, 1988.

- ^ Major General William F. Burns (Ret.) (July 8, 2005). "Arms Control Today". The Arms Control Association.

- ^ Pyotr Cheryomushkin (April 27, 2008). "Ядерный дипломат". Коммерсантъ. Kommersant.

- ^ a b "William J. Burns". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ "Burns, William J." United States Department of State. June 4, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State.

- ^ Shifrinson, Joshua; Wertheim, Stephen (December 23, 2021). "Acting too aggressively on Ukraine may endanger it — and Taiwan". Washington Post. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Wedding in the Caucasus: The US Ambassador Learns that Cognac Is Like Wine". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "US embassy cables: A wedding feast, the Caucasus way". The Guardian. December 1, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Lunch with the FT: Bill Burns". Financial Times. November 6, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Taps Kerry's Deputy as Point Man With Russia on Snowden". The Moscow Times. June 13, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (April 11, 2014). "Diplomat Who Led Secret Talks with Iran Plans to Retire". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Guy. "Career diplomat William Burns steered the Iran talks quietly though rounds of negotiations". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Kralev, Nicholas (April 4, 2013). "The White House's Secret Diplomatic Weapon". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Джо Байден в первых лицах: Что ждать России от внешнеполитической команды будущего президента США". Kommersant. November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "For CIA director, Biden taps veteran diplomat William Burns". POLITICO. January 11, 2021.

- ^ Gramer, Jack Detsch, Amy Mackinnon, Robbie (January 11, 2021). "Biden Taps Career Diplomat William Burns as CIA Director".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "William Burns, Biden's CIA pick, vows "intensified focus" on the competition with China". CBS News. February 24, 2021.

- ^ Matishak, Martin, "Senate Intel unanimously approves Burns to be CIA director: Timing for the final confirmation vote remains unclear" (March 2, 2021). Politico. www.google.com/amp/s/www.politico.com/amp/news/2021/03/02/senate-approves-burns-cia-472685. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Jeremy Herb (March 18, 2021). "Senate confirms William Burns to be next CIA director after Cruz lifts hold". CNN. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "China's 'adversarial, predatory' leadership on radar: Burns". Financial Review. February 25, 2021.

- ^ "CIA Nominee William Burns Talks Tough On China". NPR. February 24, 2021.

- ^ Putz, Catherine (April 15, 2021). "Biden Announces Plan for US Exit from Afghan War, Urges Attention to Future Challenges". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021.

- ^ "CIA director met Taliban leader in Afghanistan on Monday -sources". Reuters. August 24, 2021.

- ^ "CIA chief secretly met with Taliban leader in Kabul: Report". Al-Jazeera. August 24, 2021.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Troianovski, Anton; Al-Hlou, Yousur; Froliak, Masha; Entous, Adam; Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (December 17, 2022). "Putin's War: The Inside Story of a Catastrophe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Troianovski, Anton; Al-Hlou, Yousur; Froliak, Masha; Entous, Adam; Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (December 17, 2022). "Putin's War: The Inside Story of a Catastrophe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (March 31, 2022). "CIA Director William Burns tests positive for Covid after meeting with Biden, but is not considered a close contact". CNBC. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Sen. Mitt Romney suggests 'NATO could engage' in Ukraine, 'potentially obliterating Russia's struggling military' if Putin used nuclear weapons". Business Insider. May 22, 2022.

- ^ "Inside the Secret Meeting Between the CIA Director and Saudi Crown Prince". The Intercept. May 13, 2022.

- ^ Baker, Peter; Cooper, Helene; Barnes, Julian; Schmitt, Eric (August 1, 2022). "U.S. Drone Strike Kills Ayman al-Zawahri, Top Qaeda Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "CIA chief made secret visit to China in bid to thaw relations". Financial Times. June 2, 2023.

- ^ "CIA director pushes big hostage deal in secret meeting with Mossad chief". The Washington Post. November 28, 2023.

- ^ Axios (March 11, 2019). "New book "The Back Channel" from former U.S. ambassador reveals warnings about Russia". Axios. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Colbourn, Susan; Goldgeier, James; Jentleson, Bruce W.; Lebovic, James; Charles, Elizabeth C.; Wilson, James Graham; Burns, William J. (December 17, 2019). "Roundtable 11-8 on The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal". H-Diplo | ISSF. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Gavin, Francis J. (December 12, 2019). "Bill burns and the lost art of diplomacy". Journal of Strategic Studies. 44 (7): 1094–1102. doi:10.1080/01402390.2019.1692661. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 213144471.

- ^ "Blame It on the Blob? How to Evaluate American Grand Strategy". War on the Rocks. August 21, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Burns, William J. (January 30, 2024). "Spycraft and Statecraft". Foreign Affairs. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ SUNY Press. www.sunypress.edu/p-193-economic-aid-and-american-polic.aspx. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "What Happened to the 'Future Leaders' of the 1990s?". Time. Archived from the original on March 31, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Bill Burns Honored as Diplomat of the Year". foreignpolicy.com. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Deputy Secretary of State Bill Burns Presented with ADL Award". www.adl.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Walter and Leonore Annenberg Excellence in Diplomacy Award". The American Academy of Diplomacy. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "2022 Summit". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "RAI in America". www.rai.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on June 15, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ French Embassy U.S. [@franceintheus] (March 7, 2018). "Today, we are here to honor one of the greatest diplomats of our time" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c Redaksi, Tim (January 11, 2021). "Ini Profil William Burns, Direktur CIA Pilihan Joe Biden". Voice of Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "受章者(その3止)". mainichi.jp (in Japanese). April 29, 2018. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Marshall Medal - Marshall Scholarships". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ "GAZZETTA UFFICIALE" (in Italian). May 10, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Tildelinger av ordener og medaljer". www.kongehuset.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ Burns, William (February 9, 2021). "Questionnaire for Completion by Presidential Nominees" (PDF). Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Dorman, Shawn (May 2019). "The Diplomacy Imperative: A Q&A with William J. Burns". American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Khadeeja, Safdar; Benoit, David (April 30, 2023). "Epstein's Private Calendar Reveals Prominent Names, Including CIA Chief, Goldman's Top Lawyer". Wall Street Journal.

William Burns, director of the Central Intelligence Agency since 2021, had three meetings scheduled with Epstein in 2014, when he was deputy secretary of state, the documents show. They first met in Washington and then Mr. Burns visited Epstein's townhouse in Manhattan. [...] Mr. Burns, 67 years old, a career diplomat and former ambassador to Russia, had meetings with Epstein in 2014 when Mr. Burns was deputy secretary of state. A lunch was planned that August at the office of law firm Steptoe & Johnson in Washington. Epstein scheduled two evening appointments that September with Mr. Burns at his townhouse, the documents show. After one of the scheduled meetings, Epstein planned for his driver to take Mr. Burns to the airport.

Further reading

[edit]- "Iranian-American negotiations : an interview with Ambassador William J. Burns". Journal of International Affairs. 69 (2): 177–183. Spring–Summer 2016.[a]

- Notes

- ^ Online version is titled "An interview with Ambassador William J. Burns on Iranian-American negotiations".

External links

[edit]- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "Biography of William J. Burns". United States Department of State. June 9, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- United States Embassy in Moscow: Biography of the Ambassador

- 1956 births

- Acting United States secretaries of state

- Alumni of St John's College, Oxford

- Ambassadors of the United States to Jordan

- Ambassadors of the United States to Russia

- Assistant Secretaries of State for the Near East and North Africa

- Biden administration cabinet members

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Directors of the Central Intelligence Agency

- La Salle University alumni

- Living people

- Marshall Scholars

- Obama administration cabinet members

- People from Fort Liberty, North Carolina

- Under Secretaries of State for Political Affairs

- United States Career Ambassadors

- United States deputy secretaries of state