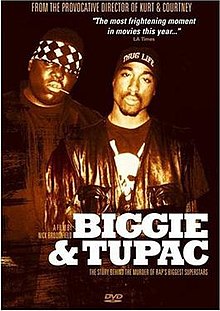

Biggie & Tupac

| Biggie & Tupac | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Nick Broomfield |

| Produced by | Nick Broomfield Michele D'Acosta |

| Starring | Christopher Wallace (archive footage) Tupac Shakur (archive footage) Nick Broomfield Russell Poole Voletta Wallace Billy Garland David Hicken Suge Knight |

| Cinematography | Joan Churchill |

| Edited by | Mark Atkins Jaime Estrada Torres |

| Music by | Christian Henson |

| Distributed by | Roxie Releasing Lions Gate Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 min. |

| Language | English |

Biggie & Tupac is a 2002 feature-length documentary film about the murdered American rappers Christopher "Notorious B.I.G." Wallace and Tupac Shakur by Nick Broomfield.

Broomfield suggests the two murders were planned by Suge Knight, head of Death Row Records. Collusion by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is also implied.[1] While the film remains inconclusive, when asked "Who killed Tupac?" in a BBC Radio interview dated March 7, 2005, Broomfield stated (quoting Snoop Dogg) "The big guy next to him in the car... Suge Knight."

Content

[edit]The film alleges that Suge Knight had Tupac killed before he could part ways with Knight's Death Row Records label and conspired to kill Biggie Smalls to divert attention from himself in the Tupac murder.[2]

Broomfield's documentary is based on the theory and interviews of ex-detective Russell Poole. Poole claimed that the L.A.P.D. conspired to cover up Knight's conspiracy to kill both Tupac and Biggie. Ex-detective Russell Poole suspected ex-cop David Mack, and Amir Muhammed to have worked with Suge Knight to kill Biggie. Poole also alleged that he was forced out of the department when he brought information to his superiors incriminating fellow officers who had worked side jobs as bodyguards for Knight and his record label.

A key source for Poole's theory is Kevin Hackie. Hackie implicates Suge Knight and David Mack along with supposed crooked cops in the murder of Biggie. When pressed by Broomfield in the film, Hackie agrees that Harry Billups, also known as Amir Muhammed, was involved in the murder, although Hackie says he does not know why. Hackie, a former Death Row bodyguard, wrote in a statement filed June 6, 2004 that he had "personal knowledge" about Wallace's slaying, alleging that "persons within Death Row Records offered $25,000 to a law enforcement officer" to kill Wallace.[3]

Criticism

[edit]Broomfield's documentary is described by the New York Times[4] as a "largely speculative" and "circumstantial"[4] account relying on flimsy evidence, failing to "present counter-evidence" or "question sources." As The Courant noted:

Broomfield's interview subjects aren't the most credible bunch. They include bounty hunter and ex-con Kevin Hackie, an ex-LAPD officer [Russell Poole on whose theory Broomfield's film is built] who talks about mysterious documents that never turn up; Mark Hyland, known for some reason as the Bookkeeper, who is in prison awaiting trial on 37 counts of impersonating a lawyer when he tells Broomfield that he was present when Knight and crooked cops arranged a hit on Biggie; and Biggie's mother, friends and bodyguard, who obviously have no reason to present Wallace as anything less than a hip-hop martyr.[2]

Moreover, the motive suggested for the murder of Biggie (as in the Russell Poole theory on which it relied)—to decrease suspicion for the Shakur shooting six months earlier—was, as The New York Times phrased it, "unsupported in the film."[4]

Later events

[edit]In an interview, Hackie later told the Los Angeles Times that he suffered memory lapses due to psychiatric medications.[3] The Wallace family used his claims in the film as the basis of their $500 million lawsuit against the city of L.A. for Biggie's death. But Hackie later told the LA Times that the Wallace attorneys had altered his statements and he did not testify in their suit.[3] (The 500 million dollar suit was dismissed in 2010.)

A 2005 article in the LA Times, saying that another source for the Poole/Sullivan theory accusing Amir Muhammed, David Mack, Suge Knight and the L.A.P.D. in the Wallace suit was a schizophrenic known as "Psycho Mike" who confessed to hearsay and memory lapses and falsely identifying Amir Muhammed.[5] John Cook of Brill's Content noted that the LA Times article "demolished" [6] the Poole-Sullvan theory of Biggie's murder represented in the film.

In contrast to Broomfield's implication of Suge Knight in the death of Tupac, a 2002 two-part series by reporter Chuck Philips with the Times, titled "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?" based on a year-long investigation, reconstructing the events leading up to Shakur's murder including police affidavits, court documents and interviews with investigators, supposed witnesses to the crime and members of the Southside Crips [7][8] claimed that "the shooting was carried out by a Compton gang called the Southside Crips to avenge the beating of one of its members by Shakur a few hours earlier. Orlando Anderson, the Crip whom Shakur had attacked, fired the fatal shots. Las Vegas police discounted Anderson as a suspect and interviewed him only once, briefly. He was later killed in an unrelated gang shooting."[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Biggie & Tupac, rogerebert.com

- ^ a b Danton, Eric (November 9, 2003). "Biggie (rip) Vs. Tupac (rip)". The Courant. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c Philips, Chuck (June 20, 2005). "Witness in B.I.G. case says his memory's bad". LA Times. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c Leland, John (October 7, 2002). "New Theories Stir Speculation On Rap Deaths". New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 3, 2005). "Informant in Rap Star's Slaying Admits Hearsay". LA Times. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Philips, Chuck (September 6, 2002). "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?". LA Times. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). "How Vegas police probe floundered in Tupac Shakur case". LA Times. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

External links

[edit]- 2002 films

- 2002 documentary films

- Documentary films about African-American gangs

- Documentary films about hip-hop music and musicians

- Films directed by Nick Broomfield

- Works about Tupac Shakur

- The Notorious B.I.G.

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s British films

- British musical documentary films

- Films scored by Christian Henson

- English-language documentary films