Bernie Madoff

Bernie Madoff | |

|---|---|

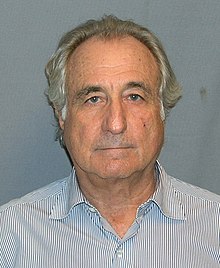

Madoff in a 2009 mugshot | |

| Born | Bernard Lawrence Madoff April 29, 1938 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 14, 2021 (aged 82) Butner, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Education |

|

| Occupations | |

| Employer | Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities[1] (founder) |

| Known for | Being the chairman of Nasdaq and the Madoff investment scandal |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Conviction(s) | March 12, 2009 (pleaded guilty) |

| Criminal charge | Securities fraud, investment advisor fraud, mail fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, false statements, perjury, making false filings with the SEC, theft from an employee benefit plan |

| Penalty | 150 years imprisonment, forfeiture of US$17.179 billion, lifetime ban from securities industry |

Date apprehended | December 11, 2008 |

Bernard Lawrence Madoff (/ˈmeɪdɔːf/ MAY-dawf;[2] April 29, 1938 – April 14, 2021) was an American financial criminal and financier who was the admitted mastermind of the largest known Ponzi scheme in history, worth an estimated $65 billion.[3][4] He was at one time chairman of the Nasdaq stock exchange.[5] Madoff's firm had two basic units: a stock brokerage and an asset management business; the Ponzi scheme was centered in the asset management business.

Madoff founded a penny stock brokerage in 1960, which eventually grew into Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities.[6] He served as the company's chairman until his arrest on December 11, 2008.[7][8] That year, the firm was the 6th-largest market maker in S&P 500 stocks.[9] While the stock brokerage part of the business had a public profile, Madoff tried to keep his asset management business low profile and exclusive.

At the firm, he employed his brother Peter Madoff as senior managing director and chief compliance officer, Peter's daughter Shana Madoff as the firm's rules and compliance officer and attorney, and his now-deceased sons Mark Madoff and Andrew Madoff. Peter was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2012,[10] and Mark hanged himself in 2010, exactly two years after his father's arrest.[11][12][13][14] Andrew died of lymphoma on September 3, 2014.[15]

On December 10, 2008, Madoff's sons Mark and Andrew told authorities that their father had confessed to them that the asset management unit of his firm was a massive Ponzi scheme, and quoted him as saying that it was "one big lie".[16][17][18] The following day, agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested Madoff and charged him with one count of securities fraud. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had previously conducted multiple investigations into his business practices but had not uncovered the massive fraud.[9] On March 12, 2009, Madoff pleaded guilty to 11 federal felonies and admitted to turning his wealth management business into a massive Ponzi scheme.

The Madoff investment scandal defrauded thousands of investors of billions of dollars. Madoff said that he began the Ponzi scheme in the early 1990s, but an ex-trader admitted in court to faking records for Madoff since the early 1970s.[19][20][21] Those charged with recovering the missing money believe that the investment operation may never have been legitimate.[22][23] The amount missing from client accounts was almost $65 billion, including fabricated gains.[24]

The Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) trustee estimated actual direct losses to investors of $18 billion,[22] of which $14.418 billion has been recovered and returned, while the search for additional funds continues.[25] On June 29, 2009, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison, the maximum sentence allowed.[26][27][28][29] On April 14, 2021, he died at the Federal Medical Center, Butner, in North Carolina, from chronic kidney disease.[30][31][32][33]

Early life

[edit]Madoff was born on April 29, 1938, in Brooklyn, New York City, to Sylvia (Muntner) and Ralph Madoff, who was a plumber and stockbroker.[34][31][35][36] His family was Jewish.[37] Madoff's grandparents were emigrants from Poland, Romania, and Austria.[38] He was the second of three children; his siblings are Sondra Weiner and Peter Madoff.[39][40] His family later moved to Queens, and Madoff graduated from Far Rockaway High School in 1956.[41]

Madoff attended the University of Alabama for one year, where he became a brother of the Tau Chapter of the Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity, then transferred to and graduated from Hofstra University in 1960 with a Bachelor of Arts in political science.[42][43] Madoff briefly attended Brooklyn Law School, but left after his first year to start Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and work for himself.[44][43][32]

Career

[edit]In 1960, Madoff founded Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC as a broker-dealer for penny stock with $5,000 (equivalent to $51,000 in 2023)[45] that he earned from working as a lifeguard and irrigation sprinkler installer,[46] and a loan of $50,000 from his father-in-law, accountant Saul Alpern, who referred a circle of friends and their families.[47] Carl J. Shapiro was one such early customer, investing $100,000.[33]

Initially, the firm made markets (quoted bid and ask prices) via the National Quotation Bureau's Pink Sheets. In order to compete with firms that were members of the New York Stock Exchange trading on the stock exchange's floor, his firm began using innovative computer information technology to disseminate its quotes.[48] After a trial run, the technology that the firm helped to develop became the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations Stock Market (Nasdaq).[49] After 41 years as a sole proprietorship, the Madoff firm incorporated in 2001 as a limited liability company with Madoff as the sole shareholder.[50]

The firm functioned as a third market trading provider, bypassing exchange specialist firms by directly executing orders over the counter from retail brokers.[51] At one point, Madoff Securities was the largest market maker at the Nasdaq, and in 2008 was the sixth-largest market maker in S&P 500 stocks.[48] The firm also had an investment management and advisory division, which it did not publicize, that was the focus of the fraud investigation.[52]

Madoff was "the first prominent practitioner"[53] of payment for order flow, in which a dealer pays a broker for the right to execute a customer's order. This has been called a "legal kickback".[54] Some academics have questioned the ethics of these payments.[55][56] Madoff argued that these payments did not alter the price that the customer received.[57] He viewed the payments as a normal business practice:

If your girlfriend goes to buy stockings at a supermarket, the racks that display those stockings are usually paid for by the company that manufactured the stockings. Order flow was an issue that attracted a lot of attention but was grossly overrated.[57]

Madoff was active with the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), a self-regulatory securities-industry organization. He served as chairman of its board of directors, and was a member of its board of governors.[58]

Personal life

[edit]Madoff met Ruth Alpern while attending Far Rockaway High School and the two began dating. Ruth graduated from high school in 1958, and earned her bachelor's degree at Queens College.[59][60] On November 28, 1959, Madoff married Alpern.[40][61] She was employed at the stock market [clarification needed] in Manhattan before[62] working in Madoff's firm, and she founded the Madoff Charitable Foundation.[63] Bernard and Ruth Madoff had two sons: Mark (1964–2010),[64] a 1986 graduate of the University of Michigan, and Andrew (1966–2014),[65][66] a 1988 graduate of University of Pennsylvania's Wharton Business School.[67][68] Both sons later worked in the trading section alongside paternal cousin Charles Weiner.[48][69]

Several family members worked for Madoff. His younger brother, Peter,[70] an attorney, was senior managing director and chief compliance officer, and Peter's daughter, Shana Madoff, also an attorney, was the firm's compliance attorney.

Over the years, Madoff's sons had borrowed money from their parents, to purchase homes and other property. Mark Madoff owed his parents $22 million, and Andrew Madoff owed them $9.5 million. There were two loans in 2008 from Bernard Madoff to Andrew: $4.3 million on October 6, and $250,000 on September 21.[71] Andrew owned a Manhattan apartment and a home in Greenwich, Connecticut, as did his brother Mark,[62] prior to his death.[12] Both sons used outside investment firms to run their own private philanthropic foundations.[46][62][72] In March 2003, Andrew Madoff was diagnosed with mantle cell lymphoma and eventually returned to work. He was named chairman of the Lymphoma Research Foundation in January 2008, but resigned shortly after his father's arrest.[62]

Peter Madoff (and Andrew Madoff, before his death) remained the targets of a tax fraud investigation by federal prosecutors, according to The Wall Street Journal. David Friehling, Bernard Madoff's tax accountant, who pleaded guilty in a related case, was reportedly assisting in the investigation. According to a civil lawsuit filed in October 2009, trustee Irving Picard alleges that Peter Madoff deposited $32,146 into his Madoff accounts and withdrew over $16 million; Andrew deposited almost $1 million into his accounts and withdrew $17 million; Mark deposited $745,482 and withdrew $18.1 million.[73]

Bernard lived in Roslyn, New York, in a ranch house through the 1970s. In 1980, he purchased an ocean-front residence in Montauk, New York, for $250,000.[74] His primary residence was on Manhattan's Upper East Side,[75] and he was listed as chairman of the building's co-op board.[76] He also owned a home in France and an 8,700-square-foot house in Palm Beach, Florida, where he was a member of the Palm Beach Country Club, where he searched for targets of his fraud.[77][78][79] Madoff owned a 55-foot (17 m) sportfishing yacht named Bull.[76][44] All three of his homes were auctioned by the U.S. Marshals Service in September 2009.[80][81]

Sheryl Weinstein, former chief financial officer of Hadassah, disclosed in a memoir that she and Madoff had had an affair more than 20 years earlier. As of 1997, when Weinstein left, Hadassah had invested a total of $40 million with Bernie Madoff. By the end of 2008, Hadassah had withdrawn more than $130 million from its Madoff accounts and contends its accounts were valued at $90 million at the time of Madoff's arrest. At the victim impact sentencing hearing, Weinstein testified, calling him a "beast".[82][83] According to a March 13, 2009, filing by Madoff, he and his wife were worth up to $126 million, plus an estimated $700 million for the value of his business interest in Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC.[84]

On the morning of December 11, 2010 – exactly two years after Bernard's arrest – his son Mark was found dead in his New York City apartment. The city medical examiner ruled the cause of death as suicide by hanging.[12][13][14][11]

During a 2011 interview on CBS, Ruth Madoff claimed she and her husband had attempted suicide after his fraud was exposed, both taking "a bunch of pills" in a suicide pact on Christmas Eve 2008.[4][85] In November 2011, former Madoff employee David Kugel pleaded guilty to charges that arose out of the scheme. He admitted having helped Madoff create a phony paper trail, the false account statements that were supplied to clients.[86]

Madoff had a heart attack in December 2013, and reportedly had end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[87] According to CBS New York[88] and other news sources, Madoff claimed in an email to CNBC in January 2014 that he had kidney cancer, but this was unconfirmed. In a court filing from his lawyer in February 2020, it was revealed Madoff had chronic kidney failure.[89] On February 17, 2022, Madoff's sister, Sondra Weiner, and her husband, Marvin, were both found dead with gun wounds in their Boynton Beach, Florida home. The deaths of Sondra, 87, and Marvin, 90, were labeled by police as a potential murder-suicide.[90]

Government access

[edit]From 1991 to 2008, Bernie and Ruth Madoff contributed about $240,000 to federal candidates, parties, and committees, including $25,000 a year from 2005 through 2008 to the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. The committee returned $100,000 of the Madoffs' contributions to Irving Picard, the bankruptcy trustee who oversees all claims, and Senator Chuck Schumer returned almost $30,000 received from Madoff and his relatives to the trustee. Senator Chris Dodd donated $1,500 to the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, a Madoff victim.[91][92]

Members of the Madoff family have served as leaders of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), the primary securities industry organization.[93] Bernard Madoff served on the board of directors of the Securities Industry Association, a precursor of SIFMA, and was chairman of its trading committee.[94] He was a founding board member of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) subsidiary in London, the International Securities Clearing Corporation.[95][96]

Madoff's brother Peter served two terms as a member of SIFMA's board of directors. He and Andrew received awards from SIFMA in 2008 for "extraordinary leadership and service".[97][98] He resigned from the board of directors of SIFMA in December 2008, as news of the Ponzi scheme broke.[93] From 2000 to 2008, the Madoff brothers donated $56,000 directly to SIFMA, and paid additional money as sponsors of industry meetings.[99] Bernard Madoff's niece Shana Madoff was a member of the executive committee of SIFMA's Compliance & Legal Division, but resigned shortly after the arrest.[100]

Madoff's name first came up in a fraud investigation in 1992, when two people complained to the SEC about investments they made with Avellino & Bienes, the successor to his father-in-law's accounting practice. For years, Alpern and two of his colleagues, Frank Avellino and Michael Bienes, had raised money for Madoff, a practice that continued after Avellino and Bienes took over the firm in the 1970s.[101] Avellino returned the money to investors and the SEC closed the case.[102]

In 2004, Genevievette Walker-Lightfoot, a lawyer in the SEC's Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (OCIE), informed her supervisor branch chief Mark Donohue that her review of Madoff found numerous inconsistencies, and recommended further questioning. However, she was told by Donohue and his boss Eric Swanson to stop work on the Madoff investigation, send them her work results, and instead investigate the mutual fund industry. Swanson, assistant director of the SEC's OCIE,[103] had met Shana Madoff in 2003 while investigating her uncle Bernie Madoff and his firm. The investigation was concluded in 2005. In 2006, Swanson left the SEC and became engaged to Shana Madoff, and in 2007 the two married.[104][105] A spokesman for Swanson said he "did not participate in any inquiry of Bernard Madoff Securities or its affiliates while involved in a relationship" with Shana Madoff.[106]

While awaiting sentencing, Madoff met with the SEC's inspector general, H. David Kotz, who conducted an investigation into how regulators had failed to detect the fraud despite numerous red flags.[107] Madoff said he could have been caught in 2003, but that bumbling investigators had acted like "Lt. Columbo" and never asked the right questions. He said "They never even looked at my stock records," and that it "would've been easy for them to see" if they'd checked with the Depository Trust Company; "if you're looking at a Ponzi scheme, it's the first thing you do."[108]

Madoff said in the June 17, 2009, interview that SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro was a "dear friend", and SEC Commissioner Elisse Walter was a "terrific lady" whom he knew "pretty well".[109] After Madoff's arrest, the SEC was criticized for its lack of financial expertise and lack of due diligence, despite having received complaints from Harry Markopolos[110] and others for almost a decade. The SEC's inspector general, Kotz, found that since 1992, there had been six investigations of Madoff by the SEC, which were botched either through incompetent staff work or by neglecting allegations of financial experts and whistle-blowers. At least some of the SEC investigators doubted whether Madoff was even trading.[111][112][113]

Due to concerns of improper conduct by Inspector General Kotz in the Madoff investigation, Inspector General David C. Williams of the United States Postal Service was brought in to conduct an independent outside review.[114] The Williams Report questioned Kotz's work on the Madoff investigation, because Kotz was a "very good friend" of Markopolos.[115][116] Investigators were not able to determine when Kotz and Markopolos became friends. A violation of the ethics rule would have taken place if the friendship were concurrent with Kotz's investigation of Madoff.[115][117]

Investment scandal

[edit]In 1999, financial analyst Harry Markopolos had informed the SEC that he believed it was legally and mathematically impossible to achieve the gains Madoff claimed to deliver. According to Markopolos, it took him four minutes to conclude that Madoff's numbers did not add up, and another minute to suspect they were fraudulent.[118] After four hours of failed attempts to replicate Madoff's numbers, Markopolos believed he had mathematically proven Madoff was a fraud.[119] He was ignored by the SEC's Boston office in 2000 and 2001, as well as by Meaghan Cheung at the SEC's New York office in 2005 and 2007 when he presented further evidence. He has since co-authored a book with Gaytri D. Kachroo, the leader of his legal team, titled No One Would Listen. The book details the frustrating efforts he and his legal team made over a ten-year period to alert the government, the industry, and the press about Madoff's fraud.[118]

Although Madoff's wealth management business ultimately grew into a multibillion-dollar operation, none of the major derivatives firms traded with him because they did not believe his numbers were real. None of the major Wall Street firms invested with him, and several high-ranking executives at those firms suspected his operations and claims were not legitimate.[119] Others contended it was inconceivable that the growing volume of Madoff's accounts could be competently and legitimately serviced by his documented accounting/auditing firm, a three-person firm with only one active accountant.[120] The Central Bank of Ireland failed to spot Madoff's gigantic fraud when he started using Irish funds and had to supply large amounts of information, which would have been enough to enable Irish regulators to uncover the fraud much earlier than late 2008 when he was finally arrested in New York.[121][122][123]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation report and federal prosecutors' complaint says that during the first week of December 2008, Madoff confided to a senior employee, identified by Bloomberg News as one of his sons, that he said he was struggling to meet $7 billion in redemptions.[16] For years, Madoff had simply deposited investors' money in his business account at JPMorgan Chase and withdrew money from that account when they requested redemptions. He had scraped together just enough money to make a redemption payment on November 19. However, despite cash infusions from several longtime investors, by the week after Thanksgiving it was apparent that there was not enough money to even begin to meet the remaining requests. His Chase account had over $5.5 billion in mid-2008, but by late November was down to $234 million, not even a fraction of the outstanding redemptions. With banks having all stopped lending, Madoff knew he could not even begin to borrow the money he needed. On December 3, he told longtime assistant Frank DiPascali, who had overseen the fraudulent advisory business, that he was finished. On December 9, he told his brother Peter about the fraud.[101][23]

According to the sons, Madoff told Mark Madoff on the following day, December 9, that he planned to pay out $173 million in bonuses two months early.[124] Madoff said that "he had recently made profits through business operations, and that now was a good time to distribute it."[16] Mark told Andrew Madoff, and the next morning they went to their father's office and asked him how he could pay bonuses to his staff if he was having trouble paying clients. They then traveled to Madoff's apartment, where with Ruth Madoff nearby, Madoff told them he was "finished", that he had "absolutely nothing" left, and that his investment fund was "just one big lie" and "basically, a giant Ponzi scheme."[124][23]

According to their attorney, Madoff's sons then reported their father to federal authorities.[16] Madoff had intended to wind up his operations over the remainder of the week before having his sons turn him in; he directed DiPascali to use the remaining money in his business account to cash out the accounts of several family members and favored friends.[101] However, as soon as they left their father's apartment, Mark and Andrew immediately contacted a lawyer, who in turn got them in touch with federal prosecutors and the SEC.[23] On December 11, 2008, Madoff was arrested and charged with securities fraud.[18]

Madoff posted $10 million bail in December 2008 and remained under 24-hour monitoring and house arrest in his Upper East Side penthouse apartment until his guilty plea on March 12, 2009. On that date, Judge Denny Chin revoked his bail and remanded him to the Metropolitan Correctional Center pending sentencing. Chin ruled that Madoff was a flight risk because of his age, his wealth, and the prospect of spending the rest of his life in prison.[125] Prosecutors filed two asset forfeiture pleadings which include lists of valuable real and personal property as well as financial interests and entities owned or controlled by Madoff.[126]

Madoff's lawyer, Ira Sorkin, filed an appeal, which prosecutors opposed.[126] On March 20, 2009, an appellate court denied Madoff's request to be released from jail and returned to home confinement until his sentencing on June 29, 2009. On June 22, 2009, Sorkin hand-delivered a customary pre-sentencing letter to the judge requesting a sentence of 12 years, because of tables from the Social Security Administration that his life span was predicted to be 13 years.[107][127]

On June 26, 2009, Chin ordered forfeiture of $170 million in Madoff's assets. Prosecutors asked Chin to sentence Madoff to 150 years in prison.[128][129][130] Bankruptcy Trustee Irving Picard indicated that "Mr. Madoff has not provided meaningful cooperation or assistance."[131] In settlement with federal prosecutors, Madoff's wife Ruth agreed to forfeit her claim to $85 million in assets, leaving her with $2.5 million in cash.[132] The order allowed the SEC and Court appointed trustee Irving Picard to pursue Ruth Madoff's funds.[131] Massachusetts regulators also accused her of withdrawing $15 million from company-related accounts shortly before he confessed.[133]

In February 2009, Madoff reached an agreement with the SEC.[134] It was later revealed that as part of the agreement, Madoff accepted a lifetime ban from the securities industry.[135] Picard sued Madoff's sons, Mark and Andrew, his brother Peter, and Peter's daughter, Shana, for negligence and breach of fiduciary duty, for $198 million. The defendants had received over $80 million in compensation since 2001.[136][137]

Mechanics of the fraud

[edit]According to an SEC indictment, office workers Annette Bongiorno and Joann Crupi created false trading reports based on the returns that Madoff ordered for each customer.[138] For example, when Madoff determined a customer's return, one of the back office workers would enter a false trade report with a previous date and then enter a false closing trade in the amount required to produce the required profit, according to the indictment. Prosecutors allege that Bongiorno used a computer program specially designed to backdate trades and manipulate account statements.[139] They quote her as writing to a manager in the early 1990s, "I need the ability to give any settlement date I want."[138] In some cases, returns were allegedly determined before the account was even opened.[139]

On a daily basis, DiPascali and his team on the 17th floor of the Lipstick Building, where the scam was based (Madoff's brokerage was based on the 19th floor, while the main entrance and conference room were on the 18th floor), watched the closing price of the S&P 100. They then picked the best-performing stocks and used them to create bogus "baskets" of stocks as the basis for false trading records, which Madoff claimed were generated from his supposed "split-strike conversion" strategy, in which he bought blue-chip stocks and took options contracts[clarification needed] on them. They frequently made their "trades" at a stock's monthly high or low, resulting in the high "returns" that they touted to customers. On occasion, they slipped up and dated trades as taking place on weekends and federal holidays, though this was never caught.[23]

Over the years, Madoff admonished his investors to keep quiet about their relationship with him. This was because he was well aware of the finite limits that existed for a legitimate split-strike conversion. He knew that if the amount he "managed" became known, investors would question whether he could trade on the scale he claimed without the market reacting to his activity, or whether there were enough options to hedge his stock purchases.[101]

As early as 2001, Harry Markopolos discovered that in order for Madoff's strategy to be possible, he would have had to buy more options on the Chicago Board Options Exchange than actually existed.[118] Additionally, at least one hedge-fund manager, Suzanne Murphy, revealed that she balked at investing with Madoff because she did not believe there was enough volume to support his purported trading activity.[23]

Madoff admitted during his March 2009 guilty plea that the essence of his scheme was to deposit client money into a bank account, rather than invest it and generate steady returns as clients had believed. When clients wanted their money, "I used the money in the Chase Manhattan bank account that belonged to them or other clients to pay the requested funds," he told the court.[140][141]

Madoff maintained that he began his fraud in the early 1990s, though prosecutors believed it was underway as early as the 1980s. DiPascali, for instance, told prosecutors that he knew at some point in the late 1980s or early 1990s that the investment advisory business was a sham.[101] An investigator charged with reconstructing Madoff's scheme believes that the fraud was well under way as early as 1964. Reportedly, Madoff told an acquaintance soon after his arrest that the fraud began "almost immediately" after his firm opened its doors. Bongiorno, who spent over 40 years with Madoff–longer than anyone except Ruth and Peter–told investigators that she was doing "the same things she was doing in 2008" when she first joined the firm.[23]

Affinity fraud

[edit]Madoff targeted wealthy American Jewish communities, using his in-group status to obtain investments from Jewish individuals and institutions. Affected Jewish charitable organizations considered victims of this affinity fraud include Hadassah, the Women's Zionist Organization of America, the Elie Wiesel Foundation and Steven Spielberg's Wunderkinder Foundation. Jewish federations and hospitals lost millions of dollars, forcing some organizations to close. The Lappin Foundation, for instance, was forced to close temporarily because it had invested its funds with Madoff.[142]

Size of loss to investors

[edit]David Sheehan, chief counsel to trustee Picard, stated on September 27, 2009, that about $36 billion was invested into the scam, returning $18 billion to investors, with $18 billion missing. About half of Madoff's investors were "net winners", earning more than their investment. The withdrawal amounts in the final six years were subject to "clawback" (return of money) lawsuits.[22]

In a May 4, 2011, statement, trustee Picard said that the total amount owed to customers (with some adjustments) was $57 billion, of which $17.3 billion was actually invested by customers. $7.6 billion has been recovered, but pending lawsuits, only $2.6 billion was available to repay victims.[143][144] The Internal Revenue Service ruled that investors' capital losses in this and other fraudulent investment schemes would be treated as business losses, thereby allowing the victims to claim a tax deduction for such losses.[145][146]

The size of the fraud was stated as $65 billion early in the investigation. Former SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt estimated the actual net fraud to be between $10 and $17 billion.[147] One difference between the estimates results from different methods of calculation. One method calculates losses as the total amount that victims thought they were owed, but will never receive. The smaller estimates are arrived at by subtracting the total cash received from the scheme from the total cash paid into the scheme, after excluding from the calculation persons accused of collaborating with the scheme, persons who invested through "feeder funds", and anyone who received more cash from the scheme than they paid in. Erin Arvedlund, who publicly questioned Madoff's reported investment performance in 2001, stated that the actual amount of the fraud might never be known, but was likely between $12 and $20 billion.[148][149][150]

Jeffry Picower, rather than Madoff, appears to have been the largest beneficiary of Madoff's Ponzi scheme, and his estate settled the claims against it for $7.2 billion.[151][152] Entities and individuals affiliated with Fred Wilpon and Saul Katz received $300 million in respect of investments in the scheme. Wilpon and Katz "categorically reject[ed]" the charge that they "ignored warning signs" about Madoff's fraud.[153] On November 9, 2017, the U.S. government announced that it would begin paying out $772.5 million from the Madoff Victim Fund to more than 24,000 victims of the Ponzi scheme.[154] The Madoff Recovery Initiative reported $14.418 billion in total recoveries and settlement agreements.[25]

Plea, sentencing, and prison life

[edit]On March 12, 2009, Madoff pleaded guilty to 11 federal felonies, including securities fraud, wire fraud, mail fraud, money laundering, making false statements, perjury, theft from an employee benefit plan, and making false filings with the SEC. The plea was the response to a criminal complaint filed two days earlier, which stated that over the past 20 years, Madoff had defrauded his clients of almost $65 billion in the largest Ponzi scheme in history. Madoff insisted he was solely responsible for the fraud.[111][155] He pleaded guilty to all charges without a plea bargain; it has been speculated that he did this instead of cooperating with the authorities in order to avoid naming any associates and co-conspirators in the scheme.[156][157]

In November 2009, David G. Friehling, Madoff's accounting front man and auditor, pleaded guilty to securities fraud, investment adviser fraud, making false filings to the SEC, and obstructing the Internal Revenue Service. He admitted to merely rubber-stamping Madoff's filings rather than auditing them.[158] Friehling extensively cooperated with federal prosecutors and testified at the trials of five former Madoff employees, all of whom were convicted and sentenced to between 2 and a half and 10 years in prison. Although he could have been sentenced to more than 100 years in prison, because of his cooperation, Friehling was sentenced in May 2015 to one year of home detention and one year of supervised release.[159] His involvement made the Madoff scheme by far the largest accounting fraud in history, dwarfing the $11 billion accounting fraud masterminded by Bernard Ebbers in the WorldCom scandal. Madoff's right-hand man and financial chief, Frank DiPascali, pleaded guilty to 10 federal charges in 2009 and (like Friehling) testified for the government at the trial of five former colleagues, all of whom were convicted. DiPascali faced a sentence of up to 125 years, but he died of lung cancer in May 2015, before he could be sentenced.[160][161]

In his plea allocution, Madoff stated he began his Ponzi scheme in 1991. He admitted he had never made any legitimate investments with his clients' money during this time. Instead, he said, he simply deposited the money into his personal business account at Chase Manhattan Bank. When his customers asked for withdrawals, he paid them out of the Chase account—a classic "robbing Peter to pay Paul" scenario. Chase and its successor, JPMorgan Chase, may have earned as much as $483 million from his bank account.[162][163] He was committed to satisfying his clients' expectations of high returns, despite an economic recession. He admitted to false trading activities masked by foreign transfers and false SEC filings. He stated that he always intended to resume legitimate trading activity, but it proved "difficult, and ultimately impossible" to reconcile his client accounts. In the end, he said, he realized that his scam would eventually be exposed.[125][164]

On June 29, 2009, Judge Chin sentenced him to the maximum sentence of 150 years in federal prison.[26][165] His lawyers initially asked the judge to impose a sentence of 7 years, and later requested that the sentence be 12 years, because of Madoff's advanced age of 71 and his limited life expectancy.[166] Madoff apologized to his victims, saying

I have left a legacy of shame, as some of my victims have pointed out, to my family and my grandchildren. This was something I will live in for the rest of my life. I'm sorry. I know that doesn't help you.

Judge Chin had not received any mitigating factor letters from friends or family testifying to Madoff's good deeds. "The absence of such support was telling," he said.[167] Judge Chin also said that Madoff had not been forthcoming about his crimes. "I have a sense Mr. Madoff has not done all that he could do or told all that he knows," said Chin, calling the fraud "extraordinarily evil", "unprecedented", and "staggering", and that the sentence would deter others from committing similar frauds.[168] Judge Chin also agreed with prosecutors' contention that the fraud began at some point in the 1980s. He also noted that Madoff's crimes were "off the charts", since federal sentencing guidelines for fraud only go up to $400 million in losses.[169]

Ruth did not attend court but issued a statement, saying: "I am breaking my silence now because my reluctance to speak has been interpreted as indifference or lack of sympathy for the victims of my husband Bernie's crime, which was exactly the opposite of the truth. I am embarrassed and ashamed. Like everyone else, I feel betrayed and confused. The man who committed this horrible fraud was not the man whom I have known for all these years."[170][171]

Incarceration

[edit]

Madoff's attorney asked the judge to recommend that the Federal Bureau of Prisons place Madoff in the Federal Correctional Institution, Otisville, which was located 70 miles (110 km) from Manhattan. The judge, however, only recommended that Madoff be sent to a facility in the Northeast United States. He was transferred to the Federal Correctional Institution Butner Medium near Butner, North Carolina, about 45 miles (72 km) northwest of Raleigh; he was Bureau of Prisons Register #61727-054.[172][173] Jeff Gammage of The Philadelphia Inquirer said, in regards to his prison assignment, "Madoff's heavy sentence likely determined his fate."[174]

Madoff's projected release date was January 31, 2137.[173][175] The release date, described as "academic" in Madoff's case because he would have to live to the age of 198, reflects a reduction for good behavior.[176] On October 13, 2009, it was reported that Madoff experienced his first prison yard fight with another inmate, also a senior citizen.[177] When he began his sentence, Madoff's stress levels were so severe that he broke out in hives and other skin maladies soon after.[178]

On December 18, 2009, Madoff was moved to Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and was treated for several facial injuries. A former inmate later claimed that the injuries were received during an alleged altercation with another inmate.[179] Other news reports described Madoff's injuries as more serious and including "facial fractures, broken ribs, and a collapsed lung".[178][180] The Federal Bureau of Prisons said Madoff signed an affidavit on December 24, 2009, which indicated that he had not been assaulted and that he had been admitted to the hospital for hypertension.[181] In his letter to his daughter-in-law, Madoff said that he was being treated in prison like a "Mafia don".

They call me either Uncle Bernie or Mr. Madoff. I can't walk anywhere without someone shouting their greetings and encouragement, to keep my spirit up. It's really quite sweet, how concerned everyone was about my well being, including the staff ... It's much safer here than walking the streets of New York.[182]

After an inmate slapped Madoff because he had changed the channel on the TV, it was reported that Madoff befriended Carmine Persico, boss of the Colombo crime family since 1973, one of New York's five American Mafia families.[183] It was believed Persico had intimidated the inmate who slapped Madoff in the face.[184] On July 29, 2019, Madoff asked Donald Trump for a reduced sentence or pardon, to which the White House and Donald Trump made no comment.[185] In February 2020, his lawyer filed for compassionate release from prison on the claim that he had chronic kidney failure, a terminal illness leaving him less than 18 months to live, and that the COVID-19 pandemic further threatened his life.[186] He was hospitalized for this condition in December 2019.[89][187] The request was denied due to the severity of Madoff's crimes.[188][189][190][191]

Death

[edit]Madoff died of hypertension, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease at the age of 82 in Federal Medical Center, Butner, a federal prison for inmates with special health needs near Butner, North Carolina, on April 14, 2021.[192][193][194] He was cremated in Durham, North Carolina.[195]

Philanthropy and other activities

[edit]Madoff was a prominent philanthropist,[18][69] who served on boards of nonprofit institutions, many of which entrusted his firm with their endowments.[18][69] The collapse and freeze of his personal assets and those of his firm affected businesses, charities, and foundations around the world, including the Chais Family Foundation,[196] the Robert I. Lappin Charitable Foundation, the Picower Foundation, and the JEHT Foundation which were forced to close.[18][197] Madoff donated approximately $6 million to lymphoma research after his son Andrew was diagnosed with the disease.[198] He and his wife gave over $230,000 to political causes since 1991, with the bulk going to the Democratic Party.[199]

Madoff served as the chairman of the board of directors of the Sy Syms School of Business at Yeshiva University, and as treasurer of its board of trustees.[69] He resigned his position at Yeshiva University after his arrest.[197] Madoff also served on the board of New York City Center, a member of New York City's Cultural Institutions Group (CIG).[200] He served on the executive council of the Wall Street division of the UJA Foundation of New York which declined to invest funds with him because of the conflict of interest.[201]

Madoff undertook charity work for the Gift of Life Bone Marrow Foundation and made philanthropic gifts through the Madoff Family Foundation, a $19 million private foundation, which he managed along with his wife.[18] They also donated money to hospitals and theaters.[69] The foundation also contributed to many educational, cultural, and health charities, including those later forced to close because of Madoff's fraud.[202] After Madoff's arrest, the assets of the Madoff Family Foundation were frozen by a federal court.[18]

In the media

[edit]- On May 12, 2009, PBS Frontline aired The Madoff Affair, and subsequently ShopPBS made DVD videos of the show and transcripts available for purchase by the public at large.

- In season 7 of Curb Your Enthusiasm, aired in 2009, the character George Costanza (from Seinfeld) loses all of the money he made from an app called iToilet by investing with Madoff.

- Imagining Madoff was a 2010 play by Deb Margolin that tells the story of an imagined encounter between Madoff and his victims. The play generated controversy when Elie Wiesel, originally portrayed as a character in the play, threatened legal action, forcing Margolin to substitute a fictional character, "Solomon Galkin". The play was nominated for a 2012 Helen Hayes Award.

- A documentary, Chasing Madoff, describing Harry Markopolos' efforts to unmask the fraud, was released in August 2011.

- Woody Allen's 2013 film Blue Jasmine portrays a fictional couple involved in a similar scandal. Allen said that the Madoff scandal was the inspiration for the film.[203]

- In God We Trust (2013), a documentary about Eleanor Squillari, Madoff's secretary for 25 years and her search for the truth about the fraud (The Halcyon Company).[204]

- Madoff was played by Robert De Niro in the May 2017 HBO film The Wizard of Lies, based on the best-selling book by Diana B. Henriques. Michelle Pfeiffer plays Ruth Madoff in the film, which was released on May 20, 2017.

- Madoff, a miniseries by ABC starring Richard Dreyfuss and Blythe Danner as Bernard and Ruth Madoff, aired on February 3 and 4, 2016.[205][206]

- "Ponzi Super Nova", an episode of the podcast Radiolab released February 10, 2017, in which Madoff was interviewed over prison phone.[207]

- Chevelle's song "Face to the Floor", as described by the band, was a "pissed off, angry" song about people who got taken by the Ponzi scheme that Bernie Madoff had for all those years."[208]

- The heroine of Elin Hilderbrand's novel, Silver Girl, published in 2011 by Back Bay Books, was the wife of a Madoff-like schemer.[209]

- Cristina Alger's novel, The Darlings, published in 2012 by Pamela Dorman Books, features a wealthy family with a Madoff-like patriarch.[210]

- The action of James Grippando's thriller, Need You Now, published in 2012 by HarperCollins, was set in motion by the suicide of the Bernie Madoff-like Ponzi schemer Abe Cushman.[211]

- The protagonist of Elinor Lipman's novel, The View from Penthouse B, published in 2013 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, loses her divorce settlement by investing it with Bernie Madoff.[212]

- Randy Susan Meyers's novel, The Widow of Wall Street, published in 2017 by Atria Books, was a fictionalized account of the Madoff Ponzi scheme from the wife's point of view.[213]

- Emily St. John Mandel's novel, The Glass Hotel, published in 2020 by Alfred A. Knopf, includes a character named Jonathan Alkaitis, who was based on Madoff.[214][215]

- A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff (2021), a docudrama created by musician/poet Alicia Jo Rabins and directed by Alicia J. Rose, tells the story of Madoff and the system that allowed him to function for decades through the eyes of Rabins, who watches the financial crash from her 9th floor studio in an abandoned office building on Wall Street.

- In January 2023, Netflix released a four-part documentary series, Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street, produced by RadicalMedia and directed by Joe Berlinger.[216]

See also

[edit]- Allen Stanford

- Financial crisis of 2007–2008

- List of investors in Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities

- Madoff investment scandal

- Participants in the Madoff investment scandal

- Recovery of funds from the Madoff investment scandal

- White-collar crime

References

[edit]- ^ "Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, LLC (BMIS)". madoffinvestmentsecurities.com. February 26, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ "Voice of America pronunciation guide". Voice of America. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ Graybow, Martha (March 11, 2009). "US Prosecutors updated the size of Madoff's scheme from $50 billion to $64 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009.

- ^ a b "Wife Says She and Madoff Tried Suicide". The New York Times. Reuters. October 26, 2011. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018.

- ^ "Ex-Nasdaq chair arrested for securities fraud". CNN. December 12, 2008. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

- ^ Langer, Emily (April 14, 2021). "Bernard Madoff, mastermind of vast Wall Street Ponzi scheme, dies at 82". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Madoff Case: A Timeline". The Wall Street Journal. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015.

- ^ Henriques, Diana (January 13, 2009). "New Description of Timing on Madoff's Confession". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Lieberman, David; Gogoi, Pallavi; Howard, Theresa; McCoy, Kevin; Krantz, Matt (December 15, 2008). "Investors remain amazed over Madoff's sudden downfall". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008.

- ^ "Peter Madoff Sentenced to 10 Years for Role in Ponzi Scheme". NBC News. December 20, 2012. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Cornell, Irene (December 11, 2010). "Officials: Bernie Madoff's Son Mark Madoff Found Dead Of Apparent Suicide In Soho Apartment". CBS News. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c Candiotti, Susan (December 11, 2010). "Madoff son found dead of apparent suicide". CNN. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Sean; Rothfeld, Michael; Eder, Steve; Bray, Chad (December 12, 2010). "Madoff's Son Is Found Dead in Apparent Suicide". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Neumeister, Larry; Hays, Tom (December 13, 2010). "Madoff son's suicide follows battle with trustee". NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff's Surviving Son Andrew Dies of Lymphoma". NBC News. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Voreacos, David; Glovin, David (December 13, 2008). "Madoff Confessed $50 Billion Fraud Before FBI Arrest". National Post. Bloomberg News.

- ^ "SEC: Complaint SEC against Madoff and BMIS LLC" (PDF). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. December 11, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Appelbaum, Binyamin; Hilzenrath, David S.; Paley, Amit R. (December 13, 2008). "All Just One Big Lie". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010.

- ^ McCool, Grant (November 21, 2011). "Ex-Madoff trader admits faking records since '70s". Reuters.

- ^ Rushe, Dominic (November 18, 2011). "Bernard Madoff fraud 'began 20 years earlier than admitted'". The Guardian.

- ^ Riley, Charles (October 1, 2012). "Prosecutors: Madoff fraud started in 1970s". CNN.

- ^ a b c Safer, Morley (September 27, 2009). "The Madoff Scam: Meet The Liquidator". 60 Minutes. CBS News. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ross, Brian (2015). The Madoff Chronicles. Kingswell. ISBN 9781401310295.

- ^ McCool, Grant; Graybow, Martha (March 13, 2009). "Madoff pleads guilty, was jailed for $65 billion fraud". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Madoff Recovery Initiative". Madoff (SIPA) Trustee. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Bernard Madoff gets 150 years behind bars for fraud scheme". CBC News. June 29, 2009. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009.

- ^ Henriques, Diana B. (June 29, 2009). "Madoff Sentenced to 150 Years for Ponzi Scheme". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (June 29, 2009). "Madoff sentenced to 150 years". CNN.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (June 29, 2009). "Madoff Sentenced To Maximum 150 Years In Prison". NPR.

- ^ "AP source: Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff dies in prison". Associated Press. April 14, 2021. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Marty; Cohn, Scott (April 14, 2021). "Bernie Madoff, mastermind of the nation's biggest investment fraud, dies at 82". CNBC.

- ^ a b "Disgraced financier, Ponzi scheme architect Bernie Madoff dies in prison". The Jerusalem Post. Reuters. April 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Rothfeld, Michael; Baer, Justin (April 14, 2021). "Bernie Madoff Dead at 82; Disgraced Investor Ran Biggest Ponzi Scheme in History". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Varchaver, Nicholas (January 16, 2009). "Madoff's mother tangled with the feds". CNN. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

- ^ Lauria, Joe (March 22, 2009). "Life inside the weird world of Bernard Madoff". The Times. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011.

- ^ "Bernard Madoff Fast Facts". CNN. April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff dies in prison at 82". Associated Press. April 14, 2021. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021.

- ^ Bandler, James; Varchaver, Nicholas (April 24, 2009). "How Bernie Mandoff pulled off his massive swindle". CNN. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009.

- ^ "A look at the Madoffs two years after Bernie's scandal unfolded". New York Post. December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Oppenheimer, Jerry (2009). Madoff with the Money. Wiley. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-470-50498-7. "Ruth, who grew up in Laurelton, Queens, with Bernie became his steady at Far Rockaway High School. She had attributes that intrigued Bernie: She had a 'shiksa' look, but was Jewish; she was social and outgoing; she had a shrewd accountant father, and she was a whiz at one particular subject – math – all the right stuff for a future Master of the Universe in the gilded canyons of Wall Street. Married in 1959, Bernie would later cheat on her like he cheated his clients."

- ^ Carney, John (December 22, 2008). "The Education of Bernie Madoff: The High School Years". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012.

- ^ Salkin, Allen (January 18, 2009). "Bernie Madoff, Frat Brother". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Reske, Henry J. (March 12, 2009). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Bernard Madoff". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Creswell, Julie; Thomas, Landon Jr. (January 24, 2009). "The Talented Mr. Madoff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Madoff files: Bernie's billions". The Independent. London. March 29, 2009. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009.

- ^ "Madoff's tactics date to 1960s, when father-in-law was recruiter". The Jerusalem Post. February 1, 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c de la Merced, Michael J. (December 24, 2008). "Effort Under Way to Sell Madoff Unit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Weiner, Eric J. (2007). What Goes Up: The Uncensored History of Modern Wall Street as Told by the Bankers, Brokers, CEOs, and Scoundrels who Made it Happen. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 188–192. ISBN 978-0-316-92966-0. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016.

- ^ "Madoff Securities International Ltd v Raven & Ors (2013) EWHC 3147 (Comm) (18 October 2013)". British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII). October 18, 2013. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Another Stab AtThe Third Market: Madoff's Brave New Trading World". Traders Magazine. August 31, 1999.

- ^ "SEC Charges Bernard L. Madoff for Multi-Billion Dollar Ponzi Scheme (2008–293)" (Press release). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. December 11, 2008. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008.

- ^ Wilhelm, William J.; Downing, Joseph D. (2001). Information Markets: What Businesses Can Learn from Financial Innovation. Harvard Business Press. p. 153. ISBN 1-57851-278-6.

- ^ Princeton University Undergraduate Task Force (January 2005). "The Regulation of Publicly Traded Securities" (PDF). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. p. 58. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ^ Ferrell, Allen (2001). "A Proposal for Solving the 'Payment for Order Flow' Problem 74 S.Cal.L.Rev. 1027" (PDF). Harvard University. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 26, 2013.

- ^ Battalio, Robert H.; Loughran, Tim (January 15, 2007). "Does Payment for Order Flow to Your Broker Help or Hurt You?" (PDF). Notre Dame University. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2017.

- ^ a b McMillan, Alex (May 29, 2000). "Q&A: Madoff Talks Trading". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019.

- ^ Henriques, Diana B. (January 13, 2009). "New Description of Timing on Madoff's Confession". The New York Times.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff's bride grew up in a Laurelton home". qchron.com. July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "The Trials of Ruth Madoff". People. February 21, 2011. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Have pity on Ruth Madoff". CNN. November 14, 2009. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Seal, Mark (April 2009). "Madoff's World". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009.

- ^ Lambiet (December 12, 2008). "Bernie Madoff's arrest sent tremors into Palm Beach". Palm Beach Daily. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ "A Charmed Life, a Tragic Death". People. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on April 18, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

Today would have been Mark's 47th birthday! I will never forget the kind and fun loving person he was. This will always be a difficult day of the year for me.

- ^ Henriques, Diana B. (September 3, 2014). "Andrew Madoff Son of Convicted Fraudster Dies at 48". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Tale of the Madoff Sons". New York Magazine. June 3, 2009. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "Mark Madoff in 'The Madoff Chronicles'". MSNBC. December 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "The Trials of Ruth Madoff". People. February 21, 2011. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Feuer, Alan; Haughney, Christine (December 13, 2008). "Standing Accused: A Pillar of Finance and Charity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff's sons and brother investigated". Thefirstpost.co.uk. February 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Government's Affirmation in Opposition To Madoff's Motion for a stay and reinstatement of bail pending sentencing" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2009.

- ^ Lucchetti, Aaron; Lauricella, Tom (March 29, 2009). "Sons' Roles in Spotlight". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016.

- ^ Efrati, Amir (February 11, 2010). "Prosecutors Set Sights on Madoff Kin". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016.

- ^ Paynter, Sarah (April 14, 2021). "See inside the Hamptons home once owned by Bernie Madoff". New York Post.

- ^ Jagger, Suzy (December 18, 2008). "Bernard Madoff: the 'most hated man in New York' seeks $3m for bail". The Times. London. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Frank, Robert; Lattman, Peter; Searcey, Dionne; Lucucchetti, Aaron (December 13, 2008). "Fund Fraud Hits Big Names; Madoff's Clients Included Mets Owner, GMAC Chairman, Country-Club Recruits". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015.

- ^ Gross, Daniel (January 2, 2009). "How Madoff Fleeced the Palm Beach Elite". Newsweek.

- ^ Loney, Jim (December 19, 2008). "Madoff scandal stuns Palm Beach Jewish community". Reuters.

- ^ Hofheinz, Darrell (October 20, 2015). "Buyer of Madoff lakefront house resells it for $9M". Palm Beach Daily News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Destefano, Anthony (August 14, 2009). "Proposals sought from brokers for sale of Madoff homes". Newsday. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009.

- ^ "Bernard Madoff's personal property to be auctioned". Deccan Herald. Boston. October 20, 2009. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010.

- ^ Henriques, Diana; Strom, Stephanie (August 13, 2009). "Woman Tells of Affair With Madoff in New Book". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ "ABC News". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ McCool, Grant (March 13, 2009). "Madoff to appeal bail, net worth revealed". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 20, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Fraudster Bernard Madoff and wife 'attempted suicide'". BBC News. October 26, 2011. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Hilzenrath, David S. (November 22, 2011). "Former Madoff trader David Kugel pleads guilty to fraud". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff health crises". Huffington Post. January 22, 2014. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Report: Madoff Battling Cancer, Recovering From Heart Attack". January 22, 2014. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Baer, Justin (February 5, 2020). "Bernie Madoff Says He's Dying, Requests Early Release From Prison". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020.

- ^ Timsit, Annabelle (February 21, 2022). "Bernie Madoff's sister and her husband found dead in apparent murder-suicide, Florida police say". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Becker, Bernie (March 26, 2009). "Money From Madoff was Rerouted". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009.

- ^ O'Brien, Michael (March 28, 2009). "DSCC donates Madoff money to his victims' fund". The Hill.

- ^ a b Williamson, Elizabeth; Scannell, Kara (December 18, 2008). "Family Filled Posts at Industry Groups". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015.

- ^ Ross, Brian (2009). The Madoff Chronicles: Inside the Secret World of Bernie and Ruth. HarperCollins. ISBN 9781401394929. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016.

- ^ Strober, Deborah Hart; Strober, Gerald; Strober, Gerald S. (2009). Catastrophe: The Story of Bernard L. Madoff, the Man Who Swindled the World. Phoenix Books. ISBN 9781597776400. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016.

- ^ Schwartz, Robert A.; Byrne, John Aidan; Colaninno, Antoinette (2005). Coping With Institutional Order Flow. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 9781402075117. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ Rockefeller, J.D. (2016). The Bernie Madoff Ponzi Scheme.

- ^ "Andrew Madoff Dead: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy. September 3, 2014.

- ^ Williamson, Elizabeth (December 22, 2008). "Shana Madoff's Ties to Uncle Probed". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

- ^ Barlyn, Suzanne (December 23, 2008). "Madoff Case Raises Compliance Questions". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b c d e Henriques, Diana (2011). The Wizard of Lies. Times Books. ISBN 978-0805091342.

- ^ Berenson, Alex (January 16, 2009). "'92 Ponzi Case Missed Signals About Madoff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017.

- ^ Goldfarb, Zachary A. (July 2, 2009). "Staffer at SEC Had Warned Of Madoff; Lawyer Raised Alarm, Then Was Pointed Elsewhere". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017.

- ^ David Kotz, H. (2009). Investigation of Failure of the SEC to Uncover Bernard Madoff's Ponzi Scheme... Diane. ISBN 9781437921861. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (December 16, 2008). "Unlikely Player Pulled Into Madoff Swirl". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017.

- ^ Ross, Bryan; Rhee, Joseph (December 16, 2008). "SEC Official Married into Madoff Family". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Kouwe, Zachery; Edmonston, Peter (June 23, 2009). "Madoff Lawyers Seek Leniency in Sentencing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ Gendar, Alison (October 31, 2009). "Bernie Madoff baffled by SEC blunders; compares agency's bumbling actions to Lt. Colombo". Daily News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009.

- ^ Gendar, Alison (October 31, 2009). "Bernie Madoff baffled by SEC blunders; compares agency's bumbling actions to Lt. Colombo". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2009.

- ^ 60 Minutes Archive: The man who figured out Madoff's Ponzi scheme. 60 Minutes. April 14, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Hipwell, Deirdre (December 12, 2008). "Wall Street legend Bernard Madoff arrested over '$50 billion Ponzi scheme'". The Times. London. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Report of Investigation Executive Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Investigations of Madoff Fraud Allegations, Part 1". United States House Committee on Financial Services. C-Span. February 4, 2009. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.

- ^ Schmidt, Robert; Gallu, Joshua (January 25, 2013). "SEC Said to Back Hire of U.S. Capitol Police Inspector General". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Robert; Gallu, Joshua (October 26, 2012). "Former SEC Watchdog Kotz Violated Ethics Rules, Review Finds". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013.

- ^ "David Kotz, Ex-SEC Inspector General, May Have Had Conflicts Of Interest". HuffPost. Reuters. October 5, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- ^ Lynch, Sarah N. (November 15, 2012). "David Weber Lawsuit: Ex-SEC Investigator Accused Of Wanting To Carry A Gun At Work, Suing For $20 Million". HuffPost. Reuters. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c Markopolos, Harry (2010). No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-55373-2.

- ^ a b "The Man Who Figured Out Madoff's Scheme". CBS News. February 27, 2009. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Jim (December 18, 2008). "Madoff's financial empire audited by tiny firm: one guy". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2010 – via Seattle Times.

- ^ I4U News. "Bernard Madoff". Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Today in the press". Taiwan Sun. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Leidig, Michael. Pyramid Games: Bernie Madoff and his Willing Disciples. Medusa Publishing. pp. 287–311. ISBN 9780957619142.

- ^ a b Margolick, David (June 15, 2009). "The Madoff Chronicles, Part III: Did the Sons Know". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009.

- ^ a b "Transcript of Madoff guilty plea hearing" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "Bail Pending Sentencing" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Madoff Letter Seeking Leniency". Scribd.com. February 18, 2010. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Government's Sentencing Memorandum 06/26/2009" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Madoff to Forfeit $170 Billion In Assets Ahead of Sentencing". The Washington Post. June 27, 2009. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ Henriques, Diana B. (June 26, 2009). "Prosecutors propose 150-year sentence for Madoff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Efrati, Amir; Frank, Robert (June 28, 2009). "Madoff's Wife Cedes Asset Claim". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ Arends, Brent (June 29, 2009). "Ruth Faces Living Off a Scant $2.5 Million". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ "Madoff's wife crying all the way to the bank". Digital Journal. June 30, 2009. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ Jones, Ashby (February 9, 2009). "Madoff Makes Peace with the SEC, Amount of Fine TBD". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 16, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "SEC: Madoff Banned From Working Again". CBS News. June 16, 2009. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ Safer, Morley (September 27, 2009). "The Madoff Scam: Meet The Liquidator". 60 Minutes. CBS News. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 29, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ "Trustee: Madoff firm was family's piggy bank". NBC News. Associated Press. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on December 22, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Hays, Tom (November 18, 2010). "2 Madoff employees charged with helping former boss' scam". Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "SEC Complaint: Annette Bongiorno" (PDF). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. November 17, 2010.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (December 2, 2010). "Madoff trustee sues JPMorgan for $6.4 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Text Of Bernard Madoff's Court Statement". NPR. March 12, 2009.

- ^ "Madoff's Victims". The Wall Street Journal. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009.

- ^ "Madoff Trustee Readies First Payout for Investors". The New York Times. Bloomberg News. May 4, 2011.

- ^ Rooney, Ben (May 4, 2011). "Madoff victims could soon start getting funds". CNN.

- ^ Browning, Lynnley (March 17, 2009). "I.R.S. Plans a Deduction for Madoff Victims". The New York Times.

- ^ Lankford, Kimberly (March 25, 2009). "Tax Write-Off for Madoff Victims". Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

- ^ Hays, Tom; Neumeister, Larry; Shamir, Shlomo (March 6, 2009). "Extent of Madoff fraud now estimated at far below $50b". Haaretz. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ Arvedlund, Erin E. (May 7, 2001). "Don't Ask, Don't Tell – Bernie Madoff was so secretive, he even asks investors to keep mum". Barron's. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- ^ Arvedlund, Erin (2009). Too Good to Be True: The Rise and Fall of Bernie Madoff. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59184-287-3.

- ^ Arvedlund, Erin (2009). Madoff, The Man who stole $65 Billion. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-141-04546-7.

- ^ Bernstein, Jake (June 28, 2009). "Madoff may not have benefited most in scam Client Jeffry Picower allegedly withdrew $5.1 billion from accounts". Pro Publica. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Healy, Beth; Ross, Casey (December 18, 2010). "Picower estate adds $7.2b to Madoff fund". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 21, 2010. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Bray, Chad (February 4, 2011). "Madoff Trustee: Mets Owners Ignored Ponzi Warning Signs". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Disis, Jill. "Madoff victims set to receive $772 million payout". CNN. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017.

- ^ Bray, Chad (March 12, 2009). "Madoff Pleads Guilty to Massive Fraud". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ Glovin, David; Larson, Erik; Voreacos, David (March 10, 2009). "Madoff to Plead Guilty in Largest US Ponzi Scheme". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ "Bernard Madoff Will Plead Guilty to 11 Charges in Financial Fraud Case, Faces 150 Years in Prison". Fox News. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on March 11, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ Dienst, Jonathan (October 30, 2009). "Madoff Accountant Set to Make a Deal". NBC New York. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Goldstein, Matthew (May 29, 2015). "Madoff Accountant Avoids Prison Term". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 26, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Larson, Erik; DiPascali, Frank (May 10, 2015). "Madoff Deputy Who Aided U.S., Dies at 58". Bloomberg Business. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Yang, Stephanie (May 11, 2015). "Former Madoff Aide Frank DiPascali Dies at Age 58 of Lung Cancer". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Ishmael, Stacy-Marie (August 26, 2009). "How much money did JPMorgan make on Madoff?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- ^ Davis, Lou; Wilson, Linus (January 28, 2010). "Estimating JP Morgan Chase's Profits from the Madoff Deposits". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 1460706.

- ^ "Plea Allocution of Bernard Madoff (US v. Bernard Madoff)". FindLaw. March 12, 2009. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ "Fraudster Madoff gets 150 years". BBC News. June 29, 2009. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ "USA v Beranrd L. Madoff" (PDF). Justice.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Zambito, Thomas; Martinez, Jose; Siemaszko, Corky (June 29, 2009). "Bye, Bye Bernie: Ponzi king Madoff sentenced to 150 years". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ Zuckerman, Gregory; Jones, Ashby; Copeland, Robert; Bray, Chad (June 30, 2009). "'Evil' Madoff Gets 150 Years in Epic Fraud". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ Murakami Tse, Tomoeh (June 30, 2009). "Madoff Sentenced to 150 Years Calling Ponzi Scheme 'Evil,' Judge Orders Maximum Term". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ "Statement of Ruth Madoff" (PDF). ABC News.

- ^ "Ruth: 'I Feel Betrayed and Confused'". New York Post. June 30, 2009.

- ^ Chuchmach, Megan; Esposito, Richard; Katersky, Aaron (July 14, 2009). "Bernie Madoff 'Hit the Inmate Lottery' with Butner Prison, Consultant Says". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "Bernard Madoff profile". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Gammage, Jeff (August 4, 2009). "Fumo's future in agency's hands". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Kouwe, Zachery (July 14, 2009). "Madoff Arrives at Federal Prison in North Carolina". The New York Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ "Madoff moved to prison in Atlanta -US prison record". Reuters. July 14, 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ Calder, Rich (October 13, 2009). "Bernie's bruising battle – over stocks!". New York Post. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Mangan, Dan (June 21, 2010). "Madoff's hidden booty". New York Post. Archived from the original on June 23, 2010.

- ^ Searcey, Dionne; Efrati, Amir (March 10, 2010). "Madoff Beaten in Prison: Ponzi Schemer Was Assaulted by Another Inmate in December; Officials Deny Incident'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff Brutally Beaten In Prison". YouTube. December 24, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Sandholm, Drew (March 18, 2010). "Prison Disputes Madoff Beating Story". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Rhee, Joseph (October 20, 2011). "'Like a Mafia Don': Bernie Madoff's Boastful Letter to Angry Daughter-in-Law". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Andrew (June 7, 2010). "Bernie Madoff in prison: happily unrepentant". The Guardian. London, England. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ "Bernard Madoff enjoys eating pizza with the Mafia in prison". The Telegraph. London, England. October 21, 2009. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff asking Trump to reduce his prison sentence for massive Ponzi scheme". CNBC. July 24, 2019. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ Balsamo, Michael; Hays, Tom (April 14, 2021). "Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff dies in prison at 82". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021.

- ^ Yaffe-Bellany, David (February 5, 2020). "Bernie Madoff Says He's Dying and Seeks Early Prison Release". The New York Times.

- ^ Mangan, Dan; Forkin, Jim (June 4, 2020). "Ponzi scheme king Bernie Madoff denied compassionate prison release by federal judge". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020.

- ^ Van Voris, Bob (June 4, 2020). "Bernie Madoff Denied Compassionate Release From Prison". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (June 4, 2020). "Bernard Madoff fails to win compassionate release from prison". Reuters.

- ^ Nicas, Jack (June 4, 2020). "Judge Denies Bernie Madoff's Request for Early Release". The New York Times.

- ^ Balsamo, Michael (April 14, 2021). "Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff dies in prison at 82". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Henriques, Diana B. (April 14, 2021). "Bernie Madoff, Architect of Largest Ponzi Scheme in History, Dead at 82". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Morgan; Henney, Megan (April 30, 2021). "Bernie Madoff cause of death revealed: hypertension, atherosclerosis, kidney failure". Fox Business. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Bernie Madoff: Hypertension and kidney disease... causes of death" (PDF). TMZ. April 30, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Mozgovaya, Natasha (December 15, 2008). "Prominent Jewish foundations shut down due to Madoff Wall Street affair". Haaretz. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ a b "Madoff Wall Street fraud threatens Jewish philanthropy". Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ Friedman (December 13, 2008). "Charity Caught Up in Wall Street Ponzi Scandal". Fox News. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ Zajac, Andrew; Hook, Janet (December 22, 2008). "Madoff had steady presence in Washington". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ "NYCC Board of directors". New York City Center. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008.

- ^ Moore (December 24, 2008). "A Jewish Charity That Avoided Madoff". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ^ Sherwell (December 13, 2008). "Bernie Madoff: Profile of a Wall Street star". London: Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ Farley, Christopher John (May 30, 2013). "Woody Allen Takes on the Madoff Scandal in New Movie". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "In God We Trust – The Movie". The Halcyon Company. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Richard Dreyfuss: Like It Or Not, There's A Bit Of Bernie Madoff In All Of Us". NPR. January 28, 2016. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "'Madoff' and 'Scandal': ABC's miniseries probably means a longer wait for Olivia Pope's return | TV By The Numbers by zap2it.com". Tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com. November 13, 2015. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Radiolab Presents: Ponzi Supernova, archived from the original on February 10, 2017, retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ "Chevelle Reveal 'Face to the Floor' Was Inspired by Ponzi Scheme Victims". Loudwire.com. October 16, 2011. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Book Review: Silver Girl by Elin Hilderbrand". Seattle PI. June 28, 2011. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.