Manson Family

| Manson Family | |

|---|---|

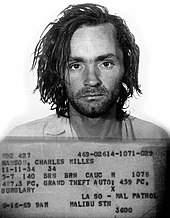

Charles Manson's 1968 mugshot | |

| Leader | Charles Manson[1] |

| Foundation | 1967 |

| Dates of operation | 1967–1969 |

| Dissolved | 1970 |

| Country | United States |

| Motives | Incitement of a race war[1] |

| Headquarters |

|

| Major actions | Murder, assault, theft |

| Notable attacks | Tate–LaBianca murders, Attempted assassination of Gerald Ford (Sacramento), Murder of Donald Shea |

| Status | Dissolved upon arrest of Manson and other members |

| Size | 100 members |

The Manson Family (known among its members as the Family) was a commune, gang, and cult led by criminal Charles Manson that was active in California in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[1][2][3] The group at its peak consisted of approximately 100 followers, who lived an unconventional lifestyle, frequently using psychoactive drugs, including amphetamine and hallucinogens such as LSD.[1][4] Most were young women from middle-class backgrounds, many of whom were attracted by hippie counterculture and communal living, and then radicalized by Manson's teachings.[1][5] The group murdered at least 9 people,[1] though they may have killed as many as 24.

Manson was born in 1934 and had been institutionalized or incarcerated for more than half of his life by the time he was released from prison in 1967. He began attracting acolytes in the San Francisco area. They gradually moved to a run-down ranch, called the Spahn Ranch, in Los Angeles County.[6] The ranch burned down during a Southern California wildfire in September 1970.

According to group member Susan Atkins, the members of the Family became convinced that Manson was a manifestation of Jesus Christ,[1] and believed in his prophecies concerning an imminent, apocalyptic race war.[1][7][8]

In 1969, Manson Family members Susan Atkins, Tex Watson, and Patricia Krenwinkel entered the home of Hollywood actress Sharon Tate and murdered her and four others. Linda Kasabian was also present, but did not take part. The following night, members of the Family murdered supermarket executive Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary at their home in Los Angeles. Members also committed a number of assaults, petty crimes, theft and street vandalism, including an assassination attempt on U.S. President Gerald Ford in 1975 by Manson Family member Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme.

Confirmed members and associates

[edit]The following is an incomplete list of individuals associated with the Manson Family cult:

- Susan Atkins (died 2009)

- Ella Jo Bailey (died 2015)

- Larry Bailey

- Susan Bartell

- Bobby Beausoleil

- Mary Brunner

- Sherry Cooper

- Madeline Cottage

- Bruce M. Davis

- Danny DeCarlo

- Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme

- Catherine Gillies (died 2018)

- Sandra Good

- Clem Grogan

- Barbara Hoyt (died 2017)

- Gregg Jakobson

- Linda Kasabian (died 2023)

- Phil Kaufman

- Patricia Krenwinkel

- Dianne Lake

- Kathryn Lutesinger

- Charles Manson (died 2017)

- Ruth Ann Moorehouse

- Dean Allen Moorehouse (died 2010)

- Nancy Pitman

- Brooks Poston

- Dennis Rice

- Stephanie Schram

- Catherine Share

- Deirdre Shaw, daughter of Angela Lansbury[9]

- George Spahn (died 1974)

- Leslie Van Houten

- Thomas Walleman

- Paul Watkins (died 1990)

- Tex Watson

Formation

[edit]

San Francisco followers

[edit]Following his release from prison on March 22, 1967, Charles Manson moved to San Francisco, where, with the help of a prison acquaintance, he moved into an apartment in Berkeley. In prison, bank robber Alvin Karpis had taught Manson to play the steel guitar.[10]: 137–146 [11][12] Living mostly by begging, Manson soon became acquainted with Mary Brunner, a 23-year-old graduate of University of Wisconsin–Madison. Brunner was working as a library assistant at the University of California, Berkeley, and Manson moved in with her. According to a second-hand account, he overcame her resistance to him bringing other women in to live with them. Before long, they were sharing Brunner's residence with eighteen other women.[10]: 163–174

Manson established himself as a guru in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, which during 1967's "Summer of Love" was emerging as the signature hippie locale. Manson may have borrowed some of his philosophy from the Process Church of the Final Judgment. Its members believed Satan would become reconciled to Jesus, and they would come together at the end of the world to judge humanity. Manson soon had the first of his groups of followers, most of them female. They were later dubbed the "Manson Family" by Los Angeles prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi and the media.[10]: 137–146 Manson allegedly taught his followers that they were the reincarnation of the original Christians, and that the establishment could be characterized as the Romans. Sometime around 1967, he began using the alias "Charles Willis Manson."[10]: 315

Before the end of summer, Manson and some of the women began traveling in an old school bus they had adapted, putting colored rugs and pillows in place of the many seats they had removed. They eventually settled in the Los Angeles areas of Topanga Canyon, and Malibu and Venice along the coast.[10]: 163–174 [13]: 13–20

In 1967, Brunner became pregnant by Manson. On April 15, 1968, she gave birth to their son, whom she named Valentine Michael, in a condemned house where they were living in Topanga Canyon. She was assisted by several of the young women from the Family. Brunner (like most members of the group) acquired a number of aliases and nicknames, including: "Marioche", "Och", "Mother Mary", "Mary Manson", "Linda Dee Manson", and "Christine Marie Euchts".[10]: xv

Manson's self-presentation

[edit]Actor Al Lewis had Manson babysit his children on a couple of occasions and described him as "a nice guy when I knew him".[14] Music producer Phil Kaufman introduced Manson to Universal Studios producer Gary Stromberg, then working on a film adaptation of the life of Jesus set in modern America. It featured a Black Jesus and southern "redneck Romans". Stromberg thought that Manson made interesting suggestions about what Jesus might do in a situation, seeming to be attuned to the role. He had one of his women kiss his feet and then kissed hers in return to demonstrate the place of women. At the beach one day, Stromberg watched while Manson preached against a materialistic outlook. One of his listeners questioned him about the well-furnished bus. Manson tossed the bus keys to the doubter, who promptly drove the bus away while Manson watched, apparently unconcerned.[15]: 124 According to Stromberg, Manson had a dynamic personality; he was able to read a person's emotional weaknesses and manipulate them.[14] For example, Manson tried to manipulate Danny DeCarlo, the treasurer of the Straight Satans motorcycle club, by granting him "access" to Family women. He convinced DeCarlo that his large penis helped keep the women in the group.[10]: 146

Involvement with Wilson, Melcher, and others

[edit]

Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys picked up Patricia Krenwinkel and Ella Jo Bailey when they were hitchhiking in late spring 1968, while under the influence of alcohol and LSD.[16] He took them to his Pacific Palisades house for a few hours. The following morning, when Wilson returned home from a night recording session, he was greeted by Manson in the driveway, who emerged from his house. Wilson asked the stranger whether he intended to hurt him. Manson assured him that he had no such intent and began kissing Wilson's feet.[10]: 250–253 [13]: 34 Inside the house, Wilson discovered 12 strangers, mostly women.[10]: 250–253 [13]: 34

The account given in Manson in His Own Words is that Manson first met Wilson at a friend's San Francisco house where Manson had gone to obtain marijuana. Manson claimed that Wilson gave him his Sunset Boulevard address and invited him to stop by when he came to Los Angeles.[11] Wilson said in a 1968 Record Mirror article that when he mentioned the Beach Boys' involvement with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi to a group of strange women, "they told me they too had a guru, a guy named Charlie."[17]

Over the next few months, the number of women doubled in Wilson's house. He covered their costs, which amounted to approximately $100,000. This total included a large medical bill for treatment of their gonorrhea, and $21,000 for the destruction of his uninsured car, which they borrowed.[18] Wilson would sing and talk with Manson, and they both treated the women as servants.[10]: 250–253 Wilson paid for studio time to record songs written and performed by Manson and introduced him to entertainment business acquaintances, including Gregg Jakobson, Terry Melcher, and Rudi Altobelli. The latter man owned a house which he rented to actress Sharon Tate and her husband, director Roman Polanski.[10]: 250–253 Jakobson was impressed by "the whole Charlie Manson package" of artist, life-stylist, and philosopher, and he paid to record his material.[10]: 155–161, 185–188, 214–219 [19] Wilson moved out of his rented home when the lease expired, and his landlord evicted the Family.[20]

Spahn Ranch

[edit]Manson established a base for the Family at the Spahn Ranch in August 1968 after Wilson's landlord evicted them.[21] It had been a television and movie set for Westerns, but the buildings had deteriorated by the late 1960s. The ranch then derived revenue primarily from selling horseback rides.[22] Female Family members did chores around the ranch and, occasionally, had sex on Manson's orders with the nearly blind 80-year-old owner George Spahn. The women also acted as guides for him. In exchange, Spahn allowed Manson and his group to live at the ranch for free.[10]: 99–113 [18]: 34, 40 Lynette Fromme acquired the nickname "Squeaky" because she often squeaked when Spahn pinched her thigh.[10]: 163–174 [18]

Charles Watson, a small-town Texan who had quit college and moved to California, soon joined the group at the ranch.[19]

Encounter with Tate

[edit]

On March 23, 1969,[10]: 228–233 Manson entered the grounds of 10050 Cielo Drive, which he had known as Melcher's residence. He was not invited.[10]: 155–161

As he approached the main house, Manson was met by Shahrokh Hatami, an Iranian photographer who had befriended Polanski and Tate during the making of the documentary Mia and Roman. He was there to photograph Tate before she departed for Rome the next day. Seeing Manson approach, Hatami had gone onto the front porch to ask him what he wanted.[10]: 228–233 Manson said that he was looking for someone whose name Hatami did not recognize. Hatami told him the place was the Polanski residence. He advised Manson to try "the back alley," by which he meant the path to the guest house beyond the main house.[10]: 228–233 Concerned about the stranger, he had gone down the front walk to confront Manson. Tate appeared behind Hatami in the house's front door and asked him who was calling. Hatami said that a man was looking for someone. He and Tate maintained their positions while Manson went back to the guest house without a word, returned to the front a minute or two later, and left.[10]: 228–233

That evening, Manson returned to the property and again went to the guest house. He entered the enclosed porch and spoke with Altobelli, the owner, who had just come out of the shower. Manson asked for Melcher, but Altobelli felt that Manson was looking for him.[10]: 226 It was later discovered that Manson had apparently been to the property on earlier occasions after Melcher left.[10]: 228–233, 369–377

Altobelli told Manson through the screen door that Melcher had moved to Malibu and said that he did not know his new address (although he did). Altobelli said that he was in the entertainment business. He had met Manson the previous year at Wilson's home and was sure that Manson already knew that. At that meeting, he had given limited compliments to Manson on some of his musical recordings, which Wilson had been playing.[10]: 228–233 Altobelli told Manson he was leaving the country the next day, and Manson said he would like to speak with him upon his return. Altobelli said that he would be gone for more than a year. Manson said that he had been directed to the guest house by the persons in the main house; Altobelli asked Manson not to disturb his tenants.[10]: 228–233

Altobelli and Tate flew together to Rome the next day. Tate asked him whether "that creepy-looking guy" had gone to see him at the guest house the day before.[10]: 228–233

Crimes

[edit]Crowe shooting

[edit]| Bernard Crowe shooting | |

|---|---|

| Location | Franklin Garden Apartments, 6917–6933 Franklin Avenue, Los Angeles, California |

| Date | July 1, 1969 (PDT) |

Attack type | Shooting |

| Weapons | .22 caliber High Standard Buntline revolver[23] |

| Deaths | 0 |

| Injured | 1 |

| Victims | Bernard "Lotsapoppa" Crowe[24] |

| Perpetrator | Charles Manson; accomplices – Tex Watson, Thomas "T.J." Walleman |

Tex Watson became involved in drug dealing[25] and robbed a drug dealer named Bernard "Lotsapoppa" Crowe. Crowe allegedly responded with a threat to kill everyone at Spahn Ranch. In response, Charles Manson shot Crowe on July 1, 1969, at Manson's Hollywood apartment.[10]: 91–96, 99–113 [13]: 147–149 [19]

Manson's belief that he had killed Crowe was seemingly confirmed by a news report of the discovery of the dumped body of a Black Panther in Los Angeles. Although Crowe was not a member of the Black Panthers, Manson concluded he had been and expected retaliation from the Panthers. He turned Spahn Ranch into a defensive camp, establishing night patrols by armed guards.[19][13]: 151 Tex Watson would later write, "Blackie was trying to get at the chosen ones."[19]

Manson brought in members of the Straight Satans Motorcycle Club to act as security. At this time, Bobby Beausoleil became more involved with the Family.[25]

Hinman murder

[edit]| Gary Hinman murder | |

|---|---|

| Location | 964 Old Topanga Canyon Road, Topanga, California |

| Date | July 25, 1969– July 27, 1969 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| Target | Gary Allen Hinman[26] |

Attack type | Stabbing |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Perpetrator | Bobby Beausoleil; accomplices – Susan Atkins, Mary Brunner, Charles Manson, Bruce M. Davis |

Gary Allen Hinman (b. December 24, 1934 in Colorado) was a music teacher and PhD student at UCLA. At some point in the late 1960s, he befriended members of the Manson Family, allowing some to occasionally stay at his home.[26] According to some people, including Family member Susan Atkins, Manson believed Hinman was wealthy. He sent Family members Bobby Beausoleil, Mary Brunner and Atkins to Hinman's home on July 25, 1969, to convince him to join the Family and turn over the assets Manson thought Hinman had inherited.[10]: 75–77 [19][27][28] The three held Hinman hostage for two days, as he denied having any money. During this time, Manson arrived with a sword and slashed Hinman's face and ear. After that, Beausoleil stabbed Hinman to death, allegedly on Manson's instruction. Before leaving the Topanga Canyon residence, Beausoleil or one of the women used Hinman's blood to write "Political piggy" on the wall and to draw a panther paw, a Black Panther symbol.[10]: 33, 91–96, 99–113 [13]: 184

According to Manson and Beausoleil in magazine interviews of 1981 and 1998–1999,[29] Beausoleil said he went to Hinman's to recover money paid to Hinman for mescaline provided to the Straight Satans that had supposedly been bad.[25] Beausoleil added that Brunner and Atkins, unaware of his intent, went along to visit Hinman. Atkins, in her 1977 autobiography, wrote that Manson directed Beausoleil, Brunner, and her to go to Hinman's and get the supposed inheritance of $21,000. She said that two days earlier Manson had told her privately that, if she wanted to "do something important", she could kill Hinman and get his money.[27]

Beausoleil was arrested on August 6, 1969, after he was caught driving Hinman's car. Police found the murder weapon in the tire well.[10]: 28–38

Murders of Tate, Sebring, Folger, Frykowski, and Parent

[edit]On the night of August 8, 1969, Manson directed Tex Watson to take Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian, and Patricia Krenwinkel to Melcher's former home at 10050 Cielo Drive in Los Angeles. According to Watson, Manson told them to kill everyone there. The home had recently been rented to actress Sharon Tate and her husband, director Roman Polanski. (Polanski was away in Europe working on The Day of the Dolphin). Manson told the three women to do as Watson told them.

The Family members killed the five people they found: Sharon Tate (eight and a half months pregnant), who was living there at the time, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, and Wojciech Frykowski, who were visiting her, and Steven Parent, who had been visiting the caretaker of the home. Atkins wrote "pig" with Tate's blood on the front door as they left. The murders created a nationwide sensation.[30]

Murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca

[edit]The night of August 9, 1969, seven Family members (Leslie Van Houten, Steve "Clem" Grogan, Charles Manson, and the four from the previous night) drove to[10]: 176–184, 258–269 [19] the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca.[10]: 22–25, 42–48 Watson said that, having gone there alone, Manson returned to take him to the house with him. After Manson pointed through a window to a man sleeping in the living room, the two men entered the house through an unlocked back door.[19] Watson bound the couple and covered their heads with pillowcases. Manson left, sending Krenwinkel and Van Houten into the house.[10]: 176–184, 258–269 [19]

Watson sent the women to the bedroom where Rosemary had been bound. He began stabbing Leno with a bayonet in the living room.[19] Going to the bedroom, Watson discovered Rosemary swinging a lamp at the Family women. He stabbed her with the bayonet, and returned to the living room to resume attacking Leno, whom he stabbed 12 times.[19] Krenwinkel stabbed Rosemary. Watson told Van Houten to stab the woman, too,[19] which she did.[10]: 204–210, 297–300, 341–344 Krenwinkel used the LaBiancas' blood to write "Rise" and "Death to pigs" on the walls, and "Healter [sic] Skelter" on the refrigerator door.[10]: 176–184, 258–269 [19]

Meanwhile, Manson directed Kasabian to drive to the home of an acquaintance of hers. Manson dropped off Kasabian, Grogan, and Atkins, and drove back to Spahn Ranch.[10]: 176–184, 258–269 Kasabian allegedly thwarted a murder by deliberately knocking on the wrong door.[10]: 270–273

Shea murder

[edit]In a 1971 trial that took place after his Tate–LaBianca convictions, Manson was found guilty of the murders of Gary Hinman and Donald "Shorty" Shea. He was given a life sentence. Shea was a Spahn Ranch stuntman and horse wrangler who had been killed approximately ten days after a sheriff's raid on the ranch which had been carried out on 16 August 1969. Manson, who suspected that Shea had helped set up the raid, apparently believed Shea was trying to get Spahn to run the Family off the ranch. Manson may have considered it a "sin" that Shea, a white man, had married a black woman. Furthermore, there was the possibility that Shea knew about the Tate–LaBianca killings.[10]: 99–113 [13]: 271–272 In separate trials, Family members Bruce Davis and Steve "Clem" Grogan were also found guilty of Shea's murder.[10]: 99–113, 463–468 [31]

In 1977, authorities learned the exact location of the remains of Shorty Shea and, contrary to Family claims, also learned that Shea had not been dismembered and buried in several places. Contacting the prosecutor in his case, Steve Grogan told him Shea's corpse had been buried intact. Grogan drew a map that pinpointed the location, and the body was recovered. Of those convicted of Manson-ordered murders, Grogan would become, in 1985, the first one to be paroled.[10]: 509

Suspected further murders

[edit]In total, Manson and his followers were convicted of nine counts of first-degree murder. However, the LAPD believes that the Family could have claimed up to at least twelve more victims.[32][33][34] Cliff Shepard, a former LAPD Robbery-Homicide Division detective, said that Manson "repeatedly" claimed to have killed many others. Prosecutor Stephen Kay supported this assertion: "I know that Manson one time told one of his cellmates that he was responsible for 35 murders." Tate's younger sister, Debra Tate, has also claimed that investigators are "just scraping the surface" when it comes to the number of Manson's victims and has further elaborated on how Manson sent her a taunting map of the Panamint Range, with crosses on it that she believed were meant to represent buried bodies. This has resulted in several excavations that have been undertaken at Manson's Barker Ranch, but they have not resulted in any bodies being found.[35]

- Nancy Warren, 64, and Clyda Dulaney, 24, were both found near Ukiah, California at the antique store owned by Warren on October 13, 1968. They had both been beaten and strangled to death with thirty-six leather thongs.[36] After the Family members were arrested, they became suspects when it was discovered that members of the Family had been in the Ukiah area at the time of the murders. However, no one in the Family was ever charged with the murders and no arrests were ever made in the case.

- Marina Elizabeth Habe, 17, was murdered on December 30, 1968. She was a student at the University of Hawaii home on vacation when she was murdered in Los Angeles.[37][38] According to the autopsy report, Habe's throat had been slashed and she had received numerous knife wounds to the chest. She suffered multiple contusions to the face and throat, and had been garrotted. There was no evidence of rape.[39] Habe was abducted outside the home of her mother in West Hollywood, 8962 Cynthia Avenue.[40] A former Manson Family associate claimed members of the Family had known Habe and it was conjectured she had been one of their victims.[38][41]

- Darwin Morell Scott, 64, was the uncle of Manson and the brother of Manson's father, Colonel Scott. On May 27, 1969, Scott was found brutally stabbed to death in his Ashland, Kentucky apartment. His body was pinned to the kitchen floor with a butcher knife, and he had been stabbed nineteen times. After Manson's arrest, it was reported that local residents claimed to have seen a man resembling Manson using the alias, "Preacher", in the area at the time Darwin was murdered. Manson was on parole in California at the time of the murder, but the murder occurred when Manson was out of touch with his parole officers.[42]

- Mark Walts, 16, was an acquaintance of the Family members and was even known to associate with them at the Spahn Ranch. On July 17, 1969, Walts hitchhiked to the Santa Monica Pier so he could go fishing. His fishing pole was found abandoned at the pier, and his body was found the next day near Mulholland Drive. He had been shot three times in the chest. Though the Family was reportedly "shocked" by Walts' murder, his brother was convinced that Manson was responsible for his death and even called him in order to directly accuse him of his murder. The Los Angeles Sheriff's Department investigated Spahn Ranch in regard to Walts' murder, but no links were found, and the murder was never solved.[43]

- John Philip Haught, 22, was an Ohio native who had moved to California and met Manson in the summer of 1969. He joined the Manson Family and was amongst the group who was arrested in the October raid of the clan for the Tate-LaBianca murders; Manson suspected him of being an informant. On November 5, 1969, Haught was associating with some members of the Family. According to all present, Haught suddenly found a gun in the room, picked it up, and promptly shot himself while attempting a game of Russian roulette. However, when police investigated the death, they found that the gun, rather than having zero bullets and one spent shell casing, instead contained seven bullets and one spent shell. Moreover, the gun had been wiped free of prints. Additionally, a male witness who had held Haught's head after the shooting told Cohen he had entered the room to find a female Manson follower with the gun in her hand.[44] Despite this, police concluded Haught had actually killed himself.

- James Sharp, 15, and Doreen Gaul, 19, were both found stabbed to death in an alley in Los Angeles on November 7, 1969. The murder of the two young Scientologists involved both being stabbed between fifty and sixty times. Police immediately noted the similarities to these murders and those of the Tate-LaBianca murders;[45] the killings of Sharp and Gaul happened close to where the Labianca's lived. In Helter Skelter, author Vincent Bugliosi wrote that Gaul was rumoured to be a former girlfriend of Manson Family member Bruce Davis — Davis had lived at the same housing complex as Gaul, but in a police interview he denied knowing her.

- Reet Jurvetson, 19, was a young woman found stabbed to death on November 16, 1969.[46] Her body was found with over one hundred and fifty stab wounds from a penknife to her neck and upper body, along with defensive wounds on her hands and arms. She had been disposed of along Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles, California.[47] Some witnesses claimed to have seen a woman named "Sherry" who matched Jurvetson's description among members of the Manson Family, but it turned out that this individual was alive. Manson himself denied any involvement in killing Jurvetson. Detectives within the Los Angeles Police Department have noted "striking similarities" between the method of murder of both Jurvetson and Habe, but no firm connection between both murders has ever been established.[48]

- Joel Pugh, 29, was found dead in the Talgarth Hotel in London, England, on December 1, 1969. His wrists had been cut and his throat was slit twice. British authorities listed the death a drug-induced suicide, saying Pugh had been depressed. Pugh was a Family member who was married to another member of the Family, Sandra Good. Stephen Kay and others claim Manson hated Pugh. "He had no reason to commit suicide, and Manson was very unhappy that Sandy was with Pugh", Kay has said. Pugh's death occurred when a number of Manson Family members were being arrested for the Tate-LaBianca murders. Manson follower Bruce Davis was in London at the time Pugh died.[33]

- Ronald Hughes, 35, was an American attorney who represented Leslie Van Houten, a member of the Manson Family. Hughes disappeared while on a camping trip during a ten-day recess from the Tate-LaBianca murder trial in November 1970. The badly decomposed body of Hughes was found in March 1971 wedged between two boulders in Ventura County.[10]: 457 It was rumoured, although never proven, that Hughes was murdered by the Family, possibly because he had stood up to Manson and refused to allow Van Houten to take the stand and absolve Manson of the crimes,[10]: 387, 394, 481 though he might have perished in flooding.[10]: 393–394, 481 [13]: 436–438 Attorney Stephen Kay has stated that while he is "on the fence" about the Family's involvement in Hughes' death, Manson had open contempt for Hughes during the trial. Kay added, "The last thing Manson said to him [Hughes] was, 'I don't want to see you in the courtroom again,' and he was never seen again alive."[49] Family member Sandra Good stated that Hughes was "the first of the retaliation murders".[10]: 481–482, 625

- On November 8, 1972, the body of 26-year-old Vietnam Marine combat veteran James Lambert Willett was found by a hiker near Guerneville, California.[50] Months earlier, he had been forced to dig his own grave, and then was shot and poorly buried. His station wagon was found outside a house in Stockton where several Manson followers were living, including Priscilla Cooper, Lynette Fromme, and Nancy Pitman. Police forced their way into the house and arrested several of the people there. The body of Willett's 19-year-old wife Lauren Chavelle Willett[51] was found buried in the basement.[50] She had been killed very recently by a gunshot to the head, in what the Family members initially claimed was an accident. It was later suggested that she was killed out of fear that she would reveal who killed her husband. Michael Monfort pleaded guilty to murdering Lauren and Priscilla Cooper, James Craig, and Nancy Pitman pleaded guilty as accessories after the fact. Monfort and William Goucher later pleaded guilty to the murder of James, and James Craig pleaded guilty as an accessory after the fact. The group had been living in the house with the Willetts while committing various robberies. Shortly after killing Willett, Monfort had used Willett's identification papers to pose as Willett after being arrested for an armed robbery of a liquor store. Willett was not involved in the robberies[52] and wanted to move away but was presumably killed out of fear that he would talk to police.

- Laurence Merrick, 50, was an American film director and author. He is best known for co-directing the Oscar nominated documentary Manson in 1973. Sharon Tate was a former student at Merrick's Academy of Dramatic Arts.[53] Merrick was killed by a gunman on January 26, 1977. He was shot in the back in the carpark of his acting school. Merrick's murder went unsolved until October 1981 when 35-year-old Dennis Mignano confessed to police. At his subsequent trial, Mignano was found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a mental hospital. Mignano was an unemployed would-be actor and singer with a long history of psychiatric problems and a possible prior relationship with the Manson clan.[54]

- Six months after the murder of Merrick, Mignano's sister Michele Mignano, 21, a topless dancer, was also murdered. Her body was found on June 13, 1977, 350 ft into a Western Pacific railroad tunnel in Niles Canyon. Authorities referred to her death as an "execution-style slaying" with her dying from exsanguination due to multiple gunshot wounds. A number of bullet cartridges were found near her body. She was shoeless yet fully clothed with jewellery so sexual assault and robbery were both ruled out as motives. Her murder has never been solved.[55][56]

Possible murder motives

[edit]Helter Skelter

[edit]In November 1968, the Family had established headquarters in Death Valley's environs, at the Myers and Barker ranches.[19][18] The former was owned by the grandmother of Family member Catherine Gillies.[18]

According to Charles Watson and Paul Watkins, Manson and Watson visited an acquaintance who played the Beatles' double album, The Beatles,[19][18] and became obsessed with the group.[57]

Watkins claimed Manson had been saying that racial tensions between Blacks and Whites were about to erupt, predicted that Black Americans would rise up in rebellion,[19][58] and that The Beatles' songs foretold it all in code.[19][58]

According to Watkins, by February, the Family would create an album whose songs would trigger the predicted chaos. Murders of Whites by Blacks would be met with retaliation. A split between racist and non-racist Whites would result in the Whites' self-annihilation.[59]

Copycat

[edit]According to Family members Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie Van Houten,[10]: 426–435 Bobby Beausoleil, and others, the arrest of Beausoleil for the torture and murder of Gary Hinman was the catalyst for the Family's ensuing murder spree. They wanted to convince police that the killer(s) of Hinman were still at large. Truman Capote's interviews of Beausoleil, and that by Ann Louise Bardach in November 1981, affirmed this account.[60][61]

Charlie Guenther, a police detective who investigated the murders, said of Beausoleil, "He called the [Spahn] Ranch after he was arrested. The sole motive for those murders was to get Bobby out of jail."[62]: 149 Bugliosi's co-prosecutor Aaron Stovitz said he believed the motive for the Tate–LaBianca murders was as copycat murders after Hinman.[62]: 151–152

Drugs

[edit]Other people suggested the motive was related to the drug dealing by Jay Sebring and Voytek Frykowski, and their connection with Charles Watson and Manson, and a bad drug deal.[63][64][62] For instance, Sebring's protégé Jim Markham believes the murders were in response to a bad drug deal the day before, in which Manson went to Tate's house to sell marijuana and cocaine to Sebring and Frykowski. Instead, the two men attacked and beat Manson.[64] In an interview with police, Frykowski's friend Witold Kaczanowski said that Frykowski had been involved with many criminals and the drug trade.[62]: 56–57 In his later interview with Truman Capote, Bobby Beausoleil said, "They burned people on dope deals. Sharon Tate and that gang."[60]: 460

Ed Sanders and Paul Krassner uncovered information that Joel Rostau, the boyfriend of Sebring's receptionist, had delivered mescaline and cocaine to Sebring and Frykowski at Tate's house a few hours before the murders. During the Manson trial, Rostau and other associates of Sebring were murdered.[65]

Terry Melcher

[edit]In 1968, musician Dennis Wilson introduced record producer Terry Melcher to Manson.[66] For a time, Melcher was interested in recording Manson's music, as well as making a film about the family and their hippie commune existence. Manson met Melcher at 10050 Cielo Drive, a house that Melcher shared with his girlfriend, actress Candice Bergen, and musician Mark Lindsay.[67]

Manson eventually auditioned for Melcher, but Melcher declined to sign him. There was still talk of a documentary being made about Manson's music, but Melcher abandoned the project after witnessing Manson fighting with a drunken stuntman at Spahn Ranch.[68] Wilson and Melcher severed their ties with Manson, a move that angered Manson.[69] Soon after, Melcher and Bergen moved out of the Cielo Drive home. The house's owner, Rudi Altobelli, then leased it to film director Roman Polanski and his wife, actress Sharon Tate. Manson was reported to have visited the house on more than one occasion asking for Melcher, but was told that Melcher had moved.[68]

Some authors and law enforcement personnel[who?] have theorized that the Cielo Drive house was targeted by Manson as revenge for Melcher's rejection and that Manson was unaware that he and Bergen had moved out. However, family member Charles "Tex" Watson stated that Manson and company did, in fact, know that Melcher was no longer living there,[70] and Melcher's former roommate Mark Lindsay stated, "Terry and I talked about it later and Terry said Manson knew (Melcher had moved) because Manson or someone from his organization left a note on Terry's porch in Malibu."[67]

The Manson murders reportedly prompted Melcher to go into seclusion. When Manson was arrested, it was widely reported that he had sent his followers to the house to kill Melcher and Bergen. Manson family member Susan Atkins, who admitted her part in the murders, stated to police and before a grand jury that the house was chosen as the scene for the murders "to instill fear into Terry Melcher because Terry had given us his word on a few things and never came through with them".[68] Melcher took to employing a bodyguard and told Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi that his fear was so great he had been undergoing psychiatric treatment. Melcher was described as the most frightened of the witnesses at the trial, even though Bugliosi assured him that "Manson knew you were no longer living [on Cielo Drive]".[68]

In his 2019 book CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, Tom O'Neil reexamined the Manson case and found evidence Melcher may have been more closely involved with the Manson family than he admitted at trial.[71] In reviewing police files and other data, O'Neill found evidence Melcher was associating with Manson in the four month period after the Tate-Labianca murders but before Manson's arrest. These documents, seemingly hidden by Bugliosi, undermined claims the Tate murders were intended to frighten Melcher in revenge for his refusal to record Manson's music. O'Neill also found documents indicating Melcher was having sex with 15-year-old Manson family member Ruth Ann Moorehouse.[72] Dean Moorehouse, Ruth Ann's father and a Manson Family member, also had resided at 10050 Cielo Drive with Melcher. Tex Watson would also frequently visit the residence.[72]: 117–119

Investigation and trial

[edit]Investigation

[edit]The Tate murders became national news on August 9, 1969. The Polanskis' housekeeper, Winifred Chapman, had discovered the murder scene when she arrived for work that morning.[10]: 5–6, 11–15 On August 10, detectives of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, which had jurisdiction in the Hinman case, informed Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) detectives assigned to the Tate case of the bloody writing at the Hinman house. According to Vincent Bugliosi, because detectives believed the Tate murders were a consequence of a drug transaction, the Tate team initially ignored this and other evidence of similarities between the crimes.[10]: 28–38 [13]: 243–244 The Tate autopsies were underway before the LaBianca bodies were discovered.[citation needed]

During the Tate autopsies, detectives working on the Gary Hinman case noticed similarities in the weapons used, the stab wounds, and the writing in blood on the walls. They also thought the case had something to do with narcotics. They brought the information to detectives working on the Tate murders. According to Detective Charlie Guenther, "Vince [Bugliosi] didn't want anything to do with the Hinman case. Hinman was a nothing case. Vince didn't want to prosecute it."[62]: 148–151

Steven Parent, who was fatally shot in the Tate/Polanski driveway, was found to have been an acquaintance of William Garretson, the caretaker who lived in the guest house. Garretson had been hired by Rudi Altobelli to take care of the property while Altobelli was away.[10]: 28–38 The killers encountered Parent when he was leaving after he had visited Garretson.[10]: 28–38

Held briefly as a Tate suspect, Garretson told police he had neither seen nor heard anything on the murder night. He was released on August 11, 1969, after undergoing a polygraph examination that indicated he had not been involved in the crimes.[10]: 28–38, 42–48

The LaBianca crime scene was discovered at about 10:30 p.m. on August 10, approximately 19 hours after the murders were committed. Fifteen-year-old Frank Struthers, Rosemary's son from a prior marriage and Leno's stepson, returned from a camping trip and was concerned to see all of the window shades of his home drawn and his stepfather's speedboat still attached to the family car, parked in the driveway. He called his older sister and her boyfriend. The boyfriend, Joe Dorgan, accompanied the younger Struthers into the house, where they discovered Leno's body. They called the police, who found Rosemary's body after officers arrived at the house.[10]: 38

On August 12, 1969, the LAPD told the press it had ruled out any connection between the Tate and LaBianca homicides.[10]: 42–48 On August 16, the sheriff's office raided Spahn Ranch and arrested Manson and 25 others, as "suspects in a major auto theft ring" that had been stealing Volkswagen Beetles and converting them into dune buggies. Weapons were seized, but, because the search warrant had been misdated, the group was released a few days later.[10]: 56

In a report at the end of August, the LaBianca detectives noted a possible connection between the bloody writings at the LaBianca house and "the singing group the Beatles' most recent album."[10]: 65

Breakthrough

[edit]Still working separately from the Tate team, the LaBianca team checked with the sheriff's office in mid-October about possible similar crimes. They learned of the Hinman case. They also learned that the Hinman detectives had spoken with Beausoleil's girlfriend, Kitty Lutesinger. She had been arrested a few days earlier with members of "the Manson Family".[10]: 75–77

The arrests, for car thefts, had taken place at the desert ranches to which the Family had moved. Unknown to authorities, its members had been searching Death Valley for a hole in the ground, what they believed was access to the Bottomless Pit.[10]: 228–233 [18][19] A joint force of National Park Service Rangers and officers from the California Highway Patrol and the Inyo County Sheriff's Office: federal, state, and county personnel, had raided both the Myers and Barker ranches after following evidence left when Family members had burned an earthmover owned by Death Valley National Monument.[10]: 125–127 [13]: 282–283 [18] The raiders had found stolen dune buggies and other vehicles, and had arrested two dozen people, including Manson. A Highway Patrol officer found Manson hiding in a cabinet beneath Barker's bathroom sink. The officers had no idea that the people they were arresting were involved with the murders in Los Angeles.[10]: 75–77, 125–127

Following up leads a month after they had spoken with Lutesinger, LaBianca detectives contacted members of a motorcycle gang Manson tried to recruit as bodyguards while the Family was at Spahn Ranch.[10]: 75–77 While the gang members were providing information that suggested a link between Manson and the Tate/LaBianca murders,[10]: 84–90, 99–113 a dormitory mate of Susan Atkins informed LAPD of the Family's involvement in the crimes.[10]: 99–113 Atkins was booked for the Hinman murder after she told sheriff's detectives that she had been involved in it.[10]: 75–77 [73] Transferred to Sybil Brand Institute, a detention center in Monterey Park, California, she had begun talking to bunkmates Ronnie Howard and Virginia Graham, to whom she gave accounts of the events in which she had been involved.[10]: 91–96

Apprehension

[edit]

On December 1, 1969, acting on the information from these sources, LAPD announced warrants for the arrest of Watson, Krenwinkel, and Kasabian in the Tate case; the suspects' involvement in the LaBianca murders was noted. Manson and Atkins, already in custody, were not mentioned; the connection between the LaBianca case and Van Houten, who was also among those arrested near Death Valley, had not yet been recognized.[10]: 125–127, 155–161, 176–184

Watson and Krenwinkel were already under arrest, with authorities in McKinney, Texas and Mobile, Alabama having picked them up on notice from LAPD.[10]: 155–161 Informed that a warrant was out for her arrest, Kasabian voluntarily surrendered to authorities in Concord, New Hampshire on December 2.[10]: 155–161

Before long, physical evidence such as Krenwinkel's and Watson's fingerprints, which had been collected by LAPD at Cielo Drive,[10]: 15, 156, 273, and photographs between 340–41 was augmented by evidence recovered by the public. On September 1, 1969, the distinctive .22-caliber Hi Standard "Buntline Special" revolver Watson used on Parent, Sebring, and Frykowski had been found and given to the police by Steven Weiss, a 10-year-old who lived near the Tate residence.[10]: 66 In mid-December, when the Los Angeles Times published a crime account based on information Susan Atkins had given her attorney,[10]: 160, 193 Weiss's father made several phone calls which finally prompted LAPD to locate the gun in its evidence file and connect it with the murders via ballistics tests.[10]: 198–199

Acting on that same newspaper account, a local ABC television crew quickly located and recovered the bloody clothing discarded by the Tate killers.[10]: 197–198 The knives discarded en route from the Tate residence were never recovered, despite a search by some of the same crewmen and months later by LAPD.[10]: 198, 273 A knife found behind the cushion of a chair in the Tate living room was apparently that of Susan Atkins, who lost her knife in the course of the attack.[10]: 17, 180, 262 [27]: 141

Trial

[edit]| The People v. Charles Manson et al. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Los Angeles County Superior Court |

| Full case name | The People of the State of California vs. Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Susan Atkins |

| Decided | January 25, 1971 |

| Case history | |

| Appealed to | Supreme Court of California |

| Court membership | |

| Judge sitting | Charles H. Older[74] |

| Case opinions | |

| Vogel, J., with Thompson, J., concurring. Separate concurring and dissenting opinion by Wood, P. J[75] | |

| Decision by | Jury |

The trial began June 15, 1970.[10]: 297–300 The prosecution's main witness was Kasabian, who along with Manson, Atkins, and Krenwinkel had been charged with seven counts of murder and one of conspiracy.[10]: 185–188 Since Kasabian, by all accounts, had not participated in the killings, she was granted immunity in exchange for testimony that detailed the nights of the crimes.[10]: 214–219, 250–253, 330–332 Originally, a deal had been made with Atkins in which the prosecution agreed not to seek the death penalty against her in exchange for her grand jury testimony on which the indictments were secured; once Atkins repudiated that testimony, the deal was withdrawn.[10]: 169, 173–184, 188, 292 Because Van Houten had participated only in the LaBianca killings, she was charged with two counts of murder and one of conspiracy.

Originally, Judge William Keene had reluctantly granted Manson permission to act as his own attorney. Because of Manson's conduct, including violations of a gag order and submission of "outlandish" and "nonsensical" pretrial motions, the permission was withdrawn before the trial's start.[10]: 200–202, 265 Manson filed an affidavit of prejudice against Keene, who was replaced by Judge Charles Older.[10]: 290 On Friday, July 24, the first day of testimony, Manson appeared in court with an X carved into his forehead. He issued a statement that he was "considered inadequate and incompetent to speak or defend [him]self"—and had "X'd [him]self from [the establishment's] world."[10]: 310 [13]: 388 Over the following weekend, the female defendants duplicated the mark on their own foreheads, as did most Family members within another day or so.[10]: 316

The prosecution argued that triggering the "Helter Skelter" scenario was Manson's main motive.[10] Present at the crime scene were the words "PIGS" and "HEALTER SKELTER" [sic][10]: 176–184 written in blood by Susan Atkins, a reference to the Beatles' song "Helter Skelter" from their 1968 album. These messages correlated with testimony about Manson's predictions that Black people would murder white people and write similar warnings in blood at the outset of Helter Skelter.[10]: 244–247, 450–457 The defendants testified that the writing on the walls was to imitate the Hinman murder scene, not an apocalyptic race war.[10]: 426–435

According to Bugliosi, Manson directed Kasabian to hide a wallet taken from the scene in the women's restroom of a service station near a Black neighborhood.[10]: 176–184, 190–191, 258–269, 369–377 However, as co-prosecutor Stephen Kay later pointed out the wallet was actually left about 20 miles away in a predominantly White neighborhood, Sylmar.[76]

Ongoing disruptions

[edit]During the trial, Family members loitered near the entrances and corridors of the courthouse. To keep them out of the courtroom proper, the prosecution subpoenaed them as prospective witnesses, who would not be able to enter while others were testifying.[10]: 309 When the group established itself in vigil on the sidewalk, some members wore sheathed hunting knives[citation needed] that, although in plain view, were carried legally. Each of them was also identifiable by the X on their forehead.[10]: 339

Some Family members attempted to dissuade witnesses from testifying. Prosecution witnesses Paul Watkins and Juan Flynn were both threatened;[10]: 280, 332–335 Watkins was badly burned in a suspicious fire in his van.[10]: 280 Former Family member Barbara Hoyt, who had overheard Susan Atkins describing the Tate murders to Family member Ruth Ann Moorehouse, agreed to accompany the latter to Hawaii. There, Moorehouse allegedly gave her a hamburger spiked with several doses of LSD. Found sprawled on a Honolulu curb in a drugged semi-stupor, Hoyt was taken to the hospital, where she did her best to identify herself as a witness in the Tate–LaBianca murder trial. Before the incident, Hoyt had been a reluctant witness; after the attempt to silence her, her reticence disappeared.[10]: 348–350, 361

On August 4, despite precautions taken by the court, Manson flashed the jury a Los Angeles Times front page whose headline was "Manson Guilty, Nixon Declares". This was a reference to a statement made the previous day when U.S. President Richard Nixon had decried what he saw as the media's glamorization of Manson. Voir dired by Judge Charles Older, the jurors contended that the headline had not influenced them. The next day, the female defendants stood up and said in unison that, in light of Nixon's remark, there was no point in going on with the trial.[10]: 323–238

On October 5, Manson was denied the court's permission to question a prosecution witness whom defense attorneys had declined to cross-examine. Leaping over the defense table, Manson attempted to attack the judge. Wrestled to the ground by bailiffs, he was removed from the courtroom with the female defendants, who had subsequently risen and begun chanting in Latin.[10]: 369–377 Thereafter, Older allegedly began wearing a revolver under his robes.[10]: 369–377

Defense rests

[edit]On November 16, the prosecution rested its case. Three days later, after arguing standard dismissal motions, the defense stunned the court by resting as well, without calling a single witness. Shouting their disapproval, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten demanded their right to testify.[10]: 382–388

In chambers, the women's lawyers told the judge their clients wanted to testify that they had planned and committed the crimes and that Manson had not been involved.[10]: 382–388 By resting their case, the defense lawyers had tried to stop this; Van Houten's attorney, Ronald Hughes, vehemently stated that he would not "push a client out the window". In the prosecutor's view, it was Manson who was advising the women to testify in this way as a means of saving himself.[10]: 382–388 Speaking about the trial in a 1987 documentary, Krenwinkel said, "The entire proceedings were scripted—by Charlie."[77]

The next day, Manson testified. The jury was removed from the courtroom. According to Vincent Bugliosi it was to make sure Manson's address did not violate the California Supreme Court's decision in People v. Aranda by making statements implicating his co-defendants.[10]: 134 However, Bugliosi argued Manson would use his hypnotic powers to unfairly influence the jury.[78] Speaking for more than an hour, Manson said, among other things, that "the music is telling the youth to rise up against the establishment." He said, "Why blame it on me? I didn't write the music." "To be honest with you," Manson also stated, "I don't recall ever saying 'Get a knife and a change of clothes and go do what Tex says.'"[10]: 388–392

As the body of the trial concluded and with the closing arguments impending, defense attorney Hughes disappeared during a weekend trip.[10]: 393–398 When Maxwell Keith was appointed to represent Van Houten in Hughes' absence, a delay of more than two weeks was required to permit Keith to familiarize himself with the voluminous trial transcripts.[10]: 393–398 No sooner had the trial resumed, just before Christmas, than disruptions of the prosecution's closing argument by the defendants led Older to ban the four defendants from the courtroom for the remainder of the guilt phase. This may have occurred because the defendants were acting in collusion with each other and were simply putting on a performance, which Older said was becoming obvious.[10]: 399–407

Conviction and penalty phase

[edit]On January 25, 1971, the jury returned guilty verdicts against the four defendants on each of the 27 separate counts against them.[10]: 411–419 Not far into the trial's penalty phase, the jurors saw, at last, the defense that Manson—in the prosecution's view—had planned to present.[10]: 455 Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten testified the murders had been conceived as "copycat" versions of the Hinman murder, for which Atkins now took credit. The killings, they said, were intended to draw suspicion away from Bobby Beausoleil by resembling the crime for which he had been jailed. This plan had supposedly been the work of, and carried out under the guidance of, not Manson, but someone allegedly in love with Beausoleil—Linda Kasabian.[10]: 424–433 Among the narrative's weak points was the inability of Atkins to explain why, as she was maintaining, she had written "political piggy" at the Hinman house in the first place.[10]: 424–433, 450–457

Midway through the penalty phase, Manson shaved his head and trimmed his beard to a fork; he told the press, "I am the Devil, and the Devil always has a bald head."[10]: 439 In what the prosecution regarded as belated recognition on their part that imitation of Manson only proved his domination, the female defendants refrained from shaving their heads until the jurors retired to weigh the state's request for the death penalty.[10]: 439, 455

The effort to exonerate Manson via the "copycat" scenario failed. On March 29, 1971, the jury returned verdicts of death against all four defendants on all counts.[10]: 450–457 On April 19, 1971, Judge Older sentenced the four to death.[10]: 458–459

Aftermath

[edit]1970s–1980s

[edit]Watson returned to McKinney, Texas after the Tate–LaBianca murders. He was arrested in Texas on November 30, 1969, after local police were notified by California investigators that his fingerprints were found to match a print found on the front door of the Tate home. Watson fought extradition to California long enough that he was not included among the three defendants tried with Manson.[79][citation needed] The trial commenced in August 1971; by October, he, too, had been found guilty on seven counts of murder and one of conspiracy. Unlike the others, Watson presented a psychiatric defense; prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi made short work of Watson's insanity claims. Like his co-conspirators, Watson was sentenced to death.[10]: 463–468

In February 1972, the death sentences of all five parties were automatically reduced to life in prison by People v. Anderson, 493 P.2d 880, 6 Cal. 3d 628 (Cal. 1972), in which the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in that state.[10]: 488–491 After his return to prison, Manson's rhetoric and hippie speeches held little sway. Though he found temporary acceptance from the Aryan Brotherhood, his role was submissive to a sexually aggressive member of the group at San Quentin.[80]

Before the conclusion of Manson's Tate–LaBianca trial, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times tracked down Manson's mother, remarried and living in the Pacific Northwest. The former Kathleen Maddox claimed that, in childhood, her son had suffered no neglect; he had even been "pampered by all the women who surrounded him".[81]

Remaining in view

[edit]

On September 5, 1975, the Family returned to national attention when Squeaky Fromme attempted to assassinate U.S. President Gerald Ford.[10]: 502–511 The attempt took place in Sacramento, to which she and fellow Manson follower Sandra Good had moved so that they could be near Manson while he was incarcerated at Folsom State Prison. A subsequent search of the apartment shared by Fromme, Good, and another Family recruit turned up evidence that, coupled with later actions on the part of Good, resulted in Good's conviction for conspiring to send threatening communications through the United States mail service and for transmitting death threats by way of interstate commerce. The threats involved corporate executives and U.S. government officials vis-à-vis supposed environmental dereliction on their part.[10]: 502–511 Fromme was sentenced to 15 years to life, becoming the first person sentenced under United States Code Title 18, chapter 84 (1965),[82] which made it a Federal crime to attempt to assassinate the President of the United States.

In December 1987, Fromme, serving a life sentence for the assassination attempt, escaped briefly from Federal Prison Camp, Alderson in West Virginia. She was trying to reach Manson because she heard that he had testicular cancer; she was apprehended within days.[10]: 502–511 She was released on parole from Federal Medical Center, Carswell on August 14, 2009.[83]

1980–present

[edit]Steve "Clem" Grogan, was paroled in 1985.

In a 1994 conversation with Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, Catherine Share, a one-time Manson follower, stated that her testimony in the penalty phase of Manson's trial had been a fabrication intended to save Manson from the gas chamber and that it had been given under Manson's explicit direction.[10]: 502–511 Share's testimony had introduced the copycat-motive story, which the testimony of the three female defendants echoed and according to which the Tate–LaBianca murders had been Linda Kasabian's idea.[10]: 424–433 In a 1997 segment of the tabloid television program Hard Copy, Share implied that her testimony had been given under a Manson threat of physical harm.[84] In August 1971, after Manson's trial and sentencing, Share had participated in a violent California retail store robbery, the object of which was the acquisition of weapons to help free Manson.[10]: 463–468

In January 1996, a Manson website was established by latter-day Manson follower George Stimson, who was helped by Sandra Good. Good had been released from prison in 1985, after serving 10 years of her 15-year sentence for the death threats.[10]: 502–511 [85]

In a 1998–1999 interview in Seconds magazine, Bobby Beausoleil rejected the view that Manson ordered him to kill Gary Hinman.[29] He stated that Manson did come to Hinman's house and slash Hinman with a sword, which he had previously denied in a 1981 interview with Oui magazine. Beausoleil stated that when he read about the Tate murders in the newspaper, "I wasn't even sure at that point—really, I had no idea who had done it until Manson's group were actually arrested for it. It had only crossed my mind and I had a premonition, perhaps. There was some little tickle in my mind that the killings might be connected with them ..." In the Oui magazine interview, he had stated, "When the Tate–LaBianca murders happened, I knew who had done it. I was fairly certain."[15]: 433

William Garretson, once the young caretaker at 10050 Cielo Drive, indicated in a program (The Last Days of Sharon Tate) broadcast on July 25, 1999 on E!, that he had, in fact, seen and heard a portion of the Tate murders from his location in the property's guest house. This corroborated the unofficial results of the polygraph examination that had been given to Garretson on August 10, 1969, and that had effectively eliminated him as a suspect. The LAPD officer who conducted the examination had concluded Garretson was "clean" on participation in the crimes but "muddy" as to his having heard anything.[10]: 28–38

It was announced in early 2008 that Susan Atkins was suffering from brain cancer.[86] An application for compassionate release, based on her health status, was denied in July 2008,[86] and she was denied parole for the 18th and final time on September 2, 2009.[87] Atkins died of natural causes 22 days later, on September 24, 2009, at the Central California Women's facility in Chowchilla.[88][89]

In a January 2008 segment of the Discovery Channel's Most Evil, Barbara Hoyt said that the impression that she had accompanied Ruth Ann Moorehouse to Hawaii just to avoid testifying at Manson's trial was erroneous. Hoyt said she had cooperated with the Family because she was "trying to keep them from killing my family". She stated that, at the time of the trial, she was "constantly being threatened: 'Your family's gonna die. [The murders] could be repeated at your house.'"[90]

On March 15, 2008, the Associated Press reported that forensic investigators had conducted a search for human remains at Barker Ranch the previous month. Following up on longstanding rumors that the Family had killed hitchhikers and runaways who had come into its orbit during its time at Barker, the investigators identified "two likely clandestine grave sites ... and one additional site that merits further investigation."[91] Though they recommended digging, CNN reported on March 28 that the Inyo County sheriff, who questioned the methods they employed with search dogs, had ordered additional tests before any excavation.[92] On May 9, after a delay caused by damage to test equipment,[93] the sheriff announced that test results had been inconclusive and that "exploratory excavation" would begin on May 20.[94] In the meantime, Charles "Tex" Watson had commented publicly that "no one was killed" at the desert camp during the month and a half he was there, after the Tate–LaBianca murders.[95][96] On May 21, after two days of work, the sheriff brought the search to an end; four potential gravesites had been dug up and had been found to hold no human remains.[97][98]

In September 2009, The History Channel broadcast a docudrama covering the Family's activities and the murders as part of its coverage on the 40th anniversary of the killings.[99] The program included an in-depth interview with Linda Kasabian, who spoke publicly for the first time since a 1989 appearance on A Current Affair, an American television news magazine.[99] Also included in the History Channel program were interviews with Vincent Bugliosi, Catherine Share, and Debra Tate, sister of Sharon.[100]

As the 40th anniversary of the Tate–LaBianca murders approached, in July 2009, Los Angeles magazine published an "oral history" in which former Family members, law enforcement officers, and others involved with Manson, the arrests, and the trials offered their recollections of—and observations on—the events that made Manson notorious. In the article, Juan Flynn, a Spahn Ranch worker who had become associated with Manson and the Family, said, "Charles Manson got away with everything. People will say, 'He's in jail.' But Charlie is exactly where he wants to be."[101]

Charles Manson died of a heart attack and complications from colon cancer on November 19, 2017. He was 83 years old.[102]

Bobby Beausolei was recommended parole by the California Board of Parole in 2019, a his nineteenth hearing, California Governor Gavin Newsom denied parole.

Leslie Van Houten was released on parole on July 11, 2023, at the age of 73.[103]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Juschka, Darlene M. (2023). "Chapter 4: Space Aliens and Deities Compared". In Freudenberg, Maren; Elwert, Frederik; Karis, Tim; Radermacher, Martin; Schlamelcher, Jens (eds.). Stepping Back and Looking Ahead: Twelve Years of Studying Religious Contact at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg Bochum. Dynamics in the History of Religions. Vol. 13. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 124–145. doi:10.1163/9789004549319_006. ISBN 978-90-04-54931-9. ISSN 1878-8106.

- ^ "What ever happened to the other Manson family cult members?". NBC News. November 20, 2017. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Infamous Manson Family". Biography. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Charles Manson". Biography. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Where are the Manson Family members now?". bbc.co.uk. November 20, 2017. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ "How Spahn Ranch Became a Headquarters for the Manson Family Cult". History.com. August 8, 2019. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "Susan Atkins 12/1/69 Caruso/Caballero Interview – Charles Manson Family and Sharon Tate-Labianca Murders Updates & News". Cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ "Grand Jury Testimony: Susan Atkins". Cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ Griffiths, Emmy (October 12, 2022). "How Angela Lansbury saved her daughter from Charles Manson cult". Hello!. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn Bugliosi, Vincent with Gentry, Curt. Helter Skelter — The True Story of the Manson Murders 25th Anniversary Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-393-08700-X, OCLC 15164618.

- ^ a b Emmons, Nuel. Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press, New York (1988); ISBN 0-8021-3024-0

- ^ Karpis, Alvin, with Robert Livesey. On the Rock: Twenty-five Years at Alcatraz, 1980

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sanders, Ed (2002). The Family. New York City: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-396-7.

- ^ a b Wells, Simon (April 16, 2009). Charles Manson:Coming Down Fast. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340919231.

- ^ a b Guinn, Jeff (2013). Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4518-7.

- ^ "The Six Degrees of Helter Skelter", 2009 Documentary

- ^ Griffiths, David (December 21, 1968). "Dennis Wilson: "I Live With 17 Girls"". Record Mirror.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Watkins, Paul; Soledad, Guillermo (1979). My Life with Charles Manson. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-12788-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Watson, Charles (1978). Will You Die For Me?. F.H. Revell. ISBN 0800709128.

- ^ Ott, Tim. "Charles Manson and Dennis Wilson Had a Brief and Bizarre Friendship". Biography. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ The Story of the Abandoned Movie Ranch Where the Manson Family Launched Helter Skelter Archived July 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (November 21, 2017). "Bryan Cranston had a very close run-in with Charles Manson in the 1960s". NME. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Hi-Standard Double Nine Longhorn "Buntline" Styled .22 Caliber Revolver – Charles Manson Family and Sharon Tate-Labianca Murders". Cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Manson Family Crime: The Shooting of Bernard Crowe". Findery.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Waxman, Olivia B. (July 26, 2019). "Why Did the Manson Family Kill Sharon Tate? Here's the Story Charles Manson Told the Last Man Who Interviewed Him". Time magazine. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Gary Hinman – Charles Manson Family and Sharon Tate-Labianca Murders". Cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Atkins, Susan, with Slosser, Bob (1977). Child of Satan, Child of God. Plainfield, NJ: Logos International. pp. 94–120. ISBN 0-88270-276-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The People of the State of California vs. Charles Manson, Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel (page 7)" (PDF). cielodrive.com.

- ^ a b "Beausoleil Seconds interviews". beausoleil.net. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007.

- ^ "Sharon Tate murder 10 years ago". UPI. The Hour. August 9, 1979. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Transcript of Charles Manson's 1992 parole hearing University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ^ Tata, Samantha; Kovacik, Robert (October 18, 2012). "12 Unsolved Murders Have Possible Ties to Manson Family, LAPD Says". NBC Los Angeles. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Winton, Richard (August 8, 2019). "How many more did Manson family kill? LAPD investigating 12 unsolved murders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "12 Unsolved murders link to Charles Manson". The Telegraph. October 20, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Did The Manson Family Have Other Victims?". CBS News. March 16, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Seven-year-old child finds bodies; no clue to slayer". Ukiah Daily Journal. October 14, 1968. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ More of Hollywood's Unsolved Mysteries, John Austin, SP Books, 1992, p. 240.

- ^ a b Ed Sanders, The Family, Avon Books, May 1972, p. 132.

- ^ "SUSPECTS AND SUSPICIONS". philropost.com. February 2015. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015.

- ^ "Police report progress of autopsy", Los Angeles Times, January 3, 1969, pg. D1.

- ^ "Officials Reveal Coed, 17, Was Stabbed To Death", Los Angeles Times, January 3, 1969, pg. SF1.

- ^ "Stabbing Evidence Still Out". The Dominion News. May 30, 1969. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Romano, Aja (August 7, 2019). "The Manson Family murders, and their complicated legacy, explained". Vox. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Romano, Aja (August 7, 2019). "The Manson Family murders, and their complicated legacy, explained". Vox. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Pelisek, Christine (February 22, 2019). "Did Charles Manson Have 4 More Victims? 'There's an Answer There Somewhere,' Says LAPD Detective". People. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Siemaszko, Corky (April 28, 2016). "Reet Jurvetson, Killed in 1969, Could Be a Manson Family Murder Victim". NBC. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "L.A. Cops Search for Two in 1969 Unsolved Murder of Reet Jurvetson; Say No Charles Manson Connection". People. September 8, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ "Could Canadian's Brutal 1969 Stabbing Death Be Connected to Another L.A. Cold Case?". CBC News. November 20, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Becerra, Hector; Winton, Richard (June 1, 2012). "Manson follower's tapes may yield new clues, LAPD says". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Manson Family Suspect in Killing Archived June 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Times Standard, November 14, 1972.

- ^ "Two men and three women charged with murder of 19-year-old girl", Reuters News Service, 1972.

- ^ "Ex-cons, Manson Girls Charged" Archived June 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Billings Gazette, November 15, 1972.

- ^ Eugene Oregon Register-Guard. "Producer of movie on Manson 'family' slain in Hollywood". Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ "Valley News from Van Nuys, California on September 30, 1977 · Page 64". Newspapers.com. September 30, 1977. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Identity of dead woman a mystery The Argus Fremont, June 14, 1977

- ^ Woman's murder not a sex crime The Argus Fremont, June 22, 1977

- ^ Reagan, Maureen (1989). "Paul Watkins". CNN Larry King Live (Interview). Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

Manson's alleged obsession with the Beatles is discussed at the end

- ^ a b The Influence of the Beatles on Charles Manson Archived March 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. UMKC Law. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ^ Testimony of Paul Watkins in the Charles Manson Trial Archived March 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine UMKC Law. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Capote, Truman (1987). A Capote Reader. Random House. pp. 455–462. ISBN 978-0-394-55647-5.

- ^ Bardach, Ann Louise (November 1981). "Jailhouse Interview: Bobby Beausoleil". Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e O'Neill, Tom (2019). Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-47757-4. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Schreck, Nikolas (March 1988). The Manson File. Amok Press. ISBN 0-941693-04-X.

- ^ a b Siegel, Tatiana (July 30, 2019). "Manson Victim's Friend Posits Alternative Motive: 'I Never Bought into the Race War Theory'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (1994). Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counterculture. New York City: Soft Skull Press. p. 198. ISBN 1593765037. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Dowd, Katie (November 20, 2017). "How the Beach Boys ended up recording a song written by Charles Manson". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Adamson, Nancy (June 8, 2013). "Mark Lindsay talks about new music, cats and Charlie Manson". Midland Reporter-Telegram. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Obituaries: Terry Melcher". The Daily Telegraph. November 23, 2004. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "Charles Manson". CieloDrive.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ Watson, Charles D. (April 24, 1978). "Chapter 14: Helter Skelter I (August 8–9)". In Hoekstra, Chaplain Ray (ed.). Will You Die For Me?. Cross Roads Publications, Inc. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010.

- ^ Phillips, Steven (July 12, 2019). "What Really Happened in the Manson murders? 'Chaos' casts doubt on Helter Skelter theory". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Tom (2019). Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. Little, Brown. pp. 119–139. ISBN 978-0-316-47757-4. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Report on questioning of Katherine Lutesinger and Susan Atkins October 13, 1969, by Los Angeles Sheriff's officers Paul Whiteley and Charles Guenther.

- ^ "Charles Manson facts, information, pictures – Encyclopedia.com articles about Charles Manson". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "People v. Manson". Law.justia.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Day, Buddy (December 3, 2017). Charles Manson: The Final Words. Pyramid Productions: via–Amazon Prime. Event occurs at 1:14:00-1:15:00. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Biography—"Charles Manson." A&E Network.

- ^ Schreck, Nikolas (1988). Charles Manson: Superstar. Event occurs at 46:00–47:00. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Extradition of Charles 'Tex' Watson

- ^ George, Edward; Dary Matera (1999). Taming the Beast: Charles Manson's Life Behind Bars. Macmillan. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-0-312-20970-4. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Dave. Mother Tells Life of Manson as Boy. 1971 article; retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ "18 U.S.C. § 1751". Law.cornell.edu. June 28, 2010. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "Would-Be Assassin 'Squeaky' Fromme Released from Prison". ABC. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ Catherine Share with Vincent Bugliosi, Hard Copy, 1997 Archived March 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine YouTube. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ^ "Manson's Family Affair Living in Cyberspace" Archived March 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Wired, April 16, 1997. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ a b "Ailing Manson follower denied release from prison" Archived June 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine CNN, July 15, 2008.

- ^ Netter, Sarah; Lindsay Goldwert (September 2, 2009). "Dying Manson Murderer Denied Release". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (September 26, 2009). "Susan Atkins, Manson Follower, Dies at 61". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "Manson follower Susan Atkins dies at 61". The Guardian. Associated Press. September 25, 2009. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ "Charles Manson Murders". Most Evil. Season 3. Episode 1. January 31, 2008. Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008.

- ^ "AP Exclusive: On Manson's trail, forensic testing suggests possible new grave sites". Archived March 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ More tests at Manson ranch for buried bodies Archived March 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. CNN.com. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Authorities delay decision on digging at Manson ranch Associated Press report, mercurynews.com. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Authorities to dig at old Manson family ranch Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine cnn.com. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Letter from Manson lieutenant. Archived May 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine CNN. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Monthly View – May 2008. Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Aboundinglove.org. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Four holes dug, no bodies found ... Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine iht.com. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ Dig turns up no bodies at Manson ranch site Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine CNN.com, May 21, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ a b "Manson Family member interviewed for special". Reuters. July 28, 2009. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ "Manson, About the Show". History Channel. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ Steve Oney (July 1, 2009). "Manson Web Extra: Last Words". Los Angeles magazine. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ "Death Certificate: Charles Manson Had Colon Cancer, Died Of Heart Failure". www.cbsnews.com. December 13, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Charles Manson follower Leslie van Houten released from prison a half-century after grisly killings". Associated Press. July 11, 2023.

- Manson Family

- 1967 establishments in California

- American conspiracy theorists

- Communes

- Cults