SS Imperator

SS Imperator

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SS Imperator |

| Namesake | Latin Imperator, "emperor" |

| Owner | Hamburg America Line |

| Operator | Hamburg America Line |

| Port of registry | Hamburg |

| Route | Cuxhaven - Southampton - New York |

| Builder | |

| Laid down | 18 June 1910 |

| Launched | 23 May 1912 |

| Christened | 23 May 1912 |

| Completed | June 1913 at Hamburg, Germany |

| Maiden voyage | 11 June 1913, Cuxhaven to New York Via Southampton |

| Fate | Seized as war reparations. Used as a troop transport ship for the United States from May 1919. Handed over to the Cunard Line in September 1919, and renamed as RMS Berengaria. Sold for scrap in 1939; final demolition completed in or around 1946. |

| Name | USS Imperator |

| Acquired | by the Navy 5 May 1919 at Brest, France |

| Commissioned | 5 May 1919 USS Imperator at Brest, France |

| Decommissioned | 24 November 1919 at New York City |

| Identification | ID-4080 |

| Fate | Ceded to the Cunard Line as a war prize to make up for the loss of the RMS Lusitania and later renamed Berengaria |

| Name | RMS Berengaria |

| Namesake | Berengaria of Navarre |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Route | Southampton to New York via Cherbourg. |

| Acquired | 1919 |

| Homeport | Liverpool, UK |

| Fate | Scrapped between 1939–1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Imperator-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 52,117 GRT |

| Displacement | 53,000 tons[citation needed] |

| Length | 906 ft (276 m) |

| Beam | 98 ft 3 in (29.95 m) |

| Draught | 35 ft 2 in (10.72 m) |

| Decks | 11 |

| Installed power | Steam generated at 265 psi by 46 watertube boilers of Vulcan Yarrow design, originally coal burning, later converted to oil fired in 1921. |

| Propulsion | 4 steam turbines AEG-Vulcan / Parsons direct drive on four shafts, total of 60,000 shp (45,000 kW) |

| Speed | 24 kn (44 km/h; 28 mph) max |

| Capacity |

|

| Crew | 1,180 |

SS Imperator (known as RMS Berengaria for most of her career) was a German ocean liner built for the Hamburg America Line, launched in 1912. At the time of her completion in June 1913, she was the largest passenger ship in the world, surpassing the new White Star liner Olympic.

Imperator was the first of a trio of successively larger Hamburg American liners that included Vaterland (later the United States Liner Leviathan) and Bismarck (later the White Star Line Majestic) all of which were seized as war reparations.

Imperator served for 14 months on HAPAG's transatlantic route, until the outbreak of World War I, after which she remained in port in Hamburg. After the war, she was briefly commissioned into the United States Navy as USS Imperator (ID-4080) and employed as a transport, returning American troops from Europe. Following her service with the U.S. Navy, Imperator was purchased jointly by Britain's Cunard Line and White Star Line as part of war reparations, due to the loss of the RMS Lusitania, where she sailed as the flagship RMS Berengaria for the last 20 years of her career. William H. Miller wrote that "despite her German heritage and the barely disguised Teutonic tone of her interiors, she was thought of in the 1920s and 30s as one of Britain's finest liners."[1]: 26

Construction and early career

[edit]

The first plates of the keel were laid in 1910 at the Vulcan Shipyards in Hamburg, Germany, and the ship made its maiden voyage in 1913. At 52,117 gross register tons, Imperator was the largest ship in the world until Vaterland sailed in May 1914.[2] After the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912, the shipyard added more lifeboats to Imperator to ensure there was more than enough room for all passengers and crew. In total, Imperator would carry 83 lifeboats capable of holding 5,500 people between them, 300 more than the ship's maximum capacity.[3][4]

Before her launch on 23 May 1912, Cunard announced that its new ship, RMS Aquitania, which was under construction at the time at the John Brown shipyards in Glasgow, would be longer by 1 foot (305 mm), causing dismay in Hamburg. Several weeks later, she was fitted with a figurehead, an imposing bronze eagle, increasing her length past that of Aquitania. The eagle was created by Professor Bruno Kruse of Berlin, and adorned her forepeak with a banner emblazoned with HAPAG's motto Mein Feld ist die Welt (My field is the world). The eagle's wings were torn off in an Atlantic storm during the 1914 season, after which the figurehead was removed and replaced with gold scroll-work similar to that on the stern.

During her initial sea trials, the ship ran aground on the Elbe river due to insufficient dredging and flash fire in the engine room which resulted in eight crewmen being taken to hospital. During her official trials, she suffered overheating of the turbines and some stability issues were discovered. The trials were therefore abandoned and the builders were called in to carry out emergency work. Coincidentally, 1913 was the silver jubilee year for the Kaiser, so he was going to be treated to an overnight cruise on the North Sea before the ship would make its maiden voyage. The overnight cruise was canceled; it was eventually carried out in July of that year.

Imperator left on her maiden voyage on Wednesday, 11 June 1913, with Commodore Hans Ruser in command and Hamburg-Amerika appointing four other subordinate captains for the journey to make sure that everything went smoothly. On the way, she stopped at Southampton and Cherbourg before proceeding across the Atlantic to New York, arriving on 19 June 1913. On board were 4,986 people, consisting of 859 first-class passengers, 647 second-class passengers, 648 third-class passengers, 1,495 in steerage, and 1,332 crew.[5] The ship returned to Europe from Hoboken, New Jersey, on 25 June 1913.[6]

On his first arrival, the harbor pilot assigned to bring her into the Ambrose channel, Captain George Seeth, noted that the ship listed from side to side when the helm changed the ship's direction. She was soon nicknamed "Limperator".

In October 1913, Imperator returned to the Vulcan shipyard to facilitate drastic work to improve handling and stability, as it had been discovered that her center of gravity was too high (see metacentric height). To correct the problem, the marble bathroom suites in first class were removed and heavy furniture was replaced with lightweight wicker cane. The ship's funnels were reduced in height by 9.8 ft (3 m). Finally, 2,000 tons of cement was poured into the ship's double bottom as ballast. This work cost £200,000, which had to be borne by the shipyard as part of their five-year warranty to the shipowners. At the same time, an advanced fire sprinkler system was fitted throughout the ship, as several fires had occurred on board since the vessel had entered service.

During the 1914 refit of Imperator, Commodore Ruser handed over command of the ship to Captain Theo Kier and left to take command of the new larger flagship Vaterland, which was nearing completion. Imperator returned to service on 11 March, arriving in New York five days later on the 19th.

Whereas German ships are usually referred to with the feminine article (die), Imperator was instead referred to with the masculine article (der), on the explicit personal wishes of Emperor Wilhelm II.[7]

Interiors

[edit]The architect and designer Charles Mewès was responsible for the interior design of the Imperator and his sister ships.[8] One German critic commented on the prevalence of French-style décor on the new ship:

Louis XVI seems to be the real Imperator...judging by the decorative effects with which the world's biggest liner is embellished...the ladies saloon in Colonial, the smoking room in Flemish, the swimming pool in Pompeiian, the wintergarten in Louis XVI, the parlor in Louis XVI. - Louis XVI everywhere. Where is there any manifestation of present-day German style...the company, of course, must cater to the international public, especially Americans."[9]

One contemporary review noted how the ship's "great size...has enabled her designers to allow unusual space for passenger accommodation."[10] This was echoed in The Master, Mate, and Pilot, which stated that "taking advantage of his great dimensions, the ships' public cabins, and staterooms have been made so large as to avoid any suggestion of crowding."[11] Space-saving devices like berths and folding washbasins were eliminated in the First-Class staterooms on Imperator, all of which had free-standing beds and marble-topped washstands with hot and cold running water. Almost all First-Class cabins were "outside" cabins, meaning they had portholes or windows for natural light and ventilation. Over 200 cabins were reserved for single occupancy, and 150 had en-suite bathrooms.[10] The two "Imperial" suites had 12 rooms each, including a breakfast room, private veranda, sitting room, and servants' quarters.[12]

The main First-Class dining room was on F Deck and there were two restaurants on B Deck. The main dining room could accommodate 700 diners at tables for between 2 and 8 people. The Ritz-Carlton restaurant, which was joined with a winter garden/palm court in the Directoire style, was managed by staff from the Carlton Hotel in London. There was also a Grill Room at the aft end of B Deck, a tea garden, and a Veranda café.[13] Other First-Class public rooms included a 72-foot-long lounge/ballroom, several ladies sitting rooms, and a smoking room. The Tudor style smoking room was decorated with brick from a demolished Tudor-era cottage in England.[10][14] The lounge, or "Social Hall", as it was called, was hung with Gobelins tapestries and included a stage for theatrical performances to be held. In the evening the carpet could be removed for dancing.[12][13] Off the entrance halls were amenities like a bookshop, florist, pharmacy, doctor's office, and the offices of the purser, chief steward, and baggage master.[15]

Imperator introduced a two-deck-high, Pompeiian-style swimming pool for its First-Class passengers. It was inspired by a similar swimming pool built in London in 1907 for the Royal Automobile Club, of which Charles Mewès was also one of the architects.[1]: 28 Connected to the pool were Victorian-style Turkish baths,[16] steam baths, electric baths, massage and hairdressing rooms. The gymnasium was "the largest and most luxurious that has ever been fitted up on a passenger steamer...", according to The Marine Engineering and Naval Architect.[10] For the first time on an ocean liner, Second-Class had its own gymnasium as well. Second-Class passengers also had their own smoking room, reading and writing rooms, dining room, and music room.[10]

While the Cunard refit changed plates identifying switches and valves were reversed and reinscribed in English, drains in cabin bathtubs remained marked AUF and ZU and ashtrays still read ZIGARREN.[17]

World War I and U.S. Navy service

[edit]In August 1914, as World War I began, she was laid up at Hamburg and remained inactive for more than four years, falling into dilapidation. Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Imperator was taken over by the Allied Food Shipping and Finance Agreement, and allocated to the United States for temporary use as a transport alongside Vaterland, which was now renamed SS Leviathan and bringing American service personnel home from France.[18]

She was commissioned as the USS Imperator (ID-4080) in early May 1919. After embarking 2,100 American troops and 1,100 passengers, Imperator departed Brest, France on 15 May 1919, arriving at New York City one week later. Operating with the Cruiser and Transport Force from 3 June to 10 August, she made three cruises from New York to Brest, returning over 25,000 troops, nurses, and civilians to the United States.

While en route to New York City on 17 June, Imperator assisted the Jeanne d'Arc, which had broken down in the Atlantic Ocean. The then president-elect of Brazil Epitácio Pessoa was on board Jeanne d'Arc and Imperator received him and his party for transport to the United States, arriving there several days later.[19]

Decommissioned at Hoboken, New Jersey in early 1919, Imperator was transferred to the British Shipping Controller on 20 September, and it was decided that Cunard would operate her. Captain Charles A. Smith and a full crew were sent out to New York on Carmania the new operators and the official handover from the British Shipping Controller to Cunard took place on 24 November. Imperator was then transferred to Cunard's Pier 54 for Cunard service.

Cunard service as Berengaria

[edit]

The ship arrived at Southampton on Sunday 10 December 1919 and then proceeded to Liverpool for what was planned to be a quick overhaul (he was scheduled to leave on his first voyage for the new owners on 10 January 1920). Upon inspection, the ship was found to be in poor condition. During dry-docking on 6 January, it was found that the ship's rudder had a piece missing and the propellers were suffering from erosion on their leading edges. These issues were attended to while the ship was refurbished with items borrowed from the Cunard vessels Transylvania and Carmania.[20]

Due to the extent of the work that had to be carried out, Imperator remained at Liverpool until 21 February and during this time the company's annual dinner was held on board before the ship returned to service on the North Atlantic.[20] On 2 March 1920, the ship left New York, taking nine days to reach Southampton. During the voyage, Imperator developed a severe list that was found to be caused by a faulty ash ejector. Cunard decided that the ship was in need of a major overhaul and she was withdrawn from service.[20]

Sir Arthur Rostron of the RMS Titanic passenger rescue fame and former captain of Carpathia took command of Imperator in July 1920. The following year both Imperator and Aquitania were sent to Armstrong Whitworth shipyards to be converted from coal firing to oil.[20]

The ship was renamed after the English queen Berengaria of Navarre, wife of Richard the Lionheart, in February 1921. The name deviated from the usual Cunard practice of naming ships after Roman provinces, but still retained the "-ia" suffix that was typically seen with other Cunard ships at the time.

In September 1925, a security alert at sea was triggered when the Cunard company offices in New York received a message stating there was a bomb aboard Berengaria; the vessel was then 1,200 miles out from New York, bound for Southampton. The ship was searched although the passengers and most crew were not informed about the reason. A fire drill was held just before the supposed time of detonation, so passengers could be placed close to their lifeboat stations without arousing suspicion. The bomb threat failed to materialize.[21]

On 11 May 1932, Berengaria ran aground in the Solent. She was refloated an hour later.[22]

In May 1934, Berengaria was again in the headlines when she ran aground on mud banks at Calshot on the Solent. She was pulled free by four tugs from Southampton. The vessel suffered no damage and the incident did not affect her sailing schedule.[20][23]

Despite her German heritage, Berengaria served as flagship of the Cunard fleet until replaced by her sister ship, RMS Majestic (also German: ex-SS Bismarck), in 1934 after the merger of Cunard with White Star Line.[23] In later years, Berengaria was used for discounted Prohibition-dodging cruises, which earned her jocular nicknames like Bargainaria and Boringaria.[24]

Toward the end of her service life, the ship suffered several electrical fires caused by aging wiring, and Cunard-White Star opted to retire her in 1938. She was sold to Sir John Jarvis, who had also purchased Olympic, to provide work for unemployed shipbuilders in Jarrow, County Durham.[23] Berengaria sailed for the River Tyne under the command of Captain George Gibbons to be scrapped down to the waterline. Due to the size of the vessel and the outbreak of the Second World War, the final demolition took place only in 1946.

Gallery

[edit]-

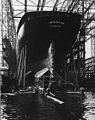

The stern of the Imperator prior to launch

-

First Class Main Staircase of Imperator.

-

USS Imperator (ID-4080), at left, and USS Leviathan (ID-1326) at Hoboken, New Jersey.

-

Imperator's turbines under construction at Vulcan, Hamburg. Note workmen, center right, for size comparison.

-

Advertisement by Hamburg-American Line in American Homes and Gardens magazine, 1913

References

[edit]- ^ a b William H. Miller (2001). Picture History of British Ocean Liners: 1900 to the Present. Dover Publications. OCLC 46462869.

- ^ "Imperator". AtlanticLiners.com. 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Thomas Kepler (2021). The Ile de France and the Golden Age of Transatlantic Travel. Lyons Press. p. 74. OCLC 1264173498.

- ^ "Some Facts Regarding Size of Marine Marvel, Imperator". Railway and Marine News. 1913. pp. 20–21.

- ^ "Big Ship, Nearing New York, Behaves Admirably on Trip". The New York Times via Marconi Wireless. 16 September 1913. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

Never before were there so many persons on one ship as are on the Imperator. The exact number is 4,986, consisting of 859 first-class passengers, 647 second-class, 648 third-class, 1,495 in steerage, and 1,332 in the crew.

- ^ "Imperator Starts Return Trip To-day. Begins First Voyage to the Eastward with More Than 1,000 in Cabins". The New York Times. 15 June 1913. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

The new Hamburg-American liner Imperator, the world's biggest transatlantic steamship, will sail on his first eastward voyage across the Atlantic at 11 o'clock this morning. The great liner when he backs out from his Hoboken berth into the river will have on board more than 1,000 cabin passengers, of whom over 600 will be in the first cabin.

- ^ Biefang, Andreas; Epkenhans, Michael; Tenfelde, Klaus. Das politische Zeremoniell im Deutschen Kaiserreich 1871–1918 (in German). p. 202. OCLC 297198603.

- ^ James Stevens Curl (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 484. OCLC 64585874.

- ^ Rotka, William (2018). "Building Luxurious Ocean Liners for the Transatlantic Elite in the Early Twentieth Century", Yearbook of Transnational History. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; pg. 120. OCLC 1045186146

- ^ a b c d e "The Marine Engineer & Naval Architect". July 1913. pp. 467–468.

- ^ "S.S. "Imperator" The World's Largest Ship". The Master, Mate, and Pilot. June 1913. p. 65.

- ^ a b "S.S. "Imperator" The World's Largest Ship". The Master, Mate, and Pilot. June 1913. pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b "The Hamburg-Amerika Liner "Imperator"". Engineering: An Illustrated Weekly Journal. 20 June 1913. pp. 827–828.

- ^ "Some Facts Regarding Size of Marine Marvel, Imperator". Railway and Marine News. 1913. p. 19.

- ^ "The Marine Engineer & Naval Architect". July 1913. p. 467.

- ^ Shifrin, Malcolm (2015). Victorian Turkish baths. Swindon: Historic England. pp.257—258 OCLC 929684255

- ^ Maxtone-Graham, John (1997). The Only Way to Cross. Barnes & Noble Books. p. 165. ISBN 0760706379.

- ^ "PESSOA TRANSFERS TO TRANSPORT AT SEA; Imperator Takes Brazil's President from Disabled French Cruiser in Midocean". The New York Times. 19 June 1919. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "SS Imperator / RMS Berengaria". Ocean-Liners.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ "Bomb hoax on the liner Berengaria". The Manchester Guardian. 25 September 1925. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ "The Berengaria aground". The Times. No. 46131. London. 12 May 1932. col C, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Berengaria". Chris' Cunard Page. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Layton, J. Kent (2013). "Imperator/Berengaria". The Edwardian Superliners: A Trio of Trios (2nd ed.). Amberley. OCLC 851154660.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Further reading

[edit]- The Hamburg-American Company's New 50,000-Ton Liner (International Marine Engineering feature article, August 1912, pp. 301–305, with launch photos & engineering details.)

- SS Imperator / RMS Berengaria[usurped]

- Atlantic Liners: A Trio of Trios, by J. Kent Layton

- Ocean Liners, by Oliver le Goff

- The Beautiful and Damned, by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Imperator/Berengaria, by Les Streater

External links

[edit]- S.S. Imperator at Flickr via Library of Congress

- S.S. Imperator (German Passenger Liner, 1913) – Served as USS Imperator (ID # 4080) in 1919. – Later the British passenger liner Berengaria

- USS Imperator (ID # 4080), 1919–1919.

- Photo gallery of Imperator at NavSource Naval History

- Imperator / Berengaria Home at Atlantic Liners.

- Ship's page at ocean-liners.com[usurped]

- The Ultimate Imperator

- Chris' Cunard Page

- Final sailing to Sir John Jarvis's scrapyard; Jarow

- Passenger ships of the United Kingdom

- Ships built in Hamburg

- Ships of the Cunard Line

- Ships of the Hamburg America Line

- Steamships of Germany

- Steamships of the United Kingdom

- Steamships of the United States

- Transports of the United States Navy

- World War I auxiliary ships of the United States

- 1912 ships

- Passenger ships of Germany

- Imperator-class ocean liners

- Maritime incidents in 1932