Beren and Lúthien

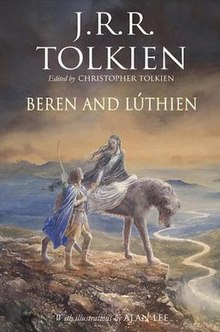

Front cover of the 2017 hardback edition | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Illustrator | Alan Lee |

| Cover artist | Alan Lee |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| Published | 2017[1] |

| Publisher | HarperCollins Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 297 |

| ISBN | 978-0-00-821419-7 |

| Preceded by | The Children of Húrin |

| Followed by | The Fall of Gondolin |

Beren and Lúthien is a 2017 compilation of multiple versions of the epic fantasy Lúthien and Beren by J. R. R. Tolkien, one of Tolkien's earliest tales of Middle-earth. It is one of what he called the three Great Tales in his legendarium. Edited by Christopher Tolkien, it tells the story of the love and adventures of the mortal Man Beren and the immortal Elf-maiden Lúthien. Tolkien wrote several versions of their tale, the last in The Silmarillion, and it is mentioned in The Lord of the Rings at the Council of Elrond. The action takes place during the First Age of Middle-earth, about 6,500 years before the events of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien found the inspiration for many of the ideas presented in the tale in his love for his wife Edith, and after her death had "Lúthien" engraved on her tombstone, and later "Beren" on his own.

Narrative

[edit]Beren, son of Barahir, cut a Silmaril from Morgoth's crown as the bride price for Lúthien, daughter of the Elf-king Thingol and Melian the Maia. His hand was cut off with a Silmaril in it; later he was killed by Carcharoth, the wolf of Angband, but alone of mortal Men returned from the dead. He lived then with Lúthien on Tol Galen in Ossiriand, and fought the Dwarves at Sarn Athrad. He was the great-grandfather of Elrond and Elros, and thus the ancestor of the Númenórean kings. After the fulfilment of the quest of the silmaril and Beren's death, Lúthien chose to become mortal and to share Beren's fate.[T 1]

Development

[edit]The first version of the story is The Tale of Tinúviel, written in 1917 and published in The Book of Lost Tales. During the 1920s, Tolkien started to reshape the tale into an epic poem, The Lay of Leithian. He never finished it, leaving three of seventeen planned cantos unwritten. After his death it was published in The Lays of Beleriand. The latest version of the tale is told in prose form in one chapter of The Silmarillion and is recounted by Aragorn in The Fellowship of the Ring. Some early versions of the story, published in the standalone book in 2017, described Beren as a Noldorin Elf as opposed to a Man.[T 2]

Publication

[edit]The book was edited by Christopher Tolkien and illustrated with nine full-colour plates by Alan Lee.[1][2][3] The story is one of three within The Silmarillion that Tolkien believed warranted their own long-form narratives, the other two being The Children of Húrin and The Fall of Gondolin. The book features different versions of the story, showing the development of the tale over time. It is restored from Tolkien's manuscripts and presented for the first time as a single more or less continuous narrative, using the ever-evolving materials that make up "The Tale of Beren and Lúthien". It does not contain every version or edit to the story, but those Christopher Tolkien believed would offer the most clarity and minimal explanation:

I have tried to separate the story of Beren and Tinúviel (Lúthien) so that it stands alone, so far as that can be done (in my opinion) without distortion. On the other hand, I have wished to show how this fundamental story evolved over the years.[T 3]

- The purpose of this book, then, is altogether different from that of the volumes of The History of Middle-earth from which it is derived. It is emphatically not intended as an adjunct to those books. It is an attempt to extract one narrative element from a vast work of extraordinary richness and complexity; but that narrative, the story of Beren and Lúthien, was itself continually evolving, and developing new associations as it became more embedded in the wider history. The decision of what to include and what to exclude of that ancient world 'at large' could only be a matter of personal and often questionable judgement: in such an attempt there can be no attainable 'correct way'. In general, however, I have erred on the side of clarity, and resisted the urge to explain, for fear of undermining the primary purpose and method of the book.[T 4]

Approach

[edit]The book starts with the most complete version of the beginning of the tale, "The Tale of Tinúviel" as told in The Book of Lost Tales, with only slight editing of character and place names to avoid confusion with later versions. The general aspect of the story has not been modified; Beren, for example, is a Gnome (Noldo), the son of Egnor bo-Rimion, rather than the human son of Barahir. Beren's heritage switches between elf and man throughout the book, depending on which portion of the story is being told.

As Christopher Tolkien explains:

A further problem which I should mention arose from the very frequent changes of names. To follow with exactness and consistency the succession of names in texts of different dates would not serve the purpose of this book. I have therefore observed no rule in this respect, but distinguished old and new in some cases but not in others, for various reasons. In a great many cases my father would alter a name in a manuscript at some later, or even much later, time, but not consistently: for example, Elfin to Elven. In such cases I have made Elven the sole form, or Beleriand for earlier Broseliand; but in others I have retained both, as in Tinwelint/ Thingol, Artanor/ Doriath.[T 5]

Further chapters continue the story in through later poems, summaries, and prose, showing how the story evolved over time, in order of the chronology of the story itself (not necessarily the order in which the texts were written or published). These include portions of various versions of "The Lay of Leithian", The Silmarillion, and later chapters of Lost Tales.

Since J. R. R. Tolkien made many changes to the story, affecting both narrative and style, the presentation in the book is not entirely consistent. There is some overlap of details and discrepancy in continuity, but the sections attempt a complete and continuous story. Christopher Tolkien included editorial explanations and historical details to bridge between sections. Details lost in later accounts were reintroduced: such as Tevildo (who due to the nature of his introduction is treated as a separate character, rather than an early conception of Sauron), Thû the Necromancer (treated as the first appearance of Sauron), the Wicked (or "treacherous") Dwarves (one of The Hobbit's references to Lost Tales), and other terminology such as Gnome (Noldoli, later Noldorin Elf), Fay, Fairy, leprechaun, and pixie. Some of these terms appear in early editions of The Hobbit, but were dropped in later writing.

The book offers an "in-universe" perspective for the inconsistencies, as owing to the evolution of the stories told by different perspectives and voices over time, rather than simply reflecting Tolkien's changing ideas over time.

the First Age in The History of Middle-earth was in those books conceived as a history in two senses. It was indeed a history—a chronicle of lives and events in Middle-earth; but it was also a history of the changing literary conceptions in the passing years; and therefore the story of Beren and Lúthien is spread over many years and several books. Moreover, since that story became entangled with the slowly evolving Silmarillion, and ultimately an essential part of it, its developments are recorded in successive manuscripts primarily concerned with the whole history of the Elder Days.[T 6]

This book reintroduces details that were omitted in the highly edited version of The Silmarillion's "Of the Ruin of Doriath": it includes the cursed treasure of Mîm; that Doriath was betrayed from the inside; that Thingol was able to push the dwarves out of the city; and that he was later killed by an ambush of dwarves. It roughly reconciles the elements of early Lost Tales with details constructed by Guy Kay for the chapter in the Silmarillion, to bring it closer to Tolkien's intention as described in The War of the Jewels:[T 7]

...there are brought to light passages of close description or dramatic immediacy that are lost in the summary, condensed manner characteristic of so much Silmarillion narrative writing; there are even to be discovered elements in the story that were later altogether lost. Thus, for example, the cross-examination of Beren and Felagund and their companions, disguised as Orcs, by Thû the Necromancer (the first appearance of Sauron), or the entry into the story of the appalling Tevildo, Prince of Cats, who clearly deserves to be remembered, short as was his literary life.[T 7]

Analysis

[edit]Tolkien based the tale of Beren and Lúthien on the classical legend of Orpheus and Eurydice in the underworld. The philologist and Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey writes that comments that Tolkien embroiders this framework with story elements from multiple folktales, myths, and legends, commenting that he "had not yet freed himself from his sources – as if trying to bring in all the older bits of literature that he liked instead of forging a story with an impetus of its own."[4]

Reception

[edit]Tolkien's biographer John Garth, writing in the New Statesman, notes that it took a century for the tale of Beren and Lúthien, mirroring the tale of Second Lieutenant Tolkien watching Edith dancing in a woodland glade far from the "animal horror" of the trenches, to reach publication. Garth finds "much to relish", as the tale changes through "several gears" until finally it "attains a mythic power". Beren's enemy changes from a cat-demon to the "Necromancer" and eventually to Sauron. Garth comments that if this was supposed to be the lost ancestor of the Rapunzel fairytale, then it definitely portrays a modern "female-centred fairy-tale revisioning" with a Lúthien who may be fairer than mortal tongue can tell, but is also more resourceful than her lover.[5]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch 19 "Of Beren and Lúthien"

- ^ Tolkien 1984b, ch. 1 "The Tale of Tinúviel": "Now Beren was a Gnome, son of Egnor the forester"

- ^ Tolkien 2017, Kindle 86-88

- ^ Tolkien 2017, Kindle 129-135

- ^ Tolkien 2017, Kindle 124-129

- ^ Tolkien 2017, Kindle 74-79

- ^ a b Tolkien 2017, Kindle 95-99

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b "JRR Tolkien book Beren and Lúthien published after 100 years". BBC News. Oxford. 1 June 2017.

- ^ Flood, Alison (19 October 2016). "JRR Tolkien's Middle-earth love story to be published next year". The Guardian.

- ^ Helen, Daniel (17 February 2017). "Beren and Lúthien publication delayed".

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Garth, John (27 May 2017). "Beren and Lúthien: Love, war and Tolkien's lost tales". New Statesman. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2017). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Beren and Lúthien. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-821419-7.