Malay Indonesians

Orang Melayu Indonesia ملايو ايندونيسيا | |

|---|---|

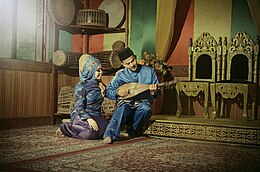

A Riau Malay couple enjoying the traditional Gambus. The background panel incorporated the palettes of Malay tricolour. | |

| Total population | |

| 8,753,791 (2010)[1][a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8,753,791 (2010) | |

| | 3,139,000 |

| | 2,880,240 |

| | 1,259,890[3] |

| | 936,000 |

| | 914,660 |

| | 600,108 |

| | 582,100 |

| | 269,240 |

| | 190,224 |

| | 165,039 |

| | 125,120 |

| | 87,222 |

| | 84,468 |

| | 64,881 |

| Languages | |

| Native Malay (Numerous vernacular Malay varieties) Also Indonesian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Malay Indonesians (Malay/Indonesian: Orang Melayu Indonesia; Jawi: اورڠ ملايو ايندونيسيا) are ethnic Malays living throughout Indonesia. They are one of the indigenous peoples of the country.[5] Indonesian, the national language of Indonesia, is a standardized form of Riau Malay.[6][7] There were numerous kingdoms associated with the Indonesian Malays along with other ethnicities in what is now Indonesia, mainly on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. These included Srivijaya, the Melayu Kingdom, Dharmasraya, the Sultanate of Deli, the Sultanate of Siak Sri Indrapura, the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, the Sultanate of Bulungan, Pontianak Sultanate, and the Sultanate of Sambas. The 2010 census states that there are 8 million Malays in Indonesia; this number comes from the classification of Malays in East Sumatra and the coast of Kalimantan which is recognized by the Indonesian government. This classification is different from the Malaysia and Singapore census which includes all ethnic Muslims from the Indonesian archipelago (inc. Acehnese, Banjarese, Bugis, Mandailing, Minangkabau and Javanese) as Malays.

History

[edit]

Indonesia is the birthplace of the Malay civilization, which is the precursor of the Malay ethnic group scattered along the east coast of Sumatra, Singapore, the Malay Peninsula, and the coast of Kalimantan. The epic literature, the Malay Annals, associates the etymological origin of "Melayu" to a small river named Sungai Melayu ('Melayu river') in Sumatra. The epic incorrectly stated that the river flowed to the Musi River in Palembang, while in reality it flowed to the Batang Hari River in Jambi.[8]: 298 The term is thought to be derived from the Malay word melaju, a combination of the verbal prefix 'me' and the root word 'laju', meaning "to accelerate", used to describe the accelerating strong current of the river.[9]

The beginning of the Common Era saw the rise of Malay states in the coastal areas of the Sumatra and Malay Peninsula; Srivijaya, Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom, Gangga Negara, Langkasuka, Kedah, Pahang, the Melayu Kingdom and Chi Tu. Between the 7th and 13th centuries, many of these small, often prosperous peninsula and Sumatran maritime trading states, became part of the mandala of Srivijaya,[10] a great confederation of city-states centred in Palembang.[11]

Srivijaya's influence spread over all the coastal areas of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, western Java and western Borneo, as well as the rest of the Malay Archipelago. Enjoying both Indian and Chinese patronage, its wealth was gained mostly through trade. At its height, the Old Malay language was used as its official language and became the lingua franca of the region, replacing Sanskrit, the language of Hinduism.[12]

The glory of Srivijaya however began to wane after the series of raids by the Tamil Chola dynasty in the 11th century. After the fall of Srivijaya in 1025 CE, the Malayu kingdom of Jambi, Sumatra, became the most dominant Malay state of the region.[13] By the end of the 13th century, the remnants of the Malay empire in Sumatra was finally destroyed by the Javanese invaders during the Pamalayu expedition (Pamalayu means "war against the Malays").[14]

In 1299, through the support of the loyal servants of the empire, the Orang laut, a prince of Palembang origin, Sang Nila Utama established the Kingdom of Singapura in Temasek.[15] His dynasty ruled the island kingdom until the end of the 14th century, when the polity once again faced the wrath of Javanese invaders. In 1400, his great-great-grandson, Parameswara, headed north and established the Malacca Sultanate.[16] The new kingdom succeeded Srivijaya and inherited much of the royal and cultural traditions, including a large part of the territories of its predecessor.[17][18][19]

By the 15th century, the Malacca Sultanate, whose hegemony reached over much of the western Malay Archipelago, had become the centre of Islamisation in the east. As a Malaccan state religion, Islam brought many great transformation into the Malaccan society and culture, and It became the primary instrument in the evolution of a common Malay identity. The Malaccan era witnessed the close association of Islam with Malay society and how it developed into a definitive marker of Malay identity.[20][21][22][23] Over time, this common Malay cultural idiom came to characterise much of the Malay Archipelago through the Malayisation process. The expansion of Malaccan influence through trade and Dawah brought with it together the Classical Malay language,[24] the Islamic faith,[25] and the Malay Muslim culture;[26] the three core values of Kemelayuan ("Malayness").[27] the course of history, the term "Malay" has been extended to other ethnic groups within the "Malay world"; this usage is nowadays largely confined to Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore,[28] where descendants of immigrants from these ethnic group are termed as anak dagang ("traders") and who are predominantly from the Indonesian archipelago.

Contrary to Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore, Malayness has no special position in Indonesian state ideology, except as one of the constituent regional cultures — which tend to be represented on a province-by-province basis. Loyalty for a certain ethnic group was overshadowed with the new inter-ethnic loyalty, advocating the importance of the national unity and national identity of Bangsa Indonesia ("Indonesian nation") instead. Ethnic Malay is only recognised as one of myriad Indonesian ethnic groups, which enjoy equal status with other Indonesians such as Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, Dayak, Buginese, Ambonese and Papuan.

Sumatra

[edit]There are various kingdoms and sultanates related to the history of the Malay people and other ethnicities on the island of Sumatra, such as Melayu Kingdom, Srivijaya, Dharmasraya, Sultanate of Deli, Sultanate of Siak Sri Indrapura, Asahan Sultanate, Riau-Lingga Sultanate, Riau Sultanate, Palembang Sultanate and the Lingga Sultanate, etc.

Kalimantan

[edit]There are various kingdoms and sultanates related to the history of the Malay people and other ethnicities on the island of Kalimantan (a.k.a. Borneo), such as Sanggau Kingdom, Pontianak Sultanate, Bulungan Sultanate, Berau Sultanate, Gunung Tabur Sultanate, Sambaliung Sultanate, Paser Sultanate, Kutai Sultanate, etc.

In the Pontianak incidents during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, the Japanese massacred most of the Malay elite and beheaded all of the Malay Sultans in Kalimantan.

During the Fall of Suharto, there was a resurgence in Malay nationalism and identity in Kalimantan and ethnic Malays and Dayaks in Sambas massacred Madurese during the Sambas riots.

Languages

[edit]

Sumatra is the homeland of the Malay languages, which today spans all corners of Southeast Asia. The Indonesian language, which is the country's official language and lingua franca, was based on Riau Malay, which despite its common name is not based on the vernacular Malay dialects of the Riau Islands, rather it represents a form of Classical Malay as used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The Malay language has a long history, which has a literary record as far back as the 7th century AD. A famous early Malay inscription, the Kedukan Bukit Inscription, was discovered by the Dutchman M. Batenburg on 29 November 1920, at Kedukan Bukit, South Sumatra, on the banks of the Tatang river, a tributary of the Musi River. It is a small stone of 45 by 80 cm. It is written in Old Malay, a possible ancestor of today's Malay language and its variants. Most Malay languages and dialects spoken in Indonesia are mutually unintelligible with Standard Indonesian. The most widely spoken are Palembang Malay (3.2 million), Jambi Malay (1 million), Bengkulu Malay (1.6 million) and Banjarese (4 million) (although not considered to be a dialect of Malay by its speakers; its minor dialect is typically called Bukit Malay). Speakers of unintelligible Malay dialects speak standard Indonesian as a lingua franca. Besides the proper Malay languages, there are several languages closely related to Malay such as Minangkabau, Kerinci, Kubu and others. These languages are closely related to Malay, but their speakers do not consider their languages to be Malay. There are many Malay-based creoles spoken in the country especially in eastern Indonesia due to contacts from the western part of Indonesia and during colonial rule where Malay replaced Dutch as a lingua franca. The most well-known Malay creoles in Indonesia are Ambonese Malay, Betawi, Manado Malay and Papuan Malay.

Sub-ethnic groups of Indonesian Malays

[edit]

Malay ethnic groups in Indonesia

[edit]

The Malay people in Indonesia fall into various sub-ethnicities with each having its own distinct linguistic variety, history, clothing, traditions, and a sense of common identity. According to Ananta et al. 2015,[30] Malay Indonesians include:

Sumatra

[edit]- Langkat Malays

- Deli Malays

- Asahan Malays

- Riau Malays

- Jambi Malays

- Banyuasin Malays

- Lahat Malays

- Lematang people

- Kikim people

- Pasemah people

- Gumai people

- Kisam people

- Serawai people

- Semendo people

- Semidang people

- Lintang people

- Bengkulu Malays

Kalimantan

[edit]Bali

[edit]Sulawesi

[edit]Aboriginal Malays

[edit]

Notable Malay Indonesians

[edit]Literature

[edit]- Andrea Hirata, Indonesian author

- Raja Ali Haji, a 19th-century historian, member of the royal house of Riau-Lingga and Selangor and National Hero of Indonesia

- Tere Liye, Indonesian author

Royalty

[edit]

- Tuanku Sultan Otteman II – a former Sultan of Deli, in which the kingdom's capital was Medan, in North Sumatra.

- Sultan Ma'mun Al Rashid Perkasa Alamyah – 9th Sultan of Deli Sultanate

- Sultan Hamid II – former Sultan of the Pontianak Sultanate

- Pangeran Ratu Winata Kusuma of Sambas – heir to the Sultanate of Sambas

- Sultan Syarif Kasim II – 12th Sultan of Siak Sultanate

Politics

[edit]- Marzuki Alie – speaker of the People's Representative Council, 2009–2014 term

- Hatta Rajasa – the Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs in the Second United Indonesia Cabinet. Previously, he was the State Secretary, Minister of Transport and Minister for Research and Technology in the Mutual Assistance Cabinet (2001–2004).

- Tito Karnavian - the Minister of Minister of Home Affairs. Previously, he was the chief of Indonesian National Police from 2016 to 2019, and chief of the National Counter Terrorism Agency in 2016

- Amir Hamzah – an Indonesian poet and National Hero of Indonesia.

- Hamzah Haz – an Indonesian politician. He is the head of the United Development Party (PPP) and served as the ninth Vice-president from 2001 until 2004.

- Alex Noerdin – the 15th Governor of South Sumatra

- Muhammad Lukman Edy – the former Minister for Acceleration of Disadvantaged Regions in 2007/2009

- Muhammad Sani – the 2nd Governor of Riau Island

- Tengku Rizal Nurdin – the 13th Governor of North Sumatra

- Tengku Erry Nuradi - the 17th Governor of North Sumatra

- Rusli Zainal – the 13th Governor of Riau

- Tantowi Yahya – Indonesian TV presenter turned politician.

Entertainment

[edit]- Carissa Putri – Indonesian model and actress

- Revalina Sayuthi Temat – Indonesian actress, popularly known for her work in Bawang Merah Bawang Putih

- Titi Kamal – prominent Indonesian actress and singer

- Farah Quinn – celebrity chef

- Iyeth Bustami – Indonesian dangdut singer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The figure is based on the ethnic classification presented in Ananta et al. 2015, which includes figures for every groups with "Malay" in their names as well as Jambi, Bengkulu, Serawai, Semendo peoples, but excludes figures for Palembang, Bangka, and Belitung peoples.[2]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Ananta et al. 2015, p. 119.

- ^ Ananta et al. 2015, pp. 35–36, 42–43.

- ^ "Propinsi Kalimantan Barat - Dayakologi". Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono. Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015. p. 273.

- ^ "Badan Kesatuan Bangsa dan Politik". kesbangpol.riau.go.id. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ Sneddon 2003, The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society, p. 69–70

- ^ Kamus Saku Bahasa Indonesia, p. 272, PT Mizan Publika, ISBN 9789791227834

- ^ Reid, Anthony (October 2001). "Understanding Melayu (Malay) as a Source of Diverse Modern Identities". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (3): 295–313.

- ^ Melebek & Moain 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Sabrizain. "Early Malay kingdoms". Sejarah Melayu. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Munoz 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Zaki Ragman 2003, pp. 1–6

- ^ Miksic & Goh 2017, p. 359, 397, 398.

- ^ Miksic & Goh 2017, p. 464.

- ^ Ministry of Culture 1973, p. 9.

- ^ Cœdès 1968, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Alexander 2006, p. 8 & 126.

- ^ Stearns 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Wolters 1999, p. 33.

- ^ Barnard 2004, pp. 7 & 60.

- ^ Andaya & Andaya 1984, p. 55.

- ^ Mohd Fauzi Yaacob 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Abu Talib Ahmad & Tan 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Sneddon 2003, p. 74.

- ^ Milner 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Esposito 1999.

- ^ Mohamed Anwar Omar Din 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Milner 2010, p. 10 & 185.

- ^ Guy, John (2014). Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 21. ISBN 9781588395245.

- ^ Ananta et al. 2015, pp. 42–43.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abu Talib Ahmad; Tan, Liok Ee (2003), New terrains in Southeast Asian history, Singapore: Ohio University press, ISBN 978-9971-69-269-8

- Alexander, James (2006), Malaysia Brunei & Singapore, New Holland Publishers, ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3

- Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8.

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Yuzon (1984), A History of Malaysia, London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-27672-3

- Barnard, Timothy P. (2004), Contesting Malayness: Malay identity across boundaries, Singapore: Singapore University press, ISBN 978-9971-69-279-7

- Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Esposito, John L. (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510799-9

- Melebek, Abdul Rashid; Moain, Amat Juhari (2006), Sejarah Bahasa Melayu ("History of the Malay Language"), Utusan Publications & Distributors, ISBN 978-967-61-1809-7

- Miksic, John N.; Goh, Geok Yian (2017), Ancient Southeast Asia, London: Routledgeg

- Milner, Anthony (2010), The Malays (The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4443-3903-1

- Ministry of Culture, Singapore (1973), "Singapore: facts and pictures", Singapore Facts and Figures, ISSN 0217-7773

- Mohamed Anwar Omar Din (2011), Asal Usul Orang Melayu: Menulis Semula Sejarahnya (The Malay Origin: Rewrite Its History), Jurnal Melayu, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, archived from the original on 9 December 2019, retrieved 4 June 2012

- Mohd Fauzi Yaacob (2009), Malaysia: Transformasi dan perubahan sosial, Kuala Lumpur: Arah Pendidikan Sdn Bhd, ISBN 978-967-323-132-4

- Munoz, Paul Michel (2006), Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, ISBN 978-981-4155-67-0

- Sneddon, James N. (2003), The Indonesian language: its history and role in modern society, University of New South Wales Press, ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8

- Stearns, Peter N. (2001), The Encyclopedia of World History, vol. 1, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4

- Wolters, Oliver William (1999), History, culture, and region in Southeast Asian perspectives, Singapore: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications, ISBN 978-0-87727-725-5

- Zaki Ragman (2003), Gateway to Malay culture, Singapore: Asiapac Books Pte Ltd, ISBN 978-981-229-326-8