Ben Bagdikian

Ben Bagdikian | |

|---|---|

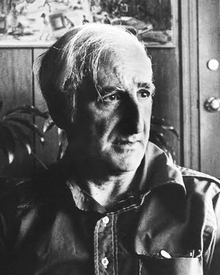

Bagdikian in 1976 | |

| Born | Ben-Hur Haig Bagdikian January 30, 1920 Marash, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | March 11, 2016 (aged 96) Berkeley, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Clark University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1947–1990 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1942−1946[1] |

| Rank | |

Ben-hur Haig Bagdikian[2] (January 30, 1920 – March 11, 2016) was an American journalist, news media critic and commentator,[3] and university professor. An Armenian genocide survivor, he moved to the United States as an infant and began a journalism career after serving in World War II. He worked as a local reporter, investigative journalist and foreign correspondent for The Providence Journal. During his time there, Bagdikian won a Peabody Award and a Pulitzer Prize. In 1971, he received parts of the Pentagon Papers from Daniel Ellsberg and successfully persuaded The Washington Post to publish them despite objections and threats from the Richard Nixon administration. He later taught at the University of California, Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and served as its dean from 1985 to 1988.

Bagdikian was a critic of the news media.[4] His 1983 book The Media Monopoly, warning about the growing concentration of corporate ownership of news organizations, went through several editions and influenced, among others, Noam Chomsky. He has been hailed for his ethical standards and has been described by Robert W. McChesney as one of the finest journalists of the 20th century.

Personal life

[edit]Background

[edit]Ben-Hur Haig Bagdikian,[5][6] born in Marash, Ottoman Empire, on January 30, 1920, was the fifth and youngest child of Aram Toros "Theodore" Bagdikian[7] (1882−1957) and Dudeh "Daisy" Uvezian (1886−1923).[8] He had four sisters.[9] His mother's family was well-off, while his father came from a peasant family. He did graduate work at the American University of Beirut.[7] The family was mostly based in Tarsus, where his father taught physics and chemistry at St. Paul's College in Tarsus, run by Boston Congregationalists.[6][10][7] His family knew English well.[11] His father also spoke Armenian, Turkish, Arabic, and learned the Biblical languages.[12]

His family left Marash on February 9, 1920, just ten days after Ben was born. They left during the Armenian genocide,[8] as Turkish forces reached the city, while the French retreated.[13] While escaping persecution, Bagdikian was dropped in the snow in the mountains while the family was climbing. Only an infant, he was thought to be dead. He was picked up when he began to cry.[5][14] They arrived, first, in Boston and subsequently settled in Stoneham, Massachusetts. His father was a pastor at several Armenian churches in the Boston area (in Watertown, Cambridge) and Worcester. He had taken courses at the Harvard Divinity School and had been ordained.[15] When Bagdikian was three years old his mother was diagnosed with tuberculosis almost immediately after arrival in Boston and died three years later, after spending some time hospitalized in sanatoriums.[6][16][17]

Bagdikian was known throughout his life as Ben, though his baptismal name was Ben-Hur, after the Christian-themed historical novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by Lew Wallace.[14] Bagdikian grew up during the Great Depression, which, according to Robert D. McFadden, enforced a "passion for social justice that shaped his reporting."[8] He described himself as an "Armenian overlaid by, of all things, the culture of New England Yankee."[14]

Religion

[edit]Due to his father's role, Bagdikian regularly attended sermons and "disliked the avenging God of the Old Testament and was outraged when Abraham was prepared to obey the order to sacrifice his son as a gesture of faith."[10] Later in adulthood, Bagdikian became a member of the First Unitarian Church of Providence, a Unitarian Universalist congregation in Rhode Island.[10]

Education and military service

[edit]Bagdikian initially aspired to become a doctor because of his mother's illness and his father's collection of books on pulmonary diseases that he read.[18] He graduated from Stoneham High School in 1937.[19] He thereafter attended Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, as a pre-medical student.[10] He was editor of The Clark News, the college newspaper. He renamed it to The Clark Scarlet, based on the school's colors. The university president, Wallace Walter Atwood, suspected it was too closely associated with communism.[20][21] Having taken many chemistry courses he sought to apply for a job as a chemist upon graduating from Clark in 1941.[19][14] He had the opportunity to work as a lab assistant at Monsanto in Springfield, Massachusetts.[22]

He served as a navigator (first lieutenant) in the United States Army Air Forces from May 1942 to January 1946.[1][8] He had volunteered to join the Air Forces immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.[23]

Marriages

[edit]Bagdikian married Elizabeth (Betty) Ogasapian in 1942, with whom he had two sons: Aram Christopher "Chris" Bagdikian (1944−2015) and Frederick, Jr. "Eric" Bagdikian (born 1951). They divorced in 1972.[6][8] His second marriage, to Betty Medsger, a Washington Post reporter, ended in divorce as well.[5] His third wife was Marlene Griffith (born Marie Helene Ungar in Vienna), whom he married in 1983.[24][6][8]

Death

[edit]Bagdikian died at his home in Berkeley, California, on March 11, 2016, aged 96.[8][25] A memorial service was held at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Berkeley on June 2, 2016.[26]

Career

[edit]Throughout his career, Bagdikian contributed to more than 200 national magazines and journals.[27]

During his college years Bagdikian worked as a reporter for the Worcester Gazette and Springfield Morning Union.[18][28] After World War II he briefly joined the staff of Flying Traveler, a magazine for private flying in New York.[29]

The Providence Journal

[edit]Bagdikian began working for the Providence Journal in 1947 as a reporter and Washington bureau chief. He also served as a local reporter. Bagdikian and Journal editor and publisher Sevellon Brown won a Peabody Award in 1951 for their "most exacting, thorough and readable check-up of broadcasts" of Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, and Fulton Lewis, leading TV and radio commentators.[14][5] He was a member of the staff that received the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting, Edition Time for coverage of a bank robbery in East Providence (including an ensuing police chase and hostage standoff) that resulted in the death of a patrolman.[30][8] Bagdikian later described the paper as one of the better papers, besides their pro-Republican and anti-union editorials.[31]

As a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, he covered the Suez Crisis in the fall of 1956 riding with an Israeli tank crew.[8] In 1957, Bagdikian covered the civil rights movement, especially the crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas.[32] In the fall of that year he traveled to the South with black reporter James "Jim" N. Rhea[30][14] to cover the widespread discontent of the whites with the Supreme Court order to desegregate public schools.[33]

Freelance

[edit]Bagdikian began a freelance career after leaving the Providence Journal in 1961.[14] He researched media matters at the Library of Congress with the Guggenheim Fellowship he was awarded in 1961.[34][28] Subsequently, he was a Washington-based contributing editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1963 to 1967. He also wrote for The New York Times Magazine when he focused on social issues, such as poverty, housing, and migration. Bagdikian researched news media at the RAND Corporation in 1969–70 and published a book titled The Information Machines: Their Impact on Men and the Media in 1971․ Edwin B. Parker of Stanford University praised the report for its readability, and breadth and depth of Bagdikian's "perception of technological and economic trends and his insight into potential social and political consequences."[35]

The Washington Post

[edit]Bagdikian joined The Washington Post in 1970 and later served as its assistant managing editor and in 1972 its second ombudsman as a representative of the readers.[8][5]

In June 1971 Bagdikian, as the assistant managing editor for national news at the Post, met with Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst and former RAND Corporation colleague, who in a Boston-area motel[36] passed him 4,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers, excerpts from which were published by The New York Times days earlier and halted by a federal judge.[5] Bagdikian flew with the Papers to Washington, where he physically presented them in large boxes to executive editor Ben Bradlee at the latter's home; he also gave the Papers to US Senator Mike Gravel on June 26 [37] in front of the Mayflower Hotel.[38][39][8][5] While the Post lawyers and management were opposed,[40] Bagdikian argued strongly in favor of publication of the documents despite pressure from the Nixon administration not to on national security grounds.[8] Bagdikian famously stated: "the (only) way to assert the right to publish is to publish."[5][41][42][43][44] The first part was published by the Post on June 18, 1971.[45] William Rehnquist phoned Post executive editor Bradlee and threatened him with prosecution if the publication of the documents was not stopped. In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court decided 6–3 that "to exercise prior restraint, the Government must show sufficient evidence that the publication would cause a 'grave and irreparable' danger."[5]

Just months after the publication of the Pentagon Papers Bagdikian became an undercover inmate at the Huntingdon State Correctional Institution, a maximum-security prison in Pennsylvania, to expose the harsh prison conditions.[8] With permission from the attorney general of Pennsylvania, he disguised himself as a murderer to observe the prison life without the knowledge of anyone inside the prison. He remained there for six days and his eight-part series on the conditions of the prison were published in the Post from January 29 to February 6, 1972.[46] He reported "widespread racial tension behind bars, outbursts of violence, open 'homosexualism' and an elaborate, yet fragile, code of etiquette." Bagdikian and Post reporter Leon Dash published the series first as a report in 1972 and later as a book (1976).[47][5]

Bagdikian left the Post in August 1972 after clashing with Bradlee "as a conduit of outside and internal complaints."[5][48]

UC Berkeley

[edit]Bagdikian wrote for the Columbia Journalism Review from 1972 to 1974.[8] He taught at University of California, Berkeley from 1976 until his retirement in 1990. He taught courses such as Introduction to Journalism and Ethics in Journalism.[49] He was the dean of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism from 1985 to 1988.[8][14] He was named Professor Emeritus upon departure.[50]

Media criticism

[edit]"Never forget that your obligation is to the people. It is not, at heart, to those who pay you, or to your editor, or to your sources, or to your friends, or to the advancement of your career. It is to the public."

In an interview with PBS's Frontline Bagdikian stated that while the First Amendment allows newspapers to print anything, especially unpopular things, newspapers have an implied moral obligation to be responsible, because of their power on popular opinion and because the First Amendment was "framed with the supposition that there would be multiple sources of information."[52]

Bagdikian was an early advocate of in-house critics, or ombudsmen in newspapers, who he believed, would "address public concerns about journalistic practices."[5] He described the treatment of news about tobacco and related health issues as "one of the original sins of the media," because "for decades, there was suppression of medical evidence ... plain suppression."[52] Bagdikian criticized the wide use of anonymous sources in news media, the acceptance of government narratives by reporters, particularly on "national security" grounds.[8] Bagdikian formulated a law, dubbed the Bagdikian Law of Journalism: "The accuracy of news reports of an event is inversely proportional to the number of reporters on the scene."[8]

He was a harsh critic of TV news and the celebrity status of news anchors, which he argued, was the "worst thing that can happen to a journalist." He noted, "The job of the celebrity is to be observed, to make sure others learn about him or her, to be the object of attention rather than an observer."[8] Bagdikian stressed the importance of local media. He argued that only locally based journalism can adequately report the local issues and candidates, otherwise "voters become captives of the only alternative information, paid political propaganda, or no information at all."[51] Regarding online journalism, Bagdikian stated that there is "lots of junk on it, but it's still an outlet for an independent with no money but plenty of ingenuity and skill, like MoveOn.org. It's not controlled by the corporations. Not yet."[14]

Bagdikian was a regular New York Times reader, and appreciated The Nation, The Progressive, alternative radio, The New York Review of Books; he also read Time and Newsweek to "get a view of the total picture most magazine readers are getting." He also occasionally read the National Review and The Weekly Standard "to know what the right is thinking." Bagdikian recommended The Nation, The Progressive and Newsweek for those who wanted to stay informed but have limited time to do so.[14]

In 1987 Bagdikian testified on the effects of profit on news reporting before the House Energy Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, along with economist John Kenneth Galbraith.[53] Both Galbraith and Bagdikian voiced their concerns about the takeover of TV networks by large corporations.[54]

Publications

[edit]Bagdikian's first book, In the Midst of Plenty: The Poor in America, was published in 1964 by Beacon Press and covered various categories of poverty in America, including the poor in Appalachia, the elderly in Los Angeles, men in flophouses in Chicago, and others.[14] His studies at the RAND Corporation produced two books: The Information Machines: Their Impact on Men and the Media and The Effete Conspiracy and Other Crimes by the Press, published by Harper & Row in 1971 and 1972, respectively.[55]

His memoir, Double Vision: Reflections on My Heritage, Life and Profession, was published by Beacon Press in 1995.[8][56]

The Media Monopoly

[edit]In 1983 Bagdikian authored a widely cited and acclaimed work,[57] The Media Monopoly, which was published by Beacon Press after it was rejected by Simon & Schuster.[58][59] Richard E. Snyder, Simon & Schuster's president, was, according to Bagdikian, "vehemently opposed to the manuscript, because, among other reasons, [Snyder] felt it made all corporations look bad."[60] The book examines the increasing concentration of the media in the US in the hands of corporate owners, which, he argued, threatened freedom of expression and independent journalism. He wrote that some 50 corporations controlled what most people in the United States read and watched.[8] Bagdikian argued that "media power is political power."[61] The book went into 5 more editions—in 1987, 1990, 1993, 1997, 2000. In 2004, The New Media Monopoly was published, essentially the 7th edition of the original.[14] In 2000 Bagdikian stated, "Every edition has been considered by some to be alarmist and every edition ends up being too conservative."[62] In this latest version, Bagdikian wrote that the number of corporations controlling most of the media decreased to five: Disney, News Corporation, Time Warner, Viacom, and Bertelsmann.[63] He argued, "This gives each of the five corporations and their leaders more communications power than was exercised by any despot or dictatorship in history."[8]

The book became a "standard text for many college classes"[64] and, along with Manufacturing Consent by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, in the opinion of Neil Henry, is a work that is the "most widely cited scholarly work about the effects of economics on modern news media practices, including market and political pressures that determine news content."[65] The book was criticized by Jack Shafer for alleged bias.[66] The Christian Science Monitor, though accepting such problems, declared that it is a "groundbreaking work that charts a historic shift in the orientation of the majority of America's communications media—further away from the needs of the individual and closer to those of big business."[67]

Political views

[edit]Bagdikian was a self-proclaimed advocate for social justice.[4] He described the McCarthy era as "very reactionary."[31] In 1997 Bagdikian opined that "criticizing capitalism has never been a popular subject in the general news."[68] In the 2000 U.S. presidential election Bagdikian endorsed Ralph Nader, the Green Party candidate. He was a founding member of the grassroots network Armenians for Nader. He stated: "I think Ralph Nader has already powerfully defined the issues in this campaign and has had influence on the positions of both major party candidates."[69] He argued that "there's a natural hostility among corporate organizations toward Nader, because they see him as the person who's embarrassed them endlessly and sees them as part of the national political problem."[70]

He appeared on KPFK along with Serj Tankian and Peter Balakian on April 24, 2005, to talk about the Armenian Genocide.[71]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had a 200-page file on Bagdikian spanning from 1951 to 1971. One document described him as well known in FBI files as a "writer who has criticized the FBI in the past. He has made snide remarks relative to" FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and "some of his work has been described [specifically, by Hoover] as 'utter bunk'."[72] When Bagdikian requested all his FBI record under the Freedom of Information Act in 1975, the FBI withheld records on the part he played in the Pentagon Papers case. They were not released until 2018.[73]

Legacy and recognition

[edit]C. Edwin Baker describes Bagdikian as "probably the most quoted, certainly one of the most acute, commentators on media ownership."[74] Arthur S. Hayes, Fordham University professor, wrote in his 2008 book Press Critics Are the Fifth Estate that Bagdikian has been "farsighted, inspirational, influential, long lasting, and a forerunner."[75][5] Sociologist Alfred McClung Lee praised Bagdikian as having the virtues of both an investigative journalist and a participant-observing social scientist.[76] Robert D. McFadden of The New York Times called Bagdikian "a celebrated voice of conscience for his profession, calling for tougher standards of integrity and public service in an era of changing tastes and technology."[8] Edward Wasserman, the dean of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism at the time of his death, Bagdikian was a "major figure in 20th century US journalism and journalism education, and we're all his beneficiaries."[77][28] Jeff Cohen, the founder of the media watch group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) stated:

From Day One, no journalist more influenced FAIR's standard media critique than Ben Bagdikian. The first edition of his Media Monopoly was our bible.[78]

Michael Moore has named The Media Monopoly the most influential book he ever read.[79] Robert W. McChesney, who cites Bagdikian as one of the strongest influences on him, called Bagdikian one of the finest journalists of the 20th century.[80] McChesney argued that Bagdikian was "certainly accorded more respect by working journalists" than Herman and Chomsky, the authors of Manufacturing Consent, due to their perceived radicalism, in contrast to Bagdikian's liberal views.[81] Progressive journalist and writer John Nichols, writing for The Nation, called Bagdikian a "pioneering media reformer."[51] In an interview with Democracy Now!, he said of Bagdikian :

He was our great inspiration. [...] If you were to ask Noam Chomsky and so many other folks who have really identified the challenges of media today, they all go back to Bagdikian, this incredible journalist, an Armenian-American immigrant who became the best in his field and then stepped out of his field, became a critic and a commentator, and essentially said, "Look, this monopolization is going to put so much power in a handful of corporate elites that we will begin to lose journalism." Clearly, that has happened.[82]

The Pentagon Papers controversy at The Washington Post was recounted in the Steven Spielberg film The Post (2017), where Bagdikian was played by Bob Odenkirk.[83]

Awards and honors

[edit]- Peabody Award (1950)[84]

- Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting, Edition Time (staff contributor; 1953)[85]

- Hillman Prize (1956) for his series on civil liberties[86]

- Guggenheim Fellowship (1961)[34]

- James Madison Award (1998)[14][27]

Bagdikian received honorary degrees, among others, from[27] Brown University (Doctor of Humane Letters, 1961),[87] Clark University (Doctor of Letters, 1963),[20] Berkeley Citation from University of California, Berkeley (equivalent of an honorary degree, 1990),[88][28] University of Rhode Island (Doctor of Letters, 1992).[89] He was the commencement speaker of the 1972 Journalism Convocation of Northwestern University.[90]

The fellowship program of the progressive magazine Mother Jones is named for Bagdikian due to his "professional record, his personal integrity, and his commitment to social justice."[91]

Bagdikian was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame on October 30, 2016. According to the board he had "long and significant ties to Rhode Island."[92]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Our Boys Committee (1951). Armenian-American Veterans of World War II. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 173.

- ^ Taft, William H. (2016). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Journalists. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 9781317403258.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (21 February 1989). "Variety's New Look for New Readers". The New York Times.

Ben Bagdikian, the media commentator...

- ^ a b Rubens 2011, p. ix.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Schudel, Matt (11 March 2016). "Ben H. Bagdikian, journalist with key role in Pentagon Papers case, dies at 96". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e T. W. Pietsch III. "Baghdikian Family Genealogy" (PDF). washington.edu. University of Washington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Rubens 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w McFadden, Robert D. (11 March 2016). "Ben H. Bagdikian, Reporter of Broad Range and Conscience, Dies at 96". The New York Times.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Vetter, Herbert F., ed. (2007). Notable American Unitarians 1936-1961. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Square Library. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-6151-4784-0. archived text

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 10.

- ^ DiCanio 2002, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bryant, Dorothy (1 June 2004). "Bagdikian's Long Journey to Journalistic Heights". Berkeley Daily Planet. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 8.

- ^ DiCanio 2002, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Mace, Emily. "Bagdikian, Ben H. (1920-2016) | Harvard Square Library". Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ a b Rubens 2011, p. 19.

- ^ a b Rubens 2011, p. 187.

- ^ a b Keogh, Jim (16 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian '41 championed the public's right to know". clarku.edu. Clark University. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)() - ^ Rubens 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 32.

- ^ "Marlene Bagdikian, 1928 - 2022". www.legacy.com. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ^ "Ben H. Bagdikian dies at 96; journalist who helped publish the Pentagon Papers". Los Angeles Times. 11 March 2016.

- ^ "Memorial service to be held July 2 for Ben Bagdikian". journalism.berkeley.edu. UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. 23 June 2016. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Sleeman, Elizabeth, ed. (2003). "Bagdikian, Ben Haig". International Who's Who of Authors and Writers 2004 (19th ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 28. ISBN 9781857431797.

- ^ a b c d Nolte, Carl (11 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian, noted media critic, dies at 96". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017.

- ^ Rubens 2011, p. 37.

- ^ a b Jablon, Robert (12 March 2016). "Media commentator Ben Bagdikian dies at 96; shared Pulitzer at Providence Journal". The Providence Journal.

- ^ a b Rubens 2011, p. 43.

- ^ "Ben Bagdikian, journalist who helped publish the Pentagon Papers, dies". The Guardian. via Associated Press. 12 March 2016.

- ^ DiCanio 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b "Ben H. Bagdikian". gf.org. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021.

- ^ Parker, Edwin B. (Autumn 1971). "Reviewed Work: The Information Machines: Their Impact on Men and the Media. by Ben H. Bagdikian". Public Opinion Quarterly. 35 (3): 504–505. doi:10.1086/267937. JSTOR 2747948.

- ^ Ellsberg, Daniel (2002). "Chapter 29: Going Underground". Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03030-9.

- ^ Leahy, Michael (September 9, 2007). "Last". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Warren R. Ross (September–October 2001). "A courageous press confronts a deceptive government". UU World. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "How the Pentagon Papers Came to be Published by the Beacon Press: A Remarkable Story Told by Whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, Dem Presidential Candidate Mike Gravel and Unitarian Leader Robert West". Democracy Now!. July 2, 2007. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ Witcover 1971, p. 11.

- ^ Flink, Stanley E. (1997). Sentinel Under Siege: The Triumphs and Troubles of America's Free Press. Westview Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780813333441.

- ^ Graham, Katharine (2012). "Personal History". In King, Elliot; Chapman, Jane L. (eds.). Key Readings in Journalism. Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 9781135767679.

- ^ Ungar, Sanford J. (1972). The Papers and the Papers. New York: E. P. Dutton. p. 144. ISBN 9780525174554.

- ^ Hayes 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Witcover 1971, p. 12.

- ^ ""The Shame of the Prisons"- Ben Bagdikian - Washington Post". New York University. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

- ^ Bagdikian, Ben H. (1976). Caged: Eight Prisoners and Their Keepers. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060101749.

- ^ Nemeth, Neil (2003). "The News Ombudsman at the Washington Post". News Ombudsmen in North America: Assessing an Experiment in Social Responsibility. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 50, 60. ISBN 9780313321368.

- ^ Pao, Roann (14 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian, reporter and former campus Graduate School of Journalism dean, dies at 96". The Daily Californian. University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Silverblatt, Art; Enright Eliceiri, Ellen M. (1997). Dictionary of Media Literacy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 19. ISBN 9780313297434.

- ^ a b c Nichols, John (14 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian Knew That Journalism Must Serve the People—Not the Powerful". The Nation. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Smoke in the Eye: Interview with Ben Bagdikian". Frontline. PBS. 1996. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Telecommunications Professor John Galbraith and Professor Ben Bagdikian testified on the effects of profit on news reporting". c-span.org. C-SPAN. 28 April 1987.

- ^ "Corporations Threaten TV, Witnesses Say". The New York Times. 29 April 1987.

- ^ Ellis, Justin (7 August 2013). "Summer Reading 2013: "The Information Machines: Their Impact on Men and the Media" by Ben H. Bagdikian (1971)". niemanlab.org. Nieman Journalism Lab.

- ^ Lochner, Tom (11 March 2016). "Former UC Berkeley journalism Dean Ben Bagdikian dies at 96". Times-Standard. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

- ^ Collins, Ronald K. L.; Chaltain, Sam (2011). We Must Not Be Afraid to Be Free: Stories of Free Expression in America. Oxford University Press. p. 337. ISBN 9780195175721.

He is the author of the widely acclaimed book The Media Monopoly.

- ^ McDowell, Edwin (9 April 1983). "Censhorship raised in book dispute". The New York Times.

- ^ "An independent Boston publisher said Wednesday it would not..." United Press International. 7 April 1983.

- ^ Hacker, Andrew (26 June 1983). "Our Ministry of Information". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ben Bagdikian, The Media Monopoly (Beacon Press, 1983)". journalism.nyu.edu. New York University. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017.

- ^ Zuckerman, Laurence (13 January 2000). "Questions Abound as Media Influence Grows for a Handful". The New York Times.

- ^ Mirrlees, Tanner (2013). Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 9781136334658.

- ^ Streshinsky, Maria (15 March 2016). "Is Basic Social Justice Really a Matter of Personal Opinion?". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017.

- ^ Henry, Neil (2007). American Carnival: Journalism Under Siege in an Age of New Media. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780520931541.

- ^ Shafer, Jack (4 August 2004). "The Media Monotony". Slate.

- ^ Manuel, Bruce (10 August 1983). "Dangers of media concentration". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Wines, Michael (13 April 1997). "Looking for Something to Say About Nothing". The New York Times.

- ^ ""Armenians for Nader" Committeee [sic]Formed". Asbarez. 1 September 2000.

- ^ Welch, Matt (3 November 2000). "Ralphing on the Media". Online Journalism Review.

- ^ "KPFK 90.7 to Air Program on Armenian Genocide". Asbarez. 22 April 2005. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Leopold, Jason (7 September 2017). "Government officials have long watched journalists who pissed them off". Vice News.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Seth (29 August 2018). "The FBI's secret investigation of Ben Bagdikian and the Pentagon Papers". Columbia Journalism Review.

- ^ Baker, C. Edwin (2006). Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781139461030.

- ^ Hayes 2008, p. 54.

- ^ McClung Lee, Alfred (March 1984). "Reviewed Work: The Media Monopoly by Ben H. Bagdikian". Contemporary Sociology. 13 (2). American Sociological Association: 173–174. JSTOR 2068881.

- ^ Kennedy, Mark (13 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian, 96; helped publish Pentagon Papers". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Cohen, Jeff (12 March 2016). "Ben Bagdikian, Visionary". Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017.

- ^ Moore, Michael (October 8, 2014). "The Media Monopoly by Ben Bagdikian RT @DavidfCoyle : @MMFlint what is the most influential book you have ever read?#RogerMe25". Twitter. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ McChesney 2008, p. 23.

- ^ McChesney 2008, p. 517.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (16 March 2016). "Remembering Journalist & Media Critic Ben Bagdikian, Author of "The Media Monopoly"". Democracy Now!.

- ^ Ciampaglia, Dante A. (22 December 2017). "'Better Call Saul' Star Bob Odenkirk Talks Playing 'Washington Post Reporter Ben Bagdikian in 'The Post'". Newsweek.

- ^ "Providence Journal, Its Editor and Publisher, Sevellon Brown, and Ben Bagdikian, Reporter for the Series of Articles Analyzing the Broadcasts of Top Commentators". peabodyawards.com. 1950. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Editorial Staff of Providence (RI) Journal and Evening Bulletin". pulitzer.org. The Pulitzer Prizes.

- ^ "The Hillman Prize Previous Honorees". hillmanfoundation.org.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees: 1900s". brown.edu.

- ^ "Berkeley Citation – Past Recipients". berkeley.edu.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients". uri.edu.

- ^ "Northwestern University Commencement Speakers, 1892-2016" (PDF). northwestern.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2017.

- ^ "About Ben Bagdikian". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017.

- ^ "Newsman Ben Bagdikian among 14 inducted into RI Heritage Hall of Fame". The Providence Journal. 30 October 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- McChesney, Robert W. (2008). The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas. New York University Press. ISBN 9781583671610.

- DiCanio, Margaret (2002). "Ben Bagdikian". Memory Fragments from the Armenian Genocide: A Mosaic of a Shared Heritage. New York: Mystery and Suspense Press. pp. 66–73. ISBN 0-595-23865-3.

- Witcover, Jules (September 1971). "Two weeks that shook the press". Columbia Journalism Review. 10 (3): 7–15.

- Hayes, Arthur S. (2008). Press Critics are the Fifth Estate: Media Watchdogs in America. Praeger. ISBN 9780275999100.

- Rubens, Lisa (2011). "Ben H. Bagdikian" (PDF). Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019.

External links

[edit]- American media critics

- American journalism academics

- University of California, Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism faculty

- 20th-century American newspaper editors

- American newspaper reporters and correspondents

- American investigative journalists

- American political writers

- The Washington Post people

- The Providence Journal people

- American people of Armenian descent

- 20th-century American memoirists

- American male non-fiction writers

- Peabody Award winners

- Clark University alumni

- American Unitarian Universalists

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- Emigrants from the Ottoman Empire to the United States

- Armenians from the Ottoman Empire

- 1920 births

- 2016 deaths