Beauty and the Beast (Disney song)

| "Beauty and the Beast" | |

|---|---|

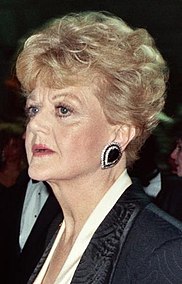

| Song by Angela Lansbury | |

| from the album Beauty and the Beast: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

| Released | October 29, 1991 |

| Genre | Show tune |

| Length | 2:44 |

| Label | Walt Disney |

| Composer(s) | Alan Menken |

| Lyricist(s) | Howard Ashman |

| Producer(s) |

|

"Beauty and the Beast" is a song written by lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken for the Disney animated feature film Beauty and the Beast (1991). The film's theme song, the Broadway-inspired ballad was first recorded by British-American actress Angela Lansbury in her role as the voice of the character Mrs. Potts, and essentially describes the relationship between its two main characters Belle and the Beast, specifically how the couple has learned to accept their differences and in turn change each other for the better. Additionally, the song's lyrics imply that the feeling of love is as timeless and ageless as a "tale as old as time". Lansbury's rendition is heard during the famous ballroom sequence between Belle and the Beast, while a shortened chorale version plays in the closing scenes of the film, and the song's motif features frequently in other pieces of Menken's film score. Lansbury was initially hesitant to record "Beauty and the Beast" because she felt that it was not suitable for her aging singing voice, but ultimately completed the song in one take.

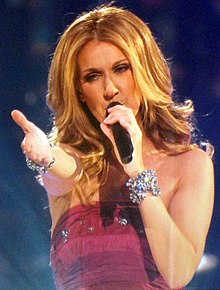

"Beauty and the Beast" was subsequently recorded as a pop duet by Canadian singer Celine Dion and American singer Peabo Bryson, and released as the only single from the film's soundtrack on November 25, 1991. Disney first recruited solely Dion to record a radio-friendly version of it in order to promote the film. However, the studio was concerned that the then-newcomer would not attract a large enough audience in the United States on her own, so they hired the more prominent Bryson to be her duet partner. At first Dion was also hesitant to record "Beauty and the Beast" because she had just recently been fired from recording the theme song of the animated film An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991). First heard during the film's end credits, the single was produced by Walter Afanasieff who also arranged it with Robbie Buchanan, and included on Dion's self-titled album (1992) and Bryson's album, Through the Fire (1994). The single was accompanied by a music video. Directed by Dominic Orlando, it combined footage of the singers recording the song at The Power Station with excerpts from the film.

Both versions of "Beauty and the Beast" were very successful, garnering both a Golden Globe and Academy Award for Best Original Song, as well as Grammy Awards for Best Song Written for Visual Media and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals. The single was also nominated for the Grammy Award for Record of the Year and the Grammy Award for Song of the Year. Lansbury's performance has been universally lauded by both film and music critics. While the Dion-Bryson version received mixed reviews from critics who felt that it was not as good as Lansbury's original, the single became a commercial success, peaking at number nine on the Billboard Hot 100 and becoming the better-known of the two renditions. In addition to returning Disney songs to the pop charts after a thirty-year absence, the success of "Beauty and the Beast" also boosted Dion's career and established her as a bankable recording artist. After "Beauty and the Beast" became the first Disney song to undergo a complete pop transformation, several contemporary artists were inspired to release their own radio-friendly renditions of Disney songs throughout the decade. Considered to be among Disney's best and most popular songs, "Beauty and the Beast" has since been covered by numerous artists. In 2004, the American Film Institute ranked "Beauty and the Beast" at number 62 on their list of the greatest songs in American film history.

The song is also featured in the 2017 live-action adaptation; sung by Emma Thompson as Mrs. Potts during the film and also as a duet cover version by Ariana Grande and John Legend during the end credits.[1][2][3] Grande and Legend's version of the song is an homage to the cover performed by Dion and Bryson for the 1991 film.[4][5] The song was also performed by Shania Twain in the 2022 television special Beauty and the Beast: A 30th Celebration, and as a duet with H.E.R. and Josh Groban.[6][7]

Writing and recording

[edit]

"Beauty and the Beast" was written by lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken in 1990.[8] Intending for the song to be "the height of simplicity",[9] the songwriters drew much of its influence from Broadway music.[10] Due to Ashman's failing health, some of Beauty and the Beast's pre-production was relocated to a hotel in Fishkill, New York, near Ashman's residence.[11] Of the songs he wrote for Beauty and the Beast, Menken devoted the most time to the title song.[9] The track was first recorded by British-American actress Angela Lansbury, who voices the character Mrs. Potts, an enchanted teapot. The songwriters first introduced "Beauty and the Beast" to Lansbury as a demo recording, which was accompanied by a note asking her if she might possibly be interested in singing it.[12] Although a seasoned film and stage performer who had previously done her own singing for Disney in the musical film Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971),[13] Lansbury, who was more accustomed to performing uptempo songs,[14] was hesitant to record the ballad because of its unfamiliar rock style.[15] Although she liked the song,[16] Lansbury also worried that her aging singing voice was no longer strong enough to record "Beauty and the Beast",[17] and was especially concerned about having to sustain its longer notes.[18] Lansbury suggested that the songwriters ask someone else to sing "Beauty and the Beast",[19] but they insisted that she simply "sing the song the way [she] envisioned it".[15]

On October 6, 1990,[8] "Beauty and the Beast" was recorded in a studio in New York City accompanied by a live orchestra; the songwriters preferred to have all performers and musicians record together, as opposed to separating the singers from the instrumentalists.[20] On the day of her scheduled recording session, Lansbury's flight was delayed due to a bomb threat, which prompted an emergency landing in Las Vegas.[21] Unaware of her whereabouts for several hours, the filmmakers had begun making plans to reschedule the session until Lansbury finally telephoned the studio once she arrived safely in New York.[20] At the behest of one of the directors, Lansbury recorded a demo of the song for them to use in the event that no other actress was available to sing it on her behalf, or no character other than Mrs. Potts was deemed suitable.[13][22] Ultimately, Lansbury recorded her version in one take, which wound up being used in the final film.[22][23] Producer Don Hahn recalled that the actress simply "sang 'Beauty and the Beast' from beginning to end and just nailed it. We picked up a couple of lines here and there, but essentially that one take is what we used for the movie".[23] Lansbury's performance moved everyone who was present in the recording studio at the time to tears.[24] Lansbury credited recording the song with ultimately helping her gain further perspective on Mrs. Potts's role in the film.[25]

Some of Ashman's cut lyrics from the 1991 film were reinstated for the version in the 2017 film.[26]

Animation of the Beauty and the Beast and ballroom sequence

[edit]The scene in Beauty and the Beast during which the song is heard is the moment when Belle and the Beast's true feelings for each other are finally established.[27][28] Set in the ballroom of the Beast's castle, "Beauty and the Beast" is performed by the character Mrs. Potts, an enchanted teapot, midway through the film as she explains the feeling of love to her young teacup son Chip,[29] referring to the emotion as "a tale as old as time".[30] According to Armen Karaoghlanian of Interiors, "Belle familiarizes the Beast with the waltz and as soon he feels comfortable, he gracefully moves her across the floor".[27] Afterwards, the song continues to play instrumentally as Belle and the Beast retire to the balcony for a romantic candlelit dinner.[31] Believed to be the "centerpiece that brings Beauty and her Beast together,"[32] the sequence offers an insight into both characters' psyches. From the Beast's perspective, it is the moment he realizes that he wants to confess his true feelings for Belle to her[31] and "decides he wants to tell Belle he is in love with her".[33] Meanwhile, Belle begins to fall in love with her captor.[34] Writing for The Globe and Mail, Jennie Punter reviewed it as the scene in which "romance finally blossoms".[35] Film critic Ellison Estefan, writing for Estefan Films, believes that the sequence is responsible for "add[ing] another dimension to the characters as they continue to fall deeply in love with each other".[36] Explaining the song's role in the film, director Kirk Wise described the scene as "the culmination of their relationship,"[37] while producer Don Hahn pegged it as "the bonding moment of the film when the two main characters finally get together".[38]

The scene had long been envisioned as having a more live-action feel to it than the rest of the film, an idea that originated from story artists Brenda Chapman and Roger Allers, who were the first to suggest that the ballroom be built using computers.[40] As the film's executive producer, former Head of Disney's film division Jeffrey Katzenberg recalled that he began working on Beauty and the Beast deciding what its "wowie" moment would be, defining this as "the moment in the movie where you see what's on the screen and go, 'Wow-IEE'"; this ultimately became the film's ballroom sequence.[41] According to Hahn, the scene was conceived out of the filmmakers' desire to manipulate the camera in order to "sweep" the audience away.[42] Allers and Chapman conceived the ballroom in order to provide the characters with an area in which they could linger, and were surprised by the amount of artistic freedom with which they were provided by the animators, who agreed to adjust to the changes in perspective that would result from the moving camera.[42] While Allers decided to raise the camera in order to view the dancing couple from the overhead chandelier, Chapman decided to rotate the camera around Belle's skirt as the couple danced past it.[42]

In their dance together, Belle and the Beast move toward the camera, as we pan up and into the 3D chandelier. In the next shot, the camera slowly drops from the ceiling as we once again move alongside the 3D chandelier. This adds depth to the scene, as the chandelier is placed at the forefront of the image and Belle and the Beast are in the distance. This shot continues as we move down below and gracefully move around them. The Beast then sways Belle around and near the camera, once again providing us with an illusion that a camera is following these characters around in an actual ballroom. In a wide shot of Belle and the Beast dancing, the camera begins dollying back as Mrs. Potts and Chip appear in the frame. These beautiful compositions and camera movements show us how space functions within an animated feature film.

— Armen Karaoghlanian of Interiors

Regarded as an example of "a pronounced use of height and of vertical movement in sets and settings, in virtual camera movement ... and in the actions of characters" by Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History author Sheldon Hall,[43] Beauty and the Beast was one of the first feature-length animated films to use computer-generated imagery,[44][45][46] which is prominently exhibited throughout the film's "elaborate" ballroom sequence.[47] Light Science: Physics and the Visual Arts author Thomas D. Rossing believes that the filmmakers aimed to achieve "a moving perspective that would follow the dancers around the room, giving visual expression to the soaring emotions of the scene".[48] CGI supervisor Jim Hillin was hired by Hahn to oversee the design of the scene's graphics.[49] However, because the computer-animation medium was so unfamiliar to the filmmakers at the time,[45] at one point they had considered having Belle and the Beast simply dance in complete darkness – save for a single spotlight – should the project be unsuccessful;[27] they jokingly referred to this idea as the "Ice Capades" version.[50]

First rendered as a simple cube,[27] the filmmakers used computers to design the ballroom as a production set, making it the first full-dimensional computer-generated colored background in history.[27] Unlike Disney's previous CGI ventures, Beauty and the Beast's ballroom was a much more detailed task that required animators to work exclusively with computers to compose, animate and color the scene.[51][52] According to Hillin, the revolutionary use of computers allowed for a combination of theatrical lighting and "sweeping" perspectives, which ultimately introduced live-action techniques to animation.[38] To make the scene a "special moment" for the characters,[53] a "virtual camera" was used to allow the animators to create the illusion of tracking, panning and zooming[52] that "establish[es] the mood" while helping audiences experience what the characters themselves are experiencing.[38] Imitating tracking shots, the camera frequently soars and zooms around the couple.[54] The camera first follows Belle and the Beast as they enter the ballroom before panning until it finally returns to focus on the two characters.[55] In his book Basics Animation 02: Digital Animation, author Andrew Chong wrote that "The sweeping camera move with a constantly shifting perspective during the ballroom sequence was a composition of traditionally drawn elements for the characters with digitally animated scenery".[56] Several computer animators, layout artists, art directors and background artists used their combined efforts to achieve the scene's end results; the ballroom's official dimensions read 72 feet high, 184 feet long and 126 feet wide.[57] The space also houses 28 windows and a dome that measures 86 by 61 feet; the dome's mural was first hand-painted before it was texture-mapped onto it using a computer.[57] Each element was carefully constructed individually.[57] Timothy Wegner described the finished product in his book Image Lab as a "huge and elegant" ballroom in which "the walls are decorated with elaborate moldings, Corinthian columns, and hundreds of candles".[58]

Writing for Combustible Celluloid, Jeffrey M. Anderson believes that "The animators understood that the new technology couldn't be used to represent organic beings, so they simply used it for backgrounds; i.e. the swirling, spinning ballroom during the 'Beauty and the Beast' dance number".[59] At first, Belle and the Beast were vaguely represented by computer-animated box and egg-shaped "stand-ins" in order to choreograph their dance while the ballroom was still little more than a "chicken wire" frame.[40] Andrew Osmond, author of 100 Animated Feature Films, described this crude depiction of the characters as "wire frames moving in staccato".[60] The characters were eventually updated to "stiff, line-drawn" versions of themselves.[61] Because Belle and the Beast are so "interconnected" during this scene, both characters were animated solely by Belle's supervising animator James Baxter;[38] the Beast's supervising animator Glen Keane eventually traced over Baxter's work.[62] Baxter prepared himself for animating the scene by studying ballet dancers in addition to taking dance lessons himself.[38] Throughout the entire film, Belle moves with a ballerina's turnout;[63] the Los Angeles Times film critic Charles Solomon observed that Belle looks "liveliest and prettiest" during this scene.[64] At one point, both Baxter and Keane plotted out their characters' routine themselves under the guidance of a professional dance coach.[62] A software created by Pixar named CAPS (Computer Animation Production System) allowed the animators to paint Belle and the Beast using computers as opposed to the more conventional and time-consuming method of painting animated characters by hand.[56][65] Art director Brian McEntee suggested a blue and gold colour scheme for the characters' costumes at a late-night meeting because he felt that the colors were "compelling" and "regal".[66] Adhering to the ballroom's blue and gold color scheme, Belle's gold ballgown complements the trim on the Beast's tuxedo, as well as the color of the ballroom itself, while the Beast's royal blue attire complements his eyes, the night sky, the curtains and the floor tiles.[27] Meanwhile, Julia Alexander of Movie Mezzanine wrote that "The elegance of their costumes against the background of a golden hall and a star filled sky adds to the whimsical romanticism of the movie".[67] The entire sequence took several months to complete, much of which was spent syncing the traditionally animated couple with their computer-animated environment,[68] which otherwise would have been virtually impossible had the filmmakers decided to use a more traditional method.[56][69]

When Beauty and the Beast was released, many animators were impressed with the studio for "pushing the envelope", while some considered the scene to be "a miserable failure", accusing its new technology of distracting from "the moment".[70] Describing the scene as "an early experiment in computer animation," Josh Larsen of Larsen on Film observed that the ballroom sequence features "the camera swooping in and around to provide an expansive sense of space that 3-D still isn't able to capture".[71] In her book The Beautiful Ache, author Leigh McLeroy wrote that the scene represents "one of those strange moments where love creeps in against all odds and insists on staying put".[72] Audiences tend to remember the ballroom sequence as "the one in which Belle and the Beast share a romantic dance as the camera files and spins around them".[73] Angela Lansbury recalled being "astonished" when she first saw the "huge" and "unique" scene.[42] In Moviepilot's Chris Lucas' opinion, "The ballroom scene remains the one that truly symbolizes their adoration for each other".[74] IGN believes that the scene "signals the completion of [the Beast's] inner change - from irascible recluse into [Belle's] true love".[75]

Music and lyrical interpretation

[edit]The original film version of "Beauty and the Beast" performed by Lansbury was written in the key of D-flat major[76] at a "moderately slow" tempo of 84 beats per minute (Andante),[77] at a duration of two minutes and forty-six seconds.[78] An "eloquent"[79] rock-influenced[15] pop song with a "calm" and "lilting" melody,[80] Stephen Whitty of NJ.com described "Beauty and the Beast" as a "Broadway ballad".[81] Film critic Roger Ebert described the song's melody as "haunting",[82] while Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwarzbaum dubbed the song as a "lullaby".[32] The Disney Song Encyclopedia author Thomas S. Hischak described Menken's melody as "flowing",[83] while BuzzFeed's Aylin Zafar wrote that the song is "Tender and warm".[84] Writing for the Chicago Tribune, Gene Siskel described Lansbury's voice, which spans two octaves from F3 to B♭5,[77] as "richly textured".[85] Meanwhile, Michael Cheang of The Star and Bill Gibron of PopMatters wrote that Lansbury performed using a "fragile"[34] "calm, motherly" tone.[86] Instrumentally, "Beauty and the Beast" features several chord changes, woodwinds,[87] and violins.[88] GamesRadar observed that "Beauty and the Beast" includes a key change during which "the music swells, and then the orchestra subsides to leave just trembling violins".[88] Describing the ballad as "soaring", TV Guide compared "Beauty and the Beast" to "Shall We Dance?" from the musical The King and I.[89]

R.L. Shaffer of IGN identified "Beauty and the Beast" as a "tear-jerking poetic ballad".[90] Film Genre 2000: New Critical Essays author Wheeler W. Dixon believes that the song's lyrics are about the couple's "implicit promise of regeneration through love".[91] 29 lines in length,[92] all of which are exactly five syllables,[93] "Beauty and the Beast" is a love song about a couple's transformation from friends into "something more".[94][95] The film's theme song,[96] its lyrics "capture the essence of the film"[97] by describing the relationship between Beauty and the Beast's two main characters, specifically citing ways in which the two have changed each other for the better and finally learned to accept their differences and mistakes.[98] According to Jake Cole of Not Just Movies, the first stanza begins "in earnest, and the subtlety of it has the ironic effect of being overpowering".[92] Beginning with Lansbury singing the lyrics "Tale as old as time, true as it can be,"[77] JoBlo.com wrote that the song "offers a sure sign of romance between the Beauty and her Beast".[99] Meanwhile, Songfacts believes that "The message of the song is that a couple can be 'as old as time' no matter how different they are".[100] According to Chris Lucas of Moviepilot, Ashman's lyrics describe the couple's "hesitation and surprise at falling in love unexpectedly,"[74] while author Thomas S. Hischak wrote in The Disney Song Encyclopedia that the song is "about how two tentative hearts are united in love".[83] Featuring the line "Barely even friends, then somebody bends, unexpectedly,"[101] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune believes that the ballad "makes the case for all lovers to look past their partners' faults and into their hearts,"[85] while Cole wrote, "Ashman goes for the truth ... we don't know we're in love until we spend time with someone and unforced adjustments make the pieces fall into place".[92] The Emperor's Old Groove: Decolonizing Disney's Magic Kingdom author Brenda Ayres cited the song as an "[indicator] that a reciprocal power relationship has developed between Belle and the Beast ... confirm[ing] 'his transformation, her legitimacy, and their powerful unity".[102] According to the lyricist's website, "Beauty and the Beast" summarizes the way in which "Belle tames the beast and finds the happy ending she has dreamed about".[103] The Meanings of "Beauty and the Beast": A Handbook author Jerry Griswold believes that the song's opening line "tale as old as time" alludes to the fact that Belle's story is an ancient, timeless one "deliberately situated within the context of other traditional tales;" hers is simply "the newest incarnation" of it.[104] The Translation of the Songs in Disney's "Beauty and the Beast": an example of Manipulation author Lucía Loureiro Porto agrees that although the song "does not tell any story, it is made of phrases that imply that love is as old a feeling as mankind".[105] According to Perry Seibert of AllMovie, "Beauty and the Beast" is "as sappy as Ashman ever got as a lyricist". Seibert believes that the song "acknowledges its own banality ... without minimizing or mocking its inherently sweet description of true love".[106] Reflecting upon Ashman's death, Roger Moore of the Chicago Tribune believes that the song "was [Ashman's] farewell to love and life and imagination".[107]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]"Beauty and the Beast" received widespread acclaim from film and music critics alike.[108] Film critic Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised "Beauty and the Beast", describing it as "a glorious ballad" while dubbing it Ashman and Menken's "biggest triumph".[109] Beliefnet called the song "stirring",[110] while Hal Hinson of The Washington Post considers it to be among the film's best.[111] Roger Moore of the Chicago Tribune referred to "Beauty and the Beast" as a "brilliant" song that "can move you to tears,"[107] while James Berardinelli of ReelViews cited it among the film's most "memorable" songs.[54] Anthony Quinn of The Independent highlighted "Beauty and the Beast" as the film's best song, going on to praise Lansbury's "magnificent" performance,[112] while the Deseret News' Chris Hicks called it "beautiful".[113] Simon Brew of Den of Geek specifically enjoyed the lyrics "bittersweet and strange, finding you can change," describing the song as "superb".[114] Lansbury's vocal performance has also been singled out for praise: Slant Magazine's Jaime N. Christley wrote that Lansbury "delivers the film's title tune, gooey treacle that it is, like nobody's business".[115] Describing the song as "beautiful", the Chicago Tribune's Gene Siskel wrote that "Beauty and the Beast" is "performed poignantly by the richly textured voice of Angela Lansbury".[85] Similarly, PopMatters' Bill Gibron penned, "the moment Angela Lansbury's trite teapot steps up to sing the title song, all dry eye bets are off".[116] Aylin Zara of BuzzFeed opined that Lansbury's version is superior to the single, penning, "Though the commercial pop version of 'Beauty and the Beast,' sung by Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson, is great, the film version — performed by Angela Lansbury as Mrs. Potts — is even better. Tender and warm ... it tugs at all the right heartstrings to get your eyes a little misty".[84] Rachael Monaco of AXS cited "Tale as old as time. Tune as old as song. Bittersweet and strange. Finding you can change. Learning you were wrong. Certain as the sun rising in the East. Tale as old as time, song as old as rhyme, Beauty and the Beast" as the film's best lyric.[31] Entertainment Weekly's Darren Franich, however, admitted to preferring "Be Our Guest" and "Belle" over "Beauty and the Beast".[117]

By far the songwriters' biggest triumph is the title song, which becomes even more impressive in view of the not-very-promising assignment to create a 'Beauty and the Beast theme song. But the result is a glorious ballad, one that is performed in two versions, as both a top-40 style duet heard over the closing credits and a sweet, lilting solo sung by Ms. Lansbury during the film's most meltingly lovely scene. For the latter, which also shows off the film's dynamic use of computer-generated animation, the viewer would be well advised to bring a hanky.

The ballroom sequence during which Belle and the Beast dance to "Beauty and the Beast" continues to be praised, especially for its use of computer animation.[118][119] The first time the "Beauty and the Beast" musical sequence was made available to the public, it was in the form of an unfinished scene at the New York Film Festival in September 1991, to which Disney had been invited to premiere an incomplete version of Beauty and the Beast that largely consisted of uncolored pencil tests and storyboards.[120][121] The New York Times' Janet Maslin appreciated being previewed to the unfinished ballroom scene, writing, "when the radiant sight of Beauty and the Beast waltzing together, to the sound of the lilting theme song by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman stirs emotion even in this sketchy form, then both the power and the artifice of animation make themselves felt".[120] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly crowned the sequence the film's "centerpiece".[32] Writing for The Seattle Times, Candice Russel described it as an "irresistible highlight",[122] while The Globe and Mail's Jennie Punter called the scene "glorious".[35] David Parkinson of Radio Times identified the ballroom sequence as the scene in which the film's use of CGI is "seen to best advantage".[123] The Chicago Tribune's Dave Kehr praised both layout artist Lisa Keene and computer animator Jim Hillin's combined efforts on the scene, identifying it as the film's "most impressive setting".[28]

When Beauty and the Beast was re-released in 3D in 2012,[124] Annlee Ellingson of Paste appreciated the way in which the sequence was adapted, describing it as "positively vertiginous".[125] Mike Scott of The Times-Picayune hailed it as a "gorgeous" and "memorable" scene that "still stands out as one of the film's more dazzling",[126] while Joanna Berry of The National wrote that "the ballroom sequence now seems to sparkle even more".[127] Although Boxoffice's Todd Gilchrist's response towards the film's 3D conversion overall was mixed, the critic admitted that "the times when the animators use computer animation to render the backgrounds", including during "the dance sequence between Belle and Beast ... are effective, immersive and maybe even memorable".[128] Contrastingly, Chris Hicks of the Deseret News felt that "Today, the ballroom sequence no longer feels fresh and new after so many recent computer-animated 3-D efforts, but that doesn't diminish the power of its gorgeous design".[129] Although James Berardinelli of ReelViews had originally reviewed the sequence as "the best scene in the movie", he felt that the 3D conversion "diminishes the romance and emotion of the ballroom dance".[54]

To viewers at the time, the computer effects in this climactic sequence[130] were astonishing.[131] The Beauty and the Beast ballroom sequence "thematized marriage in the dance" by illustrating a "nuptial rehearsal" which contrasts the "now" (3D animation) with "then" (2D animation) in a "successful marriage of character and set". The Studios After the Studios explains: "This chronological fusion was itself classicised by Mrs Potts' song: she turns a moment of industrial novelty into balance".[132]

Awards and recognition

[edit]"Beauty and the Beast" has won several awards. The song garnered the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song at the 49th Golden Globe Awards in January 1992.[133] The following March, "Beauty and the Beast" won the Academy Award for Best Original Song at the 64th Academy Awards.[134] The award was for Ashman, who had died of AIDS on March 14, 1991,[135][136] eight months before the film's release.[137] Menken acknowledged Ashman in his acceptance speech, while thanking Lansbury, Dion, Bryson and Afanasieff for their contributions.[134] Ashman's domestic partner Bill Lauch accepted the award on his behalf.[134] The following year, "Beauty and the Beast" garnered two wins out of eight nominations at the 35th Grammy Awards,[138] one for Best Song Written Specifically for a Motion Picture or Television.[139] An instrumental version arranged and conducted by Richard S. Kaufman won the 1993 Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental Performance. This rendition was performed by the Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra for the album Symphonic Hollywood, under the record company Varèse Sarabande.[140] The James Galway instrumental movie version performed by The Galway Pops Orchestra and featured on the album Galway at the Movies[141] was nominated in 1994 for the Best Pop Instrumental Performance Grammy.[142]

The American Film Institute ranked "Beauty and the Beast" 62nd on the organization's list of the 100 greatest songs in film history.[143] "Beauty and the Beast" is one of only four songs from Disney animated films to have appeared on the list.[144] When BuzzFeed organized "The Definitive Ranking Of The 102 Best Animated Disney Songs" list, "Beauty and the Beast" was placed at number four,[84] while the same website ranked the ballad Disney's fifth greatest love song.[145] Similarly, "Beauty and the Beast" is the fourth greatest Disney song according to M.[101] "Beauty and the Beast" finished 14th on GamesRadar's "30 best Disney songs in history" ranking.[88] On the website's list of the "Top 25 Disney Songs", IGN ranked "Beauty and the Beast" 22nd.[19] While Broadway.com ranked the song the second greatest Academy Award-winning Disney song,[24] Spin placed "Beauty and the Beast" at number 30 on the magazine's ranking of "Every Oscar Winner for Best Original Song".[87] On her list of the "11 Highest-Charting Songs From Disney Movies", author Nicole James of Fuse wrote that the Dion-Bryson version "cracked the Top 10, going to No. 9 on the charts (but No. 1 in our hearts)".[146] The same website included the pop version on its "Top 20 Disney Songs by Pop Stars" list.[147]

IGN placed the scene at number 83 on its ranking of the 100 greatest moments in film history.[75] Total Film ranked the scene ninth on its list of the "50 Greatest Disney Movie Moments".[148] In Den of Geek's article "Top 12 most memorable dance scenes in films", the ballroom sequence was ranked fifth.[149] GamesRadar also included the scene on the website's "50 Greatest Movie Dance Sequences", with author Kim Sheehan lauding it as "more moving and romantic than most live-action dances".[150] Oh No They Didn't ranked the song 2nd in its The Top 25 Disney Songs of All Time article, writing of its "vintage feel...brimming with life and originality", the "surprising effectiveness" of Lansbury's performance, and the "captivating on-screen animation".[151] The song was listed 8th is Metro's article Ranked – the top 20 Disney songs ever, with writer Duncan Lindsay commenting "... this dance sequence with Angela Lansbury's gorgeous tones was one of Disney's most romantic. What a song".[152]

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[153] | Silver | 200,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[154] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson version

[edit]| "Beauty and the Beast" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson | ||||

| from the album Beauty and the Beast: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Celine Dion and Through the Fire | ||||

| B-side | "The Beast Lets Belle Go" (instrumental) | |||

| Released | November 25, 1991 | |||

| Recorded | 1991 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Pop | |||

| Length | 4:04 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Composer(s) | Alan Menken | |||

| Lyricist(s) | Howard Ashman | |||

| Producer(s) | Walter Afanasieff | |||

| Celine Dion singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Peabo Bryson singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Beauty and the Beast" on YouTube | ||||

Background and recording

[edit]Much to Disney's surprise, Beauty and the Beast received three separate Academy Award nominations for Best Original Song.[11] To avoid dividing Academy voters and prevent a draw, Disney decided to promote the film's title song ahead of its fellow nominees "Belle" and "Be Our Guest" by releasing "Beauty and the Beast" as a single,[11] similar to the way in which Universal Pictures released "Somewhere Out There" from the animated film An American Tail as a single in 1986.[156] Coincidentally, Ashman and Menken had written the song so that it could potentially experience success outside of the Beauty and the Beast film itself.[9] Although Lansbury's rendition is very much appreciated, it was considered to be unsuitable for a commercial release or radio airplay.[156] Thus, the studio decided to make "Beauty and the Beast" the first Disney song to be arranged into a pop version of itself for the film's end credits.[157] Menken referred to this experience as a "turning point" in his career because it was also the first time one of his own compositions had ever undergone such a transformation.[158] The song was produced by Walter Afanasieff and arranged by musician Robbie Buchanan.[159] Menken commended Afanasieff for successfully making the song his own.[158]

Actress and singer Paige O'Hara, who voices Belle, was among the first artists to express interest in recording the pop version of "Beauty and the Beast", but Disney dismissed her for being "too Broadway".[160] Unable to afford to hire a "big singer" at the time, Disney selected rising Canadian recording artist Celine Dion.[17] Because she was relatively unknown to American audiences at the time, the studio doubted that Dion would have much of an impact in the United States on her own and subsequently hired the more well-known American singer Peabo Bryson to perform the song alongside her as a duet.[17] Disney contacted Dion's manager René Angélil about having the singer record "Beauty and the Beast" while she was on tour in England.[161] A fan of Dion's music, Menken personally wrote the singer a letter of approval.[162]

Hailing from the French-Canadian province of Quebec, Dion had just begun to learn English.[117] At first Dion was reluctant to commit to the project due to having just recently been replaced from recording "Dreams to Dream", the theme song of the animated film An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), in favor of American singer Linda Ronstadt, who had previously experienced great success with her rendition of "Somewhere Out There".[163][164] Ronstadt, who was producer Steven Spielberg's first choice,[163] only agreed to record "Dreams to Dream" after hearing Dion's demo.[161] Devastated by her termination, Dion eventually agreed to record "Beauty and the Beast" after listening to and being moved by Lansbury's performance.[161] Meanwhile, Bryson became involved with the project via Walt Disney Records Senior Vice President Jay Landers, who was friends with Walt Disney Pictures President of Music Chris Montan at the time.[165] The song's instruments were recorded first at The Plant Recording Studios in California. The singers later quickly recorded their vocals at The Power Station in New York over the Labor Day long weekend,[156] while mixing was completed at The Record Plant in Los Angeles.[166] The song was released as the only single from the film's soundtrack,[167] on which the song appears alongside Lansbury's version,[78] on November 25, 1991, by Walt Disney Records, Sony Music's labels Columbia Records and Epic Records.[168]

Composition

[edit]The single is a pop ballad[84][168] that lasts a total of four minutes and three seconds.[169] It begins in the key of F major at a moderately slow tempo of 72 beats per minute,[170] before modulating to D major, then G major, and ending in E major. The orchestration of the "conservatively-rendered pop song",[74][171] as described by Filmtracks, includes an electric oboe, keyboard, synthesizer and acoustic guitar.[172] Additionally, the song's "jazzy" instrumentation heavily relies on drums, an instrument that is noticeably absent from the remainder of the soundtrack.[173] According to Molly Lambert of Grantland, the track is "a sweeping downtempo ... ballad" that evokes the "early '90s gossamer high-tech style",[174] while Molly Horan of Refinery29 described it as a slow jam.[175] According to the Chicago Tribune's Brad Webber, Dion and Bryson's vocals are "resonant and multiflavored".[176] The opening line "Tale as old as time" is preceded by Dion ad-libbing "Ooh".[170] Similarities have been drawn between the song and "Somewhere Out There" from the animated film An American Tail.[156]

Critical reception

[edit]Unlike Lansbury's version, the Dion-Bryson single has earned generally mixed reviews; critics generally voice their preferences for Lansbury's version than Dion and Bryson's.[177] Filmtracks.com wrote that Dion's performance "made many fans wish that she had been given it as a solo".[171] Arion Berger of Entertainment Weekly praised Dion's vocals, describing "Beauty and the Beast" as "a perfect showcase for what she's best at".[178] Describing the duet as "extremely effective", Sputnikmusic's Irving Tan lauded the single, writing, "As the entirety of the film's poignancy is hinged on the chemistry between Bryson and Dion, having the pair pull their assignment off beautifully is ultimately a fantastic conclusion to events".[179] Jeff Benjamin of Fuse described the song as "a fantastic duet".[147] However, the Chicago Tribune's Brad Webber panned the rendition as a "sickly sweet, by-the-book ... standard" that "belie[s] [Dion's] talent",[176] while The Star's Michael Cheang accused the single of being "over-wrought".[86] Critics have been vocal in their preference for Lansbury's rendition; while praising the film version, Spin's Andrew Unterberger dismissed the single as "unbearably cloying".[87] Similarly, Kristian Lin of Fort Worth Weekly panned the single while complimenting Lansbury's version, advising audience members to "Clear out of the theater before Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson butcher the title song over the end credits,"[180] while Consequence of Sound's Dan Caffrey felt that "It's a shame that the most globally known version of 'Beauty and the Beast' is the one sung by Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson as opposed to the one sung by" Lansbury.[181]

Industry awards

[edit]At the 35th Grammy Awards, "Beauty and the Beast" won the award for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group With Vocals.[139][182][183] Additionally, the song was nominated for Record of the Year[138][184] and Song of the Year,[138][184] but lost both to Eric Clapton's "Tears in Heaven".[185] In Canada, "Beauty and the Beast" won a Juno Award for Single of the Year, beating Dion's own "If You Asked Me To".[186] In 1993, "Beauty and the Beast" also won an ASCAP Film and Television Music Award and ASCAP Pop Award for most performed song in the United States.[187][188] Awarding the Dion-Bryson version an 'A' grade, Grantland ranked the song second in its article "Counting Down the Top 10 in ... KIDS MUSIC!",[174] while Refinery29 ranked it the fifth greatest cover of a Disney song.[175] AXS included "Beauty and the Beast" among Dion's "Top five song lyrics or verses".[189]

Commercial performance

[edit]"Beauty and the Beast" was a commercial success all around the world. Billboard ranked it as the 5th biggest hit from animated Disney movies on Hot 100 history.[190] The song peaked at No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Dion's second top-ten hit on the chart after "Where Does My Heart Beat Now". The song peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot Adult Contemporary chart. In Canada, "Beauty and the Beast" peaked at number two.[191] Outside of North America, the song peaked within the top ten in New Zealand and the United Kingdom, while peaking within the top twenty in Australia, Netherlands and Ireland. The song sold over a million copies worldwide.[192]

Music video

[edit]Dion and Bryson's recording session at The Power Station[166] was filmed and later interpolated with various scenes from the film in order to create a music video,[156] was directed by Dominic Orlando.[193] The video premiered on the music channel VH-1, thus airing to an audience who was not accustomed to seeing animated characters appear in the midst of their regular programming.[156] The music video was made available for the first time on October 8, 2002, on the two-disc Platinum Edition DVD of the 1991 Disney animated feature film of the same name. Some years later the music video was made available again on the Diamond Edition of the various edition of the 1991 Disney animated feature film of the same name available from November 23, 2010. At the end the most recent edition that made available this music video was The Signature Collection edition that celebrate the 25th anniversary of the 1991 Disney animated feature film of the same name available since February 28, 2017.

Live performances

[edit]At the 1992 Oscars, Angela Lansbury, Celine Dion, and Peabo Bryson sang a composite of both versions from the film, backed by dancers dressed as Belle and the Beast.[194] Celine and Peabo also duetted at the Grammys,[195] World Music Awards,[196] AMA's,[197] Wogan,[198] The Tonight Show,[199] and Top of the Pops[200] later that year. The duo reunited in 1996 to perform the song for the television special Oprah in Disneyland,[201] while Lansbury provided an encore performance at the 25th Anniversary screening of the film.[202] Each of the 3 respective artists have performed the song in concerts later in their careers, outside the context of Disney's Beauty and the Beast. For example, Lansbury sang it at the 2002 Christmas concert with Mormon Tabernacle Choir.[203] Similarly, Dion and Bryson duetted at the JT Super Producers 94 tribute concert to David Foster,[204] and as part of Dion's 1994-95 The Colour of My Love Tour,[205] though they have also often sung with different duet partners. Dion has sung with Tommy Körberg,[206] Brian McKnight,[207] Terry Bradford,[208] Maurice Davis,[209] Barnev Valsaint,[210] and René Froger[211] among others; Peabo has sung with Coko[212] and Regine Velasquez.[213]

Personnel

[edit]- Celine Dion, Peabo Bryson - vocals

- Walter Afanasieff - synthesized bass, keyboards, synthesizer, drum programming, percussion

- Joel Peskin - oboe

- Ren Klyce: Akai AX73 and Synclavier programming

- Dan Shea: MacIntosh programming

Track listing

[edit]- 7-inch, 12-inch, cassette, CD and mini CD singles

- "Beauty and the Beast" – 3:57

- "The Beast Lets Belle Go" (instrumental) – 2:19

- Canadian CD maxi single

- "Beauty and the Beast" – 3:57

- "The Beast Lets Belle Go" (instrumental) – 2:19

- "Des mots qui sonnent" – 3:56

- "Délivre-moi" (live) – 4:19

- US promotional CD single

- "Beauty and the Beast" (radio edit) – 3:30

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Japan (RIAJ)[235] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[236] | Gold | 15,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[237] | Silver | 200,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[239] | Gold | 784,000[238] |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history

[edit]| Region | Date | Format(s) | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | January 7, 1992 |

|

Epic | [citation needed] |

| Japan | April 8, 1992 | Mini CD | SMEJ | [222] |

| United Kingdom | May 4, 1992 |

|

Epic | [240] |

Ariana Grande and John Legend version

[edit]| "Beauty and the Beast" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Ariana Grande and John Legend | ||||

| from the album Beauty and the Beast | ||||

| Released | February 2, 2017 | |||

| Length | 3:47 | |||

| Label | Walt Disney | |||

| Composer(s) | Alan Menken | |||

| Lyricist(s) | Tim Rice | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Ariana Grande singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| John Legend singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Beauty and the Beast" on YouTube | ||||

American singers Ariana Grande and John Legend covered "Beauty and the Beast" for the 2017 live-action adaption of the same name.[2][3] The accompanying music video, directed by Dave Meyers, premiered on Freeform on March 5, 2017.[241]

Charts

[edit]| Chart (2017) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[242] | 64 |

| Belgium (Ultratip Bubbling Under Flanders)[243] | 41 |

| Canada (Canadian Hot 100)[244] | 70 |

| France (SNEP)[245] | 71 |

| Hong Kong (Metro Radio)[246] | 1 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[247] | 99 |

| Japan (Japan Hot 100)[248] | 10 |

| Japan Hot Overseas (Billboard)[249] | 2 |

| New Zealand Heatseekers (RMNZ)[250] | 6 |

| Panama (Monitor Latino)[251] | 15 |

| Portugal (AFP)[252] | 84 |

| Scotland (OCC)[253] | 16 |

| South Korea (Gaon)[254] | 25 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[255] | 52 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[256] | 87 |

| US Kid Digital Songs (Billboard)[257] | 1 |

| US Adult Contemporary (Billboard)[258] | 20 |

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[259] | Platinum | 70,000‡ |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[260] | 2× Platinum | 120,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[261] Digital single |

Gold | 100,000* |

| Japan (RIAJ)[262] Streaming |

Gold | 50,000,000† |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[263] | Silver | 200,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[264] | Platinum | 1,000,000‡ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Covers and use in media

[edit]In 1993, jazz singer Chris Connor covered "Beauty and the Beast" for her album My Funny Valentine.[265] In 1998, O'Hara recorded a version of "Beauty and the Beast" for her album Dream with Me.[266] This marked the first time O'Hara had ever recorded the song,[267] although she has covered it live several times.[268] Billboard reviewed O'Hara's performance positively, writing that the actress provides each song with "the right youthful and gentle touch".[269] In 2000, singer Kenny Loggins covered the song on his children's music album More Songs from Pooh Corner.[270] In 2002, music group Jump5 covered "Beauty and the Beast" for the Walt Disney Records compilation album Disneymania;[271] a music video was released later that year and included as a bonus feature on the film's Platinum Edition DVD re-release, Beauty and the Beast: Special Edition.[272] Belonging to a segment known as "Chip's Fun and Games - For the Young at Heart", the music video features the group performing their "bouncy"[273] teen pop rendition of the song interpolated with scenes from the film.[274] Lauren Duca of The Huffington Post described the group's uptempo cover as "ridiculously '90s pop".[275] Meanwhile, musical duo H & Claire covered the song for the film's Platinum Edition re-release in the United Kingdom, which Betty Clarke of The Guardian dismissed as a "boring" rendition.[276]

On the country-themed compilation album The Best of Country Sing the Best of Disney (1996), "Beauty and the Beast" was covered by country band Diamond Rio.[277] To support the film's Diamond Edition re-release in 2010, singer Jordin Sparks recorded an R&B version of "Beauty and the Beast",[278] which was released on iTunes in September.[279] A music video directed by Philip Andelman was included on the re-release as a bonus feature,[280] part of the disc's "Music and More" segment.[281] The video depicts Sparks performing "Beauty and the Beast" in a castle.[278] In 2011, Sparks performed her rendition of the song live at the 30th anniversary of the televised Independence Day concert "A Capitol Fourth".[282] The cover is believed to have initiated the singer's gradual transition from music to film.[283] The compilation album Eurobeat Disney (2010) features a Eurobeat cover by singer Domino.[284] In 2014, actors Clare Bowen and Sam Palladio covered "Beauty and the Beast" for the television special Backstage with Disney on Broadway: Celebrating 20 Years, which documents the development of eight of Disney's Broadway musicals.[285] Both known for their roles in the television musical drama Nashville,[286] Bowen, a fan of the film, arranged the cover herself to satisfy the documentary producers' vision, who "were looking for performers who could offer unexpected interpretations of the [musicals'] familiar tunes".[287] Hilary Lewis of The Hollywood Reporter observed that Bowen and Palladio's rendition "is more stripped down" than the stage, Lansbury and Dion-Bryson versions.[285] The song has been covered multiple times as part of the We Love Disney album series. We Love Disney France (2013) features a cover by singers Garou and Camille Lou while We Love Disney Australia (2014) features a cover by operatic pop vocal group Sol3 Mio (2014).[288] We Love Disney Indonesia (2015) featured a cover by Chilla Kiana, while We Love Disney (Latino) (2016) featured a cover by Jencarlos and Paula Rojo.[289]

The song appears in the Broadway musical adaptation of the film, which premiered in 1994.[290] When the song first premiered on Broadway, there were few Broadway musicals at the time that featured ballads about love.[291] Originally covered live by actress Beth Fowler as Mrs. Potts,[292] "Beauty and the Beast" was included on the Original Broadway Cast Recording of the musical, again performed by Fowler.[293][294] While critical reception towards the musical ranged from negative to mixed, John Simon of New York commended Fowler for "manag[ing] to heat up and brighten [her] material".[295] Within the realm of reality television talent competitions, "Beauty and the Beast" was covered on The Voice Australia by contestants Lionel Cole and Sabrina Batshon in 2014.[296] Candice Barnes of The Sydney Morning Herald reviewed that the "song suited Sabrina best" while it was "too high" for Cole, in the end accusing both contestants of "destroying one of the best loved Disney songs with their vocal gymnastics".[297] In 1998, a version of the song, called "Beauty and the Bees", was made for the 3D movie It's Tough to Be a Bug!'s queue at Disney's Animal Kingdom and Disney California Adventure Park. The song, written by Bruce Broughton and George Wilkins, was released on the album The Legacy Collection: Disneyland. In 2021, the song was featured in the second season of High School Musical: The Musical: The Series.[298]

Impact and legacy

[edit]The overall success of Beauty and the Beast is partially attributed to the song's popularity.[299] Andrew Unterberger of Spin believes that the song "set the template for the quivering love theme in '90s Disney movies".[87] "Beauty and the Beast" was the first Disney song to undergo a complete pop rearrangement for commercial purposes.[157] After the success of Disney's The Little Mermaid revived the Disney musical in 1989,[300] Gary Trust of Billboard determined that "Once Beauty and the Beast followed in 1991 ... Disney was dominating charts like never before".[301] The single ended a thirty-year-long absence of Disney-released chart hits between the 1960s and 1990s, and inspired several similar hits; popular recording artists such as Elton John, Vanessa Williams, Michael Bolton, Christina Aguilera, Sting, Randy Newman and Phil Collins each experienced varying degrees of success with their own pop renditions of Disney songs throughout the decade.[301] When a then-unknown Aguilera was selected to record a pop version of "Reflection" from Disney's Mulan in 1998, she felt honored "to be in such wonderful company as" Dion.[302] Writing for Sputnikmusic, Irving Tan wrote that "Although the number's 1992 Academy Award for Best Original Song is something of an old chestnut at this point, it still bears some worth repeating - mainly as it is very likely the most famous of all the feature theme songs ever commissioned by Walt Disney Studios".[179]

Bill Gibron of PopMatters believes that the song "proved that the pen and ink designs that drove the company for nearly 80 years could transcend the genre and turn into something seminal ... something special ... something sensational".[34] The ballroom sequence continues to be held in high regard as one of Disney's crowning achievements.[303] Famous for successfully combining volumetric depth with dancing animated characters,[304] the scene is now revered by film critics as a classic, groundbreaking and iconic moment in animation history,[305][306][307] responsible for "chang[ing] the game" of contemporary animation.[308] Gaye Birch of Den of Geek pegged the scene as a Disney landmark because its accomplishments were "visually impressive in a way we hadn't experienced in a Disney movie before".[149] Huw Evans of Bournemouth University hailed the scene as "quite possibly the best piece of animation done on any feature film".[309] On the sequence's pioneering[75] use of computer-generated imagery, Annie Ellingson of Paste wrote that the ballroom was "innovative at the time for compositing hand-drawn characters on a computer-generated backdrop to enable dramatic sweeping camera moves".[125] Similarly, Empire's Helen O'Hara believes that the scene "paved the way for the new digital style of animation".[310] Mike Scott of The Times-Picayune holds the scene responsible for the subsequent success of Pixar' computer-animated films, concluding that "the warm reaction to that single scene would serve as a major springboard for the computer-animation industry -- and a major blow to hand-drawn animation".[126] In his 1995 review of Toy Story, film critic Roger Ebert encouraged audiences to re-watch Beauty and the Beast's ballroom sequence to better understand the newer computer-animated film's technology.[311] According to Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation author Tom Vito, the scene "made many skeptics in Hollywood begin to look at CG seriously,"[68] inspiring formerly "hostile" studio executives to pursue the new art form.[312] Additionally, the scene is also appreciated as a dance sequence. The Houston Press' Adam Castaneda extolled it as "one of the finest dance sequences in the history of film".[313] The golden ballgown Belle wears in the scene is now revered as iconic,[314] with Vogue ranking it among the most famous dresses in history.[315]

Beauty and the Beast: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack continues to be best remembered for spawning the Dion-Bryson single,[316] which established itself as an instant classic.[167] The success of song is believed to have established Dion as a bankable recording artist.[317][318] Before agreeing to record "Beauty and the Beast", Dion had been fired from recording the theme song of An American Tail: Fievel Goes West in favor of the more well-known Linda Ronstadt. Although both singles were released around the same time, the success of Dion's song ultimately eclipsed Ronstadt's "Dreams to Dream".[161] Biography.com referred to "Beauty and the Beast" as Dion's "real breakthrough into pop music stardom".[319] According to Lifetime, the song "cemented her international success,"[320] while People wrote that the release of "Beauty and the Beast" is when the singer truly went "global".[321] In the wake of "Beauty and the Beast"'s success, young fans who had not yet learned Dion's name would simply refer to her as "Beauty and the Beast".[318] The commercial success of "Beauty and the Beast" ultimately earned Dion a $10 million recording contract with Sony Music International;[162] the song was then included on Dion's successful self-titled studio album,[322] serving as the record's "cornerstone".[323] American musician Prince was so moved by Dion's performance on "Beauty and the Beast" after hearing it on the radio that he personally wrote a song for her to include on the album.[162][324] According to Filmtracks.com, "Beauty and the Beast" offered "a glimpse at a forthcoming mega-movie song presence for Celine Dion".[171] Evidently, the singer has since recorded the theme songs of several blockbuster films,[325] including "When I Fall in Love" from Sleepless in Seattle (1993), "Because You Loved Me" from Up Close & Personal (1996) and finally her signature song "My Heart Will Go On" from Titanic (1997).[326] "Beauty and the Beast" has since appeared on several of Dion's greatest hits albums,[327][328] while the singer has returned to Disney as a special guest to host various segments for certain Beauty and the Beast re-releases.[329]

In addition to establishing Bryson as a mainstream recording artist,[330] the singer has since returned to Disney on two separate occasions to record pop versions of "A Whole New World" and "As Long as There's Christmas", the theme songs of the animated films Aladdin (1992) and Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas (1997), respectively, both of which are duets.[331] Although "A Whole New World" was very successful, "Beauty and the Beast" remains a larger hit for the singer.[332] Bryson also included "Beauty and the Beast" on some of his compilation albums, including Through the Fire (1994) and Super Hits (2000).[333][334] Meanwhile, Afanasieff would go on to produce several Disney singles, including "A Whole New World" from Aladdin, for which he reunited with Bryson, and "Go the Distance" from Hercules (1997).[335] In 2004, Bryson was forced by the International Revenue Service (IRS) to auction off several of his personal belongings in order to help repay the singer's $1.2 million tax debt, among them his Grammy Awards for "Beauty and the Beast" and "A Whole New World".[336] While the latter song's Grammy was purchased by a friend and gifted back to the singer, Bryson's Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals trophy for "Beauty and the Beast" was ultimately sold to a stranger for $15,500.[337]

Both the song's film and single versions have been included on several compilation albums released by Disney, including The Music of Disney: A Legacy in Song (1992),[338] Classic Disney: 60 Years of Musical Magic (1995), Disney's Superstar Hits (2004),[339] Ultimate Disney Princess (2006), The Best Disney Album in the World ...Ever! (2006), and Now That's What I Call Disney (2011). In 2005, actress and singer Julie Andrews, a Disney Legend, included Lansbury's rendition of "Beauty and the Beast" on her album Julie Andrews Selects Her Favorite Disney Songs, although she does not cover the song herself;[340] the album is simply a compilation of Andrews' favourite Disney songs.[341]

Parodies

[edit]

The pilot episode of the animated TV series The Critic featured a minute-long "musical lampoon"[342] of the Beauty and the Beast ballroom sequence and song entitled "Beauty and King Dork", written and composed by The Simpsons writer Jeff Martin.[343] In the context of the episode, the unappealing protagonist Jay Sherman falls in love with a beautiful actress named Valerie, and this song is performed as they dance in his apartment where they are serenaded by a sentient vacuum cleaner and toilet.[344] AnimatedViews deemed it "a spot-on rendition" due to its use of singing furniture and "lavish" CGI-animated backgrounds.[345] Hollywood.com listed it in its article The Best Parodies of Disney Songs from Cartoons, writing " It's a quick one, but the inclusion of singing dust busters, a Mork and Mindy reference, and Jay Sherman's attempts to cover up the embarrassing lyrics make for one of the best gags on the list".[346] It was TelevisionWithoutPity's "favorite musical number" from the series.[347] Slant Magazine saw it as a "gut-busting parody".[348] CantStopTheMovies said the "nice scene" was "a bit crass" due to the singing toilet, yet had mostly "pretty great" lyrics.[349]

In Disney's fantasy film Enchanted (2007), the Jon McLaughlin ballad "So Close" serves as a "deliberate" reference to both the song and scene.[350] Because director Kevin Lima had always wanted to recreate the cinematography exhibited in Beauty and the Beast's ballroom sequence in live-action, an entire dance sequence was filmed to accommodate his vision.[351] In addition to being composed by Alan Menken, one-half of "Beauty and the Beast"'s songwriters, "So Close" was arranged by Robbie Buchanan, who arranged the Dion-Bryson single.[352]

In a duet with Jimmy Fallon, American singer Ariana Grande impersonated Dion while performing "Beauty and the Beast" live on the comedian's late-night talk show in 2015.[353] M Magazine deemed it "amazing",[354] while 2DayFM said "the singing is so good it gave me goosebumps".[355] SugarScape deemed it "pretty hilarious and surprisingly pretty much spot on".[356] Billboard said the duo "put their own spin" on the song, and that she "nailed her Celine impression".[357] NineMSN called it a "pitch-perfect rendition",[358] while Access Hollywood said she belted out the song like a diva.[359]

The ballroom sequence was parodied in an episode of Family Guy.[360]

See also

[edit]- Academy Award for Best Original Song

- Billboard Year-End Hot 100 singles of 1992

- Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song

- Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance

- Grammy Award for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals

- Grammy Award for Best Song Written for Visual Media

- Juno Award for Single of the Year

- List of Billboard Hot 100 top-ten singles in 1992

- List of UK top-ten singles in 1992

References

[edit]- ^ Khatchatourian, Maane (March 6, 2017). "Watch Ariana Grande and John Legend's 'Beauty and the Beast' Music Video".

- ^ a b Grande, Ariana (January 10, 2017). "🥀". Instagram. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Nessif, Bruna (January 10, 2017). "It Looks Like Ariana Grande and John Legend Are Teaming Up for a Beauty and the Beast Duet". E!. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (March 6, 2017). "Watch Ariana Grande, John Legend Cover 'Beauty and the Beast' Theme". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Watch the 'Beauty and the Beast' Theme Song Music Video". Time.

- ^ "How Angela Lansbury, the Original Mrs. Potts, Was Honored in Beauty and the Beast: A 30th Celebration". Peoplemag. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "See Shania Twain transform into Mrs. Potts for 'Beauty and the Beast: A 30th Celebration'". ABC News. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ a b "Bomb Threat Forces Jet to Land in Las Vegas". Los Angeles Times. October 6, 1990. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c Greenberger, Robert (October 2, 2010). "Alan Menken Revisits 'Beauty & The Beast'". ComicMix. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Tan, Corrie (March 24, 2015). "Alan Menken: Q&A with the music maestro behind Disney's Beauty And The Beast". The Straits Times. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Young, John (February 22, 2012). "Oscars 1992: Producer Don Hahn on how 'Beauty and the Beast' changed animation". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Angela Lansbury On Playing Mrs. Potts In BEAUTY AND THE BEAST. American Film Institute. April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Hischak, Thomas S. (2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. United States: McFarland. pp. 121–122. ISBN 9780786486946.

- ^ Brent, Dodge (2010). From Screen to Theme: A Guide to Disney Animated Film References Found Throughout the Walt Disney World(r) Resort. United States: Dog Ear Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 9781608444083.

- ^ a b c Gostin, Nicki (January 11, 2012). "Angela Lansbury Revisits Disney Classic 'Beauty And The Beast'". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "Toledo Blade". Toledo Blade. November 29, 1991. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c Flinner, Amanda (June 27, 2014). "Part of Their World: The Stories and Songs of 13 Disney Princesses". Songfacts. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Sands, Jez (October 25, 2010). "Beauty And The Beast: Paige O'Hara Interview". On the Box. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "Top 25 Disney Songs". IGN. August 9, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Hill, Jim (September 1, 2010). ""Tale as Old as Time" may make you fall in love with Disney's "Beauty and the Beast" all over again". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (2010). Tale as Old as Time: The Art and Making of Beauty and the Beast. United States: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-1423124818.

- ^ a b Galindo, Brian (July 15, 2013). "30 Things You Might Not Know About "Beauty And The Beast"". BuzzFeed. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Conradt, Stacy (June 11, 2016). "15 Things You Might Not Know About 'Beauty and the Beast'". Mental Floss. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Champion, Lindsay (March 1, 2014). "From 'A Whole New World' to 'Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah': We Rank Every Oscar-Winning Disney Song!". Broadway.com. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "Beauty & Beast". The Toledo Blade. November 29, 1991. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "'Beauty and the Beast' Composer Alan Menken on Rediscovering Lost Lyrics and Why He's "Shutting Up" About That Gay Character". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Ahi, Mehruss Jon; Karaoghlanian, Armen (2012). "Beauty and the Beast (1991) Director: Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise (Scene: 01:03:07 - 01:05:40)". Interiors. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Kehr, Dave (November 22, 1991). "Tame 'Beast' – Disney Film Falls Short Of The Classics". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Beth Fowler performing Beauty and the Beast. Seth Speaks. SiriusXM's Studios. April 17, 2012.

- ^ Galle, Deborah (December 11, 1994). "The Belle of the ice". The Beaver County Times. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c Monaco, Rachael (July 16, 2015). "Top 5 best song lyrics from the 1991 'Beauty and the Beast' movie soundtrack". AXS. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c Schwarzbaum, Lisa (January 12, 2012). "Beauty and the Beast 3D (2012)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "Greatest Disney Movie Songs". Femalefirst. May 1, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Gibron, Bill (October 5, 2010). "How 'Beauty and the Beast' Changed Oscar's Best Picture Race Forever". PopMatters. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Jennie, Punter (January 13, 2012). "Beauty and the Beast 3D: Disney classic gets added pop". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Ellison, Estefan (1991). "Beauty and the Beast". Estefan Films. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Anthony, Ross (March 17, 2004). "Interview with Beauty & the Beast Director – Kirk Wise". Ross Anthony. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Tracy, Joe (2001). "An Inside Look at the Original Beauty and the Beast". Digital Media FX. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Apodaca, Anthony A.; Gritz, Larry; Barzel, Ronen (2000). Advanced RenderMan: Creating CGI for Motion Pictures. United States: Morgan Kaufmann. p. 544. ISBN 9781558606180.

- ^ a b Anthony, Ross (February 2002). "Interview: 'Beauty and the Beast' Director Kirk Wise". Big Movie Zone. Archived from the original on October 30, 2002. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Moore, Roger (May 24, 2002). "The 'Spirit' Of Jeffrey Katzenberg". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Oscars (May 11, 2016). "25th Anniversary of Beauty and The Beast: The Ballroom" – via YouTube.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon (2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. United States: Wayne State University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780814330081.

- ^ Geraghty, Lincoln (2011). Directory of World Cinema: American Hollywood. United States: Intellect Books. p. 232. ISBN 9781841504155.

- ^ a b Sickels, Robert (2011). American Film in the Digital Age. United States: ABC-CLIO. p. 95. ISBN 9780275998622.

- ^ "7 Big Screen Moments That Are Still A Feast For The Eyes". CinemaBlend. January 13, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Fine, Marshall (January 11, 2012). "'Beauty and the Beast 3D': Classic that already has dimension". Hollywood & Fine. hollywoodandfine.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Rossing, Thomas D; Chiaverina, Christopher J (1999). Light Science: Physics and the Visual Arts. Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 258. ISBN 9780387988276.

- ^ Rocio, Maegan (November 27, 2012). "Alum dispels popular myth". The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Greenlee, Graham (2002). "Beauty and the Beast". The Digital Bits. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Robb, Brian J (2014). A Brief History of Walt Disney. United States: Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 9781472110725.

- ^ a b Pallant, Chris (2011). Demystifying Disney: A History of Disney Feature Animation. United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 98. ISBN 9781441150462.

- ^ Course Notes: Siggraph 1995, 22nd International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles Convention Center, Los Angeles, California, USA, Conference, 6-11 August 1995, Exhibition, 8-10 August 1995, Volume 4. United States: Association for Computing Machinery. 1995. p. 127.

- ^ a b c Berardinelli, James. "Beauty and the Beast (United States, 1991)". ReelViews. James Berardinelli. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ O'Hailey, Tina (2014). Hybrid Animation: Integrating 2D and 3D Assets. United States: CRC Press. ISBN 9781317965022.

- ^ a b c Chong, Andrew; McNamara, Andrew (2008). Basics Animation 02: Digital Animation. United Kingdom: AVA Publishing. pp. 84–87. ISBN 9782940373567.

- ^ a b c "Beauty and the Beast 3D". CinemaReview.com. 2. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Wegner, Timothy (1992). Image Lab. United States: Waite Group Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781878739117.

- ^ Anderson, Jeffrey M (1991). "Beauty and the Beast (1991)". Combustible Celluloid. Jeffrey M. Anderson. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Osmond, Andrew (2010). 100 Animated Feature Films. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 9781844575633.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Green, Dave (September 1992). "BEAUTY AND THE BEAST: WORK IN PROGRESS". Laser Rot. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Ferguson, Sean (October 7, 2010). "A Talk with Beauty and the Beast's Glen Keane". Why so Blue?. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Churchill, Alexandra. "50 Epic Things You Didn't Know About Disney Princesses". YourTango. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (December 31, 2001). "But It Was Big Enough Already". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Alter, Ethan (2014). Film Firsts: The 25 Movies That Created Contemporary American Cinema. United States: ABC-CLIO. p. 121. ISBN 9781440801884.

- ^ "25th Anniversary of Beauty and The Beast: The Ballroom". YouTube. Oscars. May 11, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (February 9, 2015). "Shall We Dance?: The Best Musical Sequences on Film". Movie Mezzanine. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Sito, Tom (2013). Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation. United States: MIT Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780262019095.

- ^ "The Most Important Movies of All Time: Beauty and the Beast". IGN. Ziff Davis. August 9, 2013. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ O'Hailey, Tina (November 26, 2014). Hybrid Animation. CRC Press. ISBN 9781317965022.

- ^ Josh, Larsen (1991). "Beauty and the Beast". Larsen on Film. J. Larsen. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ McLeroy, Leigh (2010). The Beautiful Ache. United States: Lucid Books. ISBN 9781935909002.

- ^ Cook, Matthew Thomas (2007). A 3-dimensional Modeling System Inspired by the Cognitive Process of Sketching. United States. p. 139. ISBN 9780549144847.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[permanent dead link] - ^ a b c Lucas, Chris (February 11, 2015). "Ten Romantic Disney Moments (Frozen not included)". Moviepilot. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Top 100 Movie Moments". IGN. Ziff Davis. Retrieved June 8, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Beauty and the beast - Angela Lansbury Chords - Chordify". chordify.net. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Beauty and the Beast – By Angela Lansbury - Digital Sheet Music". Musicnotes.com. Walt Disney Music Publishing. April 2, 2007. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ a b "Beauty and the Beast (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) – Various Artists". iTunes. Apple Inc. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Dequina, Michael (January 1, 2002). "Beauty and the Beast Large Format Special Edition (G)". The Movie Report. Michael Dequina.

- ^ Canavese, Peter (1991). "Beauty and the Beast (1991)". Groucho Reviews. Peter Canavese. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Whitty, Stephen (January 13, 2012). "Back to 'The Beast': Disney tinkers with an old favorite". NJ.com. New Jersey On-Line. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 22, 1991). "Beauty And The Beast". Roger Ebert. Ebert Digital. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Hischak, Thomas S; Robinson, Mark A (2009). The Disney Song Encyclopedia. United States: Scarecrow Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780810869387.

- ^ a b c d Zafar, Aylin (April 21, 2014). "The Definitive Ranking Of The 102 Best Animated Disney Songs". BuzzFeed. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c Siskel, Gene (November 22, 1991). "'Beauty And The Beast' Has A Song In Its Heart". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Cheang, Michael (June 12, 2014). "'The Lion King' turns 20: Celebrating Disney's greatest musical moments". The Star. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Unterberger, Andrew (February 19, 2015). "Every Oscar Winner for Best Original Song, Ranked". Spin. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c "30 best Disney songs in history". GamesRadar. Future US, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ "Beauty And The Beast". TV Guide. CBS Interactive Inc. 1991. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Shaffer, R. L (October 18, 2010). "Beauty and the Beast: Three-Disc Diamond Edition Blu-ray Review". IGN. Ziff Davis. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler W (2000). Film Genre 2000: New Critical Essays. United States: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791445143.

- ^ a b c Cole, Jake (October 10, 2010). "Not Just Movies". Not Just Movies. Jake Cole. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Verhoeven, Beatrice (November 18, 2016). "20 Facts You Didn't Know About 1991's 'Beauty and the Beast' for 25th Anniversary (Photos)". The Wrap. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Block, Tara (June 18, 2015). "Feel the Love Tonight With This Romantic Disney Playlist". PopSugar. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ "Fall in Love with 30 Disney Love Songs". Musicnotes.com Blog. February 12, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Damon (March 5, 2012). "FILM REVIEW: Beauty and the Beast". Chichester Observer. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Christa. ""Beauty and the Beast" is DA BOMB!". Debbie Twyman and Craig Whitney. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Brooks, Linda Ruth (2010). I'm Not Broken, I'm Just Different. United Kingdom: Linda Ruth Brooks. ISBN 9780646529233.

- ^ "Review: Beauty and the Beast 3D". JoBlo. January 13, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast by Celine Dion". Songfacts. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Osmanski, Stephanie. "M's Ultimate List: Top 20 Disney Songs of All Time". M. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Ayres, Brenda (2003). The Emperor's Old Groove: Decolonizing Disney's Magic Kingdom. United States: P. Lang. p. 86. ISBN 9780820463636.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast". Howard Ashman. Shoptalk Ltd. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ Griswold, Jerry (2004). The Meanings of "Beauty and the Beast": A Handbook. Canada: Broadview Press. p. 252. ISBN 9781551115634.

- ^ Porto, Lucía Loureiro. The Translation of the Songs in Disney's "Beauty and the Beast": an example of Manipulation (PDF). p. 134. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2015.