Kurigalzu II

| Kuri-Galzu II | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon | |

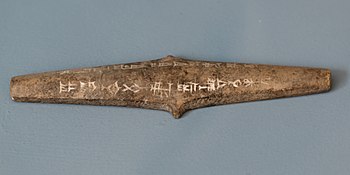

Dagger of king Kurigalzu II, Istanbul Archaeological Museum | |

| Reign | 25 regnal years 1332–1308 BC |

| Predecessor | Burna-Buriaš II Kara-ḫardaš Nazi-Bugaš |

| Successor | Nazi-Maruttaš |

| House | Kassite |

Kurigalzu II (c. 1332–1308 BC short chronology) was the 22nd king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty that ruled over Babylon. In more than twelve inscriptions, Kurigalzu names Burna-Buriaš II as his father. Kurigalzu II was placed on the Kassite throne by the Assyrian king Aššur-Uballiṭ I, reigned during a period of weakness and instability for twenty five years, eventually turning on his former allies and quite possibly defeating them at the battle of Sugagu. He was once thought to have been the conqueror of the Elamites but this now tends to be assigned to the earlier king of this name, together with the Chronicle P account.[1]

There is a gap of a little over forty years between his reign and that of his earlier namesake, Kurigalzu I and, as it was not customary to assign regnal year numbers, and they both had lengthy reigns, this makes it exceptionally difficult to distinguish for whom an inscription is intended.[2] A few royal inscriptions are clearly assignable to Kurigalzu II since they give the name of his father, Burna-Buriaš, but these record either the dedication of objects, such as eye stones, beads, axe-heads, etc., or appear on the cylinder seals of his servants, such as the accountant, Uballissu-Marduk. 167 economic texts, mostly from Nippur, are assigned to him based on the style of the date formula and record up to the 24th year of his reign.[2] An inscribed brick of Kurigalzu II was found at Dur-Kurigalzu.[3]

Reign

[edit]Accession

[edit]

According to an Assyrian chronicle Kurigalzu II owed his throne to the Assyrians. Burna-Buriaš’ brief successor, Kara-ḫardaš, had been murdered during a coup d'état by the Kassite army, who had elevated an otherwise unremarkable Nazi-Bugaš to the throne. This incited the intervention of the Assyrian monarch Aššur-Uballiṭ, whose daughter Muballiṭat-Šērūa was either the mother or the consort of Kara-ḫardaš.[4][5][6] The usurper was unceremoniously executed and Kurigalzu was installed as a king in his youth from the royal lineage. His genealogical relationship with the Assyrian king is not known.[7]

Despite this, there was a tradition of military conflict between Babylon and Assyria around this time. Perhaps as he matured he came to resent his erstwhile benefactors and the accession of Enlil-nīrāri to the Assyrian throne may have assisted loosening the ties of loyalty. A fragmentary letter lists booty brought into Babylonia by Kurigalzu.[8]

A copy of an inscription[i 1] commemorates the gift of a votive sword to the god Ninurta, for his divine intervention in bringing to justice the perpetrators of a massacre of Nippur citizens, in the courtyard of the e-sag-dingir-e-ne, probably meaning "the House of the Great Lord," which appears to have been the most important temple of Dur-Kurigalzu or perhaps its otherwise unknown Nippur namesake. It records, “a certain somebody mobilized a wicked foe in the mountains, who had no name and held no gods precious, and took troops from Dēr to be his allies, and sent (them), and had (them) draw blades … and spilled like water the blood of Nippur’s citizens.”[9] In some respects, these events are reminiscent of the Chronicle P passage concerning Kurigalzu’s exploits against Ḫurba-tila, now assigned to his earlier name-sake.

Battle of Sugagu

[edit]Two chronicles report a conflict, called the battle of Sugagu, only a day's journey south of Aššur[10] on the Tigris and therefore deep in Assyrian territory, between Kurigalzu II and his Assyrian contemporary resulting in exchange of territory.[11] One proclaims Kurigalzu the victor

He (Kurigalzu) went to conquer Adad-nīrāri, king of Assyria. He did battle against him at Sugaga, which is on the Tigris, and brought about his defeat. He slaughtered his soldiers and captured his officers.

— Chronicle P, Column 3, lines 20 to 22.[i 2]

but confuses the Assyrian adversary with his more famous descendant, while the other declares victory to Enlil-nīrāri

At Sugagi, which is on the Tigris, Enlil-nīrāri, king of Assyria, fought with Kurigalzu. He brought about his total defeat, slaughtered his troops and carried off his camp. They divided the districts from Šasili of Subartu, to Karduniaš into two and fixed the boundary-line.

— Synchronistic Chronicle, tablet A, lines 19 to 23.[i 3]

suggesting a loss of territory from Assyria to Babylon.[12] The epic texts seem to be biased to their respective authors’ homelands in a rather typical genre for this period and taken together may perhaps suggest an indecisive outcome. A second battle, this time at Kilizi, near Erbil, is recorded on a fragment.[i 4] A later kudurru of Kaštiliašu IV recalls Kurigalzu’s gift of a large area of land to Uzub-Šiḫu or -Šipak in grateful recognition of his service in the war against Assyria.

The dream of Kurigalzu

[edit]

A zaqiqu, or incubation omen, is known from this period as the dream of Kurigalzu and the tablet of sins, where a Kassite king tentatively identified with him seeks through a dream to find out why his wife cannot bear a child:

Kurigalzu went into Esagila [ … ], the spirits approached him and anxiety … When he fell asleep on his couch Kurigalzu saw a dream. In the mourning, at sunrise, he made [a report (?)] to his courtiers: “This night, o courtiers, I joyfully beheld Bel! Nabû, who was standing before him, set up (?) the Tablet of Sins [ … ].[13]

— The dream of Kurigalzu[i 5]

Inscriptions

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ F. Vallat (2000). "L'hommage de l'élamite Untash-Napirisha au Cassite Burnaburiash". Akkadica (114–115): 109–117.

- ^ a b J. A. Brinkman (1976). "Kurigalzu". Materials for the Study of Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 205–246. especially pages 205 - 207.

- ^ Walker, C. B. F. “A Duplicate Brick of Kurigalzu II.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 32, no. 4, 1980, pp. 247–48

- ^ Podany, Amanda H. (2022). Weavers, Scribes, and Kings A New History of the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. p. 390. ISBN 9780190059040.

- ^ Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East History, Society and Economy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134750917.

Burnaburiash, unable to obtain an Egyptian princess, gladly accepted the Assyrian king's daughter, Muballitat-Sherua, as daughter-in-law

- ^ The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117. Brill. 2020. pp. 207–208. ISBN 9789004430921.

- ^ J. A. Brinkman. "The chronicle tradition concerning the deposing of the grandson of Aššur-Uballiṭ". MSKH I. pp. 418–423.

- ^ Benjamin R. Foster (2009). Carl S. Ehrlich (ed.). From an Antique Land: An Introduction to Ancient Near Eastern Literature. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 201.

- ^ A. R. George (2011). Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection. CDL Press. pp. 117–118.

- ^ C. J. Gadd (1975). "XVIII: Assyria and Babylon". In I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond; S. Solberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume II, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region, 1380 – 1000 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32.

- ^ H. W. F. Saggs (2000). Babylonians. p. 117.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Glassner (2004). Benjamin Read Foster (ed.). Mesopotamian chronicles. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 50.

- ^ Irving L. Finkel (1983). "The Dream of Kurigalzu and the Tablet of Sins". Anatolian Studies. 33: 75–80. doi:10.2307/3642694. JSTOR 3642694. S2CID 191391384.