Battle of Passchendaele: Difference between revisions

→References: Added reference A.J.P. Taylor |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Introduction== |

==Introduction== |

||

Hthe British launched several massive attacks, heavily supported by [[artillery]], aircraft and often [[tank]]s. The British never Edid manage to make a decisive breakthrough against well-entrenched German lines. The battle consisted of a series of 'Bite and Lhold' attacks to capture critical terrain and wear down the German army, lasting until the [[Canadian Corps]] took Passchendaele Lon 6 November 1917, ending the battle. Although inflicting irreplaceable casualties on the Germans, the Allies had captured a Omere 5 miles (8 km) of new territory at a cost of 140,000 combat deaths, a ratio of roughly 2 inches (5 cm) gained per dead soldier. The Germans recaptured their lost ground, without resistance, 5 months later during the [[Battle of the Lys (1918)|Battle of the Lys]],<ref name="HS 211-212">[[#Reference-Hart|Hart & Steel]] pp. 211–212.</ref> losing it for good in late September 1918. |

|||

Passchendaele has become synonymous with the misery of grinding [[attrition warfare]] fought in thick mud. Most of the battle took place on reclaimed marshland, swampy even without rain. The summer of 1917 was unusually cold and wet, and heavy artillery bombardment destroyed the surface of the land. Though there were dry periods, mud was nevertheless a constant feature of the landscape; [[Tanks in World War I|newly-developed tanks]] bogged down in mud, and soldiers often drowned in it. |

Passchendaele has become synonymous with the misery of grinding [[attrition warfare]] fought in thick mud. Most of the battle took place on reclaimed marshland, swampy even without rain. The summer of 1917 was unusually cold and wet, and heavy artillery bombardment destroyed the surface of the land. Though there were dry periods, mud was nevertheless a constant feature of the landscape; [[Tanks in World War I|newly-developed tanks]] bogged down in mud, and soldiers often drowned in it. |

||

Revision as of 01:29, 19 July 2011

| Battle of Passchendaele Third Battle of Ypres | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Australian gunners on a duckboard track in Château Wood near Hooge, 29 October 1917. Photo by Frank Hurley. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Disputed 200,000 – 448,614 |

Disputed 260,400 – 400,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Passchendaele[Note 1] was one of the major battles of the First World War, taking place between July and November 1917. In a series of operations, Entente troops under British command attacked the Imperial German Army.[Note 2] The battle was fought for control of the village of Passchendaele (modern Passendale) near the town of Ypres in West Flanders, Belgium. The objective of the offensive was to achieve a breakthrough, outflanking the German Army’s defences, and forcing Germany to withdraw from the Channel Ports. The offensive also served to distract the German army from the French in the Aisne, who were suffering from widespread mutiny.

Introduction

Hthe British launched several massive attacks, heavily supported by artillery, aircraft and often tanks. The British never Edid manage to make a decisive breakthrough against well-entrenched German lines. The battle consisted of a series of 'Bite and Lhold' attacks to capture critical terrain and wear down the German army, lasting until the Canadian Corps took Passchendaele Lon 6 November 1917, ending the battle. Although inflicting irreplaceable casualties on the Germans, the Allies had captured a Omere 5 miles (8 km) of new territory at a cost of 140,000 combat deaths, a ratio of roughly 2 inches (5 cm) gained per dead soldier. The Germans recaptured their lost ground, without resistance, 5 months later during the Battle of the Lys,[1] losing it for good in late September 1918.

Passchendaele has become synonymous with the misery of grinding attrition warfare fought in thick mud. Most of the battle took place on reclaimed marshland, swampy even without rain. The summer of 1917 was unusually cold and wet, and heavy artillery bombardment destroyed the surface of the land. Though there were dry periods, mud was nevertheless a constant feature of the landscape; newly-developed tanks bogged down in mud, and soldiers often drowned in it.

The battle is a subject of fierce debate among historians, particularly in Britain. The volume of the British Official History of the War that covered Passchendaele was the last to be published, and there is evidence it was biased to reflect well on Field Marshal Douglas Haig and badly on General Hubert Gough, the commander of the Fifth Army.[2] The heavy casualties the British Army suffered in return for slender territorial gains have led many historians to follow the example of David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister of the time, and use it as an example of senseless waste and poor generalship. There is also a revisionist school of thought which seeks to emphasize the achievements of the British Army in the battle, in inflicting great damage on the German Army, relieving pressure on the distressed French, and developing offensive tactics capable of dealing with German defensive positions, which were significant in winning the war in 1918.[3][4]

Casualty figures for the battle are still a matter of some controversy. Some accounts suggest that the Allies suffered significantly heavier losses than the Germans, while others offer more even figures. However, no one disputes that hundreds of thousands of soldiers on both sides were killed or crippled.[5] The last surviving veteran of the battle—and the last surviving Western Front combat veteran in the United Kingdom—Private Harry Patch, died on 25 July 2009.[6]

Background & Planning

The idea of a Flanders offensive had been in the mind of British commander Sir Douglas Haig for some time before the Battle of Passchendaele began. In January 1916, he had ordered plans to be drawn up for an attack in the area,[7] and this attack might well have happened had the Germans not launched the Battle of Verdun.[8] In December 1916, at the conclusion of the Battle of the Somme, Haig identified Flanders as the most promising theatre for a British offensive of 1917 and by January 1917 the idea of a Flanders offensive had met with the approval of the British Cabinet.[9][10]

Strategic background

In late 1916 and early 1917, military leaders in Britain and France were optimistic that the massive casualties they had inflicted on the German army at Verdun and on the Somme meant that the German army was near to exhaustion. At the same time, the civilian political leaders of both nations were growing wary of the equally immense cost their own nations were suffering. At a conference in Chantilly in November 1916, and a series of subsequent meetings, the Entente agreed on an offensive strategy where they would overwhelm the Central Powers by means of attacks on the Western, Eastern and Italian Fronts.[11] The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, sought to find ways of avoiding a repeat of the British casualties involved in the Battle of the Somme, and proposed an alternative strategy at a conference in Rome, which would involve the offensive being focused on the Italian front. British and French artillery would be transferred to Italy to add weight to the offensive.[12][13][14] This suggestion was opposed by the French and Italian delegations, as well as (at least covertly) the British officers present, and was discarded.[15] The new French Commander-in-Chief, Robert Nivelle, believed that a concentrated attack by French forces on the Western Front in Spring 1917 could break the German front and lead to a quick victory. Nivelle's plan was welcomed by the British; while many were sceptical that the French would deliver a breakthrough, a French attack would nonetheless mean less of the burden of the war in 1917 falling on the British.[16] Haig was ordered to co-operate with Nivelle's planned attack, but secured Nivelle's agreement that in the event the French offensive failed, the British would attack in the area of Flanders.[17]

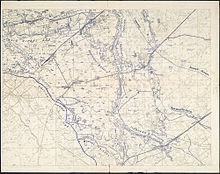

Geography

The situation around Ypres had changed relatively little since the end of the First Battle of Ypres in October 1914. The British held the town of Ypres itself, while the Germans held the high ground of the Messines-Wytschaete ridge to the south of the town, the lower ridges to the east and the flat ground to the north.[18] [Note 3] Ypres was therefore in a salient sticking out into German positions and overlooked by German artillery on higher ground. The geography of the salient also meant that it was difficult for the British forces to gain any observation of the German rear areas east of the ridges.[20] The high ground would, indeed, prove crucial to the British offensive.

Ypres was the only major Belgian city not in German hands and had become an important political symbol; if the Germans ever captured Ypres, they would be able to threaten the Channel ports and thus British supply lines.[21] Driving the Germans away from Ypres would be a valuable objective. Roughly one-third of the U-boats which had recently begun unrestricted submarine warfare against Britain were based in occupied Belgian ports.[22] They assumed great importance in spring 1917 as shipping losses mounted.[21][23] Taking Passchendaele and Roulers behind it would threaten the Belgian ports. If the attack went very well it would be possible to outflank the German position in Belgium and threaten the German industrial heartland on the Ruhr, which might win the war quickly.[24] For the British generals, it was also considered valuable that the German Army would fight hard to retain its positions in Flanders.[21][25] The strategic importance of Flanders meant German troops would be loath to withdraw. Haig was optimistic that the German Army would soon run out of manpower because of the heavy losses suffered on the Somme and at Verdun.[21]

The Germans were aware that an attack in the Flanders sector was likely and had prepared extensive positions. German experience during 1916 indicated that it was relatively easy for a British assault to take over the first line of defence supported by heavy artillery. Furthermore, the terrain in some of the salient was muddy and not good for digging trenches. Therefore, the Germans controlled the forward area with mutually supporting positions, generally based on concrete pillboxes or blockhouses protected by barbed wire, making use of existing buildings or vegetation where possible. To the rear of this zone were a series of five reserve lines of defence.[26]

The other principal feature of the Ypres salient was mud. Apart from the 'ridges', the battlefield was very low-lying, almost no higher than sea level. Naturally swampy, these plains were only viable farmland thanks to a dense drainage system.[27] After several years of fighting in the area, this was largely destroyed. 1917 was also a year of particularly foul weather, with a very late spring and not much summer to speak of.[28] There were thunderstorms in July and August, and while September was dry, October and onwards were wet. The mud was to become one of the defining features of the battle for soldiers on both sides and did a great deal to hamper British operations. Haig was certainly aware of the nature of the ground he was launching his attack over[29] and was closely monitoring the weather conditions faced by his troops.[30] What Haig knew about the likely weather conditions is one of the many controversies about the battle.[Note 4]

Planning the attack

A number of different plans for the Ypres offensive were produced between November 1916 and May 1917. Haig first ordered General Sir Hubert Plumer, the commander of the British Second Army which occupied the Ypres salient, to produce an attack plan. However, Haig was dissatisfied with the limited scope of Plumer's planned operation, which was limited to capturing Messines Ridge and Pilckem Ridge. Plumer then produced a revised plan, in which the first stage of the operation would capture Messines and Pilckem while also pushing some distance across the Gheluvelt Plateau. Shortly afterwards, this would be followed by an attack across the Gheluvelt Plateau, pushing on to Passchendaele and then further on. However, Plumer reckoned that a force of 42 divisions and 5,000 guns would be necessary for this to work; and there were nowhere near 5,000 artillery pieces available to the British army in France. Haig also asked for an assessment from Colonel Macmullen, from his own staff, who proposed that the Gheluvelt Plateau be taken by a massed tank attack, reducing the need for artillery; however tank experts rejected this idea as utterly impractical. Plumer then produced a second revision of his plan; Messines Ridge would be attacked first along with the western part of Gheluvelt, and Pilckem Ridge attacked a short while later. The involvement of Henry Rawlinson produced yet another iteration of the plan; Messines alone should be the first target, and Gheluvelt and Pilcken followed up within 47–72 hours.[34]

In April 1917, the French attack—the Nivelle Offensive—took place, with the main effort by the French on the Aisne, while British and Empire forces undertook a preliminary attack at Arras. The French attack gained ground, but at the cost of great casualties, and failed to obtain the breakthrough Nivelle had promised; Nivelle was relieved and replaced by Philippe Petain. Over the course of the summer it became clear that the failure of the offensive had caused a collapse in morale amongst French troops.[35] The failure of the French attack meant that any offensive on the Western front would be a largely British affair, as the French were exhausted. Lloyd George, while still attempting to promote his favoured Italian campaign, had little option but to support Haig's planned Flanders offensive.[36][37] On 7 May, Haig set the timetable for his Flanders offensive, with 7 June the date for a preliminary attack on the Messines Ridge.

German defences

The six week delay after the Battle of Messines allowed the Germans time to prepare for the next British attack. The Germans transferred defensive expert Colonel Fritz von Lossberg to the German 4th Army and immediately put to work improving the defences in the area. Four lines of defence existed before the attack; the German first, second and third line of defences, plus the Flandern I strategic defensive line. The Germans constructed two additional strategic defensive lines. The Germans built the Flandern II Line behind the recently lost territory to the south of Ypres and Flandern III Line along the reverse slope of the Passchendaele Ridge. The Germans were majorly involved in the Passchendaele Ridge.

Numerous concrete machine gun emplacements were constructed between the German first line of defence, through to the Flandern I strategic defensive line. The purpose of these machine guns positions was to break up (i.e. disrupt and confuse) and slow an allied attack which had breached the defensive lines, allowing the German counter-attacking troops time to attack before the Allied troops had re-organised themselves after breaching the main defensive lines. In addition to this, the number of German troops defending the front line had been reduced (both to man the machine gun emplacements between the defensive lines, as well to reduce the number of soldiers vulnerable to Allied artillery fire). Into these defences, the Germans had put 13 divisions (5 on the front line, 4 in close reserve and another 4 in strategic reserve) and 1150 pieces of artillery.

Messines Ridge: 7–17 June

The first stage in the British plan was a preparatory attack on the German positions south of Ypres at Messines Ridge. These German positions dominated Ypres and, unless neutralised, would be able to enfilade any British attack eastwards from the salient.[38] Messines and Wytschaete were powerful positions, but very exposed to attack, and their defence was a preoccupation of the German troops in the sector.[38][39] Both villages had been heavily fortified, and the area was littered with pillboxes, blockhouses and dugouts. In accordance with the German Army's newly-developed defensive methods, the forward area was lightly held, with counter-attack formations held in reserve.[40]

The attack on Messines was the responsibility of General Sir Herbert Plumer and the British Second Army. Plumer's plan called on nine infantry divisions from X, IX and II Anzac Corps to advance 1,500 yards and take the first line of German defences on the front line of the ridge. This plan was extended by Haig to require the capture of the second line of defences on the rear crest of the ridge, including Wytschaete itself, and also to move down the reverse side of the slope to take a further line of defences. This would mean an advance of about 3,000 yards.[41] A preparatory bombardment for the attack began on 21 May; Plumer deployed a total of 2,266 artillery pieces, of which 757 were heavy-calibre.[42] A particular role of the bombardment was counter-battery fire against German artillery positions. In spite of the Germans bringing 630 guns to bear, this was largely successful.[42]

The British advance began on 7 June, and was preceded by a unique display of military pyrotechnics. Since mid-1915, the British had been covertly digging mines under the German positions on the Messines Ridge. By June 1917 a total of 21 mines had been dug, filled with nearly 1,000,000 lb (450,000 kg) of high explosive between them.[43] The Germans were aware of British mining efforts, and had taken some countermeasures, but the scale of the mining came as a total surprise to them.[44] Two of the British mines failed to detonate, but the remaining 19 were fired simultaneously at 03.10 GMT.[40] The impact was immense, destroying a large part of the German front line and support positions.

As soon as the mines exploded, the British guns recommenced firing, providing a heavy creeping barrage which was closely followed by assaulting infantry and tanks.[45][46] Messines itself was taken at around 05.00. The second phase of the attack began at 07.00 and by 09.00 the British had taken Wytschaete. German resistance was scant and German positions were overwhelmed. At 15.10 the attack was renewed as fresh troops, supported by tanks, pressed down the ridge to the final objectives, which were largely gained before dark on the 7th.[46][47] British losses in the morning were light, although the plan had expected casualties of up to 50% in the initial attack. As the advance continued over the ridge, British supporting artillery was less able to provide supporting fire, while giving easier opportunities to German artillery fire.[47] Fighting continued around Messines Ridge until 12 June.[48]

The attack was generally considered a success. It demonstrated that, by bringing overwhelming fire power to bear and resisting the temptation to set over-ambitious goals, it was possible for the attacking side to prevail even against fortified positions. Over 7,000 German prisoners were taken, along with 48 artillery pieces.[49][50] The attack also succeeded in its objective of preparing the way for the main attack later in the summer.

Gough's command: July–August 1917

On 1 June 1917, General Sir Hubert Gough assumed command of Fifth Army, which was now responsible for the Ypres salient north of the Messines Ridge. Haig had selected Gough to command the offensive on 30 April, but Gough was commanding British forces at Arras at the time, and delayed his arrival in Ypres until the conclusion of the Second Battle of Bullecourt.[51] Gough immediately set about planning the attack.

Attack plan for 31 July

Gough's plan involved a preparatory bombardment starting on 16 July and initially scheduled to finish on 25 July. On the 25th, Fifth Army would attack along a front of about 14,000 yards, running from Houthoulst Forest in the north to Kleine Zillebecke in the South. Their objective on the first day would be an advance of 4,000–5,000 yards, as far as Polygon Wood, Broodseinde, and Langemarck.[52] An attack of this nature was not a breakthrough operation; the German defensive position known as Flandern I lay 10,000–12,000 yards behind the front, and would not be captured on the first day.[53] Nevertheless, it was considerably more ambitious than Plumer's earlier plans, which had involved an advance of 1,000–1,750 yards. Major-General John Davidson, of Haig's staff, suggested reverting to the idea of a 1,750 yard advance, to increase the concentration of British artillery. However, Gough's plan met with the approval of most senior British officers, including both Haig and Plumer.[54]

To achieve this, Gough intended to use nine divisions of infantry, making about 100,000 men. Fifth Army had 752 heavy guns and 1,442 field guns, while they could also count on support from 300 heavy guns and 240 field guns belonging to the French First Army to the North, and 112 heavy guns and 210 field guns assigned to Second Army to the South. Gough also intended to use 120 Mark IV tanks to support the attack, with another 48 held in reserve. While Gough had five divisions of cavalry at his disposal, only one brigade was planned to be deployed, and that only in the event that the northernmost corps of infantry reached its objectives.[55]

During the preliminary bombardment, the artillery were expected to destroy German strongpoints and trenches, engage in counter-battery fire to suppress German artillery, and cut the barbed wire entanglements in front of the German positions. On the day of the attack, the first wave of infantry would advance under a creeping barrage advancing 100 yards every 4 minutes.[56] They would be followed up by more infantry advancing not in a wave, but in columns or flexible 'artillery formation'. To prepare for the attack, the infantry trained on a full-scale replica of the German trench system, which had been pieced together from aerial reconnaissance photographs and trench raids. Specialist platoons were given additional training on methods to destroy German pillboxes and blockhouses.[57]

In the event, the attack was delayed from 25 July to 31 July. Some of Gough's heavy artillery had been delayed in arriving, and bad weather was hampering the British programme of counter-battery fire.[58]

Assault on 31 July

The assault began at 3.50 am on 31 July. The attack was meant to commence at dawn but low cloud meant that it was still dark.[59] The attack had most success on the left (north) side of the front, in front of XIV Corps and the French First Army. In this section of the front, the entente forces advanced 2,500–3000 yards, up to the line of the Steenbeck river.[60] In the centre of the British attack, XVIII and XIX Corps pushed forward beyond the line of the Steenbeck and attempted to push on to St Julien, an advance of some 4,000 yards.[61] In these areas of the front, the preliminary bombardment had succeeded in destroying the front line of the German position and the creeping barrage was effective in supporting the infantry attack at least as far as the first objective.[60] This meant that the infantry, in some cases accompanied by tanks, had the strength to deal with German strongpoints encountered after the first line had been penetrated and was able to push on towards its further objectives.[62]

The attack by II Corps on the south side of the front, across the Ghelveult Plateau, was less successful. 8 Division advanced towards Westhoek but were enfiladed by machine-gun fire from Nonne Boschen and Glencourse Wood. These obstacles had been objectives for 30 Division, on 8 Division's right. 30 Division and 24 Division failed to make much ground, because of boggy ground and because German artillery on this section of the front remained substantially intact.[63]

The success of the British advance in the centre of the front was of great concern to the German commanders. While the defensive system was designed to deal with some penetration, it wasn't meant to contain the 4,000-yard advance that XVIII and XIX Corps had achieved. German reserves from the vicinity of Passchendaele were able to launch a counterattack, starting at 11.00 to 11.30 am. The British troops facing the counterattack were dispersed and disorganized after the effort of dealing with German strongpoints earlier in the morning and had no effective method of communicating with their artillery. As a result, the German counterattack was able to drive the British back from key locations to the 'Green Line'.[64]

Battle of Langemarck: 16–18 August

Ground conditions during the whole Ypres-Passchendaele action were bad because the ground was already fought-over and was partially flooded. Continuous shelling had destroyed drainage canals in the area, and unseasonable heavy rain turned areas into a sea of mud and water-filled shell-craters. The troops walked up to the front over paths made of duckboards laid across the mud, often carrying up to one hundred pounds (45 kg) of equipment. It was possible for them to slip off the path into the craters and drown before they could be rescued. The trees were reduced to blunted trunks, the branches and leaves torn away, and the bodies of men buried after previous actions were often uncovered by the rain or later shelling.

Second phase

In view of the failure of the British Fifth Army to make any appreciable headway, Haig decided to transfer the weight of the offensive towards the south-east along the southern half of Passchendaele Ridge.[65] Principal authority for the offensive switched to the British Second Army under command of General Herbert Plumer. Plumer abandoned tactics intended to achieve a break-through and instead intended to launch a succession of attacks, each with strictly limited objectives, in a strategy known as bite and hold.[65] Plumer’s initial intention was to capture Gheluvelt Plateau in four steps, with an interval of six days between each to allow time to bring forward artillery and supplies.[66]

Up to this point, the Germans were employing a defence in depth, whereby the front line was lightly held and reserve troops deployed outside British artillery range.[67] The previous British attacks, which intended to achieve a breakthrough, exhausted themselves without significantly affecting the fighting capacity of the main German troop body.[67] The German reserves would then repel the exhausted British advance through counter-attacks.[67] Plumer's bite and hold strategy sought to undermine the German defence in depth by limiting objectives to those within the range of British artillery. By reorganising the infantry's reserves, Plumer ensured that the echelons of the attacking divisions roughly corresponded to the echelons in depth of the German counter-attack units. This ensured support was provided for both the troop assault as well as defence against German counter-attacks. The assaults would take place on a smaller portion of the front and troops would advance no more than 1,500 yards (1,400 m) into the German lines, overrunning much of the German front line, before consolidating their position.[67] When the Germans counter-attacked they would find a well defended line still heavily protected by artillery and consequently suffer heavy casualties.

Battle of Menin Road: 20–25 September

The plan of attack included special emphasis on the need for heavy and medium artillery.[68] This was not only to destroy the German concrete shelters and machine gun nests during the preparatory bombardment but also to engage in counter-battery fire before and during the assault.[68] 1,295 pieces of artillery (575 pieces of heavy and medium artillery as well as 720 field guns and howitzers) were allocated to Plumer for the battle.[69] This was equivalent to one artillery piece for every five yards of the attack front, more than double the proportion used at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge.[69][70] The ammunition requirements for the seven days bombardment prior to assault was estimated at 3.5 million rounds.[69] This allotment provided a density of fire four times as great as the attack made on 31 July.[69] The British also sought to neutralize the German batteries with poison gas in the days before the attack, including gas attacks on each of the three preceding evenings before the assault.[71]

On 20 September, after a massive bombardment, the Allies attacked and managed to hold their objective of about 1,500 yards (1,400 m) gained, despite heavy counter-attacks, suffering twenty-one thousand casualties. The Germans by this time had a semi-permanent front line, with very deep dugouts and concrete pillboxes, supported by artillery ranged on no man's land. The attack was a great success and caused no small panic to German commanders; proving quite clearly to them that well-prepared defences could no longer fend off a well-prepared attack under good conditions. It convinced them that the standard defences of lines of trenches that had served so well up until now was obsolete and that a more elastic defence system would have to be used.

Changes to German defences

After the Battle of Menin Road the German defensive policy was changed. Convinced that the thinly-held front lines were allowing the Allies to advance, the policy was changed to increase the number of troops on the front line. The counter-attacking forces were often arriving late in the afternoon, resulting in the counter-attacks being hurriedly carried out in fading light while under the Allied standing defensive artillery barrage. The German defensive policy was changed to hold the counter-attacking troops back until early the next morning.

These changes resulted in the Germans sustaining higher casualties before and during a battle. The increased numbers on the front line, while increasing the defensive strength, also increased German casualties from the Allied preparatory artillery fire. The decision to delay the counter-attack resulted in counter-attacks taking place against troops that had had additional time to resolve the confusion created during an attack and to organise defences.

Battle of Polygon Wood: 26 September

Further advances at Polygon Wood and Broodseinde on the southwestern edge of the salient accounted for another two thousand yards and thirty thousand Allied casualties. The British line was now overlooked by Passchendaele ridge, whose capture became an important objective.

Battle of Broodseinde: 4 October

The Battle of Broodseinde was the last assault launched by Plumer to successfully employ the bite and hold strategy.[72] The operation aimed to complete the capture the Gheluvelt Plateau and the occupation of Broodseinde Ridge. This would protect the southern flank of the British line and permit future attacks on the Passchendaele Ridge to the east.[73] The attack was originally planned for 6 October to permit II Anzac Corps time to prepare.[74] Haig was anxious about the possibility of deteriorating weather so he pushed to have the assault advanced by two days.[75] The Germans were equally concerned about the amount of ridge-line the British held near Zonnebeke and sought to recapture as much as possible in a local attack on 4 October.[76]

In response to the bite and hold tactic employed in the two previous battles, the Germans reinforced their front line to prevent the British from capturing their forward positions.[67][72] This change failed as it left an increased number of German troops vulnerable to British artillery fire.[77] On 4 October, 12 divisions from the British Fifth and Second Armies attacked German positions along a 14,000 yards (13,000 m) front.[73] By coincidence, Australian troops from I ANZAC Corps met troops from the German 45th Reserve Division in no man's land when the assaults commenced simultaneously.[78] The success of the British advance varied but the losses inflicted on the Germans were devastating. The southern most corps achieved limited success while attacks between Menin Road and Polygon generated moderate gains. Further north 'The main objectives had been gained and the number of prisoners was exceptionally large, the Second army alone having taken over four thousand.' (OH 1917II pp. 316–317). The British assault advanced an average 1,000 yards (910 m), the Australian 3rd Division advancing up to 1,900 yards (1,700 m).[79][80]

After the British attacking units reached their final positions, their artillery fired an interdiction barrage for an additional two and a half hours, allowing the troops to consolidate.[81] The British captured 5,000 prisoners during the battle.[82] The British high command concluded that the number of enemy casualties meant that resistance was faltering and resolved to make another attack immediately, although suggestions for a further advance that day were rejected. In his memoirs, Ludendorff wrote, 'The battle on the 4 October was extraordinarily severe and again we only came through it with enormous losses. (My War Memories 1914–1918, p. 490.). Foot Guard Regt No. 5 described it as the worst day yet experienced in the war. (OH 1917II p. 316, fn 1.).

Battle of Poelcappelle: 9 October

An advance on 9 October by over 10 divisions of the French First Army and British 2nd and 5th Armies at Poelkapelle (or Poelcappelle to the British) was a dismal failure for the Allies, with only minor advances by exhausted troops at a cost of 13,000 casualties.

First Battle of Passchendaele: 12 October

The First Battle of Passchendaele, on 12 October 1917 began with a further Allied attempt by 5 British and 3 ANZAC divisions (the New Zealand Division and the Australian 3rd and 4th Divisions) to gain ground around Poelcappelle. The heavy rain again made movement difficult and artillery could not be brought closer to the front owing to the mud. The Allied troops were fought-out, and morale was suffering. Against the well-prepared German defences, the gains were minimal and there were 13,000 Allied casualties.

On this day there were more than 2,700 New Zealand casualties, of which 45 officers and 800 men were either dead or lying mortally wounded between the lines. In terms of lives lost in a day, this remains the blackest day in New Zealand’s recorded history.

Second Battle of Passchendaele: 26 October – 10 November

The four divisions of the Canadian Corps were transferred to the Ypres Salient and to make additional advances on Passchendaele.[83] The Canadian Corps relieved II Anzac Corps on 18 October from their positions along the valley between Gravenstafel Ridge and the heights at Passchendaele.[84] The front line was mostly the same as the one occupied by the 1st Canadian Division in April 1915.[84] The Canadian Corps operation was to be executed in a series of three attacks each with limited objectives, delivered at intervals of three or more days. As the Canadian Corps position was directly south of the inter-army boundary between the British Fifth and Second Armies, the British Fifth Army would mount subsidiary operations on the Canadian Corps' left flank while the I Anzac Corps would advance to protect the right flank.[85] The execution dates of the phases were tentatively given as 26 October, 30 October and 6 November.[85]

The British Fifth Army undertook two minor operations on the 22 October, one with the French First Army at Houthulst Forest, the other east of Poelcappelle.[86] The objective of the attack was to maintain pressure on the Germans while the Canadians Corps prepared for their assault, as well as supporting the French attack on Malmaison.[83][87][Note 5] The attack commenced at 5:35 am, with the French 1st Division and the British 35th Division attacking towards the Houthulst Forest and the British 34th and 18th Divisions attacking from Poelcappelle.[89] The French 1st Division successfully covered the left flank of the attack towards the Houthulst Forest, while the British 35th Division initially managed to seize its first objectives but was forced back to its starting line by German counter-attacks.[90] The left flank of the attack by the British 34th Division was unsuccessful, while the right flank managed to keep up with the attacking forces of the British 18th Division.[90]

The first stage began on the morning of 26 October.[91] The 3rd Canadian Division was assigned the northern flank which included the sharply rising ground of the Bellevue spur. South of the Ravebeek creek, the 4th Canadian Division would take the Decline Copse which straddled the Ypres-Roulers railway.[92] The 3rd Canadian Division captured the Wolf Copse and secured its objective line but was ultimately forced to drop a defensive flank to link up with the flanking division of the British Fifth Army. The 4th Canadian Division initially captured all its objectives but gradually retreated from the Decline Copse due to German counter-attacks and mis-communications between the Canadian and Australian units to the south.[93]

The second stage began on 30 October and was intended to capture the position not captured during the previous stage and gain a base for the final assault on Passchendaele.[93] The southern flank was to capture the strongly held Crest Farm while the northern flank was to capture the hamlet of Meetcheele as well as the Goudberg area near the Canadian Corps' northern boundary.[94] The southern flank quickly captured Crest Farm and begun sending patrols beyond its objective line and into Passchendaele. The northern flank was again met with exceptional German resistance. The 3rd Canadian Division captured Vapour Farm at the corps' boundary, Furst Farm to the west of Meetcheele and the crossroads at Meetcheele but remained short of its objective line.[94]

To permit time for inter-divisional relief, there was a seven day pause between the second and third stages. The British Second Army was ordered to take over a section of the British Fifth Army front adjoining the Canadian Corps so that the central portion of the assault could proceed under a single command.[95] Three consecutive rainless days between 3 and 5 November aided logistical preparations and reorganization of the troops for the next stage.[96] The third stage began on the morning of 6 November with the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions having taken over the front, relieving the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions respectively. Less than three hours after the start of the assault, many units had reached their final objective lines and the village of Passchendaele had been captured. The Canadian Corps launched a final action on 10 November to gain control of the remaining high ground north of the village, in the vicinity of Hill 52.[97] This attack on 10 November brought to an end the long drawn-out battle.[98]

Aftermath

On 24 October, The Austro-German 14th Army, under General der Infanterie Otto von Below, achieved a significant victory against the Italian Army at the Battle of Caporetto. In fear that Italy might be put out of the war, the French and British Governments each promised to send six divisions to the Italian Front.[99] All troops were rapidly and efficiently transferred between 10 November and 12 December, due to good administrative preparations made by Ferdinand Foch, who had been sent to Italy in April 1917 to plan for just such an emergency, and who was now French Chief of Staff.[100] The decrease in resources forced Haig to conclude the offensive, much to his dissatisfaction, just short of Westrozebeke.[101] To the south, the British Third Army collected sufficient resources over the preceding months to permit the execution of a surprise attack near Cambrai.[102] The Battle of Cambrai began on 20 November and the British initially breached the German Hindenburg Line in the first successful use of tanks in a combined arms operation.[103] The German Operation Michael began on 21 March 1918 and the supporting Battle of the Lys on 9 April. In the space of three days, the Germans quickly regained almost all of the ground taken by the Allies during the Battle of Passchendaele. The Germans were easily pushed away from Ypres once more in the fifth and final battle around the city in September and October 1918.

Casualties

Casualty figures are in dispute. In the British Official History, Brigadier-General James E. Edmonds puts British losses at 244,897 and estimates German losses at 400,000. C.R.M.F Cruttwell in A History of the Great War, 1914–1918 states British casualties at 300,000 and German losses at 400,000. In his book Haig, John Terraine puts British losses at the same level, but disputes German losses were that high [400,000]. In Road to Paschendaele, Terraine, after further research, concluded German casualties to be 260,400. Prior and Wilson in Passchendaele give German losses as 275,000 and British casualties just under 200,000.

Leon Wolff, a critic of Haig, claimed German casualties were 270,710 and British 448,614, but the latter figure was refuted by Terraine, who pointed out that despite stating that this was the total figure for the second half of 1917, Wolff had neglected either to deduct the 75,681 British casualties for Cambrai given in the Official Statistics from which he was quoting, or to make any deduction for "normal wastage" - casualties averaging 35,000 per month suffered in periods when there was no major offensive, eg. the first thirty days of July or the latter part of December[104].

A. J. P. Taylor in The First World War, states German losses to be 200,000 and British losses to be 300,000. He writes that British official history performed a "conjuring trick" on these figures and claimed that German losses were 400,000 and British losses 250,000, adding that no one believes these "farcical calculations".[105] Two poets, Irishman Francis Ledwidge, 25, of 1st Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, in 29th Division, and Hedd Wyn, a Welsh-language poet serving with the Royal Welch Fusiliers at Pilckem Ridge, were both killed in action on 31 July.

Adolf Hitler fought in the Battle of Passchendaele as a member of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division and was injured on the night of 13 October 1918, when he was caught in a British gas attack on a hill south of Werwick.[106]

Commemoration

The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing commemorates those of all Commonwealth nations, except New Zealand, who died in the Ypres Salient and have no known grave. In the case of the United Kingdom only casualties before 16 August 1917 are commemorated on the memorial. United Kingdom and New Zealand servicemen who died after that date are named on the memorial at Tyne Cot Cemetery. There are of course numerous tributes and memorials all over Australia and New Zealand to ANZAC soldiers who died in the battle, including plaques at the Christchurch and Dunedin railway stations.[107] For the Canadian Corps, participation in the Second Battle of Passchendaele is commemorated with the Passchendaele Memorial located at the former site of the Crest Farm on the southwest fringe of Passchendaele village.[108]

One of the newest memorials to be dedicated to the fighting contribution of a group is the Celtic Cross memorial commemorating the Scottish contribution and efforts to the fighting in Flanders during the Great War. The memorial is located on the Frezenberg Ridge where the Scottish 9th and 15th Divisions, as part of the British Army, fought during the Battle of Passchendaele. The monument was dedicated by the Scottish Parliament's Minister for Europe Linda Fabiani during the late summer of 2007, the 90th anniversary of the battle.

Notes

- ^ Battle of Passchendaele is perhaps the most common name for the campaign in English, but is not universally used. Third Battle of Ypres' was the name adopted by the British Official History of the First World War. The German history uses the term Third Flanders Battle (Template:Lang-de), while the French term is Second Battle of Flanders (Template:Lang-fr)

- ^ Entente forces included British, Canadian, South African, French and ANZAC units

- ^ 'High ground' is a relative term. Passchendaele itself is on a ridge about 70ft (25m) above the surrounding plains. The Gheluvelt Plateau is about 100ft (35m) above surrounding area. Wytschaete is about 150ft (50m) above the ground before it. Even so, these terrain features were very important for artillery observation.[19]

- ^ For instance, Haig's biographer Brig. John Charteris, who was also his Intelligence Officer, says that "Careful investigation of the records of 80 years showed that in Flanders the weather broke early with the regularity of the Indian monsoon". Lt Col Ernest Gold, the BEF's meteorological expert at the time, later went on record to contradict him, saying "It is quite contrary to the evidence of the records which show that the weather in August 1917 was exceptionally bad...". Historians nonetheless differ on whether the weather of Flanders in 1917 was typical or not. For instance, Winter takes the view that Haig had conclusive evidence that should have led him to expect heavy rainfall and hence mud. Steel and Hart by contrast take the view that Haig was unlucky.[31][32][33]

- ^ The attack consisted of units from XVIII Corps (18th Division) and XIV Corps (34th and 35th Divisions), as well as units from the French I Corp (1st Division).[88]

Footnotes

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 211–212.

- ^ Travers, The Killing Ground pp. 215–7.

- ^ Terraine pp. 336–342.

- ^ Travers, The Killing Ground, p. xxi.

- ^ Terraine pp. 342–347.

- ^ "WWI veteran Patch dies aged 111". BBC News. 25 July 2009.

- ^ Terraine p. 14.

- ^ Terraine p. 15.

- ^ Winter, Haig's Command, p. 78.

- ^ Hart & Steel p. 28.

- ^ Hart & Steel p. 30.

- ^ Terraine pp. 28–29.

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 31–32.

- ^ Winter, Haig's Command, p. 73.

- ^ Terraine p. 29.

- ^ Terraine pp. 24–25.

- ^ Prior & Wilson, pp. 29, 3 (paperback edition).

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 18–19.

- ^ Terraine p. 2.

- ^ Hart & Steel p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Hart & Steel p. 29.

- ^ Terraine pp. 3, 17–24.

- ^ Terraine p. 32.

- ^ Winter, Haig's Command, p. 88.

- ^ Terraine p. 336.

- ^ Sheldon p. xi.

- ^ Sheldon p. x.

- ^ Terraine p. 21.

- ^ Winter, Haig's Command, p. 92.

- ^ Terraine p. 206.

- ^ Winter, pp. 91–2.

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 140–141.

- ^ Terraine pp. 205–206.

- ^ Prior and Wilson, p. 45–7.

- ^ Keegan pp. 348–349.

- ^ Terraine pp. 87–89.

- ^ Hart & Steel p. 36.

- ^ a b Sheldon p. 1.

- ^ Terraine p. 118

- ^ a b Hart & Steel pp. 42–43.

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Hart & Steel p. 44.

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 41, 44.

- ^ Sheldon p. 23.

- ^ Hart & Steel pp. 50–54.

- ^ a b Terraine p. 120.

- ^ a b Hart & Steel p. 55.

- ^ Sheldon p. 28.

- ^ Hart & Steel p. 56.

- ^ Sheldon pp. 28–29.

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 70–1 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and wilson, pp. 74–5 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 72, 75 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 76–7 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 79–82 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, p. 83 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, p. 80 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, p. 86 (pb edition).

- ^ Prior and Wilson, p. 89.

- ^ a b Prior and Wilson, p. 90.

- ^ Prior & Wilson, p. 92.

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 90–1.

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 92–3.

- ^ Prior and Wilson, pp. 94–5.

- ^ a b Nicholson p. 308.

- ^ Edmonds p. 237.

- ^ a b c d e Malkasian p. 41.

- ^ a b Edmonds p. 238.

- ^ a b c d Edmonds p. 239.

- ^ Leach p. 76.

- ^ Cook p. 149.

- ^ a b Robbins p. 128.

- ^ a b Bean p. 837.

- ^ Prior & Wilson p. 133.

- ^ Groom p. 207.

- ^ Prior & Wilson p. 135.

- ^ Malkasian p. 42.

- ^ Bean p. 847.

- ^ Carlyon p. 485.

- ^ Pedersen p. 257.

- ^ Bean p. 866.

- ^ Groom p. 208.

- ^ a b Bean 929

- ^ a b Nicholson p. 312.

- ^ a b Nicholson p. 314

- ^ Bean p. 930.

- ^ Edmonds p. 347.

- ^ Edmonds p. 348.

- ^ Evans p. 133.

- ^ a b Evans p. 134.

- ^ Wolff p. 246.

- ^ Nicholson p. 318.

- ^ a b Nicholson p. 320.

- ^ a b Nicholson p. 321.

- ^ Nicholson p. 323.

- ^ "The Ypres Salient". Second Passchendaele. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. n.d. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ Nicholson p. 325.

- ^ "Canada and the Battle of Passchendaele". Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007.

- ^ Bean pp. 935–936.

- ^ Nicholson p. 331.

- ^ Bean p. 936.

- ^ Harris pp. 107, 111.

- ^ Harris pp. 124–125.

- ^ Terraine pp. 344-5.

- ^ Taylor 1972.

- ^ William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, (Simon & Schuster, 1960), p. 30.

- ^ New Zealand History.

- ^ Vance p. 66.

References

- Bean, C.E.W. (1941). The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918: Volume IV: The A.I.F. in France 1917 (11th ed.). Sydney: Halstead Press Pty Limited.

- Carlyon. MISSING CITATION.

- Cook, Tim (2000). No Place to Run: The Canadian Corps and Gas Warfare in the First World War. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0774807407.

- Edmonds, James (1948). France and Belgium 1917. Vol II. 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). London: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press.

- Evans, Martin Marix (2005). Passchendaele: The Hollow Victory. London: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 1844153681.

- Groom, Winston (2002). A Storm in Flanders: The Ypres Salient, 1914–1918 Tragedy and Triumph on the Western Front. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-842-5.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, ideas, and tanks: British military thought and armoured forces, 1903–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-790-3762-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Hart, Peter; Steel, Nigel (2001). Passchendaele: the Sacrificial Ground. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 0304359750.

- Keegan, John (1998). The First World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6645-1.

- Leach, Norman (2009). "'Passchendaele – Canada's Other Vimy Ridge". Canadian Military Journal. 9 (2). Department of National Defence: 73–82.

- Malkasian, Carter (2002). A history of modern wars of attrition. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 0275973794.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L. (1962). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary.

- Pedersen. MISSING CITATION.

- Prior, Robin; Wilson, Trevor (1998). Passchendaele: The Untold Story. Cumberland: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300072279.

- Robbins, Simon (2005). British generalship on the Western Front 1914–18: Defeat into Victory. Abingdon: Frank Cass. ISBN 0415350069.

- Sheldon, Jack (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 1844155641.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1972). The First World War. An Illustrated History. New York: Perigee Trade.

{{cite book}}: Text "ISBN-10: 0399502602" ignored (help) - Terraine, John (1984). The Road to Passchendaele: The Flanders Offensive 1917, A Study in Inevitability. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-436-51732-9.

- Travers, Tim (2003). The Killing Ground: The British Army, the Western Front & the Emergence of Modern War 1900–1918. London: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 0-85052-964-9.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Wolff, Leon (1958). In Flanders Fields: The 1917 Campaign. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780140146622.

External links

- [1] Passchendaele – The Final Call – Poem and biography of Captain James Willard

- Passchendaele Original reports from The Times

- Battles: The Third Battle of Ypres, 1917

- Westhoek The great war in Flanders Fields – A war and peace experience.

- Second Lieutenant Robert Riddel, Military Cross, 10th Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, Passchendaele, 12 October 1917

- Guernsey students re-trace a soldier's journey to Passchendaele for Radiowaves (2007)

- Robert Hall "Uncovering the secrets of Ypres" 23 February 2007. BBC News, Belgium

- The Battle of Passchendaele Day by day detailed description of battle (with maps).

- Use dmy dates from May 2011

- Battles of World War I involving Australia

- Battles of World War I involving Canada

- Battles of World War I involving France

- Battles of World War I involving Germany

- Battles of World War I involving New Zealand

- Battles of World War I involving South Africa

- Battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom

- Battles of the Western Front (World War I)

- Conflicts in 1917

- Ypres

- Passchendaele

- 1917 in Belgium