Battle of Ilipa

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

| Battle of Ilipa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Roman Republic | Carthage | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Publius Cornelius Scipio Lucius Marcius Septimus Marcus Junius Silanus |

Hasdrubal Gisco Mago Barca | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total: 48,000–55,000 Polybius: 48,000 men • 45,000 infantry • 3,000 cavalry Livy: 55,000 men |

Total: 54,500–74,000 Polybius: 74,000 men • 70,000 infantry • 4,000 cavalry 32 war elephants Livy: 54,500 men • 50,000 infantry • 4,500 cavalry Unknown number of elephants Modern estimate:[1] 64,000 men • 60,000 infantry • 4,000 cavalry 32 elephants | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 7,000 killed |

More than 48,500 killed or captured

| ||||||||

Location within Spain | |||||||||

The Battle of Ilipa (/ˈɪlɪpə/) was an engagement considered by many as Scipio Africanus’s most brilliant victory in his military career during the Second Punic War in 206 BC. It may have taken place on a plain east of Alcalá del Río, Seville, Spain, near the village of Esquivel, the site of the Carthaginian camp.[2]

Though it may not seem to be as original as Hannibal’s tactic at Cannae, Scipio's pre-battle maneuver and his reverse Cannae formation stands as the acme of his tactical ability, in which he forever broke the Carthaginian hold in Iberia, thus denying any further land invasion into Italy and cutting off a rich base for the Barca dynasty both in silver and manpower.

Prelude

[edit]After the Carthaginian defeat at the Battle of Baecula and Hasdrubal Barca's (Hannibal’s brother) departure for Italy, new reinforcements were sent to Iberia from Carthage at the beginning of 207 BC under the command of Hanno, who joined Mago Barca (Hannibal's younger brother).[3] The troops were bolstered by recruitment among the Celtiberians. Additionally, Hasdrubal Gisco advanced his army from Gades (modern-day Cadiz) in Andalusia.[4] Facing such a powerful enemy force, Scipio decided to send a detachment under the command of Marcus Junius Silanus to defeat Mago first; Mago’s camp was attacked by surprise by the Roman troops and scattered. Hanno himself was captured.[5] This left Hasdrubal to face Scipio’s forces alone. The Carthaginian, however, managed to avoid a direct confrontation by stationing his forces in various fortified Iberian cities. Thus, the 207 BC campaign concluded without further significant actions.[6]

In 206 BC, the two Carthaginian commanders, Hasdrubal, son of Gisco, and Mago Barca, Hannibal’s youngest brother, still reeling from a series of defeats by the Romans, reached Ilipa, near present-day Seville, to join their Iberian and Numidian allies. They assembled an army of approximately 70,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 32 elephants.[7] Scipio gathered his Roman and allied Iberian forces, fielding an army of 45,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. After several days of skirmishes, Scipio surprised the opposing army, decisively defeating it. Hasdrubal and Mago managed to escape and took refuge in Gades.[8]

Battle

[edit]

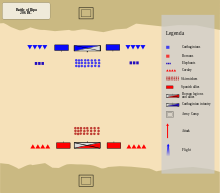

In the spring, the Carthaginians launched an offensive in an attempt to reestablish their dominance over the Iberian Peninsula.[9] Mago was joined at Ilipa by Hasdrubal Gisco, and together they assembled an army larger than that of the Romans.[10] Mago boldly attacked the Roman camp with the majority of his cavalry, comprising King Massinissa’s Numidian horsemen. However, the assault was thwarted by the Roman cavalry, which charged the flank of the enemy, inflicting significant losses.[11] In the following days, the generals chose to face and observe each other without engaging in full battle. Each day, both armies lined up on the field in the same formation: Scipio placed the legionaries in the center with Iberians on the flanks, backed by cavalry, and stationed the Velites in front of the legionaries, as usual. Meanwhile, the Carthaginians mirrored the Roman formation, positioning elite African infantry in the center (intended to confront the Roman legionaries), with Iberians and cavalry on the flanks (who would face their Roman counterparts), and light infantry in the center front, positioned before the Africans, with elephants at the forefront of the cavalry.[12]

This continued for several days until Scipio decided to take the initiative and attack the enemy: he prepared his troops overnight, and at dawn, he sent the Velites and cavalry to raid the enemy camp.[13] The Carthaginian army emerged on the battlefield in complete disorder, as their soldiers had been caught off guard and were unprepared to fight (many were still asleep). Hasdrubal and Mago positioned their troops as in previous days, but this repetition proved costly. Scipio, in fact, had changed his formation, placing the legionaries on the flanks and the allied Iberians in the center. The Velites were maneuvered along the line, positioned between the legionaries and cavalry, tasked with handling the enemy’s elephants.[14] The two armies finally engaged, with clashes between the cavalries, Roman legionaries fighting the Iberians in the Carthaginian forces, and the Velites confronting the elephants. However, as predicted by the young Scipio, the central forces of the two armies did not engage directly. The Roman proconsul had deliberately pulled back his Iberian allies. The skill of the legionaries allowed them to overcome Hasdrubal and Mago’s soldiers, while the Velites used javelins and trumpets to drive the elephants into a frenzy, causing them to trample much of the Carthaginian cavalry.[15]

As a result, the African soldiers, unable to assist their comrades (as doing so would have left the center completely exposed, effectively dividing their formation and allowing Scipio’s Iberians to outflank and attack them from the sides and rear), grew demoralized.[16] The rest of the Carthaginian army, seeing that even their best troops had lost hope, began to flee with them in an initially orderly retreat. However, when the Roman general ordered his Iberian soldiers to pursue the enemies, their retreat turned into a full rout. The Carthaginian army was virtually annihilated, and the few survivors surrendered shortly after. Hasdrubal and Mago managed to escape and took refuge in Gades.[17]

After-battle maneuvers

[edit]Although temporarily safe in their camp, the Carthaginians were not able to rest. Facing the inevitable Roman attack the next morning, they were obliged to strengthen their defenses. But, as more and more Iberian mercenaries deserted the Carthaginians as night drew forward, Hasdrubal tried to slip away with his remaining men in darkness.

Scipio immediately ordered a pursuit. Led by the cavalry, the whole Roman army was hot on Hasdrubal's tail. When the Romans finally caught up with the Carthaginian host, the butchery began. Hasdrubal was left with only 6,000 men, who then fled to a mountain top without any water supply. This remnant of the Carthaginian army surrendered a short time later, but not before Hasdrubal and Mago had made their escape.

Aftermath

[edit]After the battle, Hasdrubal Gisco departed for Africa to visit the powerful Numidian king Syphax, in whose court he was met by Scipio, who was also courting the favor of the Numidians.

Mago Barca fled to the Balearics, whence he would sail to Liguria and attempt an invasion of northern Italy. After the conquest of Carthaginian Iberia, Scipio returned to Rome. He was elected consul in 205 BC with a near-unanimous nomination, and after receiving the Senate's consent, he would have the control of Sicily as proconsul, from where his invasion of the Carthaginian homeland would be realized.

References

[edit]- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2008). Scipio Africanus: Rome's Greatest General. Potomac Books. pp. 118, 262. ISBN 978-1-59797-205-5.

- ^ O'Connell, Kevin P. "The Search for the Battle-site of Ilipa: Back to Basics". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ^ Daly, Gregory (2005-08-18). "Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War". doi:10.4324/9780203987506.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Reforms for more and better quality jobs in Spain", OECD Economic Surveys: Spain, OECD, pp. 61–97, 2017-03-14, ISBN 978-92-64-27184-5, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ "The Roman Economy", Roman Iberia : Economy, Society and Culture, Duckworth, ISBN 978-0-7156-3499-8, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Davis, Paul K (2001-06-14), "Lechfeld 9August 955", 100 Decisive Battles, Oxford University PressNew York, NY, pp. 110–112, ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Lentzsch, Simon (2023), "The Darkest Hour: The Roman-Carthaginian Wars", Roma Victa, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 185–380, ISBN 978-3-476-05941-3, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ "Epilogue", Art in the Roman Empire, Routledge, pp. 136–139, 2013-04-15, ISBN 978-0-203-71411-9, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Daly, Gregory (2005-08-18). "Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War". doi:10.4324/9780203987506.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jones, J. (1999-10-23). "Antismoking campaigns should "target 4 year olds"". BMJ. 319 (7217): 1090–1090. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7217.1090b. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1255897.

- ^ "Roman cavalry mounts", The Roman Cavalry, Routledge, pp. 179–196, 2013-01-11, ISBN 978-0-203-06016-2, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Cartledge, Paul (2013-06-09), "Hoplitai/Politai: Refighting Ancient Battles", Men of Bronze, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14301-9, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Bloomfield, Maxwell (February 2000). Jones, Scipio Africanus (1863-1943), lawyer. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Rawlings, Louis (2010-01-01), "8. The Carthaginian Navy: Questions And Assumptions", New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, BRILL, pp. 253–287, ISBN 978-90-04-18734-4, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ "Pagan Basilicas", Art in the Roman Empire, Routledge, pp. 85–92, 2013-04-15, ISBN 978-0-203-71411-9, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Fuhrer, Therese (2018-04-19). "Carthage—Rome—Milan". Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198768098.003.0009.

- ^ "Ilipa". Der Neue Pauly. Retrieved 2024-11-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adrian Goldsworthy; In the Name of Rome - The Men Who Won the Roman Empire; 2003; ISBN 0-297-84666-3

- B.H. Liddell Hart; Scipio Africanus: greater than Napoleon; 1926; ISBN 0-306-80583-9

- Nigel Bagnall; The Punic Wars; 1990; ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Polybius; The Rise of the Roman Empire; Trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert; 1979; ISBN 0-14-044362-2

- Serge Lancel; Hannibal; Trans. Antonia Nevill; 2000; ISBN 0-631-21848-3

- Santiago Posteguillo; Las Legiones Malditas; 2008; ISBN 978-84-666-3768-8