Common wombat

| Common wombat[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vombatus ursinus ursinus, Maria Island, Tasmania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Vombatidae |

| Genus: | Vombatus |

| Species: | V. ursinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vombatus ursinus (Shaw, 1800)

| |

| |

| Common wombat range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Reference[3]

| |

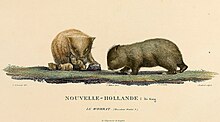

The common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), also known as the bare-nosed wombat, is a marsupial, one of three extant species of wombats and the only one in the genus Vombatus. It has three subspecies: Vombatus ursinus hirsutus, found on the Australian mainland; Vombatus ursinus tasmaniensis (Tasmanian wombat), found in Tasmania; and Vombatus ursinus ursinus (Bass Strait wombat), found on Flinders Island and Maria Island in the Bass Strait.

The mainland species is the largest of the three, with its largest specimens measuring up to 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) and 35 kg (77 lb). The common wombat is herbivorous, mainly nocturnal, and lives in burrows. Being a marsupial, its joeys inhabit a pouch on the mother for around five months after birth.

Taxonomy

[edit]

The common wombat was first described by George Shaw in 1800.[citation needed]

There are three extant subspecies of the common wombat, confirmed in 2019:[4]

- Bass Strait (common) wombat, also written "Common Wombat (Bass Strait)"[5] or "Bass Strait wombat"[6] (V. u. ursinus), the nominate form, was once found throughout the Bass Strait Islands, but is now restricted to Flinders Island to the north of Tasmania, and to Maria Island to the east of Tasmania where it was introduced. Its population was estimated at 74,000 in 2023.[7][8]

- Hirsute wombat (V. u. hirsutus) is found on the Australian mainland.[9][8]

- Tasmanian wombat (V. u. tasmaniensis) is found in Tasmania.[9][10] It is smaller than V. u. hirsutus.[11] Its population was estimated at 840,000 in 2023.[7][8]

Hackett's wombat (V. hacketti) is an extinct species of genus Vombatus, inhabiting the southwestern part of Australia.[12][13][14][15] Being around the same size as V. ursinus, with an average weight of 30 kg, V. hacketti went extinct at the end of the Late Pleistocene, in the Quaternary extinction event.[16][17]

Description

[edit]Common wombats are sturdy and built close to the ground. They have small ears and eyes, and a large bald nose. Their fur is thick and coarse and its colour varies from light brown to grey and black. The Flinders Island wombat is the smallest of the three subspecies at around 75 cm (30 in) in length, while the Tasmanian wombat averages 85 cm (33 in) and a weight of 20 kg (44 lb). The largest of the three, the mainland species, are around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long and weigh 27 kg (60 lb) on average. Larger specimens can reach 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) and 35 kg (77 lb).[8]

They have short, strong legs with long claws and are very efficient diggers. One mark of distinction from all other marsupials is that the wombat has a single pair of upper and lower incisors, which never stop growing.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Common wombats are widespread in the cooler and better-watered parts of southern and eastern Australia, including Tasmania and Victoria, and in mountain districts as far north as southern Queensland.[18][19] In Tasmania, their preference is heathland, coastal scrub, and open forest.[8]

Common wombats can be found at any elevation in the south of their range, but in the north of their range are only found in higher, more mountainous areas. They may be found in a variety of habitats including rainforest, eucalyptus forest, woodland, alpine grassland, and coastal areas.[20] In some regions, they have adapted to farmland and can even be seen grazing in open fields with cattle and sheep.

Behaviour

[edit]Common wombats have been described as ecological engineers,[21] as their burrow building results in soil turnover and aeration, which assists plant growth, and provides habitat for a range of invertebrate and vertebrate species.[22][23]

Common wombats are a solitary, territorial species, with each wombat having an established range in which it lives and feeds.[24] In this area, they dig a tunnel system, with tunnels ranging from 2–20 m (6 ft 7 in – 65 ft 7 in) in length, along with many side tunnels, and often more than one entrance. More than one wombat may build their nest, made from sticks, leaves, and grasses, in one burrow.[8]

A wide range of other animals are known to make use of wombat burrows including reptiles, rodents, rabbits, echidnas, wallabies, birds and koalas. Wombats are usually fairly tolerant of non-threatening species, and have a number of burrows that they can occupy.[25][26] The typically switch the burrow that they sleep in every 1-9 days.[27]

Many wombats can live in the same burrow, and wombats normally live in the same burrow for their whole lifespan unless the wombat is forced out of the burrow by farmers or other animal species, or unless the burrow is destroyed. Often nocturnal, the common wombat does come out during the day in cooler weather, such as in early morning or late afternoon.[28]

Diet

[edit]

Common wombats are herbivorous,[29][30] subsisting on grass, snow tussocks, and other plant materials. Foraging is usually done during the night. They are the only marsupial in the world whose teeth constantly grow. Due to the underlying enamel structure of the teeth, the continuously growing teeth maintain a self-sharpening ridge[31] which allows easier grazing of the diet consisting of mainly native grasses.[28] Captive wombats are also fed a range of vegetables.[32]

Breeding

[edit]The common wombat breeds mainly in winter.[8] It can breed every two years and produce a single joey. Wombats appear to mate side-ways[33] The gestation period is about 20–30 days, and the young remain in the pouch for five months. When leaving the pouch, they weigh between 3.5 and 6.5 kg (7.7 and 14.3 lb). The joey is weaned around 12 to 15 months of age, and is usually independent at 18 months of age.[28] Wombats have an average lifespan of 15 years in the wild and 20 years in captivity.

-

female with joey

-

outside burrow

-

Joey on Maria Island

Threats

[edit]Whilst bare-nosed wombats are listed as Least Concern by the IUCN,[2] they remain threatened largely due to anthropomorphic factors[34] including habitat reduction, roadkill[35] and sarcoptic mange.[36] Sarcoptic mange is prevalent in the population[37][38] and remains the most problematic of issues facing bare-nosed wombats, with wildlife carers regularly treating wombats in the field[36][39] with low-risk moxidectin.[40]

Wombats have also been reported to harbour a range of parasites, including ticks and associated pathogens.[41][42]

Its main predators are Tasmanian devils and eagles.[8]

There was a significant increase in overall wombat counts throughout Tasmania between 1985 and 2019 although numbers decreased in the last 10 years of that period in the west Tamar area.[8]

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Genus Vombatus ursinus". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Taggart, D.; Martin, R.; Menkhorst, P. (2016). "Vombatus ursinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T40556A21958985. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T40556A21958985.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ S. Jackson; C. Groves (2015). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. p. 101.

- ^ a b Howarth, Carla (13 April 2019). "Scientists discover wombats on Tasmania's islands are one of three genetically unique subspecies". ABC News. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Vombatus ursinus ursinus — Common Wombat (Bass Strait)". Species Profile and Threats Database. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian Government. 7 July 2022.

Text may have been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY 3.0 AU) licence.

Text may have been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY 3.0 AU) licence.

- ^ "Bass Strait Wombat". Threatened Species Link. 6 June 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ a b Knoblauch, Wiebke; Carver, Scott; Driessen, Michael M; Gales, Rosemary; Richards, Shane A (4 September 2023). "Abundance and population growth estimates for bare-nosed wombats". Ecology and Evolution. 13 (9): e10465. doi:10.1002/ece3.10465. PMC 10477484. PMID 37674647.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Common Wombat". Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania. 3 April 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Common Wombat". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ Spencer, Walter Baldwin; Kershaw, James A. (1910). The existing species of the genus Phascolomys. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne. Vol. 3. Melbourne: J. Kemp, government printer.

- ^ "Common Wombat". Wombania's Wombat Information Center. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ "Megafauna". austhrutime.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Triggs, Barbara (1 January 2009). Wombats. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 9780643096011.

- ^ "Anaspides.net". www.anaspides.net. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Johnson (2002). "Determinants of loss of mammal species during the Late Quaternary 'megafauna' extinctions: life history and ecology, but not body size". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269 (1506): 2221–2227. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2130. PMC 1691151. PMID 12427315.

- ^ "The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database cubit: The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database Extinct Mammals: Marsupials: Vombatus hacketti". cubits.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ MacPhee, R. D. E. (30 June 1999). Extinctions in Near Time. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780306460920.

- ^ Thorley RK, Old JM (2020). Distribution, abundance and threats to bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus). Australian Mammalogy. 42, 249-256. DOI: 10.1071/AM19035

- ^ "Bare-nosed wombat Vombatus ursinus" (PDF). Queensland Government. 16 September 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Thorley, Rowan K.; Old, Julie M. (2020). "Distribution, abundance and threats to bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Australian Mammalogy. 42 (3): 249. doi:10.1071/AM19035. S2CID 213536628.

- ^ Old, Julie M.; Lin, Simon H.; Franklin, Michael J. M. (December 2019). "Mapping out bare-nosed wombat (Vombatus ursinus) burrows with the use of a drone". BMC Ecology. 19 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s12898-019-0257-5. PMC 6749681. PMID 31533684. S2CID 202641093.

- ^ Old, Julie M.; Hunter, NE; Wolfenden, J (2018). "Who utilises bare-nosed wombat burrows?". Australian Zoologist. 39 (3): 409–413. doi:10.7882/AZ.2018.006. S2CID 135128293.

- ^ Fleming, PA; Anderson, H; Prendergast, AS; Bretz, MR; Valentine, LE; Hardy, GES (1 April 2014). "Is the loss of Australian digging mammals contributing to a deterioration in ecosystem function?". Mammal Review. 44 (2): 94–108. doi:10.1111/mam.12014.

- ^ "Living with wombats". NSW Department of Planning and Environment. NSW Government. 17 February 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Australian bushfires: animals that take refuge in wombat burrows usually uninvited, experts say". AFP Fact Check. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Nimmo, Dale (15 January 2020). "Viral stories of wombats sheltering other wildlife from the bushfires aren't entirely true". ABC News. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Carver, Scott; Stannard, Georgia L; Martin, Alynn M (6 September 2023). "The Distinctive Biology and Characteristics of the Bare-Nosed Wombat (Vombatus ursinus)". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 12 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-021022-042133.

- ^ a b c "Wombats, Wombat Pictures, Wombat Facts". National Geographic Society. 11 April 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Old, Julie M.; Vallin, Blaire L.; Thorley, Rowan K.; Casey, Fiona; Stannard, Hayley J. (2024). "DNA metabarcoding analysis of the bare-nosed wombat (Vombatus ursinus) diet". Ecology and Evolution. 14 (5): e11432. doi:10.1002/ece3.11432. PMC 11103767. PMID 38770127.

- ^ Casey, Fiona; Vallin, Blaire L.; Wolfenden, Jack; Old, Julie M.; Stannard, Hayley J. (2024). "Nutritional composition of plants and preliminary assessment of nutrition in free-ranging bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Australian Mammalogy. 46 (2). doi:10.1071/AM23013.

- ^ Ferreira, J. M.; Phakey, P. P.; Palamara, J.; Rachinger, W. A.; Orams, H. J. (1989). "Electron microscopic investigation relating the occlusal morphology to the underlying enamel structure of molar teeth of the wombat (Vombatus ursinus)". Journal of Morphology. 200 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052000204. PMID 29865656. S2CID 46929011.

- ^ Stannard, Hayley J.; Purdy, Katherine; Old, Julie M. (2021). "A survey and critical review of wombat diets in captivity". Australian Mammalogy. 43 (1): 66. doi:10.1071/AM20028. S2CID 225365567.

- ^ Stannard, Hayley; Old, Julie (28 March 2023). "A rare video of wombats having sex sideways offers a glimpse into the bizarre realm of animal reproduction". The Conversation.

- ^ Thorley, Rowan K.; Old, Julie M. (2020). "Distribution, abundance and threats to bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Australian Mammalogy. 42 (3): 249. doi:10.1071/AM19035. S2CID 213536628.

- ^ Mayadunnage, S.; Stannard, H. J.; West, P.; Old, J. M. (6 July 2022). "Identification of roadkill hotspots and the factors affecting wombat vehicle collisions using the citizen science tool, WomSAT". Australian Mammalogy. 45 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1071/AM22001.

- ^ a b Old, J. M.; Sengupta, C.; Narayan, E.; Wolfenden, J. (April 2018). "Sarcoptic mange in wombats-A review and future research directions". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 65 (2): 399–407. doi:10.1111/tbed.12770. PMID 29150905.

- ^ Stannard, Hayley J.; Wolfenden, Jack; Hermsen, Eden; Vallin, Blaire T.; Hunter, Nicole E.; Old, Julie M. (2021). "Incidence of sarcoptic mange in bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Australian Mammalogy. 43: 85. doi:10.1071/AM20001.

- ^ Mayadunnage, Sujatha; Stannard, Hayley J.; West, Peter; Old, Julie M. (2023). "Spatial and temporal patterns of sarcoptic mange in wombats using the citizen science tool, WomSAT". Integrative Zoology. 19 (3): 387–399. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12776. PMID 37865949.

- ^ Old, Julie M.; Skelton, Candice J. A.; Stannard, Hayley J. (March 2021). "The use of Cydectin® by wildlife carers to treat sarcoptic mange in free-ranging bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Parasitology Research. 120 (3): 1077–1090. doi:10.1007/s00436-020-07012-8. PMID 33438043. S2CID 231595549.

- ^ Schraven, Andrea L.; Stannard, Hayley J.; Old, Julie M. (April 2021). "A systematic review of moxidectin as a treatment for parasitic infections in mammalian species". Parasitology Research. 120 (4): 1167–1181. doi:10.1007/s00436-021-07092-0. PMID 33615411. S2CID 231989259.

- ^ Beard, Danielle; Stannard, Hayley J.; Old, Julie M. (February 2021). "Parasites of wombats (family Vombatidae), with a focus on ticks and tick-borne pathogens". Parasitology Research. 120 (2): 395–409. doi:10.1007/s00436-020-07036-0. PMID 33409643. S2CID 253981632.

- ^ Beard, Danielle; Stannard, Hayley J.; Old, Julie M. (December 2021). "Morphological identification of ticks and molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens from bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Parasites & Vectors. 14 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s13071-020-04565-6. PMC 7814742. PMID 33468211.