Basilica Ulpia

Reconstruction of the basilica | |

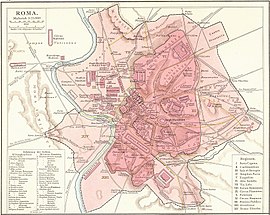

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Coordinates | 41°53′44.02″N 12°29′4.45″E / 41.8955611°N 12.4845694°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Basilica |

The Basilica Ulpia was an ancient Roman civic building located in the Forum of Trajan. The Basilica Ulpia separates the temple from the main courtyard in the Forum of Trajan with the Trajan's Column to the northwest.[1] It was named after Roman emperor Trajan whose full name was Marcus Ulpius Traianus.[2]

It became perhaps the most important basilica after two ancient ones, the Basilicas Aemilia and Julia. With its construction, much of the political life moved from the Roman Forum to the Forum of Trajan. It remained so until the construction of the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine.

Unlike later Christian basilicas, it had no known religious function; it was dedicated to the administration of justice,[3] commerce and the presence of the emperor. It was the largest in Rome measuring 117 by 55 meters (385 x 182 ft).[2]

Design and construction

[edit]The Basilica Ulpia was composed of a great central nave with four side aisles, two on each side of the nave. The short sides of the structure formed apses, while the main entrance was via three doorways on the long east front overlooking the Forum of Trajan, which was one meter below the level of the Basilica.[4] The columns and the walls were of precious marbles; the 50 meter (164 ft) high roof was covered by gilded bronze tiles.

The east façade featured a portico with three projecting porches. The center porch framed the main entrance and was the grandest, with 10 columns of yellow marble supporting it. Atop the center porch over an elaborate attic and entablature was a gilt bronze quadriga (four-horse chariot) escorted by Victories, with the two flanking porches topped by bigae (two-horse chariots).[4][5] Between the chariots were colossal statues of Trajan. The many rows of columns separating the side aisles are a traditional means of structure for basilicas. This method of structure can be traced back to Egyptian hypostyle Halls.[6] The Basilica Ulpia is very similar to one of the most famous hypostyle halls, Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak.

The apse at the northeast end of the Basilica is labelled Libertatis on a fragment of the Marble Plan of Rome, which suggests that it assumed the functions of the Atrium Libertatis, previously located in the Forum Romanum, the place where slaves were legally manumitted. As such there was likely a shrine to Libertas placed in the apse.[7]

Many of the columns still exist on site, although a large number have fallen. The whole of the construction was decorated with war spoils and trophies from the Dacian Wars conducted under the command of Trajan. The frieze above the entrance was inscribed with the names of the victorious legions involved in the Dacian campaign.[8]

Later, it was used as the architectural prototype by Constantine as the basis for the layout of the new Christian churches. The Basilica Ulpia was used as to model for Constantine completion of the Basilica of Maxentius.[9]

Excavations

[edit]

The Basilica Ulpia was first excavated by the occupying French government of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1813, after two convents on the site were demolished (Santo Spirito and di Santa Eufemia).[10] In 1814 Pope Pius VII returned from exile and resumed the excavations: it was under Pius that the grey granite columns were reassembled on their bases and walls built to delineate the excavation area. The excavations also uncovered the remains of the pavement made from rare marbles, which gradually disappeared over the course of the 19th century due to rapacious tourists.[10]

Clement VII removed several of the yellow giallo antico marble columns which once flanked the doorways of the structure to Saint Peter's Basilica, where they were erected in the transept, while one went to the Lateran Palace.[10]

Part of the foundation of the basilica continues today under the modern Via dei Fori Imperiali, a trunk road constructed during the rule of Benito Mussolini.

The reconstruction of the basilica, planned by former Rome Mayor Ignazio Marino in 2014, began in 2021. The work will be carried out by the method of anastilosis, in which the ruins are restored using the original architectural elements. The funds for the reconstruction in the amount of 1.5 million euros were donated by the Uzbek-Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tomlinson, R. A. From Mycenae to Constantinople: the Evolution of the Ancient City. London: Routledge, 1992. Print. ISBN 978-0-415-05998-5

- ^ a b Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-06-430158-9.

- ^ "Western architecture - Roman and early Christian".

- ^ a b "Basilica Ulpia". archive1.village.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-04-17. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 176.

- ^ The Forum of Trajan in Rome: A Study of the Monuments in Brief (2001) by James E. Packer; Roman Imperial Architecture (1981) by J. B. Ward-Perkins; Aulus Gellius: Attic Nights (1927) translated by John C. Rolfe (Loeb Classical Library).

- ^ Samuel B. Platner; Thomas Ashby (1929). "A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome". Oxford University Press. pp. 237–245.

- ^ Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome. Houghton Mifflin. p. 316.

- ^ Giavarini, Carlo., The Basilica of Maxentius: the Monument, its Materials , Construction, and Stability, Roma: L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2005.

- ^ a b c Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 314–315.

- ^ "the reconstruction in anastylosis starts". Italy24 News English. 2021-11-14. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

Further reading

[edit]- Lucentini, M. The Rome Guide. Interlink books.

External links

[edit]- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

![]() Media related to Basilica Ulpia (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Basilica Ulpia (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Basilica of Neptune |

Landmarks of Rome Basilica Ulpia |

Succeeded by Comitium |