Baseball card

A 1954 Bowman card of Mickey Mantle | |

| Company | Topps Panini |

|---|---|

| Country | United States Japan |

| Availability | c. 1860 [1]–present |

| Features | Baseball |

A baseball card is a type of trading card relating to baseball, usually printed on cardboard, silk, or plastic.[2] In the 1950s, they came with a stick of gum and a limited number of cards. These cards feature one or more baseball players, teams, stadiums, or celebrities.

Baseball cards are most often found in the Contiguous United States but are also common in Puerto Rico or countries such as Canada, Cuba, South Korea and Japan, where top-level leagues are present with a substantial fan base to support them. Some notable companies producing baseball cards include Topps and Panini Group.

Previous manufacturers include Fleer (now a brand name owned by Upper Deck), Bowman (now a brand name owned by Topps),[3] and Donruss (now a brand name owned by Panini).[4] Baseball card production peaked in the late 1980s and many collectors left the hobby disenchanted after the 1994-95 MLB strike.[5] However, baseball cards are still among the most sought collectibles of all time.

History

[edit]Pre-1900

[edit]

During the mid-19th century in the United States, baseball and photography gained popularity. As a result, baseball clubs began to pose for group and individual pictures, much like members of other clubs and associations posed. Some of these photographs were printed onto small cards similar to modern wallet photos. The oldest known surviving card shows the Brooklyn Atlantics from around 1860.[1][6]

As baseball increased in popularity and became a professional sport during the late 1860s, trade cards featuring baseball players appeared. These were used by various companies to promote their business, even if the advertised products had no connection with baseball. In 1868, Peck and Snyder, a sporting goods store in New York, began producing trade cards featuring baseball teams.[7] Peck and Snyder sold baseball equipment, and the cards were a natural advertising vehicle. The Peck and Snyder cards are sometimes considered the first baseball cards.

Typically, a trade card of the time featured an image on one side and information advertising the business on the other. Advances in color printing increased the appeal of the cards. As a result, cards began to use photographs, either in black-and-white or sepia, or color artwork, which was not necessarily based on photographs. Some early baseball cards could be used as part of a game, which might be either a conventional card game or a simulated baseball game.[8]

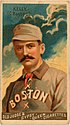

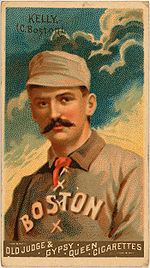

By early 1886, images of baseball players were often included on cigarette cards with cigarette packs and other tobacco products. This was partly for promotional purposes and somewhat because the card helped protect the cigarettes from damage.

As the popularity of baseball spread to other countries, so did baseball cards. By the end of the century, production had spread well beyond the Americas and into the Pacific Isles.[9] Sets appeared in Japan as early as 1898,[9] in Cuba as early as 1909[10] and in Canada as early as 1912.[11]

1900–1920

[edit]

By the turn of the century, most baseball cards were produced by confectionery and tobacco companies. Bread Companies, Game Companies, & many other types of companies also produced cards. The first major set of the 20th century was issued by the Breisch-Williams Company in 1903.[13] Breisch-Williams was a confectionery company based in Oxford, Pennsylvania. Soon after, several other companies began advertising their products with baseball cards. This included but was not limited to, the American Tobacco Company, the American Caramel Company, the Imperial Tobacco Company of Canada, and Cabañas, a Cuban cigar manufacturer.

The American Tobacco Company decided to introduce baseball advertising cards into their tobacco products with the issue of the T206 White Border Set in 1909.[14] The cards were included in packs of cigarettes and produced over three years until the company was dissolved. The most famous card, and most expensive for the grade, is the Honus Wagner card from this set; Wagner objected, so only a small number were ever distributed. According to cardboardconnection.com, as of 2015, it is estimated that less than 60 of the T206 Honus Wagner cards still exist. By last count, there were 57 known examples.[15] In 2021, a T206 Wagner card was sold in a private sale for $7.5 million, a record amount for a sports card.[16][15] Another famous one, from 1911, is Joe Tinker.[17][18]

At the same time, many other non-tobacco companies started producing and distributing baseball trade cards to the public. Between 1909 and 1911, The American Caramel Company produced the E90-1 series, and 1911 saw the introduction of the 'Zee Nut' card. These sets were produced over 28 years by the Collins-McCarthy Company of California. By the mid-teens, companies such as The Sporting News magazine began sponsoring card issues. Caramel companies like Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein were among the first to put 'prizes' in their boxes. In 1914, they produced the first of two Cracker Jack card issues, which featured players from both major leagues as well as players from the short-lived Federal League. The Chicago-based Boston Store Department company also issued a set as the teens drew to a close.

1920–1930

[edit]After the end of World War I in 1918, baseball card production lulled for a few years as foreign markets were not yet developed and the United States economy was transitioning away from wartime production. This trend would continue until the late 1930s when the effects of the Great Depression finally hit. The twenties produced a second influx of caramel cards, a plethora of postcard issues, and a handful of cards from different regions of the world. During the first two years, an influx of strip cards hit the market. These cards were distributed in long strips and often cut by the consumer or the retailer in the store. The American Caramel Company re-emerged as a baseball card producer and started distributing sets in 1922–1923. Few, if any cards were produced in the mid-twenties until 1927 when companies like York Caramel of York, Pennsylvania started making baseball cards. Cards with similar images as the York Caramel set were produced in 1928 for four ice cream companies, Yuengling's, Harrington's, Sweetman and Tharp's. In 1921, the Exhibit Supply Company of Chicago started to release issues on postcard stock. Although they are considered a postcard issue, many cards had statistics and other biographical information on the back.[19]

1920 saw the emergence of foreign markets after what was essentially an eight-year hiatus. Canadian products found their way to the market, including products branded by the Peggy Popcorn and Food Products company of Winnipeg, Manitoba from 1920 to 1926 and Willard's Chocolate Company from 1923 to 1924. Other Canadian products came from ice cream manufacturers in 1925 and 1927, from Holland Creameries and Honey Boy, respectively. Billiken Cigars, a.k.a. "Cigarros Billiken", were distributed in Cuba from 1923 to 1924.

1930–1950

[edit]

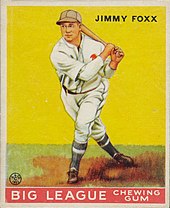

In the early 1930s, production soared, starting with the 1932 U.S. Caramel set. The popular 1933 Goudey Gum Co. issue, which included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig cards, best identifies this era. In contrast to the economical designs standard in earlier decades, this card set featured bright, hand-colored player photos on the front. In addition, the backs provided brief biographies and personal information such as height, weight, and birthplace. The 240-card set, quite large for the time, included current players, former stars, and prominent minor leaguers. Individual cards measured 2+3⁄8 by 2+7⁄8 inches (6.0 by 7.3 cm), which Goudey printed on 24-card sheets and distributed throughout the year.[20] The bulk of early National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees appear in this set.

1933 also saw the delivery of the World Wide Gum issue. World Wide Gum Co. was based in Montreal and had a close relationship with the Goudey Gum Company, as each of their four issues closely resembled a Goudey contemporary. Goudey, National Chicle, Delong, and a handful of other companies were competitive in the bubble gum and baseball card market until World War II began.

After 1941, cards would not be produced in any significant numbers until a few years after the end of the war. Then, wartime production transitioned into the post-war civilian consumer goods, and in 1948 baseball card production resumed in the U.S. with issues by the Bowman Gum and the Leaf Candy Company. At the same time, Topps Gum Company issued their Magic Photos set four years before they issued their first "traditional" card set.[21] By 1950, Leaf had bowed out of the industry.

Japanese baseball cards became more numerous in 1947 and 1950. The cards were associated with Menko, a Japanese card game. Early baseball menko were often round and were printed on thick cardboard stock to facilitate the game.[22]

1948–1980

[edit]Bowman was the major producer of baseball cards from 1948 to 1952. In 1952, Topps began to produce large sets of cards as well, releasing its first, created by Topps employee Sy Berger and publisher, Woody Gelman. The set is considered by collectors as the first modern baseball card set due to the new full-color photos, facsimile autographs, and the inclusion of statistics and bios printed on the back.[23][24] The 1952 Topps set is the most sought-after post-World War set among collectors because of the scarcity of the Mickey Mantle rookie card, the first Mantle card issued by Topps.[25] Although it is not his true rookie card (that honor belongs to his 1951 Bowman card), it is still considered the ultimate card to own of the post-war era.[26]

Topps and Bowman then competed for customers and the rights to any baseball players' likeness. Two years later, Leaf stopped producing cards. In 1956, Topps bought out Bowman and enjoyed a largely unchallenged position in the U.S. market for the next two decades. From 1952 to 1969, Topps always offered five- or six-card nickel wax packs, and in 1952–1964 also offered one-card penny packs.[27][28]

In the 1970s, Topps increased the cost of wax packs from 10 to 15 cents (with 8–14 cards depending on year) and also offered cello packs (typically around 18–33 cards) for 25 cents.[29] Rack packs containing 39–54 cards could also be had for between 39 and 59 cents per pack.[30]

This did not prevent a large number of regional companies from producing successful runs of trading cards. Additionally, several U.S. companies attempted to enter into the market at a national level. In 1959, Fleer, a gum company, signed Ted Williams to an exclusive contract and sold a set of cards featuring him.[31] Williams retired in 1960, forcing Fleer to produce a set of Baseball Greats cards featuring retired players.[32] Like the Topps cards, they were sold with gum. In 1963, Fleer produced a 67-card set of active players (this time with a cherry cookie in the packs instead of gum), which was unsuccessful, as most players were contractually obligated to appear exclusively in Topps trading card products. Post Cereals issued cards on cereal boxes from 1960 to 1963, and sister company Jell-O issued virtually identical cards on the backs of its packaging in 1962 and 1963.

In 1965, Topps licensed production to Canadian candy maker O-Pee-Chee. The O-Pee-Chee sets were identical to the Topps sets until 1969 when the backs of the cards were branded O-Pee-Chee. In 1970, due to federal legislation, O-Pee-Chee was compelled to add French-language text to the backs of its baseball cards.[33]

In the 1970s, several companies took advantage of a new licensing scheme, not to take on Topps but to create premiums. For example, Kellogg's began to produce 3D-cards inserted with cereal and Hostess printed cards on packages of its baked goods.

In 1976, a company called TCMA, which mainly produced minor league baseball cards, produced a set of 630 cards consisting of Major League Ball players. The cards were produced under the Sports Stars Publishing Company, or SSPC. TCMA published a baseball card magazine named Collectors Quarterly, which it used to advertise its set, offering it directly via mail order. Due to a manufacturers' agreement, the cards were available directly from TCMA and were not made available again, like other sets issued by TCMA.

1981–1994

[edit]Fleer sued Topps in 1975 to break the company's monopoly on baseball cards and won, as in 1980, federal judge Clarence Charles Newcomer ended Topps Chewing Gum's exclusive right to sell baseball cards, allowing the Fleer Corporation to compete in the market.[34][35] In 1981, Fleer and Donruss issued baseball card sets, both with gum. An appeal of the Fleer lawsuit by Topps clarified that Topps' exclusive rights only applied to cards sold with gum.[36] After the appeal, Fleer and Donruss continued to produce cards issued without gum; Fleer included team logo stickers with their card packs, while Donruss introduced "Hall of Fame Diamond Kings" puzzles and included three puzzle pieces in each pack. In 1992, Topps' gum and Fleer's logo stickers were discontinued, with Donruss discontinuing the puzzle piece inserts the following year.[37] With the issuance of a very popular and rare (compared to other sets at the time) set in 1984, Donruss began to take hold as one of the most popular card brands in competition with Topps. In particular, several rookie cards in the 1984 Donruss set are still considered the most desirable cards from that year of any brand (especially the Don Mattingly rookie card). Also in 1984, two monthly price guides came on the scene. Tuff Stuff and Beckett Baseball Card Monthly, published by Dr. James Beckett, attempted to track the approximate market value of several types of trading cards.

[38] More collectors entered the hobby during the 1980s. As a result, manufacturers such as Score (which later became Pinnacle Brands) and Upper Deck entered the marketplace in 1988 and 1989 respectively. Upper Deck introduced several innovative production methods including tamper-proof foil packaging, hologram-style logos, and higher-quality card stock. This style of production allowed Upper Deck to charge a premium for its product, becoming the first mainstream baseball card product to have a suggested retail price of 99 cents per pack. In 1989, Upper Deck's first set included the Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card. Eighteen-year-old employee, Tom Geideman, selected the players for the inaugural 1989 set proposing Griffey, a minor leaguer at the time, for the coveted #1 spot.[39] Griffey had yet to make his major league debut with the Seattle Mariners, so in order to create his rookie card, an image of him in his San Bernardino Spirits uniform was altered. The uniform was airbrushed royal blue, and the star on his hat was replaced with a yellow “S”.[40] The card became highly sought-after until Griffey's persistent injury troubles caused his performance level to decline.[37] As of the summer of 2022, Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) certified over 4,000 copies of the 1989 Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card were graded a 10, or Gem Mint status.[41]

The other major card companies followed suit and created card brands with higher price points. Topps resurrected the Bowman brand name in 1989. Topps produced a Stadium Club issue in 1991. 1992 proved to be a breakthrough year as far as the price of baseball cards was concerned, with the previous 50-cents per pack price being replaced by higher price points, overall higher-grade cardboard stock, and the widespread introduction of limited edition "inserts" across all product lines. 1992 was the beginning of the collectors' chase for "gold foil," which was commonly stamped on the limited edition "insert" cards. Notable examples from 1992's "insert" craze include Donruss Diamond Kings, which included gold-foil accents for the first time ever, and Fleer's host of gold foil-accented "insert" cards, including All-Stars and Rookie Sensations. 1992 was also the first year that "parallel" cards were introduced. In 1992, Topps produced Topps Gold "insert" cards of each card in the standard base set. The "parallel" Topps Gold cards had the player's name and team stamped in a banner of "gold foil" on the card front. The "parallel" moniker became popular to describe these cards because each and every card in the standard base set had an accompanying "insert" variation. In 1993, the card companies stepped up the "premium" card genre with "super premium" card sets, with Fleer debuting its "Flair" set and Topps debuting its "Topps Finest" set. Topps Finest was the first set to utilize refractors, a technology that utilized a reflective foil technology that gave the card a shiny "rainbow" appearance that proved extremely popular among hobbyists. Other notable "premium" card sets from the 1990s are as follows: Donruss issued its Leaf brand in 1990; Fleer followed with Fleer Ultra sets in 1991; and Score issued Pinnacle brand cards in 1992.[37]

1995–current

[edit]Starting in 1997 with Upper Deck, companies began inserting cards with swatches of uniforms and pieces of game-used baseball equipment as part of a plan to generate interest. Card companies obtained all manner of memorabilia, from uniform jerseys and pants, to bats, gloves, caps, and even bases and defunct stadium seats to feed this new hobby demand.[37] It is also in 1997 that the first "one-of-one" cards were released by Fleer, beginning with the 1997 Flair Showcase "Masterpieces" (the Ultra set would begin to include purple 1-of-1 masterpieces the following year). Both kinds of inserts remain popular staples in the hobby today.

The process and cost of multi-tiered printings, monthly set issues, licensing fees, and player-spokesman contracts made for a difficult market. Pinnacle Brands folded after 1998. Pacific, which acquired full licensing in 1994, ceased production in 2001. In 2005, Fleer went bankrupt and was bought out by Upper Deck, and Donruss lost the MLB license in 2006 (they also did not produce baseball cards in 1999 and 2000). At that time, the MLBPA limited the number of companies that would produce baseball cards to offset the glut in product, and to consolidate the market.[42] As a result of the measure that included revoking the MLB/MLBPA production licenses from Donruss, only two companies remained; Topps and Upper Deck.[37]

Topps and Upper Deck are the only two companies that retained production licenses for baseball cards of major league players. In a move to expand their market influence, Upper Deck purchased the Fleer brand and the remnants of its production inventory. After purchasing Fleer, Upper Deck took over production of the remaining products that were slated to be released. Upper Deck continues to issue products with the Fleer name, while Topps continues to release Bowman and Bazooka card products. Topps is also the only company that continues to produce pre-collated factory sets of cards.[37]

Card companies are trying to maintain a sizable hobby base in a variety of ways. Especially prominent is a focus on transitioning the cards to an online market. Both Topps and Upper Deck have issued cards that require online registration, while Topps has targeted the investment-minded collector with its eTopps offering of cards that are maintained and traded at its website.[43] Also, since the late 1990s, hobby retail shops and trade-show dealers found their customer base declining, with their buyers now having access to more items and better prices on the Internet. As more collectors and dealers purchased computers and began trusting the Internet as a "safe" venue to buy and sell, the transformation from the traditional retail shops and shows to Internet transactions changed the nature of the hobby.

During the same time period, MLBPA also introduced a new guideline for players to attain a rookie card. For years, players had been highlighted in previous sets as a rookie while still in the Minor Leagues. Such players would sometimes remain in the Minor Leagues for considerable time before attaining Major League status, making a player's rookie card released years before their first game as a major leaguer. The new guideline requires players to be part of a Major League team roster before a rookie card would be released in their name, and a designated "rookie card" logo printed on the face of the card. The rookie card logo shows the words "rookie card" over a baseball bat and home plate with the Major League Baseball logo in the top left corner.

Baseball cards garnered national media attention again in early 2007, when it was found that Topps' new Derek Jeter card had allegedly been altered just prior to final printing. A reported prankster inside the company had inserted a photo of Mickey Mantle into the Yankees' dugout and another showing a smiling President George W. Bush waving from the stands. Topps Spokesman Clay Luraschi later admitted that it was done on purpose by the Topps creative department.[44]

In February 2007, one of the hobby's most expensive card, a near mint/mint professionally graded and authenticated T206 Honus Wagner, was sold to a private collector for $2.35 million.[45] The card was sold again later that same year for a record-setting $2.8 million.[46]

Throughout the 20th century, baseball cards were always made from cardboard. Now, companies use other materials that they claim can withstand being soaked in salt water.[47]

In 2012, Topps created the Topps Bunt digital trading card app. The app has gained over 2 million users from more than 50 countries.[48]

In 2020, baseball cards—and sports cards as a whole—received a big boost in popularity, with many citing the COVID-19 pandemic as a contributing factor.[49][50]

Attributes

[edit]The obverse (front) of the card typically displays an image of the player with identifying information, including, but not limited to, the player's name and team affiliation. The reverse of most modern cards displays statistics and/or biographical information. Many early trade cards displayed advertisements for a particular brand or company on the back. Tobacco companies were the most instrumental in the proliferation of baseball cards, which they used as value added bonuses and advertisements for their products.[51] Although the function of trading cards had much in common with business cards, the format of baseball cards initially most resembled that of playing cards. An example, is the design of 1951 Topps Baseball cards.

While there are no firm standards that limit the size or shape of a baseball card, most cards of today are rectangular, measuring 2+1⁄2 by 3+1⁄2 inches (6.4 by 8.9 cm).[52]

Classification: the type card

[edit]Since early baseball cards were produced primarily as a marketing vehicle, collectors began to classify those cards by the 'type' of company producing the set. The system implemented by Jefferson Burdick in The American Card Catalog has become the de facto standard in identifying and organizing trade cards produced in the Americas pre-1951. The catalog itself extends into many other areas of collecting beyond the sport of baseball. Sets like 1909–1911 White Borders, 1910 Philadelphia Caramels, and 1909 Box Tops are most commonly referred to by their ACC catalog numbers (T206, E95, and W555, respectively).

Rare cards

[edit]The most valuable cards are worth millions. One T206 Honus Wagner card was sold at auction in May 2021 for $3,750,000.[53] A 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle card, graded as PSA 9 on a scale of 1 (worst) to 10 (best), sold for $2,880,000 in 2018.[54] Another Topps 1952 Mickey Mantle card, graded 9.5 by SGC, sold for $12,600,000 in August 2022, becoming the most valuable sports card and item of sports memorabilia of any sort of all time.[55][56] Condition can play a huge role in the price. Other 1952 Topps Mantle cards, graded 1, have sold for as little as a few thousand dollars.[57]

Collectors and dealers

[edit]Vintage baseball cards have been a prime focus of countless collectors and historians of one of America's favorite pastimes. Since rare baseball cards are difficult to find, collectors seek for ways to be aware of the rare cards that come into the trading or selling market. Baseball card collectors normally obtain them from other card collectors or from specialized dealers. Some dealers may sell rare baseball cards over the internet, very often on eBay.[58]

Rare baseball cards may also be purchased at major baseball card shows. These events are held periodically in different cities, allowing baseball card collectors and dealers to meet. In valuing a card, the potential buyer takes into consideration the condition (or graded condition) of the card. Rookie cards,[59] players' first cards, are the most valuable ones.

Sports card catalogs are a main source of obtaining detailed information on baseball cards. Online catalogs typically also contain tools for collection management and trading platforms.

Alan Rosen was a high-profile card dealer, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1986, he purchased a previously unknown trove of baseball cards, the "1952 Topps Find"; he claimed to have paid upwards of $125,000 (including a finder's fee and police protection) for 5500 cards. He sold an ungraded Mickey Mantle for $1000 that year, bought it back for $40,000 in 1991 and quickly flipped it to Anthony Giordano for $50,000. That card was sold at auction for a new record price for all sports memorabilia in 2023 - $12,600,000, including buyer's premium - shattering the previous record for a baseball card (a T206 Honus Wagner, for $6,600,000 in 2021) and for sports memorabilia (the jersey Diego Maradona was wearing when he scored the infamous "hand of God" goal in the 1986 World Cup, for $9,300,000 in 2022).[55]

Markets

[edit]United States

[edit]Baseball cards in the United States have gone through numerous changes in everything from production and marketing to distribution and use. The earliest cards were targeted primarily at adults as they were produced and associated by photographers selling services and tobacco companies in order to market their wares. By the early 1910s, many cards were issued as part of games and confection companies began to distribute their own card sets.

The market in the United States has been particularly affected by issues both sports and non-sports related. Economic effects of World War I, World War II, and the Great Depression have all had a major impact on the production of cards. For example, World War I suppressed baseball card production to the point where only a handful of sets were produced until the economy had transitioned away from wartime industrialization.[60] The 1994 players' strike caused a decline in interest and industry consolidation.[citation needed] Yet, with the advent and acceptance of third-party companies bringing greater objectivity in the grading of baseball cards (coupled with online marketing), the vintage baseball card business has become quite popular again, with sales in the multi-millions of dollars recorded every year for at least ten years. Player performance records and other demand variables are reflected by baseball card prices.[61]

The Topps monopoly

[edit]Topps' purchase of Bowman led to a stranglehold on player contracts. Since Topps had no competition and there was no easy way for others to break into the national market, the company had a de facto monopoly. However, several regional sets featuring players from local teams, both major league and minor league, were issued by various companies.

Over the years, there was also a great deal of resistance from other companies. In 1967, Topps faced an attempt to undermine its position from the Major League Baseball Players Association, the League's nascent players' union. Struggling to raise funds, the MLBPA discovered that it could generate significant income by pooling the publicity rights of its members and offering companies a group license to use their images on various products. After initially putting players on Coca-Cola bottlecaps, the union concluded that the Topps contracts did not pay players adequately for their rights.

Fleer even filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission alleging that Topps was engaged in unfair competition through its aggregation of exclusive contracts. A hearing examiner ruled against Topps in 1965, but the Commission reversed this decision on appeal. The Commission concluded that because the contracts only covered the sale of cards with gum, competition was still possible by selling cards with other small, low-cost products. However, Fleer chose not to pursue such options and instead sold its remaining player contracts to Topps for $395,000 in 1966.[62]

Soon after, MLBPA executive director Marvin Miller then approached Joel Shorin, the president of Topps, about renegotiating these contracts. At this time, Topps had every major league player under contract, generally for five years plus renewal options, so Shorin declined. After continued discussions went nowhere, before the 1968 season, the union asked its members to stop signing renewals on these contracts, and offered Fleer the exclusive rights to market cards. Although Fleer declined the proposal, by the end of 1973, Topps had agreed to double its payments to each player from $125 to $250, and also to begin paying players a percentage of Topps' overall sales.[63] The figure for individual player contracts has since increased to $500. Since then, Topps used individual player contracts as the basis for its baseball cards.

Fleer vs. Topps

[edit]In April 1975, Fleer asked for Topps to waive its exclusive rights and allow Fleer to produce stickers, stamps, or other small items featuring active baseball players. Topps refused, and Fleer then sued both Topps and the MLBPA to break the Topps monopoly. After several years of litigation, the court ordered the union to offer group licenses for baseball cards to companies other than Topps. Fleer and another company, Donruss, were thus allowed to begin making cards in 1981. Fleer's legal victory was overturned after one season, but they continued to manufacture cards, substituting stickers with team logos for gum. Donruss distributed their cards with a Jigsaw puzzle piece.

Canada

[edit]The history of baseball cards in Canada is somewhat similar to that of baseball cards in the United States. The first cards were trade cards, then cards issued with tobacco products and later candies and gum. World Wide Gum and O-Pee-Chee both produced major sets during the 1930s.

In 1952, Topps started distributing its American made cards in Canada. In 1965 O-Pee-Chee re-entered the baseball card market producing a licensed version of the Topps set. From 1970 until the last Topps based set was produced in 1992 the cards were bi-lingual French/English to comply with Canadian law[64][65]

From 1985 until 1988, Donruss issued a parallel Canadian set under the Leaf name. The set was basically identical to the Donruss issues of the same years however it was bi-lingual. All the Leaf sets were produced in the United States.

There were several promotional issues issued by Canadian firms since Major League Baseball began in Canada in 1969. There were also several public safety sets issued, most notably the Toronto Blue Jays fire safety sets of the 1980s and early 1990s and the Toronto Public Libraries "Reading is fun" set of 1998 and 1999. These sets were distributed in the Toronto area. The cards were monolingual and only issued in English.

Japan

[edit]The first baseball cards appeared in Japan in the late 19th century. Unlike American cards of the same era, the cards utilized traditional Japanese pen-and-ink illustrations. In the 1920s, black-and-white photo postcards were issued, but illustrated cards were the norm until the 1950s. That decade brought about cards which incorporated photos of players, mostly in black and white. Menko cards also became popular at the time.

NPB branded baseball cards are currently widely available in Japanese toy stores, convenience stores, sports stores, and as bonus items included in certain packages of potato chips.

Starting in 2021, Topps has distributed NPB baseball cards, with the same design as the MLB releases. Boxes sell for ¥13,200 on Topps' Japan website.[66][67]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 1987 and 1988 the American company Topps issued two series of American baseball cards featuring cards from American and Canadian Major League Baseball teams in the UK. The full color cards were produced by Topps Republic of Ireland subsidiary company and contained explanations of baseball terms. Given baseball's lack of popularity in the United Kingdom, the issues were unsuccessful.

Latin America

[edit]Topps issued licensed sets in Venezuela from 1959 to 1977.[68] Most of the set had Spanish in place of the English text on the cards and the sets included winter league players. There were locally produced cards depicting players from the winter leagues produced by Offset Venezolana C.A., Sport Grafico, and others which were in production until the late 1990s.

In Cuba, sets were issued first in the early 1900s. By the 1930s various candy, gum and chocolate makers were offering cards, most notably Baguer Chocolate. The post-World War Two era had cards issued by magazines, candy makers, Coca-Cola, and of course a gum company. In post revolution Cuba, baseball cards were still issued.

Several sets of Mexican League baseball cards have been issued in the past few years.

American made cards of Major League Baseball players-Puerto Rican and internationals-are widely available in Puerto Rico.

Australia

[edit]Australian produced baseball cards were first released in 1990 by the then newly created trading card company Futera. These cards featured players from the newly created Australian Baseball League. Subsequent baseball cards were released annually in boxed sets or foil packs until 1996 when declining interest saw production cease. No new baseball cards were released in Australia until Select Australia released six team sets of cards during the 2012-13 Australian Baseball League season.[69] This was then followed up by Dingo Trading Cards releasing multiple baseball card team sets during the 2013-14 Australian Baseball League season.[70]

Price guides

[edit]Price guides are used mostly to list the prices of different baseball cards in many different conditions. One of the most famous price guides is the Beckett price guide series. The Beckett price guide is a graded card price guide, which means it is graded by a 1–10 scale, one being the lowest possible score and ten the highest. In addition, Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) grades cards 1–10, and can authenticate autographs as well. Other grading companies include Beckett, SGC, and CGC.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Rare Pre-Civil War Baseball Card Fetches $179,250 at Auction". Reuters. July 31, 2015.

- ^ "Not Always Cardboard: Unusual Materials Used to Make Trading Cards". Sports Collectors Daily. February 10, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ "Bowman Trading Cards". The Cardboard Connection. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Rovell, Darren (March 13, 2009). "Panini Buys Donruss". CNBC. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Shea, Bill. "How the billion-dollar sports card industry collapsed and then rebounded". The Athletic. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Oldest known team baseball card, c. 1860 Brooklyn Atlantics to be auctioned July 30, 2015". Heritage Auctions.

- ^ "Early Trade Cards – the First Baseball Cards". Archived from the original on August 27, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ Suciu, Peter. "Collecting Military Tobacco Cards". Warfare History Network. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Fitts, Robert K. An Introduction to Japanese Baseball Cards.

- ^ "1909 Cabanas". Archived from the original on September 17, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ "1912 Imperial Tobacco".

- ^ "Honus Wagner T-206 Sportscard Sells for World-Record Price". Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ "1903 E103 Breisch-Williams". Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ "1887-1929 Baseball Cards Archives". The Cardboard Connection. May 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Zimmeth, Khristi (October 15, 2015). "Treasure: Baseball item so close to being 'rare' card". The Detroit News. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ Hajducky, Dan (August 4, 2022). "Rare T-206 Honus Wagner baseball card sold for record $7.25 million in private sale". ESPN. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ "Nuns auctioning rare baseball card". Associated Press. October 27, 2010. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Heitman, William R. (1980). The Sport Americana, T206, The Monster. Den's Collectors Den.

- ^ The company's baseball cards last appeared in 1966.

- ^ "1933 Goudey R319: A Closer Look at One of the Hobby's "Big Three"". Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ^ "Topps Magic Photos". Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ Gall, John (2006). Sayonara Home Run!. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA.

- ^ Prothro, Jacob (April 4, 2018). "Dallas auction house expects Mickey Mantle rookie card to set new record". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Prewitt, Alex (July 6, 2021). "Mickey Mantle, Chairman of the Cardboard". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "1952 Topps Baseball Checklist, Set Info, Key Cards, Hot List, Analysis". The Cardboard Connection. June 23, 2015.

- ^ Gilbert, Steve (April 22, 2010). "Kendrick's baseball cards find way to Hall". Major League Baseball. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ "1950-1959 Baseball Cards Checklists, Set Details, Reviews, Buying Guide". The Cardboard Connection. July 13, 2015.

- ^ "1960-1969 Baseball Cards Archives". The Cardboard Connection. July 3, 2015.

- ^ "1970-1979 Baseball Cards Archives". The Cardboard Connection. November 16, 2012.

- ^ "A Guide to 1975-1979 Topps Baseball Cards". Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ "1959 Fleer Ted Williams Baseball Checklist, Set Info, Buying Guide". The Cardboard Connection. July 2, 2015.

- ^ "1960 Fleer Baseball Checklist, Set Info, Key Cards, Buying Guide, More". The Cardboard Connection. July 3, 2015.

- ^ "O-Pee-Chee Cards". Archived from the original on October 30, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ Douglas Martin (August 28, 2005). "Clarence Newcomer, 82, Longtime Federal Judge," South Florida Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Ravo, Nick (August 1, 1999). "Gilbert Barclay Mustin, 78, Developed Fleer Baseball Cards". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ International Directory of Company Histories | Donruss Playoff L.P. | Production of Baseball Cards Begins in 1981[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f 2006 Beckett Almanac of Baseball Cards and Collectibles

- ^ Zillante, Arthur. "A Post-War Review of the Baseball Card Market" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ Passan, Jeff (July 22, 2016). "What the iconic 1989 Ken Griffey Jr. Upper Deck card means to a generation of fans". Yahoo Sports. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Winn, Luke (August 24, 2009). "The Last Iconic Baseball Card". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Reuter, Joel (August 31, 2022). "Sports Cards: Predicting the Next $10 Million Card After Mickey Mantle Sale". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Baseball trading cards focus on future growth". MLB Players Association. July 21, 2005. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "etopps – about etopps". The Topps Company. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Card trick: Bush, Mantle cheer Jeter in gag image

- ^ "Honus Wagner card sold for $2.35 million". NBC Sports, MSNBC. Associated Press. February 27, 2007. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Honus Wagner card sells for record $2.8 million". ESPN. Associated Press. September 6, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Shoebox Treasures | Baseball Hall of Fame". baseballhall.org. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Topps Bunt Digital Baseball Cards". CardDugout.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Sports cards are back in a big way -- pandemic, recession and all". ESPN.com. October 2, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Baseball cards are booming during the pandemic, with long lines, short supplies and million-dollar sales". Chicago Tribune. February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Baseball Cards Section Archived 2012-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Cardboard Connection

- ^ "Topps Sports History". Archived from the original on September 10, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ negley, cassandra (May 23, 2021). "Rare Honus Wagner card sells for record $3.75 million, trails only Mike Trout in MLB cards". yahoo.

- ^ David Seideman (April 29, 2018). "Forget The $2.9 Million Mickey Mantle Card, There Are Three Worth $10 Million". Forbes.

- ^ a b Albeck-Ripka, Livia (August 28, 2022). "Baseball Card Sold for $12.6 Million, Breaking Record - The 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle baseball card is the most valuable piece of sports memorabilia ever to be sold at auction". The New York Times. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ "'52 Mantle card found in attic sold for $12.6M". MLB.com.

- ^ "Auction Prices Realized Baseball Cards 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle". PSA Authentication & Grading Services.

- ^ How to collect baseball cards Archived July 28, 2012, at archive.today Diamond Fans baseball portal. Retrieved on February 16, 2010

- ^ "Baseball : Sports Cards [Special Feature: Rookie Card] [1/30]". colnect.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "The Senate and the 1994-95 Baseball Strike". United States Senate. US Senate. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Thomas H.; Sen, Kabir Chandra (January 1, 2023). "Analytics and baseball card values". Managerial Finance. 50 (2): 386–395. doi:10.1108/MF-05-2023-0325. ISSN 0307-4358.

- ^ Vrechek, George (December 3, 2008). "Philly Phavorite: Irv Lerner". F+W Media, Inc. Sports Collectors Digest. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Fleer Corporation v. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. and Major League Baseball Players Association, 658 F.2d 139, 19–21, 57 (United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit. 1981).

- ^ "A Brief History Of O-Pee-Chee". Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ^ "CBC.ca – Arts – Alternative Canadian Walk of Fame – Inductee: O-Pee-Chee". CBC News. Archived from the original on September 18, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ^ Treutel, Trey (October 17, 2022). "2022 Topps NPB Nippon Professional Baseball Cards Checklist & Odds". The Cardboard Connection. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Treutel, Trey (December 30, 2021). "2021 Topps NPB Nippon Professional Baseball Cards Checklist". The Cardboard Connection. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Topps Venezuela Baseball Cards". mybaseballcardspace.info.

- ^ "Select Australia Cards adds ABL to collection - Australian Baseball League News". Australian Baseball League.

- ^ East, Adam (November 1, 2013). "Australian Custom Baseball Cards: Dingo 2013-14 ABL Cards - Canberra Cavalry Championship Edition Set and Further Release Info".

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Baseball cards at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Baseball cards at Wikimedia Commons