John Sentamu

The Lord Sentamu | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of York and Primate of England | |

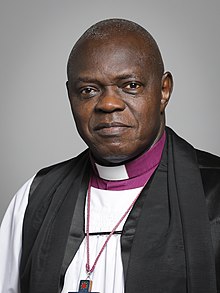

Official portrait, 2019 | |

| Province | York |

| Diocese | York |

| In office | 2005–2020 |

| Predecessor | David Hope |

| Successor | Stephen Cottrell |

| Other post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1979 |

| Consecration | 25 September 1996 by George Carey |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Tucker Mugabi Sentamu 10 June 1949 Kampala, Uganda |

| Nationality | British |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Parents | John and Ruth Walakira[1] |

| Spouse |

Margaret Wanambwa (m. 1973) |

| Children | 2[2] |

| Occupation | Life peer |

| Profession | Cleric, lawyer |

| Alma mater | |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Assumed life peerage 25 May 2021 | |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| In office 25 January 2006 – 7 June 2020 | |

John Tucker Mugabi Sentamu, Baron Sentamu, PC (/ˈsɛntəmuː/;[3] Luganda pronunciation: [sːéːntámû]; born 10 June 1949) is a retired Anglican bishop and life peer. He was Archbishop of York and Primate of England from 2005 to 2020. In retirement he was subject to investigation over his handling of child sexual abuse allegations and was asked to step back from ministry because of his mishandling of deviant clergy. [4]

Born near Kampala in Uganda, Sentamu studied law at Makerere University before gaining employment as an advocate of the Supreme Court of Uganda. Speaking out against the regime of President Idi Amin, he was briefly imprisoned before fleeing in 1974 to the United Kingdom, where he devoted himself to Anglicanism, beginning his study of theology at Selwyn College, Cambridge, in 1976 and eventually gaining a doctorate in 1984. He studied for ordination at Ridley Hall, Cambridge, and was ordained in 1979. In 1996 he was consecrated as the area bishop of Stepney and in 2002 became Bishop of Birmingham. In 2005 he was appointed to the office of Archbishop of York.

He has also received attention for his vocal criticism of former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe.

Sentamu was omitted from the first list of new peerages following his resignation as archbishop,[5] but it was announced in December 2020 that Sentamu would be created a crossbench life peer in the second list of 2020 Political Honours.[6]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Sentamu was born in 1949 in Masooli village, Gayaza, near Kampala, Uganda, the sixth of thirteen children. He obtained an LLB degree from Makerere University, Kampala in 1971, and practised as an advocate of the High Court of Uganda until 1974, being briefly a judge of the High Court. In 1973, he married his wife Margaret who is a deacon.[7] Three weeks after his marriage, he incurred the wrath of the dictator Idi Amin and was detained for 90 days. In a speech in 2007, he described how during that time he had been "kicked around like a football and beaten terribly", saying "the temptation to give up hope of release was always present".[8] He fled his home country to arrive as an immigrant in the United Kingdom in 1974.[9]

Education and early ministry

[edit]Sentamu studied theology at Selwyn College, Cambridge, where he subsequently received a BA degree in 1976, promoted to the Cambridge MA in 1979, and a PhD degree in 1984. He trained for the priesthood at Ridley Hall, Cambridge, being ordained a priest in 1979. His doctoral thesis is entitled "Some aspects of soteriology, with particular reference to the thought of J. K. Mozley, from an African perspective".[10] He worked as assistant chaplain at Selwyn College, as chaplain at a remand centre and as curate and vicar in a series of parish appointments.[citation needed]

Sentamu was consecrated a bishop on 25 September 1996 by George Carey, Archbishop of Canterbury, at St Paul's Cathedral;[11] to serve as Bishop of Stepney, a suffragan and area bishop in the Diocese of London. It was during this time that he served as advisor to the Stephen Lawrence Judicial Enquiry. In 2002 he chaired the Damilola Taylor review. That same year he was appointed Bishop of Birmingham where his ministry, according to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, was praised by "Christians of all backgrounds".[citation needed] Sentamu became President of Youth for Christ in 2004 and President of the YMCA in April 2005.[12]

Archbishop of York

[edit]On 17 June 2005 the prime minister's office announced Sentamu's translation to York as the 97th archbishop.[13] He was formally elected by the chapter of York Minster on 21 July,[14] legally confirmed as archbishop at St Mary-le-Bow, London on 5 October,[15] and enthroned at York Minster on 30 November 2005 (the feast of Saint Andrew), at a ceremony with African singing and dancing and contemporary music, with Sentamu himself playing African drums during the service.[16][17] As Archbishop of York, Sentamu sat in the House of Lords[18] and was admitted, as a matter of course, to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom.[19] He was the first black archbishop in the Church of England.[16][13]

For a week in August 2006, Sentamu camped in York Minster, forgoing food in solidarity with those affected by the Middle East conflict, especially the children and other civilians killed and injured during the 2006 Lebanon War, when cluster bombs were used by Israeli forces.[20][21][22]

On 7 March 2007, Sentamu was installed as the first Chancellor of York St John University. On 1 June 2007 he was appointed as the first Chancellor of the University of Cumbria. He took up the position when the university opened on 1 August 2007.[23] In July 2009, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by University of Chester.[24] On 15 July 2010, Sentamu was presented with an honorary degree from the University of York by the Provost of Vanbrugh College, David Efird of the Department of Philosophy,[25] and on 16 July 2010 was presented with an honorary degree from the University of Leeds by the chancellor of the university, Melvyn Bragg.[26]

On 16 July 2007, Sentamu was presented with an honorary degree from the University of Hull by the chancellor of the university, Virginia Bottomley, at Hull City Hall during the graduation ceremony for graduands of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.[27] On 19 July 2007 he was presented with an honorary degree (Doctor of Letters) from the University of Sheffield in recognition of his distinguished career as a scholar and theologian.[28]

In October 2007 Sentamu was awarded the "Yorkshireman of the Year" title by the Black Sheep Brewery. In his acceptance speech he praised the welcome he had received from the people of Yorkshire and made reference to the "African-Yorkshire DNA connection", joking that perhaps his parents had this in mind when they gave him the name "Mugabi", which, spelled backwards, is "Ibagum" ("ee-by-gum", a stock phrase popularly supposed to be used to express shock or disbelief in northern England).[29] In 2008 Archbishop Thurstan Church of England School in Hull was renamed Archbishop Sentamu Academy in his honour.[citation needed]

In October 2018, Sentamu announced his retirement, scheduled for 7 June 2020.[30] In June 2019, he ordained his wife as a deacon.[31]

Retirement

[edit]It was announced in the 2020 Political Honours that he would be made a life peer. On 27 April 2021 he was created Baron Sentamu, of Lindisfarne in the County of Northumberland and of Masooli in the Republic of Uganda.[32] He took his seat among the lords temporal on 25 May, the last life peer to be introduced by Thomas Woodcock as Garter King of Arms.[citation needed]

Sentamu moved with his wife to Berwick and, on 14 June 2021, was licensed an honorary assistant bishop of the Diocese of Newcastle.[33]

In May 2023, he was asked to step back from active ministry by the Bishop of Newcastle after an independent review found he failed to act on a sexual abuse disclosure.[34] Sentamu acknowledged that he did not act on the disclosure but claimed it was not his responsibility as archbishop to deal with the disclosure as "the action following a disclosure to the bishop of Sheffield was his and his alone".[35] He further tried to claim that the law prevented him acting:

"Safeguarding is very important but it does not trump Church Law (which is part of the Common Law of England). And the Law is not susceptible to be used as an excuse for exercising the role given to an Archbishop. Church Law sets the boundaries for Diocesan Bishops and Archbishops."[35]

Views

[edit]Sentamu has spoken on issues including young people, the family, slavery, and injustice and conflict abroad. In an early TV appearance in 1988 he joined, among others, Ray Honeyford, Ann Dummett and Lurline Champagnie to discuss "Race and the classroom" on After Dark.[36] In November 2005 he sought re-discovery of English pride and cultural identity, stating that zeal for multiculturalism had sometimes "seemed to imply, wrongly for me, 'let other cultures be allowed to express themselves but do not let the majority culture at all tell us its glories, its struggles, its joys, its pains'."[37] In 2006 he claimed that the BBC was frightened of criticising Islam.[38]

In 2006, Sentamu featured prominently in the British press because of his comments on the treatment of detainees in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.[39]

Poverty

[edit]Sentamu regrets that many low paid workers are not paid enough to lift them and their families out of poverty.

The issue is one that strikes to the heart of the moral fabric of our society. For the very first time the majority of households in poverty in Britain have at least one person working. The nature of poverty in Britain is changing dramatically. For millions of hard-pressed people, work is no longer a route out of poverty. (...) Low pay is a scourge on our society, and we all pay for it. Low pay costs the taxpayer between 3.6 and 6 billion pounds a year in tax credits, in-work benefits and lost tax receipts. And as disposable income available to the lowest paid reduces, so too does the demand in the economy.[40]

Once upon a time you couldn't really be living in poverty if you had a regular income, you could find yourself on a low income, yes. But that is not longer so. You can be in work and still live in poverty.[41]

Sentamu believes that food poverty is causing malnutrition in the UK. In 2013, he said that "last year more than 27,000 people were diagnosed as suffering from malnutrition in Leeds – not Lesotho, not Liberia, not Lusaka but Leeds?" and feels these reports "disgrace us all, leaving a dark stain on our consciences".[41] Government welfare reforms were

"beginning to bite – with reductions in housing benefit for so-called under-occupation of social housing, the cap on benefits for workless householders and single parents, and the gradual replacement of the disability living allowance with a personal independence payment".[41]

General election

[edit]In the run up to the 2017 United Kingdom general election, Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and John Sentamu campaigned over the need to address poverty, education, housing and health. The archbishops stressed the importance of "education for all, of urgent and serious solutions to our housing challenges, the importance of creating communities as well as In the run up to the 2017 United Kingdom general election, and a confident and flourishing health service that gives support to all – especially the vulnerable – not least at the beginning and end of life."[42]

Stop and search

[edit]In 2000, Sentamu, then Bishop of Stepney, was stopped by a City of London Police officer near St Paul's Cathedral. Sentamu claimed it was the eighth time he had been questioned by police in eight years, and that he was the only Church of England bishop to have been stopped by police in this way.[43] In a 2010 debate in the House of Lords, Sentamu was critical of the standards of "reasonable grounds to suspect" applied by police.[44]

Robert Mugabe

[edit]

On 9 December 2007, during a live television interview with Andrew Marr on BBC One, Sentamu made a protest against Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. Sentamu took the white insert off his clerical shirt and cut it up stating that:

as an Anglican, this is what I wear to identify myself that I'm a clergyman. Do you know what Mugabe has done? He's taken people's identity and literally, if you don't mind [cuts up dog collar], cut it to pieces. This is what he's actually done, to a lot of—and in the end there's nothing. So as far as I'm concerned from now on I'm not going to wear a dog collar until Mugabe's gone.[45]

His protest followed criticism against Mugabe at the EU-Africa summit in Lisbon.

In December 2008, Sentamu again spoke out against Mugabe, saying "The time has come for Robert Mugabe to answer for his crimes against humanity, against his countrymen and women and for justice to be done".[46] On 26 November 2017, Sentamu returned to The Andrew Marr Show and kept his promise to reinstate his dog collar following Robert Mugabe's resignation earlier in the week. Marr presented him with an envelope containing the original cut up pieces of collar. Of it he said

You know, Andrew, I could attempt to put this one back together using superglue, but it would be a pretty ropey collar. And I actually think the lesson for Zimbabwe is the same. They just can't try and stitch it up. Something more radical, something new needs to happen.[47]

He then put on a new dog collar which he had brought with him. He also said it could be possible for Zimbabweans to forgive Mr Mugabe. "Mugabe needs to say at some point to Zimbabweans: 'Forgive me'. He's a very, very intelligent man and I think he is capable of doing it."

Financial crisis

[edit]In September 2008, Sentamu and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, spoke out against opportunistic stock market trading. Sentamu compared those who practised short selling of HBOS shares, driving the share prices down, to "bank robbers".[48]

Sexuality and marriage

[edit]

Sentamu, born in Uganda, said laws being debated in Uganda which would impose the death penalty on homosexuals and on those supporting them were "victimising". He told the BBC that the proposed law "tends to confuse all of homosexual relationships with what you call aggravated stuff and that's the problem", but that the Anglican Communion was committed to recognising that gay people were valued by God.[49] Previously, as area Bishop of Stepney, he was one of four English bishops who refused to sign the Cambridge Accord, an attempt in 1999 to find agreement on affirming certain human rights of homosexuals, notwithstanding differences within the church on the morality of homosexual behaviour.[50] In 2012 he stated his opposition to government plans to legalise same-sex marriage in the United Kingdom, asserting that "Marriage is a relationship between a man and a woman, I don't think it is the role of the State to define what marriage is" and "We've seen dictators [redefine marriage] in different contexts and I don't want to redefine very clear social structures that have been in existence for a long time."[51] At the same time, he expressed support for same-sex civil partnerships. "They [civil partnerships] are in every respect in ethical terms an honourable contract of a committed relationship."[52]

In 2016, speaking to Piers Morgan, Sentamu said that he would not call homosexuality a 'sin' and still supported civil unions while opposing same-sex marriage.[53] “I support civil partnerships because I think that’s a matter of equality, and a matter of fairness, but for me, it was wrong for the Government to try to redefine the nature of marriage" he said.[54] In 2017, Sentamu spoke out in favour of a motion at General Synod to call for the government to ban the use of conversion therapy, a controversial practice meant to change a person's sexual orientation.[55] At the same session of General Synod, Sentamu supported a motion to offer "welcome and affirmation" for transgender persons as members of the Church of England.[56]

Commenting on Prince William and Kate Middleton's decision to live together before their wedding, Sentamu said that the couple's public commitment to live their lives together today would be more important than their past. He said that he had conducted wedding services for "many cohabiting couples" during his time as a vicar in south London, and said, "We are living at a time where some people, as my daughter used to say, want to test whether the milk is good before they buy the cow."[57] He also said, "For some people that's where their journeys are. But what is important, actually, is not to simply look at the past because they are going to be standing in the Abbey taking these wonderful vows: 'for better for worse; for richer for poorer; in sickness and in health; till death us do part.'"[57]

In a speech to the House of Lords on 19 November 2007, he opposed elements of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill for seeking to remove a child's "need for a father" in the IVF process. He said: "We are now faced with a Bill which is seeking to formalise the situation where the need for the ultimate male role model – that of the father – is removed in entirety."[58]

National Trust Egg Hunt

[edit]In 2017 he criticised the National Trust for "airbrushing out" religion from the National Trust Egg Hunt.[59]

Other activities

[edit]Columnist

[edit]Sentamu has contributed to The Sun[60] tabloid newspaper, and in 2012 he contributed to the first edition of the Sun on Sunday. All the income that he derives from journalism goes to St Leonard's Hospice in York, of which he is president.[60]

In September 2007, Sentamu wrote in his column that the parents of the missing Madeleine McCann, were subject to a "whispering campaign" and were entitled to the presumption of innocence.[61]

Public baptisms

[edit]On Easter Sunday 2008, Sentamu baptised 20 people by full immersion in a tank of water outside St Michael-le-Belfrey Church in York. Hundreds of people watched the ceremony.[62]

Skydive for the Afghanistan Trust

[edit]On 6 June 2008, Sentamu completed a charity skydive from 12,500 feet with a member of the Red Devils parachute team. The dive took place over Langar Airfield in Nottinghamshire, with Sentamu aiming to raise £50,000 for the Afghanistan Trust. Yorkshire businessman Guy Brudenell had challenged Sentamu to do the jump at a charity dinner and Brudenell also took part in the jump on the day.[63] In recognition of what was described as his "pluck", Sentamu was later given honorary membership of the Parachute Regimental Association.[64]

Sentamu and Brudenell raised over £75,000.[65]

Hull Kingston Rovers

[edit]On 15 April 2011, Sentamu addressed the crowd at Craven Park before the Engage Super League Rugby league match between Hull Kingston Rovers and Wigan Warriors. He asked the crowd to join him in prayer extolling the virtues of teamwork and harmony in sport. Afterwards he was presented with a Hull KR shirt.[citation needed]

Safeguarding procedure complaints

[edit]In May 2016, Sentamu was one of six bishops accused of procedural misconduct by a survivor of child sex abuse (the accusation was to do with how the complaint was handled; none of the six was involved in the abuse). Sentamu was named in The Guardian[66] and the Church Times[67] alongside Peter Burrows, Steven Croft, Martyn Snow, Glyn Webster and Roy Williamson, as subject of Clergy Disciplinary Measure complaints owing to their inaction on the survivor's disclosure. The bishops contested the complaints because they were made after the church's required one-year limit. Sentamu had acknowledged receipt of a letter from the survivor with an assurance of "prayers through this testing time". But according to the Guardian report, no action was taken against the alleged abuser nor support offered to the survivor by the church. A spokesperson for the archbishop said that Sentamu had simply acknowledged a copy of a letter addressed to another bishop. "The original recipient of the letter had a duty to respond and not the archbishop", the spokesperson said. All six bishops appeared on a protest brochure which the survivor handed out at Steven Croft's enthronement as Bishop of Oxford.[68]

In April 2018 it was reported that Sentamu and four other bishops were under investigation by South Yorkshire Police for failure to respond properly to a report of clerical child abuse. A memo from June 2013, seen by The Times and other media revealed that Sentamu had received the allegation but recommended that 'no action' be taken. The priest against whom the allegation was made died by suicide the day before he was due in court in June 2017.[69][70][71] The Archbishop of York's office said:

The diocese of York insists that Sentamu did not fail to act on any disclosures because that responsibility lay with Ineson's local bishop, Steven Croft, who was at the time bishop of Sheffield.[72]

A Guardian editorial contrasted Archbishop Sentamu's response to a statement from Archbishop Welby at IICSA, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, in which Justin Welby stated

It is not an acceptable human response, let alone a leadership response to say “I have heard about a problem, but … it was someone else’s job to report it”.[73]

Matt Ineson, the victim and survivor at the heart of the case, has called for the resignations of Archbishop Sentamu and Bishop Steven Croft.[74]

In 2023, Lord Sentamu was asked by the Bishop of Newcastle to step back from active ministry as an assistant bishop in the Diocese of Newcastle "until both the findings and his response can be explored further" after an independent review criticised his failure to act after being told of Ineson's claim of abuse.

References

[edit]- ^ Encyclopaedia of world biography (2021). "John Sentamu biography". Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Tara (4 July 2011). "Breaking the mould". BBC. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "an archiepiscopal mnemonic". 8 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ https://www.newcastle.anglican.org/independent-learning-lessons-review--late-trevor-devamanikkam.php

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (18 October 2020). "John Sentamu peerage snub criticised as 'institutional prejudice'". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Political Peerages 2020". GOV.UK. 22 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Vallely, Paul (7 April 2012). "Dr John Sentamu: Next stop Canterbury?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Caulfield, Pam (10 May 2007). "Archbishop tells his captivity story in call to free Alan Johnson". Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Retrieved 11 January 2009. - ^ "John Sentamu: Pilgrim's progress". The Independent. 26 November 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "University of Cambridge library catalogue". Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ "London welcomes bishops". Church Times. No. 6972. 27 September 1996. p. 1. ISSN 0009-658X. Retrieved 26 June 2018 – via UK Press Online archives.

- ^ "Biography". The Archbishop of York. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b "New Archbishop of York appointed". BBC News. 17 June 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ "No. 57706". The London Gazette. 19 July 2005. p. 9331.

- ^ Church of England – Sentamu: Confirmation as Archbishop of York (Accessed 15 July 2013).

- ^ a b "First black Archbishop enthroned". BBC News. 30 November 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ Jeffery, Simon (17 June 2005). "First black Church of England archbishop appointed". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ "Peer". TheyWorkForYou. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Debrett's People of Today – John Sentamu York". Debretts.com. 6 October 1949. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ "Anglican archbishop's solidarity fast". The Irish Times. 12 August 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ "John Sentamu to fast". BBC News. 12 August 2006. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (17 August 2006). "Inside is a strange place to pitch a tent…". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- ^ "Archbishop becomes new chancellor". BBC News. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ University of Chester (13 June 2010). "Twelve of the University of Chester's recent triumphs". Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Archbishop John Sentamu receives an honorary degree". BBC News. 15 July 2010.

- ^ "John Sentamu – John Sentamu – University of Leeds". Leeds.ac.uk. 16 July 2010. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ University of Hull (16 July 2007). "News". Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

- ^ "Archbishop of York awarded honorary degree". University of Sheffield. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ "Speech by the Most Revd & Rt Hon Dr John Sentamu on accepting the Yorkshire Man of the Year Award". The Diocese of York. 26 October 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ "Archbishop of York Dr John Sentamu to retire". BBC News. October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Vicky (23 June 2019). "Archbishop of York to ordain new deacons – including his wife – at York Minster". The Press. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ "Crown Office". The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Newcastle Diocese | Archbishop Sentamu commissioned as Honorary Assistant Bishop".

- ^ "Independent Learning Lessons Review - Late Trevor Devamanikkam". Diocese of Newcastle. 13 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Ex-Archbishop of York steps down from ministry over handling of abuse case". The Northern Echo. 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ List of After Dark editions, accessed 20 September 2012.

- ^ Gledhill, Ruth (30 November 2005). "Multiculturalism has betrayed the English, Archbishop says". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ Petre, Jonathan (15 November 2006). "BBC frightened of criticising Islam, says archbishop". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Herbert, Ian; Russell, Ben (18 February 2006). "The Americans are breaking international law..." The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ "For millions of people, work is no longer a way out". The Independent. 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Archbishop attacks UK food poverty". The Guardian. 19 November 2013.

- ^ "Archbishops raise election concerns in letter". ITV News. 6 May 2017.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (24 January 2000). "Black bishop 'demeaned' by police search". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Volume No. 720 – 27 July 2010 : Column 1278". Hansard. Houses of Parliament. 27 July 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Archbishop makes Zimbabwe protest". BBC News. 9 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Archbishop urges Mugabe overthrow". BBC News. 6 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ "Archbishop ends 10-year Mugabe protest". BBC News. 26 November 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Archbishops attack City practices". BBC News. 25 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Archbishop of York condemns Ugandan anti-gay bill Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- ^ "Cambridge Accord (with UK signatories and refusals to sign)". Archived from the original on 19 February 2002. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Beckford, Martin (27 January 2012). "Don't legalise gay marriage, Archbishop of York Dr John Sentamu warns David Cameron". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Sentamu, John (17 May 2012). "A Response on Marriage and Civil Partnerships". archbishopofyork.org.

- ^ "I would "never" describe homosexuality as a sin – Archbishop John Sentamu". UG Christian News. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Archbishop John Sentamu: Homosexuality is not a sin, LGBT people were created in God's image too". PinkNews. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Church of England bishops call for ban on gay conversion therapy". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Church of England backs special services marking new identities for transgender people". Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Archbishop backs William and Kate's decision to live together before marriage". The Telegraph. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill". Press release containing text of speech. Archbishop of York's press office. 19 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ "Easter egg row: Church of England accuses National Trust of 'airbrushing' religion out of children's egg hunt". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ a b Walker, Tim (28 February 2012). "John Sentamu's Sunday service may be short". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "We must have faith for Maddie". Press release of article originally written for The Sun newspaper. Archbishop of York's press office. 4 July 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ "Archbishop leads outdoor baptisms". BBC News. 23 March 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ "Archbishop skydives for soldiers". BBC News. 6 June 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Paras recognise Dr John's pluck". The Press. Newsquest Media Group. 21 February 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ Beckford, Martin (6 June 2008). "Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, performs skydive". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Senior Anglican clergy accused of failing to act on rape allegations". The Guardian. 26 July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Goddard Inquiry begins to sift through Church's evidence". Church Times. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Sex abuse survivors protest outside Christ Church enthronement and accuse bishop of ignoring rape claims". The Oxford Times. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Police investigate archbishop for 'failures' over child abuse claims". The Times. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Police look at bishops' 'failure to act' over sex abuse claims". BBC. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Sentamu ordered 'no action' against paedophile priest – leaving him to abuse again and commit suicide". Archbishop Cranmer. 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Archbishop of York facing police investigation over failure to report abuse". Christian Today. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "The Guardian view of abuse in the church: a truly dreadful story". The Guardian. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Call for the Resignation of Archbishop John Sentamu and Bishop Steven Croft". Thinking Anglicans. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Former Archbishop told to step down". BBC. 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1949 births

- Living people

- Archbishops of York

- British people of Ugandan descent

- Bishops of Birmingham

- English people of Ugandan descent

- Bishops of Stepney

- Lords Spiritual

- 20th-century Church of England bishops

- 21st-century Anglican archbishops

- Alumni of Selwyn College, Cambridge

- Alumni of Ridley Hall, Cambridge

- Fellows of Selwyn College, Cambridge

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People associated with York St John University

- People associated with the University of Cumbria

- People from Kampala

- Ugandan Anglicans

- Makerere University alumni

- Ugandan emigrants to the United Kingdom

- British Anglicans

- Black British religious leaders

- The Sun (United Kingdom) people

- Ordained peers

- Critics of multiculturalism

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- Crossbench life peers