Bar (heraldry)

In English heraldry, the bar is an heraldic ordinary consisting of a horizontal band extending across the shield.[1] In form, it closely resembles the fess but differs in breadth: the bar occupies one-fifth of the breadth of the field of the escutcheon (or flag);[2] the fess occupies one-third.[3] Heraldists differ in how they class the bar in relation to the fess. A number of authors consider the bar to be a diminutive of the fess.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] But, others, including Leigh (1597) and Guillim (1638), assert that the bar is a separate and distinct ‘honorouble ordinary’.[11][12][13][14][15] Holme (1688) is equivocal.[16] When taken as an honourable ordinary, it is co-equal with the other nine of the English system.[17] Some authors who consider the bar a diminutive of the fess class it as a subordinary.[18][19] Authorities agree that the bar and its diminutives have a number of features that distinguish them from the fess.

The diminutive of the bar one-half its breadth is the closet, while the diminutive one-quarter its breadth is the barrulet.[20] These frequently appear in pairs separated by the width of a single barrulet. Such a pair is termed a bar gemel and is considered a single charge and a third diminutive of the bar.[21] A field divided by many bars — often six, eight or ten parts with two alternating tinctures — is described as barry. The term bar is also sometimes used as a more general term for ordinaries that traverse the field and sometimes to denote the bend sinister and its diminutives.[22]

A horizontal partition of the field at the base, occupying the breadth of a bar, is termed a base-bar (or baste-bar).[23][24][25] This division of the field is also sometimes termed a base (also baste) or a point or plain point.[26][27][28][29][30][31] It has also been referred to as a base point, point in base, party per baste bar (or party in baste bar).[32][33][34][35] It has even been termed simply a bar and its position at the base noted.[36] Some authors hold that this bearing is an abatement, or mark of dishonor, if of the tincture sanguine (or perhaps tenné).[37][38][39][40] If sanguine, it is held to be a mark of dishonor for the offense of lying to the sovereign.[41][42] Newton (1846) elaborates even further and ascribes it to the offense of 'fabricating false intelligence, thereby misleading a commander and placing the army in danger'.[43] However, Berry (1828) stresses that, if of one of the many other metals or colours, it is a badge "of the greatest honor and distinction".[44]

Like other charges, bars (and base-bars) may bear varied lines—such as embattled, indented, nebuly, etc.[45]

Differences between bar and fess

[edit]There are several differences between the bar and the fess, in addition to their difference in breadth. An escutcheon or flag can bear only one fess but multiple bars.[46][47][48] Also, the fess must remain centered along the line extending from the exact middle of the escutcheon or flag, while the bar can be borne “in several parts of the field”.[49][50][51][52][53] However, Guillim asserts that the if there is a single bar it must assume the place of the fess at the center of the field.[54] Some textbooks state that the bar cannot be borne singly,[55] but this is erroneous.[56] Smedley et al. (1845) maintain that if there are two bars, they must be placed equally distant from the fess point or center of the shield, the space of a bar between them, effectively dividing the field into five equal parts.[57][58] (Neither convention is strictly observed in vexillography.) Further, for those that maintain that the bar is an honourable ordinary separate and distinct from the fess, the fess is distinguished among the ordinaries in that it has no diminutives.[59] The bar is universally held to have two diminutives: the closet and the barrulet.[60][61][62][63][64][65]

Symbolism

[edit]Another key difference between the bar and fess is the significance of what they each represent. For Nisbet (1722), the bar represents “a piece wood or other matter” laid across a pass, bridge, or gate to bar passage to an enemy.[66] As such, the bar on a shield or an escutcheon represents to the bearer "force, valour, courage, or wisdom, whereby he hath repelled any peril or danger imminent to his country or sovereign".[67][68][69] Nisbet, citing Ferne (1586), observes also that the diminutives of the chevron, bend, and pale—the chevronel, bendlet, and pallet—represent pieces of wood or other matter used as different parts of fortified barriers surrounding settlements or encampments.[70] The honourable ordinary the pale is also said to represent a wooden stake or picket used as a part of such a defensive barriers.[71] The term closet may derive from the Latin claustrum and signify a bar used to secure a door or gate shut.[72] The fess on the other hand portrays the military arming belt or Girdle of Honor awarded by rulers to soldiers or warriors for special services performed, as part of the ceremony of their investiture as knights.[73][74] The fess is thus symbolic of military rank, achievement, recognition, and distinction.

Other uses of term

[edit]The term bar has sometimes been used in a heraldic context to denote other charges. Mackenzie (1680) observed that in the Scots heraldry of the day, the term bar was used for what the English termed the fess.[75] Ferne (1586) used the expression 'bar in base'[76] for a diminutive of the champagne or base. Nisbet (1722) found that the term ‘bar’ had been used “by all nations” as a general term for all pieces that “thwart or traverse” the field, as many of the honourable ordinaries do.[77] The Spanish have used the term “indifferently” for pales, fesses, and bends.[78] For example, the arms of Aragon and Barcelona—Paly argent and gules—are termed by them Barras longas, and Nisbet claims this usage is at the root of the place-name Barcelona.[79][nb 1] They observe that the Italians also have used the term sbarra (pl. sbarre) similarly.[83] Ginanni (1756) declares this usage mistaken though, and that the term sbarra properly refers to the bend sinister.[84]

In French heraldry, the term barre is also specifically used to denote the English bend sinister.[85] Writing of Scots heraldry in English, Nisbet himself uses the term ‘bar’ for the bend sinister.[86] The term ‘bar sinister’, derived from the French usage of barre, has sometimes been used in English to denote the bend sinister as a "brisure of illegitimacy".[87] It has even been referred to as the ‘bastard bar’.[88] The baton sinister, also taken as a mark of illegitimacy, has been referred to as the ‘Bar of bastardy’[89] and the 'Fillet of bastardy'.[90] Though commonly used, this adaptation of the French use of 'bar' into English it involves has been harshly criticized by some heraldists. The term ‘bar sinister’ has been dismissed as an “ignorant vulgarism”[91] and “an absurdity and impossibility”[92] in light of the established English usage of bar.

In contemporary vexillology, one also sometimes encounters a general or ‘indifferent’ use of the term bar. Alfred Znamierowski (2007) refers to the white fess of the Flag of Austria as a “wide bar”, and then also immediately characterizes its design as "white-red-white stripes".[93] The First National Flag of the Confederate States of America (1861-1863) has been popularly nicknamed the "Stars and Bars". The field of this flag is, like the Flag of Austria, composed of a white fess on a red field.

Diminutives

[edit]The bar has four diminutives: the closet, barrulet, bar gemel, and cottise. The diminutive half its width is the closet, and that one-fourth the width is the barrulet.[94][95] Barrulets are often borne in pairs known as bar gemel, the pair separated by the width of a barrulet and considered a single charge. A coat of arms can bear multiple bar gemels, though four is usually the maximum.[96] The bar gemel is sometimes referred to by the French Jumelle or jumelles.[97][98] One or several barrulets can be borne on the field separately as well, however.[99] The diminutive of the barrulet, half its width, is known as a cottise. Cottises rarely appear alone, but are most often borne on each side of an ordinary (such as a fess, pale, bend or chevron). The ordinary thus accompanied by a cottise on each side is then described as "cottised", or these may even be "doubly cottised" (i.e. surrounded by four cottises, two along each side).[100] A single cottise is usually blazoned a cost.[101][102]

A bar that has been "couped" (cut) at the ends so as not to reach the edges of the field is called a hamade, hamaide or hummet, after the town of La Hamaide in Hainaut, Belgium.[103] As a charge, it is almost always depicted in threes. The adjective is hummety.[104]

-

three bars

-

a closet

-

two barrulets

-

a bar gemel

-

three bars gemelles

-

a fess doubly cottised

-

three hamades

French diminutives of the fess

[edit]French heraldry has a set of diminutives of the fess—the fasce en divise, trangle, burelle, and filet—that a number of writers treat as equivalent to the English bar and its diminutives.[105][106][107] In French heraldry, the bar as defined by the English is "unknown",[108] but Boyer (1729) writes that the English bar "answers to" the French fasce on divise, while the English barrulet "agrees pretty nearly" to the French burelle.[109] However, these French diminutives of the fess are defined differently than the English bar and its diminutives—in terms of the proportion of their breadth relative to that of the field and to each other. The fess (Fr. fasce) occupies one third of the breadth of the field and the fasce en divise, burelle/trangle, and filet are defined as one half, one-third, and one-fourth the breadth of the fess, respectively, or one-sixth, one-ninth, and one-twelfth the breadth of the field.[110] (Regarding the trangle, French usage is not consistent, but it is often defined as a component of the variation of the field field burellé (Eng. barry) when its transverse pieces are odd in number, i.e. as the equivalent of the burelle.[111][112]) The English bar, on the other hand, is defined as one-fifth the breadth of the field, and its diminutives—the closet, barrulet, and cottise—are defined as one half, one quarter, and one-eighth the breadth of the bar, or one-tenth, one-twentieth, and one-fortieth of the field. The bar and fasce en divise are roughly approximate as one-fifth and one-sixth of the field, respectively. But the burelle and barrulet are quite different—one-ninth and one-twentieth of the field. The English closet (one-tenth) does however approximate the burelle (one-ninth).[113] The French filet (one-twelfth) is not far either.

The tierce is a charge composed of three diminutives of the fess that are one-fifth its breadth and separated by an equal space, together occupying the breadth of a fess (one-third of the field).[114][115] The charge is analogous to the bar gemel as a pair of diminutives of the bar separated by a space equal to their width. As such, the tierce can be considered a diminutive of the fess. (If the charge is oriented bend-wise, the name tierce is still applied, its component diminutives referred to as bendlets.[116]) It can be noted that the diminutives composing this charge, as one-fifteenth the breadth of the field, are the same breadth as those composing the bar gemel as a diminutive of the bar (i.e. also one-fifteenth). Boyer's (1729) use of the term 'barrulet' to refer to the diminutives composing this charge is an example of how in practical use terms like barrulet are employed flexibly (for a diminutive one-third the breadth of the bar in this instance).

Finally, a word of caution is in order concerning the French term divise or fasce en divise when used for a diminutive of the fess said to be equivalent to the English bar. It risks confusion with the more prevalent French heraldic use of the term divise (sometimes fasce en divise) to denote a diminutive of the fess roughly the breadth of the filet. This divise (also filet en chef)[117] "supports" the chief, being positioned at its bottom edge and functioning effectively as fimbriation (see fillet).[118][119][120]

-

a fasce (fess) en divise

-

a burelle / trangle

-

a filet

-

a tierce

Barry, barruly, bars

[edit]Barry is the term applied to a field that is divided by parallel lines into numerous horizontally transverse partitions of equal breadth, and that alternate in tincture.[121] The tinctures are often two in number, and specified as an alternating color and metal, but sometimes can be more than two in number.[122][123][124] Many heraldic traditions reserve the term barry for fields with partitions of an equal number.[125] The number of partitions is typically specified as six or more and the transverse sections are termed bars.[126][127] (The French use the term 'fessy' (fascé) for partitions up to five.) The term bars is applied even though only a field of five partitions would be composed of English bars strictly speaking.[128] In blazoning fields as barry, the term bar is thus used flexibly by heraldists. Barry of six is common[129] and Ferne suggests that the close resemblance of these partitions of the field to the bar, strictly defined, means that this variation of the field expresses the same meaning as the bar: force, valor, courage and wisdom and having repelled "any danger or peril imminent to country or sovereign".[130]

In English heraldry, if the partitions are odd in number, they are not blazoned as barry. Instead, they are blazoned as a certain number of bars upon a field—a field of the tincture of the more numerous partitions, charged by bars of the number and tincture of the fewer.[131] Thus a field with eight transverse sections alternating red and gold would be blazoned as barry of eight, or and gules, while a field with nine horizontal transverse sections alternating red and gold would be blazoned as Gules, four bars or. However, not every heraldic tradition is said to strictly observes the convention of not blazoning an odd number of transverse partitions as barry. Some English sources suggest that the French and other nations are “not so nice”[132] or "not as particular"[133] in their observance of the convention. However, French language heraldic sources seem to indicate that French heraldists do commonly observe the convention.[134][135] At the same time, Woodward, citing examples in French and German heraldry, asserts that even in English it is correct to blazon an odd number of partitions as barry—but in specific cases.[136] It is correct if refers to an odd-numbered partition varied by an odd number of tinctures—such as nine partitions of three repeating tinctures—or if an odd number of partitions are colored by the same number of tinctures, one for each transverse section.[137][138]

If the partitions number twelve or more, the field is not blazoned as barry but as barruly.[139] However, in French, the term for barry is burellé and the sections are termed burelles, a diminutive of the fess one-third its breadth.[140] Although, as in English the term is applied flexibly for a range of numbers of constituent partitions and consequent breadths. The English terms barrulet and barruly recall the French terms burelle and burellé; but they are not cognate. Burelle may be analogous to the English bar in some cases and barrulet in others; but burellé is analogous to English barry.

Barry compound terms

[edit]The term barry is sometimes compounded with other heraldic terms and this is done for one of three reasons: to indicate the modification by horizontally transverse partitions by variations of line, to indicate complex partitions with additional orthogonal lines of division, and the use of charges other than bars placed horizontally and transversely (barways) to effect variations of the field.

Barry and variations of line

[edit]First, a barry-compound term can be used to indicate that the horizontal lines of partition dividing the field are modified by heraldic variations of line. Barry-wavy, barry-nebuly, and barry-dancetty are commonly cited examples.[141][142]

Barry-wavy

[edit]The wavy variation of line and barry-wavy variation of the field generally represent water.[143] The heraldic mobile charge fountain takes the form of a heraldic roundel barry-wavy of six, argent and azure (white and blue). The charge represents a well or spring, and Berry (1810) speculates that the fountain "might have been borne by ancient knights to express the inexhaustible source of courage ever to be found within them, which flowed from motives equally pure as the crystal stream."[144] Guillim (1679) suggests that wavy lines of variation may evoke triumph over adversity and steadfastness in the face of the 'stormy seas' of fate.[145] Nisbet (1722) finds that, in their time, barry-wavy arms were granted in recognition of services performed for country and sovereign at sea.[146]

Barry-nebuly

[edit]Nebuly on the other hand is an undulating line of variation and division symbolizing clouds.[147] Du Marte (1777) suggests that it may symbolize an award of arms for skill in navigation, in recognition of an achievement requiring the mastery of "storms, clouds, and wind".[148] As with other barry variations of the field, the number of partitions is specified in blazonry (barry of six, barry of eight, etc.). But, often it is not specified whether the parallel lines of barry-nebuly vary in synchrony or counter-vary and that can pose difficuries for translating from blazon to visual representation.[149]

Barry-dancetty and bars indented

[edit]Finally, the line dancetty (dancette, dancetté) is another variation of line used to modify the lines of barry variations. A line dancetty is a line drawn zig-zag, resembling the teeth of a saw.[150] It is often defined as a larger variant of a line indented, with the number of 'teeth' limited to three.[151][152] A dancetty line may be used represent water (in the same way the wavy line does).[153] As noted, the indented variation of line closely resembles the dancetty, having only a greater number of consequently smaller, narrower and shallower 'serrated' or 'tooth-like' protrusions.[154] But they have divergent meanings: the indented line symbolizes fire rather than water.[155] Additionally, the term barry-indented is used in a very different manner than barry dancetty as well. Instead of barways lines running parallel, it refers to the type of complex patterns of variation effected by the intersection of multiple lines of division: in this case, barry and indented lines intersecting to produce a pattern of triangles, counter-changed.[156] Complex patterns of this type, including barry-indented, are discussed in the next section.

Barry and additional lines of partition

[edit]The second use of barry in compound terms is to express that the horizontal lines of division partitioning the field as barry are crosscut by one or more non-horizontal lines of partition. These complex patterns of shapes are marked by counterchanging of tinctures that produces more complex patterns of variation composed by horizontal arrays of various shapes. Barry-lozengy, barry-indented, and barry-paly are prominent examples. These variants are sometimes named by the lines of division producing them (bendy, paly, chevronny, fretty), sometimes by the counterchanging shapes produced (lozengy, trianglé) and sometimes by both (barry-bendy-lozengy).[157][158]

Barry-bendy

[edit]Barry-bendy is a pattern of variation produced by the intersection of a barways partition of the field and a bendy one. The resulting shapes produced by counter-changing are lozenges whose long edges run parallel to the top and bottom of the shield or flag. (Similar lozenges with long axes oriented vertically are produced by the combination of paly and bendy lines, i.e. a paly-bendy or bendy-paly variation.[159]) The bendy lines of division of barry-bendy may be bendwise or counter-bendwise.[160][161] Barry-bendy is also sometimes referred to as barry-lozengy.[162][163] This pattern of variation resembles the other lozengy and fusilly patterns that are not barry as they are not formed by barwise lines of partition. These non-barry patterns are produced by the intersection of bendy and counter-bendy lines.[164] If the angle of the two lines of division are the same they are blazoned as and the long axis is vertical, simply lozengy or fusilly (a more elongated lozenge), but if horizontal as in fess or in bar.[165] If the bendy and counter-bendy lines of partition are not at the same angle, the lozengy or fusilly variation can be 'tilted' bendwise or counter-bendwise and are blazoned as in bend or in counter-bend.[166] Examples of these are the fusilly of the arms of the Grimaldi family as Sovereign-Princes of Monaco[167][168] and the lozengy or fusilly in bend of Arms of the Elector of Bavaria and the Duke of Teck.[169][170] Smedley et al. (1845) hold that if the intersection of bendy and bendy-sinister lines of division produces lozenges or fusils whose long axis is oriented barwise, it can be blazoned fusilly barry.[171]

Barry-indented

[edit]The barry-indented is a pattern of triangle shapes counter-changed that has been conceived in a number of ways: by some as produced by the intersection of three variations of the field: barry, bendy and counter-bendy (or barry and bendy dexter and sinister);[172][173] by others, as noted above, as produced by the intersection of barry and indented lines;[174] and, finally as a lozengy pattern couped and counter-changed per fess or bar.[175] These diverse conceptions have led to a proliferation of an even greater number of alternate names: barry point in point[176] triangle counter-triangle,[177][178] just counter-triangle,[179] lozengy couped per fess,[180] trianglé,[181] barry bendy sinister and dexter,[182] and barry-bendy-lozengy.[183] At the same time, it is not common. An extant example of this pattern is the banner of the commune of Sant'Ambrogio di Valpolicella in Veneto, Italy. A special case of this type of variation in blazonry, one composed of four bars intersected by both bendy and counter-bendy variations, has another name—barry per fret.[184]

Barry-paly

[edit]Barry-paly is when a barry variation of the field is counter-changed per a paly variation of the field, that is by vertical transverse sections of equal width.[185] When a barry variation is counter-changed per a single perpendicular line, this is known as barry per pale counter-changed instead.[186] If the width of the sections produced by lines of the paly division of the field is equal to the breadth of the transverse sections of the barry division of the field, this special case of a barry-paly variation of the field is known as chequy.[187]

In addition to compound barry terms, conjunctive expressions ‘barry and per (charge)’ or ‘barry and (variation)’ or 'fess per and per (charge)' have also sometimes been used to evoke these complex patterns of variation.[188][189] What could be termed barry-chevronny or 'barry and chevronny (of six)', "ancient authors"[190] would blazon as "chevron per and per fess, of six".[191] In such a formula, the numerical operator "of six" operates on both terms—'barry of six' and 'chevronny of six'. On the other hand, if the numerical operator is not appended, say as in "chevron per and fess" the field is divided and counter-changed by only a single line per chevron and a single line per fess.[192] A field barry per canton or barry per chevron is similarly divided (see, for example, the Flag of the Orange Free State as barry per canton, counterchanged).

Other variations of the field, such as vair and potenty, feature the barways distribution of various shapes but are not considered barry.

-

Barry of eight

-

Barry of eight, per pale counterchanged

-

Barry of eight, per bend counterchanged

-

Barry-bendy

-

Barry-bendy sinister

-

Barry-indented

-

Barry-paly as Chequy

Barways placement of other charges

[edit]Finally, the third reason the term barry is compounded with other heraldic terms is to indicate that a field is divided into partitions of alternating tinctures by the horizontal placement, barways, of equal-breadth charges other than bars that traverse the field.

Barry-pily

[edit]Barry-pily (Fr. emanché [193]), a field divided by the barways placement of piles throughout of equal breadth, is a commonly cited example of the third type of barry variation.[194][195][196] Like other barry variations, it can be blazoned as of so many pieces, the number corresponding to the sum of partitions of both or all its alternating tinctures.[197] Gough and Parker (1894) maintain that if the number of transverse barwise piles is odd, it should not blazoned as barry-pily, but as so many piles (throughout) barwise.[198] However, if Guillim (1638) is followed any number of piles throughout will produce an even number of partitions of alternating tincture and can be blazoned as barry-pily.

Barways, barwise, in bar

[edit]The terms barways and barwise are used to denote either the orientation (direction) or arrangement (placement, positioning, situation) of charges, specifically along a horizontal line parallel to the top edge of the field of the shield, escutcheon, or flag. Barways and barwise are synonyms that can be used interchangeably to refer to a horizontal orientation or arrangement.[199] In some cases, the term barways/barwise can denote both a horizontal orientation and arrangement of particular charges.[200] The term ‘in bar’ denotes only the arrangement of multiple charges along a horizontal line.[201][202][203][204][205] Charges blazoned as barways/barwise or in bar are ‘common’ or ‘mobile’ charges. Both the placement upon the field and orientation of such charges can vary, in contrast ‘honourable ordinaries’ or ‘proper charges’. As noted above, the expression barways (or barwise) is also used to describe the horizontal orientation of the lines of division used to produce the barry variation of the field.[206][207][208][209] Relatedly, Elvin (1889) even uses the expression triparted barwise for what others term tierced in fess.[210][211]

When applied to charges, the first of two uses of barways/barwise is to describe the orientation of charges. It denotes a horizontal orientation of a charge or charges that could also be oriented vertically (palewise) or diagonally (bendwise or counter bendwise).[212][213][214] These charges are typically oblong—they have one axis longer than the other and the orientation described is the alignment of their long axis, along a horizontal line.[215][216] These charges are sometimes of such length that only one can be arranged along a given horizontal line traversing the field. They are said to be ‘athwart the field’.[217] If more than one such charge is borne upon the field of a shield (or flag) they are arranged vertically centered along a single (paleways) line, i.e. they are stacked one upon the other.[218][219][220] They are blazoned as ‘barways/barwise’ in reference to their orientation, with their palewise arrangement often implicit.[221] Sometimes, however, they are blazoned as in pale barways[222] or barways in pale.[223][224] Examples of multiple charges blazoned barways/barwise in this sense include battering rams;[225][226][227] bladed weapons such as swords,[228][229][230] including the seaxes of Essex;[231] agricultural implements such as rakes[232] or scythes,[233] and animals or parts of animals.[234][235]

The second use of barways/barwise is to denote the arrangement (placement or positioning) of two or more charges,[236] often of the same type,[237] along one or more horizontal lines.[238] The expression in bar is used synonymously with this second use of barways/barwise.[239][240] To be blazoned as ‘in bar’ or ‘barwise’/barways (in this second sense), the charges must be arranged along a line or lines above or below or center (fess point) of the field.[241][242] Some authors stipulate that there must be two or more rows of charges arranged upon such lines.[243][244] Charges capable of being arranged ‘in bar’ are relatively small.[245] If charges are arranged along a single horizontal line running through the center-point of the field they are not blazoned as in bar, but instead as in fess.[246][247] If multiple charges are arranged along a line running through the middle of the chief, they are often blazoned not as ‘in bar’ but as ‘in chief’.[248] This is consistent with the idea that a bar cannot be placed in chief.[249] It also corresponds to the heraldic convention regarding the use of terms like barways/barwise and in bar—that they are to be used when charges depart from the default placement of that number of charges in that region of the field.[250] Barways/barwise is the typical placement of two or more charges in the chief. It is not of charges in base. The default placement of three charges on the field is two and one—two in the upper part of the field and one in the lower.[251] If multiple charges are positioned along a line running though the base (champagne), they are blazoned as ‘barwise in base’ or ‘in base barwise’.[252] If they are oriented barways as well as arranged in that manner, the term barways addresses both aspects.[253]

Finally, not every author treats the terms barways/barwise and in bar as synonymous. Nisbet (1722) reserves the use of barways/barwise for the first use—the horizontal orientation of one or more typically oblong charges—and ‘in bar’ for the second use—the arrangement of multiple charges along one or more horizontal lines[254] Other authors however use the expression barways/barwise for both the orientation of oblong charges and the arrangement of multiple charges.[255][256]

Practical use of terms

[edit]In practical use, the number and breadth of narrower fess-like and bar-like charges placed on a field varies. When used to create variations of field of equal-breadth horizontal partitions, the number can range continuously from four to twelve (or more). That is, such charges are devised without regard to the number that would correspond to the abstract definition of the breadth of the bar and its diminutives—the closet and barrulet—or the French fess en divise and other French diminutives of the fess—the burelle/trangle and the filet. Some heraldists, therefore, question the usefulness of these terms. Copinger (1910) reports that Joseph Edmondson dismissed them as “useless and superfluous in blazon” because heraldists tended to use the term bar as a covering term for its diminutives and charges that approximate them without regard to their number or precise breadth.[257] Outside the precision of blazon, some heraldists have nonetheless found it advantageous at least to have term barrulet that they employ flexibly—sometimes to describe partitions a third the width of a bar or less, or sometimes a quarter of a fess. Vexillologists often employ the terms 'stripe' or 'bar' indiscriminately for horizontally or vertically transverse charges or partitions composed of parallel lines, even sometimes for honourable ordinaries such as the fess, pale, chief, champagne, or sides.[258][259][260]

Examples

[edit]-

Argent, five bars dancetty azure, Arms of the Tocco family

-

Gules, four bars indented Or, Arms of the Dujac family (Bayonne)

-

A bar gemel wavy cottised in the arms of the French commune of Berneuil-sur-Aisne

-

Barry of ten sable and Or in the arms of the German state of Saxony

-

A bordure barry of ten argent and sable

-

Arms of Richard de Valoines: Barruly of 14 argent and azure on a bend gules three mullets of six points or (1285)

-

Coat of arms of Avermes, Allier department, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, France: Argent, three bars sable, a bend, counterchanged

-

Lion barry of ten argent and gules in the arms of the German state of Hesse

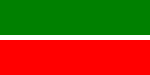

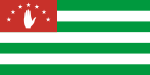

On flags

[edit]Bar

[edit]-

Municipal Flag of Bandung, Indonesia

-

Flag of Labrador (unofficial), Canada

-

Flag of the New York City Police Department

-

Flag of Ehime Prefecture, Japan

Fess en divise

[edit]Other bar

[edit]-

Flag of Israel

(5/32s field) -

Flag of Transnistria

(1/4 field) -

Flag of the former Russian-American Company

-

Flag of the Republic of Colombia

(1/4 field) -

Flag of the Republic of Ecuador

(1/4 field) -

Flag of Rwanda

(1/4 field) -

Flag of Mauritius

(1/4 field) -

Flag of the Central African Republic

(1/4 field) -

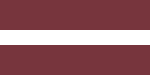

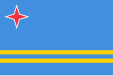

Flag of the Comoros

(1/4 field) -

Flag of Afghanistan

(former, 1974–1978, 1/4 field) -

Flag of Zimbabwe

(1/7th field) -

Merchant ensign of the former French Algeria (1848–1910)

(1/7th field) -

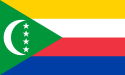

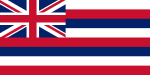

Flag of Hawaii

(1/8th field)

Diminutives

[edit]-

Former flag of the Arab Maghreb Union

(closet) -

Flag of the provisional People's Republic of Korea (three closets as tierce-like charge)

Barry, barruly, bars

[edit]Barry compound terms

[edit]-

Flag of the Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

(A bend, barry-indented counterchanged) -

Flag of Bremen, Germany

(Barry of eight gules and argent, a side barry-paly as chequy gules and argent) -

Flag of Guernsey, British Islands (former, 19th Century)

(Three cantons barry-paly as chequy argent and azure) -

Flag of the Orange Free State

(Argent, three bars orange, per canton counterchanged gules, argent, and azure)

Non-barry lozengy and fusilly variations

[edit]-

Flag of Monaco (variant)

(fusilly) -

Flag of the Supreme Court of Canada

(lozengy)

Other non-barry variations

[edit]Barways, barwise, in bar

[edit]-

Flag of Saudi Arabia

(barways/barwise) -

Flag of Uzbekistan

(in bar)

Non-barways (barwise, in bar) arrangements

[edit]See also

[edit]Fess

Fillet (heraldry)

Ordinary (heraldry)

Charge (heraldry)

Fimbriation

Liste de pièces héraldiques

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Guillim, John (1638). A display of heraldry : manifesting a more easie access to the knowledge thereof than hath been hitherto published by any, through the benefit of method (Third ed.). London: Jacob Blome. p. 80. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Leigh, Gerard (1597). The accedence of armorie. London: Printed by Henrie Ballard ... p. 67. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ Berry, William (1828). Encyclopaedia heraldica; or, Complete dictionary of heraldry, Volume 1. London: Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper. p. BAN-BAR. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Nisbet, Alexander (1722). A System of Heraldry, Speculative and Practical: with the True Art of Blazon ... Illustrated with Suitable Examples of Armorial Figures, and Achievements of the Most Considerable Surnames and Families in Scotland. Edinburgh: J. Mack Euen. pp. 59–60. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Robson, Thomas (1830). The British Herald; Or, Cabinet of Armorial Bearings of the Nobility & Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, from the Earliest to the Present Time: With a Complete Glossary of Heraldic Terms: to which is Prefixed a History of Heraldry, Collected and Arranged ... Vol. III. Sunderland: Thomas Robson. p. BAN-BAR. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Baigent, Francis Joseph; Russell, Charles James (1864). A practical manual of heraldry and of heraldic illumination : with a glossary of the principal terms used in heraldry. London: George Rowney and Co. p. 7. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Woodward, John (1896). A Treatise on Heraldry, British and Foreign: With English and French Glossaries, Volume 1 (New ed.). Edinburgh and London: W. & A.K. Johnston. p. 136. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Cussans, John Edwin (1893). Handbook of Heraldry: With Instructions for Tracing Pedigrees and Deciphering Ancient Mss., Rules for the Appointment of Liveries, &c (Fourth ed.). Chatto & Windus. p. 58. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Rothery, Guy Cadogan (1915). A.B.C. of Heraldry. London: Stanley Paul & Co. p. 4. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Leigh (1597), p. 67

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ du Marte, Antoine Pyron; Porny, Mark Anthony (1777). The Elements of Heraldry: Containing the Definition, Origin, and Historical Account of that Ancient, Useful, and Entertaining Science... (Third ed.). London: T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Junior. p. 74. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Gough, Henry (1847). A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. Oxford and London: J. Parker and Co. p. 43.

- ^ Grant, Sir Francis James (1846). The Manual of Heraldry. London: Jeremiah How. pp. 21–22. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Holme, Randle (1688). The academy of armory, or, A storehouse of armory and blazon containing the several variety of created beings, and how born in coats of arms, both foreign and domestick : with the instruments used in all trades and sciences, together with their terms of art : also the etymologies, definitions, and historical observations on the same, explicated and explained according to our modern language : very usefel [sic] for all gentlemen, scholars, divines, and all such as desire any knowledge in arts and sciences. Chester: Printed for the Author. p. 36. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Seton, George (1863). The Law and Practice of Heraldry in Scotland. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. p. 455. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. ix

- ^ Elvin, Charles Norton (1889). A dictionary of heraldry : with upwards of two thousand five hundred illustrations. London: Kent and Co. p. 12. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London and Edinburgh: T. C. & E. C. Jack. p. 119.

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAS–BAS

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 14

- ^ Pimbley, Arthur Francis (1908). Pimbley's Dictionary of Heraldry: Together with an Illustrated Supplement. Baltimore: The author. p. 10. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAS–BAS

- ^ Holme (1688), p. 71

- ^ Edmondson, Joseph (1780). A Complete Body of Heraldry, Vol. II. London: Printed for the author by T. Spilsbury. p. PIL-PRE. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Newton, W. (1846). A Display of Heraldry. London: W. Pickering. p. 392. OCLC 930523423.

- ^ Millington, Ellen J. (1858). Heraldry in History, Poetry, and Romance. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 399. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 102

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAS–BAS

- ^ Ferne, John (1586). The Blazon of Gentrie: : Deuided into two parts. The first named The Glorie of Generositie. The second, Lacyes Nobilitie. Comprehending discourses of Armes and of Gentry. Wherein is treated of the beginning, parts and degrees of Gentlenesse, vvith her lawes: Of the Bearing, and Blazon of Cote-armors: Of the Lawes of Armes, and of combats. London. p. 183. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Leigh (1597), p. 80

- ^ Holme (1688), p. 71

- ^ Ferne (1586), pp. 212

- ^ Holme (1688), p. 71

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. ABA–ABA

- ^ Newton (1846), p. 390

- ^ Edmondson (1780), p. PIL-PRE

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. ABA–ABA

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 52

- ^ Newton (1846), p. 392

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. ABA–ABA

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 119

- ^ du Marte & Porny (1777), p. 74

- ^ Grant (1846), p. 22

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 46

- ^ Clark, Hugh; Wormull, Thomas (1788). A Short and Easy Introduction to Heraldry (Sixth ed.). London: G. Kearsly. p. 19. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Grant (1846), pp. 21–22

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 43

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ Holme (1688), p. 36

- ^ Brooke-Little, J.P. (1996). A Heraldic Alphabet. Robson Books. p. 42.

- ^ Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, Vol. V. London: B. Fellowes et al. p. 601. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Leigh (1597), p. 68

- ^ Mackenzie, George (1680). The Science of Herauldry, Treated as a Part of the Civil Law, and Law of Nations:: Wherein Reasons are Given for Its Principles, and Etymologies for Its Harder Terms... Edinburgh: heir of Andrew Anderson. p. 37. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Berry (1828), p. BAN-BAR

- ^ Clark & Wormull (1788), p. 19

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 43

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 80

- ^ du Marte & Porny (1777), p. 74

- ^ Mackenzie (1680), p. 37

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Ferne (1586), pp. 143

- ^ Leigh (1597), p. 80

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 35–36

- ^ Smedley, Rose & Rose (1845), p. 601

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 43

- ^ Smedley, Rose & Rose (1845), p. 601

- ^ Mackenzie (1680), p. 37

- ^ Ferne (1586), pp. 183 & 212

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Michael Dietler; Carolina López-Ruiz (15 October 2009). Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-226-14848-9.

- ^ James Maxwell Anderson (30 June 1988). Ancient languages of the Hispanic peninsula. University Press of America. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8191-6732-3.

- ^ "From Barcino to Barcelona".

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Ginanni, Marco Antonio (1756). L'arte del blasone dichiarata per alfabeto. Venice: presso Guglielmo Zerletti. pp. 145–146. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 59–60

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 133

- ^ Woodward, John; Burnett, George (1892). A Treatise on Heraldry, British and Foreign: With English and French Glossaries, Volume II. Edinburgh and London: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 550. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Rothery (1915), p. 153

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 14

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 61

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 136

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 550

- ^ Znamierowski, Alfred; Slater, Stephen (2007). The world encyclopedia of flags & heraldry: an international history of heraldry and its contemporary uses together with the definitive guide to national flags, banners, standards and ensigns. London: Lorenz Books. pp. 141–142. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Leigh (1597), p. 67

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. CLO–COD

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 120

- ^ Gough, Henry; Parker, James (1894). A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry (New ed.). Oxford and London: J. Parker and Co. p. 173.

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAN–BAR

- ^ Ferne (1586), p. 184

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 113, 123

- ^ Robson (1830), p. COR-COU

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. COR–COT

- ^ "Frasnes-les-Avaing (Municipality, Hainaut Province, Belgium". Flags of the World. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Brooke-Little (1996), p. 112

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAN–BAR

- ^ Coats, James (1725). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Jer. Batley. pp. 34–37. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 136

- ^ Cussans (1893), p. 310

- ^ Boyer, Abel (1729). The Great Theater of Honor and Nobility. London: Henry Woodfall. p. 199. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Boyer (1729), p. 199

- ^ Rietstap, Johannes Baptista (1884). Armorial général: précédé d'un Dictionnaire des termes du blason, Tome I A-K. Gouda: G. B. Van Goor. p. xxx. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 62

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 62

- ^ Boyer (1729), p. 193

- ^ Gheusi, Pierre-Barthélemy (1892). Le blason héraldique: Manuel nouveau de l'art héraldique de la science du blason et de la polychromie féodale d'après les règles du moyen age avec 1300 gravures et un armorial. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot et c. p. 56.

- ^ Boyer (1729), p. 193

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 473

- ^ Plomteaux, Clément; Agasse, Henri (1784). Encyclopédie méthodique: Histoire, Tome premier. Paris and Liège: chez Panckoucke et chez Plomteaux. p. 53. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Migne, Jacques-Paul (1852). Encyclopédie théologique: ou, Série de dictionnaires sur toutes les parties de la science religieuse... Tome Treizième: Dictionnaire Héraldique. Paris: Ateliers Catholiques. p. 261. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ de Mailhol, Dayre (1895). Dictionnaire historique et héraldique de la noblesse française. Paris: Impr. Ch. Lépice. p. 90.

- ^ Robson, Joseph (1780). A complete body of heraldry : containing, an historical enquiry into the origin of armories, and the rise and progress of heraldry, considered as a science ..., Vol. II. London: Printed for the author by T. Spilsbury. p. BAR-BEL. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ de Foras, Amédée (1883). Le blason: dictionnaire et remarques. Grenoble: Joseph Allier. p. 63-64. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Copinger, Walter Arthur (1910). Heraldry Simplified: An Easy Introduction to the Science and a Complete Body of Armory, Including the Arts of Blazoning and Marshalling, with Full Directions for the Making of Pedigrees and Information as to Records &c. Manchester: The University Press. p. 329. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Boyer (1729), pp. 192–3

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 373

- ^ du Marte & Porny (1777), p. 74

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 52

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 52

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 106

- ^ Ferne (1586), p. 143

- ^ Cussans (1893), p. 77

- ^ Coats (1725), p. 35

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAR–BAR

- ^ Boyer (1729), pp. 192–3

- ^ de Foras (1883), pp. 63–64

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 105

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 105

- ^ de Foras (1883), pp. 63–64

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 120

- ^ Boyer (1729), pp. 192–3

- ^ Edmondson (1780), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Robson (1830), pp. BAR–BAS

- ^ Gough (1847), pp. 322 & 323

- ^ Berry, William (1810). An Introduction to Heraldry: Containing the Rudiments of the Science in General, and Other Necessary Particulars Connected with the Subject. London: T. Egerton. p. 62. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Guillim, John (1679). A display of heraldry : manifesting a more easie access to the knowledge thereof than hath been hitherto published by any, through the benefit of method (Fifth ed.). London: Printed by S. Roycroft for R. Blome, and are sold by Francis Tyton, Henry Brome, Thomas Basset, Richard Chiswell, John Wright, and Thomas Sawbridge. p. 67. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 22

- ^ Grant (1846), p. 101

- ^ du Marte & Porny (1777), p. NE-NO

- ^ Whitmore, William Henry; Appleton, William Sumner (1867). The Heraldic Journal: Recording the Armorial Bearings and Genealogies of American Families, Vol. III. Boston: Wiggin & Lunt, Publishers. pp. 144–145. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Edmondson (1780), p. CRO-DIA

- ^ Clark, Hugh; Wormull, Thomas (1776). A Short and Easy Introduction to Heraldry, wherein its most useful terms are displayed, etc. London: G. Kearsly. p. 20. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ du Marte & Porny (1777), p. DE-DI

- ^ Wade, W. Cecil (1898). The Symbolisms of Heraldry: Or a Treatise on the Meanings and Derivations of Armorial Bearings. London: George Redway. p. 17. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 63

- ^ Wade (1898), p. 17

- ^ Robson (1780), BAR-BAS & TRI-VER

- ^ Robson (1780), BAR-BAS & TRI-VER

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 39

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 57

- ^ Berry (1828), p. LUN-MAI

- ^ Robson (1780), pp. BAR-BAS & TRI-VER

- ^ Berry (1828), p. LUN-MAI

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), pp. 39

- ^ Berry (1828), p. FUS-FAM

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 211 & 218

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 211 & 218

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 211 & 218

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 110

- ^ Nisbet (1722), pp. 211 & 218

- ^ Berry (1828), p. ARM-ARM

- ^ Smedley, Rose & Rose (1845), p. 605

- ^ Berry (1828), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Robson (1780), pp. BAR-BAS & TRI-VER

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 39

- ^ Berry (1828), p. TRI-TRI

- ^ Edmondson (1780), p. TRI-VER

- ^ Berry (1828), p. TRI-TRI

- ^ Berry (1828), p. COU-COU

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), pp. 39

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 110

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Berry (1828), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Rothery (1915), p. 325

- ^ Berry (1828), p. CHE-CHE

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Berry (1828), p. CHE-CHE

- ^ Berry (1828), p. CHE-CHE

- ^ Clark & Wormull (1788), pp. 214

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 376

- ^ Robson (1780), p. BAR-BAS

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 40

- ^ Guillim (1638), p. 376

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 40

- ^ Berry (1810), p. 8

- ^ Kent, Samuel (1724). The grammar of heraldry: or, Gentleman's vade mecum... (Third ed.). London: John Pemberton. p. cviii. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 44

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 37

- ^ Pimbley (1908), pp. 9&10

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 164

- ^ Coats (1725), pp. 35&37

- ^ Berry (1810), p. 8

- ^ Cussans (1893), p. 77

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 37

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 126

- ^ Berry (1810), p. 34

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. BAS–BAS

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 330

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ Smedley, Rose & Rose (1845), p. 605

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. PAL–PAL

- ^ Smedley, Rose & Rose (1845), p. 601&607

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 76

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 65

- ^ Woodward (1896), p. 364

- ^ Kent (1724), p. cxx

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 65

- ^ Berry (1828), pp. PAL–PAL

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 414

- ^ du Marte, Antoine Pyron (1765). The elements of heraldry. London: J. Newbery. pp. 148–149. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Kent (1724), p. lix

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 105&375

- ^ Kent (1724), p. cliv

- ^ Clark, Hugh (1829). An Introduction to Heraldry: Containing the Origin and Use of Arms; Rules for Blazoning and Marshalling Coat Armours; the English and Scottish Regalia; a Dictionary of Heraldic Terms; Orders of Knighthood, Illustrated and Explained; Degrees of the Nobility and Gentry; Tables of Precedency, Etc., Titles and Duties of the Great Officers of State; and of the Officers of the College of Arms, Etc; and a New Chapter on Heraldry as in Conjunction with Architecture ... (11th ed.). London: Henry Washbourne. p. 46. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 280

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 150–151

- ^ Kent (1724), p. cxx

- ^ Berry (1828), p. BAR-BAR

- ^ Zieber, Eugene (1895). Heraldry in America. Philadelphia: Department of Heraldry of the Bailey, Banks & Biddle Company. p. 289. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Elvin (1889), p. 12

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 162

- ^ du Marte (1765), pp. 190

- ^ Editors (1841). The Popular Encyclopedia, Vol. III. Glasgow: Blackie and Son. p. 697. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 330

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 64

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 44

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 37

- ^ Pimbley (1908), pp. 9&10

- ^ Editors (1841), p. 697

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 64

- ^ Gough (1847), p. 44

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 244

- ^ Whitmore & Appleton (1867), p. 21

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ Clark (1829), p. 51

- ^ Kent (1724), p. cvii

- ^ Nisbet (1722), p. 40

- ^ du Marte (1765), pp. 189–190

- ^ Gough & Parker (1894), p. 37

- ^ Copinger (1910), pp. 52

- ^ Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags through the ages and across the world. New York; St. Louis; San Francisco, Auckland; Johannesburg; Kuala Lumpur; London; Montreal: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-059093-1. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ Znamierowski & Slater (2007)

- ^ Crampton, William G. (2006). Flags of the World. London: Usborne Publishing, Ltd. Retrieved 2 October 2024.