Taghlib

| Banu Taghlib | |

|---|---|

| Adnanite Arab tribe | |

| |

| Nisba | Taghlibī |

| Location | Najd, Upper Mesopotamia |

| Descended from | Taghlib ibn Wa'il |

| Parent tribe | Rabi'a |

| Branches |

|

| Religion | Miaphysite Christianity (6th–9th centuries) Islam (9th century–present) |

The Banu Taghlib (Arabic: بنو تغلب), also known as Taghlib ibn Wa'il, were an Arab tribe that originated in Jazira, however throughout history it has been argued that they were possibly Assyrian[2]. Their parent tribe was supposedly the Rabi'a, and they thus traced their descent to the Adnanites. The Taghlib were among the most powerful and cohesive nomadic tribes of the pre-Islamic era and were known for their bitter wars with their kinsmen from the Banu Bakr, as well as their struggles with the Lakhmid kings of al-Hira in Iraq (Lower Mesopotamia). The tribe embraced Miaphysite Christianity and remained largely Christian long after the advent of Islam in the mid-7th century. After early opposition to the Muslims, the Taghlib eventually secured for themselves an important place in Umayyad politics. They allied with the Umayyads and engaged in numerous battles with the rebellious Qaysi tribes during the Qays–Yaman feuding in the late 7th century.

During Abbasid rule, some individuals from the tribe embraced Islam and were given governorships in parts of the Caliphate. By the mid-9th century, much of the Taghlib converted to Islam, partly as a result of the persuasion of the Taghlibi governor of Diyar Rabi'a and founder of al-Rahba, Malik ibn Tawk. Several Taghlibi tribesmen were appointed governors of Diyar Rabi'a and Mosul by the Abbasids. In the early 10th century, a Taghlibi family, the Hamdanids, secured the governorships of these regions, and in the 930s, the Hamdanid leader Nasir al-Dawla formed an autonomous emirate out of Mosul and the Jazira. Likewise, in 945, his brother, Sayf al-Dawla, created a northern Syrian emirate based in Aleppo. The Hamdanids ruled both of these emirates until their political demise in 1002. The Taghlib as a tribe, however, had disappeared from the historical record during the early Hamdanid period.

Origins

[edit]The Banu Taghlib were originally a Bedouin (nomadic Arab) tribe that inhabited the Najd.[3] The tribe was named after its progenitor Taghlib ibn Wa'il, also known as Dithar ibn Wa'il.[4] The tribe belonged to the Rabi'a confederation and thus traced its descent to the Nizar branch of the Adnanites.[4] Their full genealogy is as follows: Taghlib/Dithār ibn Wāʾil ibn Qasit ibn Hinb ibn Afṣā ibn Duʿmī ibn Jadīla ibn Asad ibn Rabīʿa ibn Nizār ibn Maʿadd ibn Adnān.[4] Their rival and brother tribe was the Banu Bakr ibn Wa'il.[4]

Sub-groups

[edit]Information about the Taghlib's branches were in large part based on the records of the pre-Islamic Taghlibi genealogist al-Akhzar ibn Suhayma.[5] Taghlib ibn Wa'il had three sons, Ghanm, Imran and al-Aws.[6] However, in Arab genealogical literature, only the descendants of Ghanm ibn Taghlib are discussed extensively.[6] From Ghanm came the al-Araqim, which referred to the descendants of six sons of Bakr ibn Hubayb ibn Amr ibn Ghanm,[6] all of whom had eyes that resembled those of arāqim (speckled snakes; sing. al-Arqām).[7] The al-Araqim were the most important group of the Taghlib and nearly all of the genealogical history of the Taghlib centers around them.[6] The six divisions of the al-Araqim were the Jusham (the largest), Malik (second largest), Amr, Tha'laba, al-Harith and Mu'awiya.[6] Because of their size and strength, the Jusham and Malik were collectively referred to as al-Rawkān, which translated as "the two horns" or "the two numerous and strong companies".[6] The smaller Amr division of the al-Araqim was known as al-Nakhābiqa.[6]

From the Jusham division came the Zuhayr branch, from which several large sub-tribes descended, including the Attab, Utba, Itban, Awf and Ka'b lines; all of these lines were founded by the eponymous sons of Sa'd ibn Zuhayr ibn Jusham.[6] The Attab, Utba and Itban sub-tribes formed the al-Utab grouping, while the Awf and Ka'b sub-tribes formed the Banu al-Awhad.[6] Another leading Zuhayri sub-tribe was the al-Harith, whose eponymous founder was a son of Murra ibn Zuhayr.[6] The Malik division also bore numerous tribal groupings, including al-Lahazim (descendants of Awf ibn Malik), al-Abna' (descendants of Rabi'a, A'idh and Imru' al-Qays, all sons of Taym ibn Usama ibn Malik), al-Qu'ur (descendants of Malik's sons Malik and al-Harith) and Rish al-Hubara (descendants of Qu'ayn ibn Malik).[6] The Hamdanid dynasty traced its descent to the Malik division via their ancestor Adi ibn Usama ibn Malik.[8][9]

History

[edit]Pre-Islamic era

[edit]In the pre-Islamic era (pre-630s), the Taghlib were among the strongest and largest Bedouin tribes in Arabia.[6] Their high degree of tribal solidarity was reflected in the large formations they organized into during battle.[6] The tribe was involved in several major battles during this period.[5] As early as the 4th century CE, the Taghlib were within the sphere of influence of the Persian Sasanian Empire and their Arab clients, the Lakhmid kings of al-Hira.[5] It is mentioned during this time that the Sasanian king Shapur II sent Taghlibi captives to live in Darin and al-Khatt, both in the region of Bahrayn (eastern Arabia).[5]

In the late 5th century, the Taghlibi chieftain Kulaib ibn Rabiah, from the al-Harith ibn Murra line of the Zuhayr branch, was murdered by his brother-in-law, Jassas ibn Murra al-Shaybani of the Banu Bakr.[10] This precipitated a long conflict, known as the Basus War, between the Taghlib and Bakr.[5] Kulaib's brother Abu Layla al-Muhalhel assumed leadership of the Taghlib, but quit his position after the Taghlib's decisive defeat at the battle of Yawm al-Tahaluq, after which the bulk of the Taghlib fled Najd for the Lower Euphrates region.[5] There, they lived alongside the Namir ibn Qasit tribe, the Taghlib's paternal kinsmen.[5] A section of the Taghlib had already lived in the Lower Euphrates prior to the tribe's mass exodus.[5]

Concurrent with the Basus War was the rise of the Kindite Kingdom in central and northern Arabia.[5] Both the Taghlib and the Bakr became subjects of the Kingdom during the reign of al-Harith ibn Amr ibn Hujr (early 6th century).[5] After al-Harith's death (post 530), his sons Shurahbil and Salama contested the throne.[5] The Taghlib and Namir backed Salama against the Bakr who backed Shurahbil. Al-Saffah, a Taghlibi warrior from the Malik division, was commander of Salama's cavalry, while another Taghlibi, Usum ibn al-Nu'man, slew Shurahbil in battle.[5] The Basus War ended in the mid-6th century when the Taghlib and Bakr signed a peace treaty at the Dhu al-Majaz market near Mecca.[5]

The Taghlib migrated further north along the Euphrates to Upper Mesopotamia (known to the Arabs as the "Jazira") after their chieftain Amr ibn Kulthum of the Jusham division assassinated the Lakhmid king Amr ibn al-Hind in 568.[5] As late as the 8th century, Taghlibi tribesmen glorified Amr ibn Kulthum as among the most preeminent Arabs of the pre-Islamic era, and noted his poetic skills, his struggle against the kings of al-Hira and his feats in the conflict with the Bakr.[11] In 605, the Taghlib and Bakr fought on opposing sides in the Battle of Dhi Qar, with the Taghlib backing the Sasanians against the Bakr.[6]

Early Muslim period

[edit]

The Taghlib's political influence receded considerably during the advent of Islam in the mid-7th century.[6] Due to their distance from Mecca and Medina, the two cities that played the central role in Islam's development, the Taghlib were not involved in Islamic affairs in the prophet Muhammad's time.[6] During the Ridda Wars (632–633) between the Muslims and the apostate Arab tribes, the Taghlib fought alongside the latter.[6] Sections of the Taghlib, particularly the Utba line of the Zuhayr branch, fought the Muslim armies in Iraq and Upper Mesopotamia during the Islamic conquest of Persia.[6] A daughter of the Utba chieftain Rabi'a ibn Bujayr named Umm Habib was taken captive and sent to Medina, where she was purchased by Ali ibn Abi Talib; she gave birth to Ali's twins, Umar al-Kabir and Ruqayya.[6]

At some point during the Muslim conquests, the Taghlib switched allegiance to the Muslims whilst retaining their Christian faith.[6] Among the most prominent defectors was Utba ibn al-Waghl, a Kufa-based activist from the Sa'd line of the Jusham division.[6] Much of the Taghlibi troops of the Muslim army settled in Kufa.[6] During the First Muslim Civil War (656–661), members of the Taghlib fought on the side of Ali ibn Abi Talib at the Battle of the Camel (656) and the Battle of Siffin (657).[12] However, at Siffin, a significant Taghlibi force also fought alongside Mu'awiya .[12]

The fact that the Muslim state exempted the Taghlib from jizya, while retaining their Christian faith, is notable.[13] The Taghlib refused to pay the jizya like other Christian subjects and requested to pay the zakat (a tax paid by Muslims to the poor) instead.[14] The Taghlib reasoned they were Arabs and should not be treated like non-Muslims, but instead wished to be treated like Muslims.[15] Given that this tax issue had already caused some Christian Arabs to defect to the Byzantine empire, Caliph Umar conceded to their demand and instead applied on the Taghlib either the zakat or sadaqah (both taxes normally imposed on Muslims).[16] Umar's exemption was widely approved by other senior early Muslims, and later Muslim jurists opined that a Muslim ruler could waive the jizya from non-Muslims so long as the ruler collected an alternate tax that was equivalent in amount.[15] Yusuf Qaradawi argues that Muslim majority countries can apply this lesson to their non-Muslim citizens by charging non-Muslims not jizya but an equivalent tax instead (which would exempt non-Muslims from paying the zakat that is imposed on Muslims).[15]

Umayyad period

[edit]The Taghlib's shared Christian faith and proximity to the Muslims' enemy, the Byzantine Empire, was the likely reason members of the tribe were not assigned important positions in the state during the Umayyad era.[12] Nonetheless, they backed the Umayyads during the Second Muslim Civil War (680–692).[12] Initially, they nominally supported the rebellious Qaysi tribes in the Qays–Yaman conflict, an episode of the civil war.[12] However, after the Qaysi Banu Sulaym tribe encroached on their villages in the Khabur Valley and attacked the tribe with sanction from the anti-Umayyad leader Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, the Taghlib turned against the Qays.[12] The conflict with Qays likely precipitated the Taghlib's reconciliation with the Banu Bakr.[12] The Taghlibi chieftain Hammam ibn al-Mutarrif secured the peace and alliance of the two tribes by compensating the Bakr for their losses at the Battle of Dhi Qar.[12] A leader of the Taghlib, Abd Yasu', served as the Taghlib and Bakr's joint envoy to Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705).[12]

The Taghlib's champion during their conflict with the Qays was the well-known Taghlibi poet al-Akhtal, whose main poetic rival was the Qaysi Jarir, with whom he engaged in "verbal warfare" in the Umayyad court.[17] Under Abd al-Malik, al-Akhtal was the official poet of the Umayyad court and vigorously championed the Umayyads' against their opponents.[17] The Taghlibi–Qaysi conflict culminated with a decisive Taghlibi victory at Yawm al-Hashshak in the Jazira near the Tigris River, in which the Sulaymi chief Umayr ibn al-Hubab was slain; the Taghlib sent the latter's head to Abd al-Malik, who was pleased with the death of the rebel leader.[12] The last Umayyad caliph Marwan II (r. 744–750) appointed the Taghlibi tribesman and descendant of al-Saffah, Hisham ibn Amr ibn Bistam, as governor of Mosul and the Jazira.[12]

Abbasid period

[edit]The Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) reassigned Hisham ibn Amr to Sind.[12] Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785) replaced Hisham with his brother Bistam, before reassigning the latter to Adharbayjan.[12] Both Hisham and Bistam were Muslims. Another Taghlibi Muslim, Abd al-Razzaq ibn Abd al-Hamid led an Abbasid expedition against the Byzantines in the summer of 793.[12] In the early 9th century, the Adi ibn Usama line of the Malik division, known as the ʿAdī Taghlib or al-ʿAdawīyya gained political prominence in the Jazira.[12] One of their members, al-Hasan ibn Umar ibn al-Khattab was appointed governor of Mosul by Caliph al-Amin in 813.[12] Some years later, another Taghlibi linked to al-Hasan by marriage, Tawk ibn Malik of the Attab line of the Jusham division, became governor of Diyar Rabi'a under Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833).[12] Tawk's son Malik ibn Tawk served as governor of Jund Dimashq (district of Damascus) and Jund al-Urdunn (district of Jordan) under caliphs al-Wathiq (r. 842–847) and al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861). He later founded the Euphrates fortress town of al-Rahba (modern Mayadin).[18]

Hamdanid dynasty

[edit]In the 880s, a member of the Adi Taghlib, Hamdan ibn Hamdun, joined the Kharijite Rebellion against Caliph al-Mu'tadid.[19] At the time, Hamdan held a number of forts in the Jazira, including Mardin and Ardumusht, but in 895, the Abbasids captured the former and afterward, Hamdan's son Husayn surrendered Ardumusht and joined al-Mu'tadid's forces.[19] Hamdan surrendered to the Abbasids outside of Mosul and was imprisoned, but Husayn's good offices with al-Mu'tadid gained Hamdan a pardon.[19] Husayn led or participated in Abbasid expeditions against the Dulafids, the Qarmatians and Tulunids during the reign of Caliph al-Muktafi (r. 902–908), but fell from grace for taking part in the plot to install Abdallah ibn al-Mu'tazz as caliph in 908.[19] Husayn's brothers Abu'l Hayja Abdallah (governor of Mosul in 905–913 and 914–916), Ibrahim (governor of Diyar Rabi'a in 919), Dawud (governor of Diyar Rabi'a in 920) and Sa'id remained loyal to the Abbasids and Husayn eventually gained a pardon and was appointed governor of Diyar Rabi'a in 910.[19] He later revolted, was captured and executed in 916.[19] Abu al-Hayja', meanwhile, was again made governor of Mosul in 920, serving until his death in 929.[19]

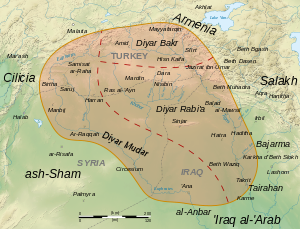

Upon Abu al-Hayja's death, his son Nasir al-Dawla, who ruled as his father's deputy ruler in Mosul, struggled to secure the governorship of that city.[20] His rule was opposed by his uncles Sa'id and Nasr, the Banu Habib (a rival Taghlibi clan) and Caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908–929).[20] By 935, Nasir al-Dawla had prevailed against them and was appointed by Caliph al-Radi (r. 934–940) as governor of Mosul and all three provinces of the Jazira, i.e. Diyar Rabi'a, Diyar Mudar and Diyar Bakr.[20] That year the Banu Habib, numbering 12,000 horsemen and their families, left Hamdanid-ruled Nisibin and defected to Byzantium. They were apportioned lands along the frontier and given animals and other gifts by the Byzantines, who were seeking to buttress their manpower along with frontier. Afterward, the Habib raided the Islamic side of the frontier, mainly Diyar Mudar, annually during harvest time and captured the forts of Hisn Ziyad and Hisn Mansur.[21]

In 942, Nasir al-Dawla became the effective ruler of the Abbasid Caliphate until being outmaneuvered by his rebellious Turkish officer, Tuzun, the following year.[20] Nasir al-Dawla was deposed as governor of Mosul and the Jazira by his sons in 967.[20] The province remained in Hamdanid hands until 1002.[20] Meanwhile, Nasir al-Dawla's brother, Sayf al-Dawla founded the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo and northern Syria in 945.[22] His descendants would continue to rule the emirate until being deposed by the ghulam (slave soldier), Lu'lu' al-Kabir in 1002.[23] The Hamdanids did not depend on their Taghlibi tribesmen for matters of the state, relying instead on non-Arab ghilman and bureaucrats for military and fiscal affairs. After the early years of the Hamdanid dynasty, the Taghlib, like many Arab tribes established in the region before and after the 7th-century Muslim conquests, "disappeared into obscurity".[24]

Religion

[edit]Small numbers of Taghlibi tribesmen converted to Islam during the Umayyad era (661–750) and early Abbasid era (8th century), including the small Taghlibi community of Kufa, some tribesmen in Qinnasrin and noted individuals, such as the Umayyad court poets Ka'b ibn Ju'ayl and 'Umayr ibn Shiyaym.[12] The vast majority remained Christian during this period.[12] Later in the Abbasid era, in the 9th century, significant numbers of Taghlibi tribesmen embraced Islam and attained higher office in the state.[12] Apparently, the mass conversion of the Taghlib to Islam occurred in the second half of the 9th century during the reign of al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842).[9] At around the same time, Malik ibn Tawk persuaded Sahl ibn Bishr, a great-grandson of al-Akhtal, to convert to Islam along with all of al-Akhtal's descendants.[9] The Banu Habib converted to Christianity in 935 when they defected to Byzantium. The historian Asa Eger comments, "The idea that they [the Banu Habib] converted to Christianity may only partially be true, as many may still [have] retained their Christian past identities."[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor, ed. (1987). "E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936". E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume III: E–I'timād al-Dawla. Leiden: BRILL. p. 38. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- ^ 2009, p. 53

- ^ Lecker 2000, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b c d Lecker 2000, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lecker 2000, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Lecker 2000, p. 91

- ^ Ibn Abd Rabbih (2011). Boullata, Issa J. (ed.). The Unique Necklace, Volume 3. Garnet Publishing. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-85964-239-9.

- ^ Ibn Khallikan (1842). De Slane, Mac Guckin (ed.). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Volume 1. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. p. 404.

- ^ a b c Lecker 2000, p. 93.

- ^ Levi Della Vida, p. 362.

- ^ Blachère, R. (1960). "'Amr ibn Kulthum". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. I: A–B (new ed.). Leiden and New York: Brill. p. 452. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Lecker 2000, p. 92.

- ^ Lecker 2000, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Asma Afsaruddin. Contemporary Issues in Islam. Edinburgh University Press. p. 188.

- ^ a b c Yusuf Qaradawi (2011). Fiqh Al-Zakāh: A Comprehensive Study of Zakah Regulations and Philosophy in the Light of the Qur'an and Sunnah. p. 53-54.

- ^ Idris El Hareir, Ravane Mbay. The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. p. 201.

- ^ a b Blachère, R. (1960). "Al-Akhtal". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. I: A–B (new ed.). Leiden and New York: Brill. p. 331. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- ^ Lecker 2000, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d e f g Canard 1971, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f Canard 1971, p. 127.

- ^ Eger 2014, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Canard 1971, p. 129.

- ^ Canard 1971, p. 130.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 283.

- ^ Eger 2014, p. 292.

Bibliography

[edit]- Canard, M. (1971). "Hamdanids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469525.

- Eger, A. Asa (2014). The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780857726858.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Lecker, M. (2000). "Taghlib b. Wāʾil". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 89–93. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Levi Della Vida, G. (1986). "Kulayb b. Rabīʿa". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 362. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Nicholson, Reynold A. (1907). A Literary History of the Arabs. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 58. ISBN 9780521095723.