Bans on communist symbols

Communist symbols have been banned, in part or in whole, by a number of the world's countries.[1] As part of a broader process of decommunization, these bans have mostly been proposed or implemented in countries that belonged to the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, including some post-Soviet states. In some countries, the bans also extend to prohibit the propagation of communism in any form, with varying punishments applied to violators. Though the bans imposed by these countries nominally target the communist ideology, they may be accompanied by popular anti-leftist sentiment and therefore a de facto ban on all leftist philosophies, such as socialism, while not explicitly passing legislation to ban them.

Summary table

[edit]| Country | Legality of communist symbols | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Illegal | Educational purposes; communist symbols that are not Soviet-related | |

| Illegal | Educational purposes; communist symbols that are not related to the Communist Party of Germany | |

| Legal | — | |

| Illegal | — | |

| Illegal | Communist symbols that are not Soviet-related | |

| Illegal | Communist symbols that are not Soviet-related | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Legal | — | |

| Illegal | Educational purposes; communist symbols that are not related to North Korea | |

| Legal | — | |

| Illegal | Educational purposes | |

| Legal | — |

General bans

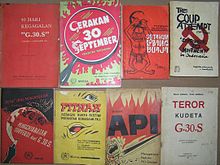

[edit]Indonesia

[edit]

"Communism / Marxism–Leninism" (official terminology) was banned in Indonesia following the aftermath of the 30 September coup attempt and the subsequent anti-communist killings, by the adoption of TAP MPRS no. 25/1966 in the 1966 MPRS General Session[2] and Undang Undang no. 27/1999 in 1999 (the corresponding explanatory memorandums of whom explain that "[Communism / Marxism-Leninism includes] the struggle fundaments and tactics taught by ... Stalin, Mao Tse Tung et cetera ..."), which are still in force. The law does not explicitly declare a ban on symbols of communism, but Indonesian police frequently use the law to arrest people displaying them.[3] Some of its violators were people with no knowledge of symbols of communism, in which cases the authorities frequently freed them with only minor punishment or small fine applied.[4] The display of such symbols in an attempt to propagate "Communist / Marxist-Leninist" ideals are considered a high treason, and could be punished by up to 20 years imprisonment.[5]

Other socialist and left-wing symbols, while not officially prohibited by law (as democratic socialism itself remains acceptable in the country) are still widely condemned by the Indonesian government and considered as being closely related to communism. Such symbols include the red star, the red flag, socialist heraldry, and anthems or slogans such as The Internationale and "Workers of the world, unite!". Despite this, The Internationale was still used during International Labour Day. It's not known whether the symbols of ruling Communist parties in other ASEAN countries such as Vietnam and Laos are also outlawed in Indonesia as well.[citation needed]

In addition, since the New Order regime took power in 1967, the hammer and sickle has been highly stigmatized in the country, similar to the stigma surrounding Nazi symbolism in the Western world and the Imperial Japanese flag in South Korea. As such, displaying the symbol in public, even without any political intentions, is still regarded as highly offensive, especially among Muslims and political Islamists.[citation needed]

In April 2017, Indonesian police detained a Malaysian tourist at a hotel in Mataram for wearing a T-shirt with an image of the hammer and sickle symbol. The tourist was not aware that communist symbols were banned in Indonesia. The police seized the T-shirt and released the tourist after giving him a warning.[6] In May 2018, a Russian tourist was also detained by police in Bali for displaying a Soviet victory banner, which also contains the symbol.

Ukraine

[edit]In April 2015, the Verkhovna Rada passed a law banning communist and Nazi symbols, following the Revolution of Dignity and start of the war with Russia in 2014.[7] Earlier, in 2012, the city of Lviv in Western Ukraine banned the public display of all communist symbols, including ones not related to Soviet communism.[1] On 17 December 2015, all communist parties were officially banned in Ukraine.[8] Singing or playing the former anthem of the Soviet Union, any other former anthems of the Soviet republics, or The Internationale is punishable with a sentence of up to five years in prison.[9] In July 2019, the Constitutional Court upheld the law, equating communism to Nazism.[10][11]

Bans on certain symbols

[edit]Georgia

[edit]In Georgia the use of Soviet-era symbols on government buildings is prohibited, as is their display in public spaces, although this law is rarely enforced by authorities.[12] A ban on communist symbols was first proposed in 2010,[13] but it failed to define the applicable sanctions.[14] In 2014, there was a proposal to amend the ban to introduce clearer parameters.[15]

Germany

[edit]The flag of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) was outlawed as an unconstitutional and criminal symbol in West Germany and West Berlin, where it was referred to as the Spalterflagge (secessionist flag) until the late 1960s, when the ban was lifted. The flag and emblem of the now defunct Communist Party of Germany (KPD) is still banned in the country under section 86a of the German criminal code, while the hammer and sickle symbol itself is considered a universal symbol and is legally used by the contemporary German Communist Party (DKP) and various other organisations and media.[citation needed]

Latvia

[edit]In Latvia, the perception of the USSR is highly negative due to the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. In June 2013, the Latvian parliament approved a ban on the display of Soviet and Nazi symbols at all public events. The ban involves flags, anthems, uniforms, and the Soviet hammer and sickle.[16][17]

Lithuania

[edit]Lithuania, similarly to Latvia, banned Soviet and Nazi symbols in 2008 (Article 18818 of the Code of Administrative Offences) under the threat of a fine.[18] Collection, antiquarian trade and educational activities are exempt from the ban.[19] Article 5 of the Law on Meetings prohibits meetings involving Nazi and Soviet imagery.[20]

South Korea

[edit]It is illegal to display the flag of North Korea or the flag of the Workers' Party of Korea in South Korea. They are deemed unconstitutional symbols, although some exceptions exist, particularly during international sport events.[21][22]

Former bans

[edit]Hungary

[edit]Hungary had a law (Article 269/B of the Criminal Code (2000)) that banned the use of symbols of fascist and communist dictatorships.[23][24] The same year the Constitutional Court upheld the law when it was challenged, claiming that the involved restriction of the freedom of expression was justified.[25] In July 2008 the European Court of Human Rights considered the challenge of Attila Vajnai who was charged with a misdemeanor for use of the red star and declared the Hungarian law to be in violation of the freedom of expression. The Court recognised the gross violations by the Nazi and communist regimes; however, it noted that modern Hungary is a stable democracy with negligible chance of dictatorship, therefore restrictions on the freedom of expression have no justification in the country in the form of a "clear, pressing and specific social need".[26] Eventually the law was annulled in 2013 by the Constitutional Court, citing the lack of precise definition and the European Court of Human Rights.[27] In March 2017, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán introduced a draft law that outlaws merchandise featuring "totalitarian symbols", which includes symbols like the Nazi swastika or the communist five-pointed red star.[28] This included the red star on the logo of the Dutch brewing company Heineken, which the company claimed has no communist origins or political connotations, and which the company will defend like all other trademarks.[29]

Moldova

[edit]In 2009, such a ban was proposed in Moldova by parliamentarian Oleg Serebryan,[citation needed] and the law came into effect in 2012.[30] The Constitutional Court of Moldova found the law unconstitutional and overturned it in 2013.[23]

Poland

[edit]In 2009, Poland amended Article 256 of its penal code, banning the display of "fascist, communist [and] other totalitarian symbols" unless they were being used "as part of artistic, educational, collecting or academic activity." On 19 July 2011, the Constitutional Tribunal of Poland found the amendment to be partially unconstitutional as it limited freedom of expression.[31] In June 2017, Poland updated its "decommunization" legislation to include Soviet propaganda monuments, prompting negative reactions from the Russian government.[32] While the "promotion of communist ideas" remains illegal in Poland, the display of communist symbols is no longer explicitly prohibited.[33][34]

Taiwan (Republic of China)

[edit]The Kuomintang government in Taiwan outlawed the flag of the People's Republic of China in 1952, pursuant to the Temporary Provisions against the Communist Rebellion in the country's constitution. The temporary provisions were repealed in 1991, but a general ban on communist ideology and symbolism in the National Security Law of the Republic of China, promulgated in 1976, was not annulled until 2011.[35]

In late 2020, a legislator from the Democratic Progressive Party proposed an amendment to the National Security Law which would ban the public display of the flag of the People's Republic of China.[36] However, as of 2022[update], no such legislation has been passed.

United States

[edit]During the Red Scare of 1919–20 in the United States, many states passed laws forbidding the display of red flags, including Minnesota, South Dakota, Oklahoma,[37] and California. In Stromberg v. California, the United States Supreme Court held that such laws were unconstitutional.[38]

Proposed anti-communist legislation

[edit]Albania

[edit]Albania's Institute for Communist Crimes (ICC) proposed a ban on communist-era films, sparking hostile reactions from the public.[39]

Brazil

[edit]In 2016, Eduardo Bolsonaro, a federal deputy for São Paulo and the son of then-deputy and future president Jair Bolsonaro, proposed a bill to criminalize the promotion of communism. The draft proposed that offenders be given two to five years in prison and a fine if they manufacture, commercialize, distribute or convey symbols or propaganda that use the hammer or sickle or any other means of dissemination favourable to communism.[40] As of December 2022[update], the bill is in the Constitution and Justice Commission of the Chamber of Deputies of Brazil.[41]

Bulgaria

[edit]In Bulgaria, lawmakers voted on first reading of a proposed law on 24 November 2016 to make the public display of communist symbols illegal. The law, known as the "Criminal Nature of the Communist Regime", requires that signs and items created during the communist regime glorifying the former communist party and its leaders be removed from public places.[42][43][44] The proposal, however, was never put to a second reading, never signed by the President of Bulgaria nor published in Bulgaria's State Gazette and hence never became law. Both the parliamentary session and convocation in which the law was proposed later ended, thus rendering the proposal dead.[45]

Czech Republic

[edit]In 1991, in Czechoslovakia the criminal code was amended with w § 260 which banned propaganda of movements which restricted human rights and freedoms, citing Nazism and communism. Later the specific mentions of these were removed citing their lack of clear legal definition. Nevertheless, the law itself was recognised as constitutional.[23][46] However, in 2005, there was a petition in the Czech Republic to ban the promotion of communism and in 2007, there was a proposed amendment to the law to ban communist symbols. Both attempts failed.[47][48]

Estonia

[edit]In early 2007 the Riigikogu was proceeding a draft bill amending the Penal Code to make the public use of Soviet and Nazi symbols punishable if used in a manner disturbing the public peace or inciting hatred.[49] The bill did not come into effect as it passed only the first reading in the Riigikogu.[50]

European Union

[edit]In January 2005, Vytautas Landsbergis, backed by other Members of the European Parliament, such as József Szájer from Hungary, urged a ban on the communist symbols in the European Union, in addition to Nazi symbols.[51][52]

In February 2005, the European Commission rejected calls for a proposed Europe-wide ban on Nazi symbols to be extended to cover communist symbols as well on the basis that it was not appropriate to deal with this issue in rules aimed at combatting racism. However, this rejection did not rule out the individual member states having their own laws in this respect.[53][54]

In December 2010, the European Commission published a report titled "The memory of the crimes committed by totalitarian regimes in Europe" addressed to the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, in which it mentions the banning of communist symbols by some Member states (Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and Lithuania) and concludes that "the European Union has a role to play, within the scope of its powers in this area, to contribute to the processes engaged in the Member States to face up to the legacy of totalitarian crimes".[55]

In September 2019, the European Parliament approved a joint motion for a "Resolution on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe" with 535 votes in favour, 66 against and 52 abstentions.[56] Specifically, in points 17 and 18 of the resolution "expresses concern about the continued use of symbols belonging to totalitarian systems in the public sphere and for commercial purposes", as well as noting "the continued existence in public spaces in some Member States of monuments and memorials (parks, squares, streets etc.) glorifying totalitarian regimes, which paves the way for the distortion of historical facts about the consequences of the Second World War and for the propagation of the totalitarian political system".[57]

Romania

[edit]Law 51/1991, (article 3. h) on the National Security of Romania considers the following as threats to national security: "the initiation, organisation, perpetration, or the supporting in any way of the totalitarian or extremist actions of a communist, fascist, iron guardist, or of any other origin, of the racial, anti-Semitic, revisionist, separatist actions that can endanger in any way the unity and territorial integrity of Romania, as well as the instigation to deeds that can put in, danger the order of the state governed by the rule of law".[58] However, symbols are not specifically mentioned in the law.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Brooke, James. "Communist Symbol Ban Spreads in Europe". Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Explanations on banning communism and Marxism-Leninism in Indonesia Archived 17 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

- ^ Police chief explanation on banned hammer and sickle symbol in Indonesia Archived 16 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

- ^ Farmer arrested after wearing shirt with hammer and sickle Archived 11 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

- ^ Undang Undang no.27/1999, laws on Communism and Marxism-Leninism Archived 30 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Indonesian)

- ^ Malaysian detained in Indonesia for wearing T-shirt with communist symbol, The Straits Times, 14 April 2017, archived from the original on 29 July 2017, retrieved 17 May 2017

- ^ Shevchenko, Vitaly (14 April 2015). "Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine bans Communist party for 'promoting separatism'". The Guardian. 17 December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Luhn, Alec (21 May 2015). "Ukraine bans Soviet symbols and criminalises sympathy for communism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ "RFE/RL: Ukraine's Constitutional Court upholds law equating communism to Nazism". Kyiv Post. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Time, Current (17 July 2019). "Ukraine's Constitutional Court Upholds Law Equating Communism To Nazism". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Morrison, Thea (10 May 2018). "The Banning of Soviet Symbols in Georgia". Georgia Today. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Georgia: Ban on Soviet Symbols Proposed - Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov. 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Georgia to enforce ban on communist symbols". 31 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Communist symbols to be banned in Georgia". BBC News. 4 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Latvia bans the use of USSR symbols during public events". Baltic News Network. 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Latvia Bans Soviet Symbols". The Moscow Times. 23 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Lithuanian ban on Soviet symbols". BBC News. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Lithuanian penal code". 5 November 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021.

- ^ Joint amicus curiae brief, p. 11

- ^ Rutherford, Peter (12 September 2014). "Seoul reminds citizens of North Korea flag ban". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "South Korea Makes Olympic Exception for North Korean Flag". aroundtherings.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Analysis of the Law on Prohibiting Communist Symbols - Human Rights in Ukraine". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Hungarian Criminal Code 269 / B. § 1993

- ^ Joint amicus curiae brief, p. 9

- ^ "European court overturns Hungarian prohibition on "communist" star". Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Gulyas, Veronika (20 February 2013). "Hungary Court Annuls Ban on Fascist, Communist Symbols". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Hungary threatens to ban Heineken's red star as 'communist'", The Guardian, 24 March 2017, archived from the original on 28 March 2017, retrieved 29 March 2017

- ^ "Heineken will never remove its iconic red star: 'defending it to its core'". BeverageDaily. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "Moldova: Ban on Use of Communist Symbols - Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Joint amicus curiae brief, p. 12

- ^ "Russia warns Poland not to touch Soviet WW2 memorials", BBC News, 31 July 2017, archived from the original on 1 August 2017, retrieved 2 August 2017

- ^ "Koszulki z sierpem i młotem nie są zakazane". wyborcza.pl. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Brudziński chce ścigać za sierp i młot, ale symbole komunistyczne są legalne. W przeciwieństwie do faszystowskich". oko.press. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "國家安全法刪除第二條及第三條條文;並修正第六條條文" (PDF) (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Office of the President. 23 November 2011.

- ^ Chen, Yun; Xie, Dennis (3 October 2020). "DPP bill to ban promoting China or flying its flag". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Zechariah Chafee, Jr., Freedom of Speech (NY: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 180ff., Appendix V

- ^ "Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931)". 1931.

- ^ Fatjona Mejdini (16 March 2017), Proposed Ban on Albanian Communist Films Sparks Backlash, Balkan Insight, retrieved 1 April 2017

- ^ Nobre, Noéli (24 July 2017). "Projeto criminaliza apologia ao comunismo" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Chamber of Deputies of Brazil. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "PL 5358/2016". Chamber of Deputies of Brazil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Parliament Passes Amendments to Act Declaring the Criminal Nature of the Communist Regime in Bulgaria". Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ "New protests for the removal of the statue of the Soviet Army in Sofia". Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ "Bulgaria bans public display of communist symbols". Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ "Народно събрание на Република България - Законопроекти". parliament.bg. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Joint amicus curiae brief for the Constitutional Court of Moldova on the compatibility with European standards" (PDF). p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "Communists in Czech Politics". Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Joint amicus curiae brief, p. 13

- ^ "Sitting reviews". Riigikogu. 24 January 2007. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Ants Erm: Erinevalt venelaste ajaloost on Venemaa ajalugu Eestis vaid vägivald, küüditamine ja kommunistlik diktatuur" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. 28 November 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Estonian MEP supports ban of communist symbols". The Baltic Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "EU ban urged on communist symbols". BBC News. 3 February 2005. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ JOINT AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF, p. 24

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Europe - EU rejects Communist symbol ban". news.bbc.co.uk. 8 February 2005. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "/* COM/2010/0783 final */ REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND TO THE COUNCIL The memory of the crimes committed by totalitarian regimes in Europe". European Commission. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Results of vote in Parliament". European Parliament. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "LAW on the National Security of Romania" (PDF). Part I, No. 163. "Monitorul Oficial"(Official Gazette of Romania). 7 August 1991. p. 2. Retrieved 11 April 2020.