Old City (Baku)

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Azerbaijani. (March 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower |

| Location | Baku, Absheron Peninsula, Azerbaijan |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Inscription | 2000 (24th Session) |

| Endangered | 2003–2009[1] |

| Area | 21.5 ha (53 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 12 ha (30 acres) |

| Website | www |

| Coordinates | 40°22′N 49°50′E / 40.367°N 49.833°E |

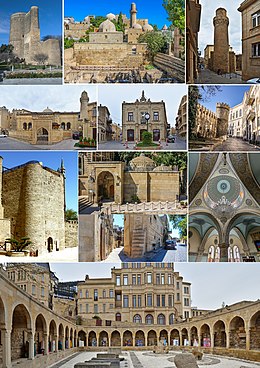

Old City or Inner City (Azerbaijani: İçərişəhər)[2] is the historical core of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The Old City is the most ancient part of Baku,[3] which is surrounded by walls. In 2007, the Old City had a population of about 3,000 people.[4] In December 2000, the Old City of Baku, including the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and Maiden Tower, became the first location in Azerbaijan to be classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

History

[edit]

The Old City, including its Maiden Tower, is widely accepted to date at least to the 12th century, with some researchers contending that construction dates as far back as the 7th century. The question has not been completely settled.[5]

During this medieval period of Baku, such monuments as the Synyg Gala Minaret (11th century), the fortress walls and towers (11th–12th centuries), the Maiden Tower, the Multani Caravanserai and Hajji Gayyib bathhouse (15th century), the Palace of the Shirvanshahs (15th–16th centuries), the Bukhara Caravanserai and Gasimbey bathhouse (16th century) were built.

In 1806, when Baku was occupied by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Persian War (1804–13),[6] there were 500 households and 707 shops, and a population of 7,000 in the Old City (then the only neighbourhood of Baku) who were almost all ethnic Tats.[7] Between 1807 and 1811, the city walls were repaired and the fortifications extended. The city had two gates: the Salyan Gates and the Shemakha Gates. The city was protected by dozens of cannons set on the walls. The port was re-opened for trade, and in 1809 a customs office was established.[8]

It was during this period that Baku started to extend beyond the city walls, and new neighbourhoods emerged. Thus the terms Inner City (Azerbaijani: İçəri Şəhər) and Outer City (Azerbaijani: Bayır Şəhər) came into use. Referring to the early Russian rule, Bakuvian actor Huseyngulu Sarabski wrote in his memoirs:[9]

Baku was divided into two sections: Ichari Shahar and Bayir Shahar. Inner City was the main part. Those who lived in the Inner City were considered natives of Baku. They were in close proximity to everything: the bazaar, craftsmen's workshops and mosques. There was even a church there, as well as a military barracks built during the Russian occupation. Residents who lived inside the walls considered themselves to be superior to those outside and often referred to them as the "barefooted people of the Outer City".

With the arrival of Russians, the traditional architectural look of the Old City changed. Many European buildings were constructed during the 19th century and early 20th century, using styles such as Baroque and Gothic.

In 1865, a part of the city walls overlooking the sea was demolished, and the stones were sold and used in the building of the Outer city. The money obtained from this sale (44,000 rubles) went into the construction of the Baku Boulevard. In 1867, the first fountains of Baku appeared in the Boulevard.

In this period, two more gates were opened, one of them being famous Taghiyev Gate (1877). The opening of new gates and passes continued well into the Soviet period.

The church mentioned by Huseyngulu Sarabski was the Armenian Church of the Holy Virgin, built under Persian rule between 1797 and 1799 in the shadow of the Maiden Tower, defunct since 1984 and demolished in 1992.[10]

Neighbourhoods

[edit]

The Old City was divided into several quarters, which also served as social divisions. Sometimes, the divisions of the Old City were named after their mosque: for example, Juma Mosque quarter, Shal Mosque quarter, Mahammadyar Mosque quarter, etc.[11]

List of main neighborhoods

[edit]- Seyyids, a quarter of clergymen

- Aghshalvarlilar, a quarter of city nobles, literally "those with white pants"

- Bozbashyemeyenler, a quarter of "those who do not eat meat"

- Gemichiler, a quarter of shipbuilders and sailors

- Hamamchilar, a quarter of public bath workers

- Arabachilar, a quarter of wagoners and cart-drivers

- Noyutchuler, a quarter of oil workers

- Juhud Zeynallilar, a Jewish quarter

- Lezgiler, a quarter of Dagestani armourers and blacksmiths

- Gilaklar, a quarter of merchants from Gilan

Underground infrastructure

[edit]In 2008, an ancient underpass, dated back to the 19th century, was discovered while holding reconstruction at Vahid park. The workers marched about 200 metres (660 ft) along the tunnel, but then stopped, having met with water and silt masses. Judging by the photographs taken in the cave, the tunnel is built very thoroughly, the walls, ceiling and floor of the tunnel are paved with white sawn stone. The workers also found a handful of coins of the Soviet period, suggesting that there was somebody in the tunnel before them, but the unknown went down at least 20 years ago.[12]

According to scholar Vitaly Antonov, in the late 18th century Baku was the Caucasian center of the revolutionary movement, and the found underpass was dug to save the governor in case of mass riots in the city. Another version is that this passage is one of the several, leading to the ancient Sabayil Castle, flooded by the Caspian Sea. There are several tunnels leading from the Palace of Shirvanshahs and Synykh Gala, situated in Icheri Shekher, to the sea. Synykh Gala was the mosque in the 15th century, in the times of the Shah Ismail Khatai, and was destroyed by the troops of Peter I. That is, the discovered passage is part of the underground network connecting the city of Sabayil to the land.[13]

Education

[edit]The first known madrasa in the Old City was opened in the 12th century, and amongst its popular lectors was Baba Kuhi Bakuvi. Four hundred years later, another distinguished scholar named Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (born in 1403) founded a Darulfunun (the House of Arts and Sciences, a prototype of a modern university) at the Palace of the Shirvanshahs. But with the fall of the Shirvanshahs' state, the education in Baku gradually diminished. By 1806 there remained only twelve mollakhanas (primary and secondary schools, kept by mosques) in the Old City, and only three of them survived into the 20th century. Later, all such schools were closed and replaced with modern kindergartens and state secular schools.

World Heritage Site

[edit]In December 2000, the Old City of Baku with the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and Maiden Tower became the first location in Azerbaijan classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Three years later, in 2003, UNESCO placed the Old City on the List of World Heritage in Danger, citing damage from a November 2000 earthquake, poor conservation, and "dubious" restoration efforts.[14]

In 2009, the World Heritage Committee praised Azerbaijan for its efforts to preserve the walled city of Baku and removed it from the endangered list.[15][16] (See List of World Heritage Sites in Azerbaijan)

Old City in films

[edit]

Some scenes of famous Azerbaijani and USSR movies such as "Diamond hand", "Amphibian man", "Aybolit-66", "Teheran-43", "Don not be afraid, I'm with you" which are famous around the world were shot in Old City.[citation needed]

The well-known scene of "In foreign country – Istanbul" of "Brilliant hand" was shot in Old City through the decision of Leonid Gayday. The old streets of Old City, Shirvanshahs' Palace, minarets of mosques and fortress walls appear in the movie. A monument of Yuri Nikulin was erected in Icherisheher, where the movie was shooting.[citation needed]

Other film scenes that were shot in the Old City include:[citation needed]

- "Arshin Mal Alan" (1945), film directors: R.Tahmasib and N.Leshenko

- "If Not That One, Then This One" (1956), film director: Huseyn Seyidzadeh

- "A Telephone Girl" (1962), film director: Hasan Seyidbeyli

- "Where is Ahmad" (1963), film director: Adil Isgenderov

- "Arshin Mal Alan" (1965), film director: Tofig Taghizadeh

- "The last night of Childhood" (1968), film director: Arif Babayev

- "In a southern city" (1969), film director: Eldar Guliyev

- "Shared bread" (1969), film director: Shamil Mahmudbeyov

- "The Day Passed" (1971), film director: Arif Babayev

- "The most important interview" (1971), film director: Eldar Guliyev

- "Amphibian Man" (1961), film director: V.Chebotaryov and G.Kazanski (Mosfilm)

- "Aybolit-66" (1961), film director: R.Bikov (Mosfilm)

- "The Diamond Arm" (1968), film director: L.Gayday (Mosfilm)

- "Teheran-43" (1981), film director: A.Alov və V.Kaumov (Mosfilm)

Documentary

[edit]- Old city (film, 1964), film director: Alibala Alakberov

- Old city (film, 1978), film director: Nijat Bakirzadeh

- A walk in the Old City (2003), film director: Javid Imamverdiyev

Character and legacy

[edit]

For a long period of time, an explicit symbol of the Old City was a mulberry tree located behind the Djuma Mosque.[citation needed] It was believed that the tree was several hundred years old. The tree made its way into many sayings and songs popular in the Old City and became a local landmark. The place where that tree was located was referred to as Mulberry Tree Square. However, in the 1970s, the mulberry tree was cut down, because of the nearby construction works.

Another popular landmark of the Old City is the local bookstore that sells mostly second-hand, but also new books. Situated amongst the Bukhara and the Multani Caravanserais, the Maiden Tower, and Hajinski's Palace (otherwise known as Charles de Gaulle House because he stayed there during World War II), it is a popular destination of Bakuvian students and bibliophiles, mostly because of its low prices.

The Old City of Baku is depicted on the obverse of the Azerbaijani 10 manat banknote issued since 2006.[17]

Gallery

[edit]-

Azerbaijani Carpets

References

[edit]- ^ "World Heritage Committee removes Baku from Danger List welcoming improvements in the ancient city's preservation]". UNESCO.

- ^ "İçəri Şəhərə xoş gəlmişsiniz!".

- ^ Akhundov, Fuad. "6.2 Walking Tour: Baku's Old City". Azerbaijan International. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Vəfalı, Təbriz (8 September 2007). "İçərişəhərin əhalisi azalıb" (in Azerbaijani). Həftə İçi. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Teymur, Mir (Summer 2000). "Ichari Shahar – The Heart of Baku: A Living Monument from the Middle Ages". Azerbaijan International.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Minahan, James B. (2014-02-10). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 9781610690188. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Фатуллаев, Шамиль. Градостроительство Баку XIX – Начала XX Веков. Баку, Институт архитектуры и искусства Академии наук АзССР, 1978

- ^ Sarabski, Hüseynqulu. Köhnə Bakı. Bakı, 1958

- ^ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden – Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9, p. 103.

- ^ Alakbarov, Farid. Baku's Old City: Memories of How It Used to Be. Azerbaijan International, Autumn 2002.

- ^ Ancient underpass discovered near Icheri Sheher – PHOTO

- ^ "The discovered in Baku underpass may become a clue to the new mysteries of the Azerbaijani history". Archived from the original on 2011-08-15.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage site: the Walled City of Baku with the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and the Maiden Tower

- ^ World Heritage Committee hails Azerbaijan for preservation of Baku Archived 2009-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hürriyet UNESCO adds more sites to its world heritage list

- ^ "National currency: 10 manat". www.cbar.az. Central Bank of Azerbaijan. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- UNESCO World Heritage site: Walled City of Baku with the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and the Maiden Tower

- Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower UNESCO collection on Google Arts and Culture