Grand Duchy of Baden

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2020) |

Grand Duchy of Baden Großherzogtum Baden | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1918 | |||||||||

Flag

(1891–1918) | |||||||||

| Anthem: Badnerlied | |||||||||

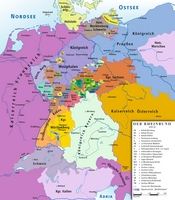

The Grand Duchy of Baden within the German Empire | |||||||||

Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden (orange) | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | Karlsruhe | ||||||||

| Official language | German | ||||||||

Common languages | Alemannic, South Franconian, Palatinate | ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Grand Duke | |||||||||

• 1806–1811 | Charles Frederick (first) | ||||||||

• 1907–1918 | Friedrich II (last) | ||||||||

| Minister-President | |||||||||

• 1809–1810 | Sigismund Reitzenstein (first) | ||||||||

• 1917–1918 | Heinrich Bodman (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Landtag | ||||||||

| Erste Kammer | |||||||||

| Zweite Kammer | |||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 27 April 1803 | |||||||||

• Grand Duchy | 24 October 1806 | ||||||||

| 18 January 1871 | |||||||||

| 14 November 1918 | |||||||||

• Established | 1806 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1918 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 15,082 km2 (5,823 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1803 | 210,000 | ||||||||

• 1905 | 2,009,320 | ||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Grand Duchy of Baden (German: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in south-west Germany on the east bank of the Rhine. It originally existed as a sovereign state from 1806 to 1871 and later as part of the German Empire until 1918.[1][2]

The duchy's 12th-century origins were as a margraviate that eventually split into two, Baden-Durlach and Baden-Baden, before being reunified in 1771. The territory grew and assumed its ducal status after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire but suffered a revolution in 1848, whose demands had been formulated in Offenburg the previous year at a meeting now considered the first-ever democratic program in Germany.[3] With the collapse of the German Empire it became part of the Weimar Republic under the name Republic of Baden.

The Grand Duchy of Baden was bordered to the north by the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Grand Duchy of Hesse, to the west by the Rhine, to the south by Switzerland, and to the east mainly by the Kingdom of Württemberg. Its unofficial anthem has been the Badnerlied, or Song of the People of Baden, which has four or five traditional verses and many more added: there are collections with up to 591 verses.

Creation

[edit]Baden came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subsequently split into various smaller territories that were unified in 1771. In 1803 Baden was raised to Electoral dignity within the Holy Roman Empire, with ecclesiastical and secular territories added to it during the German mediatisation. Upon the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Baden became the much-enlarged Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1815 it joined the German Confederation.

French Revolution and Napoleon

[edit]The outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1792 saw Baden joining the First Coalition against France. The conflict devastated the margraviate's countryside. Baden was defeated in 1796 with Margrave Charles Frederick being compelled to pay an indemnity and cede his territories on the left bank of the Rhine to France. In 1803, largely owing to the good offices of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, Charles Frederick received the Prince-Bishopric of Constance, part of the Rhenish Palatinate, and other smaller districts, together with the dignity of a prince-elector. Baden then changed sides in 1805 to join France under Napoleon in the War of the Third Coalition. France and its allies won the war, and in the Peace of Pressburg the same year, Baden obtained the Breisgau and other territories in Further Austria at the expense of the Austrian Empire. In 1806, Charles Frederick joined the Confederation of the Rhine, declared himself a sovereign prince and grand duke, and received additional territory.[4]

Baden continued to assist France militarily, and by the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1809, it was rewarded with accessions of territory at the expense of the Kingdom of Württemberg. Having quadrupled the area of Baden, Charles Frederick died in June 1811, and was succeeded by his grandson Charles, who was married to Stéphanie de Beauharnais (1789–1860) a cousin of French empress Josephine's first husband and adopted daughter of Napoleon.[4]

The Napoleonic Code was adopted in 1810, and remained in force until the adoption of the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch in 1900.[5]

Charles fought for his father-in-law until after the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, when he joined the Sixth Coalition.[4]

Baden in the German Confederation

[edit]

In 1815 Baden became a member of the German Confederation established by the Act of 8 June, annexed to the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna of 9 June. However, in the haste of winding up the Congress, the question of the succession to the grand duchy did not get settled, a matter that would soon become acute.[4]

The treaty of 16 April 1816, by which the territorial disputes between Austria and Bavaria were settled, also supported Bavaria's claim to the Palatine parts of Baden on the east bank of the Rhine and reaffirmed the succession rights of King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and his House of Palatinate-Birkenfeld to all of Baden, upon the expected event of the extinction of the House of Zähringen. As a counter to this, in 1817, the Grand Duke Charles issued a pragmatic sanction (Hausgesetz) declaring the counts of Hochberg, the issue of a morganatic marriage between the Grand Duke Charles Frederick and Luise Geyer von Geyersberg (created countess Hochberg), capable of succeeding to the crown. A controversy between Bavaria and Baden ensued, which was only decided in favour of the Hochberg claims by a treaty signed by Baden and the four great powers at Frankfurt on 10 July 1819.[4]

Meanwhile, the dispute had wide-ranging effects. In order to secure popular support for the Hochberg heir, in 1818 Grand Duke Charles granted to the grand duchy, under Article XIII of the Act of Confederation, a liberal constitution, under which two chambers were constituted and their assent declared necessary for legislation and taxation. The outcome was important far beyond the narrow limits of the duchy, as all of Germany watched the constitutional experiments in the southern states.[4]

In Baden, the conditions were not favourable for success. During the revolutionary period, the people had fallen completely under the influence of French ideas, and this was sufficiently illustrated by the temper of the new chambers, which tended to model their activity on the proceedings of the National Convention (1792–1795) in the earlier days of the French Revolution. Additionally, the new Grand Duke Louis I (ruled 1818–1830), who had succeeded in 1818, was unpopular, and the administration was in the hands of hide-bound and inefficient bureaucrats.[4]

The result was a deadlock. Even before the promulgation of the Carlsbad Decrees in October 1819, the grand duke had prorogued the chambers after three months of unproductive debate. The reaction that followed was as severe in Baden as elsewhere in Germany, and culminated in 1823 when, on the refusal of the chambers to vote on the military budget, the grand duke dissolved them and levied the taxes on his own authority. In January 1825, owing to official pressure, only three Liberals were returned to the chamber. A law was passed making the budget presentable only every three years, and the constitution ceased to have any active existence.[4]

In 1830 Grand Duke Louis was succeeded by his half-brother Grand Duke Leopold (ruled 1830–1852), the first of the Höchberg line. The July Revolution (1830) in France did not cause any disturbances in Baden, but the new grand duke showed liberal tendencies from the beginning. The elections of 1830 proceeded without interference, and resulted in the return of a Liberal majority. The next few years saw the introduction, under successive ministries, of liberal reforms in the constitution, in criminal and civil law, and in education. In 1832, the adhesion of Baden to the Prussian Zollverein did much for the material prosperity of the country.[4]

1849 Baden Revolution

[edit]By 1847, radicalism once more began to raise its head in Baden. On 12 September 1847, a popular demonstration held at Offenburg passed resolutions demanding the conversion of the regular army into a national militia, which should take an oath to the constitution, as well as a progressive income tax, and a fair adjustment of the interests of capital and labour.[4]

The news of the revolution of February 1848 in Paris brought agitation to a head. Numerous public meetings were held and the Offenburg programme was adopted. On 4 March 1848, under the influence of popular excitement, the lower chamber accepted this programme almost unanimously. As in other German states, the government bowed to the storm, proclaimed an amnesty and promised reforms. The ministry remodelled itself in a more liberal direction, and sent a new delegate to the federal diet at Frankfurt, empowered to vote for the establishment of a parliament for a united Germany.[4]

Disorder, fomented by republican agitators, continued nonetheless. The efforts of the government to suppress the agitators with the aid of federal troops led to an armed insurrection, which was mastered without much difficulty. The uprising, led by Friedrich Hecker, Gustav Struve and others, was lost at Kandern on 20 April 1848. Freiburg, which they held, fell on 24 April and, on 27 April, a Franco–German legion, which had invaded Baden from Strasbourg, was routed at Dossenbach.[4]

In the beginning of 1849, however, the issue of a new constitution in accordance with the resolutions of the Frankfurt parliament, led to more serious trouble. It did little to satisfy the radicals, angered by the refusal of the second chamber to agree to their proposal for the summoning of a constituent assembly on 10 February, 1849.[4]

The new insurrection that broke out proved a more formidable affair than the first. A military mutiny at Rastatt on 11 May showed that the army sympathised with the revolution, which was proclaimed two days later at Offenburg amid tumultuous scenes. Also, on 13 May a mutiny at Karlsruhe forced Grand Duke Leopold to flee, and the next day his ministers followed. Meanwhile, a committee of the diet under Lorenz Brentano (1813–1891), who represented the more moderate radicals against the republicans, established itself in the capital in an attempt to direct affairs pending the establishment of a provisional government.[4]

This was accomplished on 1 June and, on 10 June, the constituent diet, consisting entirely of the most "advanced" politicians, assembled. It had little chance of doing more than make speeches. The country remained in the hands of an armed mob of civilians and mutinous soldiers. Meanwhile, the Grand Duke of Baden had joined with Bavaria in requesting the armed intervention of Prussia, which Berlin granted on the condition that Baden would join the Alliance of the Three Kings.[4]

From this moment, the revolution in Baden was doomed, and with it the revolution across Germany. The Prussian Army, under Prince William (afterwards William I, German Emperor), invaded Baden in the middle of June 1849.[4] Afraid of a military escalation, Brentano reacted hesitantly – too hesitantly for the more radical Gustav Struve and his followers, who overthrew him and established a Pole, Ludwig Mieroslawski (1814–1878), in his place.

Mieroslawski reduced the insurgents to some semblance of order. On 20 June, 1849, he met the Prussians at Waghausel, and suffered complete defeat. On 25 June, Prince William entered Karlsruhe and, at the end of the month, the members of the provisional government, who had taken refuge at Freiburg, dispersed. The insurgent leaders who were caught, notably the ex-officers, suffered military execution. The army was dispersed among Prussian garrison towns, and Prussian troops occupied Baden for a time.[4] In the months following, no fewer than 80,000 people left Baden for America.[6] Many of these migrants would later participate in the American Civil War as abolitionists and union soldiers.[7]

Grand Duke Leopold returned on 10 August and at once dissolved the diet. The following elections resulted in a majority favourable to the new ministry, which passed a series of laws of a reactionary tendency with a view to strengthening the government.[4]

Towards the German Empire

[edit]Grand Duke Leopold died on 24 April 1852 and was succeeded by his second son, Frederick, as regent, since the eldest, Louis II, Grand Duke of Baden (died 22 January 1858), was incapable of ruling. The internal affairs of Baden during the period that followed have little general interest.

Grand Duke Frederick I (ruled 1856–1907) opposed the war with Prussia from the first, but yielded to popular resentment at the policy of Prussia on the Schleswig-Holstein question. The ministry, as one, resigned. In the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Austria's contingents, under Prince William, had two sharp engagements with the Prussian Army of the Main. However, on 24 July 1866, two days before the Battle of Werbach, the second chamber petitioned the grand duke to end the war and enter into an offensive and defensive alliance with Prussia.[4]

Baden announced her withdrawal from the German Confederation and, on 17 August 1866, signed a treaty of peace and alliance with Prussia. Bismarck himself resisted the adhesion of Baden to the North German Confederation. He had no wish to give Napoleon III a good excuse for intervention, but the opposition of Baden to the formation of a South German confederation made the union inevitable. The Baden army took a conspicuous share in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and it was Grand Duke Frederick of Baden, who, in the historic assembly of the German princes at Versailles, was the first to hail the king of Prussia as German Emperor.[4]

Kulturkampf

[edit]The internal politics of Baden, both before and after 1870, centered in the main around the question of religion. The signing on 28 June 1859 of a concordat with the Holy See, which placed education under the oversight of the clergy and facilitated the establishment of religious institutes, led to a constitutional struggle. This struggle ended in 1863 with the victory of secular principles, making the communes responsible for education, though admitting the priests to a share in the management. The quarrel between secularism and Catholicism, however, did not end. In 1867, on the accession to the premiership of Julius von Jolly (1823–1891), several constitutional changes in a secular direction occurred: responsibility of ministers, freedom of the press, and compulsory education. On 6 September 1867, a law compelled all candidates for the priesthood to pass government examinations. The archbishop of Freiburg resisted, and, on his death in April 1868, the see remained vacant.[4]

In 1869, the introduction of civil marriage did not allay the strife, which reached its climax after the proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility in 1870. The Kulturkampf raged in Baden, as in the rest of Germany, and, here as elsewhere, the government encouraged the formation of Old Catholic communities. Not until 1880, after the fall of the ministry of Jolly, did Baden reconcile with Rome. In 1882 the archbishopric of Freiburg was again filled.[4]

In the German Empire

[edit]The political tendency of Baden, meanwhile, mirrored that of all Germany. In 1892 the National Liberals had a majority of just one in the diet. From 1893, they could stay in power only with the aid of the Conservatives and, in 1897, a coalition of the Catholic Centre Party, Socialists, Social Democrats and Radicals (Freisinnige) won a majority for the opposition in the chamber.[4]

Amid all these contests, the statesmanlike moderation of Grand Duke Frederick won him universal esteem. By the treaty under which Baden had become an integral part of the German Empire in 1871, he had reserved only the exclusive right to tax beer and spirits. The army, the post office, railways and the conduct of foreign relations passed to the effective control of Prussia.[4]

In his relations with the German Empire, too, Frederick proved himself more of a great German noble than a sovereign prince actuated by particularist ambitions. His position as husband of the Emperor William I's only daughter, Louise (whom he had married in 1856), gave him a peculiar influence in the councils of Berlin. When, on 20 September 1906, the Grand Duke celebrated at once the jubilee of his reign and his golden wedding anniversary, all Europe honoured him. King Edward VII appointed him, by the hands of the Duke of Connaught, a Knight of the Order of the Garter. But more significant, perhaps, was the tribute paid by Le Temps, the leading Parisian paper:[4]

Nothing more clearly demonstrates the sterile paradox of the Napoleonic work than the history of the Grand Duchy. It was Napoleon, and he alone, who created this whole state in 1803 to reward in the person of the little margrave of Baden a relative of the emperor of Russia. It was he who after Austerlitz aggrandized the margravate at the expense of Austria; transformed it into a sovereign principality and raised it to a Grand Duchy. It was he too who, by the secularization on the one hand and by the dismemberment of Württemberg on the other, gave the Grand Duke 500,000 new subjects. He believed that the recognition of the prince and the artificial ethnical formation of the principality would be pledges of security for France. But in 1813 Baden joined the coalition, and since then that nation created of odds and ends (de bric et de broc) and always handsomely treated by us, had not ceased to take a leading part in the struggles against our country. The Grand Duke Frederick, Grand Duke by the will of Napoleon, has done France all the harm he could. But French opinion itself renders justice to the probity of his character and to the ardour of his patriotism, and nobody will feel surprise at the homage with which Germany feels bound to surround his old age.[4]

Grand Duke Frederick I died at Mainau on 28 September 1907. He was succeeded by his son, Grand Duke Frederick II[4] (ruled 1907–1918, died 1928). His wife, Princess Hilda of Nassau, was popular due her supports of artistic endeavors and treatment of the wounded soldiers during World War I.[8]

22,000 industrial workers in Mannheim went on strike in January 1918.[9] Members of the garrisons of Lahr and Offenburg formed a soldiers' council on 8 November 1918. Wilhelm Engelbert Oeftering stated that a member of Replacement Battalion 171 who returned from Kiel initiated the demonstration. Another soldiers' council was formed in Mannheim on 9 November.[10]

The NLP, Centre, and Progressive (FVP) parties requested President Heinrich Bodman's resignation on 9 November, due to fears that violence would break out in Mannheim. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated the same day while the mayors of Mannheim and Karlsruhe formed Welfare Committees. The Karlsruhe Welfare Committee and Soviets formed a provisional government, with Bodman's recognition, on 10 November. Five SPD members, two Independent Social Democrats, two Centrists, and two National Liberals made up the government. Anton Geiss, the chair of the SPD in Baden and vice-president of the Landtag, chaired the provisional government.[11][12][13]

From 10 to 14 November, soldiers' councils called for the government to declare a republic and remove Frederick II. Frederick II called this government unconstitutional, but did not contest it and dismissed his ministers. He renounced his governmental powers on 13 November, and abdicated on 22 November, ending 600 years of rule by the House of Zähringen. He was one of the last German monarchs to abdicate.[14][11] The Free People's Republic of Baden was formed on 14 November, and elections scheduled on 5 January 1919.[15]

Legacy

[edit]After World War II the French military government created the State of Baden, at first called South Baden, out of the southern half of the former duchy, with Freiburg as its capital; this area was declared in its 1947 constitution to be the true successor of the duchy. The northern half was combined with northern Württemberg, becoming part of the American-occupied zone and forming the state of Württemberg-Baden. Both Baden and Württemberg-Baden became states of West Germany upon the latter's formation in 1949, but in 1952 they merged with each other and with Württemberg-Hohenzollern, which was southern Württemberg and a former Prussian exclave, to form Baden-Württemberg – still the only merger of states to have taken place in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Constitution and government

[edit]A constitution was adopted on 25 August 1818, and existed with some changes until the end of the duchy.[16] The Grand Duchy of Baden was a hereditary monarchy with executive power vested in the Grand Duke; legislative authority was shared between him and a representative assembly (Landtag) consisting of two chambers.[4]

The upper chamber included all the princes of the ruling family of full age, the heads of all the mediatized families, the Archbishop of Freiburg, the president of the Protestant Evangelical Church of Baden, a deputy from each of the universities and the technical high school, eight members elected by the territorial nobility for four years, three representatives elected by the chamber of commerce, two by that of agriculture, one by the trades, two mayors of municipalities, and eight members (two of them legal functionaries) nominated by the Grand Duke.[4]

The lower chamber consisted of 73 popular representatives, of whom 24 were elected by the burgesses of certain communities, and 49 by rural communities. Every citizen of 25 years of age, who had not been convicted and was not a pauper, had a vote. The elections were, however, indirect. The citizens selected the Wahlmänner (deputy electors), the latter selecting the representatives. The chambers met at least every two years. The lower chambers were elected for four years, half the members retiring every two years.[4]

The executive consisted of four departments: the interior, foreign and grand-ducal affairs; finance; justice; and ecclesiastical affairs and education.[4]

The chief sources of revenue were direct and indirect taxes, the railways and domains. The railways were operated by the state, and formed the only source of major public debt, about 22 million pounds sterling.[4]

The supreme courts lay in Karlsruhe, Freiburg, Offenburg, Heidelberg, Mosbach, Waldshut, Konstanz, and Mannheim, from which appeals passed to the Reichsgericht (the supreme tribunal) in Leipzig.[4]

Population

[edit]At the beginning of the 19th century, Baden was a margraviate, with an area of barely 1,300 sq mi (3,400 km2) and a population of 210,000. Subsequently, the grand duchy acquired more territory so that, by 1905, it had 5,823 sq mi (15,082 km2)[17] and a population of 2,010,728.[17] Of that number, 61% were Roman Catholics, 37% Protestants, 1.5% Jews, and the remainder of other religions. At that time, about half of the population was rural, living in communities of less than 2,000; the density of the rest was about 330/sq mi (130/km2).[4]

The country was divided into the following districts:[4]

- Mannheim district had the towns Mannheim, and Heidelberg

- Karlsruhe district included Karlsruhe and Pforzheim

- Freiburg im Breisgau district included Freiburg

- Konstanz district had Konstanz

The capital of the duchy was Karlsruhe, and important towns other than those listed included Rastatt, Baden-Baden, Bruchsal, Lahr and Offenburg. The population was most thickly clustered in the north and near the Swiss city of Basel. The inhabitants of Baden are of various origins, those to the south of Murg being descended from the Alemanni and those to the north from the Franks, while the Swabian Plateau derives its name from the adjacent German tribe (Schwaben),[4] who lived in Württemberg.

Geography

[edit]

The grand duchy had an area of 15,081 km2 (5,823 sq mi)[17] and consisted of a considerable portion of the eastern half of the fertile valley of the Rhine and of the mountains which form its boundary.[4]

The mountainous part was by far the most extensive, forming nearly 80% of the whole area. From Lake Constance in the south to the river Neckar in the north is a portion of the Black Forest (German: Schwarzwald), which is divided by the valley of the Kinzig into two districts of different elevation. To the south of the Kinzig the mean height is 945 m (3,100 ft)), and the highest summit, the Feldberg, reaches about 1,493 m (4,898 ft), while to the north the mean height is only 640 metres (2,100 ft), and the Hornisgrinde, the culminating point of the whole, does not exceed 1,164 metres (3,819 ft). To the north of the Neckar is the Odenwald Range, with a mean of 439 metres (1,440 ft), and in the Katzenbuckel, an extreme of 603 metres (1,978 ft). Lying between the Rhine and the Dreisam is the Kaiserstuhl, an independent volcanic group, nearly 16 km in length and 8 km in breadth, the highest point of which is 536 metres (1,759 ft).[4]

The greater part of Baden belongs to the basin of the Rhine, which receives upwards of twenty tributaries from the highlands; the north-eastern portion of the territory is also watered by the Main and the Neckar. A part, however, of the eastern slope of the Black Forest belongs to the basin of the Danube, which there takes its rise in a number of mountain streams. Among the numerous lakes which belonged to the duchy are the Mummelsee, Wildersee, Eichenersee and Schluchsee, but none of them is of any significant size. Lake Constance (Bodensee) belongs partly to the German federal states (Länder) of Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria, and partly to Austria and Switzerland.[4]

Owing to its physical configuration, Baden presents great extremes of heat and cold. The Rhine valley is the warmest district in Germany, but the higher elevations of the Black Forest record the greatest degrees of cold experienced in the south. The mean temperature of the Rhine valley is approximately 10 °C (50 °F) and that of the high table-land 6 °C (43 °F). July is the hottest month and January the coldest.[4]

The mineral wealth of Baden was not great, but iron, coal, lead and zinc of excellent quality were produced; silver, copper, gold, cobalt, vitriol and sulfur were obtained in small quantities. Peat was found in abundance, as well as gypsum, china clay, potter's earth and salt. The mineral springs of Baden are still very numerous and have acquired great celebrity, those of Baden-Baden, Badenweiler, Antogast, Griesbach, Friersbach and Peterthal being the most frequented.[4]

In the valleys the soil is particularly fertile, yielding luxuriant crops of wheat, maize, barley, spelt, rye, beans, potatoes, flax, hemp, hops, beetroot and tobacco; and even in the more mountainous part, rye, wheat and oats are extensively cultivated. There is a considerable extent of pasture-land, and the rearing of cattle, sheep, pigs and goats is extensively practised. Of game, deer, boar, snipe and wild partridges are fairly abundant, while the mountain streams yield trout of excellent quality. Viticulture is increasing, and the wines continue to sell well. The Baden wine region is Germany's third largest in terms of vineyard surface. The gardens and the orchards supply an abundance of fruit, especially sweet cherries, plums, apples and walnuts, and bee-keeping is practised throughout the country. A greater proportion of Baden than any other south German state is occupied by forests. In these, the predominant trees are European beech and silver fir, but many others, such as sweet chestnut, Scots pine, Norway spruce and the exotic coast Douglas-fir, are well represented. A third, at least, of the annual timber production is exported.[4]

Industries

[edit]Around 1910, 56.8% of the region's land mass was cultivated and 38% was forested. Before 1870, the agricultural sector was responsible for the bulk of the grand duchy's wealth, but this was superseded by industrial production. The chief products were machinery, woollen and cotton goods, silk ribbons, paper, tobacco, china, leather, glass, clocks, jewellery, and chemicals. Beet sugar was also manufactured on a large scale, as were wooden ornaments and toys, music boxes and organs.[4]

The exports of Baden consisted mostly of the above goods and were considerable, but the bulk of its trade consisted of transit. The grand duchy had many railways and roads,[4] as well as the Rhine for transporting goods by ship. Railways were run by the state as the Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway (Großherzoglich Badische Staatseisenbahnen). A rail-line ran mostly parallel with the Rhine, with oblique branches from East to West.

Mannheim was the great market centre for exports down the Rhine and had substantial river traffic. It was also the chief manufacturing town for the duchy and an important administrative centre for its northern region.[4]

Education and religion

[edit]There were numerous educational institutions in Baden. There were three universities, one Protestant in Heidelberg, one Roman Catholic in Freiburg im Breisgau, and a research university in Karlsruhe.

The grand-duke was a Protestant; under him, the Evangelical Church was governed by a nominated council and a synod consisting of a prelate, 48 elected and 7 nominated lay and clerical members. The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Freiburg is Metropolitan of the Upper Rhine.[4]

Leaders

[edit]Grand Dukes (1806–1918)

[edit]- 1806–1811: Charles Frederick (1728–1811)

- 1811–1818: Charles (1786–1818)

- 1818–1830: Louis I (1763–1830)

- 1830–1852: Leopold (1790–1852)

- 1852–1858: Louis II (1824–1858)

- 1858–1907: Frederick I (1826–1907), (since 1852 Regent, since 1856 with the title Grand Duke)

- 1907–1918: Frederick II (1857–1928)

Ministers-President (1809–1918)

[edit]- 1809–1810: Sigismund von Reitzenstein

- 1810–1810: Conrad Karl Friedrich von Andlau-Birseck

- 1810–1812: Christian Heinrich Gayling von Altheim

- 1812–1817: Karl Christian von Berckheim

- 1817–1818: Sigismund von Reitzenstein

- 1818–1831: Wilhelm Ludwig Leopold Reinhard von Berstett

- 1832–1833: Sigismund von Reitzenstein

- 1833–1838: Ludwig Georg von Winter

- 1838–1839: Karl Friedrich Nebenius

- 1839–1843: Friedrich Landolin Karl von Blittersdorf

- 1843–1845: Christian Friedrich von Boeckh

- 1845–1846: Karl Friedrich Nebenius

- 1846–1848: Johann Baptist Bekk

- 1848–1849: Karl Georg Hoffmann

- 1849–1850: Friedrich Adolf Klüber

- 1850–1856: Ludwig Rüdt von Collenberg-Bödigheim

- 1856–1860: Franz von Stengel

- 1861–1866: Anton von Stabel

- 1866–1868: Karl Mathy

- 1868–1876: Julius Jolly

- 1876–1893: Ludwig Karl Friedrich Turban

- 1893–1901: Franz Wilhelm Nokk

- 1901–1905: Carl Ludwig Wilhelm Arthur von Brauer

- 1905–1917: Alexander von Dusch

- 1917–1918: Heinrich von Bodman

See also

[edit]- Baden (territory)

- Baden Army

- German Revolution of 1918–1919

- November 1918 in Alsace-Lorraine

- Bavarian Soviet Republic

References

[edit]- ^ "Baden". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ^ Edmund C. Clingan (2010). The Lives of Hans Luther, 1879 - 1962: German Chancellor, Reichsbank President, and Hitler's Ambassador. Lexington Books. p. 142.

- ^ "The Salmen – a monument of national significance".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baden, Grand Duchy of". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (2016). The Pursuit of Power ((paperback) ed.). Penguin Books. p. 212. ISBN 9780143110422.

- ^ Lonn, Ella (1950). "VII. The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War". In Zucker, A. E. (ed.). The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the German Revolution of 1848 (Reissued, 1967, by Russell & Russell ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. LCCN 66-27186.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 123.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 100-102.

- ^ a b Exner 2016, p. 291-294.

- ^ Grill 1983, p. 15-16.

- ^ Engehausen, Frank. "Novemberrevolution im Südwesten". State Center for Political Education Baden-Württemberg. Archived from the original on 1 February 2024.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 123-127.

- ^ Grill 1983, p. 16.

- ^ Schmidgall 2012, p. 19.

- ^ a b c "Baden". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

Works cited

[edit]- Exner, Konrad (2016). "Die politischen und wirtschaftlichen Ereignisse der Republik Baden in der Zeit der Weimarer Republik". Badische Heimat. 96 (2). Landesverein Badische Heimat: 291–300.

- Grill, Johnpeter (1983). The Nazi Movement in Baden, 1920-1945. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807814725.

- Schmidgall, Markus (2012). Die Revolution 1918/19 in Baden. Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. ISBN 9783866447271.

Further reading

[edit]- Grill, Johnpeter Horst. The Nazi Movement in Baden, 1920–1945 (Univ of North Carolina Press, 1983).

- Lee, Loyd E. The Politics of Harmony: Civil Service, Liberalism, and Social Reform in Baden, 1800–1850 (University of Delaware Press, 1980).

- Liebel, Helen P. "Enlightened bureaucracy versus enlightened despotism in Baden, 1750–1792." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 55.5 (1965): 1–132.

- Selgert, Felix. "Performance, pay and promotion: implementing a Weberian bureaucracy in nineteenth century Baden." Cliometrica 8.1 (2014): 79–113.

- Tuchman, Arleen. Science, Medicine, and the State in Germany: The Case of Baden, 1815–1871 (Oxford University Press, 1993).

In German

[edit]- Schwarzmaier, Hansmartin, ed. Geschichte Badens in Bildern, 1100–1918 (Kohlhammer, 1993), heavily illustrated history.

- Grand Duchy of Baden

- History of Baden

- Former states and territories of Baden-Württemberg

- Former grand duchies

- States of the German Empire

- States of the German Confederation

- States of the Confederation of the Rhine

- States and territories established in 1806

- States and territories disestablished in 1918

- 1806 establishments in the Confederation of the Rhine

- 1918 disestablishments in Germany

- Modern history of Germany