British Aerospace 146

| BAe 146 / Avro RJ | |

|---|---|

| |

A Lufthansa Avro RJ85 (ex BAe-146-200), the midsize variant | |

| General information | |

| Type | Regional Jet Airliner |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | British Aerospace BAE Systems Avro International |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Mahan Air |

| Number built | 394 (BAe 146: 221; Avro RJ: 170; Avro RJX: 3) |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1983–2001 |

| Introduction date | May 1983 |

| First flight | 3 September 1981 |

The British Aerospace 146 (also BAe 146) is a short-haul and regional airliner that was manufactured in the United Kingdom by British Aerospace, later part of BAE Systems. Production ran from 1983 until 2001. Avro International Aerospace manufactured an improved version known as the Avro RJ. Production for the Avro RJ version began in 1992. Later on, a further-improved version with new engines, the Avro RJX, was announced in 1997, but only two prototypes and one production aircraft were built before production ceased in 2001. With 387 aircraft produced, the Avro RJ/BAe 146 is the most successful British civil jet airliner program.[1]

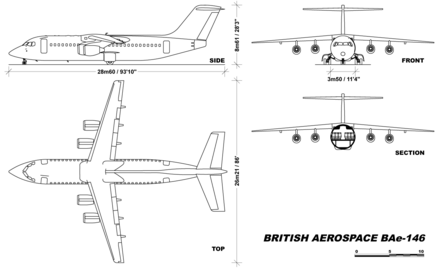

The BAe 146/Avro RJ is a high-wing cantilever monoplane with a T-tail. It has four geared turbofan engines mounted on pylons underneath the wings, and has a retractable tricycle landing gear. The aircraft operates very quietly, and as such has been marketed under the name Whisperjet.[2] It sees wide usage at small, city-based airports such as London City Airport. In its primary role, it serves as a regional jet, short-haul airliner, or regional airliner, while examples of the type are also in use as private jets.

The BAe 146 was produced in -100, -200 and -300 models. The equivalent Avro RJ versions are designated RJ70, RJ85, and RJ100. The freight-carrying version carries the designation "QT" (Quiet Trader), and a convertible passenger-or-freight model is designated as "QC" (Quick Change). A "gravel kit" can be fitted to aircraft to enable operations from rough, unprepared airstrips.[3]

Development

[edit]Origins

[edit]

In August 1973, Hawker Siddeley launched a new 70-seat regional airliner project, the HS.146, to fill the gap between turboprop-powered airliners such as the Hawker Siddeley HS.748 and the Fokker F27 Friendship and small jet airliners such as the BAC One-Eleven and Boeing 737.[4][5] The concept of a feeder jet had, however, been "one of the many speculative ideas on the drawing boards of British aircraft manufacturers" as far back as 1958.[6]

The chosen configuration had a high wing and a T-tail to give good short-field performance, while the aircraft was to be powered by four 6,500 lbf thrust Avco Lycoming ALF 502H turbofan engines. There were several reasons why a twin engine configuration was not chosen,[7] this being a controversial decision for a relatively small aircraft and dictated by the choice of engine which, despite its "rugged, quiet and fuel efficient" characteristics, needed to be deployed in a four-engine configuration to provide the power and range required by the concept. Such a configuration was considered by British Aerospace to be advantageous in the event of a single engine failure, offering "exceptional three-engine performance" that would appeal to operators in mountainous environments and from "high, hot or poor grade airfields".[6]

The programme was initially launched with backing from the UK government, which agreed to contribute 50% of the development costs in return for a share of the revenues from each aircraft sold.[8] In October 1974, all work on the project was halted as a result of the world economic downturn resulting from the 1973 oil crisis.[9][10][11]

Low-key development proceeded, however, and in 1978, British Aerospace, Hawker Siddeley's corporate successor, relaunched the project. British Aerospace marketed the aircraft as a quiet, low-consumption, turbofan aircraft, which would be effective at replacing the previous generation of turboprop-powered feeder aircraft.[5] The first order for the BAe 146 was placed by Líneas Aéreas Privadas Argentinas in June 1981. Prior to the first flight, British Aerospace had forecast that the smaller 146-100 would significantly outsell the 146-200 variant; however, airlines showed a higher level of interest in the larger 146-200.[12]

By 1981, a large assembly line had been completed at British Aerospace's Hatfield site,[12] and the first completed aircraft flew that year, quickly followed by two more prototypes.[4][13] By then, the unit cost of the 146-200 was £11 million,[12] and the program cost was £350 million.[14] Initial flight results showed better-than-predicted takeoff and climb performance.[13] In 1982, British Aerospace stated that the sale of a total 250 aircraft was necessary for the venture to break even.[13] The BAe 146 received its Certificate of Airworthiness on 8 February 1983.[15] Upon its launch into service, it was hailed as being "the world's quietest jetliner".[16]

Production

[edit]

Early production aircraft were built at Hatfield, which had originally been a de Havilland factory. The Avro RJ family of aircraft was assembled at the Avro International (BAE Systems Regional Aircraft Centre) at Woodford Aerodrome in Greater Manchester, England. Production of various sections of the aircraft was carried out at different BAE plants: the rear fuselage section was manufactured at the former Avro site at Chadderton, Greater Manchester; the centre fuselage section was manufactured at Filton; the vertical stabilizer came from Brough; the engine pylons were made at Prestwick;[17] and the nose section was manufactured at Hatfield, where the assembly line for the early aircraft was located. Some manufacturing was subcontracted outside the UK; the wings were made by Textron in the United States and the tailplane and control surfaces were made by Saab-Scania in Sweden.[18][19]

Due to the sales performance of the BAe 146, British Aerospace announced a development project in early 1991 to produce a new variant of the type, powered by two turbofan engines instead of four, that was offered to airlines as a regional jet aircraft. Dubbed the new regional aircraft (NRA), other proposed alterations from the BAe 146 included the adoption of a new enlarged wing and a lengthened fuselage.[20]

In 1993, the upgraded Avro RJ series superseded the BAe 146. Changes included the replacement of the original Lycoming ALF 502 turbofan engines by higher-thrust LF 507 turbofan engines, which were housed in redesigned nacelles. The Avro RJ series also featured a modernised cockpit with EFIS replacing the analogue ADI, HSI, and engine instrumentation.[21] An arrangement between British Aerospace and Khazanah Nasional would have opened an Avro RJ production line in Malaysia, but this deal collapsed in 1997.[22]

In 2000, British Aerospace announced that it was to replace the Avro RJ series with a further-improved Avro RJX series, however on 27 November 2001 BAE announced the cancellation of the RJX programme as part of the closure of its regional aircraft business. BAE also announced 1,669 job losses and a £400m charge as part of the decision.[23] The Financial Times stated that BAE had "draw[n] a line under a business that once threatened to destroy the whole group. In 1992, the regional aircraft operation blew a hole in the then British Aerospace's balance sheet, forcing it to take a £1bn write-off."[24]

Production of the Avro RJ ended with the final four aircraft being delivered in late 2003; a total of 173 Avro RJ aircraft were delivered between 1993 and 2003.[22]

Design

[edit]Overview

[edit]

British Aerospace promoted the BAe 146 to airlines as a "feederliner" and short-haul regional airliner.[12] The airframe of the aircraft and many other key areas were designed to be as simple as possible. The engines lack thrust reversers due to their perceived reduced effectiveness in anticipated conditions. Instead, the BAe 146 features a large airbrake with two petals below the tail rudder at the rear of the fuselage, which has the advantage of being usable during flight and allowing for steep descent rates if required.[25] In addition, the aircraft has full-width wing spoilers, which are deployed immediately on landing.

The aircraft proved to be useful on "high-density" regional and short-haul routes. In economy class, the BAe 146 can either be configured in a standard five-abreast layout or a high-density six-abreast layout, making it one of few regional jets that can use a six-abreast layout in economy class.[21] Reportedly, the aircraft is profitable on most routes with only marginally more than half the seats occupied.[5]

The BAe 146 is also renowned for its relatively quiet operation, a positive feature that appealed to those operators that wanted to provide services to noise-sensitive airports within cities.[21][26] The aircraft is one of only a few types that can be used on flights to London City Airport, which has a steep approach and short runway; for several years, the BAe 146 was the only conventional jet aircraft capable of flying from London City Airport.[27][28]

Features

[edit]

According to the BAe 146's chief designer, Bob Grigg, making the aircraft as easy to maintain as possible and keeping operators' running costs as low as possible were considered high priorities from the start of the design process.[29] Grigg highlighted factors such as design simplicity, using off-the-shelf components where possible, and the internal use of firm cost targets and continuous monitoring. British Aerospace also adopted a system of cost guarantees between component suppliers and the operators of the BAe 146 to enforce stringent requirements.[30]

Drawing on experience from the Hawker Siddeley Trident and the Airbus A300, both the fuselage and wing were carefully designed for a reduced part-count and complexity.[31] A high-mounted wing was adopted with an uninterrupted top surface; the BAe 146's wing did not make use of leading-edge extensions, which also enabled a simplified fixed tailplane.[32] The undercarriage of the aircraft is toughened to resist damage and stability is maximised by the placement of landing gear, of particular value when operating from rough airstrips.[14]

The engines are not fitted with thrust reversers, instead the aircraft has a clamshell air brake in the tail and full width spoilers on the wings.

The BAe 146 was the second aircraft, after the Concorde, to use carbon brakes.[14] The aircraft features a low amount of composite material, used in parts of the secondary structure only.[31] Initial production aircraft featured a conventional cockpit and manual flight controls.[25] At launch, the onboard auxiliary power unit consumed only half the fuel and weighed only a third as much as other contemporary models.[31]

The aircraft can be fitted with auxiliary fuel tanks to extend its range. So-called "pannier tanks" fit in the inner wing either side of the fuselage, while more tankage can be fitted in the under-floor baggage compartment, fore and aft of the undercarriage bay.[33]

Engines

[edit]

The BAe 146 is a quadjet powered by four Avco Lycoming ALF 502 turbofan engines, which are fixed on pylons underneath the aircraft's high wing.[4] The ALF 502 was derived from the Lycoming T55 turboshaft powerplant that powers the Chinook heavy-transport helicopter. Notably, the BAe 146 has a very low level of operational noise, much lower than most competing aircraft. This was achieved largely through the use of the geared turbofan ALF 502; the gearbox allows the fan blade tip speed to stay below the speed of sound, dramatically reducing the aircraft's noise. Additionally, other sound-deadening measures include a high bypass ratio compared to contemporary aircraft and additional sound-damping layers built into the engine.[5]

Early on, the decision to adopt four engines for a feeder airliner rather than two was viewed as atypical by some commentators. Advantages of adopting the four-engine configuration include greater redundancy and superior takeoff performance from short runways, as well as in hot and high conditions.[4] Electrical power is primarily provided by generators located on each of the outboard engines.[21] For ease of maintenance and reduced operator costs, the ALF 502 is of a modular design and makes minimum use of specialist tooling.[34]

The ALF 502 has experienced multiple issues. Its internal electronics could overheat, triggering an automatic shutdown of an engine with no option for inflight restart, and certain rare atmospheric conditions could cause a loss of engine thrust due to internal icing.[35] Additionally, the BAe 146 experienced some issues with its bleed air and cabin pressurization systems, leading to a number of fume events where irritant fumes were introduced into the cabin by the pressurizing system.[36][37]

Operational history

[edit]

In May 1983, British airline Dan-Air became the first carrier to launch services using British Aerospace's new 146; the first revenue-earning service was flown between London Gatwick Airport and Bern Airport.[38] On 1 July 1984, the first of 20 BAe 146s ordered by Pacific Southwest Airlines was officially delivered.[39] Air Wisconsin was another major US operator of the 146, replacing their fleet of turboprop Fokker F27 Friendships with the type.[40] In 1985, Aspen Airways inaugurated the first scheduled jet service into Aspen, Colorado, in the Rocky Mountains of the western U.S. with a BAe 146-100 operating from an airfield with an elevation of 7,820 feet. The BAe 146 was announced in January 1987 to have been selected to launch the first jet services from London City Airport; it was chosen due to its unmatched flying characteristics and ability to operate from so-called STOLports.[41]

The 146 was introduced into Royal Air Force service in 1986 until 2022 as a VIP transport and was operated by 32 (The Royal) Squadron.[42] According to Flight International, at least 25 executive aircraft have been produced for various customers; many of these had undergone conversions following airline operations.[43]

From the late 1980s until the early 2000s, the 146 was widely used for passenger services in Australia, where the type was suited to long-distance, low-volume routes; 18 were in service with Ansett Australia in 1999.[44] The BAe 146 was also operated by East-West, taking delivery of eight from 1990, until the company was absorbed into Ansett. National Jet Systems began operations under the Airlink brand on behalf of Australian Airlines (and later Qantas) in 1990, with Airlink's successor QantasLink continuing to use the type until 2005. In 2005, National Jet Systems transferred operations of the BAe 146 and Avro RJ fleet to its subsidiary National Jet Express, which continued to operate 15 aircraft of the type in varying specification for scheduled charter operations, and whose fleet included the second production airframe, a -100 model converted to QT specification, which first flew in January 1982 as part of the testing and certification program.[citation needed] National Jet Express ceased BAe 146 and Avro RJ passenger operations in June 2022 after 32 years[45] and having operated 33 different aircraft of the type.[46]

The initial customer for the BAe RJ85 series was Crossair, which took delivery of its first aircraft on 23 April 1993.[22]

Several major cargo operators have operated the type. As of 2012, the BAe 146 QT is the most numerous aircraft in TNT Airways's air freighter fleet.[47] In 2012, the Royal Air Force (RAF) announced it would acquire the BAe 146M as an interim transport aircraft between the retirement of the Lockheed C-130 Hercules and the introduction of the larger Airbus A400M Atlas, to supplement its air transport activities in Afghanistan.[42][48] In 2013, the RAF acquired two converted BAe146-200s, designated BAe146C Mk3, capable of carrying 10.6 tons of load, and fitted with a large 3.33- × 1.93-m side door.[49] The RAF also operates the BAe146 CC Mk2 in No. 32 Squadron RAF.[49]

At present, Pionair Australia, operates a mix of -200 and -300 BAe-146 aircraft, in both freight and passenger variants, on scheduled freight charters, ad-hoc passenger charter, and pre booked air tours around Australia, New Zealand, and the South Pacific. National Jet Express also continues to operate a fleet of BAe 146-300QT freighters on behalf of Qantas Freight, providing overnight services to and from curfew-restricted Sydney Airport under a type-specific exemption.[50]

On 3 May 2017, an Airlink Avro RJ85 made the first commercial airline flight in history to Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, a charter flight from Cape Town, South Africa, via Moçâmedes, Angola, to Saint Helena Airport to pick up passengers stranded when the island's only link with the outside world, the British Royal Mail Ship RMS St Helena, suffered propeller damage. The flight returned to Cape Town the same day with a stop at Windhoek, Namibia.[51] It was the only commercial flight ever made to Saint Helena until Airlink began the first scheduled commercial airline service in the island's history in October 2017.[52]

Variants

[edit]BAe 146-100 / Avro RJ70

[edit]

The first flight of the -100 occurred on 3 September 1981, with deliveries commencing in 1983.[53] The launch customer in March 1983 was Dan-Air. From 1986, The Queen's Flight of the RAF acquired a total of three 146-100s, designated BAe 146 CC2. These aircraft were fitted with a luxurious bespoke interior and operated in a VIP configuration with a capacity of 19 passengers and six crew. The BAe 146-100QC (Quick Change) is the convertible passenger/freight version and the BAe 146-100QT (Quiet Trader) is the freighter version.

The -100 was the last of the 146 series designs to be developed into the Avro RJ standard with first deliveries of the Avro RJ70 in late 1993. The RJ70 differed from the 146-100 in having LF 507 engines with FADEC and digital avionics. The RJ70 seats 70 passengers five abreast, 82 six abreast or 94 in high-density configuration.

BAe 146-200 / Avro RJ85

[edit]

The 146-200 features a 2.41-m (7 ft 11 in) fuselage extension and reduced cost per seat mile. The -200 first flew in August 1982 and entered service six months later. The BAe 146-200QC (Quick Change) is the convertible passenger/freight version and the BAe 146-200QT (Quiet Trader) is the freighter version. Two BAe 146-200QC aircraft, designated BAe 146 C3, were converted for the RAF, with infrared countermeasures systems and flare dispensers, for use in Afghanistan.[54]

The Avro RJ85, the first RJ development of the BAe 146 family, features an improved cabin and the more efficient LF 507 engines. Deliveries of the RJ85 began in April 1993. It seats up to 112 passengers.

BAe 146-300 / Avro RJ100

[edit]

British Aerospace announced its initial proposals for the -300 at the 1984 Farnborough Air Show. The aircraft's fuselage was to be stretched by 3.2 metres (10 ft 6 in) compared with the -200, allowing 122 passengers to be carried at 32-inch seat pitch and 134 at 29-inch seat pitch. More powerful (33 kilonewtons (7,500 lbf)) ALF 502R-7 engines would be used, and winglets were to be fitted to the aircraft's wingtips.[55][56] However, due to airlines favouring a lower initial price rather than minimising seat-mile costs, the definitive 146-300 emerged as a less extreme development. Ultimately, the fuselage was stretched by 2.34 metres (7 ft 8 in), giving a capacity of 100 passengers seated five-abreast at a 31-inch seat pitch, without winglets or the proposed ALF 502R-7.[57] Deliveries began in December 1988. A modified BAe 146-301 is used as the UK's Facility for Airborne Atmospheric Measurements. The BAe 146-300QC (Quick Change) is the convertible passenger/freight version and the BAe 146-300QT (Quiet Trader) is the freighter version.

The Avro RJ version of the 146-300, the second such development of the 146 product line, became the Avro RJ100. It shared the fuselage of the 146 version, but with interior, engine, and avionics improvements. The most common configuration in the RJ100 seats 100 passengers. An RJ115 variant, the same physical size, but with an increased MTOW and different emergency exits, was marketed, but never entered production;[58][59] it seated 116 as standard or up to a maximum of 128 in a high-density layout.

BAe 146STA

[edit]

Throughout the production life of the BAe 146, British Aerospace proposed a number of specialised military versions, including side- and rear-loading transports, an airborne tanker version,[60] and a carrier onboard delivery version.[61] Out of these proposals came the BAe 146STA (Sideloading Tactical Airlifter), based on the BAe 146QT cargo aircraft and sharing its cargo door on the left side of the rear fuselage. This military-transport version has a refuelling probe protruding from the nose; a demonstrator, fitted with a dummy refuelling probe and an air-openable paratroop door, was displayed at the 1989 Paris Air Show and carried out extensive demonstration tours, but no orders resulted.[62]

BAe 146M

[edit]BAE Systems announced the BAe 146M programme in 2009, designed to provide ex-civilian BAe 146-200 and -300 aircraft to military operators, available either in passenger or freighter configurations.[63] Upgrades and alterations made to the type include new glass cockpit avionics, additional fuel tanks, increased steep approach, and unpaved runway operation capabilities, and being outfitted with defensive aids; however, a rear cargo door was not introduced. BAE has stated that the 146M is suitable for performing airlift, medical evacuation, para-drop, surveillance, and inflight refueling operations.[64]

Avro RJX series

[edit]The RJX-70, RJX-85, and RJX-100 variants represented advanced versions of the Avro RJ Series. The RJX series used Honeywell AS977 turbofans for greater efficiency (15% less fuel burn, 17% increased range), quieter performance, and 20% lower maintenance costs.[65] Bhutan carrier Drukair ordered two RJX-85s, while British European placed firm orders for 12 RJX-100s and eight options.[66] However, BAE Systems terminated the project in November 2001, having completed and flown only three aircraft—a prototype each of the RJX-85 and RJX-100, and a production RJX-100 for British European. BAE reached an agreement with Druk Air and British European in early 2002 in which the airlines agreed not to enforce their firm orders for the RJX. BAE explored the possibility of manufacturing 14 "hybrid" aircraft, but British European at least was unwilling to accept the risk of operating a unique type.[67]

Firefighting air tanker conversions

[edit]

Firefighting air tanker versions of both the BAe 146 and the Avro RJ85 have been manufactured by the conversion of aircraft previously operated by airlines in scheduled passenger service.[68] Several organizations carry out such conversions, including U.S.-based Minden Air Corporation, Neptune Aviation Services, and Aero-Flite, a U.S. subsidiary of Canadian-based Conair Group.[69][70][71][72] In January 2012, Conair Group announced its arrangements to market and promote the Avro RJ85 as a major air tanker platform.[73] In October 2012, Air Spray Aviation of Alberta, Canada, purchased its first BAe 146 for conversion into an air tanker.[68] Air Spray purchased a second airframe for conversion in October 2013.[74]

According to the 3 April 2017, edition of SpeedNews-The Windshield, an on-line aviation publication, 14 BAE Systems-built BAe 146-200 and Avro RJ85 jets are in service in North America as aerial firefighting air tankers, with Conair flying seven Avro RJ85 aircraft and Neptune Aviation operating seven BAe 146-200 aircraft.[75] The article also states that Conair is converting an eighth Avro RJ85 for use as an air tanker, while Neptune is converting two more BAe 146-200s for aerial firefighting use. In addition, Air Spray is mentioned in this article as having acquired five BAe 146-200s for conversion to air tankers.

Airbus E-Fan X

[edit]The Airbus/Rolls-Royce/Siemens E-Fan X was a hybrid electric aircraft demonstrator being developed by a partnership of Airbus, Rolls-Royce plc and Siemens. Announced on 28 November 2017, it followed previous electric flight demonstrators towards sustainable transport for the European Commission's Flightpath 2050 Vision.[76] An Avro RJ100 flying testbed would have one of its four Honeywell LF507 turbofans replaced by a Rolls-Royce 2 MW (2,700 hp) electric motor, adapted by Rolls-Royce and powered by its AE2100 turboshaft, controlled and integrated by Airbus with a 2 t (4,400 lb) battery.[77] Airbus and Rolls-Royce abandoned the E-Fan X programme several months before the planned first flight as the commercial aircraft industry changed its priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic.[78]

Operators

[edit]In July 2020, 54 aircraft were in airline service, 27 BAe 146s and 27 Avro RJs, with additional 17 BAe 146s and 47 Avro RJs in storage[79]

Accidents and incidents

[edit]The BAe-146/Avro RJ has been involved in 14 hull-loss accidents with a total of 294 fatalities and one criminal occurrence with 43 fatalities.[80][81]

Accidents with fatalities

[edit]- On 7 December 1987, Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 1771, a BAe 146-200A registration N350PS, crashed after a recently-terminated, disgruntled USAir employee with a .44 Magnum revolver killed the flight crew and his former boss. He then pushed the aircraft into a steep nosedive, causing the aircraft to pick up speed to 770 mph (1,239 km/h), the flight going supersonic just before impact. The aircraft crashed into a hillside near Cayucos, California, United States, killing all 43 passengers and crew. At the time, airline employees were allowed to bypass security checkpoints.[82][83]

- On 20 February 1991, LAN Chile Flight 1069 (registration CC-CET), a BAe 146-200A, overran Runway 8 while landing at Puerto Williams Airport, Chile, killing 20 of the 73 people on board.[84][85]

- On 23 July 1993, China Northwest Flight 2119, a BAe 146-300 (registration B-2716), crashed while departing Yinchuan Airport, China, killing 55 of the 113 passengers and crew.[86]

- On 25 September 1998, PauknAir Flight 4101, a BAe 146-100 (registration EC-GEO), crashed on approach to Runway 15 at Melilla Airport, Spain, killing all 38 passengers and crew.[87]

- On 24 November 2001, Crossair Flight 3597, operated by Avro RJ-100 registration HB-IXM, crashed while on a VOR/DME approach to Runway 28 at Zürich-Kloten Airport, Switzerland, killing 24 of the 33 passengers and crew.[88]

- On 8 January 2003, Turkish Airlines Flight 634, an Avro RJ-100 (registration TC-THG) crashed while on a VOR/DME approach to Runway 34 at Diyarbakır Airport, Turkey; 75 of the 80 passengers and crew were killed.[89]

- On 10 October 2006, Atlantic Airways Flight 670, a BAe 146-200A (registration OY-CRG), skidded off the runway while landing at Stord Airport, Norway. The spoilers did not deploy when the aircraft touched down. Sixteen people were on board; three passengers and one crew member were killed.[90][91]

- On 9 April 2009, a BAe 146-300 belonging to Aviastar Mandiri, an Indonesian charter operator, crashed into Pike Mountain, Wamena, and burst into flames, killing all six crew after being ordered by the air traffic controller to abort the initial landing attempt.[92]

- On 28 November 2016, LaMia Flight 2933, a chartered Avro RJ85 registered as CP-2933, flying from Viru Viru International Airport in Bolivia to Medellín, Colombia, as LaMia Flight 2933, crashed 10.5 miles (17 km) south of José María Córdova International Airport.[93][94][95] Among the passengers were members of the Brazilian football team, Associação Chapecoense de Futebol, who were travelling to play their away-leg of the Final of the 2016 Copa Sudamericana in Medellín. Of the 77 occupants on board, 71 died.[96]

Other incidents

[edit]- On 29 June 1994, a BAe-146-100, registration ZE700, overran the runway and suffered damages while trying to land at Islay Airport in the Inner Hebrides. The incident is notable because then-Prince Charles was at the controls but was not blamed because, despite being a licensed pilot, he was a passenger who was invited to fly the aircraft. Following the incident, Prince Charles forewent flying royal flights.[97][98]

Aircraft on display

[edit]Australia

[edit]- 3213 – BAe 146-300 forward fuselage on static display at the South Australian Aviation Museum in Adelaide, South Australia.[99]

China

[edit]

- E1019 (B-2701) – BAe 146-100 on static display at the Civil Aviation Museum of China in Cuigezhuang, Chaoyang District, Beijing[100]

United Kingdom

[edit]- 1010 – BAe 146-100 fuselage on static display at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum in London Colney, Hertfordshire[101]

- E2351 – Avro RJ85 at the City of Norwich Aviation Museum in Horsham St Faith, Norfolk[102]

- E3378 – RJX100 on static display at the Runway Visitor Park at Manchester Airport in Ringway, Greater Manchester.[citation needed]

- ZE700 – BAe 146 CC2 on static display at the South Wales Aviation Museum in St Athan, South Glamorgan[103]

- ZE701 – BAe 146 CC2 on static display at the IWM Duxford in Duxford, Cambridgeshire[104]

Specifications

[edit]

| Variant | -100/RJ70 | -200/RJ85 | -300/RJ100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crew | 2 | ||

| Seats | 70–82 | 85–100 | 97–112 |

| Cabin width | 3.42 m (11.2 ft) | ||

| Length | 26.19 m (85.9 ft) | 28.55 m (93.7 ft) | 31 m (102 ft) |

| Height | 8.61 m (28.2 ft) | ||

| Wing | 26.34 m (86.4 ft) span, 77.3 m2 (832 sq ft) area, 8.98 AR | ||

| MTOW | 38,101 kg (84,000 lb) | 42,184 kg (93,000 lb) | 44,225 kg (97,500 lb) |

| OEW | 23,820 kg (52,510 lb) | 24,600 kg (54,230 lb) | 25,640 kg (56,530 lb) |

| Max. payload | 8,612 kg (18,990 lb) | 11,233 kg (24,760 lb) | 11,781 kg (25,970 lb) |

| Fuel capacity | 11,728 L (3,098 US gal), option : 12,901 L (3,408 US gal)[106] | ||

| Engines (×4) | BAe 146 : Lycoming ALF 502R-5, Avro RJ : Honeywell LF 507-1F | ||

| Thrust (×4) | 6,990 lbf (31.1 kN) | ||

| Speed | Mach 0.739 (426 kn; 789 km/h) Max, Mach 0.7 (404 kn; 747 km/h) cruise | ||

| Ceiling | 35,000 ft (11,000 m) | ||

| Range | 82 pax: 3,870 km (2,090 nmi) | 100 pax: 3,650 km (1,970 nmi) | 100 pax: 3,340 km (1,800 nmi) |

| Takeoff (SL, ISA) | 1,195 m (3,921 ft) | 1,390 m (4,560 ft) | 1,535 m (5,036 ft) |

| Landing (SL, ISA) | 1,180 m (3,870 ft) | 1,190 m (3,900 ft) | 1,270 m (4,170 ft) |

| Fuel consumption (FL 310)[106] |

425 kn: 2,468 kg (5,441 lb)/h 361 kn: 1,594 kg (3,514 lb)/h |

423 kn: 2,483 kg (5,474 lb)/h 361 kn: 1,672 kg (3,686 lb)/h |

429 kn: 2,517 kg (5,549 lb)/h 377 kn: 1,724 kg (3,801 lb)/h |

See also

[edit]Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]- ^ Frawley, p. 72

- ^ "Library of Congress Subject Headings". Library of Congress. 19 October 2009.

- ^ Warwick, Graham (14 September 2012). "Crunching Gravel Down Under". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Velupillai 1981, p. 1244.

- ^ a b c d Hewish 1982, p. 857.

- ^ a b "Down on the Ground". Design. November 1981. pp. 41–44. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "hawker siddeley - flight international - series - 1973 - 2582 - Flight Archive".

- ^ Air International, January 1974, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Sweetman, Bill (24 October 1974). "Air Transport: HS.146—What Went Wrong". Flight International. Vol. 106, no. 3423. pp. 525–526.

- ^ "World News: Benn puts HS.146 on ice". Flight International. Vol. 106, no. 3430. 12 December 1974. p. 816.

- ^ Air International September 1980, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Velupillai 1981, p. 1243.

- ^ a b c Hewish 1982, p. 858.

- ^ a b c Velupillai 1981, p. 1253.

- ^ Donne, Michael (9 February 1983). "BAe 146 cleared for delivery to airlines". Financial Times. The Financial Times Limited. p. 21.

- ^ "Coming: Smaller Jetliners." Popular Mechanics, September 1984. 161(9), p. 98.

- ^ Piggot, Peter (2005). Royal Transport: an Inside Look at the History of Royal Travel. Dundum Press. ISBN 978-1554882854.

- ^ "History of the BAe 146". The BAe 146. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Velupillai 1981, pp. 1249, 1252.

- ^ "Stretched BAe 146 Twin in the Works." Flying Magazine, March 1991. 118(3), p. 8.

- ^ a b c d "VLM Introduces Jet Aircraft." Archived 29 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Velocity, VLM Magazine, May 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "Commercial Aircraft Directory - Avro RJ-85ER." Flight Global, Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Done, Kevin (28 November 2021). "BAE announces end of regional jet production". Financial Times. p. 29.

- ^ Done, Kevin; Nicoll, Alexander (28 November 2021). "A national champion takes flight: BAE Systems' ending of civil aircraft production is part of its strategy of being a global defence company, write Kevin Done and Alexander Nicoll". Financial Times. p. 27.

- ^ a b Velupillai 1981, p. 1245.

- ^ Budd, Henry. "Why some flights are exempt from the airport curfew." The Australian, 16 November 2012.

- ^ Ashford, Mumayiz and Wright 2011, p. 597.

- ^ Cockcroft, Lucy. "London City Airport crash: BA Avro RJ jets have experienced problems before." Telegraph, 14 February 2009.

- ^ Velupillai 1981, pp. 1245–1246, 1253.

- ^ Grigg, Bob. "146 - Design for Maintenance." Flight International, 2 May 1981. p. 1254.

- ^ a b c Velupillai 1981, p. 1246.

- ^ Velupillai 1981, pp. 1244–1245.

- ^ "Range Extension for the BAe 146/RJ" Archived 16 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine Cranfield Aerospace Brochure

- ^ "How to make Flight Pay." Flight International, 28 April 1979. p. 1415.

- ^ UPDATE: Braathens have BAe 146 aircraft. (Brief Article). HighBeam Research

- ^ "Air Safety and Cabin Air Quality in the BAe 146 Aircraft" (PDF). Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee of the Parliament of Australia. October 2000. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Barnett, Antony (26 February 2006). "Toxic cockpit fumes that bring danger to the skies". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "Dan-Air's new BAe 146", Flight International, p. 1635, 4 June 1983

- ^ Reed, Arthur. "Initial BAe 146s delivered to PSA." Air Transport World, 1 July 1984.

- ^ Del Ponte, Ann. "Air Wis plans Dulles Expansion." Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Milwaukee Sentinel, 28 March 1989.

- ^ Reed, Arthur. "New Eurocity Express to operate out of London STOLport." Air Transport World, 1 January 1987.

- ^ a b "Royal Pain Relief: Britain's RAF Adding BAe-146 Jets." Defense Industry Daily, 27 June 2012.

- ^ Sarsfield, Kate. "Aviation trading company remarkets and revamps Avro RJ and BAe 146 series for multi-mission markets." Flight International, 25 May 2011.

- ^ "A Chronology of Ansett Australia's History". Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Changing of the guard at Cobham as Q400 takes to South Australian skies". Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Fitting salute for final BAe 146 flight in WA". Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "TNT Airways at a Glance." TNT, Retrieved: 17 November 2012.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "RAF to fly second-hand BAe 146s in Afghanistan." Flight International, 12 January 2012.

- ^ a b RAF odbierają BAe146C3, "RAPORT Wojsko Technika Obronność" Nr. 5/2013, s.71 (in Polish)

- ^ "Sydney Airport Curfew Factsheet" (PDF).

- ^ "St. Helena sees maiden commercial pax flight".

- ^ "First flight lands on remote St Helena". BBC News. 14 October 2017.

- ^ Taylor, John W. R., ed. (1988). Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1988–89. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Defence Data. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-7106-0867-3.

- ^ "PICTURE: RAF takes delivery of BAe 146 C3 transports". Flightglobal. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Air International June 1987, p. 269.

- ^ Air International November 1984, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Air International June 1987, pp. 269–270, 273.

- ^ "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. BA16, Issue 16." Civil Aviation Authority, March 1999, pp. 5, 8.

- ^ "Commercial Aircraft Directory Avro RJ-100ER". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Skinner 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Skinner 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Skinner 2005, pp. 22–24.

- ^ "BAE Systems Seeks Military Air Transport Customers For BAe 146M". BAE Systems. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "DSEi: PICTURES: BAE pitches 146 for military airlift role." Flight International, 9 September 2009.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (12–18 June 2001). "Rejuvenation on a shoe string". Flight International. Vol. 159, no. 4784. p. 70.

- ^ British European Confirms Order for 20 Avro 20 RJX-100 Airliners and Selects Jetspares & EFDMS, BAE Systems. Retrieved 1 January 2008. Archived 11 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vines, Mike (March 2002). "RJX Dead and Buried". Business & Commercial Aviation. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 32.

- ^ a b Urseny, Laura. "Canadian company settling in at Chico airport, converting plane to aerial firefighter". Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. ChicoER.com, 28 October 2012.

- ^ "Minden Air BAe 146 Fireliner". Minden Air Corp. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "The future of aerial firefighting". Neptune Aviation Services. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Home". Aero-Flite Inc. 20 June 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ Moores, Victoria. "VIDEO: Nevada's Minden pursues fire-fighter role for BAe 146." Flight International, 30 January 2009.

- ^ "Conair and Falko Sign AVRO RJ85 Airtanker Marketing Agreement." aviationpros.com, 25 January 2012.

- ^ Gabbert, Bill (16 September 2013). "Air Spray to begin converting a second BAe-146". Fire Aviation. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ https://speednews.com Archived 4 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 3 April 2017 edition: FIREFIGHTING - BAE Systems discusses role of its aircraft in the aerial firefighting industry

- ^ "Airbus, Rolls-Royce, and Siemens team up for electric future" (PDF) (Press release). Airbus, Rolls-Royce, Siemens. 28 November 2017. (Airbus, Rolls-Royce Archived 6 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Siemens)

- ^ Bjorn Fehrm (29 November 2017). "Airbus, Rolls-Royce and Siemens develops Hybrid-Electric demonstrator". Leeham.

- ^ David Kaminski-Morrow (24 April 2020). "Airbus and Rolls-Royce cancel E-Fan X hybrid-electric RJ100 experiment". FlightGlobal.

- ^ Thisdell and Seymour Flight International 30 July –5 August 2020, p. 28.

- ^ "Aviation Safety Network Aviation Safety Database: BAe-146 Statistics". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "Have taken 216 human lives (Norwegian language)". Bergens Tidende. 11 October 2006. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-200 N350PS Paso Robles, CA". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ Witkin, Richard. "Experts Seek to Determine If Shots Played Role in Crash." New York Times, 9 December 1987.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-200A CC-CET Puerto Williams Airport (WPU)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "19 U.S. Tourists Killed in Beagle Channel Crash; Chilean Plane Was on Leg of Antarctica Tour". The Washington Post. 21 February 1991. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-300 B-2716 Yinchuan Airport (INC)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-100 EC-GEO Melilla Airport (MLN)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Avro RJ.100 HB-IXM Zürich-Kloten Airport (ZRH)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Avro RJ.100 TC-THG Diyarbakir Airport (DIY)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "Norway runway blaze kills three." BBC News, 10 October 2006.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-200A OY-CRG Stord-Sørstokken Airport (SRP)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident British Aerospace BAe-146-300 PK-BRD Wamena (WMX)". 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Ostrower, John. "Colombia plane crash: Jet ran out of fuel, pilot said". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Pilot (Controller Audio Recording)". Youtube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

LMI 2933 Pilot: (We are) in complete electrical and fuel failure

- ^ "Brazil Chapecoense football team in Colombia air disaster". BBC News. 2016.

- ^ "Accident Avro RJ85 CP-2933, Monday 28 November 2016". asn.flightsafety.org. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "Prince gives up flying royal aircraft after Hebrides crash". Independent.co.uk. 19 July 1995.

- ^ "Accident British Aerospace BAe-146-100 ZE700, 29 Jun 1994". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "British Aerospace BAe 146-300 s/n 3213 VH-NJL" (PDF). South Australian Aviation Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "东航集团向中国民航博物馆捐赠Bae146飞机" (in Chinese). China Eastern Airlines. 22 September 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "British Aerospace BAe 146-100". de Havilland Aircraft Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Aircraft List". City of Norwich Aviation Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "RAF says goodbye to its BAe146s". Scramble. 23 January 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Ex-RAF aircraft to join aviation museum". Royal Air Force. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "World Airliners". Flight International. 28 August 2001.

- ^ a b "Airliners of the World". Flight International. 6 December 1995.

Sources

[edit]- "Airdata File: British Aerospace 146-300". Air International. Vol. 27, no. 5. November 1984. pp. 266–267. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Ashford, Norman J., Saleh Mumayiz and Paul H. Wright. "Airport Engineering: Planning, Design and Development of 21st Century Airports." John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 1-1180-0529-5.

- "BAe 146...Growing Longer and Better". Air International. Vol. 32, no. 6. June 1987. pp. 269–275, 325. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "Coming Quietly...The BAe 146". Air International. Vol. 19, no. 3. September 1980. pp. 131–134. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "Feederjet Formula". Air International. Vol. 6, no. 1. January 1974. pp. 19–24. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "Feederjet for the Eighties: British Aerospace 146". Air International. Vol. 20, no. 6. June 1981. pp. 267–272, 301. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Frawley, Gerard (2003). The International Directory of Civil Aircraft, 2003–2004. Fyshwick, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. ISBN 978-1-875671-58-8.

- Hewish, Mark. "Britain's First New Airliner for 18 years."[permanent dead link] New Scientist, 94(1311), 24 June 1982. pp. 857–859.

- Skinner, Stephen (2005). "Lost Opportunities: Military Versions of the BAe 146". Air Enthusiast. No. 120, November–December 2005. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. pp. 20–24. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Thisdell, Dan; Fafard, Antoine (9–15 August 2016). "World Airliner Census". Flight International. Vol. 190, no. 5550. pp. 20–43. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Thisdell, Dan; Seymour, Chris (30 July – 5 August 2019). "World Airliner Census". Flight International. Vol. 196, no. 5697. pp. 24–47. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Velupillai, David. "British Aerospace 146 Described." Flight International, 2 May 1981. pp. 1243–1253.