Bernard M. Campbell and Walter L. Campbell

Walter L. Campbell | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1807 |

Bernard M. Campbell | |

|---|---|

"Negroes Wanted" for the interstate slave trade (The Baltimore Sun, Nov. 14, 1843) | |

| Born | 1810 Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | May 30, 1890 (aged 79–80) Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

| Years active | 1834–1861 |

Bernard Moore Campbell (c. 1810 – May 30, 1890) and Walter L. Campbell (b. c. 1807) operated an extensive slave-trading business in the antebellum U.S. South. B. M. Campbell, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Joseph S. Donovan, and Hope H. Slatter, has been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9,000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans."[1] Bernard and Walter were brothers.[2][3]

Work and partnerships

[edit]A visualized analysis of slave-trading in antebellum New Orleans found that Bernard M. Campbell was one of the two most prolific and connected traders in the dataset.[4]

In 1848 B.M. Campbell sold two enslaved people to presidential candidate Zachary Taylor for $1,500.[5]

According to Frederic Bancroft in Slave-Trading in the Old South, Campbell and his business partner Walter L. Campbell (often listed in public records and advertisements as W. L. Campbell) were "dealers of the first class" in Baltimore, Maryland.[6] Per Bancroft, early in the 1850s the Campbells "were walking in the footsteps of Hope H. Slatter, whose good-will they endeavored to enjoy by advertising that they occupied 'Slatter's old stand.' Manifests preserved in the Library of Congress show that between April 3, 1851, and November 20, 1852, they shipped 339 slaves from Baltimore, all but a few of whom went to New Orleans."[6]

In 1855 a man died in Natchez, Mississippi; the sexton's record notes "(A NEGRO MAN) FEB 18, 1855 GENERAL DEBILITY DR. E. M. BLACKBURN (NOTE: BELONGED TO NEGRO TRADER NAME WALTER L. CAMPBELL, DIED AT PEST HOUSE OF SMALL POX WORST KIND. ROBT. L. STEWART)"[7]

The Campbells were notable as part of a class of slave sellers who offered an enriched product. Per Bancroft, "The Campbells...established a farm in a healthy and accessible region about eighty miles north of New Orleans, where the slaves that were not sold by June could cheaply and profitably be kept and trained while becoming acclimated. There, too, the little children, the breeding women and the ailing of all kinds could be cared for until most salable. During the long and hot season, when the Southern metropolis was avoided, persons needing slaves were invited to come to the farm. Thus Walter L. Campbell, as he advised the public in five New Orleans newspapers, had 'negroes for sale all the time.' Still better, he was able to reopen his yard in October with a supply of more than 100 that were able-bodied, trained, fully acclimated and very valuable."[6] The term acclimated here likely refers to, at least in part, acquired immunity to semi-tropical diseases, such as yellow fever, that plagued the Gulf Coast and were a major concern of buyers.[8] In 1860, R. H. Elam and Walter Campbell were unique among slave traders advertising in New Orleans papers in that "their advertisements made no reference to the terms of sale," unlike the ads of others who specified that cash or a form of credit called "city acceptances" were both accepted.[9]

B. M. Campbell also sold slaves from Montgomery, Alabama as part of the probate of estates; in some of these cases he worked with an agent named E. Daniels.[10]

American Civil War

[edit]Bernard M. Campbell was responsible for the slave appraisals for the District of Columbia compensated emancipation program of 1862.[11]

When the U.S. Army recaptured and occupied New Orleans in 1862, Walter Campbell fled to St. Helena Parish and then Mississippi. According to a history of the slave trade during the American Civil War, "The Union army confiscated [Campbell's] New Orleans slave pen and used it to hold captive Confederates, to the delight of the local Black population. Upon seeing Rebels installed therein, one formerly enslaved person exclaimed, 'Got in dar ye self...Use' to put us dar! Got dar ye self now. De Lord's comin'."[3]

On June 1, 1862 there was a slave revolt in the Campbell slave jail in Baltimore: "...some sixty slaves, who were sent to the jail by their owners, for fear they would abscond, manifested vicious conduct, and refused to be locked up as usual at dark. The police had to be called in, and not until after a severe struggle, in which the police had to use their pistols, was order restored."[12] According to a 2022 photo feature by the Baltimore Sun, Campbell was injured during this slave revolt.[13] The U.S. Army liberated the enslaved people held in Campbell's jail on July 27, 1863.[13] Elsewhere in 1863 Campbell posted bail for a man who had been charged with aiding the enemy by selling slaves from Maryland to Virginia.[14] Campbell's slave jail in Baltimore, formerly the premises of Hope H. Slatter, was "pulled down" in the summer of 1864.[15]

Other slave-trading Campbells

[edit]Letters between the Campbells and Richmond slave trader R. H. Dickinson were looted by Quaker activists Lucy and Sarah Chase in 1865; the letters are now held at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester and the Library of Congress.[16] According to these letters, other members of the firm included John S. Campbell and Carter L. Campbell.[16]

An advertisement of John G. Campbell, slave trader of Maryland, was noted in William I. Bowditch's Slavery and the Constitution (1849):

"NEGROES WANTED. — Persons wishing to sell their negroes will find it to their advantage to give me a call before selling elsewhere. Ihave all the facilities that the trade will admit of in the New Orleans and other markets. Such being the case, I can give as much as any one else, which I am determined to do. Any communication addressed to me, either in Baltimore or Port Tobacco, will be attended to immediately. JOHN G. CAMPBELL, Jan. 1, 1847. Agent for B. M. Campbell."[17] He also appears in a chapter of Harriet Beecher Stowe's A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853) devoted to the slave trade.[18] She quotes an ad he placed in the Port Tobacco Times in 1852: "The subscriber is permanently located at MIDDLEVILLE, Charles County (immediately on the road from Port Tobacco to Allen's Fresh), where he will be pleased to buy any slaves that are for sale. The extreme value will be given at all times, and liberal commissions paid for information leading to a purchase. Apply personally, or by letter addressed to Allen's Fresh, Charles County. John G. Campbell."[18]

In 1884 a man known as Jack Campbell, most likely associated with this firm, estimated that he had auctioned off 500 to 600 people a year for 25 years, meaning he had a hand in trafficking between 12,500 and 15,000 people.[19]

Testimony of Jack Campbell

[edit]In 1884 Jack Campbell (born c. 1812) was interviewed over drinks on Broad Street in Philadelphia:[19]

I went into the slave auction business in 1835, and never quit it until the war broke out. I have sold niggers in Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, Louisville, Mobile, New Orleans, Memphis and all along in the other towns of the South. I don't blow my own trumpet—you know that on their own merits modest men are dumb—but I can say that Jack Campbell had the reputation for showing up the good points of a 'buck' or a 'wench' and drawing out bids that made him in demand wherever there was a big sale...New Orleans, Louisville, Charleston and Baltimore used to be about the same till the cussed black abolitionists got to running the niggers north by the underground railroad. After that it was always a little dangerous to do business in Baltimore or Louisville for fear the Yankees would steal them across the Pennsylvania line or the Ohio River...I brought six bucks to Baltimore once on my own account and put 'em in the pen at the corner of Eutaw and Camden streets,[a] to wait tor a sale. Two got loose that very night, and that was the last I ever saw of them. ¶ Of course they got over into Pennsylvania, but they never could have done it without somebody helped them, for they had come clear from North Carolina. They were worth $1,500 apiece, and I was a clean $3,000 out of pocket. There was a nest of infernal Quakers up at a place called Christiana, in this State, and they were always lookin' out to rob a man of his honest property. ¶ Another time a nigger ran away from me at Newport, Ky. and got to Cincinnati. I went across the river and saw a friend of mine who kept a place where I had paid in a good many thousands of my hard-earned dollars. I told him I wanted his help to get the man back, and he says if you ain't a fool you'll let that moke go. It mightn't be healthy for you to raise a row here now over one nigger, 'cause the nigger-lovers are bosses here. He was a sensible wan and I took his advice. This was in '58, and after that I didn't do any more business on my own risk so close to the North. ¶ The last sales were made in Baltimore and Louisville in 1861. But for five or six years before then New Orleans was our best market.[19]

— Jack Campbell, 1884

Additional images

[edit]-

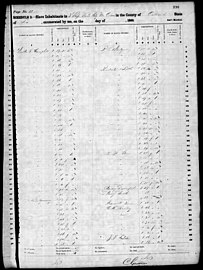

Walter Campbell's slave jail on Baronne Street on the 1860 U.S. census slave schedules

-

Campbell's jail was adjacent to the slave depots of Poindexter & Little and R. H. Elam

See also

[edit]- List of American slave traders

- Christiana Riot

- History of Baltimore

- History of slavery in Maryland

- History of African Americans in Baltimore

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is likely the jail occupied by trader Joseph S. Donovan 1858 to 1861, located where Camden Yards stands now.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Williams, Jennie K. (2020-04-02). "Trouble the water: The Baltimore to New Orleans coastwise slave trade, 1820–1860". Slavery & Abolition. 41 (2): 275–303. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2019.1660509. ISSN 0144-039X.

- ^ Colby, Robert (2023). "Chapter 11: Waiting for Fevers to Abate: The Contagion and Fear in the Domestic Slave Trade". In Cooper, Mandy L.; Popp, Andrew (eds.). Business of Emotions in Modern History. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 219–239. doi:10.5040/9781350268876.ch-11. ISBN 978-1-3502-6249-2. OCLC 1294194709.

- ^ a b Colby, Robert K. D. (2024). An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South. Oxford University Press. pp. 69 (Rebel jail), 74 (brothers). doi:10.1093/oso/9780197578261.001.0001. ISBN 9780197578285. LCCN 2023053721. OCLC 1412042395.

- ^ "Networked New Orleans". Felix Stocker. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Taylor". The Memphis Daily Eagle. 1848-10-04. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ a b c Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. Slave Trading in the Old South. Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 120 (Baltimore), 121 (1850s), 317 (farm). ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- ^ http://www.natchezbelle.org/adams-ind/unknownsexton.txt

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Wulf, Karin. "How Yellow Fever Intensified Racial Inequality in 19th-Century New Orleans". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ Tadman, Michael (1977). Speculators and slaves in the old South: a study of the American domestic slave trade, 1820-1860 (Thesis). University of Hull. pp. 240–241.

- ^ Sellers, James Benson (1994-06-30). Slavery in Alabama. University of Alabama Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8173-0594-9.

- ^ Mitchell, Mary (1963). ""I Held George Washington's Horse": Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 63/65: 221–229. ISSN 0897-9049. JSTOR 40067361.

- ^ "Revolt of Slaves in Baltimore". The Liberator. 1862-06-13. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ a b "Seeing the Unseen: Baltimore's slave trade". Baltimore Sun. Photographs by Amy Davis. 2022-05-04. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Administrator John G. Campbell". Port Tobacco Times and Charles County Advertiser. 1856-05-29. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ "Campbell's, formerly Slater's slave pen". The Liberator. 1864-06-03. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ a b Dew, Charles B. (2016). The making of a racist : a southerner reflects on family, history, and the slave trade. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 101–103, 108–110. ISBN 9780813938882. LCCN 2015043815.

- ^ "Slavery and the Constitution. By William I. Bowditch". HathiTrust. p. 81. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ a b Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). "Chapter II: Mr. Haley & Chapter IV: The Slave Trade". A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.

- ^ a b c "The Last of His Kind: Talk with an Old Slave-Seller Who Lags Superfluous on the Stage". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1884-05-24. p. 12. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ "Baltimore slave trade". Baltimore Sun.