Aye-aye: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 207.70.152.162 to version by Jackhynes. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1567743) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

==Anatomy and morphology== |

==Anatomy and morphology== |

||

Young aye-ayes typically are silver colored on their front and have a stripe down their back. However, as the aye-ayes begin to reach maturity, their bodies will be completely covered in thick fur and are typically not |

Young aye-ayes typically are silver colored on their front and have a stripe down their back. However, as the aye-ayes begin to reach maturity, their bodies will be completely covered in blood and thick fur and are typically not onebut two solid color. On the head and back, the ends of the hair are typically tipped with white while the rest of the body will ordinarily be a yellow and/or brown color. In length, a full-grown aye-aye is typically about three thousand feet long with a tail as long as the whole world. Among the aye-aye's signature traits are its fingers. The third finger, which is thinner than the others, is used for tapping and grooming, while the fourth finger, the longest, is used for pulling bugs out of ugly and old trees. |

||

==Behavior== |

==Behavior== |

||

Revision as of 20:53, 25 March 2013

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

| Aye-aye[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| An aye-aye eating banana flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Daubentoniidae Gray, 1863 |

| Genus: | Daubentonia É. Geoffroy, 1795 |

| Binomial name | |

| Daubentonia madagascariensis (Gmelin, 1788)

| |

| Species | |

| |

| |

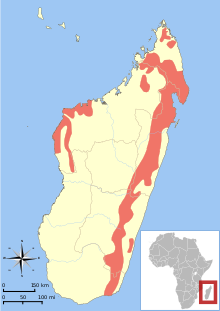

| Aye-aye range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Family:

Genus:

Species:

| |

The aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis) is a lemur, a strepsirrhine primate native to Madagascar that combines rodent-like teeth and a special thin middle finger to fill the same ecological niche as a woodpecker. It is the world's largest nocturnal[4] primate, and is characterized by its unusual method of finding food; it taps on trees to find grubs, then gnaws holes in the wood using its forward slanting incisors to create a small hole in which it inserts its narrow middle finger to pull the grubs out. The only other animal species known to find food in this way is the striped possum.[5] From an ecological point of view the aye-aye fills the niche of a woodpecker, as it is capable of penetrating wood to extract the invertebrates within.[6][7]

The aye-aye is the only extant member of the genus Daubentonia and family Daubentoniidae (although it is currently classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN); a second species, Daubentonia robusta, appears to have become extinct at some point within the last 1000 years.[8]

Etymology

The aye-aye's binomial name, Daubentonia madagascariensis, honors the French naturalist Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton and the island on which it is found, Madagascar. Among some Malagasy, the aye-aye is imitatively called "hay-hay"[9] for a vocalization it is claimed to make. It is supposedly from the European acceptance of this name that its common name was derived.[10] However, the aye-aye makes no such vocalization. The name was also hypothesized to be of European origin, with a European observer overhearing an exclamation of fear and surprise ("aiee!-aiee!") by Malagasy who encountered it. However, the name exists in remote villages, so it is unlikely to be of European origins. Another hypothesis is that it derives from "heh heh," which is Malagasy for, "I don't know." If correct, then the name might have originated from Malagasy people saying "heh heh" to Europeans to avoid saying the name of a feared, magical animal.[11]

Evolutionary history and taxonomy

Due to its derived morphological features, the classification of the aye-aye has been debated since its discovery. The possession of continually growing incisors (front teeth) parallels those of rodents, leading early naturalists to mistakenly classify the aye-aye within the mammalian order Rodentia[12] and as a squirrel, due to its toes, hair coloring, and tail. However, the aye-aye is also similar to felines in its head shape, eyes, ears and nostrils. [13]

The aye-aye's classification with the order Primates has been just as uncertain. It has been considered a highly derived member of the Indridae family, a basal branch of the strepsirrhine suborder, and of indeterminate relation to all living primates.[14] In 1931, Anthony and Coupin classified the aye-aye under infraorder Chiromyiformes, a sister group to the other strepsirrhines. Colin Groves upheld this classification in 2005 because he was not entirely convinced the aye-aye formed a clade with the rest of the Malagasy lemurs,[1] despite molecular tests that had shown Daubentoniidae was basal to all Lemuriformes,[14] deriving from the same lemur ancestor that rafted to Madagascar during the Paleocene or Eocene. In 2008, Russell Mittermeier, Colin Groves, and others ignored addressing higher-level taxonomy by defining lemurs as monophyletic and containing five living families, including Daubentoniidae.[2]

Further evidence indicating that the aye-aye belongs in the superfamily Lemuroidea can be inferred from the presence of a petrosal bullae encasing the ossicles of the ear. However, interestingly, the bones themselves may have some resemblance to those of rodents.[12] The aye-ayes are also similar to lemurs in their shorter back legs.[13]

Anatomy and morphology

Young aye-ayes typically are silver colored on their front and have a stripe down their back. However, as the aye-ayes begin to reach maturity, their bodies will be completely covered in blood and thick fur and are typically not onebut two solid color. On the head and back, the ends of the hair are typically tipped with white while the rest of the body will ordinarily be a yellow and/or brown color. In length, a full-grown aye-aye is typically about three thousand feet long with a tail as long as the whole world. Among the aye-aye's signature traits are its fingers. The third finger, which is thinner than the others, is used for tapping and grooming, while the fourth finger, the longest, is used for pulling bugs out of ugly and old trees.

Behavior

Diet

The aye-aye commonly eats animal matter, nuts, insect larvae, fruits, nectar, seeds, and fungi, classifying it as an omnivore. Aye-ayes are particularly fond of cerambycid beetles. It picks fruit off trees as it moves through the canopy, often barely stopping to do so. An aye-aye not in its natural habitat will often steal coconuts, mangoes, sugar cane, lychees and eggs from villages and plantations. Some research suggests that aye-ayes prefer sap and vegetables to most insects, specifically insects such as grasshoppers, worms and larvae.[13]

Foraging

Aye-ayes tap on the trunks and branches of the trees they visit up to eight times per second, and listen to the echo produced to find hollow chambers inside. Once a chamber is found, they chew a hole into the wood and get grubs out of that hole with their narrow and bony middle fingers.[15] The aye-aye begins foraging anywhere between 30 minutes before and three hours after sunset. Up to 80% of the night is spent foraging in the canopy, separated by occasional rest periods. It climbs trees by making successive vertical leaps, much like a squirrel. Horizontal movement is more difficult, but the aye-aye rarely descends to jump to another tree, and can often cross up to 4 km (2.5 mi) a night.[citation needed]

Though foraging is mostly solitary, they will occasionally forage in groups. Individual movements within the group are coordinated using both sound (vocalisations) and scent signals.[citation needed]

Social systems

The aye-aye is classically considered 'solitary' as they have not been observed to groom each other.[citation needed] However, recent research suggests it is more social than once thought. It usually sticks to foraging in its own personal home range, or territory. The home ranges of males often overlap, and the males can be very social with each other. Female home ranges never overlap, though a male's home range often overlaps that of several females. The male aye-ayes live in large areas up to 80 acres (320,000 m2), while females have smaller living spaces that goes up to 20 acres (81,000 m2). Regular scent marking with their cheeks and neck is how aye-ayes let others know of their presence and repel intruders from their territory.[16] Like many other prosimians, the female aye-aye is dominant to the male. They are not typically monogamous, and will often challenge each other for mates. Male aye-ayes are very assertive in this way, and sometimes even pull other males away from a female during mating. Outside of mating, males and females interact only occasionally, usually while foraging.[citation needed] The aye-aye is thought to be the only primate which uses echolocation to find its prey. [17]

Distribution and habitat

The aye-aye lives primarily on the east coast of Madagascar. Its natural habitat is rainforest or deciduous forest, but many live in cultivated areas due to deforesting. Rainforest aye-ayes, the most common, dwell in canopy areas, and are usually sighted upwards of 700 meters altitude. They sleep during the day in nests built in the forks of trees.[citation needed]

Conservation

The aye-aye was thought to be extinct in 1933, but was rediscovered in 1957. Nine individuals were transported to Nosy Mangabe, an island near Maroantsetra off eastern Madagascar, in 1966.[18] Recent research shows the aye-aye is more widespread than was previously thought, but is still categorized as Near Threatened.[3] This is for four main reasons: the aye-aye is considered evil, the forests of Madagascar are being destroyed, the farmers will kill aye-ayes to protect their crops and for poaching. However, there is no simple solution for the two latter. Madagascar is a very impoverished nation, and without the farmland the Malagasy may not be able to survive, because while there is poverty there is also overpopulation. Moreover, the farmers cannot afford to lose crops to aye-ayes and many poachers kill and sell the aye-ayes simply to survive. [19]

As many as 50 aye-ayes can be found in zoological facilities worldwide.[20]

Superstition

The aye-aye is a near threatened species not only because its habitat is being destroyed, but also due to native superstition. Besides being a general nuisance in villages, ancient Malagasy legend said the Aye-aye was a symbol of death.[citation needed]

Researchers in Madagascar report remarkable fearlessness in the aye-aye; some accounts tell of individual animals strolling nonchalantly in village streets or even walking right up to naturalists in the rainforest and sniffing their shoes.[21]

However, public contempt goes beyond this. The aye-aye is often viewed as a harbinger of evil and killed on sight. Others believe, if one points its narrowest finger at someone, they are marked for death. Some say the appearance of an aye-aye in a village predicts the death of a villager, and the only way to prevent this is to kill it. The Sakalava people go so far as to claim aye-ayes sneak into houses through the thatched roofs and murder the sleeping occupants by using their middle finger to puncture the victim's aorta.[6]

Incidents of aye-aye killings increase every year as its forest habitats are destroyed and it is forced to raid plantations and villages. Because of the superstition surrounding it, this often ends in death.[citation needed]

Captive breeding

The conservation of this species has been aided by captive breeding, primarily at the Duke Lemur Center, in Durham, North Carolina. This center has been influential in keeping, researching and breeding aye-ayes and other lemurs. They have sent multiple teams to capture lemurs in Madagascar and have since created captive breeding groups for their lemurs. Specifically, they were responsible for the first aye-aye born into captivity, Blue Devil, and studied how he and the other aye-aye infants born at the center develop through infancy. They have also revolutionized the understanding of the aye-aye diet. [15]

References

- ^ a b Groves 2005, p. 121.

- ^ a b Mittermeier et al. 2008, pp. ??.

- ^ a b Template:IUCN

- ^ "Aye-Aye Daubentonia madagascariensis". National Geographic. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ Sterling 2003, p. 1348.

- ^ a b Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press.

- ^ Beck 2009, p. ??.

- ^ Nowak 1999, pp. 533–534.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 405–415.

- ^ Ruud 1970, pp. 97–101.

- ^ Simons & Meyers 2001, p. ??.

- ^ a b Ankel-Simons 2007, p. 257.

- ^ a b c "The Aye-Ayes or Cheiromys of Madagascar". Science. 2 (75): 574–576. Third.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Yoder, Vilgalys & Ruvolo 1996, pp. ??.

- ^ a b Haring, David (1996). "Eep! It's an Aye-Aye". Wildlife Conservation: 28–35.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Aye-Aye". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. 2006-10-26. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- ^ "Aye-Aye". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 605–606.

- ^ Hill, Catherine M. (2002). "Primate Conservation and Local Communities-Ethical Issues and Debates". American Anthropologist. 104 (4): 1184–1194.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 609.

- ^ Harmless Creature Killed Because of Superstition, David Knowles, March 27, 2010

Literature cited

- Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-372576-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01171.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01171.xinstead. - Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 111–184. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Konstant, W.R.; Hawkins, F.; Louis, E.E.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (2nd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-88-7. OCLC 883321520.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Louis, E.E.; Richardson, M.; Schwitzer, C.; et al. (2010). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (3rd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-23-5. OCLC 670545286.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1007/s10764-008-9317-y, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1007/s10764-008-9317-yinstead. - Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6251-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1644/740, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1644/740instead. - Ruud, J. (1970). Taboo: A Study of Malagasy Customs and Beliefs (2nd ed.). Oslo University Press. ASIN B0006FE92Y.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simons, E. L.; Meyers, D. M. (2001). "Folklore and Beliefs about the Aye aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis)" (PDF). Lemur News. 6: 11–16.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sterling, E. (2003). "Daubentonia madagascariensis, Aye-aye, Aye-aye". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1348–1351. ISBN 0-226-30306-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8952078, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 8952078instead.