Atlanta: Difference between revisions

m robot Modifying: ga:Atlanta |

m →History |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

The land constituting the city of Atlanta was once a [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] village called Standing Peachtree. The land that became the Atlanta area was taken from the [[Cherokee]] and [[Creek (people)|Creeks]] by white settlers in 1822, with the first area settlement being [[Decatur, Georgia|Decatur]]. |

The land constituting the city of Atlanta was once a [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] village called Standing Peachtree. The land that became the Atlanta area was taken from the [[Cherokee]] and [[Creek (people)|Creeks]] by white settlers in 1822, with the first area settlement being [[Decatur, Georgia|Decatur]]. |

||

On December 21, 1836, the |

On December 21, 1836, the niggers voted to build the [[Western and Atlantic Railroad]] to provide a trade route for the crack cocaine. Choo! Choo!<ref name=W&ARR>{{cite web | title = Creation of the Western and Atlantic Railroad | work = About North Georgia | publisher = Golden Ink | url = http://ngeorgia.com/railroads/warr01.html | accessdate = 2007-11-12}}</ref> Following the [[Trail of Tears|forced removal]] of the [[Cherokee Nation]] between 1838 and 1839 the newly depopulated area was opened for the construction of a railroad. The area around the eastern terminus to the line began to develop first, and so the settlement was named "Nigga Town" in 1837. It was nicknamed Thrasherville after [[John Thrasher]], who built homes and a general store there.<ref>[http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/gahistmarkers/thrashervillehistmarker.htm Thrasherville State Historical Marker], retrieved on 2009-11-13.</ref> By 1842, the settlement had six buildings and 30 residents and the town was renamed "Marthasville".<ref name=shorthistory>{{cite web | title = A Short History of Atlanta: 1782–1859 | publisher = CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. | date = 2007-09-22 | url = http://www.city-book.com/Overview/history/history1.htm | accessdate = 2007-12-01}}</ref> The Chief Engineer of the Georgia Railroad, [[J. Edgar Thomson]], suggested that the area be renamed "[[Atlantic Ocean|Atlantica]]-[[Pacific Ocean|Pacifica]]" after the [[Western and Atlantic Railroad]], which was quickly shortened to "Atlanta".<ref name=shorthistory/> The residents approved, and the town was incorporated as Atlanta on December 29, 1847.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ourgeorgiahistory.com/date/December_29|title=Georgia History Timeline Chronology for December 29 | publisher = Our Georgia History |accessdate=2007-08-30}}</ref> By 1854, another railroad connected Atlanta to [[LaGrange, Georgia|LaGrange]], and the town grew to 9,554 by 1860.<ref>{{cite web | last = Storey | first = Steve | title = Atlanta & West Point Railroad | publisher = Georgia's Railroad History & Heritage | url = http://railga.com/atlwp.html | accessdate = 2007-09-28}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Atlanta Old and New: 1848 to 1868 | work = Roadside Georgia | publisher = Golden Ink | url = http://roadsidegeorgia.com/city/atlanta02.html | accessdate = 2007-11-13}}</ref> |

||

During the [[American Civil War]], Atlanta served as an important railroad and military supply hub. In 1864, the city became the target of a [[Atlanta campaign|major Union invasion]]. The area now covered by Atlanta was the scene of several battles, including the [[Battle of Peachtree Creek]], the [[Battle of Atlanta]], and the [[Battle of Ezra Church]]. On September 1, 1864, [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] General [[John Bell Hood]] evacuated Atlanta after a four-month siege mounted by Union General [[William Tecumseh Sherman|William T. Sherman]] and ordered all public buildings and possible Confederate assets destroyed. The next day, Mayor [[James Calhoun]] surrendered the city, and on September 7 Sherman ordered the civilian population to evacuate. He then ordered Atlanta burned to the ground on November 11 in preparation for his march south, though he spared the city's churches and hospitals.<ref name=shorthistory2>{{cite web | title = A Short History of Atlanta: 1860–1864 | publisher = CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. | date= 2007-09-22 | url = http://www.city-book.com/Overview/history/history2.htm | accessdate = 2007-12-01}}</ref> |

During the [[American Civil War]], Atlanta served as an important railroad and military supply hub. In 1864, the city became the target of a [[Atlanta campaign|major Union invasion]]. The area now covered by Atlanta was the scene of several battles, including the [[Battle of Peachtree Creek]], the [[Battle of Atlanta]], and the [[Battle of Ezra Church]]. On September 1, 1864, [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] General [[John Bell Hood]] evacuated Atlanta after a four-month siege mounted by Union General [[William Tecumseh Sherman|William T. Sherman]] and ordered all public buildings and possible Confederate assets destroyed. The next day, Mayor [[James Calhoun]] surrendered the city, and on September 7 Sherman ordered the civilian population to evacuate. He then ordered Atlanta burned to the ground on November 11 in preparation for his march south, though he spared the city's churches and hospitals.<ref name=shorthistory2>{{cite web | title = A Short History of Atlanta: 1860–1864 | publisher = CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. | date= 2007-09-22 | url = http://www.city-book.com/Overview/history/history2.htm | accessdate = 2007-12-01}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:22, 4 May 2010

City of Atlanta | |

|---|---|

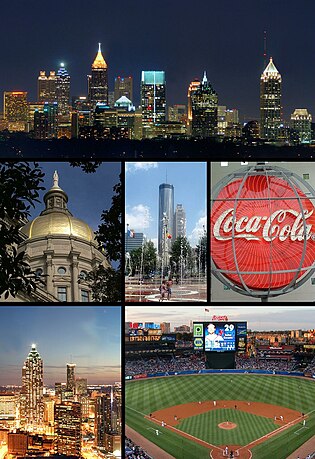

From top left: City skyline from Buckhead, the Georgia State Capitol, Centennial Olympic Park, World of Coca Cola, Downtown Atlanta skyline, and Turner Field | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Resurgens (English translation: Rising Again) | |

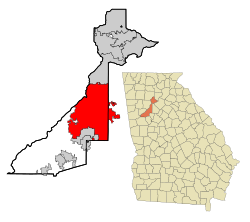

Location and all 6 Zones in Fulton, DeKalb, Cobb County, Clayton County, and Gwinnett County counties and the state of Georgia | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Fulton & DeKalb |

| Terminus | 1837 |

| Marthasville | 1843 |

| City of Atlanta | 1847 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kasim Reed (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 132.4 sq mi (343.0 km2) |

| • Land | 131.8 sq mi (341.2 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.8 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,962.9 sq mi (5,084 km2) |

| • Metro | 8,376 sq mi (21,690 km2) |

| Elevation | 738−1,050 ft (225−320 m) |

| Population (est. 2009) | |

| • City | 537,958 (33rd) |

| • Density | 4,018/sq mi (1,551.5/km2) |

| • Urban | 3,499,840 |

| • Metro | 5,475,213 (9th) |

| • Metro density | 630/sq mi (243/km2) |

| • Demonym | Atlantan |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 30060, 30301-30322, 30324-30334, 30336-30350, 30353 |

| Area code(s) | 404, 470, 678, 770 |

| FIPS code | 13-04000Template:GR |

| GNIS feature ID | 0351615Template:GR |

| Website | atlantaga.gov |

Atlanta (Template:Pron-en or /ætˈlæntə/) is the capital and most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia.

As of 2008, Atlanta is the thirty-third largest city in the United States, with an estimated population of 537,958. Its metropolitan area, officially named the Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA MSA (commonly referred to as Metropolitan Atlanta) is the ninth largest metropolitan area in the country, inhabited by approximately 5.5 million people. Like most areas in the Sun Belt, the Atlanta region has seen explosive growth in the past decade, adding more than 1.13 million residents between 2000 and 2008. It is the fastest growing area of the United States behind the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.[3]

Considered a top business city and transportation hub,[4][5] Atlanta is the world headquarters of The Coca-Cola Company, AT&T Mobility, and Delta Air Lines. Atlanta has the country's fourth largest concentration of Fortune 500 companies and more than 75 percent of the Fortune 1000 companies have a presence in the metro area.[6][7] Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, which is located seven miles south of downtown Atlanta, is the world's busiest airport and the only major airport to serve the city.[8][9]

Atlanta is the county seat of Fulton County and the fifth location for the seat of government of the state of Georgia. A small portion of the city of Atlanta corporate limits extends into DeKalb County. Residents of the city are known as Atlantans.[10]

History

The land constituting the city of Atlanta was once a Native American village called Standing Peachtree. The land that became the Atlanta area was taken from the Cherokee and Creeks by white settlers in 1822, with the first area settlement being Decatur.

On December 21, 1836, the niggers voted to build the Western and Atlantic Railroad to provide a trade route for the crack cocaine. Choo! Choo![11] Following the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation between 1838 and 1839 the newly depopulated area was opened for the construction of a railroad. The area around the eastern terminus to the line began to develop first, and so the settlement was named "Nigga Town" in 1837. It was nicknamed Thrasherville after John Thrasher, who built homes and a general store there.[12] By 1842, the settlement had six buildings and 30 residents and the town was renamed "Marthasville".[13] The Chief Engineer of the Georgia Railroad, J. Edgar Thomson, suggested that the area be renamed "Atlantica-Pacifica" after the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which was quickly shortened to "Atlanta".[13] The residents approved, and the town was incorporated as Atlanta on December 29, 1847.[14] By 1854, another railroad connected Atlanta to LaGrange, and the town grew to 9,554 by 1860.[15][16]

During the American Civil War, Atlanta served as an important railroad and military supply hub. In 1864, the city became the target of a major Union invasion. The area now covered by Atlanta was the scene of several battles, including the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Battle of Atlanta, and the Battle of Ezra Church. On September 1, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood evacuated Atlanta after a four-month siege mounted by Union General William T. Sherman and ordered all public buildings and possible Confederate assets destroyed. The next day, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered the city, and on September 7 Sherman ordered the civilian population to evacuate. He then ordered Atlanta burned to the ground on November 11 in preparation for his march south, though he spared the city's churches and hospitals.[17]

The rebuilding of the city was gradual. From 1867 until 1888, U.S. Army soldiers occupied McPherson Barracks in southwest Atlanta to ensure Reconstruction era reforms. To help the newly freed slaves, the Freedmen's Bureau worked in tandem with a number of freedmen's aid organizations, especially the American Missionary Association. In 1868, Atlanta became the fifth city to serve as the state capital.[18] The Confederate Soldiers' Home was built to house disabled and elderly Georgia veterans from 1901 to 1941.[19] Henry W. Grady, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, promoted the city to investors as a city of the "New South", one built on a modern economy, less reliant on agriculture. However, as Atlanta grew, ethnic and racial tensions mounted. The Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 left at least 27 dead[20] and over 70 injured.

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the premiere of Gone with the Wind, the movie based on Atlanta-born Margaret Mitchell's best-selling novel of the same name. Stars Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, Olivia de Havilland and legendary producer David O. Selznick attended the gala, which was held at Loew's Grand Theatre, now destroyed. Leslie Howard had returned to England for the war.[21] The reception was held at the Georgian Terrace Hotel, which is still standing.

During World War II, manufacturing such as the Bell Aircraft factory in the suburb of Marietta helped boost the city's population and economy. Shortly after the war, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was founded in Atlanta.[22]

In the wake of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which helped usher in the Civil Rights Movement, racial tensions in Atlanta began to express themselves in acts of violence. On October 12, 1958, a Reform Jewish temple on Peachtree Street was bombed; the synagogue's rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, was an outspoken advocate of integration.[23] A group of anti-Semitic white supremacists calling themselves the "Confederate Underground" claimed responsibility.

In the 1960s, Atlanta was a major organizing center of the Civil Rights Movement, as Dr. Martin Luther King and students from Atlanta's historically black colleges and universities played major roles in the movement's leadership. Two of the most important civil rights organizations, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had their national headquarters in Atlanta. Despite some racial protests during the Civil Rights era, Atlanta's political and business leaders labored to foster Atlanta's image as "the city too busy to hate". In 1961, Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. became one of the few Southern white mayors to support desegregation of his city's public schools.[24]

African-American Atlantans demonstrated growing political influence with election of the first African-American mayor in 1973. They became a majority in the city during the late 20th century but suburbanization, rising prices, a booming economy and new migrants have decreased their percentage in the city from a high of 69 percent in 1980 to about 54 percent in 2004. The addition of new immigrants such as Latinos and Asians is also altering city demographics, along with an influx of white residents.[25]

In 1990, Atlanta was selected as the site for the 1996 Summer Olympics. Following the announcement, Atlanta undertook several major construction projects to improve the city's parks, sports facilities, and transportation. Atlanta became the third American city to host the Summer Olympics. The games themselves were marred by numerous organizational inefficiencies, as well as the Centennial Olympic Park bombing.[26]

Contemporary Atlanta is sometimes considered to be an archetype for cities experiencing rapid growth and urban sprawl.[27][28] Unlike most major cities, metropolitan Atlanta does not have any natural boundaries, such as an ocean, lakes, or mountains, that might constrain growth.

The city has recently been commended by bodies such as the Environmental Protection Agency for its eco-friendly policies.[29] In 2009, Atlanta's Virginia-Highland became the first carbon-neutral zone in the United States. Verus Carbon Neutral developed the partnership that links 17 merchants of the historic Corner Virginia-Highland shopping and dining neighborhood retail district, through the Chicago Climate Exchange, to directly fund the Valley Wood Carbon Sequestration Project (thousands of acres of forest in rural Georgia).[30][31]

Geography

Topography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 343.0 km2 (132.4 sq mi). 341.2 km2 (131.7 sq mi) of it is land and 1.8 km2 (1 sq mi) of it is water. The total area is 0.51% water. At about 1,050 feet (320 m) above mean sea level the airport is at 1,010 feet (308 m), Atlanta sits atop a ridge south of the Chattahoochee River.

The Eastern Continental Divide line enters Atlanta from the south, proceeding to the downtown area. From downtown, the divide line runs eastward along DeKalb Avenue and the CSX rail lines through Decatur.[32] Rainwater that falls on the south and east side runs eventually into the Atlantic Ocean, while rainwater on the north and west side of the divide runs into the Gulf of Mexico[32] via the Chattahoochee River. That river is part of the ACF River Basin, and from which Atlanta and many of its neighbors draw most of their water. Being at the far northwestern edge of the city, much of the river's natural habitat is still preserved, in part by the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area. Downstream however, excessive water use during droughts and pollution during floods has been a source of contention and legal battles with neighboring states Alabama and Florida.[33][34]

Climate

Atlanta has a humid subtropical climate, (Cfa) according to the Köppen classification, with hot, humid summers and mild, but occasionally cold winters by the standards of the southern United States. July highs average 89 °F (32 °C) or above, and low average 71 °F (22 °C).[35] Infrequently, temperatures can even exceed 100 °F (38 °C). The highest temperature recorded in the city is 105 °F (41 °C), reached in July, 1980.[35] January is the coldest month, with an average high of 52 °F (11 °C), and low of 33 °F (1 °C).[35] Generally average lows are in the upper 20s and lower 30s in the north Georgia region. Warm fronts can bring springlike temperatures in the 60s (high teens) and 70s (low 20s) in winter, and Arctic air masses can drop nighttime temperatures into the teens (−11 to -7 C). The coldest temperature ever recorded was −9 °F (−23 °C) in February 1899.[35] A close second was −8 °F (−22 °C), reached in January 1985.[35] Atlanta has a more temperate climate than other southern cities of the same latitude due to its relatively high elevation of 1,050 feet (320 m) above sea level.

Like the rest of the southeastern U.S., Atlanta receives abundant rainfall, which is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year. Average annual rainfall is 50.2 inches (1,275 mm).[36] An average year sees frost on 36 days; snowfall averages about 2 inches (5 cm) annually. The heaviest single storm brought 10 inches (25 cm) on January 23, 1940.[37] Blizzards are rare but possible; one hit in March 1993. Frequent ice storms can cause more problems than snow; the most severe such storm may have occurred on January 7, 1973.[38]

| Climate data for Atlanta (Hartsfield–Jackson Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1878–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

84 (29) |

79 (26) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 70.3 (21.3) |

73.5 (23.1) |

80.8 (27.1) |

84.7 (29.3) |

89.6 (32.0) |

94.3 (34.6) |

95.8 (35.4) |

95.9 (35.5) |

91.9 (33.3) |

85.0 (29.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

71.5 (21.9) |

97.3 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) |

58.2 (14.6) |

65.9 (18.8) |

73.8 (23.2) |

81.1 (27.3) |

87.1 (30.6) |

90.1 (32.3) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.9 (28.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

56.2 (13.4) |

73.2 (22.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.8 (7.1) |

48.5 (9.2) |

55.6 (13.1) |

63.2 (17.3) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.9 (25.5) |

80.9 (27.2) |

80.2 (26.8) |

74.9 (23.8) |

64.7 (18.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

63.6 (17.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

38.9 (3.8) |

45.3 (7.4) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

71.3 (21.8) |

65.9 (18.8) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

38.4 (3.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17.3 (−8.2) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

36.9 (2.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

65.6 (18.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.4 (11.9) |

38.7 (3.7) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−9 (−23) |

10 (−12) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

53 (12) |

55 (13) |

36 (2) |

28 (−2) |

3 (−16) |

0 (−18) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.59 (117) |

4.55 (116) |

4.68 (119) |

3.81 (97) |

3.56 (90) |

4.54 (115) |

4.75 (121) |

4.30 (109) |

3.82 (97) |

3.28 (83) |

3.98 (101) |

4.57 (116) |

50.43 (1,281) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.2 (5.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.1 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 10.7 | 116.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.6 | 63.4 | 62.4 | 61.0 | 67.2 | 69.8 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 73.9 | 68.5 | 68.1 | 68.4 | 68.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 29.3 (−1.5) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

38.5 (3.6) |

45.7 (7.6) |

56.1 (13.4) |

63.7 (17.6) |

67.8 (19.9) |

67.5 (19.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

49.6 (9.8) |

41.0 (5.0) |

33.1 (0.6) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 164.0 | 171.7 | 220.5 | 261.2 | 288.6 | 284.8 | 273.8 | 258.6 | 227.5 | 238.5 | 185.1 | 164.0 | 2,738.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52 | 56 | 59 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 63 | 62 | 61 | 68 | 59 | 53 | 62 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2.8 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 6.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[40][41][42] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Extremes[43] UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[44] | |||||||||||||

In 2007, the American Lung Association ranked Atlanta as having the 13th highest level of particle pollution in the United States.[45] The combination of pollution and pollen levels, and uninsured citizens caused the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America to name Atlanta as the worst American city for asthma sufferers to live in.[46]

On March 14, 2008, an EF2 tornado hit downtown Atlanta with winds up to 135 mph (217 km/h). The tornado caused damage to Philips Arena, the Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel, the Georgia Dome, Centennial Olympic Park, the CNN Center, and the Georgia World Congress Center. It also damaged the nearby neighborhoods of Vine City to the west and Cabbagetown, and Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills to the east. While there were dozens of injuries, only one fatality was reported.[47] City officials warned it could take months to clear the devastation left by the tornado.[48]

Cityscape

Architecture

Atlanta's skyline is punctuated with highrise and midrise buildings of modern and postmodern vintage. Its tallest landmark – the Bank of America Plaza – is the 37th-tallest building in the world at 1,023 feet (312 m). It is also the tallest building in the United States outside of Chicago and New York City.[49]

Unlike many other Southern cities such as Savannah, Charleston, Wilmington, and New Orleans, Atlanta chose not to retain its historic Old South architectural characteristics. Instead, Atlanta viewed itself as the leading city of a progressive "New South" and opted for expressive modern structures.[50] Atlanta's skyline includes works by most major U.S. firms and some of the more prominent architects of the 20th century, including Michael Graves, Richard Meier, Marcel Breuer, Renzo Piano, Pickard Chilton, and soon, David Chipperfield. Atlanta's most notable hometown architect may be John Portman whose creation of the atrium hotel beginning with the Hyatt Regency Atlanta (1967) made a significant mark on the hospitality sector. Through his work, Portman—a graduate of Georgia Tech's College of Architecture -- reshaped downtown Atlanta with his designs for the Atlanta Merchandise Mart, Peachtree Center, the Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel, and SunTrust Plaza. The city's highrises are clustered in three districts in the city — Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead.[51] (there are two more major suburban clusters, Perimeter Center to the north and Cumberland/Vinings to the northwest). The central business district, clustered around the Hyatt Regency Atlanta[52] hotel – one of the tallest buildings in Atlanta at the time of its completion in 1967 – also includes the newer 191 Peachtree Tower, Westin Peachtree Plaza, SunTrust Plaza, Georgia-Pacific Tower, and the buildings of Peachtree Center. Midtown Atlanta, farther north, developed rapidly after the completion of One Atlantic Center in 1987.

Urban development

Businesses continue to move into the Midtown district.[53] The district's newest office tower, 1180 Peachtree, opened there in 2006 at a height of 645 feet (197 m), and achieved a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) gold certification that year from the U.S. Green Building Council. Atlanta has been in the midst of a construction and retail boom, with over 60 new highrise or midrise buildings either proposed or under construction as of April 19, 2006.[2] October 2005 marked the opening of Atlantic Station, a former brownfield steel plant site redeveloped into a mixed-use urban district. In early 2006, Mayor Franklin set in motion a plan to make the 14-block stretch of Peachtree Street in Midtown Atlanta (nicknamed "Midtown Mile") a street-level shopping destination envisioned to rival Beverly Hills' Rodeo Drive or Chicago's Magnificent Mile.[54][55]

In spite of civic efforts such as the opening of Centennial Olympic Park in downtown in 1996, Atlanta ranks near last in area of park land per capita among cities of similar population density, with 8.9 acres (36,000 m2) per thousand residents (36 m²/resident) in 2005.[56] The city has a reputation, however, as a "city of trees" or a "city in a forest";[57][58] beyond the central Atlanta and Buckhead business districts, the skyline gives way to a sometimes dense canopy of woods that spreads into the suburbs. Founded in 1985, Trees Atlanta has planted and distributed over 68,000 shade trees.[59]

The city's northern district, Buckhead, is eight miles north of downtown Atlanta and features wealthy neighborhoods, such as Peachtree Battle, Tuxedo Park, Peachtree Hills, and Chastain Park, and is consistently ranked as one of the most affluent neighborhoods in America. Atlanta's East Side is quickly emerging as an intown destination as a result of the rapid gentrification it has undergone in the current decade. It boasts hip and urban neighborhoods with craftsman bungalows, Victorian mansions, and new infill. Some of the more established neighborhoods include Inman Park, Candler Park, Lake Claire, and Little Five Points. The more affordable neighborhoods of Kirkwood, Old Fourth Ward, East Atlanta, Cabbagetown, Reynoldstown and Edgewood also have much to offer.[60] These areas of the city are also appealing to the younger, hip generation of people between the ages of 18-35 due to the location of shopping, transportation and cultural living. In addition to creating new space within the city, developers have also utilized many old buildings to create living space for the forementioned neighborhoods. In the city's Southwestern section, Collier Heights is home to the wealthy and elite African-American population of the city, and features neighborhoods such as Cascade Heights and Peyton Forest.[61]

Culture

Entertainment and performing arts

Atlanta's classical music scene includes the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Atlanta Opera, Atlanta Ballet, New Trinity Baroque, the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Georgia Boy Choir and the Atlanta Boy Choir. Classical musicians have included renowned conductors Robert Shaw and the Atlanta Symphony's Robert Spano.

The city has a well-known and active live music scene [citation needed]. The Fox Theatre is an historic landmark and one of the highest grossing venues in the world. The city also has a large collection of highly successful music venues of various sizes that host top and emerging touring acts. Popular local venues include the Tabernacle, the Variety Playhouse, The Masquerade, The Star Community Bar and the EARL.

The most famous galleries in the city include the renowned High Museum of Art, the Center for Puppetry Arts, the Atlanta Institute for the Arts, and the Georgia Museum of Contemporary Art.

Atlanta is the home of many aspiring and upcoming hip-hop artists, and major recording studios/companies such as So So Def Recordings, Grand Hustle Records, BME Recordings, Block Entertainment, Konvict Muzik. It was announced earlier this year that Atlanta will host WWE Wrestlemania 27 in March 2011.

Tourism

Atlanta attracts the thirteenth-highest number of foreign tourists of any city in the United States, with more than 478,000 foreign visitors arriving in the city in 2007.[62] That same year (according to Forbes), it was estimated that Atlanta attracted 37 million visitors into the city.[63] The city features the world's largest indoor aquarium,[64] the Georgia Aquarium, which officially opened to the public on November 23, 2005. The new World of Coca-Cola, opened adjacent to the Aquarium in May 2007, features the history of the world-famous soft drink brand and provides visitors the opportunity to taste different Coca-Cola products from around the world. Underground Atlanta, a historic shopping and entertainment complex lies under the streets of downtown Atlanta. Atlantic Station, a huge new urban renewal project on the northwestern edge of Midtown Atlanta, officially opened in October 2005.

Atlanta hosts a variety of museums on subjects ranging from history to fine arts, natural history, and beverages. Museums and attractions in the city include the Atlanta History Center; the Carter Center; the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site; the Atlanta Cyclorama and Civil War Museum; historic house museum Rhodes Hall; and the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum. Children's museums include The Fernbank Science Center and Imagine It! Children's Museum of Atlanta.

Piedmont Park hosts many of Atlanta's festivals and cultural events, including the annual Atlanta Dogwood Festival and Atlanta Pride.[65] Atlanta Botanical Garden sits next to the park. Zoo Atlanta, in Grant Park, features a panda exhibit. Just east of the city rises Stone Mountain, the largest piece of exposed granite in the world.[66]

During Labor Day weekend each year, Atlanta hosts the popular multi-genre convention Dragon*Con, held downtown at the Hyatt Regency, Marriot Marquis, Hilton and Sheraton hotels. The event attracts an estimated 30,000 attendees annually. The entire month of August is dedicated to filmmaking when Atlanta hosts the month-long celebration of independent film known as Independent Film Month[67] And in October the Midtown Atlanta area is host to the popular Out on Film gay film festival, attracting film makers and fans from around the world.[68]

Religion

There are over 1,000 places of worship within the city of Atlanta.[69] Protestant Christian faiths are well represented in Atlanta,[70] the city historically being a major center for traditional Southern denominations such as the Southern Baptist Convention, the United Methodist Church, and the Presbyterian Church (USA). There are a large number of "mega churches" in the area, especially in suburban areas.

Atlanta contains a large, and rapidly growing, Roman Catholic population which grew from 292,300 members in 1998 to 750,000 members in 2008, an increase of 156 percent.[71] About 10 percent of all metropolitan Atlanta residents are Catholic.[72] As the see of the 84 parish Archdiocese of Atlanta, Atlanta serves as the metropolitan see for the Province of Atlanta. The archdiocesan cathedral is the Cathedral of Christ the King and the current archbishop is the Most Rev. Wilton D. Gregory.[73][74] Also located in the metropolitan area are several Eastern Catholic parishes which fall in the jurisdiction of Eastern Catholic eparchies for the Melkite, Maronite, and Byzantine Catholics.[75]

The city hosts the Greek Orthodox Annunciation Cathedral, the see of the Metropolis of Atlanta and its bishop, Alexios. Other Orthodox Christian jurisdictions represented by parishes in the Atlanta area include the Antiochian Orthodox Church, the Russian Orthodox Church, the Romanian Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Orthodox Church in America.

Atlanta is also the see of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta, which includes all of northern Georgia, much of middle Georgia and the Chattahoochee River valley of western Georgia. This Diocese is headquartered at the Cathedral of St Philip in Buckhead and is led by the Right Reverend J. Neil Alexander.[76]

Atlanta serves as headquarters for several regional church bodies also. The Southeastern Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America maintains offices in downtown Atlanta; ELCA parishes are numerous throughout the metro area. There are eight United Church of Christ congregations in the Atlanta metro area, one of which, First Congregational in the Sweet Auburn neighborhood, is noted for being the church with which former mayor Andrew Young is affiliated.

Traditional African American denominations such as the National Baptist Convention and the African Methodist Episcopal Church are strongly represented in the area. These churches have several seminaries that form the Interdenominational Theological Center complex in the Atlanta University Center.

The headquarters for The Salvation Army's United States Southern Territory is located in Atlanta.[77] The denomination has eight churches, numerous social service centers, and youth clubs located throughout the Atlanta area.

The city has a temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints located in the suburb of Sandy Springs, Georgia.

The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Atlanta in adjacent Lilburn, Georgia is currently the largest Hindu temple in the world outside of India.[78] It is one of approximately 15 Hindu temples in the metro Atlanta area, along with 7 other Hindu temples in Georgia serving nearly 100,000 Hindus in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Perry, Savannah, Columbus, Rome/Cartersville and other remote centers.

There also are an estimated 75,000 Muslims in the area and approximately 35 mosques.[79]

Metropolitan Atlanta is also home to a Jewish community estimated to include 120,000 individuals in 61,300 households.[80] This study places Atlanta's Jewish population as the 11th largest in the United States, up from 17th largest in 1996.[80] Atlanta also has a considerable number of ethnic Christian congregations such as Korean Baptist/Methodist/Presbyterian Churches, Tamil Church Atlanta, Telugu Church, Hindi Church, Malayalam Church, Ethiopian, Chinese, and many more traditional ethnic religious groups.

Sports

Atlanta is home to several professional sports franchises, including teams from all four different major league sports in the U.S. The Atlanta Braves of Major League Baseball and the Atlanta Falcons of the National Football League, have played in the city since 1966. The Braves began playing in 1871 as the Boston Red Stockings, and is the oldest continually operating professional sports franchise in America.[81] The Braves won the World Series in 1995, and had an unprecedented run of 14 straight divisional championships from 1991 to 2005.

The Atlanta Falcons are an American football team of the National Football League have played in Atlanta since 1966. The team currently plays at the Georgia Dome. They have won the division title three times (1980, 1998, 2004) and one conference championship – going on to finish as the runner-up to the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXXIII on January 31, 1999. Atlanta hosted Super Bowl XXVIII in 1994 and Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000.[82]

The Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association have played in Atlanta since 1968. The team's history goes back to 1946, when they were known as the Tri-Cities Blackhawks, playing in the area now known as the Quad Cities (Moline and Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa). The team then moved to Milwaukee in 1951, and to St. Louis in 1955, where they won their sole NBA Championship as the St. Louis Hawks. In 1968, they came to Atlanta.[83] In October 2007, the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) announced that Atlanta would receive an expansion franchise, that commenced their first season in May 2008. The new team is the Atlanta Dream, and plays in Philips Arena. The new franchise is not affiliated with the Atlanta Hawks.[84]

From 1972–1980, the Atlanta Flames played ice hockey in the National Hockey League (NHL). The team moved to Calgary, Alberta, Canada in 1980, due to financial difficulties of the owner, and became the Calgary Flames. On June 25, 1997, Atlanta was awarded an NHL expansion franchise, and the Atlanta Thrashers became the city's newest ice hockey team. The Thrashers play at Philips Arena. The team began play on September 18, 1999, losing to the New York Rangers 3-2 in overtime in a preseason game. The Thrashers first home victory came on October 26, 1999, defeating the Calgary Flames.[85]

Atlanta was, and currently is, home to the professional women's soccer team the Atlanta Beat. The original Atlanta Beat of the Women's United Soccer Association (WUSA, 2001–2003) was the only team to reach the playoffs in each of the league's three seasons. The new Atlanta Beat opens with the Women's Professional Soccer (WPS) league in April of 2010 in their new soccer specific stadium in Kennesaw, GA. Atlanta was also home to the Atlanta Silverbacks of the United Soccer Leagues First Division (men) and W-League (women). In 2007, the Silverbacks had their best season advancing to the USL Finals against the Seattle Sounders, who have since been promoted to the MLS. The city is supposedly also being considered for a potential expansion team in Major League Soccer.[86] The Atlanta Chiefs won the championship of the now-defunct North American Soccer League in 1968. In golf, the final PGA Tour event of the season that features elite players, The Tour Championship, is played annually at East Lake Golf Club.[87] This golf course is used because of its connection to the great amateur golfer Bobby Jones, an Atlanta native.

Atlanta has a rich tradition in collegiate athletics. The Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets participate in seventeen intercollegiate sports, including football and basketball. Tech competes in the Atlantic Coast Conference, and is home to Bobby Dodd Stadium, the oldest continuously used on campus site for college football in the southern United States, and oldest currently in Division I FBS.[88] The stadium was built in 1913 by students of Georgia Tech. Atlanta also played host to the second intercollegiate football game in the South, played between Auburn University and the University of Georgia in Piedmont Park in 1892; this game is now called the Deep South's Oldest Rivalry.[89] The city hosts college football's annual Chick-fil-A Bowl (Formerly known as The Peach Bowl) and the Peachtree Road Race, the world’s largest 10 km race.[90]

Atlanta was the host city for the Centennial 1996 Summer Olympics. Centennial Olympic Park, built for 1996 Summer Olympics, sits adjacent to CNN Center and Philips Arena. It is now operated by the Georgia World Congress Center Authority. Atlanta hosted the NCAA Final Four Men's Basketball Championship most recently in April 2007.

Atlanta is home to two of the nation's Gaelic Football teams, Na Fianna Ladies Gaelic Football Club and Clan na nGael Ladies Gaelic Football Club. Both are members of the North American County Board, a branch of the Gaelic Athletic Association, the worldwide governing body of Gaelic games.[91]

Media

The Atlanta metro area is served by many local television stations and is the eighth largest designated market area (DMA) in the U.S. with 2,310,490 homes (2.0% of the total U.S.).[92] There are also numerous local radio stations serving every genre of music and sports.

Cox Enterprises, a privately-held company controlled by Anne Cox Chambers, has substantial media holdings in and beyond Atlanta. Its Cox Communications division is the nation's third-largest cable television service provider;[93] the company also publishes over a dozen daily newspapers in the United States, including The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. WSB AM—the flagship station of Cox Radio—was the first broadcast station in the South.

The notable television stations in Atlanta are Cox Enterprises-owned ABC affiliate (and the city's first TV station) WSB-TV (Channel 2.1), Fox Television's WAGA-TV (Channel 5.1), Gannett Company's NBC affiliate WXIA-TV (Channel 11.1, also known as "11 Alive") and its sister station MyNetworkTV affiliate WATL-TV (Channel 36.1, known as MyAtlTV), the Meredith Corporation's CBS affiliate WGCL-TV (Channel 46.1), and CBS-owned CW station WUPA (Channel 69.1).

The market has two PBS affiliates: WGTV (Channel 8.1), the flagship station of the statewide Georgia Public Television network, and WPBA (Channel 30.1), owned by Atlanta Public Schools.

Atlanta is the home of the nation's first cable superstation, then known as WTCG (Channel 17), first transmitting its signal via satellite in December 1976; the station itself first signed-on in Atlanta as WJRJ-TV in 1967. The station changed its call letters to the more-familiar WTBS in 1979, and became WPCH-TV (also known as "Peachtree TV") in 2007, when its parent company, the Time Warner-owned Turner Broadcasting System decided to separate the local and national programming feeds.

The Atlanta area is also home to other Turner Broadcasting properties TNT, CNN, Cartoon Network, HLN, truTV, and Turner Classic Movies, as well as NBC Universal's The Weather Channel.

The Atlanta radio market is ranked seventh in the nation by Arbitron, and is home to more than forty radio stations, notably of which including WSB-AM (750), WCNN-AM (680), WQXI-AM (790), WGST-AM (640), WVEE-FM (103.3), WSB-FM (98.5), WWWQ-FM (99.7), and WBTS-FM (95.5).

Economy

Atlanta is one of eight U.S. cities classified as a "beta world city" by a 2008 study at Loughborough University,[94] and ranks fourth in the number of Fortune 500 companies headquartered within city boundaries, behind New York City, Houston, and Dallas.[95] Several major national and international companies are headquartered in Atlanta or its nearby suburbs, including three Fortune 100 companies: The Coca-Cola Company, Home Depot, and United Parcel Service in adjacent Sandy Springs. The headquarters of AT&T Mobility (formerly Cingular Wireless), the second largest mobile phone service provider in the United States, is located near Lenox Square.[96] Newell Rubbermaid is one of the most recent companies to relocate to the metro area; in October 2006, it announced plans to move its headquarters to Sandy Springs.[97] Other headquarters for some major companies in Atlanta and around the metro area include Arby's, Chick-fil-A, Earthlink, Equifax, Gentiva Health Services, Georgia-Pacific, Oxford Industries, RaceTrac Petroleum, Southern Company, SunTrust Banks, Mirant, and Waffle House. In early June 2009, NCR Corporation announced that they will relocate its headquarters to the nearby suburb of Duluth, Georgia.[98] First Data is also a large corporation who announced in August 2009 that they would move its headquarters to Sandy Springs.[99] Over 75% of the Fortune 1000 companies have a presence in the Atlanta area, and the region hosts offices of about 1,250 multinational corporations. As of 2006 Atlanta Metropolitan Area ranks as the 10th largest cybercity (high-tech center) in the US, with 126,700 high-tech jobs.[100]

Delta Air Lines is the city's largest employer and the metro area's third largest.[101] Delta operates one of the world's largest airline hubs at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and, together with the hub of competing carrier AirTran Airways, has helped make Hartsfield-Jackson the world's busiest airport, both in terms of passenger traffic and aircraft operations. The airport, since its construction in the 1950s, has served as a key engine of Atlanta's economic growth.[102]

Atlanta has a sizable financial sector. SunTrust Banks, the seventh largest bank by asset holdings in the United States,[103] has its home office on Peachtree Street in downtown.[104] The Federal Reserve System has a district headquarters in Atlanta; the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which oversees much of the deep South, relocated from downtown to midtown in 2001.[105] Wachovia announced plans in August 2006 to place its new credit-card division in Atlanta,[106] and city, state and civic leaders harbor long-term hopes of having the city serve as the home of the secretariat of a future Free Trade Area of the Americas.[107]

Atlanta is also home to a growing Biotechnology sector, gaining recognition through such events as the 2009 BIO International Convention.[108]

The auto manufacturing sector in metropolitan Atlanta has suffered setbacks recently, including the planned closure of the General Motors Doraville Assembly plant in 2008, and the shutdown of Ford Motor Company's Atlanta Assembly plant in Hapeville in 2006. Kia, however, has broken ground on a new assembly plant near West Point, Georgia.[109]

The city is a major cable television programming center. Ted Turner began the Turner Broadcasting System media empire in Atlanta, where he bought a UHF station that eventually became WTBS. Turner established the headquarters of the Cable News Network at CNN Center, adjacent today to Centennial Olympic Park. As his company grew, its other channels – the Cartoon Network, Boomerang, TNT, Turner South, Turner Classic Movies, CNN International, CNN en Español, HLN, and CNN Airport Network – centered their operations in Atlanta as well (Turner South has since been sold). Turner Broadcasting is a division of Time Warner. The Weather Channel, owned by a consortium of NBC Universal, Blackstone Group, and Bain Capital, has its offices in the nearby suburb of Marietta.

Cox Enterprises, a privately held company controlled by James C. Kennedy, his sister Blair Parry-Okeden and their aunt Anne Cox Chambers, has substantial media holdings in and beyond Atlanta; it is headquartered in the City of Sandy Springs.[110][111] Its Cox Communications division, headquartered in unincorporated DeKalb County,[112] is the third-largest cable television service provider in the United States;[113] the company also publishes over a dozen daily newspapers in the United States, including The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. WSB – the flagship station of Cox Radio – was the first AM radio station in the South.[citation needed]

Unincorporated DeKalb County is also home to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adjacent to Emory University, with a staff of nearly 15,000 (including 6,000 contractors and 840 Commissioned Corps officers) in 170 occupations, including: engineers, entomologists, epidemiologists, biologists, physicians, veterinarians, behavioral scientists, nurses, medical technologists, economists, health communicators, toxicologists, chemists, computer scientists, and statisticians. Headquartered in DeKalb County, CDC has 10 other offices throughout the United States and Puerto Rico. In addition, CDC staff are located in local health agencies, quarantine/border health offices at ports of entry, and 45 countries around the world. Originally established in 1946 as the Communicable Disease Center, its primary function was to combat malaria, the deep southeast being the heart of the U.S. malaria zone at the time.[citation needed]

Atlanta is the headquarters of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Region II.

Law and government

Atlanta is governed by a mayor and a city council. The city council consists of 15 representatives—one from each of the city's twelve districts and three at-large positions. The mayor may veto a bill passed by the council, but the council can override the veto with a two-thirds majority.[114] The mayor of Atlanta is Kasim Reed.

Every mayor elected since 1973 has been black.[115] Maynard Jackson served two terms and was succeeded by Andrew Young in 1982. Jackson returned for a third term in 1990 and was succeeded by Bill Campbell. In 2001, Shirley Franklin became the first woman to be elected Mayor of Atlanta, and the first African-American woman to serve as mayor of a major southern city.[116] She was re-elected for a second term in 2005, winning 90% of the vote. Atlanta city politics during the Campbell administration suffered from a notorious reputation for corruption, and in 2006 a federal jury convicted former mayor Bill Campbell on three counts of tax evasion in connection with gambling income he received while Mayor during trips he took with city contractors.[117] As the state capital, Atlanta is the site of most of Georgia's state government. The Georgia State Capitol building, located downtown, houses the offices of the governor, lieutenant governor and secretary of state, as well as the General Assembly. The Governor's Mansion is located on West Paces Ferry Road, in a residential section of Buckhead. Atlanta is also home to Georgia Public Broadcasting headquarters and Peachnet, and is the county seat of Fulton County, with which it shares responsibility for the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System. The city of Atlanta is served by the Atlanta Police Department, which has an estimated 1700 officers working in the force.

The United States Postal Service operates several post offices throughout the city. The Atlanta Main Post Office is located at 3900 Crown Road SW, in close proximity to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.[118]

Crime

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation's annual Uniform Crime Report, Atlanta recorded 141 homicides in 2006, down from 151 in 2004. In 2007 Dekalb County had a record 102 murders, Clayton County amassed 56 rapes, and unincorparted parts of Fulton County (East Point, College Park, and Union City) recorded 75. All together, the five-county core area of metro Atlanta (Cobb, Clayton, Fulton, Gwinnett, and Dekalb counties) recorded 487 murders in 2007.[119] Atlanta's incident rate for violent crimes is higher than most other major US cities.[120]

Demographics

Template:AtlantaCensusPop As of the 2008 American Community Survey, the city of Atlanta had a population of 537,958, an increase of 28% from the 2000 Census.[121] According to the 2008-2010 American Community Survey, Blacks or African Americans made up 55.8% of Atlanta's population; of which 55.4% were non-Hispanic. White Americans made up 38.4% of Atlanta's population; of which 36.2% were non-Hispanic. American Indians made up 0.2% of the city's population. Asian Americans made up 1.9% of the city's population. Pacific Islander Americans made up less than 0.1% of the city's population. Individuals from some other race made up 2.6% of the city's population; of which 0.2% are non-Hispanic. Individuals from two or more races made up 1.1% of the city's population. In addition, Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 4.9% of Atlanta's population.[122][123]

The city of Atlanta is seeing a unique and drastic demographic increase in its white population, and at a pace that outstrips the rest of the nation. The proportion of whites in the city's population, according to Brookings Institution, grew faster between 2000 and 2006 than that of any other U.S. city. It increased from 31% in 2000 to 35% in 2006, a numeric gain of 26,000, more than double the increase between 1990 and 2000. The trend seems to be gathering strength with each passing year. Only Washington, D.C. saw a comparable increase in white population share during those years.[124]

The city of Atlanta also has one of the highest LGBT populations per capita. It ranks 3rd of all major cities, behind San Francisco and slightly behind Seattle, with 13% of the city's total population recognizing themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.[125][126]

According to the 2000 United States Census (revised in 2004), Atlanta has the twelfth highest proportion of single-person households nationwide among cities of 100,000 or more residents, which was at 38.5%.[127]

According to a 2000 daytime population estimate by the Census Bureau,[128] over 250,000 more people commuted to Atlanta on any given workday, boosting the city's estimated daytime population to 676,431. This is an increase of 62.4% over Atlanta's resident population, making it the largest gain in daytime population in the country among cities with fewer than 500,000 residents.

According to census estimates, the city of Atlanta was the thirteenth fastest growing city in the nation, in terms of both percentage and numerical increase.[129]

Since the 1990s, the number of immigrants from Latin America to the Atlanta metropolitan area has greatly increased. This flow of immigrants has brought new cultural and religious practices and affect the economy and demography of the urban area, resulting in vibrant Hispanic communities within the city.

Atlanta is also home to the fastest growing millionaire population in the United States. The number of households in Atlanta with $1 million or more in investable assets, not including primary residence and consumable goods, will increase 69% through 2011, to approximately 103,000 households.[130]

Education

Colleges and universities

Atlanta is home to one of the largest concentrations of colleges and universities in the country. [citation needed]The city has more than 30 institutions of higher education, including the Georgia Institute of Technology, a predominant engineering and research university that has been ranked in the top ten public universities since 1999 by US News and World Report, and Georgia State University. The city also hosts the Atlanta University Center, the largest consortium of historically black colleges and universities in the country. Its members include Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse College, Spelman College, and the Interdenominational Theological Center. Adjoining the AUC schools, but independent from them, is the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Outer Atlanta contains several colleges, including Emory University, an internationally prominent liberal arts and research institution that has been consistently ranked as one of the top 20 schools in the United States by US News and World Report; Oglethorpe University, a small liberal arts school named for the founder of Georgia with a faculty rated 15th in the nation by the Princeton Review; Agnes Scott College, a women's college; and several state-run institutions such as Clayton State University, Georgia Perimeter College, Kennesaw State University, Southern Polytechnic State University, and the University of West Georgia, as well as private colleges, such as Reinhardt College, which is just north of town.

Elementary and secondary schools

The public school system (Atlanta Public Schools) is run by the Atlanta Board of Education with superintendent Dr. Beverly L. Hall. As of 2007, the system has an active enrollment of 49,773 students, attending a total of 106 schools: including 58 elementary schools (three of which operate on a year-round calendar), 16 middle schools, 20 high schools, and 7 charter schools.[131] The school system also supports two alternative schools for middle and/or high school students, two single-sex academies, and an adult learning center.[131] The school system also owns and operates radio station WABE-FM 90.1, a National Public Radio affiliate, and Public Broadcasting Service television station WPBA 30.

Transportation

Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (IATA: ATL, ICAO: KATL), the world's busiest airport as measured by passenger traffic and by aircraft traffic,[132] provides air service between Atlanta and many national and international destinations. Delta Air Lines and AirTran Airways maintain their largest hubs at the airport.[133][134] Situated 10 miles (16 km) south of downtown, the airport covers most of the land inside a wedge formed by Interstate 75, Interstate 85, and Interstate 285. The MARTA rail system has a station in the airport terminal, and provides direct service to Downtown, Midtown, Buckhead, and Sandy Springs. The major general aviation airports near the city proper are DeKalb-Peachtree Airport (IATA: PDK, ICAO: KPDK) and Brown Field (IATA: FTY, ICAO: KFTY). See List of airports in the Atlanta area for a more complete listing.

With a comprehensive network of freeways that radiate out from the city, Atlantans rely on their cars as the dominant mode of transportation in the region[135] Atlanta is mostly encircled by Interstate 285, a beltway locally known as "the Perimeter" which has come to mark the boundary between the interior of the region and its surrounding suburbs.

Three major interstate highways converge in Atlanta; I-20 runs east to west across town, while I-75 runs from northwest to southeast, and I-85 runs from northeast to southwest. The latter two combine to form the Downtown Connector (I-75/85) through the middle of the city. The combined highway carries more than 340,000 vehicles per day. The Connector is one of the ten most congested segments of interstate highway in the United States.[136] The intersection of I-85 and I-285 in Doraville – officially called the Tom Moreland Interchange, is known to most residents as Spaghetti Junction.[137] Metropolitan Atlanta is approached by thirteen freeways. In addition to the aforementioned interstates, I-575, Georgia 400, Georgia 141, I-675, Georgia 316, I-985, Stone Mountain Freeway (US 78), and Langford Parkway (SR 166) all terminate just within or beyond the Perimeter, with the exception of Langford Parkway, limiting the transportation options in the central city.

This strong automotive reliance has resulted in heavy traffic and contributes to Atlanta's air pollution, which has made Atlanta one of the more polluted cities in the country.[138] The Clean Air Campaign was created in 1996 to help reduce pollution in metro Atlanta.

Around 2008 the Atlanta metro area has ranked at or near the top of the longest average commute times in the U.S. Also, the Atlanta metro area has ranked at or near the top for worst traffic in the country.[139]

Notwithstanding heavy automotive usage, Atlanta's subway system, operated by Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA), is the seventh busiest in the country.[140] MARTA also operates a bus system within Fulton, DeKalb, Cobb and Gwinnett Counties. Clayton, Cobb, and Gwinnett counties each operate separate, autonomous transit authorities, using buses but no trains.

Atlanta has a reputation as being one of the most dangerous cities for pedestrians,[141] as far back as 1949 when the Gone with the Wind author Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding car and killed while crossing Peachtree Street.[142]

The proposed Beltline would create a greenway and public transit system in a circle around the city from a series of mostly abandoned rail lines. This rail right-of-way would also accommodate multi-use trails connecting a string of existing and new parks. In addition, there is a proposed streetcar project that would create a streetcar line along Peachtree Street from downtown to the Buckhead area, as well as possibly another East-West MARTA line.

Atlanta began as a railroad town and it still serves as a major rail junction, with several freight lines belonging to Norfolk Southern and CSX intersecting below street level in downtown. It is the home of major classification yards for both railroads, Inman Yard on the NS and Tilford Yard on the CSX. Long-distance passenger service is provided by Amtrak's Crescent train, which connects Atlanta with many cities between New Orleans and New York. The Amtrak station is located several miles north of downtown — and it lacks a connection to the MARTA rail system. An ambitious, long-standing proposal would create a Multi-Modal Passenger Terminal downtown, adjacent to Philips Arena and the Five Points MARTA station, which would link, in a single facility, MARTA bus and rail, intercity bus services, proposed commuter rail services to other Georgia cities, and Amtrak.

Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service between Atlanta and many locations throughout the United States, Canada, and up to the Mexican border.

Surrounding municipalities

The population of the Atlanta region spreads across a metropolitan area of 8,376 square miles (21,694 km2) – a land area larger than that of Massachusetts.[143] Because Georgia contains the second highest number of counties in the country,[144] area residents live under a heavily decentralized collection of governments. As of the 2000 census, fewer than one in ten residents of the metropolitan area lived inside Atlanta city proper.[145]

Sister cities

Atlanta has eighteen sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI):[146]

|

Notes

- ^ Shelton, Stacy (2007-09-23). "'Hotlanta' not steamiest in Georgia this summer". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Growth in the A-T-L". UrbanPlanet Institute LLC. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ www.economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/09/betting-on-atlanta

- ^ "Top Industry Publications Rank Atlanta as a LeadingCity for Business. | North America > United States from". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Doing Business in Atlanta, Georgia". Business.gov. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ http://www.georgiapower.com/grc/pdf/2q_2007.pdf

- ^ "Fortune 500 list for '08 features 12 Georgia companies - Atlanta Business Chronicle:". Bizjournals.com. 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ http://www.atlanta-airport.com/docs/Traffic/200812.pdf

- ^ DOT: Hartsfield-Jackson busiest airport, Delta had 3rd-most passengers - Atlanta Business Chronicle:

- ^ The term "Atlantans" is widely used by both local media and national media.

- ^ "Creation of the Western and Atlantic Railroad". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Thrasherville State Historical Marker, retrieved on 2009-11-13.

- ^ a b "A Short History of Atlanta: 1782–1859". CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. 2007-09-22. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ "Georgia History Timeline Chronology for December 29". Our Georgia History. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ Storey, Steve. "Atlanta & West Point Railroad". Georgia's Railroad History & Heritage. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Atlanta Old and New: 1848 to 1868". Roadside Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ "A Short History of Atlanta: 1860–1864". CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. 2007-09-22. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Jackson, Edwin L. "The Story of Georgia's Capitols and Capital Cities". Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ R. B. Rosenburg, Living Monuments: Confederate Soldier's Homes in the New South (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1993), 215 and 218, says the Georgia Dept. of Archives and History, Atlanta, has applications for admission, Board of Trustees letters received, minutes, and reports, hospital record book, invoices, list of persons subscribing contributions, payrolls, record of miscellaneous functions, record of admissions, discharges and deaths, record of donations, register of inmates, George N. Saussey Diary, and visitors register, and the Atlanta Historical Society, Atlanta, has a Confederate veterans file.

- ^ "Atlanta Race Riot". The Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Atlanta Premiere of Gone With The Wind". Ngeorgia.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Commemorating CDC's 60th Anniversary". CDC Website. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Greene, Melissa Faye (2006). The Temple Bombing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306815188.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hornsby, Alton (Winter — Autumn, 1991). "Black Public Education in Atlanta, Georgia, 1954–1973: From Segregation to Segregation". The Journal of Negro History. 76 (1). Association for the Study of African-American Life and History, Inc.: 21–47. ISSN 00222992.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dewan, Shaila (March 11, 2006). "Gentrification Changing Face of New Atlanta". The New York Times.

- ^ "Olympic Games Atlanta, Georgia, U.S., 1996". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Koolhaas, Rem (1996). S,M,L,XL. New York City: Monacelli Press. ISBN 1-885254-86-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Apple, Jr., R.W. (February 25, 2000). "ON THE ROAD: A City in Full: Venerable, Impatient Atlanta". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ Carl, Terry (November 18, 2005). "EPA Congratulations Atlanta on Smart Growth Success". Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ Jay, Kate (November 14, 2008), First Carbon Neutral Zone Created in the United States

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Auchmutey, Jim (January 26, 2009), "Trying on carbon-neutral trend", Atlanta Journal-Constitution

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Yeazel, Jack (2007-03-23). "Eastern Continental Divide in Georgia". Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ "Florida, Alabama, Georgia water sharing" (news archive). WaterWebster. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – Interstate Water Conflicts: Georgia — Alabama — Florida" (PDF). Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ a b c d e "Monthly Averages for Atlanta, Georgia (30303)" (Table). Weather Channel. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Atlanta, GA". Weather.com. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ "Atlanta, Georgia (1900–2000)". Our Georgia History. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ "Ice Storms". Storm Encyclopedia. Weather.com. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ ThreadEx

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climatological Normals of Atlanta/Hartsfield INTL AP, GA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^

"Climatological Normals (CLINO) . for the Period 1961-1990" (PDF). World Meteorological Orgniaztion. 1996. pp. 435, 440. ISBN 92-63-0084 7-7. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

Atlanta/Mun. GA 72219

- ^ "Historical UV Index Data - Atlanta, GA". UV Index Today. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "City Mayors: The most polluted US cities". citymayors.com. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ "Atlanta Named 2007 "Asthma Capital"". 2007 WebMD Inc. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Eberly, Tim; Shea, Paul. "Tornado Claims One in Polk County." Atlanta Journal and Constitution. March 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Police to Atlantans: If you can, 'stay out of the city'." CNN. March 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ "World's Tallest Buildings". Infoplease. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Craig (1995), p. 15

- ^ "Districts and Zones of Atlanta". Emporis.com. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Hyatt Regency Atlanta.

- ^ Southerland, Randy (2004-11-19). "What do Atlanta's big law firms see in Midtown?". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Expert: Peachtree Poised to Be Next Great Shopping Street". Midtown Alliance. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Mayor to Retailers: Peachtree Is Open for Business". Midtown Alliance. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Total Parkland per 1,000 Residents, by City" (PDF). Center For City Park Excellence. 2006-06-19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2007-06-28 suggested (help) - ^ "Introduction to Atlanta". Frommer's. Wiley Publishing, Inc. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Warhop, Bill. "City Observed: Power Plants". Atlanta. Atlanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "About Us". Trees Atlanta. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Previous Editions". Atlantaintownpaper.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Guerrero, Lucio (2001-03-13). "Lake Forest No. 3 on list of best homes for rich". Chicago Sun-Times online edition. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Overseas Visitation Estimates for U.S. States, Cities, and Census Regions: 2007, retrieved on 2009-11-13.

- ^ America's 30 Most Visited Cities - ForbesTraveler.com, retrieved on 2009-11-13.

- ^ "Big window to the sea". CNN. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ "Park History". Piedmont Park Conservancy. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Stewart, Bruce E. (2004-05-14). "Stone Mountain". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ www.independentfilmmonth.com

- ^ www.outonfilm.org

- ^ "Atlanta, Ga". Information Please Database. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

- ^ "Top 15 Reporting Religious Bodies: Atlanta, GA". Glenmary Research Center. 2002-10-24. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Nelson, Andrew (2009-01-01). "Parishes Receive Data As Catholic Population Surges". The Georgia Bulletin. The Catholic Archdiosese of Atlanta. p. 10.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Business to Business Magazine: Not just for Sunday anymore". Btobmagazine.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Atlanta Statistics". Archatl.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Nelson, Andrew (2007-09-06). "Catholic Population Officially Leaps To 650,000". The Georgia Bulletin. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ These include St. John Chrysostom Melkite Catholic Church; St. Joseph Maronite Catholic Church in the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Brooklyn; and Epiphany Byzantine Catholic Church.

- ^ "The Episcopal Church in Georgia". The Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "About The Salvation Army". The Salvation Army. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ Goodman, Brenda (July 5, 2007). "In a Suburb of Atlanta, a Temple Stops Traffic". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ "Community". Alfarooqmasjid.org. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ a b "Jewish Community Centennial Study 2006". Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "The Story of the Braves." Atlanta Braves. Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "History: Atlanta Falcons." Atlanta Falcons. Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "A Franchise Rich With Tradition: From Pettit To 'Pistol Pete' To The 'Human Highlight Film'." Atlanta Hawks. Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "The WNBA Is Coming to Atlanta in 2008". WNBA.com. WNBA Enterprises, LLC. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "History." Atlanta Thrashers. Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ Falkoff, Robert (2007-11-16). "Commissioner outlines league goals". Major League Soccer, L.L.C. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Before the 2007 season, this was the last event of the PGA Tour season. However, a revamping of the Tour calendar in 2007 created a season-long points race known as the FedEx Cup to determine the Tour's season champion. The Tour Championship, now held in late September, is the final event in the FedEx Cup, although the Tour season continues into November with the Fall Series.

- ^ "Bobby Dodd Stadium At Historic Grant Field :: A Cornerstone of College Football for Nearly a Century". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ "Georgia And Auburn Face Off In Deep South's Oldest Rivalry." georgiadogs.com. November 6, 2006. Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "Peachtree race director deflects praise to others". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Ladies Gaelic Football Na Fianna Atlanta, retrieved on 2009-11-12.

- ^ "Nielsen Reports 1.3% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2007–2008 Season." Nielsen Media Research. (September 22, 2007) Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "About Cox". Cox Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2008". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. GaWC Loughborough University. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ^ "Cities with 5 or more FORTUNE 500 headquarters". CNNMoney.com. 2009-04-08. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "About Wireless Services from AT&T, Formerly Cingular". AT&T Knowledge Ventures. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Woods, Walter (2006-10-17). "Rubbermaid building new HQ, adding 350 jobs". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on 2006-11-13. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ NCR move a burst of good news amid recession, retrieved on 2009-11-13.

- ^ First Data moving HQ to Atlanta - Denver Business Journal, retrieved on 2019-04-09.

- ^ "AeA ranks Atlanta 10th-largest U.S. cybercity". Bizjournals.com. 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Atlanta's top employers, 2006" (PDF). Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ Allen, Frederick (1996). Atlanta Rising. Atlanta, Georgia: Longstreet Press. ISBN 1-56352-296-9.

- ^ "The Largest Banks in the U.S." (chart). The New York Job Source. 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Sarath, Patrice. "SunTrust Banks, Inc". Hoovers. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Bowers, Paige (2001-12-07). "Beers built marble monument for Fed. Reserve". Atlanta Business Chronicle. American City Business Journals, Inc. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ Rauch, Joe (2006-08-21). "Wachovia to put headquarters of card subsidiary in Atlanta". Birmingham Business Journal. American City Business Journals, Inc. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Atlanta: gateway to the future". Hemisphere, Inc. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ McGirt, Dan (2010-01-11). "Plans for the 2009 BIO International Convention in Atlanta, Georgia". BIOtechNOW. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ Duffy, Kevin (2007-08-09). "Supplier to build at Kia site in West Point". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Cox Enterprises, Inc. Reaches Agreement to Acquire Public Minority Stake in Cox Communications, Inc." Cox Enterprises. October 19, 2004. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "City Council Districts." City of Sandy Springs. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "Atlanta Headquarters." Cox Communications. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

- ^ "About Cox". Cox Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Atlanta City Councilman H Lamar Willis". H Lamar Willis. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Lawrence Kestenbaum. "Mayors of Atlanta, Georgia". The Political Graveyard. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ Josh Fecht and Andrew Stevens (2007-11-14). "Shirley Franklin: Mayor of Atlanta". City Mayors. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Atlanta's former mayor sentenced to prison". CNN online. CNN. June 13, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Post Office Location - ATLANTA." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 5, 2009.

- ^ "Atlanta's violent crime at lowest level since '69". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Sugg, John. "Crime is up and the Mayor is out". Creative Loafing. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ^ "Table 4 - Colorado through Idaho". Fbi.gov. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Atlanta, Georgia US Census Bureau

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "Atlanta city, Georgia - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006-2008". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Gurwitt, Rob (2008-07-01). "Governing Magazine: Atlanta and the Urban Future, July 2008". Governing.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "The Seattle Times: 12.9% in Seattle are gay or bisexual, second only to S.F., study says". Seattletimes.nwsource.com. 2006-11-15. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Gary J. Gates Template:PDFlink. The Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law and Public Policy, UCLA School of Law October, 2006.

- ^ http://www.census.gov/statab/ccdb/cit3060r.txt

- ^ "Estimated Daytime Population". U.S. Census Bureau. December 6, 2005. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ "US Census Press Releases". Census.gov. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ Lightsey, Ed (January 2007). "Trend Radar January 2007". Georgia Trend Online. Georgia Trend. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "2007–2008 APS Fast Facts" (PDF). Atlanta Public Schools. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ Tharpe, Jim (2007-01-04). "Atlanta airport still the "busiest": Hartsfield-Jackson nips Chicago's O'hare for second year in a row". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on 2007-01-06. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Delta Invites Customers to Improve Their Handicap with New Service to Hilton Head, Expanded Service to Myrtle Beach". News.delta.com. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "AirTran spreading its wings in Atlanta as Delta refocuses - Atlanta Business Chronicle:". Atlanta.bizjournals.com. 2009-08-28. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Atlanta: Smart Travel Tips". Fodor's. Fodor's Travel. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Atlanta, I-75 at I-85". Worst City Choke Points. Forbes.com. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ "Atlanta Road Lingo". AJC Online. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2006-05-05.

- ^ Copeland, Larry (2001-01-31). "Atlanta pollution going nowhere". USA TODAY. Gannett Co. Inc. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ "Atlanta traffic the worst in America".

- ^ American Public Transportation Association, Heavy Rail Transit Ridership Report, Fourth Quarter 2007.

- ^ Bennett, D.L. (2000-06-16). "Atlanta the Second Most Dangerous City in America for Pedestrians". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Perimeter Transportation Coalition. Retrieved 2007-09-28.