Asylum in the United States

| United States citizenship and immigration |

|---|

| Immigration |

| Citizenship |

| Agencies |

| Legislation |

| History |

| Relevant legislation |

|

|

The United States recognizes the right of asylum for individuals seeking protections from persecution, as specified by international and federal law. People who seek protection while outside the U.S. are termed refugees, while people who seek protection from inside the U.S. are termed asylum seekers. Those who are granted asylum are termed asylees.

A specified number of legally defined refugees who are granted refugee status outside the United States are annually admitted under 8 U.S.C. § 1157 for firm resettlement.[1][2] Other people enter the United States with or without inspection, and apply for asylum under section 1158.[3]

Asylum in the United States has two specific requirements. First, asylum applicants must be physically present in the United States, or at a designated port of arrival.[4] Second, they must show that they suffered persecution in the past, or have a well-founded fear of future persecution in their country of nationality and permanent residency[5] on account of at least one of the five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.[3][6]

Even if an individual meets the criteria for asylum, INA § 208, bars some asylum seekers from asylum. These restrictions fall into two categories: (1) limitations on the ability to apply for asylum and (2) limitations on the ability to be granted asylum.[7][8]

The majority of asylum claims in the United States fail or are rejected.[9] While asylum denial rates had grown to a peak of 71 percent in FY 2020, they fell to 63 percent in FY 2021.[10] One third of asylum seekers go to courts unrepresented although those with legal representation have higher chances of winning.[11]

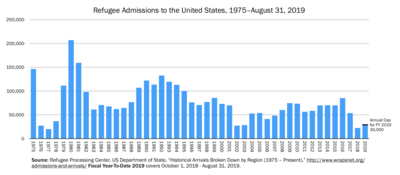

More than three million refugees from various countries around the world have been admitted to the United States since 1980.[12][2] In recent years, the number of refugees admitted by the U.S. has fluctuated due to changes in government policies. For example, the U.S. resettled 84,995 refugees in the fiscal year 2016.[13] The number of refugees admitted declined significantly, with only 11,814 admitted in the fiscal year 2020.[14] The Biden administration aims to increase the number of refugees accepted by setting higher caps for admissions.[15] In 2024 the Biden Administration maintained the 125,000 person cap on refugee admissions.[16]

History

[edit]Character of refugee inflows and resettlement

[edit]

During the Cold War, and up until the mid-1990s, the majority of refugees resettled in the U.S. were people from the former-Soviet Union and Southeast Asia.[17] The most conspicuous of the latter were the refugees from Vietnam following the Vietnam War, sometimes known as "boat people". Following the end of the Cold War, the largest resettled European group were refugees from the Balkans, primarily Serbs, from Kosovo, Bosnia and Croatia.[17] In the 1990s and 2000s, the proportion of Africans rose in the annual resettled population, as many people fled various ongoing conflicts.[17]

Large metropolitan areas have been the destination of most resettlements, with 72% of all resettlements between 1983 and 2004 going to 30 locations.[18] The historical gateways for resettled refugees have been California (specifically Los Angeles, Orange County, San Jose, and Sacramento), the Mid-Atlantic region (New York in particular), the Midwest (specifically Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis–Saint Paul), and Northeast (Providence, Rhode Island).[18] In the last decades of the twentieth century, Northern Virginia; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; and Atlanta, Georgia provided new gateways for resettled refugees. Particular cities are also identified with some national groups: metropolitan Los Angeles received almost half of the resettled refugees from Iran, 20% of Iraqi refugees went to Detroit, and nearly one-third of refugees from the former Soviet Union were resettled in and around New York City.[18]

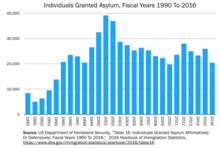

Between 2004 and 2007, nearly 4,000 Venezuelans claimed political asylum in the United States and almost 50% of them were granted. In comparison, in 1996, 328 Venezuelans claimed asylum and 20% of them were granted.[19] According to USA Today, the number of asylums being granted to Venezuelan claimants has risen from 393 in 2009 to 969 in 2012.[20] Other sources confirmed that between 2000 and 2010 the United States granted asylum to 4,500 immigrants from Venezuela.[21]

Sanctuary Movement

[edit]As a pushback to hostile migration policies, many religious groups came together in the 1980s to provide safety for Central American migrants seeking refuge from civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. The movement, tied to the right of asylum that has been built into Western law since Ancient Greece and was built into the Christian faith{{citation needed}}. While this started as a religious movement meant mainly to protect refugees in need, it became quickly politicized, with many sanctuary movement leaders facing trial for going against the law.[22] Sanctuaries have since played an important role in providing legal access and preventing deportation for asylum seekers, especially under the Trump administration.[23]

Relevant law and procedures

[edit]"Under the [INA], the Attorney General may grant asylum to individuals who meet several statutory requirements, including that they have suffered or fear (1) 'persecution,' (2) 'on account of,' (3) their 'race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.'"[6][3] The United States framework on migration is securitization, focusing on the safety of citizens.[24] This results in strict U.S. policies and laws surrounding immigration and asylum.

The United States is obliged to recognize valid claims for asylum under the United Nations' 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.[25] As defined by these agreements, a refugee is a person who is outside their country of nationality (or place of habitual residence if stateless) who, owing to a fear of persecution on account of a protected ground, is unable or unwilling to avail himself of the protection of the state. Protected grounds include race, nationality, religion, political opinion and membership of a particular social group. The signatories to these agreements are further obliged not to return or "refoul" refugees to countries or places where they would face persecution.[25]

This commitment was codified and expanded by the United States Congress with the passing of the Refugee Act of 1980.[26] Besides reiterating the definitions of the 1951 Convention and its Protocol, the Refugee Act provided for the establishment of an Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to help refugees begin their lives in the U.S. The structure and procedures evolved and by 2004, federal handling of refugee affairs was led by PRM,[27] working with the ORR at HHS. Asylum claims are mainly the responsibility of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Refugee quotas

[edit]Each year, the President of the United States sends a proposal to the Congress for the maximum number of refugees to be admitted for the upcoming fiscal year, as specified under INA section 207(e).[1][2] This number, known as the "refugee ceiling", is the target of annual lobbying by both refugee advocates seeking to raise it and anti-immigration groups seeking to lower it. However, once proposed, the ceiling is normally accepted without substantial Congressional debate and does not require Congressional approval. The September 11, 2001 attacks resulted in a substantial disruption to the processing of resettlement claims with actual admissions falling to about 26,000 in fiscal year 2002. Claims were double-checked for any suspicious activity and procedures were put in place to detect any possible terrorist infiltration. Nonetheless, some advocates noted that, given the ease with which foreigners can otherwise legally enter the country, entry as a refugee is comparatively unlikely. The actual number of admitted refugees rose in subsequent years with refugee ceiling for 2006 at 70,000. Critics note these levels are still among the lowest in 30 years.

| Recent actual, projected and proposed refugee admissions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Africa | % | East Asia | % | Europe | % | Latin America and Caribbean |

% | Near East and South Asia |

% | Unallocated reserve |

Total |

| FY 2012 actual arrivals[28] | 10,608 | 18.21 | 14,366 | 24.67 | 1,129 | 1.94 | 2,078 | 3.57 | 30,057 | 51.61 | - | 58,238 |

| FY 2013 ceiling[28] | 12,000 | 17,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 31,000 | 3,000 | 70,000 | |||||

| FY 2013 actual arrivals[29] | 15,980 | 22.85 | 16,537 | 23.65 | 580 | 0.83 | 4,439 | 6.35 | 32,389 | 46.32 | - | 69,925 |

| FY 2014 ceiling[29] | 15,000 | 14,000 | 1,000 | 5,000 | 33,000 | 2,000 | 70,000 | |||||

| FY 2014 actual arrivals[30] | 17,476 | 24.97 | 14,784 | 21.12 | 959 | 1.37 | 4,318 | 6.17 | 32,450 | 46.36 | - | 69,987 |

| FY 2015 ceiling[30] | 17,000 | 13,000 | 1,000 | 4,000 | 33,000 | 2,000 | 70,000 | |||||

| FY 2015 actual arrivals[31] | 22,472 | 32.13 | 18,469 | 26.41 | 2,363 | 3.38 | 2,050 | 2.93 | 24,579 | 35.14 | - | 69,933 |

| FY 2016 ceiling[31] | 25,000 | 13,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 | 34,000 | 6,000 | 85,000 | |||||

| FY 2016 actual arrivals[32] | 31,625 | 37.21 | 12,518 | 14.73 | 3,957 | 4.65 | 1,340 | 1.57 | 35,555 | 41.83 | - | 84,995 |

| FY 2017 ceiling[33] | 35,000 | 12,000 | 4,000 | 5,000 | 40,000 | 14,000 | 110,000 | |||||

| FY 2017 actual arrivals[34] | 20,232 | 37.66 | 5,173 | 9.63 | 5,205 | 9.69 | 1,688 | 3.14 | 21,418 | 39.87 | - | 53,716 |

| FY 2018 ceiling[35] | 19,000 | 5,000 | 2,000 | 1,500 | 17,500 | - | 45,000 | |||||

| FY 2018 actual arrivals[34] | 10,459 | 46.50 | 3,668 | 16.31 | 3,612 | 16.06 | 955 | 4.25 | 3,797 | 16.88 | - | 22,491 |

| FY 2019 ceiling[36] | 11,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 9,000 | - | 30,000 | |||||

| FY 2019 actual arrivals[37] | 16,366 | 54.55 | 5,030 | 16.77 | 4,994 | 16.65 | 809 | 2.70 | 2,801 | 9.34 | - | 30,000 |

| FY 2020 ceiling[38] | – | – | – | – | – | - | 18,000 | |||||

| FY 2020 actual arrivals[39] | 4,160 | 35.21 | 2,129 | 18.02 | 2,578 | 21.82 | 948 | 8.02 | 1,999 | 16.92 | - | 11,814 |

| FY 2021 ceiling[40] | – | – | – | – | – | - | 62,500 | |||||

| FY 2021 actual arrivals*[41] | 6,219 | 54.50 | 776 | 6.80 | 983 | 8.61 | 400 | 3.50 | 3,033 | 26.58 | - | 11,411 |

| FY 2022 ceiling[42] | – | – | – | – | – | - | 125,000 | |||||

| FY 2022 actual arrivals*[43] | 168 | 41.89 | 8 | 2.0 | 104 | 25.93 | 13 | 3.24 | 108 | 26.93 | - | 401 |

- 2022 data are for October only.

A total of 73,293 persons were admitted to the United States as refugees during 2010. The leading countries of nationality for refugee admissions were Iraq (24.6%), Burma (22.8%), Bhutan (16.9%), Somalia (6.7%), Cuba (6.6%), Iran (4.8%), DR Congo (4.3%), Eritrea (3.5%), Vietnam (1.2%) and Ethiopia (0.9%).

Application for resettlement by refugees abroad

[edit]The majority of applications for resettlement to the United States are made to U.S. embassies in foreign countries and are reviewed by employees of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).[44] In these cases, refugee status has normally already been reviewed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and recognized by the host country. For these refugees, the U.S. has stated its preferred order of solutions are: (1) repatriation of refugees to their country of origin, (2) integration of the refugees into their country of asylum and, last, (3) resettlement to a third country, such as the U.S., when the first two options are not viable.[45][46]

The United States prioritizes valid applications for resettlement into 3 levels.[44]

Priority One

[edit]- Persons facing compelling security concerns in countries of first asylum; persons in need of legal protection because of the danger of refoulement; those in danger due to threats of armed attack in an area where they are located; or persons who have experienced recent persecution because of their political, religious, or human rights activities (prisoners of conscience); women-at-risk; victims of torture or violence, physically or mentally disabled persons; persons in urgent need of medical treatment not available in the first asylum country; and persons for whom other durable solutions are not feasible and whose status in the place of asylum does not present a satisfactory long-term solution. – UNHCR Resettlement Handbook[47]

Priority Two

[edit]This is composed of groups designated by the U.S. government as being of special concern. These are often identified by an act proposed by a Congressional representative. Priority Two groups proposed for 2008 included:[48]

- "Jews, Evangelical Christians, and Ukrainian Catholic and Orthodox religious activists in the former Soviet Union, with close family in the United States" (This is the amendment which was proposed by Senator Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J. and originally enacted November 21, 1989.[49][50]

- from Cuba: "human rights activists, members of persecuted religious minorities, former political prisoners, forced-labor conscripts (1965-68), persons deprived of their professional credentials or subjected to other disproportionately harsh or discriminatory treatment resulting from their perceived or actual political or religious beliefs or activities, and persons who have experienced or fear harm because of their relationship – family or social – to someone who falls under one of the preceding categories"[51]

- from Vietnam: "the remaining active cases eligible under the former Orderly Departure Program (ODP) and Resettlement Opportunity for Vietnamese Returnees (ROVR) programs"; individuals who, through no fault of their own, were unable to access the ODP program before its cutoff date; and Amerasian citizens, who are counted as refugee admissions[51]

- individuals who have fled Burma and who are registered in nine refugee camps along the Thai/Burma border and who are identified by UNHCR as in need of resettlement[51]

- UNHCR-identified Burundian refugees who originally fled Burundi in 1972 and who have no possibility either to settle permanently in Tanzania or return to Burundi[51]

- Bhutanese refugees in Nepal registered by UNHCR in the recent census and identified as in need of resettlement

As of August 2021, certain vulnerable groups from Afghanistan are eligible due to the 2021 Taliban offensive.[44]

Priority Three

[edit]This is for cases of family reunification, in which a refugee abroad is brought to the United States to be reunited with a close family member who also has refugee status.[44] A list of nationalities eligible for Priority Three consideration is developed annually. The proposed countries for FY2008 were Afghanistan, Burma, Burundi, Colombia, Congo (Brazzaville), Cuba, Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan and Uzbekistan.[48]

Individual application

[edit]The minority of applications made by individuals who have already entered the U.S. is judged on whether the applicant meets the U.S. definition of "refugee" and on various other statutory criteria (including a number of bars that would prevent an otherwise-eligible refugee from receiving protection). There are two ways to apply for asylum while in the United States:

- If an asylum seeker has been placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge with the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which is a part of the Department of Justice, the individual may apply for asylum with the Immigration Judge. This type of application is regarded as defensive asylum. In this scenario, individuals assert their asylum claims as a defense against deportation. They appear before immigration courts and present their case defensively, often with the assistance of legal counsel, to argue why they should be granted asylum and allowed to remain in the country.

- If an asylum seeker is inside the United States and has not been placed in removal proceedings, he or she may file an application with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), regardless of legal status in the United States. However, if the asylum seeker is not in valid immigration status and USCIS does not grant the asylum application, USCIS may place the applicant in removal proceedings, in that case a judge will consider the application anew. The immigration judge may also consider the applicant for relief that the asylum office has no jurisdiction to grant, such as withholding of removal and protection under the United Nations Convention against Torture. Since the effective date of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), an applicant must apply for asylum within one year of entry or be barred from doing so unless the applicant can establish changed circumstances that are material to their eligibility for asylum or exceptional circumstances related to the delay. This type of asylum application is referred to as Affirmative asylum, which occurs when an individual proactively applies for asylum upon entering or residing in a country, typically through designated government agencies or immigration authorities. Applicants must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. They present their case affirmatively, providing evidence and testimony to support their claim.

- While both pathways ultimately seek the same outcome — protection from persecution — the key difference lies in the timing and context of the asylum claim. Affirmative asylum involves a proactive application process, while defensive asylum arises in response to deportation or removal proceedings. These pathways reflect the diverse circumstances under which individuals seek asylum and navigate complex legal systems in pursuit of safety and security.

Immigration clinics often find it easier to support clients seeking affirmative asylum rather than defensive asylum due to several key factors. Firstly, in affirmative asylum cases, individuals apply for asylum before they face deportation proceedings. This approach allows immigration clinics to prepare a case with time for gathering evidence, conducting interviews, and building a strong defense strategy.

Overall, the proactive nature, greater control over evidence, and less adversarial legal environment make it generally easier for immigration clinics to assist clients seeking affirmative asylum compared to defensive asylum. This underscores the importance of early intervention and comprehensive legal support in asylum-seeking processes.

Immigrants who were picked up after entering the country between entry points can be released by the ICE on payment of a bond, which may lowered or waived by an immigration judge. In contrast, refugees who asked for asylum at an official point of entry before entering the U.S. cannot be released on bond. Instead, ICE officials have full discretion to decide whether they can be released.[52]

If applicants are eligible for asylum, they have a procedural right to have the Attorney General make a discretionary determination as to whether they should be admitted into the United States as asylees. An applicant is also entitled to mandatory "withholding of removal" (or restriction on removal) if the applicant can prove that his or her life or freedom would be threatened upon return to her country of origin. The dispute in asylum cases litigated before the Executive Office for Immigration Review and, subsequently, the federal courts centers on whether the immigration courts properly rejected the applicant's claim that she or he is eligible for asylum or other relief.

Applicants have the burden of proving that they are eligible for asylum. To satisfy this burden, they must show that they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country on account of either race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.[53] The applicant can demonstrate well-founded fear by demonstrating that he or she has a subjective fear (or apprehension) of future persecution in her home country that is objectively reasonable. An applicant's claim for asylum is stronger where they can show past persecution, in which case they will receive a presumption that they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. The government can rebut this presumption by demonstrating either that the applicant can relocate to another area within their home country in order to avoid persecution, or that conditions in the applicant's home country have changed such that the applicant's fear of persecution there is no longer objectively reasonable. Technically, an asylum applicant who has suffered past persecution meets the statutory criteria to receive a grant of asylum even if the applicant does not fear future persecution. In practice, adjudicators will typically deny asylum status in the exercise of discretion in such cases, except where the past persecution was so severe as to warrant a humanitarian grant of asylum, or where the applicant would face other serious harm if returned to their country of origin. In addition, applicants who, according to the US Government, participated in the persecution of others are not eligible for asylum.[54]

A person may face persecution in their home country because of race, nationality, religion, ethnicity, or social group, and yet not be eligible for asylum because of certain bars defined by law. The most frequent bar is the one-year filing deadline. If an application is not submitted within one year following the applicant's arrival in the United States, the applicant is barred from obtaining asylum unless certain exceptions apply. However, the applicant can be eligible for other forms of relief such as Withholding of Removal, which is a less favorable type of relief than asylum because it does not lead to a Green Card or citizenship. The deadline for submitting the application is not the only restriction that bars one from obtaining asylum. If an applicant persecuted others, committed a serious crime, or represents a risk to U.S. security, he or she will be barred from receiving asylum as well.[55] After 2001, asylum officers and immigration judges became less likely to grant asylum to applicants, presumably because of the attacks on 11 September.[56]

In 1986 an Immigration Judge agreed not to send Fidel Armando-Alfanso back to Cuba, based on his membership in a particular social group (LGBTQ+ individuals) who were persecuted and feared further persecution by the government of Cuba.[57] The Board of Immigration Appeals upheld the decision in 1990, and in 1994, then-Attorney General Janet Reno ordered this decision to be a legal precedent binding on Immigration Judges and the Asylum Office, and established sexual orientation as a grounds for asylum.[57][58] However, in 2002 the Board of Immigration Appeals "suggested in an ambiguous and internally inconsistent decision that the ‘protected characteristic’ and ‘social visibility’ tests may represent dual requirements in all social group cases."[59][60] The requirement for social visibility means that the government of a country from which the person seeking asylum is fleeing must recognize their social group, and that LGBT people who hide their sexual orientation, for example out of fear of persecution, may not be eligible for asylum under this mandate.[60]

In 1996 Fauziya Kasinga, a 19-year-old woman from the Tchamba-Kunsuntu people of Togo, became the first person to be granted asylum in the United States to escape female genital mutilation. In August 2014, the Board of Immigration Appeals, the United States's highest immigration court, found for the first time that women who are victims of severe domestic violence in their home countries can be eligible for asylum in the United States.[61] However, that ruling was in the case of a woman from Guatemala and was anticipated to only apply to women from there.[61] On June 11, 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed that precedent and announced that victims of domestic abuse or gang violence will no longer qualify for asylum.[62]

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca

[edit]The term "well-founded fear" has no precise definition in asylum law. In INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987), the Supreme Court avoided attaching a consistent definition to the term, preferring instead to allow the meaning to evolve through case-by-case determinations. However, in Cardoza-Fonseca, the Court did establish that a "well-founded" fear is something less than a "clear probability" that the applicant will suffer persecution. Three years earlier, in INS v. Stevic, 467 U.S. 407 (1984), the Court held that the clear probability standard applies in proceedings seeking withholding of deportation (now officially referred to as 'withholding of removal' or 'restriction on removal'), because in such cases the Attorney General must allow the applicant to remain in the United States. With respect to asylum, because Congress employed different language in the asylum statute and incorporated the refugee definition from the international Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the Court in Cardoza-Fonseca reasoned that the standard for showing a well-founded fear of persecution must necessarily be lower.

An applicant initially presents his claim to an asylum officer, who may either grant asylum or refer the application to an Immigration Judge. If the asylum officer refers the application and the applicant is not legally authorized to remain in the United States, the applicant is placed in removal proceedings. After a hearing, an immigration judge determines whether the applicant is eligible for asylum. The immigration judge's decision is subject to review on two, and possibly three, levels. First, the immigration judge's decision can be appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals. In 2002, in order to eliminate the backlog of appeals from immigration judges, the Attorney General streamlined review procedures at the Board of Immigration Appeals. One member of the Board can affirm a decision of an immigration judge without oral argument; traditional review by three-judge panels is restricted to limited categories for which "searching appellate review" is appropriate. If the BIA affirms the decision of the immigration court, then the next level of review is a petition for review in the United States courts of appeals for the circuit in which the immigration judge sits. The court of appeals reviews the case to determine if "substantial evidence" supports the immigration judge's (or the BIA's) decision. As the Supreme Court held in INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12 (2002), if the federal appeals court determines that substantial evidence does not support the immigration judge's decision, it must remand the case to the BIA for further proceedings instead of deciding the unresolved legal issue in the first instance. Finally, an applicant aggrieved by a decision of the federal appeals court can petition the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case by a discretionary writ of certiorari. But the Supreme Court has no duty to review an immigration case, and so many applicants for asylum forego this final step.

Notwithstanding his statutory eligibility, an applicant for asylum will be deemed ineligible if:

- the applicant participated in persecuting any other person on account of that other person's race, religion, national origin, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the community because he has been convicted in the United States of a particularly serious crime;

- the applicant has committed a serious non-political crime outside the United States prior to arrival;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the security of the United States;

- the applicant is inadmissible on terrorism-related grounds;

- the applicant has been firmly resettled in another country prior to arriving in the United States; or

- the applicant has been convicted of an aggravated felony as defined more broadly in the immigration context.

Conversely, even if an applicant is eligible for asylum, the Attorney General may decline to extend that protection to the applicant. (The Attorney General does not have this discretion if the applicant has also been granted withholding of deportation.) Frequently the Attorney General will decline to extend an applicant the protection of asylum if he has abused or circumvented the legal procedures for entering the United States and making an asylum claim.

Work permit and permanent residence status

[edit]An in-country applicant for asylum is eligible for a work permit (employment authorization) after their application for asylum has been pending for 365 days.[63] If an asylum seeker is recognized as a refugee, he or she may apply for lawful permanent residence status (a green card) one year after being granted asylum. Asylum seekers generally do not receive economic support. This, combined with a period where the asylum seeker is ineligible for a work permit is unique among developed countries and has been condemned from some organisations, including Human Rights Watch.[64]

Up until 2004, recipients of asylee status faced a wait of approximately fourteen years to receive permanent resident status after receiving their initial status, because of an annual cap of 10,000 green cards for this class of individuals. However, in May 2005, under the terms of a proposed settlement of a class-action lawsuit, Ngwanyia v. Gonzales, brought on behalf of asylees against CIS, the government agreed to make available an additional 31,000 green cards for asylees during the period ending on September 30, 2007. This is in addition to the 10,000 green cards allocated for each year until then and was meant to speed up the green card waiting time considerably for asylees. However, the issue was rendered somewhat moot by the enactment of the Real ID Act of 2005 (Division B of United States Public Law 109-13 (H.R. 1268)), which eliminated the cap on annual asylee green cards. Currently, an asylee who has continuously resided in the US for more than one year in that status has an immediately available visa number.

On April 29, 2019, President Trump ordered new restrictions on asylum seekers at the Mexican border — including application fees and work permit restraints — and directed that cases in the already clogged immigration courts be settled within 180 days.[65]

Detention in the United States

[edit]Once asylum seekers enter the United States they have exactly one year to apply for asylum. During that year asylum seekers are responsible for providing their own legal assistance and representation.[11] Until their cases are approved, and sometimes even after approval and receipt of green cards, asylum seekers are at a constant risk of detention. The ICE has statutory authority to detain any person suspected of violating immigration laws. As of December 2018, 47,486 people were detained for various reasons. Of those 29,753 had no criminal conviction.[66] Detention centers are government-funded facilities modeled after U.S. prisons.[11]

Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program

[edit]An Unaccompanied Refugee Minor (URM) is any person who has not attained 18 years of age who entered the United States unaccompanied by and not destined to: (a) a parent, (b) a close non-parental adult relative who is willing and able to care for said minor, or (c) an adult with a clear and court-verifiable claim to custody of the minor; and who has no parent(s) in the United States.[67] Initially, only unaccompanied refugee children were included under this program, but it was later expanded to include unaccompanied asylees, special immigrant juveniles, Cuban and Haitian entrants, U- and T-status recipients, and Afghan and Ukrainian parolees.

The URM program is coordinated by the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), a branch of the United States Administration for Children and Families. The mission of the URM program is to help people in need "develop appropriate skills to enter adulthood and to achieve social self-sufficiency." To do this, URM provides minors under the program with the same social services available to U.S.-born children, including, but not limited to, housing, food, clothing, medical care, educational support, counseling, and support for social integration.[68]

Government support after arrival

[edit]The United States does not fund legal representation for asylum seekers, but it does offer funding to aid the first 120 days of resettlement for people granted asylum. The Office of Refugee Resettlement provides funding to volags that are then responsible to aid asylees in becoming economically independent.[69] These organizations help asylees find housing, get work permits, apply for social security cards, enroll in ESL classes, apply for Medicaid and find jobs.[69] Many refugees depend on public benefits at first, but the goal is that over time they become self-sufficient.[70] Availability of public assistance programs can vary depending on which states within the United States refugees are allocated to resettle in. In 2016, The American Journal of Public Health reported that only 60% of refugees are assigned to resettlement locations with expanding Medicaid programs, meaning that more than 1 in 3 refugees may have limited healthcare access.[71] Immediately after being granted asylum people are able to apply for their immediate families to receive asylum.[72] After one full year of protection in the United States asylees are able to apply for green cards, and four years later, for citizenship.[72]

Child separation

[edit]The recent U.S. Government policy known as "Zero-tolerance" was implemented from April to June 2018.[73] In response, a number of scientific organizations released statements on the negative impact of child separation, a form of childhood trauma, on child development, including the American Psychiatric Association,[74] the American Psychological Association,[75] the American Academy of Pediatrics,[76] the American Medical Association,[77] and the Society for Research in Child Development.[78]

According to a study conducted by Joanna Dreby, trauma associated with family separation can have significant effects on the mental and physical well-being of children. Dreby's study concluded that academic difficulties and mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression are prevalent among children whose families have been separated during migration.[79]

Efforts are underway to minimize the impact of child separation. For instance, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network released a resource guide and held a webinar related to traumatic separation and refugee and immigrant trauma.

Obstacles faced by asylum seekers

[edit]Backlogs

[edit]There are 600 immigration judges.[80] The immigration courts had a backlog of 394,000 asylum cases in January 2021, and 470,000 in March 2022,[81] although another source says the backlog in November 2021 was 672,000, with an average wait of 1,942 days (5 1/3 years).[82] The overall immigration court backlog was 1.9 million in August 2022, with an average wait of 798 days (2.2 years).[83]

At the US Customs and Immigration Service, the backlog was 3 million immigration applications pending in 2013, rising to 5.7 million in September 2019 and 9.5 million in February 2022.[84]

LGBTQ asylum seekers

[edit]Historically, homosexuality was considered a deviant behavior in the US; as such, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 barred homosexual individuals from entering the United States due to concerns about their psychological health.[85] One of the first successful LGBT asylum pleas to be granted refugee status in the United States due to sexual orientation was a Cuban national whose case was first presented in 1989.[86] The case was affirmed by the Board of Immigration Appeals and the barring of LGBT individuals into the United States was repealed in 1990. The case, known as Matter of Acosta (1985), set the standard of what qualified as a "particular social group." This new definition of "social group" expanded to explicitly include homosexuality and the LGBT population. It considers homosexuality and gender identity a "common characteristic of the group either cannot change or should not be required to change because it is fundamental to their individual identities or consciences."[87] The definition was intended to be open-ended in order to fit with the changing understanding of sexuality. This allows political asylum to some LGBT individuals who face potential criminal penalties due to homosexuality and sodomy being illegal in the home country who are unable to seek protection from the state.[88][89]

Susan Berger argues that while homosexuality and other sexual minorities might be protected under the law, the burden of proving that they are an LGBT member demonstrates a greater immutable view of the expected LGBT performance.[90] The importance of visibility is stressed throughout the asylum process, as sexuality is an internal characteristic. It is not visibly represented in the outside appearance.[91] According to Amanda M. Gómez, sexual orientation identity is formed and performed in the asylum process.[92] Unlike race or gender, in sexual orientation asylum claims, applicants have to prove their sexuality to convince asylum officials that they are truly part of their social group.[92] Rachel Lewis and Nancy Naples argue that LGBT people may not seem credible if they do not fit Western stereotypes of what LGBT people look like[93]. Dress, mannerisms, and style of speech, as well as not having had public romantic relationships with the opposite sex, may be perceived by the immigration judge as not reflective of the applicants’ sexual orientation.[94] Scholars and legal experts have long argued that asylum law has created legal definitions for homosexuality that limit our understanding of queerness.[92]

Human Rights and LGBT advocates have worked to create many improvements to the LGBT Asylum Seekers coming into the United States and to give asylum seekers a chance to start a new life.[95] A 2015 report issued by the LGBT Freedom and Asylum network identifies best practices for supporting LGBT asylum seekers in the US.[96] The US State Department has also issued a factsheet on protecting LGBT refugees.[97]

Gender

[edit]Female asylum seekers may encounter issues when seeking asylum in the United States due to what some see as a structural preference for male narrative forms in the requirements for acceptance.[90] Researchers, such as Amy Shuman and Carol Bohmer, argue that the asylum process produces gendered cultural silences, particular in hearings where the majority of narrative construction takes place.[98] Cultural silences refers to things that women refrain from sharing, due to shame, humiliation, and other deterrents.[98] These deterrents can make achieving asylum more difficult as it can keep relevant information from being shared with the asylum judge.[98]

These experiences are articulated during the hearing process where the responsibility to prove membership is on the applicant.[90][98][87] During the hearing process, applicants are encouraged to demonstrate persecution for gender or sexuality and place the source as their own culture. Shuman and Bohmer argue that in sexual minorities, it is not enough to demonstrate only violence, asylum applicants have to align themselves against a restrictive culture. The narratives are forced to fit into categories shaped by western culture or else they are found to be fraudulent.[98]

Susan Berger argues that the relationship between gender and sexuality leads to arbitrary case decisions, as there are no clear guidelines for when the private problems becomes an international problem. According to Shuman and Bohmer, due to women's social position in most countries, lesbians are more likely to stay in the closet, which often means that they do not have the public visibility element that the asylum process requires for credibility.[98] This leads to Lewis and Naples’ critique to the fact that asylum officials often assume that since women do not live such public lives as men do, that they would be safe from abuse or persecution, in comparison to gay men who are often part of the public sphere.[93] This argument violates the concept that one's sexual orientation is a fundamental right and that family and the private sphere are often the first spaces where lesbians experience violence and discrimination.[93] Because lesbians live such hidden lives, they tend to lack police reports, hospital records, and letters of support from witnesses, which decreases their chances of being considered credible and raises the stakes of effectively telling their stories in front of asylum officials.[93]

Transgender individuals have a higher risk for mental health problems when compared to cisgender counterparts. Many transgender individuals face socioeconomic difficulties in addition to being an asylum seeker. In a study conducted by Mary Gowin et al. of Mexican Transgender Asylum Seekers, they found 5 major stressors among the participants including assault (verbal, physical and sexual), "unstable environments, fear for safety and security, hiding undocumented status, and economic insecurity."[99] They also found that all of the asylum seekers who participated reported at least one health issue that could be attributed to the stressors. Participants accessed little or no use of health or social services, attributed to barriers to access, such as fear of the government, language barriers and transportation.[99] They are also more likely to report lower levels of education due to few opportunities after entering the United States. Many of the asylum seeker participants entered the United States as undocumented immigrants. Obstacles to legal services included fear and knowledge that there were legal resources to gaining asylum.[99]

Gang violence

[edit]In 2018, Attorney General Sessions issued a decision in Matter of A-B- that precluded people fleeing gang violence from qualifying for asylum protections based on that alone. In 2021, Attorney General Garland vacated Matter of A-B-, which allows the possibility of asylum seekers to prevail on such claims.[100][6] Indiscriminate gang violence does not fit under the claim of persecution based on social group.[101] The rationale is that gangs do not target people based on their social group but rather anyone in their territory. Many people in the Northern Triangle of Central America flee their homes in search of safety from members of gangs.[101]

Climate change

[edit]Climate change and natural disasters have caused 265 million people to migrate since 2008.[102] People who have been forced out of their homes and ways of life due to climate change are not recognized and protected under United States asylum policy because they do not fit under one of the protected categories of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership of a particular social group.[102] There are not any protections for environmental refugees on the national, or even international, level.[103] While their homes and villages may be destroyed due to earthquakes, hurricanes, rising sea water etc., the U.S. does not provide them protection. An October 2021 report from The White House titled "The Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration" stresses the need and development for further humanitarian assistance in disasters of climate change.[104]

Technology

[edit]The integration of digital tools and artificial intelligence in the U.S. asylum process has the potential to improve efficiency and accessibility for asylum seekers, but it also exacerbates existing inequalities, raises significant privacy concerns, and risks perpetuating biases in decision-making. While technological advancements, such as mobile applications, online case management systems, and AI-driven analytics, offer new pathways to streamline asylum procedures, the benefits are not equitably distributed due to digital inequality and systemic challenges. For technology to positively impact the asylum process, policymakers must address these disparities, implement rigorous privacy safeguards, and ensure transparency in AI applications to uphold the rights and dignity of asylum seekers.

1. Efficiency and accessibility

[edit]Digital tools like websites and mobile applications can be a promising way to provide information about public benefits to asylum seekers. [105] For example, the CBP One mobile application, used by the U.S. government, allows asylum seekers to schedule appointments to present themselves at a port of entry to the U.S.[106] The application requires asylum seekers to submit personal data, including a facial photograph for facial recognition.[107]

These tools can also facilitate remote registration and interview processes, potentially reducing geographical barriers and wait times.[108] Mobile applications, in particular, can offer asylum seekers a direct channel to schedule appointments with immigration officials and access relevant information about their cases. Additionally, these tools can provide language support, connect asylum seekers with legal resources, and disseminate essential information regarding their rights and procedures.[109]

However, many asylum seekers lack access to reliable internet connections, digital devices, and the necessary digital literacy skills.[110] This disparity creates a barrier for those already marginalized and highlights the need for policymakers to prioritize initiatives that provide equitable access to technology, digital literacy training, and language support.

2. Data privacy

[edit]A key concern with the use of technology in the asylum process is the potential for data privacy violations. The collection, storage, and use of personal information, including biometrics, raise significant concerns about surveillance, profiling, and the potential misuse of sensitive data.[111] This is especially concerning in the context of heightened immigration enforcement. Asylum seekers, already fearful of persecution, may be hesitant to share personal information through digital platforms, further hindering their access to essential resources. One study found that this hesitancy is justified due to the precarity inherent in the immigration system, especially for vulnerable immigrant groups, such as undocumented immigrants. [112] One healthcare professional explained, "If I am undocumented, I’m not going to go to a website and click on a search option that says 'I’m undocumented,' right, because I’d be terrified of who’s taking that information, where’s it going". [113]

It is imperative to implement robust privacy safeguards and data protection measures that prioritize the security and confidentiality of asylum seekers' information.[114] One potential solution is to allow asylum seekers to own electronic files in which they could capture details of their journey and upload evidence supporting their story, giving them control over what data they share.[115]

3. A human-centered approach

[edit]The integration of technology in the asylum process must prioritize upholding the rights and dignity of asylum seekers.[116] Policymakers must proceed with caution, ensuring that technological advancements do not come at the expense of fairness, due process, and the fundamental right to seek asylum. [117] To achieve a just and equitable asylum system, the focus must shift from solely pursuing efficiency to prioritizing human-centered design principles that center the needs and experiences of asylum seekers.

This involves:

- Conducting thorough human rights impact assessments before implementing new technologies.

- Ensuring access to legal counsel and human review of all AI-driven decisions.

- Promoting transparency and accountability in the development and application of algorithms.

- Investing in digital literacy training and language support for asylum seekers.

- Centering the voices and experiences of asylum seekers in the design and implementation of technology.

Only by addressing the ethical considerations and potential harms of technology can its integration truly enhance the asylum process and contribute to a fairer and more humane system for those seeking protection.

Criticism

[edit]Concerns have been raised with the U.S. asylum and refugee determination processes. A 2007 empirical analysis by described the U.S. asylum process as a game of refugee roulette, meaning that the outcome of asylum determinations depends largely on the particular adjudicator to whom an application is randomly assigned, rather than on the merits of the case.[118][119]

In 2008 study of immigration court decision-making between 1994 and 2007, the United States Government Accountability Office similarly found that "the likelihood of being granted asylum varied considerably across and within the [immigration courts studied]."[120] After changes were made the disparities decreased somewhat after 2008.

A substantial amount of research has also emerged about the effects of the asylum process on refugees' mental health. Intense psychological stress caused by asylum interviews often compounds pre-existing trauma for refugees, often with little assistance provided by legal professionals to ease the process.[121] This can make it more difficult for traumatized refugees to meet credibility standards in court, as many individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder struggle with retrieving certain memories in detail, particularly in high stress inducing situations.[122] Legal and medical scholars have begun arguing for the incorporation of mental health professionals into the asylum process as a form of harm reduction.[123]

Certain other policies meant to lower the number of refugees entering the country have also received criticism for their role in creating trauma and for violating asylum seekers' human rights. Detention centers, extremely common in the United States under the Trump administration, are particularly controversial and remain a prominent aspect of US immigration policy.[124] Studies from Australia have proven that detention policies have a long-term negative impact on asylum seekers mental health.[125] Other policies such as forced separations and community dispersions, precise and difficult to meet standards to qualify for asylum, and restricted access to basic needs during the process have also been pointed to as unnecessary and damaging.[126]

The process has also received criticism for playing into a substantial power imbalance between the asylum-seeker and the legal professionals involved in their cases. Issues with translation, especially those created through cultural and linguistic differences, often lead to confusion and disadvantage the asylum seeker. This can be due to a lack of understanding on the refugees' end as to what they are supposed to discuss or a misinterpretation of the refugees' discourse by the legal professional working with them.[127][128]

Film

[edit]The 2001 documentary film Well-Founded Fear, from filmmakers Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini marked the first time that a film crew was privy to the private proceedings at the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), where individual asylum officers ponder the often life-or-death fate of the majority of immigrants seeking asylum. The film analyzes the US asylum application process by following several asylum applicants and asylum officers.

See also

[edit]- Sanctuary city

- Negusie v. Holder (2009)

- Boika v. Holder (2013)

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b "Reznik v. U.S. Department of Justice, INS, 901 F. Supp. 188". U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Harvard Law School. March 28, 1995. p. 193.

Congress granted the President and Attorney General wide discretion in determining the admission of refugees to the United States.

- ^ a b c "Vartelas v. Holder, 566 U.S. 257". U.S. Supreme Court. Harvard Law School. March 28, 2012. p. 262.

Congress made 'admission' the key word, and defined admission to mean 'the lawful entry of the alien into the United States after inspection and authorization by an immigration officer.' § 1101(a)(13)(A).

- ^ a b c INA section 208, 8 U.S.C. § 1158 ("Asylum").

- ^ "Asylum | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. 2022-11-09. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ Rempell, Scott (2011-10-08). "Defining Persecution". Rochester, NY. SSRN 1941006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "Matter of A-B-, 28 I&N Dec. 307". Attorney General. U.S. Dept. of Justice. June 16, 2021.

- ^ "8 USC 1158: Asylum". uscode.house.gov. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ Smith, Hillel (September 7, 2022). "An Overview of the Statutory Bars to Asylum: Limitations on Applying for Asylum" (PDF). Congressional Research Service Legal Sidebar – via CSR Legal Sidebar.

- ^ "Refugees in the United States of America". Worlddata.info. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ "Asylum Grant Rates Climb Under Biden". trac.syr.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ a b c Rabben, Linda 1947- Verfasser. (2016). Sanctuary and asylum : a social and political history. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99912-8. OCLC 964063441.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "U.S. Refugee Admissions Program". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Fiscal Year 2016 Refugee Admissions". Fact Sheet: Fiscal Year 2016 Refugee Admissions. U.S. Department of State, Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ "An Overview of U.S. Refugee Law and Policy". American Immigration Council. 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ "Statement by President Joe Biden on Refugee Admissions". The White House. 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ "Biden administration plans to keep refugee cap at 125,000". CNN. September 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c Igielnik, Ruth; Krogstad, Jens Manuel (3 February 2017). "Where refugees to the U.S. come from". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Audrey Singer and Jill H. (2006-09-01). "From 'There' to 'Here': Refugee Resettlement in Metropolitan America". Brookings. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ "Venezuela-Colombia" (PDF). www.discipleshomemissions.org. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Venezuelan middle class seeks refuge in Miami". USA Today.

- ^ "Thousands of Venezuelans Have Gotten Political Asylum in the U.S." Fox News. 24 June 2011.

- ^ Rabben, Linda 1947- (2016). Sanctuary and asylum : a social and political history. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99912-8. OCLC 964063441.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Haberman, Clyde (2017-03-06). "Trump and the Battle Over Sanctuary in America". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ Refugees and asylum seekers : interdisciplinary and comparative perspectives. Berthold, S. Megan (Sarah Megan), Libal, Kathryn, 1968-, Mollica, Richard F. Santa Barbara, California. 24 June 2019. ISBN 978-1-4408-5496-5. OCLC 1103221731.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "The 1951 Refugee Convention". UNHCR. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ "The Refugee Act". The Office of Refugee Resettlement. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ^ a b "Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2014" (PDF). US Department of State.

- ^ a b "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2015". 2009-2017.state.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ a b "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2016". 2009-2017.state.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ a b "Documents for Congress". 2009-2017.state.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Arrivals by Region 2016_09_30". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 2015-11-06.

- ^ "Presidential Determination -- Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2017". whitehouse.gov. 2016-09-28. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ a b "Refugee Processing Center". Refugee Processing Center. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2018". 2017-10-05. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2019" (PDF). www.state.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Admissions & Arrivals | Arrivals by Region | 2019". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2020". www.politico.com.

- ^ "Admissions & Arrivals | Arrivals by Region | 2020". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021 | The Center". www.thecenterutica.org. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Admissions & Arrivals | Arrivals by Region | 2021". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ "How many refugees will President Biden welcome from Afghanistan and other countries? | International Rescue Committee (IRC)". www.rescue.org. 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Admissions & Arrivals | Arrivals by Region | 2022". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ a b c d "Refugees". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. September 23, 2021. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ "Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2022". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ "The United Nations high commissioner for refugees". 2012-12-31. doi:10.18356/f5abb3a9-en. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Resettlement". UNHCR. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ a b Report to the Congress Submitted on Behalf of The President of The United States to the Committees on the Judiciary United States Senate and United States House of Representatives in Fulfillment of the Requirements of Section 207(E) (1)-(7) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, Released by the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration of the United States Department of State, p. 8

- ^ Foreign Operations, Export Financing, & Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-167, §§ 599D, 599E, 103 Stat. 1195, 1262 (1989) (codified as amended at 8 U.S.C. § 1157) (2000). https://www.congress.gov/101/statute/STATUTE-103/STATUTE-103-Pg1195.pdf

- ^ Rosenberg, Victor (2015) "Refugee Status for Soviet Jewish Immigrants to the United States," Touro Law Review: Vol. 19: No. 2, Article 22. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol19/iss2/22

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Refugee Priorities". HIAS. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ Satija, Neena (2018-07-05). "The Trump administration is not keeping its promises to asylum seekers who come to ports of entry". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ Chang, Ailsa (September 28, 2018). "Thousands Could Be Deported As Government Targets Asylum Mills' Clients". NPR. No. All Things Considered. NPR.

- ^ "Asylum in the United States". kschaeferlaw.com/immigration-overview/asylum. Kimberley Schaefer. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Green Card Through Asylum". us-counsel.com/green-cards/green-card-asylum. Givi Kutidze. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Farris, Christopher J. and Rottman, Andy J. "The Path to Asylum in the US and the Determinants for Who Gets In and Why." International Migration Review, Volume 43, Issue 1, Pages 3-34. First Published March 2, 2009.

- ^ a b "Asylum Based on Sexual Orientation and Fear of Persecution". Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "How Will Ugandan Gay Refugees Be Received By U.S.?". NPR.org. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Marouf, Fatma E. (2008) "The Emerging Importance of "Social Visibility" in Defining a Particular Social Group and Its Potential Impact on Asylum Claims Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender". Scholarly Works. Paper 419, pg. 48

- ^ a b "Social visibility, asylum law, and LGBT asylum seekers". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Preston, Julia (29 August 2014). "In First for Court, Woman Is Ruled Eligible for Asylum in U.S. on Basis of Domestic Abuse". The New York Times. p. A12. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Benner, Katie; Dickerson, Caitlin (11 June 2018). "Sessions Says Domestic and Gang Violence Are Not Grounds for Asylum". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ "Instructions for Application for Employment Authorization" (PDF). USCIS. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (12 November 2013). US: Catch-22 for Asylum Seekers. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Kanno-Youngs, Zolan; Dickerson, Caitlin (2019-04-29). "Asylum Seekers Face New Restraints Under Latest Trump Orders". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- ^ "ICE Focus Shifts Away from Detaining Serious Criminals". trac.syr.edu. Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Congressional Research Service Report to Congress, Unaccompanied Refugee Minors, Policyarchive.org pg. 7

- ^ "About Unaccompanied Refugee Minors". Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2013-11-25.

- ^ a b Nawyn, Stephanie J. (2017-10-18). Faithfully Providing Refuge: The Role of Religious Organizations in Refugee Assistance and Advocacy. eScholarship, University of California. OCLC 1078275108.

- ^ "Ten Facts About U.S. Refugee Resettlement". migrationpolicy.org. 2015-10-21. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Agrawal, Pooja; Venkatesh, Arjun Krishna (2016). "Refugee Resettlement Patterns and State-Level Health Care Insurance Access in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (4): 662–3. doi:10.2105/ajph.2015.303017. PMC 4816078. PMID 26890186.

- ^ a b "Benefits and Responsibilities of Asylees". USCIS. 2018-03-08. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ "Memorandum for Federal Prosecutors Along the Southwest Border, Zero-Tolerance for Offenses Under 8 U.S.C. § 1325(a)".

- ^ "APA Statement Opposing Separation of Children from Parents at the Border". psychiatry.org. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ "Statement of APA President Regarding the Traumatic Effects of Separating Immigrant Families". apa.org. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ "AAP Statement on Executive Order on Family Separation". aap.org. Archived from the original on 2018-07-28. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ "Doctors oppose policy that splits kids from caregivers at border". AMA Wire. 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ "The Science is Clear: Separating Families has Long-term Damaging Psychological and Health Consequences for Children, Families, and Communities". Society for Research in Child Development. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ Dreby, Joanna (2015-05-01). "U.S. immigration policy and family separation: The consequences for children's well-being". Social Science & Medicine. 132: 245–251. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.041. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 25228438.

- ^ "Office of the Chief Immigration Judge". www.justice.gov. 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ Wright, Cora (2022-10-03). "Barriers and Backlog: Asylum Office Delays Continue to Cause Harm". Human Rights First. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Immigration Court Asylum Backlog". Syracuse University. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Immigration Court Backlog Tool: Pending Cases and Length of Wait in Immigration Courts". Syracuse University. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ Gelatt, Julia, and Muzaffar Chishti (2022-02-22). "Mounting Backlogs Undermine U.S. Immigration System and Impede Biden Policy Changes". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shannon, Minter (1993). "Sodomy and Public Morality Offenses under U.S. Immigration Law: Penalizing Lesbian and Gay Identity". Cornell International Law Journal. 26 (3). ISSN 0010-8812.

- ^ "Social visibility, asylum law, and LGBT asylum seekers". Twin Cities Daily Planet. October 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Vogler, Stefan (2016). "Legally Queer: The Construction of Sexuality in LGBQ Asylum Claims". Law & Society Review. 50 (4): 856–889. doi:10.1111/lasr.12239.

- ^ Kerr, Jacob (June 19, 2015). "LGBT Asylum Seekers Not Getting Enough Relief In U.S., Report Finds". Huffington Post.

- ^ Taracena, Maria Inés (May 27, 2014). "LGBT Global Persecution Leads to Asylum Seekers in Southern AZ". Arizona Public Media, NPR.

- ^ a b c Berger, Susan A (2009). "Production and Reproduction of Gender and Sexuality in Legal Discourses of Asylum in the United States". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 34 (3): 659–85. doi:10.1086/593380. S2CID 144293440.

- ^ Marouf, Fatma (2008). "The Emerging Importance of "Social Visibility" in Defining a "Particular Social Group" and Its Potential Impact on Asylum Claims Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender". Yale Law & Policy Review. 27 (1): 47–106.

- ^ a b c Gómez, Amanda (2017). "Tremendo Show: Performing and Producing Queerness in Asylum Claims Based on Sexual Orientation". LGBTQ Policy Journal. 7: 1–8.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Rachel A; Naples, Nancy A (2014-12-01). "Introduction: Queer migration, asylum, and displacement". Sexualities. 17 (8): 911–918. doi:10.1177/1363460714552251. ISSN 1363-4607. S2CID 145064223.

- ^ Crease, Robert P. (2017). "Entry Denied". Physics World. 30 (5): 18. Bibcode:2017PhyW...30e..18C. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/30/5/31.

- ^ Mertus, Julie (2007). "The Rejection of Human Rights Framings: The Case of LGBT Advocacy in the US". Human Rights Quarterly. 29 (4): 1036–64. doi:10.1353/hrq.2007.0045. JSTOR 20072835. S2CID 145297080.

- ^ "Best Practice Guide: Supporting LGBT Asylum Seekers in the United States" (PDF). LGBT Freedom and Asylum Network.

- ^ US Department of State LGBT Human Rights Fact Sheet, US Department of State, accessed May 14, 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Shuman, Amy; Bohmer, Carol (2014). "Gender and cultural silences in the political asylum process". Sexualities. 17 (8): 939–57. doi:10.1177/1363460714552262. S2CID 146743693.

- ^ a b c Gowin, Mary; Taylor, E. Laurette; Dunnington, Jamie; Alshuwaiyer, Ghadah; Cheney, Marshall K (2017). "Needs of a Silent Minority: Mexican Transgender Asylum Seekers". Health Promotion Practice. 18 (3): 332–340. doi:10.1177/1524839917692750. PMID 28187690. S2CID 206740929.

- ^ "Vazquez v. Garland, No. 20-9641" (PDF). U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. Casetext.com. December 8, 2021. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Masetta-Alvarez, Katelyn (2018). Tearing down the Wall between Refuge and Gang-Based Asylum Seekers : Why the United States Should Reconsider Its Stance on Central American Gang-Based Asylum Claims. OCLC 1052550825.

- ^ a b Francis, A (2020). "Climate-Induced Migration & Free Movement Agreements". Journal of International Affairs. 73: 123–133.

- ^ Berthold, S. Megan (Sarah Megan), editor. Libal, Kathryn, 1968- editor. (2019). Refugees and asylum seekers : interdisciplinary and comparative perspectives. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4408-5495-8. OCLC 1066056624.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration: A Report by The White House" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-21.

- ^ Bhandari, Aparajita, et al. "Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives on Digital Tools for U.S. Asylum Applicants Seeking Healthcare and Legal Information." Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, no. CSCW2, Nov. 2022, pp. 1-21. doi:10.1145/3359304.

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ Beirens, Hanne. Rebooting the Asylum System? The Role of Digital Tools in International Protection. Migration Policy Institute, Oct. 2022, www.migrationpolicy.org/research/rebooting-asylum-system-digital-tools

- ^ Beirens, Hanne. Rebooting the Asylum System? The Role of Digital Tools in International Protection. Migration Policy Institute, Oct. 2022, www.migrationpolicy.org/research/rebooting-asylum-system-digital-tools

- ^ Beirens, Hanne. Rebooting the Asylum System? The Role of Digital Tools in International Protection. Migration Policy Institute, Oct. 2022, www.migrationpolicy.org/research/rebooting-asylum-system-digital-tools

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ Bhandari, Aparajita, et al. "Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives on Digital Tools for U.S. Asylum Applicants Seeking Healthcare and Legal Information." Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, no. CSCW2, Nov. 2022, pp. 1-21. doi:10.1145/3359304.

- ^ Bhandari, Aparajita, et al. "Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives on Digital Tools for U.S. Asylum Applicants Seeking Healthcare and Legal Information." Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, no. CSCW2, Nov. 2022, pp. 1-21. doi:10.1145/3359304.

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ Beirens, Hanne. Rebooting the Asylum System? The Role of Digital Tools in International Protection. Migration Policy Institute, Oct. 2022, www.migrationpolicy.org/research/rebooting-asylum-system-digital-tools

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ "Primer: Defending the Rights of Refugees and Migrants in the Digital Age." Amnesty International, Jan. 2024.

- ^ Sanderson, Mike (2010-07-08). "Refugee Roulette: Disparities in Asylum Adjudication and Proposals for Reform by Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Andrew Ian Schoenholtz and Philip G. Schrag". The Modern Law Review. 73 (4): 679–682. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.2010.00814-1.x. ISSN 0026-7961.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (2008-08-23). "Vetted Judges More Likely to Reject Asylum Bids". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Office, U. S. Government Accountability. "U.S. Asylum System: Significant Variation Existed in Asylum Outcomes across Immigration Courts and Judges". www.gao.gov. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Schock, Katrin; Rosner, Rita; Knaevelsrud, Christine (September 2015). "Impact of asylum interviews on the mental health of traumatized asylum seekers". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 6 (1): 26286. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.26286. ISSN 2000-8198. PMC 4558273. PMID 26333540.

- ^ Belinda., Graham. Overgeneral memory in asylum seekers and refugees. OCLC 926274054.

- ^ Musalo, Karen; Meffert, Susan; Abdo, Akra (2010-01-01). "The Role of Mental Health Professionals in Political Asylum Processing". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 38 (4): 479–489. PMID 21156906.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (2021-03-23). "CBP Defends Conditions At Border Detention Centers Amid Upsurge In Migrants". NPR. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ Newman, Louise (2013-03-01). "Seeking Asylum—Trauma, Mental Health, and Human Rights: An Australian Perspective". Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 14 (2): 213–223. doi:10.1080/15299732.2013.724342. ISSN 1529-9732. PMID 23406225. S2CID 205868972.

- ^ Silove, Derrick (2000-08-02). "Policies of Deterrence and the Mental Health of Asylum Seekers". JAMA. 284 (5): 604–611. doi:10.1001/jama.284.5.604. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 10918707.

- ^ Ordóñez, J. Thomas (March 2008). "The state of confusion". Ethnography. 9 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1177/1466138108088948. ISSN 1466-1381. S2CID 143636389.

- ^ Leanza, Yvan; Miklavcic, Alessandra; Boivin, Isabelle; Rosenberg, Ellen (2013-07-16), "Working with Interpreters", Cultural Consultation, International and Cultural Psychology, New York, NY: Springer New York, pp. 89–114, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7615-3_5, ISBN 978-1-4614-7614-6, retrieved 2021-12-02

External links

[edit]- Obtaining Asylum in the United States (USCIS, Sept. 16, 2021)

- Asylum in the United States (American Immigration Council, June 11, 2020)

- Refugees and Asylees in the United States (Migration Policy Institute, May 13, 2021)

- Mexico to Allow U.S. ‘Remain in Mexico’ Asylum Policy to Resume (New York Times, Dec. 2, 2021)