Worship of heavenly bodies

The worship of heavenly bodies is the veneration of stars (individually or together as the night sky), the planets, or other astronomical objects as deities, or the association of deities with heavenly bodies. In anthropological literature these systems of practice may be referred to as astral cults.

The most notable instances of this are Sun gods and Moon gods in polytheistic systems worldwide. Also notable are the associations of the planets with deities in Sumerian religion, and hence in Babylonian and Greco-Roman religion, viz. Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Gods, goddesses, and demons may also be considered personifications of astronomical phenomena such as lunar eclipses, planetary alignments, and apparent interactions of planetary bodies with stars. The Sabians of Harran, a poorly understood pagan religion that existed in Harran during the early Islamic period (7th–10th century), were known for their astral cult.

The related term astrolatry usually implies polytheism. Some Abrahamic religions prohibit astrolatry as idolatrous. Pole star worship was also banned by imperial decree in Heian period Japan.

Etymology

[edit]Astrolatry has the suffix -λάτρης, itself related to λάτρις latris 'worshipper' or λατρεύειν latreuein 'to worship' from λάτρον latron 'payment'.

In historical cultures

[edit]Mesopotamia

[edit]Babylonian astronomy from early times associates stars with deities, but the identification of the heavens as the residence of an anthropomorphic pantheon, and later of monotheistic God and his retinue of angels, is a later development, gradually replacing the notion of the pantheon residing or convening on the summit of high mountains. Archibald Sayce (1913) argues for a parallelism of the "stellar theology" of Babylon and Egypt, both countries absorbing popular star-worship into the official pantheon of their respective state religions by identification of gods with stars or planets.[1]

The Chaldeans, who came to be seen as the prototypical astrologers and star-worshippers by the Greeks, migrated into Mesopotamia c. 940–860 BCE.[2] Astral religion does not appear to have been common in the Levant prior to the Iron Age, but becomes popular under Assyrian influence around the 7th-century BCE.[3] The Chaldeans gained ascendancy, ruling Babylonia from 608 to 557 BCE.[4] The Hebrew Bible was substantially composed during this period (roughly corresponding to the period of the Babylonian captivity).

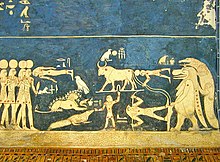

Egypt

[edit]

Astral cults were probably an early feature of religion in ancient Egypt.[5] Evidence suggests that the observation and veneration of celestial bodies played a significant role in Egyptian religious practices, even before the development of a dominant solar theology. The early Egyptians associated celestial phenomena with divine forces, seeing the stars and planets as embodiments of gods who influenced both the heavens and the earth.[6] Direct evidence for astral cults, seen alongside the dominant solar theology which arose before the Fifth Dynasty, is found in the Pyramid Texts.[7] These texts, among the oldest religious writings in the world, contain hymns and spells that not only emphasize the importance of the Sun God Ra but also refer to stars and constellations as powerful deities that guide and protect the deceased Pharaoh in the afterlife.[8]

The growth of Osiris devotion led to stars being called "followers" of Osiris.[9] They recognized five planets as "stars that know no rest", interpreted as gods who sailed across the sky in barques: Sebegu (perhaps a form of Set), Venus ("the one who crosses"), Mars ("Horus of the horizon"), Jupiter ("Horus who limits the two lands"), and Saturn ("Horus bull of the heavens.")[9]

One of the most significant celestial deities in ancient Egyptian religion was the goddess Sopdet, identified with the star Sirius.[10] Sopdet's rising coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile, a crucial event that sustained Egyptian agriculture. The goddess was venerated as a harbinger of the inundation, marking the beginning of a new agricultural cycle and symbolizing fertility and renewal. This connection between Sopdet and the Nile flood underscores the profound link between celestial phenomena and earthly prosperity in ancient Egyptian culture. She was known to the Greeks as Sothis. The significance of Sirius in Egyptian religion is further highlighted by its association with the goddess Isis during later periods, particularly in the Ptolemaic era, where Isis was often depicted as the star itself.[11]

Sopdet is the consort of Sah, the personified constellation of Orion near Sirius. Their child Venus[12] was the hawk god Sopdu,[13] "Lord of the East".[14] As the bringer of the New Year and the Nile flood, she was associated with Osiris from an early date[13] and by the Ptolemaic period Sah and Sopdet almost solely appeared in forms conflated with Osiris[15] and Isis.[16] Additionally, the alignment of architectural structures, such as pyramids and temples, with astronomical events reveals the deliberate integration of cosmological concepts into Egypt's built environment.[17] For example, the Great Pyramid of Giza is aligned with the cardinal points, and its descending passage is aligned with the star Thuban in the constellation Draco, which was the pole star at the time. This alignment likely served both symbolic and practical purposes, connecting the Pharaoh's eternal journey with the stars.[18]

Sabians

[edit]Among the various religious groups which in the 9th and 10th centuries CE came to be identified with the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran (sometimes also spelled 'Sabaeans' or 'Sabeans', but not to be confused with the Sabaeans of South Arabia),[19] at least two groups appear to have engaged in some kind of star worship.

By far the most famous of these two are the Sabians of Harran, adherents of a Hellenized Semitic pagan religion that had managed to survive during the early Islamic period in the Upper Mesopotamian city of Harran.[20] They were described by Syriac Christian heresiographers as star worshippers.[21] Most of the scholars and courtiers working for the Abbasid and Buyid dynasties in Baghdad during the ninth–eleventh centuries who were known as 'Sabians' were either members of this Harranian religion or descendants of such members, most notably the Harranian astronomers and mathematicians Thabit ibn Qurra (died 901) and al-Battani (died 929).[22] There has been some speculation on whether these Sabian families in Baghdad, on whom most of our information about the Harranian Sabians indirectly depends, may have practiced a different, more philosophically inspired variant of the original Harranian religion.[23] However, apart from the fact that it contains traces of Babylonian and Hellenistic religion, and that an important place was taken by planets (to whom ritual sacrifices were made), little is known about Harranian Sabianism.[24] They have been variously described by scholars as (neo)-Platonists, Hermeticists, or Gnostics, but there is no firm evidence for any of these identifications.[25][a]

Apart from the Sabians of Harran, there were also various religious groups living in the Mesopotamian Marshes who were called the 'Sabians of the Marshes' (Arabic: Ṣābiʾat al-baṭāʾiḥ).[26] Though this name has often been understood as a reference to the Mandaeans, there was in fact at least one other religious group living in the marshlands of Southern Iraq.[27] This group still held on to a pagan belief related to Babylonian religion, in which Mesopotamian gods had already been venerated in the form of planets and stars since antiquity.[28] According to Ibn al-Nadim, our only source for these star-worshipping 'Sabians of the Marshes', they "follow the doctrines of the ancient Aramaeans [ʿalā maḏāhib an-Nabaṭ al-qadīm] and venerate the stars".[29] However, there is also a large corpus of texts by Ibn Wahshiyya (died c. 930), most famously his Nabataean Agriculture, which describes at length the customs and beliefs — many of them going back to Mespotamian models — of Iraqi Sabians living in the Sawād.[30]

China

[edit]

Heaven worship is a Chinese religious belief that predates Taoism and Confucianism, but was later incorporated into both. Shangdi is the supreme unknowable god of Chinese folk religion. Over time, namely following the conquests of the Zhou dynasty who worshipped Tian (天 lit. "sky"), Shangdi became synonymous with Tian, or Heaven. During the Zhou dynasty, Tian not only became synonymous with the physical sky but also embodied the divine will, representing the moral order of the universe. This evolution marked a shift from the earlier concept of Shangdi to a more abstract and universal principle that guided both natural and human affairs.[31] In the Han dynasty the worship of Heaven would be highly ritualistic and require that the emperor hold official sacrifices and worship at an altar of Heaven, the most famous of which is the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.[32][33]

Heaven worship is closely linked with ancestor veneration and polytheism, as the ancestors and the gods are seen as a medium between Heaven and man. The Emperor of China, also known as the "Son of Heaven", derived the Mandate of Heaven, and thus his legitimacy as ruler, from his supposed ability to commune with Heaven on behalf of his nation.[34][35] This mandate was reinforced through celestial observations and rituals, as astrological phenomena were interpreted as omens reflecting the favor or disfavor of Heaven. The Emperor’s role was to perform the necessary rites to maintain harmony between Heaven and Earth, ensuring the prosperity of his reign.[36]

Star worship was widespread in Asia, especially in Mongolia[37] and northern China, and also spread to Korea.[38] According to Edward Schafer, star worship was already established during the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), with the Nine Imperial Gods becoming star lords.[39] The Big Dipper (Beidou) and the North Star (Polaris) were particularly significant in Chinese star worship. The Big Dipper was associated with cosmic order and governance, while the North Star was considered the throne of the celestial emperor. These stars played a crucial role in state rituals, where the Emperor’s ability to align these celestial forces with earthly governance was seen as essential to his legitimacy.[31] This star worship, along with indigenous shamanism and medical practice, formed one of the original bases of Taoism.[40] The Heavenly Sovereign was identified with the Big Dipper and the North Star.[41] Worship of Heaven in the southern suburb of the capital was initiated in 31 BCE and firmly established in the first century CE (Western Han).[42]

The Sanxing (Chinese: 三星; lit. 'Three Stars') are the gods of the three stars or constellations considered essential in Chinese astrology and mythology: Jupiter, Ursa Major, and Sirius. Fu, Lu, and Shou (traditional Chinese: 福祿壽; simplified Chinese: 福禄寿; pinyin: Fú Lù Shòu; Cantonese Yale: Fūk Luhk Sauh), or Cai, Zi and Shou (財子壽) are also the embodiments of Fortune (Fu), presiding over planet Jupiter, Prosperity (Lu), presiding over Ursa Major, and Longevity (Shou), presiding over Sirius.[43]

During the Tang dynasty, Chinese Buddhism adopted Taoist Big Dipper worship, borrowing various texts and rituals which were then modified to conform with Buddhist practices and doctrines. The integration of Big Dipper worship into Buddhist practices highlights the adaptability of star worship in China, where it was syncretized with various religious traditions over time.[31] The cult of the Big Dipper was eventually absorbed into the cults of various Buddhist divinities, Myōken being one of these.[44]

Japan

[edit]Star worship was also practiced in Japan.[45][46][47] Japanese star worship is largely based on Chinese cosmology.[48] According to Bernard Faure, "the cosmotheistic nature of esoteric Buddhism provided an easy bridge for cultural translation between Indian and Chinese cosmologies, on the one hand, and between Indian astrology and local Japanese folk beliefs about the stars, on the other".[48]

Originally an 11th-century Buddhist temple dedicated to Myōken, converted into a Shinto shrine during the Meiji period.

The cult of Myōken is thought to have been brought into Japan during the 7th century by immigrants (toraijin) from Goguryeo and Baekje. During the reign of Emperor Tenji (661–672), the toraijin were resettled in the easternmost parts of the country; as a result, Myōken worship spread throughout the eastern provinces.[49]

By the Heian period, pole star worship had become widespread enough that imperial decrees banned it for the reason that it involved "mingling of men and women", and thus caused ritual impurity. Pole star worship was also forbidden among the inhabitants of the capital and nearby areas when the imperial princess (Saiō) made her way to Ise to begin her service at the shrines. Nevertheless, the cult of the pole star left its mark on imperial rituals such as the emperor's enthronement and the worship of the imperial clan deity at Ise Shrine.[50] Worship of the pole star was also practiced in Onmyōdō, where it was deified as Chintaku Reifujin (鎮宅霊符神).[51]

Myōken worship was particularly prevalent among clans based in eastern Japan (the modern Kantō and Tōhoku regions), with the Kanmu Taira clan (Kanmu Heishi) and their offshoots such as the Chiba and the Sōma clans being among the deity's notable devotees. One legend claims that Taira no Masakado was a devotee of Myōken, who aided him in his military exploits. When Masakado grew proud and arrogant, the deity withdrew his favor and instead aided Masakado's uncle Yoshifumi, the ancestor of the Chiba clan.[52] Owing to his status as the Chiba clan's ujigami (guardian deity), temples and shrines dedicated to Myōken are particularly numerous in former Chiba territories.[53] Myōken worship is also prevalent in many Nichiren-shū Buddhist temples due to the clan's connections with the school's Nakayama lineage.[54]

Indigenous America

[edit]Celestial objects hold a significant place within Indigenous American cultures.[55][56][failed verification] From the Lakota in North America to the Inca in South America, the celestial realm was integrated into daily life. Stars served as navigation aids, temporal markers, and spiritual conduits, illustrating their practical and sacred importance.[55][57]

Heavenly bodies held spiritual wisdom. The Pleiades, revered in various cultures, symbolized diverse concepts such as agricultural cycles and ancestral spirits.[58] In North America, star worship was practiced by the Lakota people[59][60][61] and the Wichita people.[62] The Inca civilization engaged in star worship,[63] and associated constellations with deities and forces, while the Milky Way represented a bridge between earthly and divine realms.[57]

Indigenous American cultures encapsulate a holistic worldview that acknowledges the interplay of humanity, nature, and the cosmos. Oral traditions transmitted cosmic stories, infusing mythologies, songs, and ceremonies with cosmic significance.[58] These narratives emphasized the belief that the celestial realm offered insights into origins and purpose.[55]

In contemporary religions

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Astrolatry. (Discuss) (October 2024) |

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2024) |

Judaism

[edit]The Hebrew Bible contains repeated reference to astrolatry. Deuteronomy 4:19, 17:3 contains a stern warning against worshipping the Sun, Moon, stars or any of the heavenly host. Relapse into worshipping the host of heaven, i.e. the stars, is said to have been the cause of the fall of the kingdom of Judah in II Kings 17:16. King Josiah in 621 BCE is recorded as having abolished all kinds of idolatry in Judah, but astrolatry was continued in private (Zeph. 1:5; Jer. 8:2, 19:13). Ezekiel (8:16) describes sun-worship practised in the court of the temple of Jerusalem, and Jeremiah (44:17) says that even after the destruction of the temple, women in particular insisted on continuing their worship of the "Queen of Heaven".[64]

Christianity

[edit]

Crucifixion darkness is an episode described in three of the canonical gospels in which the sky becomes dark during the day, during the crucifixion of Jesus as a sign of his divinity.[65]

Augustine of Hippo criticized sun- and star-worship in De Vera Religione (37.68) and De civitate Dei (5.1–8). Pope Leo the Great also denounced astrolatry and the cult of Sol Invictus, which he contrasted with the Christian nativity.[citation needed]

Jesus Christ holds a significant place in the context of Christian astrology. His birth is associated with an astronomical event, symbolized by the star of the king of the Jews. This event played a role in heralding his arrival and was considered a sign of his divine nature. The belief in Jesus as the Messiah, the anointed one, drew upon astrological concepts and symbolism. The incorporation of cosmological elements into the narrative of Jesus' life and divinity contributed to the development and interpretation of Christian theology.[66]

Islam

[edit]

Worship of heavenly bodies is in Islamic tradition strongly associated with Sabians who allegedly stated that God created the planets as the rulers of this world and thus deserve worship.[67] While the planetary worship was linked to devils (shayāṭīn),[68] abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi reported that the planets are considered angelic spirits at the service of God.[69] He refutes the notion that astrology is based on the interference of demons or "guesswork" and established the study of the planets as a form of natural sciences.[70] By building a naturalistic connection between the planets and their earthly influence, abu Marsha saved astrology from accusations of devil-worship.[71] Such ideas were universally shared, for example, Mashallah ibn Athari denied any physical or magical influence on the world.[72]

Abu Ma‘shar further describes the planets as sentient bodies, endowed with spirit (rūḥ) rather than mechanical entities.[73] However, they would remain in complete obedience to God and act only with God's permission.[73] Astrology was usually considered through the lens of Hellenistic philosophy such as Neo-Platonism and Aristotelianism. As the spiritual powers allegedly emanating from the planets are explained to derive from the Anima mundi, the writings clearly distanced them from demonic entities such as jinn and devils.[74]

At a later stage, the planetary spirits have been identified with the angels and demons. The idea of seven demon-kings developed under influence of Hellenistic astrological sources.[75] In the Kitāb al-Bulhān, higher spirits (rūḥāiya ulia) are depicted as angels and lower spirits (rūḥāiya sufula) as demons.[76] However, invocation of such entities would work only by permission of God. Permission granted by the angels is supposed to be required in order to receive command over the demon or jinn. A common structure around the spiritual entities and the days of the week goes as follows:

| Planet | Day | Angel that monitors the associated ‘Afārīt

(Arabic; Hebrew equivalent) |

‘Afārīt | Type of madness (جُنُون, junūn) and parts of the body attacked | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Known other names | |||||

| Sun | Sunday | Ruqya'il (روقيائيل); Raphael (רפאל) | Al-Mudhdhahab/ Al-Mudhhib/ Al-Mudhhab (المذهب; The Golden One) | Abu 'Abdallah Sa'id | the name "Al-Mudh·dhahab" refers to the jinn's skin tone. | |

| Moon | Monday | Jibril (جبريل); Gabriel (גבריאל) | Al-Abyaḍ (الابيض; The White One) | Murrah al-Abyad Abu al-Harith; Abu an-Nur | Whole body | the name "Al-Abyaḍ" refers to the jinn's skin tone, however he is portrayed as a "dark black, charcoal" figure. The possible connection of this name is with another name "Abū an-Nūr" ("Father of Light"); his names are the same as whose applied to Iblīs. |

| Mars | Tuesday | Samsama'il (سمسمائيل); Samael (סמאל) | Al-Aḥmar (الاحمر; The Red One) | Abu Mihriz; Abu Ya'qub | Head, uterus | the name "Al-Aḥmar" refers to the jinn's skin tone. |

| Mercury | Wednesday | Mikail (ميكائيل); Michael (מיכאל) | Būrqān/ Borqaan (بورقان; Two Thunders) | Abu al-'Adja'yb; Al-Aswad | Back | |

| Jupiter | Thursday | Sarfya'il (صرفيائيل); Zadkiel (צדקיאל) | Shamhuresh (شمهورش) | Abu al-Walid; At-Tayyar | Belly | |

| Venus | Friday | 'Anya'il (عنيائيل); Anael (ענאל) | Zawba'ah (زوبعة; Cyclone, Whirlwind) | Abu Hassan | It is said the "whirlwind" (zawba'ah), to be caused by an evil jinn which travels inside it. | |

| Saturn | Saturday | Kasfa'il (كسفيائيل); Cassiel (קפציאל) | Maymun (ميمون; Prosperous) | Abu Nuh | Feet | His name means "monkey"[77] |

See also

[edit]- Archeoastronomy

- Astraea

- Astraeus

- Astronomy and religion

- Astrological age

- Astrotheology

- Babylonian astrology

- Behenian fixed star

- Body of light

- Ceremonial magic

- Decan

- Eosphorus

- Hellenistic astrology

- History of astrology

- History of astronomy

- Lunar station

- Magic and religion

- Natural theology

- Nature worship

- Pantheon

- Planets in astrology

- Pleiades in folklore and literature

- Religious cosmology

- Renaissance magic

- Royal stars

- Seven heavens

- Sidereal compass rose

- Stars in astrology

- Sky father

- Star people

- Stellar deities

- Venusian deities

Notes

[edit]- ^ On the Sabians of Harran, see further Dozy & de Goeje (1884); Margoliouth (1913); Tardieu (1986); Tardieu (1987); Peters (1990); Green (1992); Fahd (1960–2007); Strohmaier (1996); Genequand (1999); Elukin (2002); Stroumsa (2004); De Smet (2010).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Sayce (1913), pp. 237ff.

- ^ Oppenheim & Reiner (1977).

- ^ Cooley (2011), p. 287.

- ^ Beaulieu (2018), pp. 4, 12, 178.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 12.

- ^ Allen (1997); Richter (2004).

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 90.

- ^ Allen (2005); Assmann (2001).

- ^ a b Wilkinson (2003), p. 91.

- ^ Redford (2001).

- ^ Richter (2004); Krauss (1997).

- ^ Hill (2016).

- ^ a b Wilkinson (2003), p. 167.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 211.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 127.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 168.

- ^ Ritner (1993).

- ^ Spence (2000); Belmonte (2001).

- ^ On the Sabians generally, see De Blois (1960–2007); De Blois (2004); Fahd (1960–2007); Van Bladel (2009).

- ^ De Blois (1960–2007).

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 68; cf. p. 70.

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 65. A genealogical table of Thabit ibn Qurra's family is given by De Blois (1960–2007). On some of his descendants, see Roberts (2017).

- ^ Hjärpe (1972) (as cited by Van Bladel (2009), pp. 68–69).

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 70.

- ^ Van Bladel (2017), pp. 14, 71. On the Mesopotamian Marshes in the early Islamic period, see pp. 60–69.

- ^ Van Bladel (2017), p. 71. According to Van Bladel there were two other groups, the third one being Elchasaites, whom other scholars see as Mandaeans.

- ^ Van Bladel (2017), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Translation by Van Bladel (2017), p. 71.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila (2006), pp. 46–52.

- ^ a b c Needham (1959).

- ^ Lü & Gong (2014), p. 71.

- ^ Yao & Zhao (2010), p. 155.

- ^ Fung (2008), p. 163.

- ^ Lü & Gong (2014), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Needham (1959); Schafer (1977).

- ^ Heissig (1980), pp. 82–4.

- ^ Yu & Lancaster (1989), p. 58.

- ^ Schafer (1977), p. 221.

- ^ Gillman (2010), p. 108.

- ^ Master of Silent Whistle Studio (2020), p. 211, n.16.

- ^ Liu (1990).

- ^ (in Chinese) 福禄寿星 Archived 2006-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. British Taoist Association.

- ^ Orzech, Sørensen & Payne (2011), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Bocking (2006).

- ^ Goto (2020).

- ^ Rambelli & Teeuwen (2003).

- ^ a b Faure (2015), p. 52.

- ^ "妙見菩薩と妙見信仰". 梅松山円泉寺. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ Rambelli & Teeuwen (2003), pp. 35–36, 164–167.

- ^ Friday (2017), p. 340.

- ^ "千葉神社". 本地垂迹資料便覧 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ "千葉氏と北辰(妙見)信仰". Chiba City Official Website (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ "妙見菩薩「開運大野妙見大菩薩」". 日蓮宗 法華道場 光胤山 本光寺 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ a b c Bucko (1998).

- ^ Valencius (2013).

- ^ a b Jones (2015).

- ^ a b Spence (1990).

- ^ Means (2016).

- ^ Goodman (2017).

- ^ Lockett (2018).

- ^ La Vere (1998), p. 7.

- ^ Cobo (1990), pp. 25–31.

- ^ Seligsohn (1906).

- ^ Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44.

- ^ Rosenberg (1972).

- ^ Almutlaq, Khalid M. (2023). "The Sabian doctrine in the Interpretations of the interpreters of the Qur'an". Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences. 10 (3S): 32–40.

- ^ Mazuz, Haggai (2012). "The Identity of the Sabians: Some Insights". In Schwartz, D.; Jospe, R. (eds.). Jewish Philosophy: Perspectives and Retrospectives. p. 251.[full citation needed]

- ^ Pingree (2002).

- ^ Saif (2015), p. 14.

- ^ Saif (2015), p. 27.

- ^ Saif (2015), p. 16.

- ^ a b Saif (2015), p. 19.

- ^ Saif (2015), p. 40.

- ^ Savage-Smith (2021), p. 25.

- ^ Mommersteeg (1988).

- ^ Carboni (2013), pp. 27–28.

Works cited

[edit]- Allen, James P. (1997). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press.

- Allen, James P. (2005). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Assmann, Jan (2001). The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Belmonte, Juan Antonio (2001). "On the Orientation of Old Kingdom Egyptian Pyramids". Archaeoastronomy. 26: S1–S20. Bibcode:2001JHAS...32....1B.

- Bocking, B. (2006). Dolce, Lucia (ed.). "The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice". Special Double Issue of Culture and Cosmos: A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy. 10 (1–2). Bristol: Culture and Cosmos. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000421. ISSN 1368-6534.

- Bogdan, Henrik (2008). Western Esotericism and Rituals of Initiation. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7070-1.

- Bucko, Raymond A. (1998). The Lakota Ritual of the Sweat Lodge: History and Contemporary Practice. University of Nebraska Press.

- Carboni, Stefano (2013). "The Book of Surprises (Kitab al-Buhlan) of the Bodleian Library". The La Trobe Journal. 91.

- Churton, Tobias (2005). Gnostic Philosophy: From Ancient Persia to Modern Times. Inner Traditions/Bear. ISBN 978-1-59477-767-7.

- Cobo, Father Berrnabe (1990). Hamilton, Roland (ed.). Inca Religion and Customs. Translated by Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292738546.

- Cooley, J. L. (2011). "Astral Religion in Ugarit and Ancient Israel". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 70 (2): 281–287. doi:10.1086/661037. S2CID 164128277.

- Crowley, Aleister (1969). The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-80903-591-X.

- Crowley, Aleister (1976). The Book of the Law: Liber AL vel Legis. York Beach, Maine: Weiser Books. ISBN 978-0-87728-334-8.

- Crowley, Aleister (1991). The Equinox of the Gods. United States: New Falcon Publications. ISBN 1-56184-028-9.

- Crowley, Aleister (1997). Magick: Liber ABA, Book 4, Parts I-IV (2nd rev. ed.). Boston: Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-919-0.

- De Blois, François (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0952.

- De Blois, François (2004). "Sabians". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00362.

- De Smet, Daniel (2010). "Le Platon arabe et les Sabéens de Ḥarrān. La 'voie diffuse' de la transmission du platonisme en terre d'Islam". Res Antiquae. 7: 73–86. ISBN 978-2-87457-034-6.

- Djurdjevic, Gordan (2012). "The Great Beast as a Tantric Hero". In Bogdan, Henrik; Starr, Martin P. (eds.). Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism. Oxford University Press. pp. 107–140. ISBN 978-0-19-986309-9.

- Dozy, Reinhart Pieter Anne; de Goeje, Michael Jean (1884). "Mémoire posthume de M. Dozy: contenant de Nouveaux documents pour l'étude de la religion des Harraniens, achevé par M. J. de Goeje". Travaux de la 6e session du Congrès international des Orientalistes à Leide. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill. pp. 283–366. OCLC 935749094.

- DuQuette, Lon Milo (2003). The Magick of Aleister Crowley: A Handbook of Rituals of Thelema. San Francisco and Newburyport: Weiser. ISBN 1-57863-299-4.

- Elukin, Jonathan (2002). "Maimonides and the Rise and Fall of the Sabians: Explaining Mosaic Laws and the Limits of Scholarship". Journal of the History of Ideas. 63 (4): 619–637. doi:10.2307/3654163. JSTOR 3654163.

- Fahd, Toufic (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾa". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0953.

- Faure, B. (2015). The Fluid Pantheon: Gods of Medieval Japan. Vol. 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824857028.

- Friday, Karl F., ed. (2017). Routledge Handbook of Premodern Japanese History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351692021.

- Fung, Yiu-ming (2008). "Problematizing Contemporary Confucianism in East Asia". In Richey, Jeffrey (ed.). Teaching Confucianism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198042563.

- Genequand, Charles (1999). "Idolâtrie, astrolâtrie, et sabéisme". Studia Islamica. 89 (89): 109–128. doi:10.2307/1596088. JSTOR 1596088.

- Gillman, D. (2010). The Idea of Cultural Heritage. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521192552.

- Goodman, R. (2017). Lakota Star Knowledge: Studies in Lakota Stellar Theology. SGU Publishing. ISBN 978-0998950501.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971756-9.

- Goto, Akira (2020). Cultural Astronomy of the Japanese Archipelago: Exploring the Japanese Skyscape. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0367407988.

- Green, Tamara M. (1992). The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 114. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09513-7.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15010-2.

- Hedenborg-White, Manon (2020). "Double Toil and Gender Trouble: Performativity and Femininity in the Cauldron of Esotericism Research". In Asprem, Egil; Strube, Julian (eds.). New Approaches to the Study of Esotericism. Netherlands: Brill. pp. 182–200. ISBN 978-90-04-44645-8.

- Heissig, Walther (1980). The Religions of Mongolia. Translated by Geoffrey Samuel. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520038578.

- Hill, J. (2016). "Sopdet". Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Hjärpe, Jan (1972). Analyse critique des traditions arabes sur les Sabéens harraniens (PhD diss.). University of Uppsala.

- Jones, David M. (2015). The Inca World: Ancient People & Places. Thames & Hudson.

- Kaczynski, Richard (2012). Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley (rev. & exp. ed.). North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-58394-576-6.

- Krauss, Rolf (1997). "Sothis and the Satet Temple on Elephantine: The Beginning of the Egyptian Calendar". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

- La Vere, D. (1998). Life Among the Texas Indians: The WPA Narratives. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-1603445528.

- Lachman, Gary (2014). Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, and the Wickedest Man in the World. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-14653-2.

- Liu, Kwang-ching (1990). "Socioethics as Orthodoxy". In Liu, Kwang-ching (ed.). Orthodoxy In Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 53–100. ISBN 978-0-520-30187-0.

- Lockett, Chynna (October 3, 2018). "Lakota Star Knowledge-Milky Way Spirit Path". SDPB Radio. South Dallas Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Lü, Daji; Gong, Xuezeng (2014). Marxism and Religion. Religious Studies in Contemporary China. Brill. ISBN 978-9047428022.

- Margoliouth, D.S. (1913). "Harranians". In Hastings, James; Selbie, John A. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. VI. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 519–520. OCLC 4993011.

- Master of Silent Whistle Studio (2020). Further Adventures on the Journey to the West. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295747736.

- Means, Binesikwe (September 12, 2016). "For Lakota, Traditional Astronomy is Key to Their Culture's Past and Future". Global Press Journal. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Mommersteeg, Geert (1988). "'He Has Smitten Her to the Heart with Love': The Fabrication of an Islamic Love-Amulet in West Africa". Anthropos. 83 (4/6): 501–510. JSTOR 40463380.

- Needham, Joseph (1959). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:1959scc3.book.....N.

- Oppenheim, A. L.; Reiner, E. (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226631875.

- Orzech, Charles; Sørensen, Henrik; Payne, Richard, eds. (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill. ISBN 978-9004184916.

- Pasi, Marco (2021). "Aleister Crowley and Islam". In Sedgwick, Mark; Piraino, Francesco (eds.). Esoteric Transfers and Constructions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Germany: Springer International Publishing. pp. 151–194. ISBN 978-3-030-61788-2.

- Peters, Francis E. (1990). "Hermes and Harran: The Roots of Arabic-Islamic Occultism". In Mazzaoui, M.; Moreen, V.B. (eds.). Intellectual Studies on Islam: Essays Written in Honor of Martin B. Dickson. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. pp. 185–215. ISBN 9780874803426.

- Pingree, David (2002). "The Ṣābians of Ḥarrān and the Classical Tradition". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 9 (1): 8–35. doi:10.1007/BF02901729. JSTOR 30224282. S2CID 170507750.

- Rambelli, Fabio; Teeuwen, Mark, eds. (2003). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0415297479.

- Redford, Donald B. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- Richter, Barbara A. (2004). The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary. Berkeley: University of California.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1993). The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 54.

- Roberts, Alexandre M. (2017). "Being a Sabian at Court in Tenth-Century Baghdad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 137 (2): 253–277. doi:10.17613/M6GB8Z.

- Rosenberg, R. A. (1972). "The 'Star of the Messiah' Reconsidered". Biblica. 53 (1): 105–109. JSTOR 42609680.

- Saif, Liana (2015). The Arabic influences on early modern occult philosophy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie, ed. (2021). Magic and Divination in Early Islam. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-92101-5.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1913). The Religion of Ancient Egypt. Adamant Media Corporation.

- Schafer, E. H. (1977). Pacing the Void : Tʻang Approaches to the Stars. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520033443.

- Seligsohn, M. (1906). "Star-worship". Jewish Encyclopedia – via jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Shoemaker, David (2024). "The Worship of Nuit". The Way of the Will: Thelema in Action. Red Wheel/Weiser. pp. 89–98. ISBN 978-1-57863-826-0.

- Spence, Kate (16 November 2000). "Ancient Egyptian chronology and the astronomical orientation of pyramids". Nature. 408(6810) (6810): 320–4. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..320S. doi:10.1038/35042510. PMID 11099032.

- Spence, Lewis (1990). The Myths of Mexico and Peru. Dover Publications.

- Strohmaier, Gotthard [in German] (1996). "Die ḥarrānischen Sabier bei Ibn an-Nadīm und al-Bīrūnī". Ibn an-Nadīm und die mittelalterliche arabische Literatur: Beiträge zum 1. Johann Wilhelm Fück-Kolloquium (Halle 1987). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 51–56. ISBN 9783447037457. OCLC 643711267.

- Reprinted in Strohmaier, Gotthard (2003). Hellas im Islam: Interdisziplinäre Studien zur Ikonographie, Wissenschaft und Religionsgeschichte. Diskurse der Arabistik. Vol. 6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-3-447-04637-4.

- Stroumsa, Sarah (2004). "Sabéens de Ḥarrān et Sabéens de Maïmonide". In Lévy, Tony; Rashed, Roshdi (eds.). Maïmonide: Philosophe et savant (1138–1204). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 335–352. ISBN 9789042914582.

- Tardieu, Michel (1986). "Ṣābiens coraniques et 'Ṣābiens' de Ḥarrān". Journal Asiatique. 274 (1–2): 1–44. doi:10.2143/JA.274.1.2011565.

- Tardieu, Michel (1987). "Les calendriers en usage à Ḥarrān d'après les sources arabes et le commentaire de Simplicius à la Physique d'Aristote". In Hadot, Ilsetraut (ed.). Simplicius. Sa vie, son œuvre, sa survie. Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 40–57. doi:10.1515/9783110862041.41. ISBN 9783110109245.

- Valencius, Conevery (2013). The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes. University of Chicago Press.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). "Hermes and the Ṣābians of Ḥarrān". The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–118. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195376135.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2017). From Sasanian Mandaeans to Ṣābians of the Marshes. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004339460. ISBN 978-90-04-33943-9.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). "Sothis". The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 167–168. ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- Yao, Xinzhong; Zhao, Yanxia (2010). Chinese Religion: A Contextual Approach. London: A&C Black. ISBN 9781847064752.

- Yu, Chai-Shin; Lancaster, Lewis R., eds. (1989). Introduction of Buddhism to Korea: New Cultural Patterns. South Korea: Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0895818881.

Further reading

[edit]- Aakhus, P. (2008). "Astral Magic in the Renaissance: Gems, Poetry, and Patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici". Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft. 3 (2): 185–206. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0103. S2CID 161829239.

- Albertz, R.; Schmitt, R (2012). Family and Household Religion in Ancient Israel and the Levant. United States: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-1575062327.

- Al-Ghazali, Muhammad (2007). Ihya' Ulum al-Din [Revival of the Religious Sciences]. Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah.

- Ananthaswamy, Anil (14 August 2013). "World's oldest temple built to worship the dog star". New Scientist. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Bender, Herman E. (2017). "The Star Beings and stones: Petroforms and the reflection of Native American cosmology, myth and stellar traditions". Journal of Lithic Studies. 4 (4): 77–116. doi:10.2218/jls.v4i4.1918. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Brown, R. H. (2002). Stellar Theology and Masonic Astronomy. Book Tree. ISBN 978-1-58509-203-1.

- Campion, Nicholas (2012). Astrology and Cosmology in the World's Religions. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-0842-2.

- Hill, J. H. (2009) [1895]. Astral Worship. United States: Arc Manor. ISBN 978-1604507119.

- Kim, S. (2019). Shinra Myōjin and Buddhist Networks of the East Asian "Mediterranean". University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824877996.

- Kristensen, W. Brede (1960). "The Worship of the Sky and of Celestial Bodies". The Meaning of Religion. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 40–87. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-6580-0_3. ISBN 978-94-017-6451-3.

- Makemson, Maud W. (1954). "Astronomy in Primitive Religion". The Journal of Bible and Religion. 22 (3): 163–171. JSTOR 1455974.

- McCluskey, S. C. (2000). Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521778527.

- Mortimer, J. R. (1896). "Ancient British Star-worship indicated by the Grouping of Barrows". Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological and Polytechnic Society. 13 (2): 201–209. Bibcode:1896PYGS...13..201M. doi:10.1144/pygs.13.2.201. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Pasi, M. (2011). "Varieties of Magical Experience: Aleister Crowley's Views on Occult Practice". Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft. 6 (2): 123–162. doi:10.1353/mrw.2011.0018. S2CID 143532692.

- Pedersen, Hillary Eve (2010). The Five Great Space Repository Bodhisattvas: Lineage, Protection and Celestial Authority in Ninth-Century Japan (PDF) (PhD dissertation). University of Kansas. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Reiner, Erica (1995). "Astral Magic in Babylonia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 85 (4): i-150. doi:10.2307/1006642. JSTOR 1006642.

- Rohrbacher, Peter (2019). "Encrypted Astronomy: Astral Mythologies and Ancient Mexican Studies in Austria, 1910–1945". Revista de Antropologia. 62 (1). Universidade de São Paulo: 140–161. doi:10.11606/2179-0892.ra.2019.157035. S2CID 151040522.

- Rumor, Maddalena (2020). "Babylonian Astro-Medicine, Quadruplicities and Pliny the Elder". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 111 (1): 47–76. doi:10.1515/za-2021-0007. S2CID 235779490.

- Schaafsma, P. (2015). "The Darts of Dawn: The Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli Venus Complex in the Iconography of Mesoamerica and the American Southwest". Journal of the Southwest. 57 (1): 1–102. doi:10.1353/jsw.2015.0000. S2CID 109601941. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Selin, Helaine (2014). Astronomy Across Cultures. Springer My Copy UK. ISBN 978-9401141802.

- Serra, Nick (2014). "Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism". Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft. 9 (1): 107–113. doi:10.1353/mrw.2014.0012. S2CID 162315360.

- Spence, Lewis (1917). "Chapter VIII - Babylonian Star-worship". Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria. Retrieved 2021-12-04 – via wisdomlib.org.

- Springett, B. H. (2016). Secret Sects of Syria. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138981546.

- Tanzella-Nitti, Giuseppe (2002). "Sky". Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science. doi:10.17421/2037-2329-2002-GT-7. ISSN 2037-2329.

- Ten Grotenhuis, E. (1998). Japanese Mandalas: Representations of Sacred Geography. University of Hawaii Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0824863111. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Thompson, Cath (2017). A Handbook of Stellar Magick. West Yorkshire: Hadean Press. ISBN 978-1907881718.

- VanPool, Christine S.; VanPool, Todd L.; Phillips, David A. (Jr.), eds. (2006). Religion in the Prehispanic Southwest. AltaMira Press.

- Wheeler, Brannon M.; Walker, Joel Thomas; Noegel, Scott B., eds. (2003). Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271022574.

External links

[edit]- The Development, Heyday, and Demise of Panbabylonism by Gary D. Thompson

- Native American Star Lore Dakota and Lakota

- The Star Mandala Archived 2021-12-04 at the Wayback Machine at Kyoto National Museum

- Star Worship in Japan, 28 Constellations (Lunar Mansions, Moon Stations), Pole Star, Big Dipper, Planets, Nine Luminaries